Abstract

Objective

Women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), especially those with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, are more likely to develop hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease later in life. However, the risk of lifestyle-related diseases in the immediate postpartum period among Japanese women with preexisting HDP is unclear, and a follow-up system for women with preexisting HDP has not been established in Japan. The purpose of this study was to examine the risk factors for lifestyle-related diseases in Japanese women in the immediate postpartum period and the usefulness of HDP follow-up outpatient clinics based on the situation of the HDP follow-up outpatient clinic at our hospital.

Method

We included 155 women with a history of HDP who visited our outpatient clinic between April 2014 and February 2020. We examined the reasons for dropout during the follow-up period. We also examined the number of new cases of lifestyle-related diseases and compared Body Mass Index(BMI), blood pressure values, and blood and urine test results at 1 and 3 years postpartum in 92 women who had been continuously followed for more than 3 years postpartum.

Results

The average age of our patient cohort was 34.8 ± 4.5 years. A total of 155 women with previous HDP were continuously followed for more than 1 year, of whom 23 had new pregnancies, and eight had recurrent HDP (recurrence rate 34.8%). Of the 132 patients who were not newly pregnant, 28 dropped out during follow-up, the most common reason being that the patient did not show up. The patients in this study developed hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia within a short period. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were at normal high levels at 1-year postpartum, and BMI significantly increased at 3 years postpartum. Blood tests revealed significant deterioration in creatinine (Cre), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γGTP) levels.

Conclusion

In this study, women with preexisting HDP were found to have developed hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia several years postpartum. We also found a significant increase in BMI and worsening of Cre, eGFR, and γGTP levels at 1 and 3 years postpartum. Although the 3-year follow-up rate at our hospital was relatively good (78.8%), some women discontinued follow-up due to self-interruption or relocation, suggesting the need to establish a nationwide follow-up system.

Introduction

Several epidemiological studies have indicated that women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), especially those with gestational hypertension (GH) and preeclampsia (PE), are more likely to develop hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease later in life [Citation1–9].

Although the details of these mechanisms are unclear, it has been suggested that risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) are identifiable when studying the metabolic syndrome of pregnancy [Citation10]. It has been reported that regular follow-up and lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining an optimal body mass index, healthy diet, and exercise habits for women with a history of HDP, may reduce the risk of having CVD in the future [Citation1]. However, few studies have reported the risk of lifestyle-related diseases among Japanese women with preexisting HDP in the immediate postpartum period.

The Aomori prefecture, where our hospital is located, is a rural prefecture in the northeastern part of Japan. It is known as the prefecture with the shortest life expectancy in Japan, with three out of four people dying from lifestyle-related diseases. To improve this situation, we launched an HDP follow-up outpatient clinic in 2014 to provide long-term follow-up care to women with HDP. We named this the HDP-PPAP study (HDP-Postpartum in Aomori prefecture study).

The purpose of this study was to examine the risk factors for lifestyle-related diseases in Japanese women in the immediate postpartum period and the usefulness of HDP follow-up outpatient clinics based on the situation of the HDP follow-up outpatient clinic at our hospital.

Materials and methods

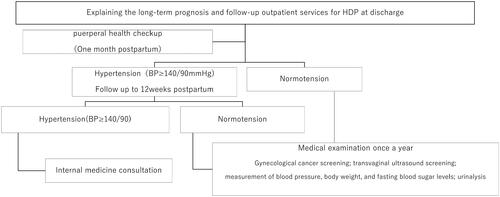

The setup of our follow-up outpatient clinic system is shown in . Our hospital is a university hospital located in northern Japan, Aomori prefecture, that functions as a perinatal, maternal, and child care center, handling high-risk pregnancies. There are 18 obstetricians and gynecologists on staff, as well as a cardiologist and a dietitian. Follow-up outpatient services are provided by an obstetrician or gynecologist who has received training on the treatment of lifestyle-related diseases in pregnancy. Referrals are made to internal medicine specialists.

