This themed issue of Journal of Critical Realism has a focus on interdisciplinarity, health and well-being.Footnote1 Specifically, the articles address topics such as homelessness (Hastings), obesity (Kanagasingam et al.), alcoholism (Edwards and Burton), urban planning (Næss), issues of democracy and accountability in contexts of work safety (Weihe and Smith-Solbakken), the effect of neoliberalism on health (Alderson), and debates about mental health (Pilgrim). However, despite their varied content, each article shares a common engagement with interdisciplinarity. Critical realists will not be surprised that interdisciplinarity features in all the articles submitted to this issue, because, in the words of Bhaskar:

Nowhere is the need for genuine interdisciplinarity more evident than in research related to health and wellbeing. For a human being is patently a totality and cannot be studied as a congeries of distinct and separable parts. Thus, a person cannot be perceived as being made up of a number of parts that relate to distinct disciplines. (S)he is a totality; and therefore requires treatment in a thoroughly interdisciplinary way. (Bhaskar in Bhaskar, Danermark, and Price Citation2017, 3)

Here is what some of the authors say about the need for interdisciplinarity:

Once I accepted the logic of stratification of the social world, to explain homelessness I was required to engage with structures and mechanisms at any relevant level of the social world implicated in causing its outcome. (Hastings Citation2021).

For obesity research, the notion of a ‘diffusive biosocial responsibility that transcends the individual and the present time’ (359) underscores the need to move our lens beyond lifestyle or genetic interventions, towards a biosocial model that incorporates biology and social positionality. (Kanagasingam et al. Citation2021).

Urban sustainability thus requires profound changes. On the ontological plane, planning theory must move away from anti-realist constructivism and hermeneuticism, towards realism. On the empirical plane, it is necessary to move away from disciplinary tunnel vision towards a critical realist version of interdisciplinarity … (Næss Citation2021)

Yet the silent majority still tends to comply and conform with neoliberal systems. The systems rely on thousands of workers to enforce the harsh health-related policies of universal credit, of deporting asylum seekers, or managing the largest prison population in Europe, or making people homeless. Critical realism’s four planes of social being and interdisciplinary concerns can analyse these powerful influences on health that might not at first seem relevant… (Alderson Citation2021)

However, the critical realist approach to interdisciplinarity is profoundly different from the mainstream approach (Price Citation2014). In this Editorial, I explain how it is different. My hope is that this will make it easier for readers to understand the significance of the articles in this issue, which represent an important break from mainstream versions of interdisciplinarity.

Mainstream versions of interdisciplinarity do not tell us what ‘interdisciplinarity’ is about

Whilst it is commonplace to acknowledge that linking the different disciplines together in an unrelated way, known as multidisciplinarity, is an inadequate approach to achieving the goal of greater wellbeing – and that we should instead aim for some kind of synthesis of the disciplines, namely interdisciplinarity or transdisciplinarity – nevertheless, there is little mainstream clarity about how to achieve such a synthesis (Lindvig and Hillersdal Citation2019). Much of the currently available advice tends towards wishful thinking because it is not based on an understanding of what interdisciplinarity is about. Such advice is reminiscent of the recipes that ancient people used when they described how to make alcohol – before they understood the process of fermentation. These recipes consist of a list of things that one ought to do, following which, and somewhat miraculously, the desired outcome will hopefully be achieved (for example, Katz, Maytag, and Civil Citation1991, 29).

In terms of interdisciplinarity, take for instance this advice from Kelly et al. (Citation2019, 149). They state that to achieve interdisciplinarity, one should:

Develop an area of expertise; learn new languages; be open-minded; be patient; embrace complexity; collaborate widely; push your boundaries; consider if you will engage in interdisciplinary research; foster interdisciplinary culture; and champion interdisciplinary researchers.

… engineers now realise that you get a better technical solution if you (include inputs from the community, including those from various pressure groups). This … implies that more involvement on the part of society means not a better social solution, or a better adapted solution, or one that brings social tranquillity to a community, but a better technical solution. Could not the same conclusion be applied right across the scientific spectrum: that better scientific solutions emerge if there is dialogue with society than if there is not?

