ABSTRACT

The diversity of tourists in terms of age poses challenges for the tourism industry; tourist experience may be hindered by stereotypes and prejudices directed at older people. This study introduces the concept of ageism in tourism and empirically tests it by relying on intergroup contact theory. Specifically, the antecedents of ageism in tourism are explored by investigating the impact of contact quality on ageism and addressing the mediating roles of metastereotypes and aging anxiety, and the moderating role of gender. This study is based on a survey using a self-administered questionnaire with 530 responses. Data were collected from young people aged 18–35. Based on SEM modeling, our results confirm the direct link between contact quality and ageism in tourism and find evidence for the mediating role of metastereotypes. The moderating role of gender is identified in the relationship between aging anxiety and ageism suggesting that men and women have different coping strategies when facing aging anxiety. To reduce ageism in the tourism industry, intervention efforts are needed. Based on our findings, we propose a combination of educational and intergenerational contact interventions.

1. Introduction

There has been an expansion in tourism among older people in recent years due to the increasing proportion of older adults living a longer and healthier life. In 2017, 62.7% of the EU-28 population aged 55–64 and 47.4% of those aged 65 years or more participated in tourism (Eurostat, Citation2019). These trends imply that tourism and travel-related services will have to cope with challenges resulting from the diversity of customers in terms of age differences. Ideally, interactions between members of different generations enrich the holistic tourist experience encountered during the pre-visit, on-site and the post-visit stages of a trip (Godovykh & Tasci, Citation2020) and contribute to the creation of wellbeing-enhancing experiences for tourists (Smith & Diekmann, Citation2017).

Customer age differences however often negatively influence customer-to-customer interactions as people tend to be more at ease with others who are perceived as being similar with them (Brocato et al., Citation2012). Especially, the interaction between younger and older adults may be perceived negatively by young people who often prefer to spend their time with their age group or even be separated physically from older adults (Nicholls & Mohsen, Citation2015). This is highlighted by the following quotation describing the experience of a young couple (Grove & Fisk, Citation1997, p. 73): ‘Busch Gardens had like way too many silverheads (older people), they get in your way’. This quotation is an example of age-related stereotypes and prejudices which are the manifestations of ageism (Ayalon et al., Citation2019) and are increasingly considered as a threat to the quality of life of older people.

Ageism prevails in different areas of life including the workplace, media, leisure and travel. Independently from the area of life affected, ageism is proven to hinder active ageing and negatively impacts older people’s wellbeing, especially that of older consumers who are far from the idealized image of successful ageing (Stončikaitė, Citation2021). While ageism has been researched in various contexts, none of the existing studies examined its implications for customer-to-customer interactions in tourism. Our study fills this research gap by introducing and operationalizing the concept of ageism in tourism focusing on young people’s attitudes. The underlying theory is the intergroup contact theory proposed by Allport (Citation1954) and considered later as one of most influential theory of prejudice reduction. We investigate the impact of prior contact with older adults on ageism, the roles of metastereotypes and aging anxiety as antecedents to ageism in tourism.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The concept of ageism

Ageism is a rather complex concept. There has been growing interest in reviewing and reconceptualizing the concept of ageism and its measurement (Ayalon et al., Citation2019; Iversen et al., Citation2009). To clarify the concept, it is worth going back to early definitions. The first definition is provided by Butler (Citation1969) who considers ageism as a group’s prejudice against another group. In a later definition (Butler, Citation1975), he interpreted the concept of ageism as a process of systematic stereotyping and discrimination directed at certain people simply because they are ‘old’, similarly to racism or sexism. Though ageism is mostly directed at older people, older people may also have negative perceptions of young people (Allan & Johnson, Citation2008; Drury et al., Citation2016; Hutchison et al., Citation2010).

The development of stereotypes and prejudices is greatly influenced by an individual’s previous personal relationships with different social groups, such as minorities and racial groups. This is the starting point of intergroup contact theory, first formulated in the work of Allport (Citation1954). During the past decades, the original ‘contact hypothesis’ has developed into an established theory marked by large number of papers and meta-analyses (Pettigrew, Citation2021). Intergroup contact can have different positive effects including the decrease of prejudice, reduced anxiety, outgroup knowledge, or ingroup identification, and a special importance is attached to cross-group friendships (Pettigrew et al., Citation2011). Studies also show the applicability of the intergroup contact theory in diverse settings and for different groups including age groups (Lytle, Citation2018).

