ABSTRACT

The discipline of psychology has been under-represented in the critical realist account of the relationship between structure and agency. In this paper a critical realist perspective of educational psychology research focuses on the psychological analysis of the individual and what might be considered as ‘real' and having causal power. Bhaskar's criteria for an entity to be ontologically real are applied to the psychological entity of self-efficacy in the context of a typical piece of classroom teacher-pupil interaction. The role of self-efficacy alongside other psychological, social and cultural entities is presented as a causal mechanism for the generation of Archer’s internal conversation which leads to agency. Self-efficacy is further examined in relation to criteria of ontological depth and emergence. This perspective creates the basis for a consistent ontological framework across educational psychology and that of the social sciences and a sound basis for interdisciplinary research and theory development.

Introduction

The relationship between structure and agency has been the subject of intense scrutiny within critical and social realist writing (Bhaskar Citation1998, Citation2020; Archer Citation2000, Citation2003, Citation2007; Groff Citation2004; Elder-Vass Citation2007). Perspectives have derived from philosophy of science and social theory and, as a discipline, psychology has been under-represented (Pilgrim Citation2017). While aspects of mind are accorded ontologically real status in discussions of individual agency – notably Bhaskar’s (Citation1998) ‘Reasons’ and Archer’s (Citation2000, Citation2003) ‘Internal Conversation’ – little attention has been paid to the ontological status of cognitive and conative psychological constructs. On the one hand, I refer to those constructs that aim to investigate the origins of ‘reasons’ and why, in any instance, a reason which precipitates agency takes the form that it does; and on the other hand, I refer to those constructs that drive the internal conversation. It is certainly the case that a ‘common sense realist ontology’ (Maxwell Citation2012, 6) implicitly underpins much psychological research, quantitative and qualitative, together with the critical realist triad of ontological realism, epistemological relativism and judgemental rationality. However, the psychological entities within this realist ontology and which, at an epistemological level, drive psychological theory construction and explanation, have been little discussed in, for example, the context of Bhaskar's stratified and depth ontology; this is in contrast to the examination of social structures and culture undertaken by social scientists and philosophers.

A notable exception to this, however, is in relation to identity. For example, Archer (Citation2000) regards human beings to be ‘the bearers of a continuous sense of self’ (Archer Citation2000, 9) which leads to the acquisition of a personal identity. Alongside this, we develop a social identity derived from our position in society and the roles that we take up in society. Personal and social identities coexist in a dialectical relationship (Archer Citation2000, 288). However, the focus for these important conceptions of self tends to be on the relationship between agency and structure rather than on a psychological examination of, for example, the components of mind that underpin the development of personal identity. Marks and O’Mahoney (Citation2014), in a volume focused on the study of organizations, argue for a critical realist perspective in research on identity and in the course of this refer to ‘mental structures’ and emergent properties such as ‘memory, learning, imagination and reflexivity’ (74). They generate a number of questions for empirical study, some of which fall squarely within the ambit of psychology, for example, ‘How do memories, imagination, emotion, flexibility and action enable or constrain the construction of personal identity?’ (Table 4.1, 79).

It is therefore pertinent to explore how psychological constructs that further refine broad concepts such as identity and memory might be regarded from a critical realist perspective and how they meet criteria for ontological stratification and depth. It is the aim of this paper to undertake such an exploration with regard to one sub-discipline of psychology, namely psychology applied to education; and one psychological entity, namely self-efficacy, which can be considered to be a ‘lower order’ contributor to identity. The focus is on the psychological analysis of the individual and what might be considered to be ‘real’ (that is, it has causal power) as a complement to the sociological analysis of the individual which dominates the discourse on individual agency and its relation to social structure. The relevance to educational psychology derives (as in all areas where psychology is applied to real-world settings) from the fact that individual, social and cultural entities are jointly activated in the production of events in education, in particular schools and colleges. It is important that research which underpins any application of psychology has a common ontological foundation alongside other disciplines concerned with the specific areas of application; it is imperative that researchers are clear about ‘what exists’ to be researched. To focus on a particular discipline – educational psychology – enables a closer focus and potentially facilitates dialogue across associated social science disciplines where a critical realist perspective is well established.

Through a close analysis of a specific psychological construct and a frequently encountered classroom scenario the importance of a critical realist framework for the application of research-based psychology to real-life educational contexts will be demonstrated. This analysis covers the first three of the seven levels of subject matter in the social sciences identified by Bhaskar (Citation2020): the sub-individual level (the ‘unconscious or play of motives’), the individual level and the micro level of small scale social interactions (Bhaskar Citation2020, 116). Similarly, in relation to the elaboration of the transformational model of social activity with the conception of ‘four planar social being’ it places a particular focus on the fourth plane: ‘the unique stratification of our particular embodied personalities’ (Bhaskar Citation2020; Pilgrim Citation2020).

As within sociology there are competing theoretical frameworks with different epistemologies underpinning educational psychology research and practice. It is not the intent here to focus on the wars between neo-positivists and interpretivists, although the argument has been made frequently that a critical realist perspective offers a bridge between these positions (O’Mahoney Citation2011; Elder-Vass Citation2012). It is, rather, to explore how critical realism can be constructively applied to educational psychology – an ‘underlabouring’ which aims to clarify the ontological basis of the constructs typically deployed within it. The psychology of education has pure and applied dimensions both sharing a wide theory and knowledge base ranging from child development, learning and teaching, the dynamics of families and classrooms, special educational needs, mental health, the functioning of groups, schools as organizations, and the influence of culture and community on learning. The task of the applied educational psychologist is to bring into play the research base across these disparate but overlapping fields when enabling others (for example, teachers) better to make sense of a problematic situation which might be inhibiting the learning of a class group or an individual student. It is pragmatically and ethically essential that the psychological constructs which constitute the research evidence base are, in a critical realist sense, regarded as causally effective and real.

