Abstract

Objectives

To explore the relationship between a history of induced abortion and follow-up preterm birth.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 27,176 women aged 19 to 48 years old in the city of Dongguan. Participants were divided into two groups according to the history of induced abortion. We used log-binomial regression to estimate adjusted risk ratios of preterm birth (gestation at less than 37 weeks) and early preterm birth (gestation at less than 34 weeks) for women with a history of induced abortion. Four models adjusted for different baseline data were used to verify the stability of the results. We also performed a subgroup analysis and mediation effect analysis to control for the influence of confounding factors and analyzed the relationship between the number of abortions and subsequent preterm birth.

Results

Our study included 2,985 women who had undergone a prior induced abortion. Women who reported having a prior induced abortion were more likely to have preterm births before 37 weeks and 34 weeks, with risk ratios of 1.18 (95% CI 1.02–1.36) and 1.65 (95% CI 1.23–2.21), respectively. The above associations were stable in all models. We also found that a history of induced abortion was independently associated with a higher risk of preterm birth and early preterm birth in the subgroups. After controlling for the indirect effect of demographic data, the direct effect of abortion history on follow-up preterm delivery was still significantly different. The higher the number of abortions, the greater the risk of subsequent preterm birth.

Conclusions

This study suggests that induced abortion increases the risk of subsequent preterm birth.

Introduction

Induced abortion has become an important global public health problem and one of the greatest human rights dilemmas [Citation1,Citation2]. The rate of induced abortions in 2010–2014 was 35 per 1000 women [Citation3]. Currently, an estimated nearly 50 million abortions are induced each year [Citation1]. To control the rapid growth of the population, China launched the family planning policy in 1979. As the economy of China grows, a large number of people have poured into cities from rural areas, and people are becoming more open-minded about sex [Citation4]. For these reasons, China accounted for 1/5 of the total number of abortions worldwide [Citation2]. From 1979 to 2010, the average annual induced abortion rate was 29.0% among married women 20–49 years old [Citation5]. In recent years, the number of abortions has been declining, but there are still many abortions every year [Citation5].

China ranks second in the number of preterm births after India [Citation6]. A history of induced abortion may cause some potential short- and long-term risks, including organic diseases, behavioral problems, and diseases in the offspring [Citation7]. Over the years, the relationship between the history of induced abortion and the risk of preterm birth has received attention. However, the conclusions are inconsistent. There is some evidence that women with a history of induced abortion have an increased risk of preterm birth [Citation8–12]. However, some studies did not find an association between previous induced abortion and preterm birth [Citation13–18]. There are few reports focusing on Chinese populations, and the conclusions need to be confirmed [Citation13,Citation15].

As the prevalence of induced abortion is high in China, it is very important to understand the impact of induced abortion on subsequent preterm birth. To further explore the relationship between abortion and subsequent preterm birth, we performed a population-based retrospective cohort study in China to examine the association between a history of induced abortion and the risk of preterm birth.

Materials and methods

Study design and participant

In the materials and methods section, we referred to two articles published before [Citation19,Citation20]. The National Free Preconception Health Examination Project (NFPHEP) was launched by the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission and the Ministry of Finance in 2010 with the aim of providing free health examinations, counseling services, and follow-up of pregnancy outcomes for couples in rural areas who planned to become pregnant within the next 6 months. Dongguan, a coastal city in Guangdong Province, southern China, has implemented the NFPHEP since October 2012. However, in Dongguan, this project serves all couples with household registration, not just rural couples.

The cohort study was based on the NFPHEP of Dongguan. We included couples who participated in the examination from October 2012 to December 2018 and subsequently had at least a live birth as research subjects. The data from their examination before this pregnancy were collected retrospectively. Then, we explored the relationship between a history of induced abortion and the risk of subsequent preterm birth. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Dongguan Maternal and Child Health Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent before the examination.