Intergroup contact theory is often used as the dominant theory in explaining the attitude of younger adults toward older adults. In today’s societies, age-based segregation is quite common and amplified by social media. Individuals typically only communicate with their own age group from an early age. Each generation has little opportunity to gain experience of other generations, even though one of the most effective tools for overcoming stereotypes may be interactions between groups (Pettigrew & Tropp, Citation2008).

Contact quality is associated with positive attitude of young people and their behavioral intentions toward older people, while contact frequency doesn’t have similar impact (Bousfield & Hutchison, Citation2010; Drury et al., Citation2016; Visintin, Citation2021). We can conclude that frequent interactions may not be sufficient to change prejudices, but rather the nature of such interactions has the greatest potential to improve people’s attitudes.

Ageism is often investigated in relation with aging anxiety. While ageism expresses how society (young people) perceives a particular age group (older adults), aging anxiety reflects individuals’ feelings about themselves and their future and is associated with fear of death and lower optimism (Barnett & Adams, Citation2018; Lasher & Faulkender, Citation1993). Research results indicate that aging anxiety can be an antecedent of ageism (Bodner et al., Citation2015) as it may be a means of coping with own anxiety about aging. Older adults may remind young people about their own mortality which can lead to negative attitudes (Allan et al., Citation2014). Ageism is also considered a mechanism by which individuals deal with anxiety associated with aging and death, and as a consequence ‘view older adults in a negative light, and create psychological distance’ (Cooney et al., Citation2021, p. 35).

Whether young adults are establishing or avoiding contacts with individuals belonging to a different age group (an outgroup from their perspective) depends also on what they believe the members of the outgroup think of them (Fowler & Gasiorek, Citation2018). Individuals have a desire to be viewed in a positive way and may be concerned how others evaluate them (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013). The concept of metastereotypes refers to the individual’s belief ‘regarding the stereotypes that outgroup members hold about his or her own group’ (Vorauer et al., Citation1998, p. 917). Metastereotypes are also likely to influence individuals’ quality of life and social relations (Fasel et al., Citation2021).

A negative metastereotype can manifest in embarrassment which impacts various areas of everyday life including service interactions (Dahl et al., Citation2001) and is likely to lead to the intention to flee the situation as it is hurting desired identity (Wu & Mattila, Citation2013). Metastereotypes can be considered as a threat and an opportunity as well (Fowler & Gasiorek, Citation2018). Activation of negative stereotypes prevents intergroup contacts, while the generation of positive ones can enhance such contacts.

Gender differences are often investigated in relation to ageism: gender impacts have been confirmed for imagined intergenerational interactions (Prior & Sargent-Cox, Citation2014) and perception of life-style characteristics (Musaiger & D’Souza, Citation2009).

2.2. Ageism and age-based stereotyping in tourism

There is a growing interest in research on stereotyping in the tourism literature. Extant research demonstrates the prevalence of stereotypes in various contexts. One research stream is tourist stereotyping which refers to residents’ preconceptions of tourists (Monterrubio, Citation2018; Tung et al., Citation2020). The results highlight that tourist stereotypes influence the post-travel evaluation of a destination. Countries and destinations are also affected by negative associations and stereotypes which can be a barrier to the inflow of tourists (Avraham, Citation2020) and metastereotypes influence residents’ prosocial behavior (Tung, Citation2019). Gender stereotypes appear in several studies as well. Jiménez-Esquinas (Citation2017) highlights the fact that gender stereotypes may be part of encounters between tourists and hosts. From a different perspective, gender stereotypes apply to the female leader roles in tourism and travel-related services. A study in the hotel sector (Koburtay & Syed, Citation2019) found that gender equality practices significantly enhance the emergence and effectiveness of women leaders.

Age-related stereotyping studies specially focusing on tourism are rare. Luoh and Tsaur (Citation2013) studied how age stereotypes affect tourists’ perceptions of their tour leaders and identified a ‘middle age tour leaders are better’ stereotype. Servers’ age stereotypes were in the focus of a study by Luoh and Tsaur (Citation2011), the results indicate that consumers have a better perception of service quality when the service is delivered by a server with a young appearance than by a server with a middle-aged appearance. To our knowledge, there is only one study specially dedicated to ageism in the hospitality industry in connection with work and employment (Martin & Gardiner, Citation2007).

