ABSTRACT

Realist evaluation has gained prominence in the field of evaluation in recent years. Its theory-driven approach to explaining how and why programmes work or not makes it attractive to many novices, early career researchers, and organizations implementing various programmes globally and relevant to policymakers and programme implementers. While realist evaluation seeks to be pragmatic, adopting principles and methods that can be used to help focus an evaluation, its deep ontological and epistemological foundations make its application in real-life situations challenging. In this paper, we seek to unpack the key tenets scaffolding the practical application of realist evaluation. Although Pawson and Tilley foreground realist evaluation in applied scientific realism, we argue that an amalgam of scientific and critical realist principles underpins realist evaluation. We unpack these principles and illustrate how they fit into each other to provide a cogent theoretical foundation for realist evaluation.

Introduction

Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) introduced realist evaluation through their seminal work Realistic Evaluation as a practical approach to realist-informed research. Since then, this proposed approach to evaluating complex interventionsFootnote1 has been used in many fields of evaluation sciences. Realist evaluation is a form of theory-driven evaluation characteristically set apart by its explicit explanatory nature and philosophical foundation underpinnings regarding underlying (social) structures and generative (social) mechanisms (Renmans et al. Citation2022). Although realist evaluation is strongly underpinned by a philosophical metatheory (Realism), like other evaluation approaches, it seeks to be pragmatic, adopting principles and methods that can be used to help focus an evaluation. Nevertheless, difficulties pinpointing realist evaluation’s philosophical and methodological foundations, especially among novice realist researchers, have been noted (Marchal et al. Citation2012). Therefore, identifying the underlying realist principles and translating their practical implications for realist evaluators is critical to improving its uptake and robust application.

Realist evaluation focuses on unravelling the programme theory guiding how and why a programme works or not (Mukumbang et al. Citation2016). The programme theory’s explanations should refer to unobservable entities (mechanisms) whose behaviour is responsible for the observation made after an intervention is implemented. Realist evaluation aims to explain the processes involved in introducing an intervention in a particular context (with certain characteristics and groups of actors operating within it), and the outcomes observed after the intervention implementation (Porter and O’Halloran Citation2012). It is, thus, particularly relevant to evaluations involving human services, social policies, health interventions, and Implementation Science outcomes (Jagosh Citation2020) and seeks to unpack ‘what works, for whom, in what respects, to what extent, in what contexts, and how?’ (Pawson and Tilley Citation2004).

Considering that scientific work and practice are embedded within a philosophy of science or meta-theory (Allana and Clark Citation2018), realist evaluation is also entrenched in realist ontological and epistemological foundations. Therefore, for the proper application of realist evaluation, there is a need to address the weaknesses and contradictions in the meta-theory guiding realist evaluation (Porter Citation2015a). Many researchers conducting realist evaluation, including the RAMESES II study for developing guidance and reporting standards for realist evaluation, situate realist evaluation in the general philosophical position of Realism (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2015). Scientific realism and critical realism are the two prominent forms of Realism. Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) specifically situate realist evaluation in scientific realism. Because scienfic realism and critical find their roots in Realism they thus have a lot in common. Given the similarities shared between scientific realism and critical realism, critical realism’s contribution to realist evaluation remains a source of confusion and frustration among many Ph.D. students and early career researchers conducting realist evaluation. To this end, this paper aims to identify fundamental principles of scientific realism and critical realism underpinning realist evaluation and explain how they contribute to retroductive theorizing in realist evaluation.

Realist evaluation and scientific realism

Scientific realismFootnote2 constitutes a family of doctrines about the aim of science (Sankey Citation2001). What most characterizes scientific realism as a form of Realism is its metaphysical doctrine about the external world. Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) explicitly reported that their ‘contribution to evaluation is distinctive in that it is the first to rest on realist principles’ (55). They situated realist evaluation specifically in scientific realism and described it as applied scientific realism. Indeed, they have described their version of evaluation as a ‘scientific realist evaluation’ (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997a). In chapter three of their book Realistic Evaluation, Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) outlined some fundamental principles of the scientific realist paradigm guiding their proposed realist evaluation.

To the novice practitioner interested in realist evaluation, Pawson and Tilley’s (Citation1997a) explicit insinuation that realist evaluation is predominantly informed by scientific realism and Pawson’s (Citation2013) eventual distancing from some of the works of Roy Bhaskar, would seem that scientific realism predominantly informs the practice of realist evaluation. More recently, Pawson’s choice of drawing from Bhaskar’s work in the sciences in the development of realist evaluation has been questioned (de Souza Citation2022). Pawson’s straying from Roy Bhaskar’s works seemingly stems from a concern that, Bhaskar’s outpourings increasingly adopted a normative and emancipatory nature. It was highlighted that Bhaskar’s work in the human sciences, instead, would be more suited to the social science where programme evaluation (Rossi, Lipsey, and Henry Citation2018), permits more to be explained and critiqued. Consequently, evaluation practitioners suggests that Bhaskar’s philosophical works did not delve into scientific realism. This is far from true as Pawson (Citation2013) himself, acknowledges drawing from Bhaskar’s ‘A Realist Theory of Science’ and Archer’s ‘Realist Social Theory’. These two key figures were, and have been, heavily involved in developing what has become more popularly known as critical realism.

Critical realism

Critical RealismFootnote3 came to the fore during the paradigm wars of the 80s and 90s when contestations began surfacing between proponents of the different schools of philosophical thought, on which would be more practical to inform research practice (Gage Citation2016; Oakley Citation1999). The contestations were clarion calls to rethink the scope of what was counted as ‘acceptable’ and ‘scientific’ research practices. Crudely speaking, the Positivist understanding of natural science has historically maintained that the methodology adopted in the study of natural and social sciences are unified in adherence to positivist principles, and that the objects of study in both disciplines can be understood and examined in the same manner (Keat Citation1971) In North America and the United Kingdom, however, the anti-naturalism shifts initiated by social constructionists, supported a cleavage in the research methods adopted in the social sciences.

This cleavage, however, was not without problems. The essential thrust of the social constructionist viewpoint is that ‘One can only change the narratives by changing the discursive conventions by which they are created and interpreted’ (Harré Citation2006, 26). Disquiet occurred about how some forms of social constructionism worked to undermine certain longstanding understandings by (1) relativizing foundationalists’ claim to certainty and positivists’ claim to objective truth; (2) making possible the rejection of humanism on grounds that the politics embedded in language challenged the possibility of autonomy and unitary identities; and (3) rejecting the probability of any objectivism in the idea of representation (Alvesson Citation2002; Parker Citation1998b). Opponents of social constructionism were concerned that it would theoretically allow for extreme forms of relativism. Proponents, in comparison, were apprehensive about how to make judgments between the multiple perspectives available and where agency might come into play within the perspective (Burr in [Parker Citation1998a]).

