Abstract

Objective

The objective of the study was to evaluate the effect of individual nutrition education on nutritional knowledge, attitude, practices, adherence to iron-folic acid intake, and hemoglobin levels among anemic South Indian pregnant women.

Methods

This intervention study was conducted from December 2020 to March 2021 in a secondary care level women and child hospital at Puducherry, India. The intervention group (n = 59) and comparison group (n = 58) included mild to moderately anemic pregnant women attending antenatal clinics (Mild anemia – Hb levels between 10.0 and 10.9 g/dL, Moderate anemia – Hb levels between 7.0 and 9.9 g/dL). Individual nutrition education intervention and SMS alerts for four weeks were given to the pregnant women. Baseline data and hemoglobin levels were measured at the time of enrollment. Maternal adherence to iron-folic acid tablets (IFA) was assessed using a five-item Medical Adherence Rating Scale (MARS-5). End line data were collected after 4 weeks of nutrition education intervention.

Results

At the end of the individual nutrition education intervention, there was a significant improvement in the hemoglobin level in the intervention group compared to the comparison group (p < .02). The change in the knowledge, attitude and practice scores regarding nutritional management of anemia and maternal adherence to iron-folic acid intake were significantly high in the intervention group over the comparison group (p < .001).

Conclusion

Individual nutrition education was significantly associated with improved nutritional knowledge, attitude, practice, adherence to IFA intake and hemoglobin levels in anemic pregnant women.

Introduction

Anemia is a major public health problem among pregnant women. World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women is 38.2% worldwide [Citation1]. The prevalence of anemia among Indian pregnant women is 50.3% [Citation2]. Anemia is defined as a hemoglobin concentration less than 11 g/dl. It is measured as severe when hemoglobin level is less than 7.0 g/dl, moderate when hemoglobin level between 7.0 and 9.9 g/dl, and mild when hemoglobin is from 10.0 to 10.9 g/dl [Citation3]. It could lead to adverse maternal and fetal outcomes such as intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, maternal and fetal mortality [Citation4].

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia among Indian pregnant women [Citation5]. Thus, the government of India under the National Iron Plus Initiative (NIPI), provides a daily dose of iron and folic acid tablet (IFA) of 100 mg of iron with 0.5 mg of folic acid to all pregnant women for 100 days [Citation6]. Nationally representative data collected as part of National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) from pregnant women aged 15–49 years in the NFHS-4 (2015–2016) and NFHS-5 (2019–2021) reported that improved adherence to the IFA intake from 30.3 to 44.1% among antenatal pregnant women. However, the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women has increased from 50.4 to 52.2% [Citation7,Citation8].

Further, possible explanations for this continuing burden of anemia, are attributed to dietary and environmental reasons. The dietary reasons include the low bioavailability of iron in the dietary sources, poor selection or consumption of iron-rich foods, and increased intake of phytate and polyphenol-rich food which inhibits iron absorption [Citation9,Citation10]. Consumption of unsafe water, poor sanitation and hygiene (WASH) causes environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) “leaky gut” syndrome and hookworm infestation are the possible environmental reasons for anemia in pregnancy [Citation10].

Knowledge about appropriate nutrition during pregnancy is important for the well-being of both mother and fetus [Citation11]. Nutrition education is the most used strategy to improve the nutritional status of pregnant women and is found to be associated with improved hemoglobin levels in the anemic pregnant women in other populations [Citation12,Citation13]. Studies reported that Indian pregnant women had inadequate knowledge regarding the nutritional management of anemia [Citation14]. Hence, regular nutrition education on the management of anemia during their antenatal visits may help to reduce the impact of anemia. The study aimed to evaluate the effect of individual nutrition education on nutritional knowledge, attitude, practices, adherence to iron-folic acid intake, and hemoglobin levels among anemic South Indian pregnant women.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Human studies). Written informed consent was obtained from the anemic pregnant women included in the study. Confidentiality and privacy of the participants were maintained.