One doesn't have a single good criterion as in scientific quality control, where you can always fall back on criteria used in scientific disciplines that allow one to say something is “good physics,” “good field biology,” or “good botany.” You don't have this anymore. (Gibbons and Nowotny Citation2001, 71)

Instead, they urge communities to check the quality of the science by asking researchers ‘what have you lately done for us?’ and suggesting, in a typically pragmatist way, that ‘The potential of transdisciplinarity lies precisely here: to obtain a better outcome, to produce better science. We will see how we can get there (Gibbons and Nowotny Citation2001, 71).’ The latter sentence is an honest admission that they did not know, at the time of writing, how to achieve interdisciplinarity. This theme – the need to measure quality through the attainment of valued outcomes via a process of democracy – reoccurs throughout the mainstream contemporary literature on how to deal with complexity, or ‘wicked’ problems, using interdisciplinarity or transdisciplinary (see for example Rittel and Webber Citation1973; Stehr and Weingart Citation2000; Klein Citation2001; Nowotny Citation2017).

There are different versions of a ‘layered reality’

These authors are unable to provide clear advice because they have not fully answered the question of what reality must be like for interdisciplinarity to be possible. I say they have not ‘fully’ answered it, because they have partially answered it. They understand that reality is layered and that the first layer of reality is made of things that we can measure. They correctly critique science that does not swerve from this layer, seeing it as reductionist. Gibbons and Nowotny (Citation2001) call this ‘level mode-1 knowledge’ and Max-Neef (Citation2005) calls it the ‘empirical level’. For Max-Neef, this is the only level that has an ontology, even though he also says that reality is layered, and there is therefore a contradiction in his position. If he were to be faithful to the idea that reality is layered, his other layers of reality would also have ontologies – they would also exist. Therefore, Max-Neef states in relation to this first layer:

This level asks and answers the question ‘what exists?’ Through physics we can learn about quanta, through astronomy we can learn about the magnitude of the universe and the birth of stars. Through biology we can learn about the composition of organisms that defy entropy as open systems. (Max-Neef Citation2005, 7)

In moving beyond this first level of reality, commentators such as Max-Neef, Gibbons and Nowotny argue for a second layer, what critical realists would call the actualist layer of inter-relationships and ‘complexity’. However, they do not address this layer in terms of ontology but in terms of epistemology. Gibbons and Nowotny, therefore, address this actualist level of reality with what they call ‘mode-2 knowledge’, which they see as subjective knowledge created by communities. They, therefore, see it as a ‘social phenomenon’ that can be guided by ‘metaphors taken from mathematical complexity theory’ (Nowotny Citation2005, 29). Max-Neef (Citation2005) also addresses this level in terms of subjective knowledge but sees it as further divisible into three subjective sub-groups, namely, values, norms, and purposes. Max-Neef criticizes Nowotny and others with their focus on community knowledge, but nevertheless, both their versions are deeply rooted in a concept of subjectivity. He states:

An integrating synthesis is not achieved through the accumulation of different brains. It must occur inside each of the brains. (Max-Neef Citation2005, 7)

For Gibbons and Nowotny (Citation2001), access to this subjective layer, which provides disciplinary integration, is through communities and democratic processes; for Max-Neef (Citation2005, 13), access to this integrating subjective layer is through ‘means that induce altered states of consciousness’, such as one might experience in meditation or shamanic rituals; and for Nicolescu (Citation2002, 192), inspired by the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, ‘the different levels of Reality of the Object are accessible to our knowledge thanks to the different levels of Reality of the Subject, which are potentially present in our being’. Nicolescu (Citation2002, 197) also suggests that what connects human subjects and objects is ‘the Great Other, the Hidden Third’, which is also ‘a cosmic breath that includes us and the universe’.

For Bhaskar, the integratedness already exists at the intransitive level of real structures and mechanisms, and it would exist even if there were no people to provide an ‘integrating synthesis’ to theorize its presence. His version of interdisciplinarity does not depend for its existence on community theorizing, altered states of consciousness or cosmic breath. I am not going to comment on the latter two suggestions, but in terms of ‘community theorising’, I argue below that there is, however, good reason for why communities tend to have an excellent track record when it comes to doing the kind of thinking that correctly theorizes the existence of the structures and mechanisms that explain the complexity. However, the fact that communities are good at this kind of theorizing does not tell us what ‘this kind of theorising’ is, neither does it give communities the monopoly on it.

