ABSTRACT

Police forces in England and Wales have faced ongoing difficulties of engagement with minority communities leading to a loss of confidence and trust in policing. The paper reports on the results of a project to improve relations with communities with Humberside Police, UK by implementing key ideas relating to procedural justice that consider how fairness in interactions between the police and others can promote the perception of police legitimacy. An Action Learning Research project was set up during the Covid Pandemic to apply procedural justice. Two groups of front line officers worked with a researcher/facilitator over five meetings with the support of senior officers. Data provided from the meetings and written logs were analysed to show how procedural justice works towards relationship development and more positive opinion of the police in interactions. It is suggested that police forces can tackle difficult issues such as engagement with communities by more use of action learning research in collaboration with researchers.

Introduction

Police forces in England and Wales and beyond face considerable challenges in adopting policies and practices of Diversity and Inclusion, both within their organisations and the policing of their communities. Crucial to the latter is the key principle of policing by consent which requires engagement that is transparent and ethical and a workforce that is a reflection of the communities they serve. As the founder of the police service, Sir Robert Peel stated that the ‘Police are the public and the public are the police’. However, the Lammy Review (Citation2017) which considered the treatment of, and outcomes for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) individuals in the criminal justice system, found a significant proportionate rise in offending, reoffending and youth prisoners over 10 years. Most recently, during the Covid pandemic, it has been found that disproportionate measures such fines and stop and search are more likely to be applied to BAME citizens, sometimes significantly so.Footnote1 Williams (HMICFRS Citation2021), argued that during the Covid pandemic, that with respect to drug enforcement, such searches often found nothing but disproportionality damaged relations with communities. An inquiry by the Home Affairs Select Committee in July 2021Footnote2 which considered progress since the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry (Macpherson Citation1999), found ‘a significant problem with confidence in the police within Black communities, particularly among young people’. A recent systematic review of evidence from different countries by Carvalho, Mizael, and Sampaio (Citation2021) found that Black men in particular were subject to stops by the Police which in turn resulted in negative perceptions of the Police.

The aim of this paper is to report on the results of a project to improve relations with communities with Humberside Police, UK by implementing key ideas relating to procedural justice (Tyler Citation1990). The project provides an example of the use of Action Learning Research (ALR) involving front line police officers working and learning with the ideas in action learning sets who agreed to provide data to a researcher on their experiences and learning. Therefore the research question is: Using Action Learning Research, How can working with procedural justice improve police relations with communities? We begin with a brief overview of the key difficulties with particular reference to policing diverse communities before considering the meaning of and evidence relating to procedural justice. The paper then provides an exploration of an intervention based on ALR to work with procedural justice.

Policing and communities

In the UK, there have been significant concerns on representation and relationships of the police with Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) and other communities. For example, both the Scarman Report (Scarman Citation1981) and the Macpherson Report (Macpherson Citation1999) can be seen as crucial turning points in how the police needed to consider these issues. In particular, the Macpherson Report highlighted how policing could be considered as ‘institutionally racist’ and this term has affected responses across the world as well as providing background for contention and debate (Bartkowiak-Théron and Asquith Citation2015).

The Macpherson Report (Citation1999) defined institutional racism as a ‘collective failure of an organisations to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin’ (para 6.34). As a consequence, the behaviour and attitudes of people within the organisation can discriminate and sterotype minority ethnic people through ‘unwitting prejudice’. Following the report, it became evident that incidents of overt racism within police forces began to subside. However attention turned to covert racism which had been identified in Macpherson although more difficult to identify except if incidents affected BAME and other groups in a negative or different way. Thus obvious examples of racist behaviour might be subject to disciplinary procedures, a great deal of police work occurs in closed and specialised space which can hide racist behaviour and language (Holdaway and O’Neill Citation2007).Footnote3 One issue apparent with respect to institutional racism is that by focussing on race other forms of discrimination such as homophobia and disability might be neglected. Further research suggests that much effort has focussed on internal police culture and a decline in overt racist language but may miss deeply embedded and structural features of everyday practices (Souhami Citation2014). The Sewell Report (CRED Citation2021) suggested that the term ‘BAME’ had been unhelpful and that it would be better to focus on disparities for specific ethnic groups. The report was also critical of the term ‘institutional racism’ when used as a general ‘catch-all’ phrase rather than when proven as ‘deep-seated racism on a systemic level’ (9).Footnote4

All police officers and members of police staff are drawn from a variety of communities. Therefore, they carry into their work the values and belief set that can feed particular preferences in particular situations. Such preferences can include biases and prejudices that are based on gender, race, sexual orientation, or other facets of identity. Further, such values and beliefs may be held unconsciously or implicitly, even where claims are made for no preferences or unbiased views. Lack of awareness of such view can result in negative stereotyping of particular groups based on race, ethnicity or other characteristics and this has been of concern in police behaviour and the working of the criminal justice system. Recent years have seen a transformation of stereotypes relating to Asians/Muslims in the context of the ‘war on terror’, for example (Awan Citation2018). Research by Minhas and Walsh (Citation2018) found that decision-making by police investigations tended be affected by negative stereotypes. Extending their study to what happened in interviews by the police, legal representatives perceived that guilt and bias were based on stereotyping of their clients (Minhas and Walsh Citation2021). There are also concerns that, based on stereotyping and stigmatisation, some policing may be tainted by dehumanisation of minority groups and others where there is a degree of denial of their humanity (Savage Citation2013). This can provide some explanation of disproportional enforcement and arrests for certain minority groups (Bustamante, Jashnani, and Stoudt Citation2019).

