ABSTRACT

In the discourse of value-laden tourism research, knowledge about the mechanisms that manifest civilized tourism is limited. This paper uses empirical research as a basis from which to explore the generative powers of civilized tourism at the structural level of society. It identifies the structural properties of civilized tourism and five situational logics. Civilized tourism is related to civility, China’s Dream, and social etiquette. These other ideas provide a condition for civilized tourism to exist. All the situational logics function to co-determine the nature of civilized tourism in the cultural system. Based on the findings, it concludes that the call for civilized tourism in China provides a condition for the formation of ethicality in tourism, which is not reducible to tourism stakeholders. The formation of ethicality is conditioned by the product of past socio-cultural interactions whilst engineered by the protective and corrective situational logics of the idealizations taking place in the present time.

Introduction

The emerging discourse of hopeful tourism (Hunter Citation1997; Lee et al. Citation2017; Pritchard, Morgan, and Ateljevic Citation2011; Sampaio, Thomas, and Font Citation2012; Schultz et al. Citation2005; Tolkach, Pratt, and Zeng Citation2017) has demonstrated an increasing emphasis of underlying ethics and moral values in tourism studies, e.g. Fennell (Citation2018). A growing research interest in civilized tourismFootnote1 (Dai and Qin Citation2001; Hu Citation2008; Lin Citation2012; Luo Citation2016; Qu et al. Citation2021; Tian Citation1999; Wang and Kuang Citation2011; Wang, He, and Bi Citation2017; Xia Citation2003) contributes to this discourse. All the efforts aim to understand the value-ladened nature of tourism activities and inherent issues so that solutions may be sought to effectively develop responsible, sustainable and equally accessible tourism (Malloy and Fennell Citation1998; WTO Citationn.d.) or socially accepted tourist behaviours and practices in China. Li (Citation2022), however, has pointed out how little we know about enhancing morally guided tourism effectively so that socially responsible tourism (WTO Citationn.d.) can be realized globally. The present study contributes to the discourse of value-laden tourism research by going deeper to find underlying mechanisms of civilized tourism in China. It investigates the properties of civilized tourism at the structural level. It therefore asks what these structures are; and how they may have contributed to the emerging moral/ethical elaboration of civilized tourism in China. It is hoped that by knowing the mechanisms that cause the manifestation of civilized tourism, solutions can then be developed to enhance morally guided tourism effectively.

The argumentation of the paper will be developed in this order: (1) The goal of scientific work in social sciences is to find the mechanisms derived from the properties of structure and that of human agency so as to explain social reality (see section ‘Why should we search for mechanisms?’). (2) In the discourse of value-laden tourism research, knowledge about the mechanisms that manifest morally guided tourism (including ethical tourism and civilized tourism) is limited and thus there is a need to pursue a project that generates new knowledge to fill in this knowledge gap; this paper contributes to the project by focusing on the cultural mechanisms (i.e. section ‘What do we know about the mechanisms in civilized tourism?’). (3) More specifically, this paper focuses on the generative powers of China’s civilized tourism at the structure level. Drawing from Archer’s (Citation1995, Citation2008) seminal discussions on the working of cultural mechanisms in shaping social reality, how the cultural mechanisms of civilized tourism can be (theoretically) identified is outlined in section ‘How do cultural mechanisms bring about social reality? A realist theoretical perspective’. (4) How the mechanisms can be identified, methodologically, are explained in section ‘Philosophical underpinnings’. The research design section explains the processes of the research while its following two sections present the argumentation of the properties of civilized tourism and their situational logics. (5) Lessons learned from this research, the implications of the findings, and future research directions are then articulated in the conclusion.

Why should we search for mechanisms?

Scientific activities are to find the mechanisms that cause what we see and/or experience (Bhaskar Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2020). If we only focus on what we see and/or experience then we would limit ourselves to an incomprehensive explanation about social reality (Bhaskar Citation2020). A mechanism is a causal law – ‘a way of acting of a thing’ (Bhaskar Citation2008, 51). It is derived from the properties of structure and that of human agency. The properties of an emerging entity are defined by its internal structure and its structural relationship with other entities (Porpora Citation2021). They have autonomous causal powers and liabilities. For instance, positional rights and obligations are the properties of social positions (Lawson Citation2019). Tourists are expected to take responsibilities for, for example, obeying local laws and protecting the natural wildlife (Swarbrooke Citation1999). One’s self-regulatory efficacy is a property of humans that shapes the person’s moral engagement (Bandura et al. Citation2001). The properties are also liable to change, e.g. tourists’ self-efficacy beliefs can be enhanced by persuasive communication (Shahzalal and Font Citation2018).

What do we know about the mechanisms in civilized tourism?

Discussions on civilized tourism in China surfaced in the 1980s (Tian Citation1999). Overall, research on China’s civilized tourism in English written academic outlets seems to be very limited. This is reflected in Huang, ven der Veen, and Zhang’s (Citation2014) and Xu, Ding, and Packer’s (Citation2008) reviews of tourism research in China wherein civilized tourism is not mentioned at all. A recent publication by Li, Hazra, and Wang (Citation2023) makes a step forward to fill in this knowledge gap. On the other hand, in Chinese written literature, academic discussions and empirical studies on civilized tourism are more apparent.

