Abstract

Background

Twin pregnancy is associated with higher risks of adverse perinatal outcomes for both the mother and the babies. Among the many challenges in the follow-up of twin pregnancies, the mode of delivery is the last but not the least decision to be made, with the main influencing factors being amnionicity and fetal presentation. The aim of the study was to compare perinatal outcomes in two European centers using different protocols for twin birth in case of non-cephalic second twin; the Italian patients being delivered mainly by cesarean section with those in Belgium being routinely offered the choice of vaginal delivery (VD).

Methods

This was a dual center international retrospective observational study. The population included 843 women with a twin pregnancy ≥ 32 weeks (dichorionic or monochorionic diamniotic pregnancies) and a known pregnancy outcome. The population was stratified according to chorionicity. Demographic and pregnancy data were reported per pregnancy, whereas neonatal outcomes were reported per fetus. We used multiple logistic regression models to adjust for possible confounding variables and to compute the adjusted odds ratio (adjOR) for each maternal or neonatal outcome.

Results

The observed rate of cesarean delivery was significantly higher in the Italian cohort: 85% for dichorionic pregnancies and 94.4% for the monochorionic vs 45.2% and 54.4% respectively in the Belgian center (p-value < 0.001). We found that Belgian cohort showed significantly higher rates of NICU admission, respiratory distress at birth and Apgar score of < 7 after 5 min. Despite these differences, the composite severe adverse outcome was similar between the two groups.

Conclusion

In this study, neither the presentation of the second twin nor the chorionicity affected maternal and severe neonatal outcomes, regardless of the mode of delivery in two tertiary care centers, but VD was associated to a poorer short-term neonatal outcome.

Introduction

The incidence of twin pregnancy is rising progressively with the main factors cited as delayed childbirth, advanced maternal age at conception and the widespread use of assisted reproduction techniques [Citation1]. The twin birth rate has also increased by just under 70% between 1980 and 2006 [Citation1]. Twin pregnancy is known to be associated with higher risks for mother and babies; for maternal mortality, a 2.5-fold increase has been reported compared to singleton pregnancies, with a preterm birth rate of 50%, which accounts for approximately 65% of neonatal deaths among multiple births [Citation2–6]. The risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity is even higher in monochorionic (MC) pregnancies due to the near ubiquitous presence of placental anastomoses, responsible for twin-to-twin syndrome (TTTS) and twin anaemia-polycythaemia sequence (TAPS); and unequal placental sharing which is responsible for selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) and carries an even worse prognosis [Citation7–11].

Among the many challenges of managing twin pregnancy, the mode of delivery is one of the last but most important decisions to be made prior to birth, with the main influencing factors being amnionicity and fetal presentation. Whereas there is near consensus on performing cesarean delivery (CD) for all monoamniotic or non-cephalic-presenting twins, the standard of care for the group of non-cephalic second twins, accounting for over one-third of the cases, is still a matter of debate [Citation12]. The reported rates of CD for the second twin range from 0.5% to more than 10% [Citation13–18] and for both twins from 19.6% to 43.8% [Citation19,Citation20]. These large ranges probably reflect wide variations in practice related to heterogeneous indications for CD and suggest that there is a rate of additional surgical procedures in cases where vaginal delivery (VD) could have been attempted [Citation10].

In 2013 the Twin Birth Study (TBS) showed that mode of birth did not influence the risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity, regardless of chorionicity [Citation19,Citation21]. These findings were confirmed in the French JUMODA study (JUmeaux MODe d’Accouchement), which demonstrated that planned CD, between 32 and 37 weeks of gestation was associated with poorer neonatal outcomes when compared to planned vaginal birth [Citation20]. The same group in 2021, went on to demonstrate that uncomplicated monochorionic twin pregnancy is not associated with a higher rate of composite intra-partum mortality, neonatal morbidity and mortality when VD is planned from 32 weeks of gestation [Citation22–24]. Updated recommendations from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) [Citation25], and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [Citation26] guidelines have both incorporated these data and now support VD for all patients with uncomplicated diamniotic twin pregnancies from 32 weeks, where the presenting fetus is in the vertex position. However, despite numerous guidelines in favor of vaginal birth, the CD rate for twin pregnancies remains relatively high, with the OECD (Organization for European Co-operation and Development) already concerned about the impact of that ever increasing CD rates on the health and well-being of mothers and babies [Citation27–35]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has also stated that a CD rate higher than 10–15% should be never justified [Citation36]. In order to achieve this goal, new indications about the systemic use of CD for twin pregnancies, patients with prior history of cesarean section and those with breech presentations at term are requested [Citation37–40]. For sure, the implementation of obstetrics training and simulation programs, the use of clinical protocols with the latest evidence could lead to the reduction of unnecessary CD [Citation41].