These constructs (or entities) are elicited in the process of agency alongside the entities of social structure and culture and drive Archer’s (Citation2000, Citation2003) internal conversation and the generation of Bhaskar’s (Citation1998) reasons. If it can be demonstrated that critical realist criteria for entities to be real can be satisfied by psychological entities there is a basis for an overarching critical realist perspective across both disciplines with the consequence that theory development has a shared ontological foundation. A case has already been made for a critical realist perspective when researching the broad field of education (Scott Citation2005, Citation2010); an examination of psychological theory applied to education complements this and therefore holds the possibility of a greater interdisciplinary dialogue between psychology and sociology contributing to the resolution of the tension between a focus on individual agency and a focus on social structure, which is the goal of the application of critical realist thinking to social science (Sayer Citation2000).

I shall begin with a brief overview of Bhaskar's and Archer's thinking on agency and structure which includes some of the work of others who have further developed Archer's idea of the internal conversation. While this will be familiar territory for many readers of this journal it provides a context for considering how the ‘interiority’ aspects of both models can be extended to embrace psychological constructs outside of the purview of sociology and at a deeper level than the aspects of mind generally referred to in discussions of individual agency. I then examine briefly the intransitivity of psychological attributes of mind and consider a specific example of a psychological entity: self-efficacy. The causal power of teacher self-efficacy is then illustrated through an imagined classroom scenario where, alongside the causal power of other psychological and social and cultural entities it leads to agency. Self-efficacy is then further examined against criteria of ontological depth and emergence.

Individual agency distinct from social structure

One of the concerns of the key proponents of critical realism within philosophy and social theory has been to justify the ontological status of the individual as distinct from social structure and to argue the case against their inseparability (Bhaskar Citation1998; Archer Citation2000, Citation2003). Bhaskar (Citation1998) represented this in his transformational model of social activity (TMSA) about which he writes:

I want to distinguish sharply, then, between the genesis of human actions, lying in the reasons, intentions and plans of people, on the one hand, and the structures governing the reproduction and transformation of social activities, on the other; and hence between the domains of the psychological and the social sciences. (Citation1998, 35)

Society … … provides necessary conditions for intentional human action, and intentional human action is a necessary condition for it. Society is only present in human action, but human action always expresses and utilises some or other social form. Neither can, however, be identified with, reduced to, explained in terms of, or reconstructed from the other. There is an ontological hiatus between society and people, as well as a mode of connection (viz, transformation) that … .. other models typically ignore. (Citation1998, 36–7)

Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003, Citation2007) has refined the TMSA through her morphogenetic/morphostatic approach which places greater emphasis on the mediation processes between social structure and agency alongside an emphasis on the cyclical nature of the model and structural elaboration. The key aspect of her approach, in agreement with Bhaskar, is that of an analytical dualism which regards social structure and individual agency as separate but symbiotically related mediated entities with a history and a future:

[They] are conceptualised as distinct strata of reality because they have different, irreducible and causally efficacious properties and powers. For example structures can be centralised, whilst people cannot, and people can exercise reflexivity, which structures cannot do. (Archer Citation2007, 152)

… … … to advance the ‘internal conversation’ as the process of mediation ‘through’ which agents respond to social forms fallibly and corrigibly, but, above all intentionally and differently – is to attribute three properties to their reflexive deliberations. The internal conversation is held to be (a) genuinely interior, (b) ontologically subjective, and (c) causally efficacious. (Archer Citation2003, 16)

There is therefore a sense that Bhaskar's ‘reasons, intentions and plans’ reached through ‘cognitive activity’ can be viewed as the culmination of an internal conversation which is known only to the individual and not accessible to others (i.e. ontologically subjective) generating the cognitive and conative reason which in turn precipitates action.

A critical realist perspective of psychological entities

If the internal conversation is the causally efficacious, subjective mediation process focusing on causally efficacious and objective social forms and individual identity, what can we say about the entities of mind (which are the preoccupation of psychologists) which, in Archer's sense, drive the nature and outcome of the conversation and in Bhaskar's terms constitute ‘cognitive activity’? Bhaskar (Citation1998) regards social structures as ‘pre-existing’ to agency; similarly, Archer regards existing social and cultural forms as an available element of observation (prior to agency) within the internal conversation and regards identity as the pre-existing ‘Me’ which informs the conversation. If we accept this to be the case, the psychologist is interested to consider what other entities subsuming ‘identity’ can be considered to pre-exist and to be ‘real’ and causally efficacious to human action through influencing the internal conversation or the construction of ‘reasons’.

As a discipline, psychology has developed theory about a wide range of entities which are considered as individual attributes of mind and which influence agency alongside social structure and culture although the necessity of understanding social and cultural context is fundamental when it comes to ways in which these attributes are activated within the individual and how they become incorporated within hypotheses designed to explain particular actions. Alongside aspects of identity, examples of these entities of mind are ‘attitude’, ‘sense of belonging’, ‘formal operational thought’, ‘working memory’, ‘attachment style’, ‘self-efficacy’. Psychological research has developed bodies of theory involving constructs such as these which aim to provide explanations of human behaviour and development. These are all considered to be entities which have a causal role in influencing or determining the behaviour of an individual in a particular context at a particular moment.