Police forces have attempted to help their officers become aware of bias to reduce reliance on stereotypes through training. Such training can include education on the impact of unconscious bias, practice of bias reduction strategies and completion of tests such as the Implicit Assumptions Test (IAT) to reveal the presence of bias (EHRC Citation2018). Such training can improve knowledge, create awareness of attitudes and reform intentions to behave but not necessarily affect how they actually behave in interactions with the public (Miller et al. Citation2020). This suggests that training programmes alone cannot be enough to tackle such difficult and embedded issues such as unconscious bias which is most likely be evidenced covertly in everyday interactions within police forces and with communities. If attention shifts to such interactions, this suggests that action learning could be a more appropriate intervention.

Engagement with different communities is a difficult problem for police forces and given its longevity and contested nature as an issue, might be better portrayed as a wicked or intractable problem (West Churchman Citation1967) which does not have an obvious solution. Faced with the complexity of engagement with different communities during a time of social disturbance both during and beyond the Covid pandemic, police forces need to explore new possibilities and give less energy to actions that have not succeeded. This supports the idea of what Brook et al. (Citation2016) refer to as ‘unlearning’ where what police officers do in their interactions can be questioned and reconsidered to allow new possibilities to emerge. Further, unlearning needs the support of a social process such as action learning, in particular an approach such as Critical Action Learning or CAL that allows assumptions that underpin beliefs to be critiqued and associated emotions to be considered (Trehan and Rigg Citation2015). However, unlearning need not mean the rejection of evidence or ideas that could work and, with respect to engagement with communities, such possibilities are provided by the concept of procedural justice.

Procedural justice

The theory of procedural justice (Tyler Citation1990) is concerned with the treatment of people in their interactions with authority figures such as the police. Whether people consider their treatment as fair and reasonable will affect whether they consider the police as legitimate (Nivette, Eisner, and Ribeaud Citation2020). Further people can experience treatment directly or by learning from others who tell stories of their own treatment and this can feed into generalised notions relating to the law and those that enforce it (Tyler Citation2003).

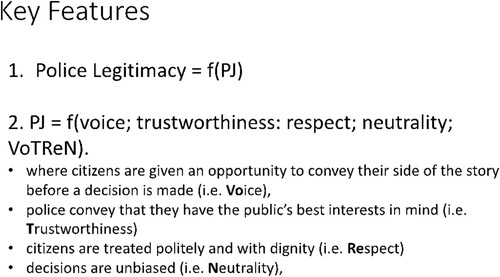

According to Tyler, the key features of fairness in interactions with the police and the outcomes are:

Voice – the chance to give their side of the story

Respect – treatment is polite and dignified

Neutrality – decisions are unbiased

Trustworthiness – the police show their interest for the public and community

Notwithstanding the fact that police officers often face interactions that carry threat and danger, it has to be recognised that working with procedural justice can be problematic. If police officers are, in the face of difficulty, required to use physical enforcement, the way such interactions are policed can still be informed by procedural justice (Worden and McLean Citation2017a). Social and historical context can have an impact on any interactions and there can be different perceptions and interpretations of how procedural justice is working against the recognition of legitimacy (Worden and McLean Citation2017b). For example, during the Covid pandemic perceptions of procedural justice have been affected by the police wearing personal protective equipment including face masks and medical gloves (Sandrin and Simpson Citation2022). The years of the pandemic, starting in 2020 when countries such as the UK passed legislation to protect public safety, required police forces to ensure compliance with measures. This presented a challenge to the police with respect to perceptions of legitimacy, requiring adoption of a procedurally just approach (Farrow Citation2020).

Police interactions with the public will be increasingly affected by the use of predictive analytics where particular crimes and/or the criminality of individuals is based on data sets that form algorithms (Baraniuk Citation2015). Since such data sets may contain seeds from the past that reinforce stereotypes and activities that are focused on particular groups, there is concern that algorithms learn to continue to target minority communities (Brantingham, Valasik, and Mohler Citation2018). Nagtegaal (Citation2021) suggests that where practices for the police are determined by algorithms, procedural justice perceptions are more positive for less complex practices. However, an over-reliance on predictions at the expense of understanding complex and dynamic factors at work (Babuta Citation2017) can result in an adverse perception of procedural justice.

It is interesting to note that the Sewell Report (CRED Citation2021), completed in response to issues relating to Black Lives Matter, proved to be contentious and controversial. However, the report focused on building trust with specific recommendations relating to legitimacy and accountability. Further, there was concern that more attention should be given to disparities with specific ethnic groups to gain greater understanding. Such concepts are central to procedural justice. In addition, as the HMICFRS (Citation2021) report identified, police officers in their interactions with the public and different communities needed to build rapport and prevent escalation.

In summary, there have been long-standing concerns relating to the policing of diverse communities in England and Wales. In particular various reports and research have highlighted the need to restore trust with communities. The concept of procedural justice is concerned with how interactions between authority groups such as the police and members of different communities can create the perceptions of fairness and improve the legitimacy of the police. Further, persistent application of procedural justice has been shown by research to improve perceptions of legitimacy even among people who are antagonistic towards the police.

Background to the project and method

In this section, we consider the background to the police force where a project to apply procedural justice through ALR was completed during 2020/2021. We explain how the project was designed, the theoretical underpinning and a methodology based on Revans’ (Citation1971) theory of action.

This project took place in the Humberside Police Service (HPS), one of 43 police forces in England and Wales, with separate forces in Scotland, Northern Ireland and a British Transport Police. HPS provides policing services for East Yorkshire and northern Lincolnshire and consists of approximately 3000 uniformed officers and staff. Along with other forces, HPS has developed its own strategy and plan for Diversity and Inclusion in response to the direction set by the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC Citation2018). The plan declares how HPS will ‘provide a professional policing service to our communities to make them safer and stronger’.

