?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective: The rapid increase of cell-free fetal DNA analysis for Down syndrome screening requires evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT). Several studies show that the quality of many guidelines is low and there are still many health areas where this quality is not systematically evaluated. Given the absence of research, in the NIPT field, we used an internationally validated tool to evaluate a set of three NIPT practice guidelines and to look at dimensions that can be improved.

Methods: Four appraisers, experts in prenatal screening, evaluated three main NIPT guidelines published in the last 2 years using the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II), a tool specifically designed for guideline quality appraisal.

Results: Guidelines scored higher in domains related with scope, purpose, and clarity of presentation, and lower in stakeholder involvement and rigor of development. Intradomain items evaluation showed asymmetries between guidelines. The UK-NSC was the guideline with the best scores.

Discussion: Several areas of NIPT guidelines, such as stakeholders involvement, selection of supporting evidence, external reviews, updating processes, and competing interests disclosure, can be improved. Appraisers recommend modifications to all NIPT guidelines that can lead to substantial improvements in their methodological quality and subsequently make a contribution to prenatal screening improvement.

Introduction

The recent use of cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) in maternal peripheral blood showed a significantly higher detection rate and lower false positive rate for detection of trisomy 21 in general pregnant women, in singleton pregnancies [Citation1,Citation2]. After its identification in 1997 [Citation3], the rapid increase of cffDNA analysis utilization, and the asymmetries in its use, both across and within countries, emphasized the need to develop and implement, at national and international levels, better quality control mechanisms, including through evidence-based guidelines for noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) [Citation4]. In the past few years, several expert groups have also issued documents addressing specific concerns, although most documents were not systematically developed as clinical practice guidelines [Citation5–8].

Practice guidelines (PGs) are documents built to help professionals in making decisions about diagnosis and care, according to the best scientific evidence available [Citation9]. The concept of PGs use is today deeply disseminated throughout all health contexts [Citation10], mainly due to the exponential growth seen in the number of published Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), in the last decades [Citation11,Citation12].

This growth poses a set of challenges [Citation13], and several studies show that the quality of many guidelines is low [Citation12,Citation14,Citation15], the methodology is modest and there are many variations across guidelines dedicated to the same subject [Citation16]. Even in WHO guidelines there is infrequent use of systematic reviews, an absence of systematic guideline development methodology and an overestimation of expert opinion [Citation17,Citation18].

These issues led several groups to develop tools to fulfill an emerging need and to tackle associated challenges [Citation19]. One of these groups developed and validated an instrument named AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation), to assess the quality of CPGs [Citation20]. The AGREE Instrument evaluates the process of PGs development and the quality of reporting [Citation21]. After being applied and studied in a broad range of health areas [Citation14,Citation22–25], is now in its second version [Citation26]. However, and despite the validation, dissemination and use of tools like AGREE, there are still many health areas where the quality of guidelines is not systematically evaluated [Citation12,Citation27].

Also in the Laboratory Medicine field, CPGs became increasingly important to improve the effectiveness of disease diagnosis and monitoring [Citation12,Citation27,Citation28], albeit only a few guidelines were evaluated [Citation29–31]. When we look at the NIPT field the scenario is even sparser, with the publication of only one nonstructured study related with NIPT guidelines appraisal [Citation32].

Given the absence of studies in this area and the exponential development of NIPT in the recent years, we believe that evaluating NIPT guidelines can be key to improve existing guidelines and to promote the correct use of prenatal screening.

This study was designed to evaluate three NIPT practice guidelines and to look at dimensions that can be improved, when a validated appraisal tool is used. Additionally, the study can contribute to the design of future guidelines in this field.

Materials and methods

Guideline search

The authors searched the main health databases (PubMed, CrossRef, ScienceDirect and Web of Science), using the following terms: guidelines OR practice guidelines OR clinical practice guidelines OR recommendations OR policy statement OR consensus statement OR position paper, AND NIPT or NIPS (Noninvasive prenatal screening), OR cffDNA OR cfDNA. We also looked at relevant agencies that produce CPGs in the NIPT field.

Inclusion criteria were: guidelines published in the last 2 years, NIPT related, public endorsement by scientific societies or professional bodies and online availability. Three guidelines were assessed: (1) United Kingdom National Screening Committee (UK-NSC) Recommendation [Citation33] and supporting documents [Citation34–38], (2) American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Management (ACOG) Guideline, [Citation39] and (3) American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Statement [Citation40].