Such attributes of mind can be considered to act in combination much as do the variety of structural and cultural forms processed through the internal conversation, generating reasons and precipitating agency at any moment. They are part of the ‘Me’ with which the ‘I’ engages in the moment. Thus, taking an example from education, in addition to general features such as gender and ethnicity, the identity of a student will ‘contain’ a particular attitude towards authority, their sense of competence as a learner, their sense of belonging to a particular institution and self-perceived peer status, all of which will influence their action alongside their observation of what is expected of them as a student, their contractual relation with the institution (the student role), family and societal norms – all of which are mediated by an ongoing internal conversation specific to her actual circumstances at a particular time.

In light of this it is pertinent to ask how, within a critical realist framework, we might apply the criteria for a psychological entity to be ontologically real. Groff (Citation2004) returns to Bhaskar’s (Citation1998) original argument to justify the applicability of what she then termed ‘transcendental realism’ to social science and she, after Bhaskar, poses the question: ‘What would society have to be like, in order for the model of science associated with transcendental [i.e. critical] realism to be applicable to the study of it?’ (Groff Citation2004, 104–5). In response, again following Bhaskar, she identifies three conditions:

That it be intransitive

That it be characterized by ontological depth

That it contains causal mechanisms.

She further states:

The argument is that social structures are intransitive in the sense that they both pre-exist and are presupposed by the actions carried out by persons; they provide for ontological depth in that they are the not-directly-empirically-accessible generative mechanisms that give rise to manifest events; they are causal mechanisms in that they both enable and delimit intentional activity. (Groff Citation2004, 105)

In addition to the three conditions cited above, there is a further expectation that an entity which is ontologically real be ‘emergent’ (Bhaskar Citation1998). By this is meant that it is more than the sum of its parts, has properties that are not possessed by the parts in isolation and that its causal power ‘emerges’ from this fact and cannot be attributed to one or more of its parts by simple combination. Bhaskar (Citation1998) deploys this idea of ontological stratification in his argument against reductionism. In turn, an entity is part of a higher order entity which is more than the sum of its parts. Archer (Citation2003) regards reflexive deliberations as emergent properties because they depend for their existence on ‘components of our mental activities’ (94). It is these components of mental activity which drive reflexive deliberations that I intend to examine more closely within the specific domain of educational psychology. In the case of a teacher, her reflexive deliberations are driven by such factors as, for example, her judgements regarding her instructional and classroom management skills, her identity as a teacher, her sense of belonging to the school, her representative ‘schema’ of a class group and specific individuals within it; these alongside the social relations of employment, membership of a profession with its cultural and ethical imperatives. In the case of a student, the equivalent deliberations are driven by the cognitive skills they brings to the learning environment, their cognitive and emotional development, their sense of belonging to a school or other learning institution, their sense of competence, their perceived social standing in the peer group; these alongside the culture of their family and community and its relations with education.

In response to these four conditions identified by Bhaskar each is addressed in the following sections. First, Bhaskar's arguments which support the intransitivity of reasons are applied to some psychological constructs frequently employed within educational psychology. Intransitivity is further considered through consideration of one particular psychological entity, ‘self-efficacy’ which then leads into the remaining criteria of ontological depth, causal power, and emergence. Self-efficacy is examined as an illustration of ‘fit’ with Bhaskar's TMSA and Archer's and subsequent others’ (e.g. Mutch Citation2004) proposals for the internal conversation.

The intransitivity of psychological attributes of mind

Bhaskar distinguishes two categories of objects within science: transitive and intransitive. The intransitive objects of science are defined as ‘the real things and structures, mechanisms and processes, events and possibilities in the world … . [not] in any way dependent on our knowledge, let alone perception, of them’ (Bhaskar Citation1998). The transitive objects of science are the cognitive outcomes of scientific practice, in particular theories; these are in constant development and therefore subject to change. In relation to natural sciences Bhaskar viewed intransitive objects as those which would exist whether humans were present or not to investigate them. In his later application of transcendental realism to the social sciences via critical naturalism and the transformational model of social activity, Bhaskar widened this definition by asserting that intransitivity is said to apply to social structures (which are dependent on human existence) in the sense that they both pre-exist and are presupposed by the actions carried out by persons (Bhaskar Citation1998; Groff Citation2004; Richards Citation2018).

In what sense can intransitivity apply to entities of the mind which are the everyday concern of psychology? In parallel with the question posed for social scientists which asks what structures and processes in society must be in place for a certain conscious human activity to take place, psychologists can ask what structures and processes must similarly be in place in the mind for that conscious (and maybe unconscious) intent behind human activity to exist. In arguing for reasons to be the pre-eminent causal factor behind an individual's specific behaviour at a particular time Bhaskar (Citation1998) essentially proposes them to be intransitive objects. They are real and ontologically subjective entities with causal power which exist in the same way that, in societal terms, the wage relation exists. They take a specific form, alongside social structures, to influence specific behaviour at a specific moment in a specific context. They exist prior to the behaviour and shape it. Note that this specific form does not imply a complete consciousness of the antecedents of reasons, i.e. that the individual in principle could provide a full account of them. Bhaskar (Citation1998, note 32, 116) argues that to draw a distinction between consciousness (in Archer's terms consciousness objectively exists but is necessarily subjective) and the ‘adequate description’ of consciousness is necessary for there to be a science of consciousness. In other words, reason and consciousness are ontologically real and distinct from the epistemological status of individual knowledge or understanding of them. Thus, the individual's professed (dishonest, delusional or otherwise) awareness of a reason behind an intention to act is epistemological and transitive, and not an ontological issue. To confuse the two, or to regard our knowledge of reason with the existence of reason is to commit the epistemic fallacy. Critical naturalism proposes that there separately exist ontologically real, to be discovered, reasons (which may or may not parallel those in awareness and given verbal expression) for intentional behaviour. It is important to maintain a similar distinction in relation to psychological constructs which are the generational mechanisms for reasons and for the internal conversation.