As a way of responding to this plan, the issue of engaging with communities was identified as one that needed particular attention. Like other police forces in England and Wales, HPS had suffered from a fall in levels of trust from different communities which posed a threat to their legitimacy. As part of our relationship with HPS, we were able to suggest an application of procedural justice by working with action learning but also allowing a collaborative process of research to be undertaken. This made the process an example of action learning research (ALR), a learner-oriented process that also allows collaboration for the emergence of local actionable knowledge (Raelin Citation2015). ALR is an approach to research which is action-oriented and which contributes to both practice in terms of improvement in issues of concern and to the creation of knowledge which could be used by others. Such knowledge emerges from action in particular situations. It, therefore, is based on data that is rooted in a context and meaningful in that context but with potential for use In other contexts (Coghlan and Coughlan Citation2010).

Since the application of procedural justice would require police officers to hold a range of conversations both with the public, each other and researchers, to capture meanings made in such conversations, our approach was informed by social constructionism. In particular, we considered how meanings were made within a relational nucleus between two or more others (Gergen Citation1995). The central feature of procedural justice is interactions between officers and others to construct accepted meanings by both participants. However, attempts by officers to apply procedural justice in interactions cannot be assured, their words have the potential for accepted meaning but require a positive response from others and for the relationship to continue; a failure to gain such responses can reduce their efforts to ‘nonsense’ (37).

According to Coghlan and Coughlan (Citation2010), the methodology of ALR is based on Revans’ theory of action and the cyclical systems of Systems Alpha, Beta and Gamma (Revans Citation1971). For System Alpha, the investigation of the problem of engagement with communities was completed with senior officers to ensure acceptance of the value of the project and appropriate support for resourcing, System Beta allowed the operational understanding of procedural justice and ongoing development of learning resources and responses to issues as they emerged. System Gamma ensured that the learning by officers was central to the project, allowing them as participants to reflect on their experience of applying procedural justice and to raise questions as they proceeded.

The projected unfolded as follows. Firstly, with the approval and support of the Deputy Chief Constable, three senior officers – a Chief Superintendent, a Chief Inspector and Inspector – worked with the researcher to consider the issue of engagement with communities as a complex and difficult problem. This was followed by questions raised by their diagnosis to consider how procedural justice could be applied by front line officers in their interactions. This led to the formation of two action learning groups of front line officer in two districts of HPS with an agreement to make a record of actions using written logs which could be shared and used for research. This use of written logs would serve a dual purpose of firstly and primarily, allowing officers to reflect on and critique their experiences of interactions and secondly, share their findings with the researcher.

The two districts were selected by the Chief Inspector on the basis of his knowledge of the communities present in each district and the support for a project from Inspectors in those districts. Each ALR group consisted of four front line officers, chosen by an Inspector and supported by a sergeant who also attended group meetings along with the researcher. All the officers were of equal rank. The presence of a sergeant at reviews was a feature of how support for the project was provided and how value for others could be assessed (Brunetto and Farr-Wharton Citation2003).

The researcher was able collect data at each stage, facilitate the unfolding of the project and interpret results for presentation to all participants as well as disseminate findings to others. While officer interactions to apply the ideas of procedural justice took place in various locations in ‘real life’, the interactions with the researcher were designed to capture contextualised versions of reality that would enable the development of new possibilities for action. Since the project took place during the Covid pandemic, we worked with ALR virtually, mediated by the use of appropriate technology to create a form of Virtual Action Learning (Dickenson, Burgoyne, and Pedler Citation2010).

Findings

Engagement and relationships with minority groups in the community is understood as a difficult issue in policing. On 30 August 2020, The Guardian published an article entitled, ‘George Floyd-style killing could happen in the UK’, which reported on the concerns of a former Chief Constable – Michael Fuller – who pointed to the disproportionate numbers of black people who were in the criminal justice system, especially those in prison. This was creating a sense of alienation by the community.Footnote6 Accepting the difficulty and deep-seated nature of this issue, three senior officers in HPS – a Chief Superintendent, a Chief Inspector and Inspector – agreed to complete a cognitive map (Aniyar Citation2019) to consider the issue of ‘communities not engaging’. Mapping served to provide an opportunity to investigate the problem as a System Alpha cycle. Revans (Citation1971) saw System Alpha as concerned with using ‘information for DESIGNING objectives’ (33, emphasis in the original) and while formal objectives were not set, the mapping of key concepts as alternative poles of constructs allow more desirable possibilities come into view.

A part of the map is shown in .

The completion of the map which surfaced terms such as trust, visibility, listen and meeting allowed the suggestion of the use of action learning and working with procedural justice. This provided the authority for the project and the formation of two ALR groups each supported by a sergeant as the first line manager for front line officers (Butterfield, Edwards, and Woodall Citation2004). Each group was selected by an inspector in particular areas of Humberside chosen by the Chief Inspector on the basis of his knowledge of the communities present. There were four front-line officers in each group supported by their sergeant, who could arrange meetings with the researcher according to the shift patterns of the officers. Because officers were selected on the basis of their interest and relationship with communities, there was high attendance at all the meeting with absences due to policing contingencies. However, contact could maintained by email if required. Meetings were held every four weeks and there were five meetings for each group lasting between 30 and 45 minutes.