Multimechanisimicity

Bhaskar (pers. com) felt that this assumption, that interdisciplinarity is a subjective entity alone, was embedded even in the term ‘interdisciplinary’, which, with its reference to disciplines, talks only about epistemology. He, therefore, came up with the phrase ‘multimechanismicity’ as a way to name the integrated entities present at the level of the real, which we discern through interdisciplinarity. He defined multimechanismicity as the idea that:

… outside a few experimentally (and even fewer naturally occurring) closed contexts a multiplicity of causes, mechanisms and potentially theories is always involved in the explanation of any event or concrete phenomenon. This is an index of the complexity of the subject matter of any science. (Bhaskar Citation2016, 86)

Without structures and mechanisms, complexity can seem overwhelming

Authors such as Gibbons, Nowotny and Max-Neef assume that the first and second layersFootnote2 exhaust reality, but this leaves them with a pessimistic, overwhelming position because they are then faced with a reality which is so complex that it is impossible to fully describe; and it seems governed by unpredictability and randomness. It is the existence of this complexity that, for these authors, ‘necessitates an interdisciplinary approach’ (Klein Citation2001, 43). One way to attempt to cope with this complexity is with the use of computer models that can deal with vast quantities of information, but these nevertheless cannot be used to predict events with certainty, a limitation ascribed to both the lack of available computing power and the lack of a full enough understanding of all the process involved (Randall et al. Citation2007, 601). Bhaskar (Citation2008, 141) called this inability to predict outcomes ‘an embarrassment – faced by non-experimental Humean scientists’ and he predicted their response as follows:

inevitably the Humean must address this weakness (of a lack of prediction) by falling back on: a) ‘the idea that our explanations are sketches to be filled out in the fullness of time’ (i.e. that we lack enough knowledge); or b) the idea that our explanations ‘are subject to an implicit ceteris paribus clause’ (i.e. there is likely to be too much variation between contexts because in practice all things are never equal)’. (Bhaskar Citation2008, 141–142)

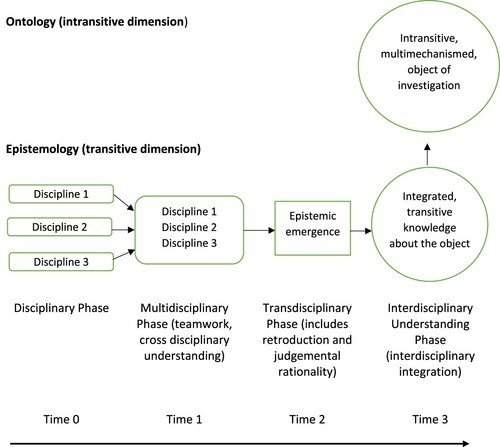

Figure 1. The phases of interdisciplinarity, modified from Bhaskar et al. (Citation2017, 124).

Judgemental rationality

Critical realists also realize that, because the social sciences necessarily deal with an open system, there is no possibility of achieving formal, statistical prediction. They, therefore, have a different way of assessing the quality of a scientific theory – not based on its ability to make predictions – which they term ‘judgemental rationality’ (Bhaskar Citation2016, 25). This approach to validity is a fallible one and it is based on the ability of the theory in question to explain more of the (complex) evidence than other competing theories. This is not a lax or trivial way to assess quality. Far from it, it is based on a truism first identified by Popper ([Citation1963] Citation2014), which is that the best way to identify truth is by falsification. When a model is unable to explain certain events, we know it is incomplete, and we can therefore say that it has been falsified. As Bhaskar explains:

And once you take that step (of assuming that models are about reality, not simply psychological projections onto the empirical level), you can see how falsification can be understood to be a rational process, because a theory is replaced as a false or inadequate account of a reality, and the new theory is accepted as a better, or deeper, or more beautiful, imaginative or creative account of the same reality. (Bhaskar in Singh, Bhaskar, and Hartwig Citation2020)