The aim of this study was first to compare perinatal outcomes in twin pregnancies within two European centers, each using different protocols regarding mode of birth; and second, to provide further evidence regarding unnecessary Robson Class 8 cesarean sections (all women with twin pregnancies, including those with uterine scars).

Methods and materials

This was a bicentric international retrospective observational study conducted in two university hospitals in Belgium and Italy. The population included all women with a twin gestation ≥ 32 weeks (dichorionic or monochorionic diamniotic) and a known pregnancy outcome between January 1st 2015, and May 31st 2021.

Exclusion criteria included: pregnancies with unknown outcomes, non-live births (terminations of pregnancy and intrauterine deaths), patients with contraindications for VD (first twin with lies other than longitudinal), more than one previous CD, previous myomectomy, placenta previa, TTTS, major fetal malformations, maternal contraindications), monochorionic monoamniotic pregnancies and higher order pregnancies.

Neonatal and maternal outcomes resulting from 2 different care-pathways were compared: the first group of patients delivered at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy, where all twin pregnancies with a non-cephalic second twin were subjected to elective CD and VD was proposed just in case of both twins in cephalic presentation if patients were strongly motivated; the second group delivered at Brugmann University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium, which routinely offered VD in case of non-cephalic second twin, where there is an inner protocol for breech delivery and an entrained team. Both centers agreed in setting the date of delivery, independently from the modality, starting from 36 + 0 weeks for the MC and from 37 + 0 for the BC pregnancies. Always according to inner protocols, steroids were administrated respectively until 34 + 0 and 37 + 0 weeks of GA, respectively in case of VD or CD.

The study was approved by both Hospital ethical boards (identification numbers: IST DIPUSVSP-03-11-2178 and CE2021/124). Data collected included maternal characteristics such as age, race (white, black, others), pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), parity, previous vaginal and cesarean deliveries, smoking status, comorbidities (chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, preexisting pulmonary, renal and hepatic problems, cardiac disease, endocrine disorders e.g. hypo or hyperthyroidism, psychiatric disorders, haematological disorders, diagnosed thrombophilia, autoimmune diseases, cancer, HIV) as well as obstetrics characteristics and maternal complications such as, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), gestational hypertension (GHTN), preeclampsia, eclampsia, HELLP (Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets) Syndrome and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

For the obstetrical outcomes we considered: gestation age (GA) at delivery, twins’ presentation at birth and mode of delivery (VD or CD). In case of VD, use of vacuum or forceps or active management with internal podalic version for the second twin were recorded. Inter-twin delivery delay expressed in minutes, fetal distress (bradycardia, recurrent late or variable decelerations) of 1 or both twins, intra-partum CD, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) > 1000 mL, need for blood transfusion, maternal admission to intensive care unit (ICU) or death were also considered. Composite adverse obstetrical outcome (CAOO) was defined as the presence of at least one of the following outcomes: PPH, blood transfusion, ICU admission, death.