At the first virtual meetings in February 2021, a briefing and introduction to procedural justice was provided and the process of action learning. Each officer had experience of working and interacting with members of diverse communities in Humberside. An emphasis was placed applying procedural justice where they could but consistently if possible, justified by the research evidence (Madon, Murphy, and Sargeant Citation2017). The key features of procedural justice were presented as shown in .

The initial focus was Voice, allowing people to give their side of the story once a stable interaction was possible; it was essential the officers used their discretion and recognised their vital contribution to problem-solving in the community (Glaser and Denhardt Citation2010). Where possible, officers were asked to record in learning logs what happened and what they learned as shown in .

Table 1. A learning log for procedural justice.

At the first review, the learning from logs were shared with each officer, the sergeant and the researcher. It was clear, that while implementation was mainly ‘common sense’, setting it in the context of applying a theory based on evidence was valuable and their actions had results that were important. For the next phase, officers were asked to add Respect to Voice through dignified and polite treatment. We could subsequently extend the process to consider Trustworthiness and Neutrality in decision-making.

Over 4 months a total of 18 logs were recorded and sent to others and the researchers. Officers found the completion of logs interesting but not always easy to write in the context of front-line policing, Nevertheless, sufficient logs were completed by all officers and provided data for further analysis and potentially knowledge for action. Logs recorded a wide variety of interactions with individuals and groups including those relating to domestic abuse, missing persons, problems with care, harassment and suspicion of carrying drugs. We did not ask for specification of community categorisation. Thematic analysis was used for coding and then development of themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in accordance with the social constructionist underpinning of the project. The analysis had the potential of revealing officer experience of applying procedural justice in everyday interactions and the production of knowledge to share with others. Importantly, the ALR processes allowed ongoing understanding of how procedural justice, or ‘PJ’ as we called it, in accordance with System Beta cycles. As shown below this also included an occasion where PJ could not be applied. The officers were informed that they could contact the researcher at any time by posing questions relating to PJ or when PJ could not be applied. The use of learning logs with space to record a reflective account of what happened ensured that learning by the officers was at the core of the project – System Gamma – but sharing with others also allowed a reconnection to considering PJ and the purpose of the project – Systems Beta and Alpha.

The analysis revealed six themes following the coding of officer learning logs. The themes were:

Listening

Standing Back

Understanding

Relationship Development

Positive opinion of the police

Results

Each theme is now considered based on comments presented in the logs.

Interestingly, the first theme that appeared corresponded to a key point made in the diagnosis shown in – listening. Further the project emphasised interaction with members of different communities so listening was happening in meetings. It was recognised that ‘Nothing beats face to face contact and a smile’. Officers recorded that ‘lack of listening’ was often a problem in interactions with the police and that it was ‘difficult to engage in listening, when their agenda doesn’t match up with your own’. By giving an opportunity to ‘listen to concerns’, ‘hear their wishes’, ‘rant to get her emotions out’ and ‘be taken seriously’ officers were provided with a chance to ‘gain a better understanding’ and ‘then get better results’. One officer made the link between listening and building trust:

taking extra time to ensure a victim feels they are being listened to and taken seriously it can build trust in police.

..showing active listening in my body language and when she became teary again I told her ‘TAKE A BREATH, YOU'RE DOING OKAY. I KNOW THIS IS AN UPSETTING SITUATION, AND I APPRECIATE YOU ARE CONCERNED ABOUT YOUR KIDS. (emphasis in the original)

Understanding has implications for two other themes that could be identified – relationship-building and positive opinion of the police. The process of listening to allow understanding was considered crucial to ‘building up a good working relationship’ and this was associated with ‘building trust’. For one officer, communication became more ‘effective’ and this was more ‘suited to their way of thinking’ – a discovery that ‘still amazes me’. Within this process, officers could ‘find alternative methods that can change pre-existing conceptions some members of the public have towards the police’ and potentially ‘completely change the course of incidents’. The ‘clarification of the situation’ obtained from listening and understanding ‘negated the need for an arrest’ and ‘did not leave this female having a negative and tarnished opinion on the Police force’.

In most cases, the officers could point to more positive results as another theme. This included the avoidance of ‘arrest’ but also the provision of ‘sufficient evidence to charge the suspect with the offences’. Officers could gather ‘full details’ which allowed ‘best resources’ to be ‘put in place’. There was recognition that ‘the same outcome’ was achieved with a more informed approach. A victim ‘felt much happier’ and could be offered access to more ‘support that she needed’. On one occasion the result was simply to allow someone to ‘calm down faster (rather than telling her to calm down)’ and ‘finding an agreed course of action with our policing framework’ thus ‘saving resources’. By ‘allowing a person to be part of the decision making process’, the officer felt this became ‘empowering for them’.

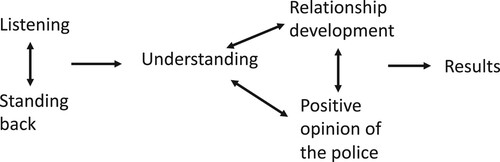

Based on the themes that emerged from the logs, it becomes possible to consider how procedural justice, which Madon, Murphy, and Sargeant (Citation2017) suggested needed to be ‘at front of mind’ (638) in interactions, can help restore trust in the police, even in difficult situations. For example, how listening and understanding provide the basis for an officer’s behaviour which affects the response of others, the development of relationship and the opinions of police work. shows a possible model for how procedural justice can affect results achieved in police work with different communities.

Drawn from the findings contained in officers’ logs, the model has key inputs to enact procedural justice in interactions with different communities. It begins with listening and a stance of standing back, meaning an avoidance where possible of immediate enforcement. Of course, this is not always possible and officers in this project were always briefed to work with procedural justice when they felt safe enough to do so. If officers listen and stand back, they hear the voices of others, who can give their stories and, accompanied by a demeanour to show respect, which allows understanding to occur. There then follows a dynamic between understanding, relationship development and positive opinion of the police by others who value the approach which provides evidence that the police can be trusted, and positive results can be achieved.