The lack of research on ageism in the tourism experience context is surprising given the fact that ageism may hinder intergenerational contacts and communication and even lead to the avoidance of certain destinations associated with negative age-based stereotypes, or the avoidance of contact with individuals of a different age group when using hospitality services.

In this study, we introduce and measure the concept ageism in tourism which we define as a form of behavioral intention triggered by age-based stereotypes in relation to customer-to-customer interactions in tourism. Ageism in tourism stems from the belief that certain individuals are just too old or young to take part or contribute to valuable tourist experience. While we acknowledge that ageism can be directed at young and older consumers as well, in a tourism context we propose to focus on ageism directed at older adults given the long-term implication of travel and social interactions for the wellbeing of older people.

2.3. Hypotheses development

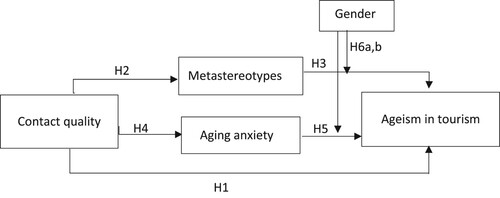

We propose a model that incorporates intergroup contact theory and helps to understand the underlying factors that form ageism in tourism. In the conceptual model presented in , contact quality serves as a focal variable that is responsible for the development of ageism, while metastereotypes and aging anxiety serve as mediators between contact quality and ageism. We also include gender as a moderator variable for the relationships between metastereotypes and ageism in tourism as well as aging anxiety and ageism in tourism.

Our conceptual model highlights the mechanism behind the formation of ageism in tourism. Intergroup contact theory suggests that ageism may have its roots in young people’s prior contacts with older adults. Several studies found that investigating not only the frequency of prior intergenerational contacts but also its quality is important (Hutchison et al., Citation2010; Schwartz & Simmons, Citation2001) and that contact quality decreases ageism (Bousfield & Hutchison, Citation2010; Drury et al., Citation2016; Pettigrew & Tropp, Citation2008). Indeed, the better experience young persons have with older people, the less ageist their behavior will be when using tourism and travel-related service.

H1: Contact quality has a negative effect on ageism in tourism.

H2: Contact quality has a negative effect on the perception of metastereotypes.

In line with this finding, we hypothesize that the more young people assume that older people have negative perceptions of their own age group, the more ageist their behavior will be in case of sharing tourist experience with older people.

H3: The perception of metastereotype has a positive effect on ageism in tourism.

H4: Contact quality has a negative effect on the perception of aging anxiety.

H5: Aging anxiety has a positive effect on ageism in tourism.

H6a: For men the impact of metastereotypes on ageism will be stronger than for women.

H6b: For men the impact of aging anxiety on ageism will be stronger than for women.

H7: The perception of metastereotypes mediates the relationship between contact quality and ageism in tourism.

H8: Aging anxiety mediates the relationship between contact quality and ageism in tourism.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and procedure

We used an online survey to collect data (the Qualtrics survey tool platform) with a convenience sampling approach. The survey was administered in Hungarian. The measurement constructs were translated from English to Hungarian. To assure the reliability of the translation, the backward translation approach (Brislin, Citation1970) was used. Following this procedure, the initial and the back-translated questionnaires were compared resulting in minor modifications.

Our study includes respondents aged 18–35 who had a travel experience during the past three years. The sample size is 530, the proportion of male and females is 41.5% and 58.5%, respectively. On average respondents have made 6.5 domestic trips and 3.8 trips abroad the past three years and more than 80% have at least a secondary education degree, and more than 80% consider their financial conditions as average or better than the average.

3.2. Measures

We concluded from the review of ageism scales (Fraboni et al., Citation1990; Kogan, Citation1961; Rosencranz & McNevin, Citation1969) that the measurement needs to be adapted to a tourism context. We relied on an abbreviated version of the Fraboni Scale of Ageism, particularly on its avoidance dimension (Fraboni et al., Citation1990) and focused only on the negative dimensions. Like most ageism measurements, it contains explicit measurements that can be implemented with our data collection method. The choice of the measuring instrument was determined by its simplicity and clear interpretation of the statements.

