?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Introduction

Although the timing of antenatal care has a high potential of reducing maternal and child health problems and can be improved through different mass media exposure, it has been overlooked and remained a major life-costing delinquent issue. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify the relationship between mass media exposure and ANC for further insight.

Methods

We used the 2016 Ethiopian Health and Demography (EDHS) data. EDHS is a community-based cross-sectional survey that applies a two-stage stratified cluster sampling and it is a country-representative. We included 4740 reproductive-age women with complete records in EDHS dataset in this study. We excluded records with missing data from the analysis. We used ordinal logistic regression followed by generalized ordinal logistic to examine mass media relationships with timely antenatal care (ANC). We presented data using numbers, mean, standard deviations, percent or proportions, coefficient of regression, and 95% confidence interval. All analyses were performed using STATA version 15.

Result

We examined the data of 4740 participants for the history of timely initiation of ANC and found 32.69% (95% CI = 31.34, 34.03) timely ANC. Factors such as watching television (TV) less than once a week [coef. = −0.72, CI: −1.04, −0.38], watching TV at least once a week [coef. = −0.60, CI: −0.84, −0.36], listening to radio [coef. = −0.38, CI: −0.84, −0.25], and use internet every day[coef. = −1.37, CI: −2.65, −0.09], are associated with the timely ANC.

Conclusion

Despite its association with improving the timing of ANC, our findings showed mothers need additional support on the use of the media and the timing of ANC. In addition to the mass media, other covariates such as educational status, family size, and husband’s desire affected the timely ANC imitation. These need attention during implementation to avert the current. This is also an essential input for policy and decision-makers.

Introduction

According to the 2005 World Health Organization (WHO) Antenatal Care (ANC) guidelines, initiation of ANC as early as in the first trimester is recommended to promote early identification of health problems of mothers and fetuses [Citation1]. Mothers are anticipated to receive eight sessions of appointments for ANC at clinics or homes [Citation2]. Early identification of pregnancy-related complications enhances early planning, especially in areas where advanced services such as a cesarean section, instrumental delivery, an intensive care unit, an incubator, and oxygen are not available. However, evidence shows that mothers in low and middle-income countries do not have the opportunity to schedule ANC at an early stage of their pregnancy and get the difficulty adhering to an early schedule [Citation3–7].

There is evidence indicating that exposure to mass media is deemed to increase mothers’ awareness to initiate ANC within WHO-recommended time [Citation8]. Radio and Television(TV) exposure also motivate mothers to have an on-time ANC [Citation9,Citation10]. Some evidence has also connected TV with positive commencement to timely initiation of ANC [Citation4,Citation10]. Additionally, when more women are educated and able to read newspapers or other information containing materials, they utilize early ANC [Citation11]. Overall, access to media has a positive effect on ANC and maternal and child health [Citation8,Citation10–12].

According to the Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS) 2016 report, around three in four women of childbearing age and nearly two-thirds of women aged 15 to 49 had no exposure to main media sources (TV, radio, and newspaper) at least once a week. Women who reside in urban areas have five times more likely to read a newspaper than rural women. Similarly, six in ten women living in urban settings watch television weekly, while only about 3% of rural women do. Moreover, one-fifth of women who had completed secondary and above education, and only 4% of women who attended primary education read a newspaper at least once a week [Citation13].

Works of literature to date indicate that studies, which measure early ANC, showed poor service-level achievements. This is especially evident in countries such as Papua New Guinea (23%) [Citation3], South Africa (46%) [Citation13], and the Sub-Saharan region (38%) which extend from 14.5% in Mozambique to 68.6% in Liberia [Citation14]. Late ANC initiation is also evident in countries such as Burkina Faso (62.93%) [Citation5], Tanzania (29.1%) [Citation9], and Ethiopia (21.71%) [Citation10]. Evidence shows that exposure to media outlets enables mothers to have optimal access to ANC. Timely initiation of ANC had increased odds of institutional delivery as compared to delayed first ANC visit. Previously conducted research revealed that early initiation of ANC lets healthcare providers to early detect, treat and manage treatable health conditions that women may develop during pregnancy. Whereas, adverse maternal and child health outcomes including low birth weights, preterm births, jaundice, and mortality of mothers and newborns are attributed to late initiation of ANC [Citation15–18].