Retroduction

The rational process (retroduction) that gives us our theories, which we can then compare using judgemental rationality, is an inherent process of cognition (Bhaskar Citation2016, 30, 79). Furthermore, retroduction happens whether we are aware of it or not. However, community members are often better at retroductive theorizing than experts because, amongst other things, they are not bound by 'scientific' or disciplinary rules and therefore they are freer to be truly creative in the process of working out 'what happened'. Graduate scientists have been trained to avoid transcendental theorizing, since it is assumed to be untestable. Many of the greatest scientific minds have had to break with the taboo on transcendental thinking. Darwin, for instance, acknowledged that his theory of evolution went again scientific principles.Footnote4 By including the community in scientific research, one is allowing back the possibility of transcendent, transfactual, transdisciplinary thinking because these thinkers are, due to their naivete about empiricist science, not constrained by said science. This is how the actualist version of interdisciplinarity, such as that described by Gibbons and Nowotny, is held in place (keeps its credibility despite being based on questionable theory): its central tenets, which advocate against transdisciplinary thinking, are violated in practice when it allows scientifically ‘naïve’ communities to assess the problems. Bhaskar (Citation2016, 93) called this a There-Is-No-Alternative (TINA) compromise formation. In other words, mainstream versions of transdisciplinary ‘work’, despite their incorrect theory, because their practice allows retroductive theorizing. Just as, if you crush grapes and leave them in earthenware jars, you will get wine (usually), so, if you include non-experts in research aimed at finding ways to improve wellbeing, you are more likely to get better results than if you include only trained scientists. In both cases, a successful result can ensue without a full understanding of why the process works.

Mainstream versions of interdisciplinarity enable oppression

Therefore, in current mainstream versions of interdisciplinarity, retroductionFootnote5 happens, but it is not mentioned as part of the theory of what is happening. This is problematic in terms of ideological powerplay and ongoing oppression of some human beings by others. As Bhaskar (Citation2016, 93) explains “Understanding TINA compromise formation enables us to see how ideologies can render themselves plausible”. Essentially, if retroductive theories happen undercover, and there is, therefore, no formal way of choosing the best one (which in critical realism, we call judgemental rationality), then the retroductive theory most likely to be chosen as the one used to guide action will be the one that best protects the interests of dominant sections of society, to the detriment of other sections. Given that this is the case, then arguments about the philosophical understanding of interdisciplinarity are not merely academic; they have important consequences for human beings in real-life situations. For this reason, it seems imperative that we engage in a critical realist-style version of interdisciplinary research on issues related to health and well-being.

Summary of the articles in the issue

Having provided some background about the critical realist version of interdisciplinarity, I will now give a brief description of each of the articles in this health and well-being issue of JCR.

Hastings’ article (Citation2021) is about the causes of homelessness in Australia, and it is an exceptionally good example of critical realist research. She aims to understand why some families living in poverty become homeless and others do not, that is, she aims to discover the structures, contexts and mechanisms that could explain this. Her work is of particular interest because of the way that she makes substantial use of descriptive statistics ‘including transitions analysis, comparative statistical models across groups, and clustering of variables in nested models according to clusters of hypothesized mechanisms increasing risk’. She also draws on the empirical evidence from a broad range of interdisciplinary literature crossing over many methods and methodologies. She then synthesizes this multidisciplinary data by a process of transdisciplinary retroductive theorizing. Her work, therefore, demonstrates that critical realist interdisciplinary work does not require researchers to carry out all of the interdisciplinary research themselves. Such work rather requires that we engage with the work of other researchers, from other disciplines, and synthesize their work using transdisciplinarity. In this way, it is possible to achieve a proper synthesis of the disciplines, that is, true interdisciplinarity.

Deana Kanagasingam, Moss Norman, and Laura Hurd (Kanagasingam et al. Citation2021) use their analysis of the website of ‘Obesity Canada’ to encourage transdisciplinary dialogue amongst researchers with the objective of dismantling the entrenched disciplinary silos within obesity studies. They argue convincingly that understanding fat as a pathology does not serve the best interests of fat people and that fixating on obesity distracts researchers from examining other mechanisms, such as poverty and social exclusion, which may have a greater impact on health. They, therefore, propose ‘a shift in focus from weight to health, while promoting health in a non-moralistic, inclusive, and collectivist way’.

In the article, ‘Sustainable urban planning – what kinds of change do we need?’, Petter Næss (Citation2021) points out that effective policies that combine environmental and social sustainability must necessarily be ‘sharply at odds with key mechanisms inherent in the capitalist economy’. He suggests that a major reason why this conclusion is not obvious is that planning theory is currently largely anti-realist, that is, it is based on constructivism and hermeneuticism. He, therefore, implores us to move away from anti-realism and ‘disciplinary tunnel vision’ towards a critical realist version of interdisciplinarity. In so doing, he argues, it will be clear that we need to shift ‘from growth to degrowth, from inequality to equality, and from capitalism to eco-socialism’.