To ascribe intransitivity to psychological constructs in parallel with constructs describing social structures (entities ‘external’ to the individual) psychological constructs (internal to the individual) such as ‘identity’, ‘attitude’, ‘impulsivity’, ‘sense of belonging’ can be said to ‘pre-exist’ in the sense that they exist as entities separately in the mind from the immediate conscious intention behind individual agency in context C at time t. As Richards (Citation2018) says in relation to the intransitivity of social structures, they ‘retain their identity at an ontological level while at a transitive level they may be approached and described in various ways’. An individual will have a sense of belonging (say to a particular institution or culture) and this psychological entity will have existed prior to an event and will continue to exist after it either similarly or changed in some way. There is an exact parallel here with Archer's theory of morphostasis and morphogenesis where an overarching identity is regarded as the key attribute of the individual driving the internal conversation whose subsequent agency may or may not lead to structural change. Thus, ‘identity’ is, for the psychologist, a ‘structure of mind to be investigated’ independently of (transitive) theories of identity which are the product of the investigation or the self-described, conscious awareness of identity of an individual in context C at time t. The investigative research process, of course, is most likely to engage with the specific, self-aware identities of the individuals participating in the investigation – perhaps revealed through a specific research instrument such as a questionnaire. There is consequently in psychological research (and indeed applied psychological practice) a continuing movement between transitive and intransitive dimensions and a necessary requirement continually to be alert to this transition. This is further explored through the psychological entity of self-efficacy which is defined in the following section.

A specific example: self-efficacy

With the aim of examining intransitivity in more depth I intend to consider it in relation to the psychological construct of self-efficacy. As will become apparent, this has the advantage of a direct (lower level) connection to the broad construct of identity and hence a point of contact with sociological discussion of the individual. This will also be a means of considering the criteria of ontological depth and causal power. Self-efficacy is a focus for educational psychology research (e.g. Holzberger, Philipp, and Kunter Citation2013) and practice and more generally to research into skills-based practice across a wide range of disciplines including health, medical training, business and international affairs (Artino Citation2012) and leadership development (Hannah et al. Citation2008). As an underpinning construct in psychological theories which aim to better understand the factors which facilitate and hinder skills development and the specific application of skills there is a clear benefit to education. Teacher training and continuing professional development aim to foster self-efficacy, not just in the core task of instruction but also in the skills of classroom management and teacher-student interaction. In turn, teachers aim to foster self-efficacy in their students across a wide range of skills, obvious examples being reading and numeracy, communication and social interaction. Recent years have seen significant investment in developing the leadership skills of headteachers and senior staff in schools and colleges, a central objective being to enhance the leadership self-efficacy of staff. The relevance of self-efficacy to the psychology of education is clear, and the applied educational psychologist is required to have an in-depth understanding of self-efficacy theory to apply in her consultative practice, not to mention in relation to her own skills.

Following the definition of self-efficacy I present a model illustrating its application to a specific educational context: a moment of critical teacher-pupil interaction where it is activated alongside other proposed causal mechanisms likely to be activated in such a real-life event. This is highly relevant to research in education since teacher-pupil interaction is the essential systemic ingredient for learning to take place; it is similarly a core issue for applied educational psychology practice when the focus is on an individual or group of pupils who are the subject of inquiry or concern. The theoretical construct of self-efficacy was developed by Bandura (Citation1982). He defines it as follows:

Perceived self-efficacy is defined as people's beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives. Self-efficacy beliefs determine how people feel, think, motivate themselves and behave. (Bandura Citation1994)

Mastery experiences, most particularly those where achievement is reached through persistent effort,

The availability of competent models who transmit knowledge and teach observers effective skills and strategies for managing environmental demands,

Access to others who encourage and raise expectations; in addition to raising people's beliefs in their capabilities; they structure situations for them in ways that bring success and avoid placing people in situations prematurely where they are likely to fail often,

A positive mood which combats depressive tendencies to view physical difficulty or slow progress as symptoms of failure (Bandura Citation1994).

As an example, unrelated to education, consider a person's sense of self-efficacy in playing tennis. Self-efficacy will be enhanced if the person has experiences of winning games against opponents who they initially regarded as players on a par or better than themselves, and particularly if this was the result of persistence and concentration. Having a tennis coach similarly enhances self-efficacy through demonstration and structured practice and gradually increasing demands through competition selection. On any occasion a crowd of supporters can do wonders for perceived self-efficacy through straightforward encouragement which raises positive mood and combats any sense of impending failure.