The names of the patients with HDP were included in a list. Even if a patient was normotensive at the 1-month postpartum health checkup, she was asked to schedule a follow-up outpatient visit annually around her child’s birthday. During the subsequent appointments, the patient’s blood pressure and weight were measured, blood samples were taken, and dietary guidance was provided. In follow-up outpatient services, lifestyle guidance, including weight loss counseling, encouragement of exercise, home weighing, and blood pressure measurement, was provided by an obstetrician or gynecologist using pamphlets. Nutritional guidance was provided by a dietitian. Patients were sent an appointment confirmation card 1 month before their appointment date to avoid dropouts and no-shows.

The patients included in this study were 155 women with a history of HDP who visited our outpatient clinic between April 2014 and February 2020.

We examined the following:

Assessed the reasons for dropout during the follow-up period.

Examined the following items in 92 patients who had been continuously followed for more than 3 years:

the number of new hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease cases.

comparison of blood pressure, BMI (body mass index), and blood and urine test results at 1 and 3 years postpartum.

We diagnosed HDP according to the Japan Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification [Citation11]. If the patient did not visit the follow-up outpatient clinic, we called the patient to confirm if she had relocated or needed to reschedule her visit due to an interruption. A patient who could not be reached by phone was included in the self-interruption category. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure >140/90 mmHg or the use of anti-hypertensive drugs at the time of study participation. Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level >140 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level 150 mg/dL, or if the patient was on lipid-lowering drug therapy. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed based on fasting blood glucose level >126 mg/dL and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level >6.5%, or if the patient was on anti-diabetic medication. All blood samples were collected in the early morning after an overnight fast.

This study has been reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval number: 2021-031). We obtained research consent in an opt-out format.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the 1 and 3-year postpartum groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test as appropriate. A P level < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 155 women with previous HDP were continuously followed for more than 1 year, of whom 23 had new pregnancies, and eight had recurrent HDP (recurrence rate 34.8%).

Of the 132 women who were not newly pregnant, 28 dropped out of the follow-up group. The most common reason for dropping out was self-interruption, followed by relocation and referral to a physician. The follow-up retention rate was 78.8%, with 92 patients followed continuously for more than 3 years.

shows the background of the patients during pregnancy who were followed continuously for more than 3 years: HDP typing was PE in 29 patients, GH in 51 patients, chronic hypertension (CH) in nine patients, and superimposed preeclampsia (SPE) in three patients, with five patients having early onset type.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study population.

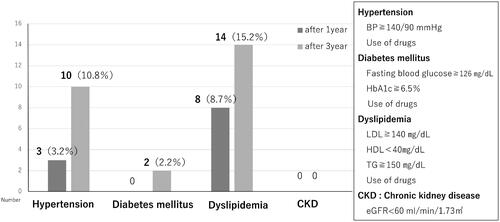

shows the new onset of lifestyle-related diseases at 1 and 3 years postpartum. Hypertension and dyslipidemia were observed after only 1 year.

shows a comparison of blood pressure levels, BMI, and blood and urine test results at 1 and 3 years postpartum. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were at normal high levels at 1 year postpartum, and there was a significant increase in BMI at 3 years postpartum. Blood tests revealed significant deterioration in creatinine (Cre), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γGTP) levels. In particular, eGFR significantly worsened in PE and GH when compared by disease type.

Table 2. Comparison of blood pressure levels, BMI, and blood and urine test results at 1 and 3 years postpartum.

Discussion

This study revealed the risk of lifestyle-related diseases in the early postpartum period in Japanese women with preexisting HDP and problems in our follow-up outpatient clinic.

Women with preexisting HDP developed lifestyle-related disease only 1-3 years postpartum, and both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were already at normal high levels at 1 year postpartum. There was also a significant increase in BMI and worsening Cre, eGFR, and γGTP levels in these patients. Even with this annual follow-up, disease onset and deterioration of data were observed. This implied that some patients developed these diseases despite outpatient follow-up and lifestyle counseling. However, BMI could be improved by lifestyle modification, including exercise therapy, and diet, thus appropriate intervention during follow-up outpatient visits was considered possible. Thus, it is important to not only provide lifestyle counseling but also to encourage patients to improve their lifestyles.