Antenatal care is one of the services intended to identify a risk that may lead to maternal deaths during delivery. Early ANC helps to identify risk factor as early as possible and provide enough time for planning management [Citation19]. The country has a health sector transformation plan (HSTP) to increase the proportion of women having at least 4 visits to Antenatal Care from 68% to 95% [Citation19]. HSTP I was implemented in 2015 when Millennium Development Goals ended. It then guided the Ethiopian health system until 2020. Since 2020 HSTP II is underway which is going to end in 2025 [Citation19]. The main aim of the plan is to improve maternal and child health. It strictly focused on improving timely antenatal care to reduce maternal mortality. The maternal mortality rate was 412/100,000 live birth in 2015 and the aim is to reduce it to 199 by 2020 which is not successful HSTP II aims to reduce maternal mortality to 279/100,000 live birth by 2025 [Citation20–22]. Antenatal care visit 1 (ANC1) also improved from 62% in 2016–74% in 2019, during the plan implementation, although only 43% of pregnant women had four or more visits. Thus, early ANC is the major implementation strategy for the HSTP I/II.

Literature indicates that modifiable factors are related to the timing of ANC in Africa. This is also evident in Papua New Guinea where early ANC attendance has been associated with the parity and working status of the mother [Citation3]. In Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, and South Africa early ANC has been associated with pregnancy uncertainty, age, parity, pregnancy disclosure, interactions with healthcare workers, particularly messages about the timing of ANC, the cost of ANC, radio, and television, employment, desired pregnancy, and previous miscarriage [Citation9,Citation13,Citation23]. In Ethiopia, access to media, knowledge of time to book ANC, educational status, family wealth index, community women literacy, distance to the health facility, sleep during pregnancy, the standard of living index, unintended pregnancy, and Tetanus Toxoid (TT) immunization have influenced the early initiation of ANC [Citation10,Citation12,Citation24–26]. This shows that many factors are already identified, but mass media information is not readily available.

Although the proportions of late initiation of ANC are higher and factors associated with it were modifiable, the early initiation of ANC remained late in Africa, the Sub-Saharan region, and Ethiopia. Evidence indicates that mass media-based intervention might improve the timing of ANC initiation. However, the relationship between mothers’ exposure to mass media and timely initiation of ANC was not yet studied in the country though there is significant variation in terms of place of residence (urban/rural), geographical regions, and maternal educational status. Furthermore, we used a special type of ordinal logistic regression (gologit2 with autofit) which directly shows the performance of each variable and can able to report their effect level that can be replicated by other studies. Therefore, in the current study, we aim to understand the association of timely initiation of ANC with the information available in mass media and other covariates from the EDHS 2016 dataset to influence further policy decisions in Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

The setting, data source, and study participants

We used cross-sectional data from the fourth country-level EDHS 2016. EDHS has been carried out every 5 years on a country-representative sample of households. The data was collected from the nine regions and two city administrations. Contextually, these regions are categorized as agrarian (Benishangul-Gumuz Amhara, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People (SNNP), Gambela, Oromia, Harari, and Tigray Regions); pastoralists (Afar and Somali); city administrations (Addis Ababa and Dire-Dawa). We retrieved the data from the DHS website: www.dhsprogram.com after it was released by the measure program.

During sampling, the nine regions and two city administrations were stratified into rural and urban to yield 21 strata where enumeration areas (EA) were sampled independently in each stratum. Probability proportional allocation was carried out before selecting the sample as per the size of EA [Citation27]. The average EA size is 181 households; the urban EAs have a smaller size, with an average of 177 households per EA, while the rural EAs have an average of 183 households per EA. The EA size is an adequate size for the primary sampling unit (PSU) with a sample taken of 28 households per EA [Citation28]. Thus, from the existing dataset, we extracted 4470 weighted women aged 15–49 with exposure to all three media at least once a week (radio, TV, or newspaper), and attended ANC for their last birth from a skilled provider from the dataset. The health facility evidence was used to provide a more complete estimate of coverage complementing the household survey data. We excluded records with incomplete data. Socio-demographic characteristics, reproductive healthcare variables, child vaccination, death, and illness were included in the questionnaire. In this analysis, we focused on the relationship between media exposure and the early initiation of ANC in the country.

Variables of the study

Main response variable

The outcome variable was early initiation of ANC as early as within the first trimester of pregnancy and we coded initiating within the first trimester as “early initiation” [Citation1], within 2nd trimester as “late initiation” [Citation2], and within 3rd trimester “very late” [Citation3]. Since the dependent variable categories were organized in decreasing order, the interpretations were based on the reverse category direction [Citation9].