Assessment instrument

The AGREE II is a tool used to assess the methodological quality of PGs and has been tested for its validity and reliability [Citation41,Citation42], providing also a strategy to guideline development [Citation18]. Each appraiser answers 23 questions assessing guidelines components, using a 7-point Likert scale (one for “strongly disagree” to seven for “strongly agree”), based on instructions, detailed criteria and examples for each item, available in the manual. The tool has six domains to assess the quality related to: I – Scope and purpose, II – Stakeholder involvement, III – Rigour of development, IV – Clarity of presentation, V – Applicability and VI – Editorial independence. Scores given by each expert are used to calculate aggregated scores per domain, translated into percentages using the formula described below.

The appraisers are additionally asked to provide comments to justify their ratings and also to rate the guideline globally (Overall Assessment), using the same Likert scale. Finally, they are asked to state if they would: (a) recommend the guideline, (b) recommend it with modifications, or (c) not recommend it at all.

Appraisers

The group of four appraisers included experts in prenatal screening (two Clinical Pathologists, MDs and two Biochemists), all with extensive laboratory experience. In order to assure the correct use of AGREE II across appraisers, all experts attended training sessions supported by the Tutorial and Practice Exercises modules, available online (www.agreetrust.org). The selected NIPT practice guidelines were evaluated by all experts participating in the study (MJS, MA, GC, RR), using the instrument and the User’s Manual.

Scores and data analysis

Domain scores were determined according to AGREE II instructions. Percentages for each domain were calculated by summing all four appraiser ratings per item, within each domain (obtained score), and converting the final score into a percentage, using the following formula:

Obtained score = sum of all items scores from all four appraisers, by domain

maximum possible score = 7 (strongly agree) × Y (items within domain) × 4 (appraisers)

minimum possible score = 1 (strongly disagree) × Y (items within domain) × 4 (appraisers)

Moreover, final scores were extracted per item, enabling a detailed analysis of strengths and weaknesses within domains, and a more comprehensive comparison between guidelines.

To define a high-quality guideline, we used a three-step system with thresholds similar to other AGREE studies, (Low-quality, below 50%, Medium-quality, between 50 and 74% and High-quality, between 75 and 100%). A high-quality guideline is here defined as any guideline where the majority of domains scores are above 74% and the overall score is also 75% or higher (4 raters combined).

The reliability between appraisers was calculated through intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Tabulation and analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, version 15 and SPSS Statistics, version 21.

Results

The overall assessment scores show that the UK-NSC guideline has a considerable higher result (88%), when all four appraiser’s assessments are combined (). The other two guidelines have lower overall scores, ACOG with 50% and ACMG with 58%.

Table 1. Guidelines domains scores and overall assessment.

Likewise, the UK-NSC guideline totalize highest scores for domains 1 (99%), 2 (61%), 3 (74%), 4 (96%, ex-aequo with ACMG guideline), and 5 (83%). The highest score for Domain 6, Editorial independence, was credited to ACMG guideline (83%). Lower scores, in the majority of all domains, were given to ACOG guideline, namely domains 1 (74%), 2 (43%), 4 (89%), 5 (30%), and 6 (25%). ACMG scored lowest (36%) in Domain 3, Rigour of Development. Globally, the highest domain score was given to UK-NSC Scope and Purpose (99%), and the lowest score to ACOG Editorial Independence (25%).

Complementary to the results already described, we can look at additional trends. There are approximate higher scores for all guidelines in domain 4 – Clarity of Presentation (UK-NSC 96%, ACOG 89%, ACMG 96%, SD = 4), and lower scores in domain 2 – stakeholder Involvement (UK-NSC 61%, ACOG 43%, ACMG 51%, SD = 9). Higher discrepancies between scores can be found in domains 5 – applicability, ranging from 30% (ACOG) to 83% (UK-NSC), SD =27, and 6 – editorial Independence, ranging from 25% (ACOG) to 83% (ACMG), SD =32.

Additionally to domains assessment, the results per item, within each domain, provide a supplementary reading on guidelines attributes. These results (), divided in three categories labeled as: + below 50%, ++ between 50 and 74%, and +++ above 74%, show that Domain 4 – Clarity of Presentation is the only domain where the three guidelines have all items rated 75% or more. These higher scores are followed by domain 1 – Scope and Purpose, where only ACOG target population description is rated below 75%.

Table 2. Guidelines items scores, per domain.

In Domain 2 – Stakeholder involvement, all guidelines have one item rated below 50%. Additionally, ACOG and ACMG guidelines don’t have items rated 75% or above.