For the neonatal outcomes we analyzed: birth weight, APGAR score at 5 min < 7, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome at birth (RDS), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), birth trauma (subdural hematoma, intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage, spinal-cord injury, basal skull fracture, peripheral-nerve injury present at discharge from hospital, or clinically significant genital injury), seizures occurring at less than 24 h of age or requiring two or more drugs, hypotonia for a least 2 h, stupor, decreased response to pain, or coma, request to perform an intubation and ventilation for at least 24 h, tube feeding for 4 days or more, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and neonatal death. The criteria for NICU admission were comparable in both centers (GA at birth of ≤ 32 weeks of gestation, birth-weight of ≤ 1500 gr, signs of respiratory distress, hemodynamic instability, metabolic problems needing central venous access placement and intensive care, perinatal asphyxia defined according to the ACOG and American Academy of Paediatrics’ criteria, and need for exchange transfusion) [Citation42]. Composite severe adverse neonatal outcome was defined as the presence of at least one of the following outcome: neonatal death, birth trauma, seizure, interventricular hemorrhage, hypotonia, coma, intubation, tube feeding.

The comparison of maternal and neonatal outcomes in both groups were first stratified according to the chorionicity and then adjusted for all the statistically significant features.

The primary outcome was the impact of planned mode of delivery – regardless of 2nd twin presentation – on composite adverse obstetric outcomes and severe adverse neonatal outcomes. The secondary outcomes included each individual variable of the composite outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with R software and SPSS 26 statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics). Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]), whereas categorical variables were expressed as number (frequency), unless otherwise indicated. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test to test the normal distribution of continuous variables, and the Levene test to examine the equality of variances. Furthermore, we used either the t test or the Mann Whitney U test to compare the means of both groups. For comparison of the categorical variables, we used either the Fisher exact test or the Pearson chi-squared test as indicated.

Demographic and pregnancy data were reported per pregnancy, whereas neonatal outcomes were reported per fetus. The package "mice” was used to perform multiple imputations for missing values by classification and regression trees. We used multiple logistic regression models to adjust for possible confounding variables (maternal age, BMI, origin, nulliparity, chronic hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, and GA at delivery) and to compute the adjusted odds ratio (adj OR) for each maternal or neonatal outcome. A final analysis was conducted to compare the rate of NICU admission in both centers according to the mode of delivery for twins with a cephalic-cephalic presentation. Statistical significance was assumed when the p-value was ≤ 0.05. The manuscript was prepared according to STROBE guidelines.

Results

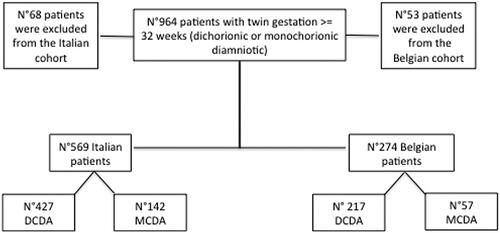

Overall, we identified 964 patients with a twin gestation ≥ 32 weeks of which 843 patients met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for analysis (). Among these patients, 569 were followed in the Italian center with 274 from Belgium. Patients were stratified according to the chorionicity: dichorionic-diamniotic (DCDA) pregnancies (427 in Italy and 217 in Belgium) and monochorionic-diamniotic (MCDA) pregnancies (142 in Italy and 57 in Belgium). Baseline characteristics of the study population and mode of delivery were reported according to the chorionicity ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population and mode of delivery stratified according to the chorionicity.

The Italian population was older (mean age of 35 years old vs. 31 years old for DCDA and 34 years old vs 31 for MCDA, p-value < 0.001) and with a higher proportion of nulliparous patients (70% vs 31.8% for DCDA and 58.5 vs 38.6% for MCDA, p-value < 0.001). The Belgian population had a higher mean BMI (22.40–29.29, p-value < 0.001) and more African patients (19.4% vs 2.8% for DCDA and 15.8% vs 2.8% for MCDA, p-value < 0.001). Despite these demographics, we found a higher rate of preeclampsia in the Italian DCDA group (13.1% vs 5.5%). The Belgian group had a higher incidence of GDM in case of DC pregnancy (24.0% vs. 16.9%, p value 0.035). Both groups had similar rates of cephalic and breech presentations of the first twin, cephalic in the 71.9% and 77.2% of the DCDA pregnancies and 70% and 88% for the MCDA pregnancies, respectively for the Italian and the Belgian group. There were no differences in the relative proportions of cephalic and breech presentations of the second twin between the two centers, for both DCDA and MCDA pregnancies.