Ruth Elizabeth Edwards and Judith Burton (Citation2021) make excellent use of the critical realist concept of layered reality in their article ‘Young women’s recovery from problematic alcohol use: a critical realist reconceptualization’. This concept, of the layers of reality, allows them to link together theories that look at the different layers of constraining and enabling reality relevant to young women in recovery. They highlight the factors that negatively impact habitus and conscious reflexivity and arrive at suggestions that may improve the situation. In particular, they identify the role of advertising, culture and the women’s social networks in creating a habitus conducive of excessive consumption of alcohol. They argue that through a process of internal conversation, the women are able to create their own versions of habitus (they, therefore, assume that the women have more agency than is typically given to them in Bourdieu’s version of habitus). However, they argue that, to support this empowering process of reflexivity, the women need access to better information about the dangers of alcohol use. Furthermore, they argue that through the process of improving access to this information, it is conceivable that the alcohol consumption behaviour of the women’s social networks may also be positively transformed.

The article ‘Democracy in practice? The Norwegian Public Inquiry of the Alexander L. Kielland North-Sea oil platform disaster’ by Weihe and Solbakken (Citation2021) perceptively describes the process by which non-expert viewpoints that challenge the status quo are denied respectability because the theory of mainstream science has no ontology for multimechanismicity and no place for retroduction. This article specifically illustrates how the opinions of the survivors of the Alexander L. Kielland North-Sea oil platform disaster were side-lined, which jeopardized the potential for the Inquiry to arrive at suggestions that might help avoid future similar disasters. Weihe's and Smith-Solbakken‘s central message is that democracy that is not underpinned by something like a critical realist version of science is seriously compromised; and that, without critical realism, gestures towards democracy, such as interviewing the non-experts for their views, are simply window-dressing.

The brutal effect on health and well-being of neoliberalism is discussed by Priscilla Alderson (Citation2021) in her article ‘Health, illness and neoliberalism: An example of critical realism as a research resource’. She considers a wide range of topics, but one that merits particular mention is her discussion about how the absence of interdisciplinarity – as found in Random Controlled Trials (RCTs) – allows researchers to avoid making discoveries that might challenge oppressive socioeconomic and political structures. She also argues that ‘Even in small research studies that concentrate on particular aspects of health and illness, such as the experiences of people with diabetes, the four planes of social being can help to broaden, explain and contextualise the research.’

Finally, in his paper, ‘Preventing mental disorder and promoting mental health: some implications for understanding wellbeing’, David Pilgrim (Citation2021, this issue) also makes good use of the critical realist concept of four-planar social being to consider the debates surrounding the prevention of mental disorder and the promotion of mental health. In so doing, he develops a holistic understanding of mental health and mental disorder which is able to accommodate the complexity of the interacting causal mechanisms.

Conclusion

Health and well-being research has moved through many phases or ‘fashions’ over the years, from the strict medical model which reduced health problems to biology, through to the socioeconomic model which reduced health problems to the social and economic context, to the language (Foucauldian) model, in which health problems were reduced to language-based social constructions (Bhaskar and Danermark Citation2006). The biopsychosocial model acknowledges the need to integrate all of these approaches in an interdisciplinary way, but as this Editorial has demonstrated, there is little available mainstream advice on how to accomplish this integration. Critical realism is, in my opinion, the only approach to interdisciplinarity that provides practical guidance about how to achieve interdisciplinarity, and the articles on health and well-being research presented in this Issue are evidence of the effectiveness of this guidance. It is my sincere hope that these articles will inspire a new generation of health and well-being researchers. By giving them the tools to step beyond the limitations imposed by current conceptions of interdisciplinarity, there is every chance that they will truly excel in providing the research needed to lead humanity towards a healthier and happier future.

Notes

1 We nevertheless understand that human well-being is dependent on the well-being of the environment too.

2 Some might object to my suggestion that Max-Neef’s position has just two layers of reality, but by my understanding, his many layers are based on the dualism of categories typical of phenomenal/noumenal, objective/subjective positions. Therefore, I place his norms, values and purposes layers under the umbrella of the subjective layer.

3 Retroductive theorising involves ‘imagining a model of a mechanism that, if it were real, would account for the phenomenon in question’ (Bhaskar Citation2016, 30, 79).

4 Darwin (Citation1857) said in a letter to Asa Gray “I am quite conscious that my speculations run quite beyond the bounds of true science”.

