ABSTRACT

This account of practice discusses how we use action learning (AL) sets as part of the supervision process for quality improvement (QI) projects in healthcare. Reflecting on the synergies between QI and AL reveals that the questioning approach of both links closely with the Calgary Cambridge Communication model, taught in medicine, to guide medical interviews. While the Calgary Cambridge communication model provides the student with a framework in gathering a patient medical history, action learning helps them focus their attention on the type of questions they ask, active listening, and most importantly, reflecting on questions from their peers on their quality improvement projects. The student groups in this example are Physician Associates, also known as Physician Assistants in some countries, and are a new profession, recently introduced in Ireland. Communication skills might be the most important skill for healthcare workers to acquire, in order to ensure good patient outcomes.

Background

Quality improvement is the focus of senior managers and leaders in healthcare worldwide. While it rose to the forefront of the public’s attention with the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report (Institute of Medicine & Committee on Quality of Health Care in America Citation2000), the emphasis on patient safety and quality of care is now central to all standards of care and accreditation bodies, right across the healthcare sector. The Irish sector is no exception, with an emphasis on better patient safety, better value healthcare, resulting in reduced costs per capita, as proposed for the US health system (McCarthy et al. Citation2021). Physician Associates (PA) are post-graduate medically trained healthcare professionals, who are increasingly becoming essential assets to multidisciplinary medical teams worldwide following their evolution in the US during the 1960s. PAs attain a generalist scope of practice, and can take medical histories, perform physical examinations, order diagnostic investigations, make clinical diagnoses, formulate treatment regimens as well as assisting in surgical procedures. In Ireland, the first cohort of PAs graduated in 2017 (Joyce et al. Citation2019) with only 50 graduates to date in the country.

Due to the fast-paced nature of the Master’s in Physician Associate Studies, completing an eight-month didactic curriculum on medicine, together with fulfilling 2000 hours in clinical practice, students take their quality improvement projects to the planning stage only. However, all projects are registered under the clinical governance of the teaching hospital chosen, so that the other team members can progress the plan to implementation stage. The action learning process fits well with the Calgary Cambridge model of communication (Kurtz and Silverman Citation1996), introduced to students in the early part of their programme.

Action learning in healthcare has progressed on greatly since the work of Revans with the National Health Service in the 1960s (Brook Citation2010). According to Mathews et al. (Citation2017), hospitals frequently have processes in place to reflect on quality and safety issues but rarely have a dedicated infrastructure in place to take decisive action and integrate lessons learned, back into the organisation or group. However, in modern healthcare systems, clinical audit is an essential tool for improving patient care, and falls under the clinical governance pillar of quality and safety in Ireland. While in some countries clinical audit is mandatory, Ireland lags behind in terms of national support and legislative protection. However, there has been growing support for clinical audit in Ireland in recent years (HSE Citation2019). As part of continuing medical education, all doctors in Ireland are obliged to carry out a clinical audit each year. This obligation helps to get buy-in from them to support the PA students in carrying out quality improvement project plans with audit as the starting point of such projects. This paper describes how AL was used to support students in their QI journey, revealing that the questioning approach of both links closely with the Calgary Cambridge Communication model, which is taught in medicine.

Quality improvement projects

Many PA programmes do not include QI in their curricula even though it is recognised as an important skillset for PAs, and has emerged as a leadership and career track for them. Nearly one-third of programmes do not have QI in their curricula (Berkowitz et al. Citation2019). Reasons vary from lack of expertise to teach QI to lack of time for the topic (Berkowitz et al. Citation2014). Yet, Kindratt and Orcutt (Citation2017) found that following QI teaching in a PA programme, one-fifth of the students self-selected to participate in department-wide QI projects. According to Batalden and Davidoff (Citation2007) learning QI and carrying out QI are both special forms of experiential learning.

As part of this PA programme, students are required to carry out a QI project plan using the Lean Six Sigma framework, DMAIC. This framework works on the belief of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts, so that the waste-elimination approach of Lean along with the defect-free approach of Six Sigma together accelerate the improvement process (Improta et al. Citation2019). The focus of the projects is on changing the process of how patient care is delivered so that the emphasis is on the patient journey as the starting point of each topic (Gualandi et al. Citation2019). Examples of topics, chosen by the students clearly focus on access and patient flow (). The main challenges in healthcare in Ireland centre on accessing the health system.