While most of the logs reported how applying the idea of procedural justice could lead to positive result, one log in particular showed that everyday life is less predictable. The log reported an incident involving stopping a car whose occupants, based on intelligence received, were known to be involved in the supply of drugs – they were ‘nominals linked to OCGs’ or organised crime gangs. While officers tried to listen and show respect, this was met with disrespect and the possibility of physical resistance. We discussed the issue as part of the learning process and this prompted a question: Can we use PJ when people disrespect the Police? This led to a search for any ideas from research to provide guidance for future action or Programmed Instruction (P) in action learning terms (Revans Citation1998). Reisig et al. (Citation2004) considered disrespect towards the police with a suggestion that image and identity protection are often working in disrespect and that interactions take place in a neighbourhood which can influence events. The officer responded by saying:

… .whilst we would never have won this guy over, it would have made us look even better on our body worn footage if it showed us being incredibly respectful … …

Discussion

On 13 June 2020, the local paper in Humberside ran a headline stating ‘Humberside Police more likely to use force against black people’.Footnote7 This was a reflection from across the world of the difficulties of engaging with communities, heightened by events in the US that resulted in protests under the heading of Black Lives Matter. HPS, in line with its strategy for Diversity and Inclusion, with the support of senior managers, provided a willingness to set the issue of engagement with communities as an important and real problem. This consideration as System Alpha allowed the ALR project to emerge in collaboration with the researcher.

presented in this paper is tentative model for action created through the research from the practice of police officers in particular situations in districts within Humberside, UK. It is therefore context dependent and subject meanings made by those involved. However, it does provide some important indications of what can help officers in HPS and perhaps elsewhere of how they can approach and improve interactions in pursuit of procedural justice. Perhaps the primary skills identified are those of listening and standing back, both identified as interpersonal skills that might not have sufficient focus in the training of police offices (McDermott and Hulse Citation2012). Listening is seen as crucial to how an officer can communicate with others and lack of listening can also set a limit on an officer’s use of their technical abilities. By listening an officer gains crucial information that leads to better understanding. Further, research suggests that listening in combination with observing visual cues can provide a counter to the potential for a low accuracy rate and bias towards believing that people lie when an officer relies on observation alone (Mann et al. Citation2008). When listening is combined with standing back, it allows a form of what Schön (Citation1987) called ‘reflection-in-action’ (4) which allows the possibility to solve new problems and to ‘change the situation for the better’. Indeed an officer could generate new insights and uncover new ways of responding in the context of practice, as evidenced by some of the log reports. Officers who can adopt listening and standing back, allowing them to reflect on what is happening, are also learning to become what Schön referred to as reflective practitioners who are able to cope with contradiction, ambiguity and change.

Standing back can also prevent officers from rushing to decisions which could potentially reinforce initial impressions, based on implicit bias. This compromises neutrality which Tyler (Citation2017) sees as crucial to avoiding bias. Standing back allows officers to assess and reassess procedures that can be considered as more appropriate to the situation they are facing before they make a decision. Empirical research has suggested that neutrality by the police is important for the improvement of perception of legitimacy and policing in general (Fine et al. Citation2022).

In , there is evidence that officers could discern improvements from the dynamic of their interactions. If listening and standing back were crucial to officer understanding, as the interactions unfolded relationships improved and officers felt the assessment of their trustworthiness was enhanced. Tyler’s (Citation2003) version of procedural justice considers trustworthiness to be concerned with how the police show their interest for the public and community. However, if we widen the meaning of trustworthiness to include perceptions of ability and integrity as well as benevolence, as considered by Shoorman, Mayer, and Davis (Citation2007), this allows a more nuanced view of how trust is working in interactions. Crucially, it also allows for a degree of reciprocity between participants in an interaction, although it needs to recognised that police officers do have a degree of power which is reinforced by a social, historical and institutional context. However, the consent that police officers in the UK have traditionally enjoyed has also created assumptions of its continuation over a time period of significant changes which require a reshaping of police roles and beliefs (Schaap Citation2021). Perhaps a key feature of reshaping is an exploration of the meaning of consent? The word itself can be traced to two Latin words – ‘con’ meaning together and ‘sentire’ meaning feel which interestingly also covers senses such as hearing and smelling as well as perceiving, All the evidence from the project reported in this paper was gathered from live interactions by officers seeking to apply procedural justice. Based on their evidence, recorded in the logs, we can see how on nearly all occasions, the senses were actively working in a dynamic and mostly reciprocal process to reach satisfactory results for all parties.

As an ALR project it has resulted in some key aspects for HPS on how procedural justice can be applied; can become actionable knowledge to be refined, shared and reflected upon in collaboration with other stakeholders. This would also demonstrate the potential of ALR in relation to other difficult and complex problems faced by HPS (Pedler and Trehan Citation2008). Further, as a collaboration between HPS members at different ranks and the researcher, who also acted as facilitator, the project for quality could be assessed against four criteria as presented by Shani and Coghlan (Citation2008). Firstly, the project engaged with a real life issue of engagement with communities as identified by the HPS Diversity and Inclusion strategy but also officers throughout HPS and others forces. Secondly, the project involved collaboration between the researcher and different members of HPS, who were treated as co-researchers throughout the project. Thus we have shown that after a diagnosis of the issue with senior officers, an approach based on ALR allowed line managers – the inspectors and sergeants – and front-line police officers to engage with the key features of procedural justice, record their experiences of application and declare what they were learning. Thirdly, those involved in the ALR groups were able to take action and reflect on the results of actions through learning logs but also in situations of interaction. They were able to share their learning with each other and researchers through written artefacts of learning logs. They could also enact the basic action learning equation of L = P + Q by posing questions relating to the concept of procedural justice including when the key features were more difficult to employ, e.g. when the response to respect shown by an officer was disrespect and the possibility of physical harm. Finally, the project yielded outcomes and actionable knowledge.