Regarding Domain 6 – editorial Independence, all items from the UK-NSC guideline obtained scores of 75% or above. The ACMG guideline scored below 75% in the item referring to the influence of the funding body view in the guideline content, and above in recording and addressing the competing interests of the guideline development group. Still in Domain 6, the ACOG guideline scored below 50% in both items described.

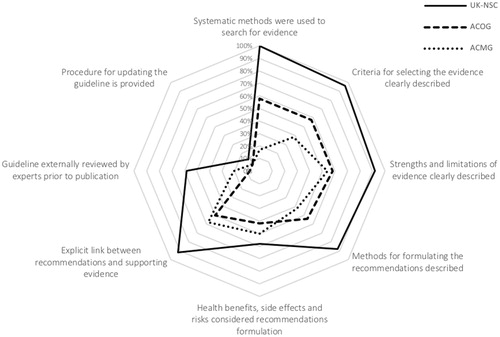

Particularly complex and pivotal domains, such as domains 3 and 5, require a more detailed look at items scores. Full items scores for Rigour of Development (), show diverse results between guidelines, regarding: (a) the methods used to search supporting evidence (UK-NSC 100%, ACOG 58% and ACMG 17%), (b) the description of the criteria for selecting the evidence (UK-NSC 96%, ACOG 58% and ACMG 38%), and (c) the methods used in the recommendations formulation (UK-NSC 88%, ACOG 54% and ACMG 42%).

In what concerns the description of strengths and limitations of the body of evidence (UK-NSC 92%, ACOG 58% and ACMG 54%), and the linkage between this evidence and the issued recommendations (UK-NSC 92%, ACOG 50% and ACMG 58%), the UK-NSC guideline has, clearly, higher scores, with ACOG and ACMG results ranging from 50 to 58%, for the same two items.

For the group of items with lower scores in this domain, specifically the consideration of health benefits, side effects and risks when formulating recommendations, the highest score is 58% (UK-NSC), followed by ACMG (50%) and ACOG (42%). The item related with guidelines external review, prior to its publication, has also low scores (UK-NSC 58%, ACOG 8% and ACMG 21%), with two guidelines scoring noticeably below 50%. The last item in this domain, related with the existence of a procedure for updating the guideline, has the lowest scores for all guidelines (UK-NSC 46%, ACOG 8%, and ACMG 8%), where all are below 50%.

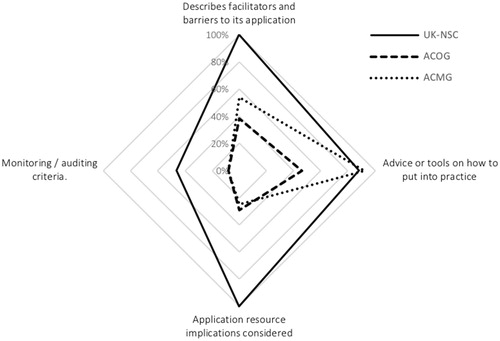

In domain 5 – Applicability (), we can clearly see that the UK-NSC guideline has higher scores for most items, except for the one related to providing the tools or advice on how to put the recommendations into practice (UK-NSC 88%, ACOG 46%, and ACMG 92%). Additionally, the scores are more dissimilar between all guidelines for the item pertaining to the description of facilitators and barriers to implementation (UK-NSC 100%, ACOG 38%, and ACMG 54%).

The item associated with resources implications to apply the recommendations, has the biggest range between items in this domain, where the UK-NSC guideline scored 100%, while the ACOG and the ACMG guidelines scored 29 and 25%, respectively.

The lowest scoring can be found in the item linked with the existence of monitoring and audit criteria for the guidelines, where all scored below 50% (UK-NSC 46%, ACOG 8%, and ACMG 8%).

results show that three out of four experts recommend the UK-NSC guideline without modifications and one makes the same recommendation, but with modifications. Regarding the ACMG guideline, all experts recommend it with modifications. The ACOG guideline is not recommended by one expert, while the remaining three recommend it, with modifications.

Table 3. Appraiser recommendations for the use of guidelines.

Inter-rater reliability, between all raters, was calculated by means of Intra Class Correlation. The results for the three guidelines were: UK-NSC ICC = 0.811, ACOG ICC = 0.757 and ACMG ICC = 0.794.

Discussion

Clinical practice guidelines quality assessment represents one of the most important components of healthcare quality improvement processes. It highlights the need to understand that specific tools must be used to make contextualized assessments, and the need to accept that our expertise is only one of the key prerequisites to promote sustained quality improvement of care.