Study design and participants

This was a quasi-experimental study involving pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic with mild and moderate anemia. The study was conducted from December 2020 to March 2021 with one intervention and one comparison group in a secondary care level Women and Child hospital at Puducherry, India. Pregnant women aged 18 years or above, between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, mild to moderately anemic (Mild anemia – Hb levels between 10.0 and 10.9 g/dL, Moderate anemia – Hb levels between 7.0 and 9.9 g/dL) [Citation1] were included in the study. Pregnant women with medical conditions like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid disease, renal disease, cardiopulmonary disease, and severe anemia were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling method

We enrolled a total of 60 anemic pregnant women in both the intervention and comparison groups. Based on a previous study, the prevalence of anemia among antenatal pregnant women at Puducherry as 26% [Citation15]. The sample size was adequate at 95% confidence interval, 80% power, alpha value of 0.05 calculated using OpenEpi online software** version 3.2 while also accounting up to 10% attrition.

Anemic pregnant were consecutively enrolled and assigned to intervention and comparison group purposively. The odd-numbered study subjects were assigned to receive nutrition education in the intervention group in addition to the routine hospital care and even-numbered study subjects received only routine hospital care in the comparison group.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of video-assisted nutrition education and leaflet distribution to the intervention group in addition to the routine hospital care and only routine hospital care to the comparison group during the study period. Routine hospital care includes maternal weight measurement, abdominal examination, blood pressure, Hb, blood sugar, urine albumin and sugar testing and provision of 2 tablets of IFA daily for mild and moderate anemic pregnant women. Nutrition education materials were prepared in Tamil (local language) by the Principal Investigator. It was developed based on the manual of “Dietary Guidelines for Indians” published by the Indian Council of Medical Research [Citation16] and Information Education Communication materials (Anemia Mukt Bharat Programme) published by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India [Citation17]. The information in the video and leaflet were consisted of causes of anemia, signs, and symptoms, effects on mother and her fetus, iron-rich food items (affordable and locally available), enhancers and inhibitors of iron absorption, iron-rich food-based diet plan, and intake of recommended IFA tablets. After the baseline data collection, individual nutrition education was delivered by the principal investigator with the use of laptop in a separate room in order to avoid the contamination with the comparison group. At the end of the session, leaflet was given to the pregnant women of the intervention group. Further, an SMS alert was sent twice a day for four weeks as reinforcement of regular intake of iron-rich foods and IFA tablets in the intervention group.

Study tools

Semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect demographic and obstetrical variables. Pretested structured questionnaire, checklist, and Likert scale were used to collect data knowledge, practice, and attitude regarding nutritional management of anemia. The maternal nutritional knowledge questionnaire consisted of 30 questions, for each correct answer a score of 1 was given while the incorrect answer was given a score of 0. Scores from 0 to 10, 11 to 20, and 21 to 30 were considered as poor, average, and good knowledge respectively. A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess the maternal attitude regarding nutritional management of anemia in pregnancy. It consisted of 10 statements with an overall score range between 10 and 50. Items were respectively scored from 1 – Strongly disagree, 2 – Disagree, 3 – Neutral, 4 – Agree, and 5 – Strongly agree. Scores from 34 to 50, 17 to 33, and 16 to 10 were considered as positive, neutral, and negative attitudes respectively. Maternal practices regarding nutritional management of anemia were assessed by a checklist of 15 questions. Each good practice has 1 mark and poor practice has 0 marks. Scores from 0 to 5, 6 to 10, and 11 to 15 were considered as poor, average, and good practice respectively.

Details on consumption of IFA tablet per week were recorded during the data collection. Consumption of IFA tablets at least 5 days a week by anemic pregnant women was considered as adherent [Citation18,Citation19]. Also, maternal adherence to iron-folic acid intake was assessed using a five-item Medical Adherence Rating Scale (MARS-5). Questions like forgetfulness, altered the dose, stopped medication for a while, miss out on a dose was asked. All items of MARS-5 answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from never to always) with the overall score range between 5 and 25. Participants with lower scores were considered to have low adherence to IFA tablets [Citation20].