Independent variables definitions

The data collection tool contains information on whether the woman read a newspaper or magazine, listens to the radio, or watches TV almost every day, at least once a week, less than once a week, or not at all. Use of the internet (never, yes, last month, and yes before last 12 months), frequency of using the internet (Not at all, less than or equal to once a week, almost every week), using a mobile phone, and using landline telephone (yes/no) were also included. Other covariates: Age (15–24, 25–34, and 35–49), residence(urban and rural), region(as discussed under the Setting and data source section), parity (less than 4 and above 4), household size(less than six and six), working status (yes and no), marital status(married and not married), educational status(no education, primary, secondary and tertiary), wealth index(poor, middle, rich), household education, sex of household leader (male and female), partner’s education(un-educated, primary, secondary and higher education), and age at first sex [Citation29,Citation30].

Data processing and analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as weighted frequencies, mean, standard deviations, and percentages or proportions. We cleaned the data according to the study criteria using the STATA version 15.0 and then weighted considering sampling weight, primary sampling unit, and strata before analyzing. Since the response variable has more than two categories, we applied ordinary logistic regression followed by generalized ordinal logistic regression. We conducted a bivariate analysis to identify candidate variables for multivariate analysis at a p-value <.20 [Citation31,Citation32]. In current statistical analysis, studies conduct pre-analysis filters to select variables for final models at a p-value <.25 [Citation33] and commonly at p < .20 [Citation34]. Finally, we presented significant variables using the p-value <.05 and analysis coefficients with 95% CI. We employed the variance inflation factor (VIF) and obtained a mean VIF equal to 1.85. This is an acceptable range.

Statistical analysis

Simple and generalized ordinal logistic regression models

Usually, when the response variable has categories of more than two ordered or unordered, binary logistic regression is not the standard modeling approach. The ordinal logistic regression approach holds to examine the relationship between response and explanatory variables for such categories [Citation35]. The most common method is applying the proportional odds model to approximate the odds of being below or at a particular level of the dependent variable. This considers the probability of that event and all events before it. If the relationship between the independent variables and the categories of response variables is violated and the proportional odds assumption is not met, other modeling approaches are employed to model the relationship. We can apply the partial proportional odds model (PPOM) when the proportional odds assumption is violated. Alternatively, the generalized ordered logit model (GOLM) is employed so that the proportionality constant can be completely or partially relaxed for the set of explanatory variables [Citation36]. Now, the continuation ratio logistic model (CRM) matches the likelihood of the response to a given category with the probability of a higher response. The adjacent-categories logit recognizes the ordering of dependent variable categories and determines the logits of each pair [Citation37]. Thus, we employed the partial proportional model using gologit2.

A major strength of gologit2 is that it can also estimate three special cases of the generalized model: the proportional odds/parallel lines model, the partial proportional odds model, and the logistic regression model. Hence, gologit2 can estimate models that are less restrictive than the parallel line’s models which are estimated by ordinal logistic regression (ologit) (whose assumptions are often violated). It is more parsimonious and interpretable than those estimated by a non-ordinal method, such as multinomial logistic regression (i.e. mlogit). The autofit option simplifies the process of identifying partial proportional odds models that fit the data, while the pl (parallel lines) and npl (non-parallel lines) options can be used when users want greater control over the final model specification. We can mathematically express the gologit2 model as follows

M = no of categories in the dependent variables. From this equation the probabilities that Y will each value 1… M can be

Note that when M = 2, the gologit2 equals logistic regress, and when M > 2, the gologit model becomes a series of binary logistic regression [Citation36].

In this study, we conducted two separate analyses, one for mass media variables and the other for combined mass media and other socio-demographic variables. For both analyses, we applied a generalized ordinal logistic regression model. We also applied ordinal logistic regression to check assumption-violating variables followed by generalized ordinal logistic regression and factor variables like option np1 to control these variables. The final partial proportional odds model was applied with autofit lrforce for its simplicity in reflecting each assumption and test [Citation36].