We excluded subjects without abortion data or gestational period data; with twins or multiple births; with a history of spontaneous abortion; with diabetes, hypertension and other serious chronic diseases; and with genital tract infectious disease or organic diseases of the reproductive system.

Data sources

The implementation steps of the examination were as follows. The staff learned about the list of local newlyweds from the relevant departments and informed them about participating in the NFPHEP 3–6 months before pregnancy at the designated medical institutions. At these medical institutions, doctors collected basic information, behavioral information (smoking, diet, drinking, environmental exposure, etc.), childbearing history (number of births, abortions, birth defects, etc.), and medical histories. The doctors then examined the couples, including routine physical and reproductive system examinations, blood tests, urine test, sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis B virus, blood glucose examinations, and so on. Finally, the doctors evaluated the risk according to the basic information and examination results of the couples and provided them with health guidance and eugenics counseling. All questionnaires were designed in advance by the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission.

After the examination, the staff followed up with the subjects by telephone every three months to confirm whether they had given birth. If a woman gave birth to a live child, the staff collected information on her pregnancy outcome in detail, including delivery date, gestational weeks, birthweight, singleton or multiple births, delivery mode, birth defects, etc. The examination information and pregnancy outcomes were entered into a web-based electronic data collection system called the prepregnancy examination system.

We selected couples with pregnancy outcomes and collected their examination data. Then, we explored the relationship between a history of induced abortion and subsequent premature delivery.

Variables

The variables we collected included the following: demographic information of the couple: age (20–25 years, 26–29 years, 30–34 years, or 35–49 years), body mass index (<18 kg/m2, 18–24 kg/m2,or >24 kg/m2), level of education (primary school or below, junior or senior high school, or college or higher), ethnic origin (Han or others), occupation (primary industry, second industry, tertiary industry or others), and region (suburb or urban district); daily habits and physical condition: smoking(yes or no), passive smoking(yes or no), drinking(yes or no), vegetarian(yes or no), carnivore(yes or no), nutritional anemia(yes or no), hepatitis B (yes or no), occupational radiation exposure (yes or no), EDC exposure (yes or no), and heavymetal exposure (yes or no); childbearing history: contraception (yes or no), primipara (yes or no) and history of abortion(yes or no); gender of the fetus (female or male), and gestation period.

Bias and control

Special funding was provided to ensure that every included woman was followed up. Responsible staff were sent to collect and record the information. The government inspected and examined the prepregnancy examination system every half year at the county level to prevent missing reports. In addition, the Chinese government has established a full set of birth registration systems that record in detail the birth date of each live birth child [Citation21]. Therefore, to prevent loss of follow-up, we checked the prepregnancy examination system with the Dongguan birth registration systems. When there was a discrepancy between the two systems, we checked the information through telephone interviews with the parents.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were preterm birth and early preterm birth. Preterm births were defined as births delivered at gestational ages less than 37 weeks (259 days), and early preterm births were defined as births delivered at gestational ages less than 34 weeks (238 days) [Citation22]. The incidence of preterm births and early preterm births was the number of preterm and early preterm births divided by the total number of singleton live births, respectively.

Statistical method

According to the history of abortion, we divided the participants into two groups: women without a history of induced abortion (control group) and women with a history of induced abortion (exposure group). The baseline characteristics of the participants were described by percentage (%), and the chi-square test was used to compare the distributions of different baseline characteristics between the two groups. In particular, considering the possible influence of fathers and infants, we included the condition of the fathers and infants in the baseline data analysis.

Log-binomial regression models [Citation23] were used to estimate the risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of preterm births for women with a history of induced abortion. Multivariate analysis models were used to adjust for the underlying factors of preterm birth. We set up four multivariable models adjusted for different covariates and compared the four results to evaluate the stability of the results. In Model A, we did not adjust any variables. In Model B, we adjusted the demographic data of women, including age, body mass index, level of education, ethnic origin, occupation, and region. In Model C, based on Model B, we additionally adjusted other significant baseline data of the mothers. In Model D, in addition to the variables included in Model C, we adjusted some factors of the husbands and fetuses.