Study procedure

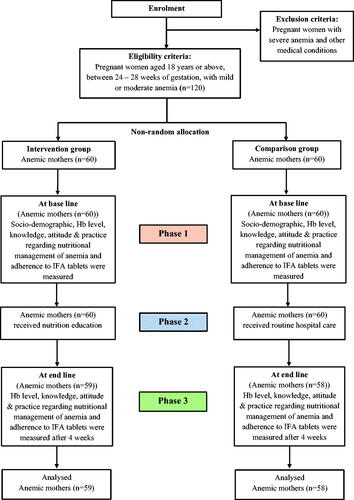

The study was conducted in three phases. The process of conduct of the study is given in .

Phase 1

This phase included the collection of baseline data about demographic and obstetrical variables and hemoglobin values of the anemic pregnant women. The pretest was conducted in both groups to assess the knowledge, attitude, practice regarding nutritional management of anemia and adherence for iron-folic acid intake.

Phase 2

In this phase, a video-assisted individual nutrition education was delivered by the principal investigator immediately after the baseline. Individual nutrient education session was lasting approximately 30 min with the use of laptop. At the end of session, leaflet was given to the pregnant women in the intervention group in addition to the routine hospital care. Further, an SMS alert was sent twice a day for four weeks as reinforcement of regular intake of iron-rich foods and IFA tablets in the intervention group. Routine hospital care only was given to the pregnant women in the comparison group.

Phase 3

End line data were collected after 4 weeks of phase 2. Maternal knowledge, attitude, practice, IFAS adherence, and hemoglobin values were measured in both intervention and comparison groups.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 software for Windows. A Chi-square test was used to compare the baselines of socio-demographics and pregnancy characteristics between the intervention and comparison groups. Baseline differences in the intervention and comparison groups and post-intervention differences in the intervention and comparison groups for maternal nutritional knowledge, attitude, practice, IFAS adherence, and hemoglobin values were compared by using Unpaired t-test. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the present study, 59 pregnant women received video-assisted nutrition education as well as SMS alert for reinforcement of regular intake of iron-rich foods and IFA tablets in addition to the routine hospital care, while 58 pregnant women received routine hospital care only. Three participants could not be followed up during the study (). There was no significant difference between the intervention and comparison groups regarding age, educational level, income level, pre-pregnancy body weight, and gravidity ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic and pregnancy characteristics of study participants represented as percentages.

The majority of pregnant women in the intervention group 49 (83%) and the comparison group 52 (89.7%) had mild anemia at baseline. 21 (35.6%) of pregnant women in the intervention group and 06 (10.3%) in the comparison group had a normal level of hemoglobin after four weeks of intervention. There was a significant improvement in the hemoglobin level of anemic pregnant women in the intervention group compared to the comparison group at the end line ().

Table 2. Comparison of the baseline and end line Hb level in intervention and comparison group.

Before the intervention, only 08 (13.6%) of pregnant women in the intervention group and 09 (15.5%) of pregnant women in the comparison group had good nutritional knowledge scores (knowledge score >20). After the intervention, 32 (54.2%) of pregnant women in the intervention group had a good nutritional knowledge score compared to 15 (25.8%) of pregnant women in the comparison group. Moreover, only a few pregnant women had a negative attitude toward nutritional management of anemia in both intervention and comparison groups at the baseline (05 (8.4% and 04 (6.9%)), respectively). Further, only 09 (15.3%) of pregnant women in the intervention group and 08 (13.7%) of pregnant women in the comparison group had good maternal practice scores at the baseline (practice score >10). After the intervention, 35 (59.3%) of pregnant women in the intervention group had a good practice score compared to 10 (17.2%) of pregnant women in the comparison group. There was a significant difference in the knowledge, attitude, and practice scores regarding nutritional management of anemia in the intervention group compared to the comparison group at the end line ().