Parameter estimation

After choosing variables from the available evidence, we performed the brant test to check proportional odds fitness and parallel line assumptions. We used maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to estimate the parameters. The ML method yields values of the unknown parameters that match the predicted and observed probability values. The Fisher scoring algorithm helps ML estimates [Citation38]. The higher the log-likelihood(−2LL) values, the lower the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Baye’s Information Criterion (BIC) show the good fit model [Citation39]. However, the overall model fitness is based on −2LL when adding variables to the intercept-only model. We checked McFadden’s pseudo-R-squared statistic to make sure the comparison between the model with variable and without variable using the Wald test [Citation40].

Marginal effects

It is difficult to achieve the average marginal probability effects of predictors on a single level of the dependent variable in ordinal logistic regression. This is usually easier for categorical independent variables unlike for the continuous. The marginal effect for categorical variables shows, how P(Y) changes when they move from one level to the other after adjusting for the other factors in the model. This is how to respond to the “What effect does the predictor have on the likelihood of the event occurring?” [Citation25]. This method (average marginal effect) is used to measure the association and magnitudes between the levels of response variables and explanatory variables [Citation41].

Results

Descriptive statistics

We examined the 4740 mothers’ history of initiation of ANC in the first trimester and found a proportion of 32.69% (95% CI = 31.34, 34.03). A large proportion of mothers (89.96%) cannot read magazines/newspapers because of illiteracy and 66.22% have no radio access, while 74.70% do not access television. Additionally, mothers in this study do not use internet services (97.93%). Nearly, no significant number of mothers was found using the internet from our analysis (97.44%). Furthermore, 61.20% of mothers do not have a mobile phone to exchange important information. More than half of the mothers (56.85%) practiced late ANC. The age ranges of mothers who participated in this study were 20–24 (20.55%), 25–29 (30.60%), and 30–34 (21.89%). Half (53.90%) of the mothers were not educated. The average number of children per woman was 2–4 (43.95%). Half of the mothers (52.57%) do not have work during data collection and 36.25% of them are in the poor economic status category ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers in the study in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016.

Note that, the model we used is ordinal with three categories (early, late, and very late initiation of ANC). We presented all interpretations as early versus late or very late ANC initiation. Early ANC is the reference, so we interpreted late or very late ANC. Thus, both tables have two parts presenting each variable for both late and very late ANC. Variables, which do not violate the proportional odds model assumption, have similar association statistics under both the late and very late part of the tables. Therefore, we presented only the first part of the table, which is the “very late” initiation of ANC. The cut parts of and (late initiation of ANC) are included as supplementary files ( and ).

Table 2. The relationship between early ANC initiation and mass media.

Table 3. The association of mass media and socio-demographic factors on early ANC, EDHS 2016.

Relationship between mass media and timing of ANC

While watching TV is associated with early ANC initiation, women who watch television (TV) at least once a week have better early initiation of ANC than those who watch less than once a week (64% vs. 41%) with coefficients [coef. = 0.64, 95%CI: 0.46, 0.82] and [coef. = 0.41, 95%CI: −0.21, 0.61] respectively on all-other-things equal basis. Mothers who used the internet almost every day similarly showed better initiation of early ANC than those who used less than or equal to once a week [coef. = 1.46, 95%CI: 0.82, 2.10] and [coef. = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.08, 0.84]. Similarly, on all other things equal basis; women who own mobile have positive initiation of early ANC [coef. = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.44, 0.74] ( and Supplementary file 1).

Other factors affecting timing of ANC

Late or very late initiation of ANC has been affected by increased birth order. On all other things equal basis, mothers with birth order of greater than or equal to four (≥4) have worse early ANC than those with birth order of 2–3 with [coef. = −0.64, 95% CI: −0.97, −0.30] and [coef. = −0.62, 95% CI: −1.00, −0.24] coefficients respectively. On all other things equal basis, women whose husband want fewer children tend to report very late or late ANC [coef. = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.35, −0.06]. On all other things equal basis, a woman with more children is less likely to attend early ANC. early ANC is worse for women with 5–8 children than for 2–4 children women (38% vs 54%) with [coef. = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.7] and [coef. = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.2, 0.88] coefficients respectively. On all other things equal basis, women with higher education reports more early ANC than secondary and primary education (39%, 35%, and 17%) with [coef. = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.73], [coef. = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.1, 0.60], and [coef. = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.33] coefficients respectively ( and Supplementary file 2).