Archer (Citation2020) positioned her work on Realist Social Theory as complementing Bhaskar’s (Citation1998) social ontological work in ‘The Possibility of Naturalism’. While the latter has identified admissible constituents and concepts to address the social world, Realist Social Theory (Archer Citation1995) proceeds to order and connect these constituents and concepts into a meaningful framework for explaining social change and reproduction (social morphogenesis). Where there has been more agreement, is the possible influence Margaret Archer’s work on Realist Social Theory can have on realist evaluation.

The moderating effect is that Critical Realism is evident in the non-Positivist naturalism position it adopted, and the important distinction it makes between judgmental and epistemic relativism. Instead of advocating the need for a cleavage in the approaches used to inquire into the nature of natural and social objects thereby allowing questions and contestations to be raised about what does or does not count as ‘evidence’, ‘scientific’, and/or ‘rigorous’, Critical Realism maintains that both natural and social objects can be studied scientifically. Notably, Bhaskar (Citation1998) asserted that the naturalism proposed by Critical Realism differs from that implied in the positivist version of naturalism in that,

… the predicates that appear in the explanation of social phenomena will be different from those that appear in natural scientific explanations and the procedures used to establish them will in certain vital respects be different too (being contingent upon, and determined by, the properties of the objects under study); but the principles that govern their production will remain substantially the same … because social objects are irreducible to (and really emergent from) natural objects, and so possess qualitatively different features from them, they cannot be studied in the same way as them, [but] they can still be studied ‘scientifically’. (Bhaskar Citation1998, 22)

… movement at any one level of inquiry from manifest phenomena to the structures that generate them. It shows that experimental and practical activity entails an analysis of causal laws as expressing the tendencies of things, not conjunctions of events (‘epistemology’); that scientific discovery and development entails that scientific inferences must be analogical and retroductive, not simply inductive and/or deductive (‘logic’); and that the process of knowledge-production necessitates a conceptual system based on the notion of powers (‘metaphysics’) … [for the social sciences] things are viewed as individuals possessing powers (and as agents as well as patients). And actions are the realization of their potentialities. Historical things are structured and differentiated (more or less unique) ensembles of tendencies, liabilities and powers; and historical events are their transformations. (Bhaskar Citation1998, 19)

Towards a cogent theoretical foundation for realist evaluation

An amalgam often informs scientific inquiries of principles and practice (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997b). Evangelopoulos (Citation2013) reported that, while scientific realism focuses on the objectivity aspect of science – reality consists of an independent object whose knowledge is the ultimate objective of all scientific activities, critical realism focuses on the social dimension of science, which also captures the scientific activities as the historical product of the human society. Owing to their seemingly different fundamental goals, scientific realism and critical realism offer different but complementary perspectives to inform realist evaluation. Indeed, they share similar understandings relating to the existence of a mind-independent reality, the existence of the unseen, upward and downward causation, stratified reality, emergence, the embrace of multiple methodologies, and the importance of theory in science (Brekke et al. Citation2019). Consequently, many researchers pilfer various aspects of scientific realism and critical realism to inform their realist evaluation methodology. Porter (Citation2017) confirms that Pawson developed the realist evaluation approach through erudite eclecticism.

While Pawson and Tilley ground realist evaluation in scientific realism, attempts have been made to examine the Critical Realist roots of realist evaluation (Porter Citation2015c). In agreement with Porter that realist evaluation requires a cogent theoretical foundation, we unpack the ontological and epistemological positions of scientific realism and critical realism regarding their contributions towards realist evaluation methodologies. Such explication will provide a basic understanding of realist evaluation to the non-realist audience and a gentle introduction to novice and early career researchers willing to employ realist evaluation methodologies or undertake a realist evaluation. Consequently, current philosophical discussions around scientific realism and critical realism will not be the focus of this paper. Instead, it will be about the relative merits of the two realist positions in evaluation research.

We focus on capturing those aspects of the two forms of Realism that are generally acceptable in the extant literature and unpack their methodological implications for realist evaluation. We have organized this discussion accordingly. First, we will discuss some central tenets of Realism and how they are accentuated in scientific realism and critical realism in a general manner and then explain how these tenets contribute to retroductive theorizing in realist evaluation. Then, we will conceptualize their contributions toward a cogent epistemological foundation of realist evaluation.

Mind-independent reality

Mind-independent reality means that the world’s existence, nature, and structure are independent of human thought, language, conceptual activity, and perceptual experience (Sankey Citation2021). It has properties and structures that can be known through empirical inquiry (Brekke et al. Citation2019). Therefore, mind-independence is a way of saying something is real, objective, and truly exists, not just the product of our imaginations or other cognitive processes (Khalidi Citation2016). For example, the generative mechanisms of the outcome of a healthy eating intervention on pre-diabetic individuals will remain what they are, irrespective of our perspective of the programme. The way the intervention will play out after its implementation and the generative mechanisms involved are ontologically distinct from the observed outcomes. They do not depend on the researcher or the way the researcher thinks, or tools and methods used – ontological objectivity. To this end, the goal of realist evaluation is to determine the nature of the intervention – how and why the intervention works or not, irrespective of how and why we think they work. Realist evaluation is, therefore, proposed as one practical activity among others, which allows us to take a closer look at the relationship between practice, meaning, concepts, and language and the underlying mechanisms and structures constituting reality vis-à-vis a particular phenomenon or intervention. Although language, and consequently conceptualization, stands out as one of our most essential instruments for scientific research, reality does not depend on them, and they do not determine what is real (Danermark, Ekström, and Karlsson Citation2019).