Table 3. Comparison of maternal knowledge, attitude and practice scores in intervention and comparison group.

This study found that a majority of pregnant women in both intervention and comparison groups had good adherence to IFA tablets at baseline (51 (86.4%) and 48 (82.7%), respectively). After the intervention, 56 (94.9%) of pregnant women in the intervention group had good adherence compared to 51 (87.9%) of pregnant women in the comparison group. There was a significant difference in the MARS −5 score in the intervention group compared to the comparison group at the end line (). Further, pregnant women in both groups scored lower marks for an item related to forgetfulness to take IFA tablets compared to the other items of the scale ().

Table 4. Comparison of base line and end line and maternal adherence to IFA tablets using Medical Adherence Rating Scale (MARS-5) in intervention and comparison group.

Discussion

The prevalence of anemia among Indian pregnant women is stagnant in the past decade despite the improvement in the IFA adherence during antenatal period from 30.3 to 44.1% [Citation7,Citation8]. Besides adherence with IFA tablets, nutritional and environmental factors should be considered in the prevention or management of anemia during pregnancy [Citation9,Citation10]. The present study was planned to evaluate the effect of nutrition education on nutritional knowledge, attitude, practices, adherence to Iron-folic acid intake, and hemoglobin levels among anemic South Indian pregnant women. The results of the present study showed that pregnant women who received nutrition education through video and leaflets had a significant improvement in knowledge, attitude, practice, adherence to iron-folic acid intake, and hemoglobin levels.

At the end-line, there was a significant improvement in the hemoglobin levels of the intervention group compared to the comparison group (). 21 (35.6%) of pregnant women in the intervention group and 06 (10.3%) in the comparison group had a normal level of hemoglobin after four weeks of intervention. Similarly, a study on Indian pregnant women reported that individual counseling was found to improve hemoglobin levels [Citation21]. Studies reported that nutrition education regarding iron-rich food consumption was significantly improved the hemoglobin levels among Nepalese and Ghana anemic pregnant women [Citation12, Citation22]. Further, nutrition education on nutritional iron supplementation was positively associated with improved hemoglobin levels in pregnant women [Citation22]. Individual education through an anemia pictorial handbook and counseling had shown improvement in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels among Indonesian anemic pregnant women [Citation13]. A quasi-experimental study showed a positive relationship between dietary practices and improvement of hemoglobin levels of pregnant women [Citation23]. In contrast, a randomized control trial reported that no significant effect of nutrition education and counseling on hemoglobin level in a population that is not nutritionally at risk [Citation24]. However, Indian women are more vulnerable to micronutrient deficiency including iron deficiency anemia.

Studies reported that Indian pregnant women had poor knowledge on iron-rich food items and their relationship with the anemic status [Citation14]. Studies revealed the necessity of educational programs to enhance nutritional knowledge and sensitization of women to achieve positive body iron status [Citation25]. The present study showed that the nutrition education intervention was significantly associated with an increase in maternal nutritional knowledge score, attitude score, and practice score regarding nutritional management of anemia in the intervention group compared to the comparison group (). A similar study conducted on Nepalese pregnant women exhibited an improved knowledge score after the nutrition education and iron-rich food-based diet plan [Citation12]. Further, integrated pictorial handbook education and counseling had significantly improved the knowledge score on Indonesian pregnant women at the end of the intervention period [Citation13]. The study done at the University of Ghana stated that health education on anemia during the antenatal visits was significantly increased the knowledge scores in the intervention group [Citation22]. A study reported that nutrition education and specific dietary practices were significantly increased the knowledge of pregnant women on nutrition during pregnancy [Citation26]. Another study reported that 78% of pregnant women had attained a good nutritional knowledge score after nutrition education [Citation27]. Mostly health education and counseling done during antenatal visits tend to be general in the context of India. The health care providers such as accredited social health activist, auxiliary nurse midwife, and lady health visitor are involved in health education and counseling for antenatal and postnatal women in India. They perform various health education and counseling programmes about care during pregnancy, preparation for child birth, breast feeding and new-born services at maternity hospitals/home visits/community settings [Citation28].