The programme began with actions to give voice to those they interacted with and reflecting on what happened, how they felt and what they learned. At meetings held every four weeks, the reviews of logs were shared with each other and the researchers, before moving to the features of showing respect, remaining neutral and seeking to become more trustworthy. As the logs accumulated and were shared with researchers as findings, they could be coded and developed as a form of actionable knowledge which, as argued by Coghlan and Coughlan (Citation2010) can be adapted ‘to other settings’ (202). Of course, the logs captured post interaction events in the words of officers. The words of others became available as remembered by the officers in their writing of the logs. As Schaap and Saarikkomäki (Citation2022) identify, procedural justice research does not usually consider the experiences of citizens.

The ALR approach to considering the application of procedural justice in HPS is likely to be the first of its kind in the UK and possibly elsewhere. While the concept of procedural justice has been present for several years, it is suggested that there is limited research and evidence on helping officers learn to apply the principles of procedural justice. There have been studies that show that where officers are trained in the principles, this can lead to the possibility of positive interactions with the public (Wood, Tyler, and Papachristos Citation2020). Dai (Citation2021) reports the results of a programme of procedural justice in the US of training for over 500 police officers which included a survey of over 200 citizen perceptions relating to their interactions with police which were generally positive. Evaluation of training reported has been mostly quantitative relying on large numbers of responses to various survey instruments. In common with much research on procedural justice, quantitative approaches to data collection lend themselves to statistical modelling but as argued by Schaap and Saarikkomäki (Citation2022), this can create difficulties with respect to the direction of causality between key concepts based on correlation coefficients. It also becomes difficult to make distinctions between processes and outcomes in interactions between the police and communities. By contrast, qualitative approaches to research and, we would argue, an ALR project to apply procedural justice can give more attention to everyday experiences of what happens in interactions leading to contextualised outcomes and actionable knowledge.

Conclusions

It seems that policing in England and Wales, in the years just before the Covid pandemic and then during, has faced a growing difficulty relating to the confidence levels of the public that they are doing a good job. This is a key indicator of how well the police is maintaining its philosophy of policing by consent (Home Office Citation2012). However, data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggested that even before the pandemic, confidence levels in the police doing a good or excellent job had fallen from 62% in 2017/2018 to 55% in 2019/2020 (ONS Citation2020). During the pandemic, these statistics were not collected and there was recognition that the police were acting reasonably by adopting an approach based on 4Es – engage, explain, encourage and enforce. Nevertheless, trust and confidence in the police was disturbed by events such as the murder of Sarah Everard by a police officer, the Stephen Port case and the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement (Mynenko and Ditcham Citation2022). There is also evidence that there has been a disproportionate targeting of minority communities who have been most harshly affected with more stops, threats of violence and false accusation of rule-breaking (Harris et al. Citation2022). These indicators suggest a need for greater consideration for working with procedural justice and what has been learnt from this project.

There is a need for police forces to reconsider the meaning of policing with consent and how officer can employ procedural justice in their interactions not just with minority groups but with all groups and individuals. As Madon, Murphy, and Sargeant (Citation2017) argue, the key features of voice, respect, trustworthiness and neutrality can lead to the police being viewed in ‘a more positive light’ and this applies where individuals might be ‘disaffected’ and ‘disengaged’ (638).

This paper has explored ongoing efforts in an English police force, HPS, to improve community engagement. At a time when police forces in England and Wales have had to complete their duties during a pandemic and after several years of financial restraint and cuts, it would not be surprise that relations with communities might suffer. It is crucial that police forces re-embrace and apply the principles of procedural justice in everyday interactions and learn from this process. One particular area of concern is the practice of stop and search, with evidence suggesting that minority ethnic communities suffer a disproportionate use of force in such interactions due to stereotyping and biased assumptions (IOPC Citation2022). This is a difficult problem for police forces but without action, it is unlikely to change; it is an aspect of policing that needs the application of procedural justice and action learning, in particular a version that allows for critique of assumptions and consideration of emotions and power – Critical Action Learning or CAL (Trehan and Rigg Citation2015).

Action learning research to apply procedural justice in the police forces needs to be considered as an alternative to broadly based training programmes, which have been shown to improve some aspects of community engagement but without providing evidence of everyday interactions and officer learning. By contrast, ALR provides an opportunity for officers to apply key ideas, seek support when there are difficulties, raise questions to access focused information or P, and learn on a continuous basis. ALR also provided data for sharing with others including researchers and the community beyond the police force, as shown in this paper. Indeed, there is a need for institutions such as the police to apply ALR to a range of complex and difficult issues that they face, working collaboratively with researchers as facilitators.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeff Gold

Jeff Gold is Professor of Organisation Learning at Leeds Beckett University. He is strong advocate of actionable approaches to research.

Notes

1 Up to date figures can be found at https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/crime-justice-and-the-law/policing/stop-and-search/latest.

2 A Summary is available at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmhaff/139/13903.htm.

3 Early in 2021, three detectives in Hampshire were dismissed from the police for their ‘homophobic, racist and sexist conversations’, captured from bugs in their office – go to https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-55586420 for more details.