A subgroup analysis was performed according to the baseline characteristics. Among these baseline subgroups, we examined the associations between induced abortion and preterm birth and early preterm birth after adjusting for other potential risk factors. With a few values missing, mode completer and regression estimation methods were used for interpolation in the numeration data and measurement data, respectively. As a validation of the subgroup analysis, we also used a mediation effect analysis to determine the direct effect of induced abortion on preterm birth after excluding the indirect influence of other factors [Citation24]. Finally, we analyzed the effect of the number of abortions on preterm birth. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance was defined with a two-tailed threshold of 0.05.

Results

Participants

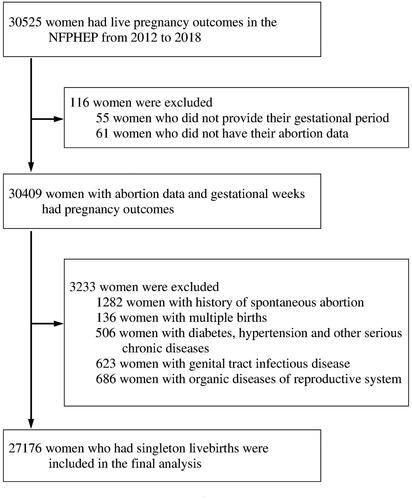

By 1 January 2019, 30,525 women had pregnancy outcomes. A total of 3349 women were excluded, as shown in . The remaining 27,176 women were included in the final analysis. The average age of the women was 29.2 (s.d. 4.442) with a range of 19–48 years, and their husbands averaged 30.1 years old (s.d. 4.925) with a range of 21–52 years. Han people accounted for 98.6%, and ethnic minorities accounted for 1.4%. A total of 2985 women had a history of induced abortion, accounting for 11.0%, and they were included in the exposure group. The other 24,191 patients who had no history of abortion (including spontaneous abortion and induced abortion) were included in the control group. We compared the baseline data of the two groups. As shown in , there were significant differences in multiple variables, and the baseline data of the subjects in the two groups were unevenly distributed.

Table 1. Maternal baseline characteristics with history of induced abortion.

Outcome data and main results

The average pregnancy cycle for the 27,176 people examined was 273 days (s.d. 10.091) with a range of 193–300 days. A total of 1,531 women had preterm deliveries, and the preterm birth rate was 5.6% (95% CI 5.4–5.9%). The preterm birth rate was 5.5% (95% CI 5.2–5.8%) for women who had no history of abortion and 6.5% (95% CI 5.6–7.4%) for women who had a history of induced abortion. In Model A, the results of the single-factor analysis showed that the risk of preterm birth could be increased by a history of induced abortion, and the RR was 1.18 (95% CI 1.02–1.36). The multivariate analysis showed that in models B, C, and D, the effect of induced abortion on preterm birth was almost the same as that in Model A. The unadjusted and adjusted RRs are shown in .

Table 2. Unadjusted and adjusted RRs for preterm birth according to history of induced abortion.

Among the examined population, 313 women had an early preterm birth, with an early preterm birth rate of 1.2% (95% CI 1.0–1.3%). The incidence of early preterm birth was 1.8% (95% CI 1.3–2.3%) in the induced abortion group and 1.1% (95% CI 0.9–1.2%) in the nonabortion group. Without adjusting for potential confounders (Model A), a history of induced abortion was a risk factor for early preterm birth, with an RR of 1.65 (95% CI 1.23–2.21). After adjusting for different potential factors, the associations between induced abortion and early preterm birth did not change appreciably. The results of the four different models were consistent and stable. The results of different models are also shown in .