Table 1. Sample QI projects.

Students are required to include a consultant doctor as their sponsor for their project plan. The consultant, any of the team members, or the student, can recommend the quality initiative. Once the student completes a clinical rotation on a service, which they feel could benefit from a quality initiative; they negotiate the topic with the team, including their sponsor. The benefits for PAs engaging in projects, which require them to communicate with as many members of the multidisciplinary team as possible, include the communication of this new role in the organisation and the opportunity to integrate the role into the team. Part of the project entails the student carrying out a stakeholder analysis. This exercise requires them to ask questions about individual team roles and to figure out how much power and influence each member night have in progressing their QI project plan. In essence, students use their leadership skills in working through the project steps. Within the PA programme, students undertake a number of self-development surveys in an effort to highlight where they can focus on personal development as they prepare to join a new profession. Reflecting and asking questions are features of this self-development so that students are prepared to use AL for their QI projects at the end of year one and throughout year two.

Connecting quality improvement with the action learning process

Edmonstone (Citation2014) suggests that balancing support and challenge, in addition to action and reflection, remain at the heart of successful action learning sets (ALS). The focus of the QI project assigned to the PA students is on the improvement of a process with a cost-neutral solution. The biggest challenge PA students have encountered over the years with the QI projects is the sponsor presenting them with a solution without exploring the steps in the process being investigated. According to Edmonstone (Citation2014), this approach may be what Revans labelled as puzzles rather than problems, having a top-down approach. For example, one project focused on reducing the number of patients unnecessarily attending an endocrine clinic, subsequently causing increased wait times for other patients needing to attend. On being presented with this topic by the consultant the student was advised that the results of a particular test should be reviewed by the consultant before deciding on whether or not a face-to-face visit to the hospital clinic was needed. The solution was already decided. According to Revans, problems are complex, with uncertainty and ambiguity about how improvements might be made (Pedler and Trehan Citation2008). Depending on one member of staff to review results is not sustainable during holiday periods or unforeseen absences. Starting with a solution, such as this example, can then colour the whole approach to the project without taking an open-minded questioning approach. It was only through the ALS meetings that these issues were highlighted. The use of open questions, reflecting, and asking more questions about the process in the clinical site allowed the student to uncover other issues. These included the need to set up an alert system when particular test results were available. Data analysis showed that test results were generally available sooner than expected but were not reviewed in a timely manner unless a healthcare professional checked for these results. In addition, document analysis of the patient charts showed that there was a mix of recent results being filed at the front of the relevant section, while other charts had the older results filed at the front of this section.

While active listening is at the core of the AL process, this skill is generally under-estimated by students undertaking QI projects. This has been noted when students are questioned about their understanding of the process being investigated. Their agreed follow-up steps at their ALS meeting very often involve them reverting to the multidisciplinary team to ask many more questions before their can map out a patient flow chart. This questioning will help them get to the root cause of the issue being investigated for improvement. By documenting all questions addressed to them at their ALS they can follow-up with responses to these at the next set meeting. Part of the QI project write-up requires the student to reflect on their learning of the QI process and the ALS. Inevitably, members of the healthcare team will propose a solution to the QI problem so the challenge for the student is to communicate the importance of letting the data reveal the root cause of the problem. Avoiding judgements on the current process is an important task for the PA student, who is new to healthcare, and is entering a new profession in Ireland. How the student deals with QI and the topic chosen will help them develop their social identity within healthcare, requiring them to draw on their communication and leadership skills. Gaining the trust of ALS members is a transferable skill, which PA students can use in the healthcare setting with the multidisciplinary team as they progress their QI project. While building trust may take a few sessions, once established it is difficult to interrupt (Joyce Citation2012). Finally, the personal development of the PA student in this inside-out process (Edmonstone Citation2014) will help the student understand where they have come from, where they are, and how they might balance action and reflection, support and challenge. In the absence of an electronic health record system, this will remain a problem unless some protocol is agreed for a consistent method of filing results. In examining the synergies between AL and QI, highlights the key characteristics of both ().