The measurement of metastereotypes in the most relevant metastereotype studies is implemented with the manipulation of metastereotypes (Fowler & Gasiorek, Citation2018) with the aim of studying circumstances under which metastereotypes are activated. To create a measurement scale for metastereotype perceptions, we relied on the work by Fowler and Gasiorek (Citation2018) as a conceptual foundation to create a quantitative measurement of metastereotypes.

The measurement of aging anxiety (Drury et al., Citation2016) and contact quality (Hutchison et al., Citation2010) are well established in the literature; we included widely accepted scales in our study. Descriptive statistics for all items are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of study variables.

4. Results

Statistical analyses were performed using IBP SPSS version 26.0 and IBM SPSS AMOS version 26.0. The validity and reliability of measurement instruments were assessed with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Since the measurement of the constructs was based on self-reports of respondents, common method variance had to be considered. According to Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), Harman’s single factor analysis was performed. The exploratory factor analysis resulted in four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. A single factor accounted for 27% of the total variance (lower than the critical value of 50%). Based on these results, we conclude that common method variance is not a serious issue in our study.

4.1. Measurement model

Following data screening and treatment of missing answers, we performed discriminant validity checks, the results are presented in .

Table 2. Discriminant validity of results and correlation matrix.

The composite reliability (CR) of all constructs range between 0.72 and 0.8, which is greater than the suggested threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally, Citation1978). The scales included in our model therefore show a high reliability. Average variance extracted (AVE) range from 0.50 and 0.57 greater than the 0.5 threshold, indicating an acceptable convergent validity. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV). MSV values are smaller than AVE values which indicate acceptable discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2010).

The measurement model was performed with a maximum likelihood estimation. The results indicate a good fit, as all related metrics are acceptable compared to the cut-off values. The Chi-square/df (χ2/df) is less than 2.5; the comparative fit index (CFI) is greater than 0.90; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is not greater than 0.08 (Byrne, Citation2010). All the standardized factor loadings are statistically significant (p < .05) and greater than 0.50 (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The fit indices for the measurement model are: χ2 = 59.915, df = 39; χ2/df = 1.54; p = .017; CFI = 0.988; and RMSEA = 0.032.

4.2. Structural model

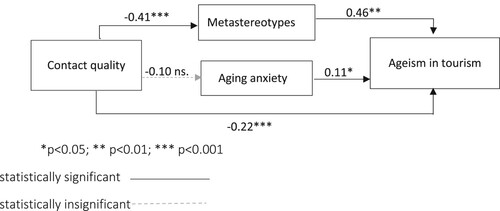

To assess the structural model, we performed SEM analysis. presents the standardized path coefficients. Contact quality is significantly negatively related to ageism in tourism (β = −0.22, p < .001), significantly negatively related to metastereotypes (β = −0.41, p < .001) and insignificantly negatively related to aging anxiety (β = −0.10, p > .05). Thus, H1 and H2 are supported but H4 is not supported. Metastereotypes are significantly positively related to ageism in tourism (β = 0.46, p < .001) and aging anxiety is also significantly positively related to ageism in tourism (β = 0.11, p < .05). presents the parameter estimates.

Table 3. Parameter estimates (standardized coefficients and t-values).

We can conclude that the quality of prior contact with older adults decreases the occurrence of ageism and the perception of metastereotypes in tourism while it does not influence the formation of aging anxiety. Metastereotypes influence ageism in tourism which confirms H3 and to a smaller degree aging anxiety is positively related to ageism in tourism, thus H5 is also supported.

4.3. Mediation analysis

We conducted mediation analysis using the bootstrapping method (Jose, Citation2013) to assess the indirect effects of contact quality on ageism in tourism through metastereotypes and aging anxiety. A 95% bias-correlated confidence interval and 5000 iterations were applied. reports the results of the mediation analysis.

Table 4. Results of the mediation analysis.

The indirect effects of contact quality on ageism in tourism through metastereotypes is estimated as −0.19 with a 95 bias-correlated confidence interval (−0.274; −0.130). This indirect effect is statistically significant which provides support for H7. The indirect effects of contact quality on ageism in tourism through aging anxiety is estimated as −0.01 with a 95 bias-correlated confidence interval (−0.050; 0.113), this indirect effect is statistically insignificant, thus H8 is not supported.

Since both the direct and indirect effects are statistically significant in the case of the path of contact quality -> metastereotypes -> ageism, a partial mediation effect exists (). Therefore, metastereotypes play a partial mediating role in the relationship between contact quality and ageism in tourism.