Semantic notion

The second principle of scientific realism relates to the relationships between theories and the world – semantic notion. The semantic notion of scientific Realism relates to the idea that reality (although mind-independent) can be effectively captured through scientific theories. Bhaskar (2013, 16) calls these the transitive objects of knowledge ‘the raw materials of science – the artificial objects fashioned into items of knowledge by the science of the day. They include the antecedently established facts and theories, paradigms and models, methods, and inquiry techniques available to a particular scientific school or worker’. Scientific realism does not simply accept that there is a mind-independent world, but they try to capture the truth about the nature of reality. Therefore, scientific theories are used to describe this mind-independent reality. Capturing reality should not be solely achieved through measurement, observations, intentions, information, social norms, or any other epistemically loaded or anthropocentric term. Instead, these anthropocentric measurement approaches should seek to unpack the underlying causal processes of our observations. Bhaskar and Lawson (Citation2013) also demonstrates ‘how the intelligibility of experiments presupposes that reality is constituted not only by experiences and the course of actual events, but also by structures, powers, mechanisms and tendencies – by aspects of reality that underpin, generate or facilitate the actual phenomena that we may (or may not) experience, but are typically out of phase with them’ (Bhaskar and Lawson Citation2013, 5).

To elicit programme theories, therefore, the realist evaluator embarks on the process of retroduction, a form of retrospective theorizing, which entails moving from the observed outcomes of the intervention to reconstruct the conditions for the outcomes to occur by unearthing the underlying generative mechanisms and structures (Fletcher Citation2017; Meyer and Lunnay Citation2013; Mukumbang, Kabongo, and Eastwood Citation2021). Retroduction as applied in realist evaluation involves exploring the intervention’s effects and then working backward to unearth the generative mechanisms responsible for producing the results (Jagosh Citation2020). Retroductive theorizing in realism-informed inquiries requires the realist evaluator to remain faithful to the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of realism (Mukumbang Citation2021), which have been situated in scientific realism (Jagosh Citation2020) and critical realism (Downward and Mearman Citation2007).

Scientific Realism posits that our scientific theories are true or false based on the best scientific knowledge. We should consider our scientific theories true – the entities they postulate as real, not merely as ‘useful’ (Chernoff Citation2007). Theoretical explanations in scientific realism go beyond the observable world captured through anthropocentric approaches and other observational measurements to accommodate knowledge about the unobservable (Allzén Citation2021). The theoretical discourse of scientific realism thus focuses on both the observable and the unobservable entities. To justify the centrality of observable and unobservable objects to theoretical discourse, Scientific Realism typically invokes inference to the best explanation or theories (Allzén Citation2021). For these theories to be accurate or referential, the unobservable entities they propose must exist, a condition described as realist correspondence of truth. Realist correspondence of truth submits that a proposition is true if it corresponds to an objectively existing state of affairs, whether or not we believe that the state of affairs exists (Sankey Citation2021).

Epistemic notion

The epistemic notion of scientific realism suggests that the best and most credible scientific theories represent an approximation of reality (truth). These theories could emanate from our common sense, which our interactions with the physical world can inform through our senses (Sankey Citation2001). Therefore, the reality about everyday objects and our epistemic access to such objects provide the starting point for common sense or abductive realist components of the argument for scientific realism (Sankey Citation2001). Scientific realism takes common sense or abduction as a starting point toward obtaining more robust scientific theories through epistemic access using our senses. Nevertheless, these theories should only be taken at face value as they are only truth approximating, considering that they can be true or false – fallible (Brekke et al. Citation2019). In Chapter 3 of A realist Theory of Science, Bhaskar and Lawson explain that explanatory science,

seeks to account for … an experimentally produced event pattern in terms of a (set) of mechanism(s) most directly responsible. Producing this explanation will involve drawing upon existing cognitive material and operating under the control of something like a logic of analogy and metaphor, to construct a theory of mechanism that, if it were to work in the postulated way, could account for the phenomenon in question. The reality of the mechanism so retroduced is subsequently subjected to empirical scrutiny, and the empirical adequacy of the hypothesis maintained compared to that of competing explanations. (Bhaskar and Lawson Citation2013, 5)

Following this initial abductive theorizing, retroductive thinking is adopted to investigate the hypothesized generative mechanisms to confirm or challenge the initial abductively generated programme theory. These retroductively obtained theories may be close to or considered an approximation of how and why the programme works (or not). Programme theories may not embody mechanisms in the truest ontological sense. Nevertheless, subsequent programme theory development and testing cycles may increase our knowledge of these generative mechanisms.

Levels of reality

Bhaskar (Citation1975), in his conceptualization of science as a social activity, described Realism as having three levels: Real, Actual, and Empirical. Although scientific Realism does not explicitly classify reality as constituting of these three levels, it suggests that reality comprises of both observable and unobservable entities. Critical Realism, conversely, explicitlyillustrates where these observable and unobservable entities can be found. Bhaskar (Citation1975) used the following analogy () to describe observable and unobservable entitles, explicating our access to information on these levels.

Table 1. Three levels of reality (Bhaskar Citation1975).

According to Bhaskar’s (Citation1975) classification, the Domain of the ‘Real’ contains both observable/measurable entities (experiences) and unobservable entities (causal entities such as mechanisms). While these causal entities cannot be observed directly, their effects can be captured and described using empirical methods, and their existence is theorized. Research activities are purported to capture some events easily, and these events reported as experiences are placed at the ‘Empirical’ level. While some of these events can be captured using our observation methods and empirical activities, not all these events get experienced so they go uncaptured even with our best observation methods (Brekke et al. Citation2019). Whether captured or not, events are generally considered to be situated at the level of the ‘Actual’ as they represent things that ‘actually’ happened. Therefore, real structures and causal mechanisms exist independently of actual patterns of events necessitating the need to undertake scientific activities to make sense of their operations.

When a social intervention such as an intervention to reduce gender-based violence is implemented, various social mechanisms (such as willingness to change, love, and emotional intelligence) and intervention mechanisms (such as understanding relationship dynamics) are triggered based on the interactions of different agents (different genders) acting within social structures such as cultural values and family dynamics. These structures and mechanisms are found in the realm of the Real, and the goal of the realist evaluator is to unearth them. When these interactions occur, events and nonevents occur. Improved understanding and cooperation among couples can lead to demi-regularities or observations such as reduced incidence of gender-based violence and other unnoticed events that can be captured in the ‘Actual’. The actors’ experiences after implementing the intervention can be captured empirically using various research methods such as interviews and surveys to explain the (un)changed pattern of behaviour, which occurs at the ‘Empirical’. The role of the realist researcher is to use the information captured at the empirical to excavate those mechanisms and context conditions that combine to explain how and why the interventions work or not.