The rate of CD was significantly higher in the Italian cohort, with a rate of 85% for DCDA pregnancies and 94.4% for MCDA vs 45.2% for DCDA pregnancies and 54.4% for MCDA pregnancies registered in the Belgian group (p-value < 0.001).

CD performed during labor (33.7% vs 9.2% for the DCDA and 22.5% and 5.3% for the MCDA) and for the extraction of the second twins (1.9 vs 0.9 for the DCDA and 0.7 vs 0% for MCDA), were significantly higher in the Italian population, (p-value < 0.001). VD occurred in 53.9% of Belgian vs 13.1% of Italian patients for DCDA pregnancies, while 45.6% of Belgium MCDA patients delivered vaginally vs 4.9 in the Italian cohort (p-value < 0.001). The Belgium cohort had a higher rate of instrumental delivery 10.1% vs 2.6% for DCDA and 3.5% vs 1.4% for MCDA (p-value 0.001), consequently to the higher rate of VD in the Belgian cohort.

Neonatal and maternal outcomes are summarized in .

Table 2. Comparison of neonatal and maternal outcomes in both groups stratified according to the chorionicity.

There was no statistical difference in CAOO between the two groups, following adjustment for: maternal age, BMI, nulliparity, chronic hypertension, GDM, and gestational age at delivery. The rate of postpartum hemorrhage > 1000 cc was higher in the Belgian group with DC pregnancies, but this did not translate into a higher rate of blood transfusion in this cohort.

With regard to the neonatal outcomes, we found that the in Belgian cohort showed significantly higher rates of NICU admission (10% vs 19.4% in the DCDA and 13.5% vs 35.1% in the MCDA; adj OR: 0.141 ([95%CI: 0.078–0.248], and 0.124 [95%CI:0.051–0.281], respectively), respiratory distress at birth (5.5% vs 34.6% in DCDA and 4.6% vs 58%; adj OR: 0.583 [95%CI: 0.034–0.097)], and 0.024 [95%CI: 0.009–0.055], respectively) and Apgar score of < 7 after 5 min (0.6% vs 6.2% in DCDA and 0.7% and 7.9%; %; adj OR: 0.062 [95%CI: 0.018–0.179)], and 0.121 [95%CI: 0.017–0.560], respectively). Despite these differences the composite severe adverse outcome was similar between the two groups.

A sub-analysis was made for the pregnancies where both twins were cephalic, regardless of chorionicity, as shown in . Among these patients, 71.48% of Italian patients had a planned CD vs 28.07% of Belgian patients (p-value > 0.001). No differences were found in the rates of ‘emergency’ or intrapartum CD: Italian 27.75% vs Belgian 25%. However, we observed a significant difference in NICU admission, with a higher rate of transfer in the Belgian center, especially for first cephalic twins born by CD (25% vs 6.4%, p-value 0.013). In this subgroup of pregnancies, the rate of VD was respectively 25.2% in the Italian and 71.05% for the Belgian group (p-value 0.001). No differences were observed in the rate of NICU admission for either the first or the second twin born by VD. No significant difference was found in terms of rate of CD for the second twin between the two centers (3.32% vs 0.87%) nor for NICU admissions in this group.

Table 3. Patients with both twins in cephalic presentation independently from the chorionicity, comparison between rate of CD, VD and NICU admission for the first and the second twin.

Discussion

This study compared two different twin birth protocols in two different European university hospitals. The Italian protocol allows attempts at vaginal birth in very motivated patients with cephalic/cephalic presentations, while in Belgium, VD is proposed in all diamniotic twins where the first twin is cephalic regardless of the presentation of the second twin.

We found no differences in the composite obstetric nor the composite severe adverse neonatal outcomes in the two centers, in agreement with other previously published studies.

As described in the TBS in 2013 [Citation19] and the JUMODA study in 2017 [Citation20], there were no differences in fetal or neonatal outcomes by planned mode of delivery of mono- or dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies. However, our study showed some poorer short-term neonatal outcomes for vaginal birth, reflected in higher rates of NICU admission, respiratory distress at birth and Apgar score < 7 after 5 min, but without any difference in the primary composite adverse neonatal outcomes [Citation22].