Self-efficacy is therefore regarded as a structure of mind which critically influences human action. Most often it is deployed in psychological theory in relation to specific skills or competences but can also be regarded as a broader construct relating to the individual's overarching sense of self and therefore a significant element in an individual's sense of personal identity. Perceived self-efficacy will not determine a specific behaviour but will generally set limits on it. Its development is rooted in a history of interaction with the different social and cultural mechanisms which provide the four contributors identified above, alongside individual attributes such as motivation and competence (or lack of it) in specific skills. If the individual senses themselves as insufficiently competent in relation to some task demand, i.e. has low self-efficacy to undertake a response which will meet the requirement of the task (not necessarily implying a specific behaviour) in a particular context this will lessen the likelihood of a constructive response being made. Likelihood is the limit of what can be said because of other cognitive and affective entities of the mind and aspects of the social structure and cultural context within which the potential action could take place. Anxiety, for example, or wider self-image might over-ride any decision based upon self-efficacy alone, as might perceived social or cultural norms or authority relations. In combination, these social, cultural and other psychological factors can be considered to constitute a generative mechanism for Bhaskar's reasons and Archer's internal conversation. Furthermore, they can be considered to have causal power in relation to a specific reason and, through this, determine a specific piece of behaviour. Psychology's interest in self-efficacy over and above its power as an explanatory construct is therefore related to a variety of questions such as the relative contributions made by the four contributing factors identified above, and more broadly the conditions for optimizing skills development, the development of organizational leadership, the investigation of individual differences and the exploration of the relationship between self-efficacy and emotional states such as depression.

Although regarded as an individual attribute the development of self-efficacy is clearly a product of the individual's engagement with the physical and social world. Although Bandura is typically associated with cognitive aspects of mind, self-efficacy is evidently also associated with affective states. Those involved in education and in the training of professionals will be well aware of the wide range of emotions which accompany the development of the internal sense of self-efficacy. This aspect touches upon social realist accounts of the development of emotion and identity, in particular from Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003).

The role of teacher self-efficacy in a specific teacher-student interaction

I now intend to apply the considerations so far to an imagined, but realistic, example of a typical interaction between a teacher and a student in a school classroom prompted by behaviour which the teacher perceives as undermining the learning of the student and for others in the class. This represents something which, if recurring, might warrant the involvement of an educational psychologist. The interaction itself is an example of an important area of educational psychology research: classroom behaviour management (see, for example, Merrett and Wheldall Citation1993; Hettinger et al. Citation2021). This interaction may be a situation requiring a response by the teacher to an unpredicted event and where the time available to develop a reason for action or to have an internal conversation may be extremely limited; on the other hand, it may derive from a series of cycles of observation and agency which have generated an extended internal conversation where a variety of options for intervention can be considered.

Consider the following vignette. A primary school class teacher is in her second year of teaching and currently in charge of a Year 5 class of 9–10 year olds. She has been happy with her first appointment since the staff have been generally supportive and the school has a ‘good’ OfSTED rating. Within the class group there is a strong commitment to learning fostered by a school culture which emphasizes success at all levels of achievement. Within the class group there are a number of students whose backgrounds are known to be troubled and who can show poor emotional self-regulation and concentration. One student in this group has on this day been persistently inattentive and talkative, distracting those around him.

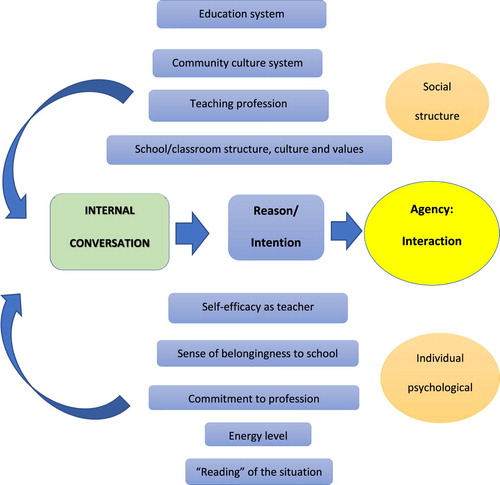

At this moment, the teacher has to decide at what point to stop ignoring this behaviour and to intervene with the student. This can be represented in below which illustrates the moments prior to and when the teacher acts.

Figure 1. Some of the societal and individual entities impacting on a specific case of teacher agency.

There will be a combination of social/cultural structures and individual psychological entities impinging on the teacher's experience at this moment, not all of which will she be aware of or consciously bringing to mind. These will be being processed directly and indirectly through an internal conversation. By way of illustration, and referring to , there are social structures that pre-exist and (if remotely) impact on specific behaviour options. Her response in this interaction will be influenced at a distal level by her empirical (‘and likely below the surface’ of consciousness) awareness of such things as her developing role as a teacher with a sense of her own authority and more proximally by her acceptance of the dominant school values and culture which results in a particular sense of belonging and which provides the wider social context for the interaction. There will also be an immediate set of relationship structures within the class group which impact on her internal conversation prior to agency. She will also have a ‘schema’ generating her understanding of this pupil which enables her to formulate predictions about the likely consequences of her intervention. She will also have at this moment a physiological state which determines her energy level and mood. Alongside all of these she will have a particular sense of her self-efficacy not just as a teacher and ‘classroom manager’ but more specifically in relation to this pupil. In this model, the causal power of these social, cultural, physiological and psychological entities in respect of agency testifies to their intransitivity and status of being ontologically real. Her awareness of them in contributing to her reasons for acting is an issue for the empirical domain. The empirical domain of awareness provides only limited and mediated versions of the real (Sayer Citation2000).

If we consider the social structures and cultural factors it is unlikely that she will be consciously engaging with the nature of the teaching profession at this moment, although it will be influencing in the background her decision; similarly, with her sense of belongingness to the school as an institution. Most significantly she will be using her experience of this pupil and the class group to build her empirical ‘reading’ of the situation and hypotheses regarding the consequences of different responses from her towards the pupil. Crucial to this will be her sense of self-efficacy both as a teacher and relative to this class group and this pupil. This is the specific internal conversation which mediates between these social, cultural and subjective psychological entities and leads to a reason and intention to act. The consequences of her agency will feed back and influence all of the psychological entities caught up in the prior internal conversation and lead to a further, subsequent conversation. Sense of self-efficacy might be enhanced if the intervention is deemed successful and energy level might increase. Following Archer's (Citation2003) morphostasis/morphogenesis model the social and cultural entities may also be modified.