Transitive and intransitive entities

The social activity of unravelling the underlying generative mechanisms and real structures generating the observed outcome(s) of intervention brings to the fore the notions of transitive and intransitive entities in critical realism. The transitive entities (entities amenable to alteration by human action) of sciences represent the outcomes of the activities of science through empirical activities. For example, the knowledge, models, and theories derived from research activities to understand how and why an intervention works constitute transitive objects. This means that as time goes on, our understanding of how and why an intervention works or not might change as better methods of capturing experiences and observations become available. The implication is that those programme theories elicited from a realist evaluation cycle are always provisional and partial. Still, they can be improved as more evidence becomes available (MESH Citation2017).

Intransitive entities (entities that human actions cannot change), on the contrary, represent laws and properties of the world independent of our knowledge of them and efforts to understand them. For instance, culture and beliefs exist independent of our knowledge of them. Still, they are just as ‘real’ as physical processes, and they have tangible effects even if they are not directly observable and need to be inferred from evidence (MESH Citation2017). This distinction between what critical Realism calls the transitive (the changing knowledge of things) and the intransitive (the relatively unchanging things which we attempt to know) has implications for realist evaluation – our efforts to understand how and why an intervention works or not can be finite. The programme theories obtained from a realist evaluation inquiry can inform another realist evaluation cycle to capture the existing mechanisms and structures irrespective of our knowledge of their existence. The notions of transitive and intransitive objects of Critical Realism highlight the intelligibility of scientific understanding, particularly the fallibility and transformation of human knowledge. For example, while our understanding of how and why an intervention works or not can change over time as more evidence becomes available through empirical investigations, the underlying structures and mechanisms that interact to produce the observed outcome most often remain unchanged – more become unveiled as time goes on or the nature of the intervention changes with time.

Emergence – the whole is greater than the sum of its parts

Another central element of critical Realism is emergence. Emergence occurs when a whole possesses one or more emergent properties (Elder-Vass Citation2010). Unobservable entities are structured, and these structures are nested within other structures, for example, family dynamics nested within cultural or religious practices. These entities are usually unobservable, and their operations depend on situational conditions created by complex interactions with other things (Brönnimann Citation2021). The occurrence of novel qualities from the interactions of these existing entities is described as emergence. Some of the causal properties of the existing entities emerge from structured relations between their constituent entities (Sorrell Citation2018). The novel qualities that emerge are not always the sum of the parts of the interacting entities, and they can also not be reduced to the entities from which they arise (Brekke et al. Citation2019). Therefore, ‘An emergent property is not possessed by any of the parts individually, and that would not be possessed by the full set of parts in the absence of a structuring set of relations between them’ (Elder-Vass Citation2010). Social interventions have emergent properties, that is, possessing causal entities, which may result in a particular outcome under certain conditions. Therefore, the realist evaluator’s role is to unveil the causal mechanisms and those conditions under which the causal entities of the intervention are triggered to produce the outcomes (intended or unintended).

Emergence is hierarchical, occurring at different levels of reality: molecular, chemical, organisms, groups, and society. Entities at a lower level (molecular) can create conditions for unfolding new entities at a higher level. Sayer (Citation2000) illustrates this idea by highlighting that ‘social phenomena are emergent from biological phenomena, which are emergent from chemical and physical strata’ (13). While other entities may emerge from lower strata, they are not reducible to those strata and, therefore, still need to be researched in the strata in which they operate to explain their operation (Mukumbang Citation2021).

Open and closed systems

The notions of open and closed systems elucidate the concept of emergence. From an empirical point of view, critical realists characterize the social world as an open system (Fleetwood Citation2017). Critical Realism suggests that the world is an open system with a constellation of structures, mechanisms, and other entities responsible for the observable patterns of events. Bhaskar (Citation1989) explained that human capacity and agency are omnipresent and unlimited in their ability to alter their environment. The agents’ interactions with social structures give rise to observable and unobservable patterns occurring as events (demi-regularities) in the ‘Actual’. The demi-regularities are usually consistent with regular habits and behaviours, but these events or behavioural patterns are never deterministic or stochastic event regularities (Fleetwood Citation2017). This is because, under countervailing conditions, other unintended or alternative behaviours could be observed – contrastive (Lawson Citation2001). Therefore, in critical Realism, an open system is about (ir)regularities in the flux of events and states, not systems (Fleetwood Citation2017).

Considering reality as an open system in critical Realism has implications for systems thinking in realist evaluation (de Souza Citation2022). Pawson et al. (Citation2005), while drawing from Archer’s realist social theory, acknowledged that programmes are parts of open systems or embedded in multiple social systems. As such, social interventions are considered as ‘complex systems thrust amidst complex systems’ (Pawson Citation2006, 25). The adoption of systems thinking approaches in realist evaluation, thus, captures the notion of complexity by foregrounding relationships in wholes rather than by isolating parts (de Souza Citation2022), which is the premise of irregularities and demi-regularities.

Generative view of causation: agent-structure relations

Within open systems are the activities of agents (thoughts and actions taken by people) interacting with structures (organized social institutions and patterns of institutionalized relationships). The concept of social morphogenesis proposed by Archer (Citation1995, Citation2020) deals with the relationship between structures and agents in critical social realist terms. According to Archer (Citation1995), agents in the past organized and constructed the various structures – social, economic, cultural, and political systems – that make up our society. These social structures are causally effective, having generative powers that differ from agents’ causal powers (Elder-Vass Citation2008). The generative powers that the agents possess interact with those of the social structures to determine the agents’ actions, thus the notions of emergence and open systems (Bhaskar Citation2009). For example, multiple stakeholders are involved in any given intervention, each with their interpretation of the structures governing the interventions and ideas held within the intervention modalities. In Bhaskar’s (Citation2009) agential movement, the agent’s actions contribute to reproducing and transforming the structure(s) concerned, consequently leading to social change.

Elder-Vass (Citation2010) clarified that the causal powers of structures (and interventions in the case of realist evaluation) are only activated when agents act upon them. Therefore, the product of the causal influence of structures is highly contingent on the dispositional properties of the agents. Programme mechanisms are a sub-set of social mechanisms (structures) in that agents have consciously created them to alter the interpretations and actions of other agents (Porter Citation2015b). As such, the characteristics or modalities of interventions are only part of the relevant entities. The social processes involved in its implementation must be understood to describe how the outcomes are achieved (Porter and O’Halloran Citation2012). The implication is that the mechanisms introduced by an intervention are not the only ones in operation. To explain observed intervention outcomes, it is also necessary to consider the context in which the intervention is introduced (Porter Citation2015a). To this end, Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) proposed the context + mechanism = outcome as a heuristic tool to formulate realist programme theories. The context here relates to ‘ … the relational and dynamic features that shape the mechanisms through which the intervention works, assuming that context operates in a dynamic, emergent way over time at multiple different levels of the social system’ (Greenhalgh and Manzano Citation2021, 583).