In the TBS study, none of these factors (respiratory distress at birth, NICU admission and APGAR score < 7) were considered as serious neonatal morbidity [Citation19].

Although no differences were found in the CAOO, a higher rate of PPH was observed in the Belgian population, and on this matter the literature is somewhat contradictory. There is evidence showing that CD, especially those which eventuate during a trial of labor, are associated with an increased risk for PPH compared to spontaneous VD [Citation18, Citation27, Citation43]. Korb et al. showed that CD for second and for both twins is associated with higher risks of severe acute maternal morbidity than VD and severe PPH was the main contributor [Citation44], while Easter et al. report that women with twin pregnancies undergoing a trial of labor have a higher risk of maternal morbidity than those undergoing an elective CD; primarily as a result of haemorrhage [Citation45]. di Marco et al. report that the risk of PPH in twin pregnancies is higher in case of episiotomy, increasing neonatal weight and operative VD, while it decreases in case of preterm delivery [Citation46]. In our study, we found that 17.4% of Italian patients had a PPH (with EBL > 1000 cc) in contrast to 24% in the Belgian center, most of these cases being delivered by cesarean section. Despite higher rates of PPH observed in the Belgian population, there was no difference in rate of blood transfusion nor admission to the ICU. It is also important to highlight that the Belgian group is currently analyzing its data over the last few years because of a higher-than-average incidence of significant PPHs during vertex vaginal birth.

Obstetrical teams competent in the management of vaginal breech labor and birth are becoming increasingly rare, and this has consequences for twin delivery when the second baby is in a non-cephalic presentation. FIGO recommendations state that in the absence of an experienced team, it is reasonable to offer primary cesarean section [Citation47]. On the other hand, our data demonstrates once again that VD should be the first and predominant option for all pregnancies with both twins in cephalic presentation. The sub-analysis of pregnancies with both twins in cephalic presentation demonstrated that 72.75% of Italian patients underwent a planned CD, without attempting a VD. All these patients were hypothetical candidates for planned induction of labor. Precisely, only 67 (19 with previous CD and 48 intrapartum CD) were the patients who would have eventually benefit from a CD. If all the other patients would have attempted and achieved a VD, the rate of CD in twins (Robson’s class 8) with both cephalic presentation would have decreased from 71.48% to 27.68%; this rate would be comparable to the one in the Belgian population and in the literature [Citation19,Citation20].

We believe that VD could be a safe option in twin pregnancy and the improvement of clinical protocols with the latest evidence can lead to the reduction of unnecessary CD in this group of patients.

The strength of this study lies in the dual center design, where both centers follow very similar guidelines for prenatal, postnatal, and neonatal management, differing only in terms of selection for mode of birth based on the presentation of the second twin. Another strength of this study is the large sample size collected.

The main limitation of our study is the retrospective design; however, patients’ variables and outcomes were prospectively recorded in electronic medical files in both centers, thereby reducing the chances of missing and/or inaccurate data.

Conclusion

It is well-established that access to information and communication among healthcare providers and patients can improve pregnancy outcomes [Citation48–50]. One of the biggest issues in Italy is that women with twin pregnancies frequently believe that cesarean birth is their only option. One of the first steps in reducing CD rate for twins, is to provide patients with accurate and evidence-based information regarding the advantages and relative safety of vaginal twin birth. Our study adds to the literature in this regard, by providing additional reassuring data supportive of vaginal birth when the presenting twin is cephalic.

In conclusion, we have shown that in tertiary care centers, both chorionicity and presentation of the second twin have no detrimental impact on severe neonatal and maternal outcomes, regardless of the mode of delivery, but it could be associated to a poorer short-term neonatal outcome. Additional prospective studies will be needed to clarify the impact of mode of delivery on short term perinatal outcomes and on the rate of PPH.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all participating patients and study team members for their time spent on this project. We thank the Ministry of Health of Italy: current research year 2024.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Khalil A, Rodgers M, Baschat A, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: role of ultrasound in twin pregnancy: ISUOG guidelines. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(2):1–10. doi:10.1002/uog.15821.