4.4. Moderation analysis

To test for the moderating effects of gender, we performed multigroup moderation analysis with the help of a χ2 difference test. We created two subsamples for the whole data set using the categorical variable for gender. Group1 included male respondents (N = 220) and Group2 represented female respondents (N = 310). Significant differences were found between male and female respondents regarding the relationship between aging anxiety and ageism in tourism. For male respondents, the effect of aging anxiety on ageism in tourism is stronger than for the whole model (β = 0.29, p < .001), while in the case of female young people the significant relationship disappears (β = 0.03, p = .52). We can conclude that for men aging anxiety is more likely to lead to ageism, while women have a different strategy to cope with anxiety which confirms H6b. No significant differences were found between the two groups regarding the link between metastereotypes and ageism. For both groups, this link is equally strong. Thus, hypothesis H6a is not supported ().

Table 5. Results of multigroup moderation analysis.

5. Discussion

Our study explored the phenomenon of ageism in tourism from young people’s perspectives focusing on the factors that cause young people to display ageist attitudes and behavior. Among the different dimensions of ageism, our focus was directed to the investigation of avoidance behavior, we were particularly interested in getting a better understanding of the mechanisms behind the formation of ageism in tourism.

Contact with older adults, especially the quality of contact referring to pleasant or positive experiences with older adults or even making friends with older adults was assumed to influence ageism in different ways: directly and indirectly through the perceptions of metastereotypes and aging anxiety.

Based on previous studies on intergroup contact theory (Bousfield & Hutchison, Citation2010; Drury et al., Citation2016), we proposed that quality of former contact with older adults may reduce ageism. Our results confirm the existence of a negative direct relationship between previous positive contact with older adults and ageism. It turns out that pleasant experience contributes to the decrease of ageism expressed in terms of avoidance of interaction with older adults. While in the services literature metastereotypes are discussed mainly in relation to embarrassment (Wu & Mattila, Citation2013) we proposed that metastereotypes are an important mediator between contact quality and ageism. Our research results confirmed that hypothesis, as much larger standardized estimates characterized the indirect effect of contact quality on ageism in tourism through metastereotypes, which resulted in significant mediation. This result reinforced the role of metastereotypes (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013) not only influence social relations (Vorauer et al., Citation1998) but also stereotypes, such as ageism. We can conclude that ageism in tourism is mostly triggered by the perception of metastereotypes.

Our second mediation proposing an indirect effect between contact quality and ageism through aging anxiety proved to be insignificant. We note that the measurement of the mediating role of aging anxiety between contact quality and ageism showed mixed results in previous studies (Bousfield & Hutchison, Citation2010). Our assumption that positive contacts provide opportunities for improving knowledge about aging and as a result helping the individual to cope with the personal anxiety of getting closer to death, was not confirmed by our results. It seems that aging anxiety is a deep-rooted psychological state of mind which is hard to prevent. On the other hand, as Bodner et al. (Citation2015) confirmed, our results also demonstrated that aging anxiety increases ageism; the more individuals are characterized by aging anxiety the more they display ageism in the form of avoidance behavior.

Among the demographic characteristics of respondents, gender is often considered in ageism studies (Marques et al., Citation2020), with no conclusive implications. We included gender as a moderator in our model, and the findings suggest that gender moderates the relationship between aging anxiety and ageism in tourism in such a way that for men the relationship between aging anxiety and ageism in tourism is stronger than for women. The explanation lies in differences in coping strategies by gender. Women rather follow an emotion-focused strategy which helps them to handle negative affective states resulting from aging anxiety without engaging in ageist behavior (Matud, Citation2004). In the case of men, the focus on problem-solving approach is more likely to cause the rejection of undesirable future encounters (Kao et al., Citation2017). We also expected a moderating effect of gender in the relationship between metastereotypes and ageism in tourism which was not confirmed by our results. It seems that perception of metastereotypes is a strong predictor of ageism for both men and women and gender-specific coping strategies including positive thinking will not influence its occurrence.

6. Theoretical and practical implications

This study followed a multidisciplinary approach; we relied on tourism and hospitality management, services marketing and management, psychology and social psychology, and gerontology literature. The theoretical contribution of our study expands various academic fields.