Table 2. Synergies between AL and QI.

While moving from face-to-face ALS to virtual ALS was a challenge during the pandemic, the use of breakout rooms in Blackboard Collaborate, the online platform, worked well. Although virtual action learning (VAL) has been reported in the literature since the 1990s (Gray Citation2001; Dickenson, Burgoyne, and Pedler Citation2010), the pandemic forced some of us to develop competencies with this format, having not tried it previously. Although the Blackboard Collaborate platform was new for students we had quickly trained them up to use the system, including breakout rooms. Some of the groups had already started ALS face-to-face and saw the benefits of the meetings (Edmonstone Citation2015). With the increased use of telemedicine during the pandemic the VAL format was seen to give the students the experience of asking questions online, in readiness for virtual patient consultations. However, one study (Sorensen et al. Citation2020) showed that preferences for virtual visits decreased with increasing complexity of the surgical intervention, even during the pandemic, and most respondents believed that establishing trust was best accomplished in person. In addition, the majority of patients believed it was important to meet their surgeons in person, before the day of surgery.

While the challenges of VAL include the willingness of the educator to give it a try (Willis, Prass, and Karstadt Citation2017) I found that, as a facilitator, working with small groups of students, my presence in the breakout room did seem to hinder the AL process. This may have been that my presence seemed closer online, than being in a physical room where I try to keep a distance from the ALS, while still hearing the questioning approach used as well as noting the active listening, note taking, etc.

Discussion

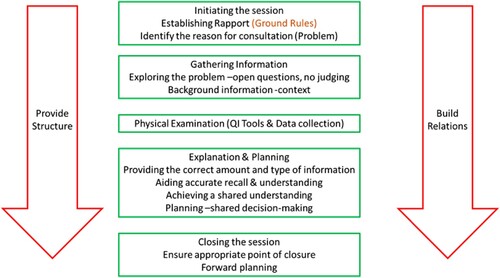

At the heart of AL and the process of QI is communication, a universally recognised, essential skill for medicine. Communication skills training in the past, was generally gained from the clinical experience of practicing doctors in their encounters with patients (Kurtz and Silverman Citation1996). According to Kurtz et al. (Citation2003), medical students confront two different models of the medical interview; a communication model dealing with the process of the interview, and the traditional medical history, dealing with the content of the interview. The authors developed their Calgary Cambridge model further to more closely align the medical interview with the structure and process skills used in communication skills training (). Furthermore, the patient’s perspective of their illness was added to the medical history so as not to focus entirely on the biomedical model of disease. Studies of patient satisfaction and adherence to treatment confirm the need for a broader view of history taking that encompasses content from the patient’s life-world, as well as the doctor’s more limited biological perspective (Noordman et al. Citation2019; Buawangpong et al. Citation2020; Steinmair et al. Citation2022).

Figure 1. Calgary Cambridge Model amended (Kurtz et al., Citation2003).

I believe that the Calgary Cambridge model closely aligns with AL in providing structure and building relations with team members. When initiating the session and establishing rapport, ground rules are generally agreed which include protected time to present the problem, no interruptions and no judgements (). These ground rules, while not explicit in the patient consultation are important for establishing trust in the communication event. This format fits ALand medical consultations. It necessitates active listening; requiring doctors to remove distractions, observing non-verbal communication feeding back what they have understood, and providing a safe environment. Exploring the problem further will require detailed background information and context. For PAs, context provides a holistic assessment to include social and family history. For AL and QI projects, context will help get to the root cause of the problem as the emphasis is on the process flow of the problem being investigated.