- Chan A, Scott J, Nguyen AM, et al. Pregnancy outcome in South Australia 2007. Adelaide: Pregnancy Outcome Unit, SA Health, Government of South Australia; 2008.

- Elliott JP. High-order multiple gestations. Semin Perinatol. 2005;29(5):305–311. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2005.08.001.

- Laws. Australia’s mothers and babies 2006, summary. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008 Dec 9 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies-2006/summary

- Tucker J, McGuire W. Epidemiology of preterm birth. BMJ. 2004;329(7467):675–678. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7467.675.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Multiple pregnancy: the management of twin and triplet pregnancies in the antenatal period. London: RCOG Press; 2011 Sep.

- Badr DA, Bevilacqua E, Carlin A, et al. Antenatal management and neonatal outcomes of monochorionic twin pregnancies in a tertiary teaching hospital: a 10-year review. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;41(8):1199–1204. doi:10.1080/01443615.2020.1854698.

- Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, Hughes K, et al. The hidden mortality of monochorionic twin pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(10):1203–1207. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10948.x.

- Badr DA, Carlin A, Kang X, et al. Evaluation of the new expert consensus-based definition of selective fetal growth restriction in monochorionic pregnancies. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(12):2338–2344. doi:10.1080/14767058.2020.1786053.

- Mohamad KR, Saheb W, Jarjour I, et al. Delayed-interval-delivery of twins in didelphys uterus complicated with chorioamnionitis: a case report and a brief review of literature. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(17):3318–3322. doi:10.1080/14767058.2020.1818211.

- Navaratnam K, Khairudin D, Chilton R, et al. Foetal loss after chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis in twin pregnancies: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Prenat Diagn. 2022;42(12):1554–1561. doi:10/pd6237-sup-0003-table_s3.docx.

- Vogel JP, Holloway E, Cuesta C, et al. Outcomes of non-vertex second twins, following vertex vaginal delivery of first twin: a secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):55. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-55.

- Korb D, Deneux-Tharaux C, Seco A, et al. Risk of severe acute maternal morbidity according to planned mode of delivery in twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(3):647–655. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002788.

- Schmitz T, Carnavalet CdC, Azria E, et al. Neonatal outcomes of twin pregnancy according to the planned mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):695–703. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318163c435.

- Wen SW, Fung KFK, Oppenheimer L, et al. Occurrence and predictors of cesarean delivery for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):413–419. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000110248.32558.fb.

- Yang Q, Wen SW, Chen Y, et al. Occurrence and clinical predictors of operative delivery for the vertex second twin after normal vaginal delivery of the first twin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(1):178–184. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.084.

- Yang Q, Wen SW, Chen Y, et al. Neonatal death and morbidity in vertex-nonvertex second twins according to mode of delivery and birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):840–847. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.132.

- Wenckus DJ, Gao W, Kominiarek MA, et al. The effects of labor and delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes in term twins: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121(9):1137–1144. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12642.

- Barrett JFR, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, et al. A randomized trial of planned cesarean or vaginal delivery for twin pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1295–1305. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214939.

- Schmitz T, Prunet C, Azria E, et al. Association between planned cesarean delivery and neonatal mortality and morbidity in twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):986–995. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002048.

- Zafarmand MH, Goossens SMTA, Tajik P, et al. Planned cesarean or planned vaginal delivery for twins: secondary analysis of randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(4):582–591. doi:10.1002/uog.21907.

- Schmitz T, Korb D, Azria E, et al. Perinatal outcome after planned vaginal delivery in monochorionic compared with dichorionic twin pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(4):592–599. doi:10.1002/uog.23518.

- Verbeek L, Zhao DP, Te Pas AB, et al. Hemoglobin differences in uncomplicated monochorionic twins in relation to birth order and mode of delivery. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2016;19(3):241–245. doi:10.1017/thg.2016.23.