The methodological implication of the agent-structure relationship for realist evaluation is that critical realism accepts the categorical distinction between social structure and agency and their corresponding generative powers and potentials (Porter Citation2015b). Bhaskar explicitly distinguished the roles of agency and structure while establishing their relationship. Similarly, Archer found the relationship between agents and structures by exploring their roles in changing social reality. Bhaskar suggested that ‘agents have intentions and plans, which determine their actions while structures govern the reproduction and transformation of social activities’ (Bhaskar, Citation1989, 79). This suggests that mechanisms can be found at the level of the agent, structures, and the interaction between the two. Conversely, Pawson regards social mechanisms as a combination of agency and structure, focused on people’s reasoning (cognitive or emotional) and choices (Porter Citation2015b). According to Pawson and Tilley (1997), programmes alone do not cause changes but rather how agents respond to the resources, ideas, and practices that those programmes introduce (programme ‘mechanisms’) to create programme outcomes. Critical realism recognizes that structural and cultural situational mechanisms create enabling and restricting conditions. Using the critical realist lens to programme evaluation also suggests that social interventions are stimulative for specific actions and provide conditions that may be less connected with the agency’s intentions (Brönnimann Citation2021). Other outcomes are observed when social programmes or interventions are introduced in the context of these structural and cultural situational mechanisms.

Tenets of critical realism and scientific realism, and retroductive theorizing

Retroductive theorizing identifies and conceptualizes the underlying causal entities, structures, and mechanisms to explain social activities (Jagosh Citation2020; Mukumbang Citation2021). As applied in realist evaluation, retroductive theorizing is a retrospective approach to unearthing the generative (social) mechanisms and structures responsible for the outcomes observed when an intervention, programme, or policy is implemented in a particular setting.

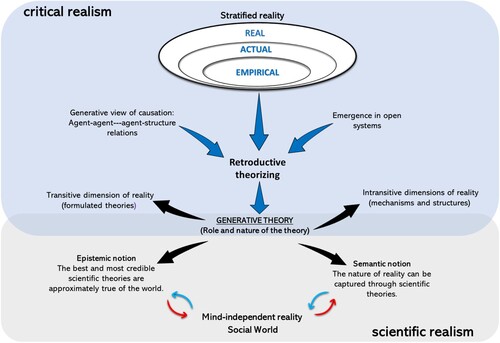

The point here is to illustrate how the different epistemological principles of critical realism and scientific realism discussed in the section above contribute toward retroductive theorizing in realist evaluation. illustrates the visual contributions of the epistemological principles of critical realism and scientific realism, to realist evaluation, with retroductive theorizing serving the purpose of ‘re-vindicating ontology by taking stock of and transcending the social construction of facts and evidence’ (Jagosh Citation2020).

Figure 1. Contributions of the different realism tenets to retroductive theorizing and the nature of the generative theory.

Note: The blue arrows are tenets related to the contributions toward theory formulation. The black arrows are related to tenets describing the nature of the formulated theories.

In addition to illustrating the ontological and epistemological contributions of both forms of Realism to retroductive theorizing, we have added in the methodological implications of these tenets for realist evaluation. Critical realist tenets predominantly contribute towards the social activities of eliciting the theories, while the scientific realist principles relate to the validity of the theories developed. This conception by Brönnimann (Citation2021) illustrates the movement from Critical realist principles to Scientific realist principles within our conceptualization (). (1) ‘Explication of Events’ by collecting information about observed empirical outcomes of the intervention – the principle of stratification of reality. (2) Based on the observed outcomes, identify structures, mechanisms, and their relevant context – open system and emergence principles. (3) Based on these conceptualizations, retroduce multiple viable mechanisms responsible for the observations – the generative view (principle of agent-agent – agent structure relationships). (4) Engage in empirical corroboration, which includes judgmental rationality (the critical realist concept relating to the possibility of making claims to knowledge and truth) to validate the hypothesized mechanisms – transitive and intransitive dimensions of reality leading to understanding the epistemic notion of Scientific Realism. Throughout this process, the application of triangulation and multi-methods are encouraged to accumulate richer data – the semantic notion of scientific realism. Validating or invalidating these hypothesized mechanisms against the original data and case reality aligns, thus supporting the thesis of the correspondence between theory and social reality and truth approximation represented by the epistemic notion of Scientific Realism. A detailed contribution of the Critical Realist and Scientific principle is described in .

Table 2. Realist tenet, ontological/epistemological basis, and implications for realist evaluation.

Discussion

At the epistemological level, Realism seeks to understand the extent to which scientific theories access and describe the world as it is. Following this general raison d’être of Realism, its variants have some common basic tenets. Based on our exploration of the principles guiding scientific realism and critical realism, we find that they are underpinned by the notions of ontological depth and mechanism-based theorizing (Mukumbang, Kabongo, and Eastwood Citation2021). As such, they share identical tenets relating to the existence of a mind-independent reality, the unseen, upward and downward generative causation, stratified reality, emergence, the embrace of multiple methodologies, and the importance of theory in science (Brekke et al. Citation2019). With realist evaluation being supposedly informed by scientific realism (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997b), it stands to logical understanding that it would also be considered that Critical realist principles also underpin realist evaluation. Nevertheless, the different forms of Realism provide deeper explication and focus on different epistemological and ontological stances underpinning Realist evaluation.

Many authors who have explored the relationship between scientific realism and critical realism contend that they are closely related (Chernoff Citation2007). Whether one agrees that scientific realism and critical realism are closely related, many authors recognize their contributions to realist evaluation. For instance, Jagosh (Citation2020) illustrated that Bhaskar’s conceptualization informs the notion of ontological depth adopted in realist evaluation through the three ontological levels of reality for research activities, the Real, Actual, and Empirical, and the need for repeated scientific research efforts to capture the elusive generative mechanisms to approximate actual mechanisms. (Currie, Chiarella, and Buckley Citation2015) also suggested that the notion of ‘generative mechanism’, a fundamental tenet of realist evaluation, also emanates from Bhaskar’s explication of causality.