5 In addition to retroduction, critical realists also use retrodiction, which is the use of previously attained theories to explain the situation. In practice, interdisciplinarity often requires a mixture of retroduction and retrodiction (Bhaskar Citation2016, 79–82).

References

- Alderson, Priscilla. 2021. “Health, Illness and Neoliberalism: An Example of Critical Realism as a Research Resource.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 542–556. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1995689

- Bhaskar, Roy, and Berth Danermark. 2006. “Metatheory, Interdisciplinarity and Disability Research: A Critical Realist Perspective.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 8 (4): 278–297.

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, Roy, and Mervyn Hartwig. 2016. Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism. London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, Roy, Berth Danermark, and Leigh Price. 2017. Interdisciplinarity and Wellbeing: A Critical Realist General Theory of Interdisciplinarity. London: Routledge.

- Darwin, Charles. 1857. “Letter to Asa Gray.” Darwin Correspondence Project. June 18. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-2109.xml.

- Edwards, Ruth Elizabeth, and Judith Burton. 2021. “Young Women’s Recovery from Problematic Alcohol Use: A Critical Realist Reconceptualization.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 491–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1917245

- Gibbons, Michael, and Helga Nowotny. 2001. “The potential of transdisciplinarity.” In Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving Among Science, Technology, and Society, edited by J. Thompson Klein, W. Grossenbacher-Mansuy, R. Häberli, A. Bill, R. W. Scholz, and M. Welti, 67–80. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Hastings, Catherine. 2021. “A Critical Realist Methodology in Empirical Research: Foundations, Process, and Payoffs.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 458–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1958440

- Kanagasingam, Deana, Moss Norman, and Laura Hurd. 2021. “Illuminating the Ethical Tensions in the Obesity Canada Website: A Transdisciplinary Social Justice Perspective.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 474–490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1992733

- Katz, Solomon H., Fritz Maytag, and Miguel Civil. 1991. “Brewing an Ancient Beer.” Archaeology 44 (4): 24–33.

- Kelly, Rachel, Mary Mackay, Kirsty L. Nash, Christopher Cvitanovic, Edward H. Allison, Derek Armitage, and Aletta Bonn. 2019. “Ten Tips for Developing Interdisciplinary Socio-Ecological Researchers.” Socio-Ecological Practice Research 1 (2): 149–161.

- Klein, Julie Thompson. 2001. Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving Among Science, Technology, and Society: An Effective Way for Managing Complexity. New York: Springer.

- Lindvig, Katrine, and Line Hillersdal. 2019. “Strategically Unclear? Organising Interdisciplinarity in an Excellence Programme of Interdisciplinary Research in Denmark.” Minerva 57 (1): 23–46.

- Max-Neef, Manfred A. 2005. “Foundations of Transdisciplinarity.” Ecological Economics 53 (1): 5–16.

- Næss, Petter. 2021. “Sustainable Urban Planning–What Kinds of Change do we Need?” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 508–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1992737

- Nicolescu, Basarab. 2002. Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity. Albany: Suny Press.

- Nowotny, Helga. 2005. “The Increase of Complexity and Its Reduction: Emergent Interfaces Between the Natural Sciences, Humanities and Social Sciences.” Theory, Culture & Society 22 (5): 15–31.

- Nowotny, Helga. 2017. An Orderly Mess. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Pilgrim, David. 2021. “Preventing Mental Disorder and Promoting Mental Health: Some Implications for Understanding Wellbeing.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 557–573. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1966603

- Popper, Karl. (1963) 2014. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Price, Leigh. 2014. “Critical Realist Versus Mainstream Interdisciplinarity.” Journal of Critical Realism 13 (1): 52–76.

- Randall, David A., Richard A. Wood, Sandrine Bony, Robert Colman, Thierry Fichefet, John Fyfe, Vladimir Kattsov, et al. 2007. “Climate models and their evaluation.” In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC (FAR), 589–662. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (2): 155–169.

- Singh, Savita, Roy Bhaskar, and Mervyn Hartwig. 2020. Reality and Its Depths. Singapore: Springer.

- Stehr, Nico, and Peter Weingart, eds. 2000. Practising Interdisciplinarity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Wallin Weihe, Hans-Jørgen and Marie Smith-Solbakken. 2021. “Democracy in Practice? The Norwegian Public Inquiry of the Alexander L. Kielland North-Sea Oil Platform Disaster.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (5): 525–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1995688