This example is of an interaction. The other parties to this are firstly the pupil and secondly the class group, both as individuals and also as a group entity. For the pupil, at this same moment in time, there will be a group of social structures which entail relations (for example as a child of his family, as a pupil, as a peer group member) and psychological structures such as his own sense of self-efficacy, attitude to authority, self-concept as a learner, sense of belonging to school, anxiety, emotional well-being. In judging the challenging interaction to be successful (by the teacher) both will have experienced small shifts in the constellations of their respective psychological entities which were activated by the context for the subsequent agency. For the other pupils in the class group there will be their own internal conversation which leads to agency or revised notions of agency as a result of their observations of the event. Aspects of class group identity will have undergone a small change as will the culture of the class, for example, its beliefs about authority relations, confidence or otherwise in the teacher, what it means to be a learner.

Causal power

Self-efficacy can be considered as an aspect of identity and alongside Archer (Citation2003) other critical realist writers have written about identity, assuming it to be intransitive and real (e.g. Marks and O’Mahoney Citation2014). In the above scenario, there is a presumed causal power attributed to self-efficacy which can be further justified against criteria for ontological depth and emergence (see below). The teacher's intentional agency follows a rapid internal conversation which culminates in a decision underpinned by a reason (which, according to Bhaskar (Citation1998, 80) possesses the causal power for the response, thereby characterizing it as intentional) and is an emergent entity comprising a number of subordinate entities identified in of which self-efficacy is one, each with their own causal power variously exercised, to generate the causal power of the reason. From the perspective of the internal conversation, this can be considered to be the ‘productive cause’ (Groff Citation2017) and the teacher's empirical experience of this combination of entities can be regarded as the total subjective context for the response.

A further observation can be made about the nature of the causal powers held by emergent social and cultural entities (for example, ‘school culture’) and emergent psychological entities. Lewis (Citation2000) has argued that there are two types of causation at work in the relation between agency and structure. He builds on the Aristotelian distinction between material and efficient causes. An entity which generates something (in this case, purportedly, human action) is regarded as an efficient cause in the same way that a sculptor is an efficient cause in the production of a piece of art. The causal power resides within the sculptor and is intrinsic to the sculptor as a person. Material causality refers to the constraints that the material being used has on the final outcome; thus, to sculpt in wood presents a different set of opportunities and constraints compared to sculpting in plaster and therefore has a causal impact on the outcome. Lewis (Citation2000) has argued that social structures possess causal power in relation to material causality rather than efficient causality and on this basis can be regarded as real. This extends the points made by Bhaskar (Citation1998) in his discussion of Durkheim and Weber as a preface to his presentation of a transformational model of social activity (34–5): ‘society is both the ever-present condition (material cause) and the continually reproduced outcome of human agency’ (Bhaskar's italics). In contrast, psychological entities can be regarded as efficient causes within the TMSA and behind the internal conversation since they reside within the individual and lead directly to agency according to the extent to which they are activated, whereas the social and cultural entities of can be regarded as material causes. As with a piece of sculpture there lies a combination of efficient and material causation behind agency.

The significance of ontological depth

Returning to the criteria for the applicability of a critical realist approach to an object of study, in this case, the event of the interaction between a teacher and a student, Bhaskar (Citation1998) distinguishes between experiences, events and mechanisms. These correspond to domains respectively identified as ‘the empirical’, ‘the actual’ and ‘the real’. The empirical domain is that of experience, the actual domain is that of events happening which may or may not be experienced, and the real is the domain of (unseen) causal mechanisms that lie behind events and experiences. These distinctions define what is referred to as ontological depth.

The discussion above has engaged all three domains. I have proposed that self-efficacy is ontologically real and has causal power. Groff (Citation2004) justifies placing social structures in this domain because ‘they are the not-directly-empirically-accessible generative mechanisms that give rise to manifest events’ (105). We can similarly argue that self-efficacy is an equivalent mechanism, one amongst many, giving rise to manifest events – the actual domain – which in the above example is the particular, observable, intervention produced by the teacher, the pupil's response and any response to it within the class group. These mechanisms retain their ontologically real status alongside her empirical, specific, in this moment of time, understanding and experience and represent the ‘Me’ which the ‘I’ is about to interrogate in the internal conversation (Archer Citation2003, 112ff.)

As already noted, there is an obvious difference between social structures and psychological structures when we consider the causal factors that ‘pre-exist’ within the mind of the teacher – externality does not apply. Following Bhaskar we are reliant on the distinction between an entity of mind and the manifestation of that entity in the mind of the individual (not necessarily entirely in consciousness). Let us suppose that she judges this challenging interaction to meet some criterion of success, for example, the actual event of the pupil calming down and refocusing on the task in hand; the empirical event which is her experience of this success is likely to impact on her sense of self-efficacy and will most likely be immediate and possibly significant. Maintaining Bhaskar's distinction between reason and the consciousness of reason we can draw a similar distinction between self-efficacy and the consciousness of self-efficacy at this moment. It is the empirical consciousness of self-efficacy that will be immediately impacted by the successful interaction – it will be heightened (or otherwise) and be describable as such and felt to be epistemologically ‘true’ at that moment. In the same way that her earlier sense of self-efficacy influenced her behaviour in this interaction we can hypothesize that her approach to a future challenge will be modified accordingly on the basis of her revised sense of self-efficacy.