Our illustrations in and show that the Critical realist tenets and their implications for realist evaluation lend them to contribute to retroductive theorizing predominantly. At the same time, scientific realism focuses on the nature and role of the developing theory. The tenets of critical realism encourage retroductive theorizing, which requires empirical engagement and corroboration to conceptualize and validate generative mechanisms and theories. The Critical realist tenets, especially those related to generative causation, open systems, agent-agent – agent-structure relations, and emergence, underpin the different research approaches, methods, sources of data, and analytic inferential thinking. The transitive nature of reality offers insights into the nature of mechanisms and structures.

Scientific realism, contrariwise, predominantly focuses on describing the nature of the realist theories and their role in ‘accurately’ describing reality. In contrast, the intransitive nature illuminates the nature of the developing or emerging theory (no final truth, and theories can change as time evolves). provides important considerations while conducting a realist evaluation to ensure that the developing generative theory substantially describes how and why the programme works, for whom and under what conditions. This way, the realist evaluator should consider using multiple theoretical perspectives, theoretical saturation, judgmental rationality, and retrodiction. Therefore, scientific realism’s semantic notion focuses more on the objective nature of the programme theories elicited during the evaluation exercise. These theories are consequently examined at three levels: (i) an ontological sense of objectivity relating to the mind-independence of the natural world; (ii) a semantic form of objectivity relating to the nature of truth; and (iii) an epistemic notion of objectivity relating to methodological practices and justification underpinning their adoption.

Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) laid the foundations for realist evaluation with the focus, among other things, on explaining ‘how and why for whom and under what conditions programmes and policies work’ as a contribution to the varied approaches and methods used in evaluation sciences. They suggested that programmes work or not (outcomes) if they introduce ideas, constraints, and opportunities (mechanisms) to relevant actors in the appropriate relational, social and cultural conditions (contexts). Therefore, mechanisms acting in contexts is the axiomatic base upon which all realist explanation builds. Consequently, Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997a) conceptualized context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configuration to express causal explanations in realist evaluation inquiries. While the CMO configuration, for obvious reasons, is the most adopted in realist evaluation, CMO configurations have been criticized as limited in their explanatory potential. It has been suggested that the ‘mechanism’ represented in the CMO configurations as a combination of reasoning and resources implies that the mechanisms can be components of structure and agency. Consequently, determining the actual source of the mechanism becomes challenging and can erroneously be attributed entirely to the impact of the intervention (Hinds and Dickson Citation2021). As such, other explanatory factors have been added in other realist evaluation inquiries; it is recommended that any configuration type obtained from the addition of these factors must adhere to the rule of generative causation (De Weger et al. Citation2020).

Following the critical realist generative view of causality, Porter (Citation2015a) suggested that the realist evaluation configuration should include structural and agent mechanisms. (Mukumbang et al. Citation2017, Citation2018) support this suggestion stating that interventions cannot work unless taken up by the relevant actors, thus recommending the addition of ‘intervention’ and ‘actors’ to the original CMO configuration. To this end, Porter (Citation2015a) proposes ‘to identify the mechanisms embedded in an intervention and its social context, and those designed to uncover the experiences, interpretations, and responses of the actors involved’ (244). Brönnimann (Citation2021) also supports capturing the social mechanisms and actors’ perspectives embedded in the intervention. To this end, Mukumbang et al. (Citation2017, Citation2018) proposed the intervention-context-actor-mechanism-outcome (ICAMO) configuration as a robust heuristic tool for exploring realist programme theories. Porter (Citation2015a) proposed a more comprehensive formula for unpacking realist explanatory programme theories: Contextual Mechanisms + Programme Mechanisms + Agency = Outcome (CM + PM + A = O). His formula proposes that the evaluative process should consider the generation and testing of hypotheses about the mechanisms embedded in the extant social context (CM), the programme mechanisms (PM), and an examination of how agents interpret and respond to these mechanisms (A) leading to the observed outcome (O). In adopting this approach, Bhaskar warns that:

It will not generally be possible to specify how a mechanism operates independently of its context. Hence, we must not only relate mechanisms to explanatory or grounding structures, as in the theoretical natural sciences, but also to context or field of operation. This means that in the social field, in principle, we always need to think of a context-mechanism couple, C + M, and thus of the trio of context, mechanism, outcome (CMO), or more fully, the quartet composed of context, mechanism, structure, and outcome (CMSO). (Bhaskar Citation2016, 80)

Conclusion

The ontological foundation of realist evaluation remains confusing among many novice realist researchers. This paper aims to clarify the nature of the principles underpinning realist evaluation to improve the application of realist evaluation in practice. In this paper, we illustrated that both scientific realism and critical realism make different but substantial contributions regarding realist evaluation’s ontological and epistemological foundations. We illustrated that while Critical Realism and Scientific Realism are informed by Realism and share common tenets, they provide slightly different but complementary tenets that underpin realist evaluation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2023.2232661).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ferdinand C. Mukumbang

Ferdinand C. Mukumbang is an Assistant Professor of Implementation sciences at the Global Health of Woman Adolescents and Children (Global WACh) research unit, Department of Global. He has a broad background in Public Health, with specific training and expertise in health systems and policy research and particular research methodology expertise in realist-informed research methodologies.

Denise E. De Souza

Denise E. De Souza is a postdoctoral fellow at Torrens University Australia. Her interests include conducting reviews and publishing on policy and program evaluations in Education and Public Health.

John G. Eastwood

John G. Eastwood is Clinical Director – Localities, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, New Zealand; Acting Chief Medical Officer and Public Health Physician, Southern District Health Board, New Zealand; Executive Clinical Advisor Clinical Services Integration and Population Health, Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia; Director Early Years Research Group, Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Research, UNSW, Australia; Director National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence for Integrated Health and Social Care; Co-Chair Sydney Institute for Women, Children and their Families; and Director Healthy Homes and Neighborhoods Integrated Care Initiative, Sydney, Australia. He is also an Adjunct Professor, School of Population Health, UNSW, Sydney, Australia; Clinical Professor University of Sydney, Australia; Honorary Clinical Professor Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, and Visiting Academic Sydney Children's Hospital Network.

Notes

1 We have used intervention in this manuscript to represent policies, programme, and interventions, which are designed to change the behaviour of a targeted group of people.

2 The term ‘scientific realism’ in small caps represents those within realist evaluation who tend to view their evaluative work as being rather exclusively associated with Bhaskar's and other realist work done in the sciences and ‘critical realism’ to those associating their work more with Bhaskar's and Archer's work in the human sciences, respectively.