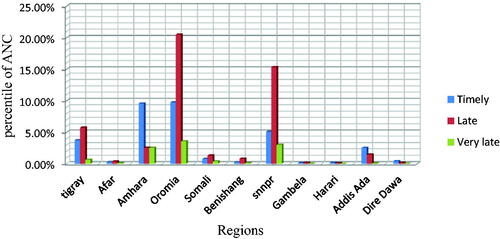

From the figure below, we understand that the timely initiation of ANC ranged from 0.14% in Gambella to 9.74% in the Oromia region. Accordingly, Tigray (3.75%), Amhara (9.56%), South Nation and Nationalities People (5.09%), and Addis Ababa (2.51%) were the regions that showed relatively good achievements ().

Discussion

According to this analysis, the timely initiation of ANC was only 32.69%. Timely initiation of ANC was 40.9% in Addis Ababa [Citation42], and 46.1% in South Gondar [Citation26]. The average Sub-Saharan timely initiation of ANC is 38.0% [Citation14], which is higher than our finding. Our finding is less than all the evidence mentioned above and it may be due to the less socioeconomic development. Overall, 97.93% of women do not use the internet in our study. The finding is consistent with that of Bangladesh where internet use is also small [Citation43]. A study conducted in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan revealed that the impact of media like the internet is higher on prenatal care; however, mothers do not use the media [Citation44]. In other words, 66.22% of mothers do not have access to the radio. This is less than the finding from a study conducted in Nepal [Citation12]. The discrepancy may be due to the educational status difference between the women in the two countries. Additionally, 74% of mothers have no access to TV. A study conducted in India shows that the use of TV is largely associated with the good initiation of ANC. The poor access to TV and late timing ANC (36.69%) might indicate the poor access to sources of information which also is due to the low awareness. Poor access to the existing source of information is also evidenced by other studies [Citation7–10,Citation12]. However, using mass media has been presented with timely initiation of ANC.

In other words, 53.90% of the women were not educated in Ethiopia. A large-scale study in the Sub-Saharan region showed that maternal education is 33.8% [Citation14] in the region. Another small scales study in Northern Ethiopia showed that 58.3% of women do not have formal education [Citation26,Citation45]. Although education is usually an important factor in improving maternal and child health, it is still inadequate for our study. The reason might be due to sociocultural challenges, which might not improve enough [Citation46].

Among associated factors, women who watch television (TV) report higher timely initiation of ANC. this finding is consistent with other findings [Citation8,Citation12]. This is might show that promoting watching TV for mothers may result in increased use of timely ANC and other services. Furthermore, the mother who uses the internet similarly reports higher initiation of timely ANC this is also supported by other evidence from other studies [Citation8,Citation43,Citation44]. Women who own mobile phones showed better initiation of timely ANC. This shows that although a small proportion of the respondents used the internet and TV, and mobile phones, they are largely ANC users on time than others [Citation6,Citation7,Citation10,Citation47]. This might indicate that using mass media and other media for information dissemination improves maternal services. This is an essential input for policy-makers.

As birth order increased from 23 to greater than or equal to four, the relation with timely ANC initiation worsened. Another study also demonstrated a worse relationship between the increased number of children and timely ANC initiation [Citation48]. This consistency may indicate the importance of birth control for the continuum of maternal care. The husband’s desire to have fewer children increased the probability of late or very late timing of ANC initiation. A study conducted in Southern Ethiopia had consistent findings on the husband’s effect on the use of timely ANC [Citation10]. This might indicate that promoting partner involvement in maternal services is improving it. As the number of children increases, the tendency to timely ANC decreases. This finding is supported by another study in Nepal [Citation49]. Thus, health education and the use of modern contraceptives might be more important for multigravida mothers. All levels of maternal education are associated with the probability of timely ANC service initiation. From other studies, maternal education is also associated with improved use of maternal health services [Citation45,Citation49–51]. However, maternal education remained underachieved in many studies [Citation6,Citation8,Citation10,Citation24,Citation52]. The African Union Agenda 2063 also promotes higher achievement in maternal education because of its underachievement in the continent [Citation53]. The reason might be the access or availability disparities among women because of the resource limitation. Despite its strong findings, this study has some limitations like the secondary nature of data, time lapse between data collection and this analysis, disproportional sampling technique, and hierarchical nature of data. The authors followed international DHS definitions and data analyses, weighted the data, made references back to the time of data collection for educational status, wealth index, and other variables followed generalized ordinal logistic regression which includes hierarchical consideration and avoided over-merging data by the aforementioned method to handle all possible limitations.