4 It is worth recording that the publication of this report proved to be highly contentious. See some responses at www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-56585538.

5 In the UK, YouGov monitors public confidence in the police with recent results showing more people in the UK are unconfident rather than confident. Go to https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2021/10/06/more-britons-now-unconfident-confident-police-deal.

6 Go to https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/aug/30/george-floyd-style-killing-could-happen-in-the-uk-says-michael-fuller, accessed 31 March 2022.

7 See the full article online at https://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/news/hull-east-yorkshire-news/humberside-police-force-black-people-4203309, accessed 31 March 2022.

References

- Aniyar, D. C. 2019. “‘Paintings for a Crime’: Composed Cognitive Maps for Measuring Crime and Situation.” Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice 2 (2): 141–163.

- Awan, I. 2018. “‘I Never Did Anything Wrong’–Trojan Horse: A Qualitative Study Uncovering the Impact in Birmingham.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39: 197–211.

- Babuta, A. 2017. Big Data and Policing. London: Royal United Service Institute for Defence and Security Studies.

- Baraniuk, C. 2015. “Pre-Crime Software Recruited to Track Gang of Thieves.” New Scientist. March 11.

- Bartkowiak-Théron, I., and N. Asquith. 2015. “Policing Diversity and Vulnerability in the Post-Macpherson Era: Unintended Consequences and Missed Opportunities.” Policing 9 (1): 89–100.

- Bottoms, A., and J. Tankebe. 2012. “Beyond Procedural Justice: A Dialogic Approach to Legitimacy in Criminal Justice.” Journal of Crìminal Law and Criminology 102: 119–170.

- Brantingham, P. J., M. Valasik, and G. O. Mohler. 2018. “Does Predictive Policing Lead to Biased Arrests? Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Statistics and Public Policy 5 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brook, C., M. Pedler, C. Abbott, and J. Burgoyne. 2016. “On Stopping Doing Those Things That Are Not Getting Us to Where We Want to Be: Unlearning, Wicked Problems and Critical Action Learning.” Human Relations 69 (2): 369–389.

- Brunetto, Y., and R. Farr-Wharton. 2003. “The Commitment and Satisfaction of Lower-Ranked Police Officers: Lessons for Management.” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 26 (1): 43–63.

- Bustamante, P., G. Jashnani, and B. G. Stoudt. 2019. “Cumulative Dehumanization in Everyday Policing: The Psychological, Affective, and Material Consequences of Discretionary Arrests.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 19 (1): 305–348.

- Butterfield, R., C. E. Edwards, and J. Woodall. 2004. “The New Public Management and the UK Police Service: The Role of the Police Sergeant in the Implementation of Performance Management.” Public Management Review 6 (3): 395–415.

- Camp, N. P., R. Voigt, D. Jurafsky, and J. L. Eberhardt. 2021. “The Thin Blue Waveform: Racial Disparities in Officer Prosody Undermine Institutional Trust in the Police.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/pspa0000270.

- Carvalho, A. A. S., T. M. Mizael, and A. A. S. Sampaio. 2021. “Racial Prejudice and Police Stops: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature.” Behavior Analysis Practice, 1–18. doi:10.1007/s40617-021-00578-4.

- Coghlan, D., and P. Coughlan. 2010. “Notes toward a Philosophy of Action Learning Research.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (2): 193–203. doi:10.1080/14767333.2010.488330.

- CRED. 2021. The Report. London: Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities.

- Dai, M. 2021. “Training Police for Procedural Justice: An Evaluation of Officer Attitudes, Citizen Attitudes, and Police-Citizen Interactions.” The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles 94 (4): 481–449.

- Dickenson, M., J. Burgoyne, and M. Pedler. 2010. “Virtual Action Learning: Practices and Challenges.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (1): 59–72.

- EHRC. 2018. Unconscious Bias Training: An Assessment of the Evidence for Effectiveness. London: Equalities and Human Rights Commission.

- Farrow, K. 2020. “Policing the Pandemic in the UK Using the Principles of Procedural Justice.” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 14 (3): 587–592.

- Fine, A., J. Beardslee, R. Mays, P. Frick, L. Steinberg, and E. Cauffman. 2022. “Measuring Youths’ Perceptions of Police: Evidence from the Crossroads Study.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 28 (1): 92–107. doi:10.1037/law0000328.

- Gergen, K. J. 1995. “Relational Theory and Discourses of Power.” In Management and Organization: Relational Alternatives to Individualism, edited by D.-M. Hosking, H. P. Dachler, and K. J. Gergen, 29–50. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Glaser, M., and J. Denhardt. 2010. “Community Policing and Community Building: A Case Study of Officers Perceptions.” The American Review of Public Administration 40 (3): 309–325.

- Harris, S., R. Joseph-Salisbury, P. Williams, and L. White. 2022. “Notes on Policing, Racism and the Covid-19 Pandemic in the UK.” Race & Class 63 (3): 92–102.

- HMICFRS. 2021. Disproportionate Use Police Powers: A Spotlight on Stop and Search and the Use of Force. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services.

- Holdaway, S., and M. O’Neill. 2007. “Where Has all the Racism Gone? Views of Racism within Constabularies after Macpherson.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (3): 397–415.

- Home Office. 2012. Policing by Consent. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/policing-by-consent/definition-of-policing-by-consent.

- IOPC. 2022. National Stop and Search Learning Report. London: Independent Office of Police Complaints.

- Lammy, D. 2017. The Lammy Review: Final Report. London: Ministry of Justice.

- Macpherson, W. 1999. The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. London: Home Office.