First, this study contributes to the ageism literature by introducing the concept of ageism in tourism, proposing a measurement and empirically testing it. Some of our results – such as the link between contact quality and ageism are extensions of existing knowledge into the field of tourism; however, we also bring new insights into ageism research. Metastereotypes have not yet been investigated in relation to ageism. Our results highlight the dominant role of metastereotypes in triggering ageism which could give guidance for intervention efforts to reduce ageism in tourism and other areas of life as well.

Second, we enrich the tourism and hospitality management literature by highlighting the relevance of the concept of ageism. Moreover, this is the first study in the tourism literature that investigates ageism at the individual level based on the intergroup contact theory approach. We believe that our results successfully extend previous findings in ageism studies to a tourism context and give evidence for the need of follow-up studies in the future.

This study has practical implications at individual and organizational levels. We found that intergenerational contacts contribute to the decrease of ageism directly and through the perception of metastereotypes. The success of intergenerational contacts depends largely on communicative behavior between younger and older adults. Communication accommodation theory (Giles & Ogay, Citation2007) draws attention to the need for accommodating communication styles to gain social approval of the outgroup. Individuals should strive to learn how to modify their communication style when interacting with older adults. Volunteering experience could be a means of achieving this objective.

The concept of ageism in tourism has relevance for business organizations, too. The possibility of tensions between customers from different demographic backgrounds poses challenges for service providers in tourism such as hotels and restaurant from two perspectives. First, procedures for handling negative service encounters between different generations should be identified to ensure a pleasant service experience for every guest. Second, service providers should find ways to prevent service customers turning down touristic offers due to negative expectations of undesirable service encounters.

Our findings reveal that the most efficient way to reduce ageism in tourism is through influencing metastereotypes. This can be achieved by selecting the right intervention approach. Types of interventions can be classified into two groups; educational interventions that provide instructions and intergenerational contact interventions that create opportunities for contacts between younger and older adults (Burnes et al., Citation2019). For our purpose, a combination of educational and intergenerational contact interventions could be efficient. Tourism advertising communication should portray older adults in a positive way and service providers should strive to accommodate simultaneously the needs of younger and older adults. Providing opportunities for gaining positive experience with older adults could prevent the formation of metastereotypes and ageism. Service providers in tourism could also find opportunities to influence individuals’ attitudes in early childhood by offering programs or events which would provide a long-lasting positive experience for children. The quality time spent together between the different generations can contribute to the decrease of ageism in later life stages.

Finally, from a broader perspective, sensitization of young people is also the responsibility of education. From an early age, young people should have occasion to spend time with older people as part of their education program and/or their curriculum should include the development of knowledge and attitudes about aging processes.

7. Limitations and future research directions

The limitation of this study relates to its methodology. We investigated one location which allows for limited generalizations. We used a self-administered survey to measure our constructs which despite all our efforts may imply social desirability bias. We focused only on ageism directed to old adults; however, young people may be also subject to prejudices and stereotypes. We asked respondents who had a travel experience in the last three years. An interesting future extension of the research could be to ask tourists during their travel experience and ask feedback on the aspects of ageism. In future studies, different mediators could be included such as intergroup anxiety, or extended contact which would provide further understanding of the formation of ageism in tourism. Implementing a longitudinal study would be particularly interesting: it could investigate the impacts of interventions to decrease ageism. This is equally the responsibility of policy makers, business organizations and individuals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Krisztina Kolos

Krisztina Kolos (PhD) is a full professor of Marketing at the Institute of Marketing and Communication Sciences of Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary. She is involved in several research projects including aging and wellbeing, service development, regional and firm-level competitiveness. Her current research interests are related to services marketing including transformative service research with a special focus on the use of services by the elderly. She actively participates in Hungarian and international conferences. She has written 4 books and several book chapters and has 105 academic publications in Hungarian and English.

Zsófia Kenesei

Zsofia Kenesei (PhD) is full professor of Marketing at the Institute of Marketing and Communication Sciences of Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary. Her main research field is services marketing and digital technology acceptance. She is involved in several research projects, like aging and technology, forced usage of self-service technologies, intercultural service encounters in tourism. She published her findings in international journals and conferences. She has published 6 books and more than 100 scientific articles. Zsofia is the founder president of the Association for Marketing Education and Research and was the national representative of the European Marketing Academy for several years.