A researcher might choose to investigate this hypothesis and explore the links to future challenging interactions and thereby provide further evidence for the causal power of self-efficacy and justify its existence as an intransitive entity. A further question for research might be its relative power within the complex of other causal mechanisms which lead to the teacher's agency. There is therefore a constant interplay between the transitive and intransitive dimensions in the research process.

Emergence

Returning to the CR perspective on whether to regard an entity as real, there is a requirement that it be ‘emergent’ (Bhaskar Citation1998). By this is meant that it is more than the sum of its parts, has properties that are not possessed by the parts in isolation and that its causal power ‘emerges’ from this fact and cannot be attributed to one or more of its parts by simple combination. In turn, an entity is part of a higher order entity which is more than the sum of its parts, of which, in this instance, self-efficacy is one.

In a detailed account of emergence from a critical realist perspective Elder-Vass (Citation2005) echoes Bhaskar in arguing that both the whole and its parts be regarded as entities and that the parts subsumed by the whole are ‘significantly structured’ in relation to the whole. An entity is defined as ‘a persistent whole formed from a set of parts, the whole being significantly structured by the relations between these parts’. The new properties of the whole are termed emergent properties and are contrasted with ‘resultant properties’ which are not new and are possessed by the parts in isolation or aggregation (Elder-Vass Citation2005, 318–19).

Returning to the entity of self-efficacy and Bandura's definition that it is a constellation of beliefs that ‘determine how people feel, think, motivate themselves and behave’ (Bandura Citation1994), and considering the first aspect of emergence: what ‘lower order’ entities can be considered to make up self-efficacy? Referring to the four contributors to self-efficacy cited earlier we can consider the subjective consequences of each of these four components in relation to a specific skill. ‘Mastery experiences’ will reinforce context-specific skill and knowledge. ‘availability of competent models’ will lead to enhanced awareness and possibly elements of skill. ‘Encouragement and raised expectations’ provides a provisional sense of self-belief. A ‘positive mood’ generates energy and resilience. These different subjective consequences (the parts of the whole) can therefore be summarized as memory of specific episodes of skill mastery; specific knowledge; provisional self-belief; perceived energy level and commitment to persevere. Together they can be considered to generate, through their structural integration, the belief that new and potentially different challenges within the skill area concerned can be met which go beyond any previous experience and which determines the outcome expressed in Bandura's definition of self-efficacy in relation to a specific skill challenge. It is, of course, possible that one or two of these elements activated outside of the integrated four might generate a false or illusory sense of self-efficacy which leads to agency; for example, a combination of knowledge from observation of another combined with a commitment to persevere leads to agency which fails, in which case the outcome will reveal the extent of the illusion and illustrate the fact that self-efficacy, as a causal mechanism, is a development from repeated experience which contains all four elements.

What can we say about the structural relationships between these parts and the whole? It is perhaps best expressed through an interacting subjective network in which all four cognitive and conative components feed into self-efficacy through a structured engagement with each other. This structural engagement is organized through the individual's perception of the social and cultural context which determines that this particular skill is required at this moment in time and is likely to be a key element of the internal conversation at that time.

In the case of the teacher deciding upon an action in relation to her inattentive pupil she will be able to cite specific episodic memories (in this case of teaching or, more specifically, of challenging interactions with pupils), memories of observing relevant models of teacher-pupil interaction (perhaps during initial training), encouragement that comes (in this case) from the culture of the school alongside whatever mood state she may find herself in on that occasion. No single one of these components in itself is likely to provide the sense of being able to manage this pupil at this moment, however in combination and structured by the immediate context they potentially will. This emergent property of teacher self-efficacy becomes a significant subjective entity within the complex of entities in which leads to agency.

The perceived consequences of the action taken (a verbal utterance, an emotional tone, a facial expression, a physical posture) will act as feedback which leads to morphogenesis and a revised perception of self-efficacy. This will have taken place over the time taken for the initial observations, the inner conversation, the intervention, the consequent behaviour of all present (this in the domain of the actual) and illustrates a different perspective of emergence: the diachronic aspect as distinct from the synchronic (Elder-Vass Citation2005). The emphasis so far has been on the synchronic aspect which refers to the structural relations between parts which lead to the emergent property of teacher self-efficacy and are stable and intransitive. The diachronic aspect refers to the development of a phenomenon over time and in the case of the teacher the consequential change brought about by feedback illustrates a transitive and developmental aspect whereby the perception of self-efficacy changes with repeated experience.

In the synchronic sense an emergent entity has properties greater than those possessed by its parts and can in turn be a structural component of a higher order entity which has properties not possessed by it. Of what can self-efficacy be considered a constituent part? As noted earlier, self-efficacy can be considered part of personal identity. Personal identity has properties and causal power which impact on behaviour in ways additional to that of self-efficacy alone and are unique to itself. Identity is a complex of many elements which include self-esteem, self-image, gender, ethnicity and engages intimately with social identity (Marks and O’Mahoney Citation2014). Self-efficacy can therefore be considered to be synchronically emergent in terms of being a part of a greater whole whose properties are greater than those of self-efficacy alone.

Conclusions

This paper has aimed to establish the value of an explicit critical realist perspective to educational psychology research and practice through the application to the psychological construct of self-efficacy of Bhaskar's criteria for an entity to be ontologically real. In so doing it has presented a psychological analysis of individual agency alongside and complementary to the sociological analysis prevalent in critical realist writing. Bhaskar's realist ontology has been addressed at length in the preceding sections. Embedded within it is the fundamental premise that what is real carries causal power which determines events or, in the case of the social sciences (including psychology) determines the likelihood of events and sets limits on them.