The findings of the present study show that nutrition education during antenatal visits could improve maternal knowledge, attitude and practices regarding the nutritional management of anemia. It could help to prevent and manage anemia during pregnancy. Similarly, an interventional study reported that nutrition education sessions were found helpful to prevent anemia by improving the nutritional knowledge score in pregnant women [Citation29].

The NFHS − 4 reported that only 30.3% of pregnant Indian women took IFAS for ≥100 days [Citation7]. Recently NFHS-5 (2019–2021) reported a IFA adherence of 44.1% [Citation8]. However, adherence with IFA tablets is still low in pregnant women in India. The present study found that a majority of pregnant women in both intervention and comparison groups had good adherence to IFA tablets at baseline (51 (86.4%) and 48 (82.7%) respectively). Further, we used the MARS-5 scale to assess the behaviour-related factors of maternal adherence to iron-folic acid intake. The present study showed that the baseline score of the item related to forgetfulness was lower when compared to the other items of the MARS-5 scale in both groups (). Studies reported that forgetfulness is one of the main causes for non-adherence to IFA tablets [Citation30]. In addition to nutrition education, we sent an SMS alert twice a day for four weeks period in the intervention group to the reinforcement of regular intake of iron-rich foods and IFA tablets. We found significant improvement in the adherence to IFA tablets at the end line (56 (94.9%) and 51 (87.9%) respectively). Similar results were reported by other studies conducted with the nutrition education session, individual counseling, and anemic pictorial handbook education [Citation12,Citation13].

The present study has some limitations. Participants were allocated to either the comparison or intervention group purposively. So, there was chance of bias due to lack of randomization.

Knowledge, attitude, practice and adherence to IFA intake were measured by questionnaire-based assessments and subjective self-reports, which are subject to the record biases and socially desirable answer biases. No data were collected on the frequency of iron-rich food intake during the intervention period. Markers of iron status such as serum ferritin, serum iron, and transferrin saturation were not measured due to technical reasons.

Conclusion

Provision of individual nutrition education through video and leaflets was significantly associated with improved nutritional knowledge, attitude, practice scores, adherence to IFA intake and Hb levels. We also recommend that further studies assess the effect of nutrition education from the first trimester of pregnancy and compare it with the pregnancy outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Katherine Thompson, Clinical Social Worker/Psychotherapist for her consent to use the MARS-5 scale in the study. We thank the study participants for their full cooperation during the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO | Global anaemia prevalence and number of individuals affected [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/vmnis/anaemia/prevalence/summary/anaemia_data_status_t2/en/.

- Kalaivani K, Ramachandran P. Time trends in prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(3):268–277.

- WHO | Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; [cited 2021 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin/en/.

- Tandon R, Jain A, Malhotra P. Management of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy in India. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2018;34(2):204–215.

- Rai RK, Fawzi WW, Barik A, et al. The burden of iron-deficiency anaemia among women in India: how have iron and folic acid interventions fared? WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7(1):18–23.

- Kapil U, Bhadoria AS. National iron-plus initiative guidelines for control of iron deficiency anaemia in India, 2013. Natl Med J India. 2014;27(1):27–29.

- International Institute of Population Sciences. India fact sheet national family health survey-4 2015–2016. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- International Institute of Population Sciences. India fact sheet national family health survey-5 2019–2021. Mumbai: IIPS; 2012.

- Samuel TM, Thomas T, Finkelstein J, et al. Correlates of anaemia in pregnant urban South indian women: a possible role of dietary intake of nutrients that inhibit iron absorption. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(2):316–324.