3 For purposes of clarification, we use the term ‘Critical Realism’ here to refer to the philosophical movement that has come to be associated with the works of Roy Bhaskar.

References

- Allana, S., and A. Clark. 2018. “Applying Meta-Theory to Qualitative and Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion of Critical Realism and Heart Failure Disease Management Interventions Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1177/1609406918790042.

- Allzén, S. 2021. “Scientific Realism and Empirical Confirmation: A Puzzle.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 90 (February): 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2021.10.008.

- Alvesson, M. 2002. Postmodernism and Social Research. Open University Press. https://www.socresonline.org.uk/8/2/alvesson.html.

- Archer, M. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511557675.

- Archer, M. S. 2020. “The Morphogenetic Approach; Critical Realism’s Explanatory Framework Approach.” Virtues and Economics 5: 137–150. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-26114-6_9.

- Bhaskar, R. 1975. “Forms of Realism.” Philosophica 15 (1): 99–127. doi:10.21825/philosophica.82713.

- Bhaskar, R. 1989. Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. London: Verso.

- Bhaskar, R. 1998. Critical Realism and Dialectic. Edited by M. Archer. Routledge. https://philpapers.org/rec/BHACRA-2.

- Bhaskar, R. 2009. Scientific Realism and Human Emancipation. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203879849.

- Bhaskar, R. 2016. “Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism.” In Journal of Critical Realism, edited by Mervyn Hartwig, vol. 4, 244 p. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315542942.

- Bhaskar, R., and T. Lawson. 2013. “Introduction: Basic Texts and Developments.” In Critical Realism: Essential Readings, edited by Margaret Archer, Roy Bhaskar, Andrew Collier, Tony Lawson, and Alan Norrie, 3–15. London: Routledge.

- Brekke, J., J. Anastas, J. Floersch, and J. Longhofer. 2019. “The Realist Frame.” Shaping a Science of Social Work, 22–40. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190880668.003.0002.

- Brönnimann, A. 2021. “How to Phrase Critical Realist Interview Questions in Applied Social Science Research.” Journal of Critical Realism 21: 1–24. doi:10.1080/14767430.2021.1966719.

- Chernoff, F. 2007. “Critical Realism, Scientific Realism and International Relations Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 35 (2): 399–407. doi:10.1177/03058298070350021701.

- Costa, D. M., and R. Magalhães. 2019. “Evaluation of Health Programs, Strategies, and Actions: A Dialogue with Critical Realism.” Saúde em Debate 43 (spe7): 189–203. doi:10.1590/0103-11042019s715.

- Currie, J., M. Chiarella, and T. Buckley. 2015. “Preparing a Realist Evaluation to Investigate the Impact of Privately Practising Nurse Practitioners on Patient Access to Care in Australia.” International Journal of Nursing 2 (2): 1–10. doi:10.15640/ijn.v2n2a1.

- Danermark, B., M. Ekström, and J. C. Karlsson. 2019. “Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences.” In Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9781351017831.

- de Souza, D. E. 2014. “Culture, Context and Society – The Underexplored Potential of Critical Realism as a Philosophical Framework for Theory and Practice.” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 17 (2): 141–151. doi:10.1111/ajsp.12052.

- de Souza, D. E. 2022. “A Critical Realist Approach to Systems Thinking in Evaluation.” Evaluation 28 (1): 72–90. doi:10.1177/13563890211064639.

- De Weger, E., N. J. E. Van Vooren, G. Wong, S. Dalkin, B. Marchal, H. W. Drewes, and C. A. Baan. 2020. “What’s in a Realist Configuration? Deciding Which Causal Configurations to Use, How, and Why.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940692093857. doi:10.1177/1609406920938577.

- Downward, P., and A. Mearman. 2007. “Retroduction as Mixed-Methods Triangulation in Economic Research: Reorienting Economics Into Social Science.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 31 (1): 77–99. doi:10.1093/cje/bel009.

- Elder-Vass, D. 2008. “Searching for Realism, Structure and Agency in Actor Network Theory.” The British Journal of Sociology 59 (3): 455–473. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00203.x.

- Elder-Vass, D. 2010. “The Causal Power of Social Structures: Emergence, Structures and Agency.” In Structure (First). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511761720.

- Elder-Vass, D. (2015). Disassembling Actor-network Theory. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 45 (1): 100–121. doi:10.1177/0048393114525858.

- Evangelopoulos, G. 2013. “Scientific Realism in the Philosophy of Science and International Relations.” Phd diss., London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Fleetwood, S. 2017. “The Critical Realist Conception of Open and Closed Systems.” Journal of Economic Methodology 24 (1): 41–68. doi:10.1080/1350178X.2016.1218532.

- Fletcher, A. J. 2017. “Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology Meets Method.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401.

- Gage, N. L. 2016. “The Paradigm Wars and Their Aftermath A “Historical” Sketch of Research on Teaching Since 1989.” Educational Researcher 18 (7): 4–10. doi:10.3102/0013189X018007004.

- Greenhalgh, J., and A. Manzano. 2021. “Understanding ‘Context’ in Realist Evaluation and Synthesis.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 25 (5): 583–595. doi:10.1080/13645579.2021.1918484.

- Greenhalgh, T., G. Wong, J. Jagosh, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, G. Westhorp, and R. Pawson. 2015. “Protocol—the RAMESES II study: Developing Guidance and Reporting Standards for Realist Evaluation: Figure 1.” BMJ Open 5 (8): e008567. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008567.

- Harre, R., and P. F. Secord. 1972. The Explanation of Social Behaviour. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Harré, R. 2006. How to Change Reality: Story v. Structure – A Debate Between Rom Harre and Roy Bhaskar. Edited by G. Lopez and J. Potter. The Athlone Press. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=556_556459-ypjayidpkt&title=COVID-19-and-key-workers-What-role-do-migrants-play-in-your-region.

- Hinds, K., and K. Dickson. 2021. “Realist Synthesis: A Critique and an Alternative.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/14767430.2020.1860425.

- Hesse, M., 1974. The Structure of Scientific Inference. University of California Press.

- Jagosh, J. 2020. “Retroductive Theorizing in Pawson and Tilley's Applied Scientific Realism.” Journal of Critical Realism 19 (2): 121–130. doi:10.1080/14767430.2020.1723301.

- Keat, R. 1971. “Positivism, Naturalism, and Anti-Naturalism in the Social Sciences.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 1 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1971.tb00163.x.