Other analysis

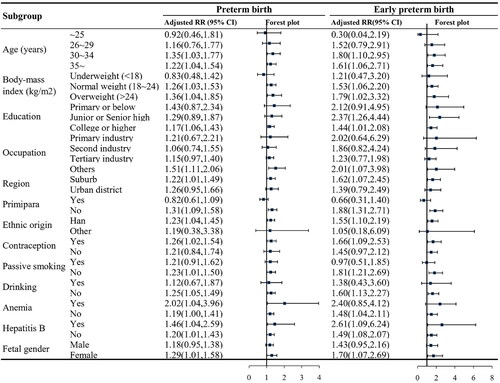

A subgroup analysis was performed using Model D. The association between a history of induced abortion and preterm birth was positive in most subgroups, as was the association between induced abortion history and early preterm birth. The subgroups included participants over 30 years old, participants of normal weight, overweight participants, participants with a college degree or above, suburban residents, Han participants, a history of birth, use of contraception, nonsmoking participants, nondrinking participants, participants with hepatitis B, participants without nonhepatitis B, and female infants. The results are shown in and Supplementary material Citation1.

Figure 2. Subgroup analysis of the relationship between a history of induced abortion and preterm birth (Note: Log-binomial regression models were used to estimate the RRs and 95% CIs; A subgroup analysis was performed according to the baseline characteristics after adjusting for other potential baseline risk factors; Some subgroups were not analyzed because of the small sample size.).

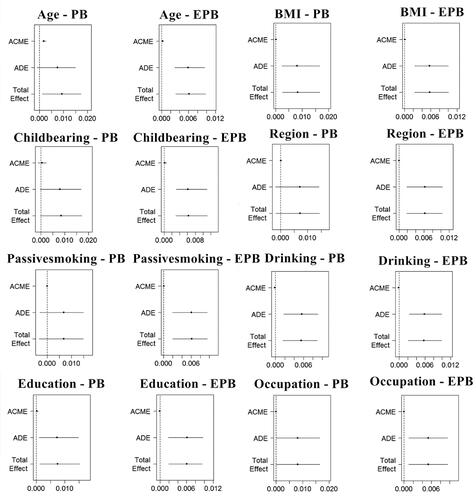

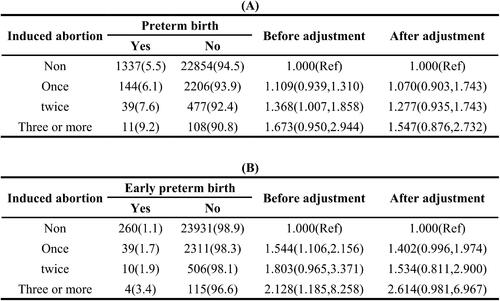

We discussed the mediation effects of 8 demographic data points on the history of induced abortion and subsequent preterm birth. The results are shown in and Supplementary material Citation2. After excluding the mediation effect, the direct effect of induced abortion history on follow-up preterm birth was still significantly different. As the number of abortions increased, the RR value of follow-up preterm birth increased, but some values were not significant. The results are shown in .

Figure 3. Mediation effect analysis of a history of induced abortion and preterm birth (Note: PB - Preterm birth, EPB - Early preterm birth, BMI - Body Mass Index, ACME - average causal mediation effect, ADE - average direct effect; The independent variable was induced abortion, and the outcome variable was preterm birth and early preterm birth.).

Figure 4. Analysis of the relationship between the number of induced abortions and preterm birth. (Note: A - Preterm birth, B - Early preterm birth; Log-binomial regression models were used to estimate the RRs and 95% CIs; Adjust for age, childbearing history, BMl, region, passive smoking, drinking, education and occupation.).

Discussion

Prior to this study, we found more than 10 studies on prior induced abortions and the risk of preterm birth [Citation8–18]. Nearly half of the studies were positive, and half were negative. These controversial results from different populations indicate that the relationship between abortion history and preterm birth is worth studying. Therefore, we conducted this retrospective cohort study in China, and we found that induced abortion increased the risk of preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies, and the association was more obvious in low gestational age.