Reflections and conclusion

While AL was set up as a teaching/learning method to provide supervision for PA students undertaking QI projects, it undoubtedly reinforces communication skills training which the students commenced at the beginning of their programme. It was only on close inspection of the AL process in the context of transferable skills for the student’s role as a PA did the connections between AL and communication skills training, using the Calgary Cambridge model come to light. In setting out on this journey, the synergies between AL and QI were forefront in my mind but now the synergies between all three seem obvious. Whether the consultation is for medical reasons or to work on a QI project a key requirement is trust. Taking time to establish rapport and develop trust is paramount whether the communication involves a medical decision or a QI process issue. While trust can be regarded as a pre-requisite for success in putting ideas forward in ALS (Olsson et al. Citation2010) so too is trust a core foundation of taking a patient-centred approach in medical consultations, increasing the likelihood of patient willingness to follow treatment plans (Brand and van Dulmen Citation2017). While traditional hierarchies and structures in healthcare continue to create barriers to effective interprofessional collaboration, early experiences with other healthcare professions can help breakdown these barriers (Arnold et al. Citation2020). Using ALin medicine can further re-enforce the importance of communication skills training with open questions, reflection, non-judgemental approach and taking one’s time to reach a solution/diagnosis. Due to new insights gained I now use the Calgary Cambridge model of communication as my starting point to introduce action learning, connecting with a framework which students are already familiar with, therefore scaffolding their learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pauline Joyce

Dr. Pauline Joyce is a Director of Quality & Clinical Engagement, MSc Physician Associate Studies, at the RCSI, Dublin Ireland. She managed a pilot project with the Irish Department of Health to introduce the Physician Associate role in Ireland. She has experience in the facilitation of action learning, in postgraduate programmes, over the past 15 years and has worked in an academic institution for 20 years. She holds an EdD (Education & Leadership) and an MSc in Education & Training Management from DCU. Pauline’s research experience include action research and more recently quality improvement as part of implementation science.

References

- Arnold, C., S. Berger, N. Gronewold, D. Schwabe, B. Götsch, C. Mahler, and J.-H. Schultz. 2020. “Exploring Early Interprofessional Socialization: A Pilot Study of Student’s Experiences in Medical History Taking.” Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–8. doi:10.1080/13561820.2019.1708872.

- Batalden, P., and F. Davidoff. 2007. “Teaching Quality ImprovementThe Devil is in the Details.” JAMA 298 (9): 1059–1061. doi:10.1001/jama.298.9.1059.

- Berkowitz, O., C. Goldgar, S. E. White, and M. L. Warner. 2019. “A National Survey of Quality Improvement Education in Physician Assistant Programs.” The Journal of Physician Assistant Education 30 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1097/JPA.0000000000000243.

- Berkowitz, O., S. White, C. Goldgar, M. Brisotti, and M. Warner. 2014. “Defining Quality Improvement Education for Physician Assistants.” The Journal of Physician Assistant Education: The Official Journal of the Physician Assistant Education Association 25: 55–60. doi:10.1097/01367895-201425040-00010.

- Brand, P. L. P., and S. van Dulmen. 2017. “Can We Trust What Parents Tell Us? A Systematic Review.” Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 24: 65–71. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2017.01.003.

- Brook, C. 2010. “The Role of the NHS in the Development of Revans’ Action Learning: Correspondence and Contradiction in Action Learning Development and Practice.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (2): 181–192. doi:10.1080/14767333.2010.488329.

- Buawangpong, N., K. Pinyopornpanish, W. Jiraporncharoen, N. Dejkriengkraikul, P. Sagulkoo, C. Pateekhum, and C. Angkurawaranon. 2020. “Incorporating the Patient-Centered Approach into Clinical Practice Helps Improve Quality of Care in Cases of Hypertension: A Retrospective Cohort Study.” BMC Family Practice 21 (1): 108. doi:10.1186/s12875-020-01183-0.

- Dickenson, M., J. Burgoyne, and M. Pedler. 2010. “Virtual Action Learning: Practices and Challenges.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1080/14767330903576978.

- Edmonstone, J. 2014. “On the Nature of Problems in Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 11 (1): 25–41. doi:10.1080/14767333.2013.870879.

- Edmonstone, J. 2015. “The Challenge of Evaluating Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 12 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1080/14767333.2015.1041452.

- Gray, D. 2001. “Work-based Learning, Action Learning and the Virtual Paradigm.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 25 (3): 315–324. doi:10.1080/03098770120077676.