The domain assessing Scope and Purpose was one of the domains with the highest scores. Whilst we can find high scores for this domain in single guidelines studies [Citation23,Citation43,Citation44] and systematic reviews [Citation12], NIPT guidelines topped most evaluations made with AGREE II, suggesting that the potential health impact on patients and the description of the health questions [Citation45,Citation46] were highly considered.

The overall scores for stakeholder involvement, focused on broad participation and users views [Citation47] were low. The UK-NSC guideline scored very high in the inclusion of individuals from all relevant professional groups [Citation37,Citation38], accordingly with current consensus [Citation48], but very low in the definition of target users, with only a scarce mention to this key component [Citation9,Citation49].

As in similar studies [Citation9,Citation18] the views and preferences of target population still remain a challenge and a weakness in many guidelines, but patients dimensions must be accounted for into decisions, as there is no one better qualified than families and patients to describe difficulties or disabilities. This view [Citation36], accounts both for stakeholder independency and patient participation, as recommended by WHO [Citation18].

In the domain Rigour of Development, dedicated to methodology and use of evidence [Citation47], the biggest differences were found in the methods to search the evidence, where vulnerabilities can compromise guidelines main goal of improving the quality of care [Citation48]. The UK-NSC was the CPG that best performed in this item, confirming NHS strong methodological tradition in research [Citation50], but the assessment shows further liabilities related with the criteria for selecting the evidence and the methodology to formulate recommendations, influencing recommendations variability [Citation16]. The results follow a similar pattern when we look at strengths and limitations of the evidence and the link between evidence and recommendations, suggesting a less structured guideline development methodology [Citation48].

All guidelines inadequately considered health benefits, adverse effects and risks, key factors to increase the odds for better implementation [Citation11] and vital in the prenatal screening area, given the professionals judgement call variability [Citation51].

The absence of a thorough external review process, prior to publication, was also an important finding, as it represents a further vulnerability to implementation. Additionally, only one guideline informed about updating procedures, a shortcoming identified before [Citation17], that deters guidelines revision according to a predefined timeline [Citation11], through a standing panel that reviews new literature and update changes [Citation47].

The domain dedicated to Clarity of Presentation was the one where all three guidelines scored higher. Though somehow expected, based on previous results, both from national societies [Citation52] and international organizations [Citation18], it is important to highlight that these results suggest a special attention given by all NIPT guidelines to this domain.

Regarding Applicability, the mean score was one of the lowest overall, suggesting difficulties to advise on how to apply recommendations. Further developments should consider this to improve adoption [Citation53]. ACOG and ACMG guidelines also scored poorly in the description of barriers to implementation and cost implications, similarly to other studies [Citation9]. Contrariwise, the UK-NSC guideline targets several barriers (eg resources and financial costs), necessary to address contextual factors that may hinder applicability [Citation18].

Pilot testing is key to ensure that guidelines can be put into practice, but only the UK-NSC and the ACMG reported results of a pilot test, scoring equivalently to previous evaluations [Citation9]. Assessing applicability improves guidelines uptake and sustained use, establishing its quality in real world settings [Citation14], however none of the three guidelines reported outcome measures for implementation or monitoring criteria. Our results show that, like in other comparable studies, all evaluated guidelines can considerably improve their quality regarding applicability [Citation9].

In what concerns Editorial Independence, it must be extolled that ACMG guideline top scored by explicitly disclosing competing interests. In 2000, Grilli evaluated 431 practice guidelines and found that 67% did not report the type of professionals involved in the guideline development [Citation54], similar to other studies [Citation55]. Furthermore, the ACMG guideline scored fairly in the item referring to the funding body influence and ACOG guideline scored below 50% in both items. Disclosure is key to assess the potential influence of conflict of interest and for the reputation of institutions that want their guidelines to be considered [Citation49].

Limitations in the study included difficulties defining the concept of guideline and the instrument characteristics. AGREE II is an internationally accepted gold standard for guidelines appraisal [Citation56], and the most comprehensively validated tool [Citation57,Citation58], but we must assume some degree of subjectivity in the results, namely the overall assessment and recommendations [Citation59]. Additionally, the instrument does not include information about how to implement new or updated CPGs, a process critical to quality of care improvement, that would help implementers and clinicians. Other limitation was the fact that all appraisers work in the same laboratory and might be influenced by the organizational culture, despite all measures taken to keep the process blind between appraisers.