- Khalidi, M. A. 2016. “Mind-Dependent Kinds.” Journal of Social Ontology 2 (2): 223–246. doi:10.1515/jso-2015-0045.

- Lakatos, I. 1970. Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. In Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, edited by I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lawson, T. 2001. “Economics and Explanation.” Revue Internationale de Philosophie 217 (3): 371–393. doi:10.3917/rip.217.0371

- Marchal, B., S. van Belle, J. van Olmen, T. Hoerée, and G. Kegels. 2012. “Is Realist Evaluation Keeping its Promise? A Review of Published Empirical Studies in the Field of Health Systems Research.” Evaluation 18 (2): 192–212. doi:10.1177/1356389012442444.

- MESH. 2017. Article: Critical Realist Evaluation, October 13. https://mesh.tghn.org/articles/critical-realist-evaluation/.

- Meyer, S. B., and B. Lunnay. 2013. “The Application of Abductive and Retroductive Inference for the Design and Analysis of Theory-Driven Sociological Research.” Sociological Research Online 18: 86. doi:10.5153/sro.2819.

- Mukumbang, F. C. 2021. “Retroductive Theorizing: A Contribution of Critical Realism to Mixed Methods Research.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 17 (0): 93–114. doi:10.1177/15586898211049847.

- Mukumbang, F. C., E. M. Kabongo, and J. G. Eastwood. 2021. “Examining the Application of Retroductive Theorizing in Realist-Informed Studies.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–14. doi:10.1177/16094069211053516.

- Mukumbang, F. C., B. Marchal, S. Van Belle, and B. Van Wyk. 2018. “Unearthing How, Why, for Whom and Under What Health System Conditions the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club Intervention in South Africa Works: A Realist Theory Refining Approach.” BMC Health Services Research 18. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3150-6.

- Mukumbang, F. C., S. Van Belle, B. Marchal, and B. Van Wyk. 2016. “Realist Evaluation of the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club Programme in Selected Primary Healthcare Facilities in the Metropolitan Area of Western Cape Province, South Africa: A Study Protocol.” BMJ Open 6 (4): e009977. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009977.

- Mukumbang, F. C., S. Van Belle, B. Marchal, and B. Van Wyk. 2017. “An Exploration of Group-Based HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care Models in Sub-Saharan Africa Using a Realist Evaluation (Intervention-Context-Actor-Mechanism-Outcome) Heuristic Tool: A Systematic Review.” Implementation Science 12: 1. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0638-0.

- Oakley, A. 1999. “Paradigm Wars: Some Thoughts on a Personal and Public Trajectory.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2 (3): 247–254. doi:10.1080/136455799295041.

- Parker, I. 1998a. Social Constructionism: Discourse and Realism. SAGE. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-06306-000.

- Parker, Ian. 1998b. Social Constructionism, Discourse, and Realism. SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781446217412.

- Pawson, R. 2006. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. University of Leeds, UK.

- Pawson, R. 2013. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781473913820.

- Pawson, R., T. Greenhalgh, G. Harvey, and K. Walshe. 2005. “Realist Review - A New Method of Systematic Review Designed for Complex Policy Interventions.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 (1_suppl): 21–34. doi:10.1258/1355819054308530.

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 1997a. “An Introduction to Scientific Realist Evaluation.” In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook, 405–418. doi:10.4135/9781483348896.N29.

- Pawson, R., and Nick Tilley. 1997b. Realistic Evaluation. Sage. doi:10.1177/135638909800400213.

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 2004. Realist Evaluation. http://www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf.

- Porter, S. 2015a. “Realist Evaluation: An Immanent Critique.” Nursing Philosophy 16 (4): 239–251. doi:10.1111/nup.12100.

- Porter, S. 2015b. “The Uncritical Realism of Realist Evaluation.” Evaluation 21 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1177/1356389014566134.

- Porter, S. 2015c. “Realist Evaluation: An Immanent Critique.” Nursing Philosophy 16 (4): 239–251. doi:10.1111/nup.12100.

- Porter, S. 2017. “Evaluating Realist Evaluation: A Response to Pawson's Reply.” Nursing Philosophy 18 (2): e12155. doi:10.1111/nup.12155.

- Porter, S., and P. O’Halloran. 2012. “The Use and Limitation of Realistic Evaluation as a Tool for Evidence-Based Practice: A Critical Realist Perspective.” Nursing Inquiry 19 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00551.x.

- Psillos, S. 2000. “The Present State of the Scientific Realism Debate.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 51 (SUPPL.): 705–728. doi:10.1093/bjps/51.4.705.

- Renmans, D., N. Sarkar, S. Van Belle, C. Affun-Adegbulu, B. Marchal, and F. C. Mukumbang. 2022. “Realist Evaluation in Times of Decolonising Global Health.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 37: 37–44. doi:10.1002/hpm.3530.

- Rossi, P. H., M. W. Lipsey, and G. T. Henry. 2018. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. 8th ed. London: Thousand Oaks.

- Sankey, H. 2001. “Scientific Realism: An Elaboration and a Defence.” Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory 98: 35–54. doi:10.1515/krt-2021-0002.

- Sankey, H. 2021. “Realism and the Epistemic Objectivity of Science.” KRITERION – Journal of Philosophy 35 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1515/krt-2021-0002.

- Sayer, A. 2000. Realism and Social Science. SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781446218730.

- Smeets, R. G. M., D. F. L. Hertroijs, F. C. Mukumbang, M. E. A. L. Kroese, D. Ruwaard, and A. M. J. Elissen. 2021. “First Things First: How to Elicit the Initial Program Theory for a Realist Evaluation of Complex Integrated Care Programs.” The Milbank Quarterly 100 (0): 151–189. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12543.

- Sorrell, S. 2018. “Explaining Sociotechnical Transitions: A Critical Realist Perspective.” Research Policy 47 (7): 1267–1282. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.04.008.

- Tennant, E., E. Miller, K. Costantino, D. De Souza, H. Coupland, P. Fotheringham, and J. Eastwood. 2020. “A Critical Realist Evaluation of an Integrated Care Project for Vulnerable Families in Sydney, Australia.” BMC Health Services Research 20 (1). doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05818-x.

- Wilson, V., and B. McCormack. 2006. “Critical Realism as Emancipatory Action: The Case for Realistic Evaluation in Practice Development.” Nursing Philosophy 7 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00248.x.