- Gualandi, R., C. Masella, D. Viglione, and D. Tartaglini. 2019. “Exploring the Hospital Patient Journey: What Does the Patient Experience?” PLOS ONE 14 (12): e0224899. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224899.

- HSE. 2019. National Review of Clinical Audit. Accessed 03/06/22. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/national-review-of-clinical-audit-report-2019.pdf.

- Improta, G., G. Balato, C. Ricciardi, M. A. Russo, I. Santalucia, M. Triassi, and M. Cesarelli. 2019. “Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare: Fast Track Surgery for Patients Undergoing Prosthetic hip Replacement Surgery.” The TQM Journal 31 (4): 526–540. doi:10.1108/TQM-10-2018-0142.

- Institute of Medicine & Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. 2000. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Joyce, P. 2012. “Action Learning – A Process Which Supports Organisational Change Initiatives.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 9 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/14767333.2012.656888.

- Joyce, P., R. S. Hooker, D. Woodmansee, and A. D. Hill. 2019. “Introducing the Physician Associate Role in Ireland: Evaluation of a Hospital Based Pilot Project.” Journal of Hospital Administration 8 (3): 50. doi:10.5430/jha.v8n3p50.

- Kindratt, T. B., and V. L. Orcutt. 2017. “Development of a Quality Improvement Curriculum in Physician Assistant Studies.” The Journal of Physician Assistant Education 28 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1097/JPA.0000000000000115.

- Kurtz, S. M., and J. D. Silverman. 1996. “The Calgary—Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An aid to Defining the Curriculum and Organizing the Teaching in Communication Training Programmes.” Medical Education 30 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00724.x.

- Kurtz, S., J. Silverman, J. Benson, and J. Draper. 2003. “Marrying Content and Process in Clinical Method Teaching: Enhancing the Calgary–Cambridge Guides.” Academic Medicine 78 (8): 802–809.

- Mathews, S., S. Golden, R. Demski, P. Pronovost, and L. Ishii. 2017. “Advancing Health Care Quality and Safety Through Action Learning.” Leadership in Health Services 30 (2): 148–158. doi:10.1108/LHS-10-2016-0051.

- McCarthy, S. E., S. B. Jabakhanji, J. Martin, M. A. Flynn, and J. Sørensen. 2021. “Reporting Standards, Outcomes and Costs of Quality Improvement Studies in Ireland: A Scoping Review.” BMJ Open Quality 10 (3): e001319. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001319.

- Noordman, J., B. Post, A. A. M. van Dartel, J. M. A. Slits, and T. C. olde Hartman. 2019. “Training Residents in Patient-Centred Communication and Empathy: Evaluation from Patients, Observers and Residents.” BMC Medical Education 19 (1): 128. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1555-5.

- Olsson, A., C. Wadell, P. Odenrick, and M. N. Bergendahl. 2010. “An Action Learning Method for Increased Innovation Capability in Organisations.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (2): 167–179. doi:10.1080/14767333.2010.488328.

- Pedler, M., and K. Trehan. 2008. “Action Learning, Organisational Research and the ‘Wicked’ Problems.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 5 (3): 203–205. doi:10.1080/14767330802461181.

- Sorensen, M. J., S. Bessen, J. Danford, C. Fleischer, and S. L. Wong. 2020. “Telemedicine for Surgical Consultations – Pandemic Response or Here to Stay?” Annals of Surgery 272 (3): e174–e180. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004125.

- Steinmair, D., K. Zervos, G. Wong, and H. Löffler-Stastka. 2022. “Importance of Communication in Medical Practice and Medical Education: An Emphasis on Empathy and Attitudes and Their Possible Influences.” World Journal of Psychiatry 12 (2): 323–337. doi:10.5498/wjp.v12.i2.323.

- Willis, S., N. Prass, and L. Karstadt. 2017. “Appropriateness of Action Learning in the Physical and Virtual Spaces: A Discussion.” Journal of Paramedic Practice 9 (5): 196–200. doi:10.12968/jpar.2017.9.5.196.