Preterm birth seriously harms the health of newborns and brings a significant economic burden to society [Citation25]. In 2016, among children under 5 years old globally, complications from preterm birth were the leading cause of death, accounting for approximately 16.0% of all deaths and 35.0% of new-born deaths [Citation6]. More than one million premature babies are born in China every year, accounting for approximately 7.0% of all new-borns [Citation26]. In the study, the preterm birth rate was 5.6% in Dongguan. According to previous studies, in Guangdong Province, the preterm birth rate was 5.6% in 2001–2011 [Citation27] and 4.2% in 2014–2017 [Citation28]. Guangdong Province is one of the richest regions in China. The low preterm birth rate may be due to higher incomes and better medical conditions in this area. The abortion rates in China are high, ranging between 11.0% and 55.0% in previous published studies [Citation2]. The prevalence rate of induced abortion was 11.0% in our study, lower than that of the general population in China [Citation29]. The reason may be that our participants were younger, and none of them were immigrants, who are believed to have a higher abortion rate [Citation30].

We found three studies on prior induced abortions and risk of preterm birth in the Chinese population, and all of them were negative [Citation13,Citation15,Citation17]. One of the negative studies explored only the effect of mifepristone-induced early abortion and the outcome of subsequent pregnancy [Citation15]. One of the negative studies,which was conducted in Guangdong Province, the same population as our study, had a smaller sample size and did not adjust for some key variables [Citation13]. The sample size of another study was less than 300 [Citation17]. This may be the first explorative cohort study with a large sample on the history of induced abortion and preterm birth in China. For this cohort, we retrospectively selected 30,525 participants and followed up on their pregnancy outcomes. We adjusted different baseline data and established four models to verify the stability of the results. The results showed that a history of induced abortion increased the risk of preterm birth and that this link became stronger in early preterm birth. The associations were consistent across multiple subgroups defined by various baseline characteristics.

In addition to whether a history of induced abortion will increase the risk of preterm birth, whether the risk of preterm birth will increase with the number of previous induced abortions is also controversial. Lang [Citation10] found that only two or more induced abortions can cause subsequent preterm birth. In a study from Denmark [Citation11], a history of induced abortion increased the risk of preterm birth only in women with interpregnancy intervals of more than 12 months, and it was not related to the number of previous abortions. However, a study from North America found that a history of abortions can increase the risk of preterm labor and that the risk increased with the frequency of abortions [Citation8]. Due to the limited length of the article and the insufficient sample size, although we have detailed data on the number of abortions, we did not analyze the relationship between the number of abortions and preterm birth. In the future, we will expand the sample size to explore this relationship.

In contrast, the findings of induced abortions on subsequent early preterm birth were more consistent. An observational study of 30,0858 women in Finland found that women with a history of induced abortion were more likely to have early preterm birth (<28 gestational weeks), and this effect exhibited adose–response relationship [Citation31]. Martius [Citation32] observed a significant increase in the risk of early preterm birth (<32 + 0 gestational weeks) associated with previous induced abortions (OR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.57–2.13), and the risk increased with the number of abortions. Hardy [Citation8] and Henriet [Citation9] reported that women with prior induced abortions had a significantly higher risk of preterm birth in a subsequent pregnancy and that the risk increased with decreasing gestational age. Our study also verified the above results.

In the subgroup analysis, we found that in some subgroups, for example, older than 30 years, BMI ≥18, having undergone previous childbirth, etc., a history of induced abortion was associated with preterm birth. However, we lack literature on these subgroups for comparison. There were no significant differences in the results of some subgroups, and the sample size of these subgroups was often small. If we expand the sample size in the future, we may obtain different results.