References

- Allan, L., & Johnson, J. (2008). Undergraduate attitudes toward the elderly: The role of knowledge, contact and aging anxiety. Educational Gerontology, 35(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270802299780

- Allan, L.J., Emerson, S.D., & Johnson, J.A. (2014). The role of individual difference variables in ageism. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.10.027

- Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Perseus Books.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Avraham, E. (2020). Nation branding and marketing strategies for combatting tourism crises and stereotypes toward destinations. Journal of Business Research, 116, 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.036

- Ayalon, L., Dolberg, P., Mikulionienė, S., Perek-Bialas, J., Rapolienė, G., Stypinska, J., Willińska, M., & de la Fuente-Nunez, V. (2019). A systematic review of existing ageism scales. Ageing Research Reviews, 54, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2019.100919

- Barnett, M.D., & Adams, C.M. (2018). Ageism and aging anxiety among young adults: Relationships with contact, knowledge, fear of death, and optimism. Educational Gerontology, 44(11), 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2018.1537163

- Bodner, E., Shrira, A., Bergman, Y.S., Cohen-Fridel, S., & Grossman, E.S. (2015). The interaction between aging and death anxieties predicts ageism. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.022

- Bousfield, C., & Hutchison, P. (2010). Contact, anxiety, and young people's attitudes and behavioral intentions towards the elderly. Educational Gerontology, 36(6), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270903324362

- Brislin, R.W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Brocato, E.D., Voorhees, C.M., & Baker, J. (2012). Understanding the influence of cues from other customers in the service experience: A scale development and validation. Journal of Retailing, 88(3), 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.01.006

- Burnes, D., Sheppard, C., Henderson, C.R., Wassel, M., Cope, R., Barber, C., & Pillemer, K. (2019). Interventions to reduce ageism against older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 109(8), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305123

- Butler, R.N. (1969). Age-Ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontolgist, 9(4 Part 1), 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.4_Part_1.243

- Butler, R.N. (1975). Why survive? Being old in America. Harper & Row, 1975. pp. 496. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/21.4.341-c

- Byrne, B.M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with Amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cooney, C., Minahan, J., & Siedlecki, K.L. (2021). Do feelings and knowledge about aging predict ageism? Journal of Applied Gerontology. 40(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464819897526

- Cuddy, A.J.C., Glick, P., & Fiske, S.T. (2007). The BIAS Map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

- Dahl, D.W., Manchanda, R.V., & Argo, J.J. (2001). Embarrassment in consumer purchase: The roles of social presence and purchase familiarity. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1086/323734

- Drury, L., Hutchison, P., & Abrams, D. (2016). Direct and extended intergenerational contact and young people's attitudes towards older adults. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(3), 522–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12146

- Eurostat. (2019). Ageing Europe: Looking at the lives of older people in the EU. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/10166544/KS-02-19%E2%80%91681-EN-N.pdf/c701972f-6b4e-b432-57d2-91898ca94893

- Fasel, N., Vauclair, C.M., Lima, M.L., & Abrams, D. (2021). The relative importance of personal beliefs, meta-stereotypes and societal stereotypes of age for the wellbeing of older people. Ageing & Society, 41(12), 2768–2791. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000537

- Finkelstein, L.M., King, E.B., & Voyles, E.C. (2015). Age metastereotyping and cross-age workplace interactions: A meta view of age stereotypes at work. Work, Aging & Retirement, 1(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wau002

- Finkelstein, L.M., Ryan, K.M., & King, E.B. (2013). What do the young (old) people think of me? Content and accuracy of age-based metastereotypes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2012.673279

- Fowler, C., & Gasiorek, J. (2018). Implications of metastereotypes for attitudes toward intergenerational contact. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 23(1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217744032

- Fraboni, M., Saltstone, R., & Hughes, S. (1990). The Fraboni scale of ageism (FSA): An attempt at a more precise measure of ageism. Canadian Journal on Aging, 9(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980800016093

- Giles, H., & Ogay, T. (2007). Communication accommodation theory. In B. B. Whaley & S. Wendy (Eds.), Explaining communication (pp. 325–344). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410614308

- Godovykh, M., & Tasci, A. (2020). Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100694

- Grove, S.J., & Fisk, R.P. (1997). The impact of other customers on service experiences: A critical incident examination of ‘getting along’. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90015-4

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Harris, L.A., & Dollinger, S. (2001). Participation in a course on aging: Knowledge, attitudes, and anxiety about aging in oneself and others. Educational Gerontology, 27(8), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/036012701317117893

- Horner, S., & Swarbrooke, J. (2004). Clubbing and party tourism in the Mediterranean. In S. Horner & J. Swarbrooke (Eds.), International cases in tourism management (pp. 233–241). Routledge.