Previous studies have shown that women who develop HDP have an increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) later in life [Citation6,Citation12,Citation13].

In this study, we observed a significant decrease in eGFR in Japanese women with preexisting HDP over a period of only 3 years. eGFR was initially in the normal range, but since it is likely to deteriorate asymptomatically without the patient’s knowledge, regular checkups may contribute to the early detection of diseases such as CKD.

However, it was considered difficult to reduce the risk of developing CVD itself, and intervention in a way that would postpone the onset of CVD and contribute to extending healthy life expectancy was considered necessary.

The problems with the HDP follow-up outpatient clinic observed in this study were that patients with a history of HDP were usually asymptomatic and had little awareness of their disease and that some patients self-interrupted. To reduce the number of dropouts, each patient was mailed an appointment card 1 month prior to the follow-up visit, and uterine and ovarian cancer screening was performed simultaneously for those who wanted it. Despite these incentives, 28 patients (21.2%) discontinued their visits and did not come to the clinic. Therefore, we felt it was necessary to fully explain to patients and their families the risk of CVD after HDP onset and the importance of follow-up in Japan.

There are other reasons why it is difficult to follow up with women with HDP. There is a unique Japanese culture of homecoming births, in which many pregnant women give birth at their parents’ home and move out a few months after childbirth. In this study, 10 women (36%) interrupted follow-up examinations due to relocation. Thus, it may be necessary to create a system that allows access to information about the time of delivery so that follow-up can be done uniformly, even in a new location.

This study had two limitations that need to be acknowledged. The first is the small number of patients included in the analysis and the short follow-up duration. The second is the lack of comparison between the intervention group and a nonintervention group. Given that it is difficult to compare the intervention group with a nonintervention group, examining the risk of developing CVD using studies with long-term follow-up periods is necessary. Future studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are necessary to corroborate the findings of this study.

Conclusion

In this study, women with preexisting HDP were found to have already developed hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia several years postpartum. We also observed a significant increase in BMI and worsening of Cre, eGFR, and γGTP at 1 and 3 years postpartum.

Although the 3-year follow-up rate at our hospital was relatively good (78.8%), some women discontinued follow-up due to self-interruption or relocation, suggesting the need to establish a follow-up system in Japan.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Berks D, Hoedjes M, Raat H, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease after preeclampsia and the effect of lifestyle interventions: a literature-based study. BJOG. 2013;120(8):924–931.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after preeclampsia: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323(7323):1213–1217.

- Kurabayashi T, Mizunuma H, Kubota T, et al. Pregnancy-induced hypertension is associated with maternal history and a risk of cardiovascular disease in later life: Japanese cross-sectional study. Maturitas. 2013;75(3):227–231.

- Watanabe K, Kimura C, Iwasaki A, et al. Pregnancy-induced hypertension is associated with an increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Japanese women. Menopause. 2015;22(6):656–659.

- Mito A, Arata N, Qiu D, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a strong risk factor for subsequent hypertension 5 years after delivery. Hypertens Res. 2018;41(2):141–146.

- Oishi M, Iino K, Tanaka K, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy increase the risk for chronic kidney disease: a population-based retrospective study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39(4):361–365.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):974.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with preeclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(1):1–19.

- McDonald SD, Han Z, Walsh MW, et al. Kidney disease after preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(6):1026–1039.

- Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ. 2002;325(7356):157–160.

- Makino S, Takeda J, Takeda S, et al. New definition and classification of "hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP). Hypertens Res Pregnancy. 2019;7(1):1–5.

- Barrett PM, McCarthy FP, Evans M, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and the risk of chronic kidney disease: a swedish registry-based cohort study. PLOS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003255.

- Paauw ND, van der Graaf AM, Bozoglan R, et al. Kidney function after a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(5):619–626.