Demographic data such as age, body mass index, education level and birth history were considered potential risk factors for premature birth [Citation33]. Mediation effects explain the relationship between risk factors and outcomes through mediating variables [Citation34]. The total effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable can be decomposed into direct effects and indirect effects. For the first time, we excluded the influence of these confounding factors by a mediation effect analysis to verify the relationship between abortion history and preterm birth. We found that after excluding the indirect effect of demographic data, there was still a significant difference in the direct effect of abortion history on subsequent preterm birth. Our results showed that there may be a dose-response between induced abortion and subsequent preterm birth; that is, the more abortions there are, the greater the risk of subsequent preterm birth. However, there were no significant differences in some subgroups. Li Ke [Citation13] reported that women who have had more than two miscarriages will have an increased risk of subsequent premature birth, and only one miscarriage will not increase this risk.

Because this report is only an observational study, it is difficult to explore the pathogenesis of induced abortion leading to subsequent preterm birth. Different studies have proposed specific mechanisms (such as intra-amniotic infection, antepartum hemorrhage, cervical incompetence, and preterm premature rupture of membranes) leading to preterm birth in women with a prior induced abortion [Citation8,Citation35]. However, all of these mechanisms need to be confirmed, and more experimental studies are needed.

Strict inclusion criteria were set, many influencing factors were adjusted, the factors of the fathers and infants were considered, and four models and mediation effect models were established, all of which increased the credibility of our results. However, our study has some limitations. First, because the history of induced abortion is related to a person’s privacy, some women may conceal it and might be misclassified into the control group, which could lead to an underestimation of the associations between a history of induced abortion and preterm birth. Second, although we had nearly 30,000 samples, the sample size of some subgroups is still insufficient, and this is a single-center study. Third, although we have adopted multi-factor analysis to control the impact of many variables on the results, it is still not comprehensive [Citation36]. Finally, gestational age at abortion should also be considered as an important variable for analysis [Citation37], but we did not investigate it, so we cannot analyze this variable.

Although we find that induced abortion increases the risk of premature delivery in subsequent pregnancy, it is difficult for women in the reproductive years to understand all the potential short- and long-term negative effects of induced abortion. Therefore, the government should formulate more effective public health policies and implement extensive publicity to help women adopt scientific contraceptive methods to limit the need for induced abortion. As a large number of women undergo abortions in China every year, taking targeted measures to reduce the need for pregnancy termination may be effective in reducing the rates of premature birth in this country.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Dongguan Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital September 30, 2018 (No. [23] 2018). All participants signed informed consent before the examination.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors contributed a lot to this research. Conception and design of the study: YJY, JB, ZXJ, WSS, HWC. Gathering of data: YJY, JB, ZXJ, WSS, HWC; Analysis and interpretation of the data: HWC, YJY. Drafting of the manuscript: HWC, YJY; Critical revision of the manuscript: JB, ZXJ, WSS; Approval of the final version for publication: all the author.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (19.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the obstetricians, pediatricians, pathologists, statisticians and other participants involved in the birth defects monitoring program and NFPHEP in Dongguan City. The authors also thank Mr. Ri-Hui Liu for his great support and help in the statistical analysis and writing of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the policy, the original data of this study cannot be shared.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, et al. Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1338–1345.

- Qian X, Tang S, Garner P. Unintended pregnancy and induced abortion among unmarried women in China: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):1.

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group Induced abortion. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(6):1160–1169.

- Zeng J, Zou G, Song X, et al. Contraceptive practices and induced abortions status among internal migrant women in Guangzhou, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:552.

- Wang C. Induced abortion patterns and determinants among married women in China: 1979 to 2010[J]. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(43):159–168.

- Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–e46.

- Strandell A, Lindhard A, Eckerlund I. Cost–effectiveness analysis of salpingectomy prior to IVF, based on a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(12):3284–3292.

- Hardy G, Benjamin A, Abenhaim HA. Effect of induced abortions on early preterm births and adverse perinatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35(2):138–143.

- Henriet L, Kaminski M. Impact of induced abortions on subsequent pregnancy outcome: the 1995 French national perinatal survey. BJOG. 2001;108(10):1036–1042.