- Hutchison, P., Fox, E., Laas, A.M., Matharu, J., & Urzi, S. (2010). Anxiety, outcome expectancies, and young people’s willingness to engage in contact with the elderly. Educational Gerontology, 36(10–11), 1008–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601271003723586

- Iversen, T.N., Larsen, L., & Solem, P.E. (2009). A conceptual analysis of ageism. Nordic Psychology, 61(3), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.6288/TJPH.201910_38(5).108095

- Jiménez-Esquinas, G. (2017). ‘This is not only about culture’: On tourism, gender stereotypes and other affective fluxes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1206109

- Jose, P.E. (2013). Doing statistical mediation and moderation. Guilford Press.

- Kao, P.C., Chen, K.T.C., & Craigie, P. (2017). Gender differences in strategies for coping with foreign language learning anxiety. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 45(2), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.5771

- Koburtay, T., & Syed, J. (2019). A contextual study of female-leader role stereotypes in the hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560454

- Kogan, N. (1961). Attitudes toward old people: The development of a scale and examination of correlates. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048053

- Lasher K.P., & Faulkender P.J. (1993). Measurement of aging anxiety: Development of the anxiety about aging scale. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 37(4), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.2190/1U69-9AU2-V6LH-9Y1L

- Luoh, H.F., & Tsaur, S.H. (2011). Customers’ perceptions of service quality: Do servers’ age stereotypes matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.09.002

- Luoh, H.F., & Tsaur, S.H. (2013). The effects of age stereotypes on tour leader roles. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513482774

- Lytle, A. (2018). Intergroup contact theory: Recent developments and future directions. Social Justice Research, 31(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0314-9

- Martin, E., & Gardiner, K. (2007). Exploring the UK hospitality industry and age discrimination. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19(4), 309-318. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110710747643

- Marques, S., Mariano, J., Mendonça, J., De Tavernier, W., Hess, M., Naegele, L., Peixeiro, F., & Martins, D. (2020). Determinants of ageism against older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2560), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072560

- Matud, M.P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1401–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010

- Monterrubio, C. (2018). Tourist stereotypes and servers’ attitudes: A combined theoretical approach. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 16(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2016.1237518

- Musaiger, A.O, & D’Souza, R. (2009). Role of age and gender in the perception of aging: A community-based survey in Kuwait. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 48(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2007.10.002

- Nicholls, R., & Mohsen, M.G. (2015). Other customer age: Exploring customer age-difference related CCI. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(4), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-04-2014-0144

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Pettigrew, T.F. (2021). Advancing intergroup contact theory: Comments on the issue’s articles. Journal of Social Issues, 77(1), 258–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12423

- Pettigrew, T.F., & Tropp, L.R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504

- Pettigrew, T.F., Tropp, L.R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Jeong-Yeon, L., & Podsakoff, N.P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prior, K., & Sargent-Cox, K.A. (2014). Students’ expectations of ageing: An evaluation of the impact of imagined intergenerational contact and the mediating role of ageing anxiety. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.06.001

- Rosencranz, H.A., & McNevin, T.E. (1969). A factor analysis of attitudes toward the aged. Gerontologist, 9(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.1.55

- Schwartz, L.K., & Simmons, J. P. (2001). Contact quality and attitudes toward the elderly. Educational Gerontology, 27(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270151075525

- Smith, M.K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

- Stončikaitė, I. (2021). Baby-boomers hitting the road: The paradoxes of the senior leisure tourism. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2021.1943419

- Tung, V.W.S. (2019). Helping a lost tourist: The effects of metastereotypes on resident prosocial behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518778150

- Tung, V.W.S., King, B.E.M., & Tse, S. (2020). The tourist stereotype model: Positive and negative dimensions. Journal of Travel Research, 59(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518821739

- Visintin, P.E. (2021). Contact with older people, ageism, and containment behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2504

- Vorauer, J.D., Main, K.J., & O’Connell, G.B. (1998). How do individuals expect to be viewed by members of lower status groups? Content and implications of meta-stereotypes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 75(4), 917–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.917

- Wu, L., & Mattila, A. (2013). Investigating consumer embarrassment in service interactions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.08.003