Abstract

Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) result into severe, life-threatening fetal anemia and cause intrauterine death of the fetus. It is tough for an early diagnosis of FMH before pregnancy and few authors reported FMH in a twin pregnancy. Therefore, we reported a case of massive FMH. The patient felt a decrease in fetal movements at 33+5 gestational weeks. Cardiotocography showed sinusoidal heart rate patterns in one fetus. The fetal hemoglobin level in maternal blood was 6.4% (normal range for single pregnancy, 0.0%–2.0%). Since the patient was diagnosed with fetal distress, cesarean section was performed and both babies delivered to receive neonatal treatment. Severe anemia was apparent in both neonates, based on red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit of 0.75 × 1012/L and 0.61 × 1012/L, 2.8 g/dL and 2.4 g/dL, and 10.0% and 8.4%, respectively. The neonates were admitted to the intensive care unit for prematurity care and presently are well. In our experience, an early diagnosis of FMH contributed to saving fetus. Obstetricians should highlight fetal movements counting to every patient. Once massive FMH occurs in monochorionic twins, both fetuses may develop severe anemia and require emergency intervention.

1. Introduction

Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) is defined as a loss of fetal blood cells to the maternal circulation [Citation1]. Interestingly, transference of fetal blood to the maternal blood system and vice versa is a physiological event that occurs in pregnancy and at birth [Citation2]. The incidence of clinically significant cases is estimated about 0.01%–0.03% of pregnancy women [Citation3]. However, it is suspected that there is high number of cases that remains unreported, as in miscarriages, or intrauterine death of the fetus [Citation4]. In literature, severe FMH has been described as a fetal blood loss of more than 30 mL [Citation5]. Severe FMH can result into severe, life-threatening fetal anemia depending on the amount of blood loss. The diagnosis of FMH is usually made in cases of severe blood loss, with fetuses exhibiting symptoms of decompensation such as abnormal heart rate and/or fetal hydrops.

To early detect FMH and avoid intrauterine death of the fetus, the collection and analysis of FMH are needed. We reported this case of massive FMH in a monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy with chief complaint of a decrease in fetal movements.

2. Case Report

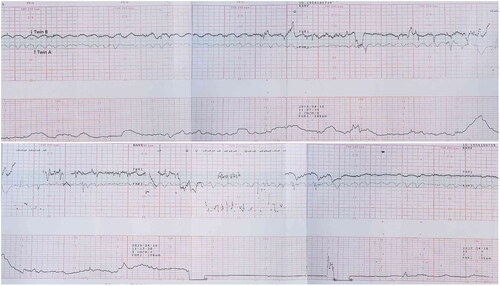

A 27-year-old Chinese woman, gravid 2 para 1, presented at our hospital with a decrease in fetal movements for 1 day. Ultrasonography conducted earlier in the pregnancy had confirmed that she was carrying monochorionic-diamniotic twins. Estimated fetal body weight of both fetuses was 2.225 g and 2027 g. Routine biweekly ultrasound examinations prior to admission revealed normal fetal growth and normal amniotic fluid volume for both fetuses. Cardiotocography showed sinusoidal heart rate patterns in Twin A and nonreactive non-stress test in Twin B (). The middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV) was 118 cm/s and 121 cm/s for both fetuses. Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) titer in maternal blood was 6.4% (normal range for single pregnancy, ≤2.0%). Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in maternal blood was 26736.1 ng/mL (normal range for nonpregnancy women, ≤7 ng/mL). Based on chief complaint, fetal heart rates, maternal HbF titer, and AFP concentration, we diagnosed the mother with massive FMH. Both babies were delivered by cesarean section and received neonatal care. One dose (6 mg) of dexamethasone was used for preterm labor to avoid the risk of lung edema before emergency cesarean section. Twin A was a girl weighing 2050 g, with 1–5–10 min Apgar scores of 2-7-8. Twin B was a girl and weighing 1800 g, with 1–5–10 min Apgar scores of 2-7-8. Blood gas analysis of umbilical arterial blood from both babies showed that pH was 7.26 and 7.32. Both babies showed severe anemia; red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit of 0.75 × 1012/L and 0.61 × 1012/L, 2.8 g/dL and 2.4 g/dL, and 10.0% and 8.4%, respectively. Both babies received tracheal intubation and surfactant administration treatment for respiratory distress syndrome. Although SaO2 was 100% in both babies after treatment for respiratory distress because of prematurity, both babies showed systemic skin pallor. Blood pressure and heart rate of both babies was 55/29 mmHg and 54/30 mmHg and 139 beats/min and 135 beats/min, respectively. Chest radiography showed no cardiomegaly in either fetus. After admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), red cell blood transfusion was started. The total amount of blood transfusion was 80 mL in Twin A and 72 mL in Twin B. After transfusion, hemoglobin concentration for both babies was 13.7 g/dL and 14.2 g/dL, respectively. On the second day after birth, both babies were extubated. After that, the neonatal course was uneventful for both babies. The twins were discharged 13 days and 23 days after birth. As of 3 years, both babies had shown no abnormalities in long-term follow-up physical and neurological examinations. Vascular anastomosis in the monochorionic placenta was not detected by postoperative pathological examination.