- Lang JM, Lieberman E, Cohen A. A comparison of risk factors for preterm labor and term small-for-gestational-age birth. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):369–376.

- Zhou W, Sorensen HT, Olsen J. Induced abortion and subsequent pregnancy duration. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(6):948–953.

- Makhlouf MA, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with prior spontaneous or induced abortions. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(9):765–772.

- Ke L, Lin W, Liu Y, et al. Association of induced abortion with preterm birth risk in first-time mothers. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5353.

- Prunet C, Delnord M, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, et al. Risk factors of preterm birth in France in 2010 and changes since 1995: results from the French national perinatal surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46(1):19–28.

- Chen A, Yuan W, Meirik O, et al. Mifepristone-induced early abortion and outcome of subsequent wanted pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(2):110–117.

- Parazzini F, Ricci E, Chiaffarino F, et al. Does induced abortion increase the risk of preterm birth? Results from a case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69(1):40–45.

- Lao TT, Ho LF. Induced abortion is not a cause of subsequent preterm delivery in teenage pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(3):758–761.

- Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Induced abortion: not an independent risk factor for pregnancy outcome, but a challenge for health counseling. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(8):587–592.

- Jiang B, Liu J, He W, et al. The effects of preconception examinations on birth defects: a population-based cohort study in Dongguan City, China. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(16):2691–2696.

- Jiang B, He WC, Yu JY, et al. History of IUD utilization and the risk of preterm birth: a cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(2):349–358.

- Li S, Zhang Y, Feldman MW. Birth registration in China: practices, problems and policies. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2010;29(3):297–317.

- Liu J, Zhang S, Liu M, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy infection with hepatitis B virus and the risk of preterm birth: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(6):e624–e632.

- Dambha-Miller H, Day AJ, Strelitz J, et al. Behaviour change, weight loss and remission of type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study. Diabet Med. 2020;37(4):681–688.

- Chen M, Ma Y, Ma T, et al. The association between growth patterns and blood pressure in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study of seven provinces in China. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23(12):2053–2064.

- Frey HA, Klebanoff MA. The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21(2):68–73.

- Chen C, Zhang JW, Xia HW, et al. Preterm birth in China between 2015 and 2016. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(11):1597–1604.

- He JR, Liu Y, Xia XY, et al. Ambient temperature and the risk of preterm birth in Guangzhou, China (2001-2011). Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(7):1100–1106.

- Miao H, Li B, Li W, et al. Adverse birth outcomes in Guangdong Province, China, 2014–2017: a spatiotemporal analysis of 2.9 million births. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e030629.

- Hesketh T, Lu L, Xing ZW. The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1171–1176.

- Pérez G, Ruiz-Muñoz D, Gotsens M, et al. Social and economic inequalities in induced abortion in Spain as a function of individual and contextual factors. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(1):162–169.

- Klemetti R, Gissler M, Niinimäki M, et al. Birth outcomes after induced abortion: a nationwide register-based study of first births in Finland. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(11):3315–3320.

- Martius JA, Steck T, Oehler MK, et al. Risk factors associated with preterm (<37 + 0 weeks) and early preterm birth (<32 + 0 weeks): univariate and multivariate analysis of 106 345 singleton births from the 1994 statewide perinatal survey of Bavaria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;80(2):183–189.

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84.

- Zhang Z, Zheng C, Kim C, et al. Causal mediation analysis in the context of clinical research. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(21):425.

- Zhou Q, Zhang W, Xu H, et al. Risk factors for preterm premature rupture of membranes in chinese women from urban cities. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;127(3):254–259.

- Rosa PAD, Miglioli C, Caglioni M, et al. A hierarchical procedure to select intrauterine and extrauterine factors for methodological validation of preterm birth risk estimation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):306.

- Kc S, Gissler M, Klemetti R. The duration of gestation at previous induced abortion and its impacts on subsequent births: a nationwide registry-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(5):651–659.