Conclusion

Although the timing of antenatal care has multiple folds of benefits in identifying early life costing problems for both mothers and their children, this study identified that many work need to be done to solve the problem. The analyses and overall evidence from the literature showed that mass media factors like the use of the internet, TV, radio, and reading ability are still riding far away from expectation. Other factors like educational status, family size, working status, and husband’s desire for a child overloaded mothers’ timely ANC. Moreover, attention is necessary for multipara mothers as evidence indicates they might ignore service as their experience increases. Comprehensive interventions which are also part of the African Union Agenda 2063 include maternal education and financial capacity, enhancing working opportunities for women, and additionally increasing media exposure opportunities through frequent mobilization are very critical. The information obtained from this study might be important for policy-makers and an essential document for decision-makers.

Ethical approval

This study used secondary data from demographic and health survey data files. Initially, the MEASURE DHS team was formally requested to access the datasets by completing the online request form on their website (www.dhsprogram.com). Accordingly, permission to access the data and the letter of authorization was obtained from ICF international. Therefore, for this study consent to participate is not applicable. We kept all data confidential, and no effort was made to identify households or individuals. The Ethiopian Health Nutrition and Research Institute Review Board (EHNR-IRB) and the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC) at the Ministry of Science and Technology of Ethiopia, approved EDHS 2016. The authors also confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Authors contribution

GG has analyzed the EDHS data while, GG, SH, SS, & BT were equally involved in the conception of the study, interpreted the results, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Measure DHS, ICF International Rockville, Maryland, USA for allowing us to use the 2016 EDHS data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The survey dataset used in this analysis is the third party data from the demographic and health survey website (www.dhsprogram.com) and permission to access the data is granted only for registered DHS data user.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. 2005. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- WHO. Antenatal care guidelines malaria in pregnancy frequently asked questions (FAQ). 2016: p. 1–6.

- Seidu A. Factors associated with early antenatal care attendance among women in Papua New Guinea: a population – based cross – sectional study. Arch Public Health. 2021;79:70.

- Yehualashet DE, Seboka BT, Tesfa GA. Determinants of optimal antenatal care visit among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of Ethiopian mini demographic health survey 2019 data. Reprod Health. 2022;19:61.

- Mgata S, Maluka SO. Factors for late initiation of antenatal care in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–9.

- Annotation T, Author A, Type SA, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with late first antenatal care visit in kaya health district, Burkina. Afr J Reprod Health. 2022;1:1–10.

- Arega A, Amlaku T, Aweke M, et al. Factors associated with timely initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia: sectional study. Nurs Open. 2022;9(2):1210–1217.

- Wang Y, Etowa J, Ghose B, et al. Association between mass media use and maternal healthcare service utilisation in Malawi. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1159–1167.

- Sserwanja Q, Mutisya LM, Musaba MW. Exposure to different types of mass media and timing of antenatal care initiation: insights from the 2016 Uganda demographic and health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:1–8.

- Geta MB, Yallew WW. Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2017;2017:1–6.

- Fisayo T, Akim J. Factors associated with the number of antenatal care visits among internally displaced women in Northern. Afr J Reprod Health. 2022;25(2):1–12.

- Acharya D, Khanal V, Singh JK, et al. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:4–9.

- Muhwava LS, Morojele N, London L. Psychosocial factors associated with early initiation and frequency of antenatal care (ANC) visits in a rural and urban setting in South Africa: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:18.

- Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, Liyew AM, et al. Timely initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLOS One. 2022;17(1):e0262411.

- Aboagye RG, Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, et al. Association between frequency of mass media exposure and maternal health care service utilization among women in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for tailored health communication and education. PLOS One. 2022;17(9):e0275202.

- Atuhaire R, Atuhaire LK, Wamala R, et al. Interrelationships between early antenatal care, health facility delivery and early postnatal care among women in Uganda: a structural equation analysis. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1830463.

- Sserwanja Q, Nabbuye R, Kawuki J. Dimensions of women empowerment on access to antenatal care in Uganda: a further analysis of the Uganda demographic health survey 2016. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(3):1736–1753.

- Tuladhar H, Dhakal N. Impact of antenatal care on maternal and perinatal utcome: a study at Nepal medical college teaching hospital. Nepal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;6(2):37–43.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Ethiopian health sector transformation plan.2015/16 – 2019/20. Fed Democr Repub Ethiop Minist Heal. 2015;20:50.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) and ICF. Mini demographic and health survey 2019: key indicators. Rockville (MD): EPHI and ICF; 2019. p. 35.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019: key indicators. Rockville (MD): EPHI and ICF; 2019.