3. Discussion

FMH refers to the entry of fetal blood into the maternal circulation before or during delivery [Citation1]. Severe fetal anemia can result and increases the risk of neurologic injury, stillbirth, or neonatal death [Citation6]. In a twin pregnancy, it may be difficult to notice the decreased fetal movements in one fetus due to the movements of the other fetus. But in this patient, acute FMH was identified very quickly as both fetuses showed decreased fetal movements due to severe anemia. Herein, for high-risk pregnancy, obstetricians should highlight fetal movement counting to every patient. Antepartum trauma, amniocentesis, cordocentesis, external version and placental abruption have all been reported as causing FMH [Citation1]. Although intraplacental choriocarcinoma was another reported cause of massive FMH [Citation7], our patient had no placental tumor. Furthermore, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) can also cause severe fetal anemia in twin pregnancies [Citation8]. But in this situation, only one fetus will suffer from anemia. In our case, the amniotic fluid volume of both fetuses was normal and TTTS was ruled out. Both twins exhibited a terrible heart rate pattern, which is usually associated with severe fetal anemia. In addition, we detected an extremely elevated level of HbF, at 6.6%, in the maternal serum. This allowed us to diagnose massive FMH. As a normal amount for FMH is ≤0.2 mL, a large amount of fetal blood had clearly entered the maternal circulation. Simultaneously, maternal AFP was measured, as it is mentioned as a reliable monitoring marker of FMH in literature [Citation9]. Accordingly, AFP was highly elevated (26,736.1 ng/mL in this case).

In recent years, ultrasound examinations have been used to measure fetal MCA-PSV, so that fetal anemia due to FMH might be detected [Citation10]. However, proper estimation of MCA-PSV is difficult in some cases such as twin pregnancies, due to fetal presentation. Besides, when acute FMH was highly suspected, timing of rescue of newborn may be missed if ultrasound was repeated. In such cases, serial fetal heart rate monitoring may effectively detect symptoms of fetal anemia through identification of sinusoidal fetal heart rate patterns. Severe fetal anemia due to massive FMH can be treated in utero for premature fetuses.

When severe FMH is detected in a vital fetus with cardiovascular distress, there are two options of treatment: delivery or prolongation of pregnancy. The latter will include intrauterine blood transfusion (IUT). Lindenburg et al. published in 2014 a review of current indications of IUT. IUT can significantly prolong pregnancy to a mature gestational age and improve fetal outcome [Citation11]. Votino et al. reported a case of FMH which was treated successfully by fetal intravascular transfusions for which MCA-PSV detected fetal anemia [Citation12]. However, other researchers recommended urgent delivery and neonatal treatment rather than IUT for women with massive FMH after 32 gestational weeks [Citation13]. If the pregnancy is near-term, emergency delivery and immediate blood transfusion is the treatment of choice. It is a decision that should be made by experienced obstetricians and neonatologists together with the parents-to-be, considering the pros and cons of treatment options with the goal of minimizing fetal and maternal complications. In addition, as the patient was carrying a twin pregnancy, IUT was considered technically difficult. And the gestational weeks of the patient was 33+5, we therefore chose to deliver the twins and implement subsequent neonatal management.