This study allowed us to evaluate guidelines of an important and rapidly evolving health area, that haven’t been evaluated in a structured way before. The results showed that several areas of NIPT guidelines can be improved significantly, such as stakeholders involvement, selection of supporting evidence, external reviews and updating processes. Additionally, it is pivotal to improve the applicability necessary to implementation and sustainability.

The study also highlighted specific vulnerable areas within domains. This allowed us to conclude that there are key items where scores vary notably between NIPT guidelines and that the UK-NSC is the guideline with the highest quality.

Professional associations should adopt systematic procedures for guideline development according to known evidence and with the participation of a broad range of stakeholders.

There is a need for further improvement, not only in traditional core components, already highlighted, but also in dimensions such as editorial independence, including competing interests disclosure.

Practice guidelines aim to provide a valuable aid in making complex clinical decisions and when rigorously developed have the potential to enhance those decisions and healthcare quality. Almost all appraisers recommended all three NIPT guidelines with modifications that can lead to a substantial improvement in their methodological quality and subsequently make a contribution for prenatal screening improvement. Actions should be taken to review and improve these important guidelines for NIPT, involving all key stakeholders and using quality appraisal validated tools.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ana Guia Pereira for her contribution to the guideline selection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Gil MM, Accurti V, Santacruz B, et al. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:302–314.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:799–808.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350:485–487.

- Minear MA, Lewis C, Pradhan S, et al. Global perspectives on clinical adoption of NIPT. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35:959–967.

- Jani J, Rego de Sousa MJ, Benachi A. Cell-free DNA testing: how to choose which laboratory to use?. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:515–517.

- Buchanan A, Sachs A, Toler T, et al. NIPT: Current utilization and implications for the future of prenatal genetic counseling. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:850–857.

- Gratacós E, Nicolaides K. Clinical perspective of cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidies. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2014;35:151–155.

- Dondorp W, de Wert G, Bombard Y, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy and beyond: challenges of responsible innovation in prenatal screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1438–1450.

- Lo Vecchio A, Giannattasio A, Duggan C, et al. Evaluation of the quality of guidelines for acute gastroenteritis in children with the AGREE instrument. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:183–189.

- Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–1322.

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on standards for developing trustworthy. Clinical practice guidelines, graham R1. Clinical practice guidelines We Can Trust – Report Brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011.

- Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e58.

- Knai C, Brusamento S, Legido-Quigley H, et al. Systematic review of the methodological quality of clinical guideline development for the management of chronic disease in Europe. Health Policy. 2012;107:157–167.

- Burgers JS, Cluzeau FA, Hanna SE, et al. Characteristics of high-quality guidelines: evaluation of 86 clinical guidelines developed in ten European countries and Canada. Int J Tech Assessment Health Care. 2003;19:148–157.

- Armstrong JJ, Goldfarb AM, Instrum RS, et al. Improvement evident but still necessary in clinical practice guideline quality: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:13–21.

- Vigna-Taglianti F, Vineis P, Liberati A, et al. Quality of systematic reviews used in guidelines for oncology practice. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:691–701.

- Oxman A, Lavis J. Use of evidence in WHO recommendations. Lancet. 2007;369:1883–1889.

- Polus S, Lerberg P, Vogel J, et al. Appraisal of WHO guidelines in maternal health using the AGREE II assessment tool. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38891.

- Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, et al. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–530.

- AGREE C. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23.

- Grol R, Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS. Clinical practice guidelines: towards better quality guidelines and increased international collaboration. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:S4–SS8.

- MacDermid JC, Brooks D, Solway S, et al. Reliability and validity of the AGREE instrument used by physical therapists in assessment of clinical practice guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:18.

- Cates JR, Young DN, Bowerman DS, et al. An independent AGREE evaluation of the Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines. Spine J. 2006;6:72–77.

- Kinnunen-Amoroso M, Pasternack I, Mattila S, et al. Evaluation of the practice guidelines of Finnish Institute of Occupational Health with AGREE instrument. Ind Health. 2009;47:689–693.

- Nast A, Spuls P, Ormerod A. A critical appraisal of evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: “AGREE-ing”on a common base for European evidence-based psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:782–787.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Agree II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med. 2010;51:421–424.

- Legido-Quigley H, Panteli D, Brusamento S, et al. Clinical guidelines in the European Union: mapping the regulatory basis, development, quality control, implementation and evaluation across member states. Health Policy. 2012;107:146–156.