Through a detailed examination of an important psychological construct – self-efficacy – and its applicability to a real-world educational scenario it has been argued that criteria for an entity to be ontologically real have been met. Self-efficacy, alongside other psychological, social and cultural entities has been presented as a causal mechanism for the generation of Archer's internal conversation which can be considered to underpin Bhaskar's reasons which in turn lead to agency in the context of a typical example of critical teacher-pupil interaction. Self-efficacy (more specifically teacher self-efficacy) further meets criteria for intransitivity through its pre-existence in the mind and its pre-supposition by the agency of the teacher. It provides for ontological depth by existing in the domain of the real and the empirical as well as being a synchronically emergent psychological entity with powers that are distinct from those of its component parts. In principle, similar arguments can be made in respect of other psychological constructs. As Bhaskar notes (Citation2014) there is a dearth of texts which examine applied critical realism, or ‘critical realism in action’. Educational psychology provides a highly appropriate context for this and its successful application to real-world educational settings requires a bringing together of psychological and social science theory. If the transitive objects of psychological and social science are seen to have an equivalent ontology which sets similar criteria for what can be considered real and possess causal power there is a stronger basis for interdisciplinary engagement and theory development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roger Booker

Roger Booker is Associate Professor in the Educational Psychology Group at University College London and has been responsible for developing the epistemology curriculum for the Group's two doctoral programmes. A current priority is to establish a greater understanding within the educational psychology profession of the ontological and epistemological basis of applied educational psychology practice. He has also developed leadership programme for Principal and Senior educational psychologists designed to increase leadership self-efficacy in community services.

References

- Archer, M. 2000. Being Human, the Problem of Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. 2003. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Artino, A. R. 2012. “Academic Self-Efficacy: From Education Theory to Instructional Practice.” Perspectives on Medical Education 1 (2): 76–85.

- Archer, M. 2007. “The Ontological Status of Subjectivity.” In Contributions to Social Ontology, edited by C. Lawson, J. Latsis, and N. Martins, 151–164. London: Routledge.

- Bandura, A. 1982. “Self-efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist 37 (2): 122–147.

- Bandura, A. 1994. “Self-efficacy.” In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. 4, edited by V. S. Ramachaudran, 71–81. New York: Academic Press.

- Bhaskar, R. 1998. The Possibility of Naturalism. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. 2014. Foreword to Edwards, K., Mahoney, J. and Vincent, S. Studying Organisations Using Critical Realism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bhaskar, R. 2020. “Critical Realism and the Ontology of Persons.” Journal of Critical Realism 19 (2): 113–120.

- Elder-Vass, D. 2005. “Emergence and the Realist Account of Cause.” Journal of Critical Realism 4 (2): 315–338.

- Elder-Vass, D. 2007. “For Emergence: Refining Archer’s Account of Social Structure.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 37 (1): 25–44.

- Elder-Vass, D. 2012. “Towards a Realist Social Constructionism.” Sociologia, Problemas e Praticas 70: 9–24.

- Groff, R. 2004. Critical Realism, Post-Positivism and the Possibility of Knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Groff, R. 2017. “Causal Mechanisms and the Philosophy of Causation.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 47 (3): 286–305.

- Hannah, S. T., B. Avolio, F. Luthans, and P. D. Harms. 2008. “Leadership Efficacy: Review and Future Directions.” Management Department Faculty Publications. Paper 5. University of Nebraska.

- Hettinger, K., R. Lazarides, C. Rubach, and U. Schiefele. 2021. “Teacher Classroom Management Self-Efficacy: Longitudinal Relations to Perceived Teaching Behaviour and Student Enjoyment.” Teaching and Teacher Education 103), (in press)_.

- Holzberger, D., A. Philipp, and M. Kunter. 2013. “How Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Is Related to Instructional Quality: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Educational Psychology 105 (3): 774–786.

- Lewis, P. 2000. “Realism, Causality and the Problem of Social Structure.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30 (3): 249–268.

- Marks, A., and J. O’Mahoney. 2014. “Researching Identity.” In Studying Organisations Using Critical Realism, edited by K. Edwards, J. Mahoney, and S. Vincent, 66–85. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maxwell, J. A. 2012. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Merrett, F., and K. Wheldall. 1993. “How Do Teachers Learn to Manage Classroom Behaviour?” Educational Studies 19 (1): 91–106.

- Mutch, A. 2004. “Constraints on the Internal Conversation: Margaret Archer and the Structural Shaping of Thought.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 34 (4): 429–445.

- O’Mahoney, J. 2011. “Critical Realism and the Self.” Journal of Critical Realism 10 (1): 122–129.

- Pilgrim, D. 2017. “Critical Realism, Psychology and the Legacies of Psychanalysis.” Journal of Critical Realism 16 (5): 468–482.

- Pilgrim, D. 2020. Critical Realism for Psychologists. London: Routledge.

- Richards, H. 2018. “On the Intransitive Objects of the Social (or Human) Sciences.” Journal of Critical Realism 17 (1): 1–16.

- Sayer, A. 2000. Realism and Social Science. London: Sage.

- Scott, D. 2005. “Critical Realism and Empirical Research Methods in Education.” Journal of the Philosophy of Education 39 (4): 633–646.

- Scott, D. 2010. Education, Epistemology and Critical Realism. London: Routledge.