- Madon, N., K. Murphy, and E. Sargeant. 2017. “Promoting Police Legitimacy among Disengaged Minority Groups: Does Procedural Justice Matter More?” Criminology & Criminal Justice 17: 624–642.

- Mann, S., A. Vrij, R. Fisher, and M. Robinson. 2008. “See No Lies, Hear No Lies: Differences in Discrimination Accuracy and Response Bias When Watching or Listening to Police Suspect Interviews.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 22: 1062–1071. doi:10.1002/acp.1406.

- McDermott, P., and D. Hulse. 2012. “Focus on Training: Interpersonal Skills Training in Policy Academy Curriculum. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin.” Accessed April 15, 2022. https://leb.fbi.gov/2012/february/focus-on-training-interpersonal-skills-in-police-academy-curriculum.

- Miller, J., P. Quinton, B. Alexandrou, and D. Packham. 2020. “Can Police Training Reduce Ethnic/Racial Disparities in Stop and Search? Evidence from a Multisite UK Trial.” Criminology & Public Policy 19: 1259–1287.

- Minhas, R., and D. Walsh. 2018. “Influence of Racial Stereotypes On Investigative Decision-Making In Criminal Investigations: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Cogent Social Sciences 4 (1): 538–588.

- Minhas, R., and D. Walsh. 2021. “Prejudicial Stereotyping and Police Interviewing Practices in England: An Exploration of Legal Representatives’ Perceptions.” Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 16 (3): 267–282. doi:10.1080/18335330.2021.1889016.

- Mynenko, K., and K. Ditcham. 2022. “Public Confidence in the Police: A New Low for the Service.” Accessed April 9, 2022. https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/public-confidence-police-new-low-service.

- Nagtegaal, R. 2021. “The Impact of Using Algorithms for Managerial Decisions on Public Employees’ Procedural Justice.” Government Information Quarterly 38 (1): 101536. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2020.101536.

- Nivette, A., M. Eisner, and D. Ribeaud. 2020. “Evaluating the Shared and Unique Predictors of Legal Cynicism and Police Legitimacy from Adolescence into Early Adulthood.” Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal 58: 70–100. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12230.

- NPCC. 2018. Diversity, Equality and Inclusions Strategy. London: National Police Chiefs Council.

- ONS. 2020. Crime in England and Wales: Annual Supplementary Tables. Office for National Statistics. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesannualsupplementarytables.

- Pedler, M., and K. Trehan. 2008. “Editorial. Action Learning, Organisational Research and the ‘Wicked’ Problem.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 5 (3): 203–205.

- Raelin, J. 2015. “Action Modes of Research.” In A Guide to Professional Doctorates in Business & Management, edited by L. Anderson, J. Gold, J. Stewart, and R. Thorpe, 57–76. London: Sage.

- Reisig, M. D., J. D. McCluskey, S. D. Mastrofski, and W. Terrill. 2004. “Suspect Disrespect toward the Police.” Justice Quarterly 21 (2): 241–268.

- Revans, R. W. 1971. Developing Effective Managers. London: Longman.

- Revans, R. 1998. “Sketches in Action Learning.” Performance Improvement Quarterly 11 (1): 23–27.

- Sandrin, R., and R. Simpson. 2022. “Public Assessments of Police during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Effects of Procedural Justice and Personal Protective Equipment.” Policing: An International Journal 45 (1): 154–168.

- Savage, R. 2013. “Modern Genocidal Dehumanization: A New Model.” Patterns of Prejudice 47: 139–161.

- Scarman, Lord J. 1981. The Brixton Disorders. London: HMSO.

- Schaap, D. 2021. “Police Trust-Building Strategies. A Socio-Institutional, Comparative Approach.” Policing and Society 31 (3): 304–320. doi:10.1080/10439463.2020.1726345.

- Schaap, D., and E. Saarikkomäki. 2022. “Rethinking Police Procedural Justice.” Theoretical Criminology. doi:10.1177/13624806211056680.

- Schön, D. A. 1987. “Educating the Reflective Practitioner.” Paper presented to the American Educational Research Association, Washington.

- Shani, A., and D. Coghlan. 2008. “Action Research in Business and Management: A Reflective Review.” Action Research 19 (3): 518–541.

- Shoorman, F., R. C. Mayer, and J. Davis. 2007. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust: Past, Present, and Future.” Academy of Management Review 32: 344–354. doi:10.2307/258792.

- Souhami, A. 2014. “Institutional Racism and Police Reform: An Empirical Critique.” Policing and Society 24 (1): 1–21.

- Trehan, K., and C. Rigg. 2015. “Enacting Critical Learning: Power, Politics and Emotions at Work.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (5): 791–805.

- Tyler, T. R. 1990. Why People Obey the Law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tyler, T. R. 2003. “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law.” Crime and Justice 30 (1): 283–357.

- Tyler, T. 2017. “Procedural Justice and Policing: A Rush to Judgment?” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 13: 29–53. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113318.

- West Churchman, C. 1967. “Wicked Problems.” Management Science 14 (4): B141–B142.

- Williams, W. 2021. Disproportionate Use of Police Powers. London: HM Inspector of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services.

- Wood, G., T. R. Tyler, and A. V. Papachristos. 2020. “Procedural Justice Training Reduces Police Use of Force and Complaints against Officers.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (18): 9815–9821.

- Worden, R. E., and S. J. McLean. 2017a. Mirage of Police Reform: Procedural Justice and Police Legitimacy. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Worden, R. E., and S. J. McLean. 2017b. “Research on Police Legitimacy: The State of the Art.” Policing: An International Journal 40 (3): 480–513.