- Varghese JS, Swaminathan S, Kurpad AV, et al. Demand and supply factors of iron-folic acid supplementation and its association with anaemia in North Indian pregnant women. PLOS One. 2019;14(1):e0210634.

- Paknahad Z, Fallah A, Moravejolahkami AR. Maternal dietary patterns and their association with pregnancy outcomes. Clin Nutr Res. 2019;8(1):64–73.

- Sunuwar DR, Sangroula RK, Shakya NS, et al. Effect of nutrition education on hemoglobin level in pregnant women: a quasi-experimental study. PLOS One. 2019;14(3):e0213982.

- Nahrisah P, Somrongthong R, Viriyautsahakul N, et al. Effect of integrated pictorial handbook education and counseling on improving anaemia status, knowledge, food intake, and iron tablet adherence among anemic pregnant women in Indonesia: a quasi-experimental study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:43–52.

- Kulkarni KK. KAP studies among indian antenatal women: can We reduce the incidence of anaemia? J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2015;65(5):320–322.

- International Institute of Population Sciences. National family health survey‑4. 2015‑2016 state fact sheet Puducherry. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary guidelines for Indians manual‑ a manual. India: National Institute of Nutrition, ICMR; 2011.

- Anemia Mukt Bharat, Operational guidelines, Intensified National Iron Plus Initiative, released on April 2018 by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GOI. Available from: http://www.aadivasiaarogyam.com/wpcontent/uploads/2018/06/PoshanAbhiyan-NHM.pdf.

- Chakma T, Vinay Rao P, Meshram PK. Factors associated with high adherence/feasibility during iron and folic acid supplementation in a tribal area of Madhya Pradesh, India. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(2):377–380.

- Kamau MW, Mirie W, Kimani S. Adherence with iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) and associated factors among pregnant women: results from a cross-sectional study in Kiambu county, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):580.

- Chan AHY, Horne R, Hankins M, et al. The medication adherence report scale: a measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(7):1281–1288.

- Garg A, Kashyap S. Effect of counseling on nutritional status during pregnancy. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(8):687–692.

- Otoo G, Adam Y. Effect of nutrition education with an emphasis on consumption of Iron-Rich foods on hemoglobin levels of pregnant women in Ghana. FASEB J. 2016;30(S1):410.2–410.2.

- Al-Tell M, El-Guidi F, Soliman N. Effect of nutritional intervention on anemic pregnant women’s health using health promotion model. Med J Cairo Univ. 2010;78:109–118.

- Kafatos AG, Vlachonikolis IG, Codrington CA. Nutrition during pregnancy: the effects of an educational intervention program in Greece. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50(5):970–979.

- Da Silva Lopes K, Takemoto Y, Garcia‐Casal MN, et al. Nutrition‐specific interventions for preventing and controlling anaemia throughout the life cycle: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(8):CD013092.

- Teweldemedhin LG, Amanuel HG, Berhe SA, et al. Effect of nutrition education by health professionals on pregnancy-specific nutrition knowledge and healthy dietary practice among pregnant women in Asmara, Eritrea: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2021;4(1):181–194.

- Elhameed HA, Mohammed AI, Hameed L. Effect of nutritional educational guideline among pregnant women with iron deficiency anaemia at rural area in Kalyobia governorate. Life Sci J. 9(2):1212–1217.

- Nguyen PH, Kachwaha S, Tran LM, et al. Strengthening nutrition interventions in antenatal care services affects dietary intake, micronutrient intake, gestational weight gain, and breastfeeding in uttar pradesh, India: results of a Cluster-Randomized program evaluation. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2282–2295.

- Nimbalkar PB, Patel JN, Thakor N, et al. Impact of educational intervention regarding anaemia and its preventive measures among pregnant women: an interventional study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(12):5317–5321.

- Lavanya P, Jayalakshmy R, Rajaa S, et al. Adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation among antenatal pregnant women attending a tertiary care center, Puducherry: a mixed-methods study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(10):5205–5211.