- FMoH. Ethiopian health sector transformation plan II. Ethiop Minist Health. 2021;25:96.

- Were F, Afrah NA, Chatio S, et al. Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLOS one. 2013;8(1):e53747.

- Hanna G, Yemane B. Timing of first antenatal care visit and its associated factors among pregnant women attending public health facilities in Addis Ababa. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(1):139.

- dewau R, Muche A, Fentaw Z, et al. Time to initiation of antenatal care and its predictors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: cox-gamma shared frailty model. PLOS one. 2021;16(2):e0246349.

- Wolde HF, Tsegaye AT, Sisay MM. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Zemen primary hospital, South Gondar, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):1–8.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville (MD): CSA and ICF; 2016.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019: final report. Rockville (MD): EPHI and ICF; 2021. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey: key indicators. Rockville (MD): EPHI and ICF; 2019.

- Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK, et al. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville (MD): ICF; 2018. p. 81. Available from: https://preview.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSG1/Guide_to_DHS_Statistics_DHS-7_v2.pdf

- Bantie GM, Tamirat KS, Woya AA, et al. Cancers preventive practice and the determinants in Amhara regional state, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS One. 2022;17(5):e0267189.

- Aynalem ZB, Yazew KG, Gebrie MH. Evidence-based practice utilization and associated factors among nurses working in Amhara region referral hospitals, Ethiopia. PLOS One. 2021;16(3):e0248834.

- Mingude AB, Dejene TM. Prevalence and associated factors of gender based violence among baso high school female students, 2020. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):247.

- Heinze G, Wallisch C, Dunkler D. Variable selection – a review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom J. 2018;60(3):431–449.

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. Vol. 37. Boca Raton (FL): CRC press; 1989.

- Williams R. Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. Stata J. 2006;6(1):58–82.

- McCullagh P. Regression models for ordinal data. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1980;42:109–142.

- Soon JJ. The determinants of students’ return intentions: a partial proportional odds model. J Choice Model. 2010;3(2):89–112.

- Washington SP, Karlaftis MG, Mannering F. Statistical and econometric methods for transportation data analysis. Boca Raton (FL): Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2010.

- Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognostic modelling with logistic regression analysis: a comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Stat Med. 2000;19(8):1059–1079.

- Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 2012;12(2):308–331.

- Adela LA, Tiruneh MA. Initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2020;9:248.

- Parvin RA, Alam MF-E, Hossain MB. Role of mass media in using antenatal care services among pregnant women in Bangladesh. Indones J Innov Appl Sci. 2022;2(2):143–149.

- Fatema K, Lariscy JT. Mass media exposure and maternal healthcare utilization in South Asia. SSM Popul Health. 2020;11:100614.

- Wolde F, Mulaw Z, Zena T, et al. Determinants of late initiation for antenatal care follow up: the case of northern Ethiopian pregnant women. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1–7.

- The Bergen Project. The rise and fall of girls’ education in Ethiopia. 10 Facts About Girls Education in Ethiopia, quarter of whom will drop out before graduation. 2018. p. 1–2. Available from: https://borgenproject.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-girls-education-in-ethiopia/#:∼:text=Top.

- Lund S, Nielsen BB, Hemed M, et al. Mobile phones improve antenatal care attendance in Zanzibar: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:29.

- Muzaffar N. Maternal health and social determinants: a study in Jammu And Kashmir. Public Health Res. 2015;5(5):144–152.

- Paudel YR, Jha T, Mehata S. Timing of first antenatal care (ANC) and inequalities in early initiation of ANC in Nepal. Front Public Health. 2017;5:242.

- Agha S, Tappis H. The timing of antenatal care initiation and the content of care in sindh, Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):190.

- Dessie ZG, Zewotir T, Mwambi H, et al. Multilevel ordinal model for CD4 count trends in seroconversion among South Africa women. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–12.

- Alemu Y, Aragaw A. Early initiations of first antenatal care visit and associated factor among mothers who gave birth in the last six months preceding birth in bahir dar zuria woreda North West. Reprod Health. 2018;15:1–8.

- African Union AU commission. A shared strategic framework for inclusive growth and sustainable development: African union agenda 2063. 2013;1–21. Available from: 33126-doc-01_background_note.pdf(au.int).