- Tozzoli R, Bizzaro N, Tonutti E, et al. Guidelines for the laboratory use of autoantibody tests in the diagnosis and monitoring of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:316–324.

- Don-Wauchope AC, Sievenpiper JL, Hill SA, et al. Applicability of the AGREE II instrument in evaluating the development process and quality of current National Academy of clinical biochemistry guidelines. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1426–1437.

- Française de Biologie Clinique (SFBC), Fonfrède M, Couaillac JP, et al. Critical appraisal of microbiology guidelines endorsed by two professional organisations: Société Française De Microbiologie (SFM) and American Society of Microbiology (ASM). EJIFCC. 2012;23:28–32.

- Nachamkin I, Kirn TJ, Westblade LF, et al. Assessing clinical microbiology practice guidelines: American society for MicrobiologyAd HocCommittee on evidence-based laboratory Medicine practice guidelines assessment. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:3183–3193.

- CADTH. Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of the cost effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa, (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014.

- UK National Screening Committee. UK NSC Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) Recommendation 2016; 1–1 Available from: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/fetalanomalies

- Chitty L, Cameron L, Daley R, et al. RAPID non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) evaluation study. In: National Institute for Health Research, editor. Executive summary. 2015. p. 1–8. Available from: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/fetalanomalies

- UK National Screening Committee. Consultation for Cell-Free DNA Testing in the First Trimester in the Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme 2015:1–6. Available from: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/fetalanomalies

- UK National Screening Committee. Screening for cfDNA in pregnancy- an evidence review. Compiled Comments 2016:1–151. Available from: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/fetalanomalies

- UK National Screening Committee. UK National Screening Committee. cfDNA testing in the fetal anomaly screening programme – Annexes 2015;1–25. Available from: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/fetalanomalies

- Taylor-Phillips S, Freeman K, Geppert J, et al. Systematic Review and Cost-Consequence Assessment of Cell-Free DNA Testing for T21, T18 and T13 in the UK – Final Report. In: UK National Screening Committee, editor. p. 1–175.

- Practice bulletin. No. 163: screening for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e123–e127.

- Gregg AR, Skotko BG, Benkendorf JL, et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: a position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18:1056–1065.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: Performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ. 2010;182:1045–1052.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182:E472–E478.

- Zhang X, Zhao K, Bai Z, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypertension: evaluation of quality using the AGREE II instrument. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16:439–451.

- Tejani T, Mubeen S, Seehra J, et al. An exploratory quality assessment of orthodontic clinical guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39:654–659.

- Hoffmann-Eszer W, Siering U, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Is there a cut-off for high-quality guidelines? A systematic analysis of current guideline appraisals using the AGREE II instrument. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;95:1–25.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Agree II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842.

- AGREE Next Steps Consortium. The AGREE. II Instrument (Electronic Version) 2009:1–56 [cited 2017 Mar 10]; Available from: http://www.agreetrust.org

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Graham R, Mancher M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Shekelle P, et al. Developing clinical practice guidelines: target audiences, identifying topics for guidelines, guideline group composition and functioning and conflicts of interest. Implementation Sci. 2012;7:1–1.

- Mackenzie IS, Wei L, Paterson KR, et al. Cluster randomized trials of prescription medicines or prescribing policy: public and general practitioner opinions in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:354–361.

- Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangl J. Are guidelines following guidelines? the methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA. 1999;281:1900–1905.

- Sabharwal S, Patel NK, Gauher S, et al. High methodologic quality but poor applicability: assessment of the AAOS guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1982–1988.

- Sabharwal S, Patel V, Nijjer SS, et al. Guidelines in cardiac clinical practice: evaluation of their methodological quality using the AGREE II instrument. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:315–322.

- Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, et al. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet. 2000;355:103–106.

- Taylor R, Giles J. Cash interests taint drug advice. Nature. 2005;437:1070–1071.

- Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Do guidelines offer implementation advice to target users? A systematic review of guideline applicability. BMJ Open. 2015;55:e007047.

- Siering U, Eikermann M, Hausner E, et al. Appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: A systematic review. Plos One. 2013;8:e82915–e82915–5.

- Radwan M, Akbari Sari A, Rashidian A, et al. Appraising the methodological quality of the clinical practice guideline for diabetes mellitus using the AGREE II instrument: a methodological evaluation. JRSM Open. 2017;8:205427041668267.

- Hoffmann-Eszer W, Siering U, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Guideline appraisal with AGREE II: Systematic review of the current evidence on how users handle the 2 overall assessments. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174831–e0174831–15.