The finding that the degree of severe anemia in both fetuses was almost equal is very interesting. We speculate that vascular anastomoses of the placenta heavily influenced the development of anemia in both twins. However, no vascular anastomosis in the placenta was detected by postoperative pathological examination. And no signs of TTTS were identified. Even though no evidence was available regarding whether FMH affected both fetuses to the same degree or whether FMH of 1 fetus was equilibrated by interfetal transfusion, we speculate that interfetal transfusion through vascular anastomoses might have caused the comparable levels of anemia in both fetuses. In the case of monochorionic twins, when abnormal circulation occurs in 1 fetus, the other fetus may be harmed by the presence of vascular anastomoses in the placenta.

In conclusion, obstetricians should highlight fetal movements counting to every patient. Once massive FMH occurs in monochorionic twins, both fetuses may develop severe anemia. Therefore, when abnormal circulation is identified in 1 fetus, special attention must be given to the other fetus in the case of monochorionic twins. After delivery, a strong team of neonatologists played a key role for recovery and long term follow up.

Author contributions

Shuying Liao contributed to the protocol development, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Jitong Zhao contributed to protocol development and manuscript writing. Tao Li developed data analysis and manuscript editing. Tao Yi, Xiaojuan Lin, and Ce Bian involoved in manuscript editing. Chen Ling involved in protocol development, manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee on human research at West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 2019047). The patient provided informed consent for the publication of her clinical and imaging data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wylie BJ, D'Alton ME. Fetomaternal hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):1039–1051.

- Sohda S, Samura O, Johnson KL, et al. Limited expression of fas and fas ligand in fetal nucleated erythrocytes isolated from first trimester maternal blood. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22(13):1213–1218.

- Kadooka M, Kato H, Kato A, et al. Effect of neonatal hemoglobin concentration on long-term outcome of infants affected by fetomaternal hemorrhage. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(9):431–434.

- Stroustrup A, Plafkin C, Savitz DA. Impact of physician awareness on diagnosis of fetomaternal hemorrhage. Neonatology. 2014;105(4):250–255.

- Stefanovic V, Paavonen J, Halmesmaki E, et al. Two intrauterine rescue transfusions in treatment of severe fetomaternal hemorrhage in the early third trimester. Clin Case Rep. 2013;1(2):59–62.

- Biankin SA, Arbuckle SM, Graf NS. Autopsy findings in a series of five cases of fetomaternal haemorrhages. Pathology. 2003;35(4):319–324.

- Aso K, Tsukimori K, Yumoto Y, et al. Prenatal findings in a case of massive fetomaternal hemorrhage associated with intraplacental choriocarcinoma. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;25(1):158–162.

- Chon AH, Korst LM, Grubbs BH, et al. Risk factors for fetomaternal bleeding after laser therapy for twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(12):1232–1237.

- Maier JT, Schalinski E, Schneider W, et al. Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH), an update: review of literature and an illustrative case. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292(3):595–602.

- Cosmi E, Rampon M, Saccardi C, et al. Middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity in the diagnosis of fetomaternal hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117(2):128–130.

- Lindenburg IT, van Kamp IL, Oepkes D. Intrauterine blood transfusion: current indications and associated risks. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2014;36(4):263–271.

- Votino C, Mirlesse V, Gourand L, et al. Successful treatment of a severe second trimester fetomaternal hemorrhage by repeated fetal intravascular transfusions. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;24(4):503–505.

- Watanabe N, Jwa SC, Ozawa N, et al. Sinusoidal heart rate patterns as a manifestation of massive fetomaternal hemorrhage in a monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy: a case report. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27(3):168–170.