- Lopriore E, Holtkamp N, Sueters M, et al. Acute peripartum twin-twin transfusion syndrome: incidence, risk factors, placental characteristics and neonatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(1):18–24. doi:10.1111/jog.12114.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine. Practice bulletin no. 169: multifetal gestations: twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e131–e146. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001709.

- Overview | Twin and triplet pregnancy | Guidance | NICE; 2019 Sep 4 [cited 2023 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng137

- Chen J, Shen H, Chen YT, et al. Experience in different modes of delivery in twin pregnancy. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0265180. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265180.

- OECD. Health at a glance 2011: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing; 2011. doi:10.1787/helath_glance-2011-en.

- Deneux-Tharaux C, Carmona E, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):541–548. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000233154.62729.24.

- Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet Lond Engl. 1985;2(8452):436–437.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/gazzetta/serie_generale/caricaDettaglio?dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2015-06-04&numeroGazzetta=127

- Belvis AD, Neri C, Angioletti C, et al. A multi-approach management intervention can lower C-section rate trends: the experience of a third level referral center. de Belvis A.G., Neri C., Angioletti C., Carducci B., Ferrazzani S., Lanzone A., Caruso A. J Hosp Adm. 2018;7:15–22. doi:10.5430/jha.v7n6p37.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Caesarean section. RCOG Press; 2011 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115309/

- Badr DA, Al Hassan J, Salem Wehbe G, et al. Uterine body placenta accreta spectrum: a detailed literature review. Placenta. 2020;95:44–52. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2020.04.005.

- Ramadan MK, Ramadan K, El Tal R, et al. How safe is high-order repeat cesarean delivery? An 8-year single-center experience in Lebanon. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(8):1370–1377. doi:10.1111/jog.14311.

- Vayssière C, Benoist G, Blondel B, et al. Twin pregnancies: guidelines for clinical practice from the french college of gynaecologists and obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(1):12–17. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.045.

- Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Huertas E, et al. Planned elective repeat caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for women with a previous caesarean birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD004224. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004224.pub3.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–1383. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3.

- Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the rise and fall of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):20–25. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.039.

- Bevilacqua E, Jani JC, Meli F, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in breech presentation at term: a comparison between 2 third level birth center protocols. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;2(4):100086. doi:10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100086.

- Parasiliti M, Vidiri A, Perelli F, et al. Cesarean section rate: navigating the gap between WHO recommended range and current obstetrical challenges. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(2):2284112. doi:10.1080/14767058.2023.2284112.

- American Collge of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Neonatal encephalopathy and cerebral palsy: executive summary. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):780–781. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000120142.83093.30.

- Sato Y, Emoto I, Maruyama S, et al. Twin vaginal delivery is associated with lower umbilical arterial blood pH of the second twin and less intrapartum blood loss. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(19):3067–3071. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1118039.

- Korb D, Deneux-Tharaux C, Goffinet F, et al. Severe maternal morbidity by mode of delivery in women with twin pregnancy and planned vaginal delivery. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4944. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61720-w.

- Easter SR, Robinson JN, Lieberman E, et al. Association of intended route of delivery and maternal morbidity in twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(2):305–310. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001844.

- di Marco G, Bevilacqua E, Passananti E, et al. Multiple pregnancy and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage: retrospective analysis in a tertiary level center of care. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(3):446. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13030446.

- FIGO Working Group on Good Clinical Practice in Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Good clinical practice advice: management of twin pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;144(3):330–337. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12742.

- Acheampong K, Pan X, Kaminga AC, et al. Risk of adverse maternal outcomes associated with prenatal exposure to moderate-severe depression compared with mild depression: a fellow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:32–38. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.036.

- Traylor CS, Johnson JD, Kimmel MC, et al. Effects of psychological stress on adverse pregnancy outcomes and nonpharmacologic approaches for reduction: an expert review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(4):100229. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100229.

- Nicoloro-SantaBarbara J, Rosenthal L, Auerbach MV, et al. Patient-provider communication, maternal anxiety, and self-care in pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2017;190:133–140. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.011.