Some examples of relevant conceptual papers are Pei (Citation2016) and Tuo and Li (Citation2018). Pei (Citation2016) has discussed ways through which civilized tourism practices can be enhanced whereby legal and social systems are to be further developed so that practices displayed by tourism participants (i.e. individuals and organizations) can be monitored and regulated more efficiently, in addition to encouraging individuals to be self-disciplined with their behaviours. Pei’s remarks do not bring in any insights or novelty because social sanction (e.g. regulating behaviours through laws) and self-sanction, which are two main self-regulatory mechanisms in moral reasoning of individuals, have been extensively researched on in social psychology (Bandura Citation2001; Bandura et al. Citation2001). Yet, no reference is made to this body of knowledge in Pei’s writing.

This seems to reflect a general tendency of the absence of rigorous theoretical engagement in scholarly work within the academic community in China. For example, Hu (Citation2008) and Lin (Citation2012) argue for ‘moral weakening’ as a notion to define uncivilized tourist behaviour; yet the theoretical ground for the concept is omitted. Bi, Li, and Zhang (Citation2019) discuss the influences of ‘motivation, opportunity and ability on [sic] uncivilized tourism behavior’ (1203) on uncivilized tourism behaviours, again, without an explicit theoretical ground. Or, this may simply echo the issue that Tuo and Li (Citation2018) have highlighted that in research on (un)civilized tourism behaviours ‘a mature theory system has not yet been formed’ (102). They call for a more diversified approach involving all stakeholders in the system of civilized tourism. Yet, this will need a robust social theory(-ies) that can explain the interactions among the collectivities of the social actors.

In terms of areas of focus, empirical research on civilized tourism tends to focus on uncivilized behaviours displayed by Chinese outbound tourists. Our observation seems to be consistent with the position identified by Tuo and Li (Citation2018) and Tse (Citation2011, Citation2015). For example, Wang, He, and Bi (Citation2017) have reported uncivilized behaviours by Chinese outbound tourists in Thailand, Japan, and Korea in the interval of 2014 and 2016. Tran (Citation2020) has investigated Chinese tourists’ uncivilized behaviours in Vietnam. The focus has been on tourists’ behaviours, thus unsurprisingly Tse (Citation2015) calls for research on the ethical aspects of Chinese outbound tourism.

Less popular research topics are seen in a handful of studies. For example, Loi and Pearce (Citation2012) investigate what behaviours are perceived undesirable in the perspectives of host-tourist relations; however, realists would argue that social reality cannot be reduced to our perceptions only. Huang, Zhang, and Luo (Citation2022) discuss the correlation between tourism development and the development of ecological civilization in the ethnic areas in the west of China. They do so at the expense of removing human agency out of the equation of social change. Li and Cheng (Citation2016) propose a contextualized approach to civilized tourist behaviour from a socio-psychology lens but they have not provided a detailed account about the mechanisms involved. A few studies have made some attempts to discover mechanisms, for example, Yi (Citation2018) on emotion in moral reasoning. Zhang et al. (Citation2020) have also discussed tourists’ emotions attached to uncivilized behaviours displayed by other tourists. More recently, Li, Hazra, and Wang (Citation2023) report that positional powers and the present social movement of civilized tourism development in China have co-created a condition that triggers psychological and social causes which are engineered by agents’ capabilities of recognizing their ultimate concerns, reflexive and evaluative reasoning, forging of identity, moral engagement, and learning.

Abundant studies examine the influential factors of (un)civilized tourism behaviours displayed by Chinese tourists with an attempt to predict future behaviour or the intention of it (Gao and He Citation2020; Huang Citation2019; Li Citation2018; Li and Li Citation2020; Lu, Yin, and Tao Citation2019; Tran Citation2020; Wang, He, and Bi Citation2017; Xu and Huang Citation2019; Zhang and Qiu Citation2020; Zhou, Xu, and Liu Citation2021). These predictive studies apply the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen Citation1991) and, to a lesser degree, value-belief-norm theory (Schwartz Citation1992) and calculate correlations among the variables, upon which they claim the discovery of ‘mechanism’.

Our observation of civilized tourism research seems to be in line with Luo’s (Citation2016) three phases [or more accurately categories of research approach] – individualistic critique [e.g. studies on uncivilized tourists’ behaviours], collectivist reasoning [e.g. Pei (Citation2016)], and progressive social movement (e.g. Luo Citation2016; Zhang and Qiu Citation2020). For example, Lou (Citation2016), basically, suggests that scholarly work and political initiatives vis-à-vis civilized tourism have progressed through these three phases across time. We regard Luo’s view rather conflated – arguably, academic research and political conduct may influence each other but they are nevertheless two different aspects of social reality with their own respective, unique reasons for their existence. Further, the suggested correlation between time and the approach of work being individualistic, collectivist, or progressive is questionable. Based on our reading of literature, these three categories do not appear to correlate with the temporal dimension.

In essence, knowledge about the mechanisms that shape the emergence of civilized tourism in China is basically absent, with the exception of Li, Hazra, and Wang (Citation2023). The majority of the efforts aim to explain civilized tourism, pondering solutions to enhance its practice, but they struggle to find appropriate tools to achieve the aim. It seems to us that the challenge lies in (1) the topic has been overlooked, (2) the methodological programmes adopted are problematic in finding the answers, and (3) the absence of a robust philosophical and theoretical foundation for civilized tourism research. Point (1) refers to: ontologically, the majority of aforesaid empirical studies tend to stay at the empirical level and not be able to make the leap from the empirical domain to the real domain. This tendency is also commented on in Li’s (Citation2022) critique of ethical tourism research.

With regard to point (2), Li (Citation2022) maintains that even in ethical studies that have attempted to understand individuals’ moral decision-making, the actual processes of moral reasoning are often treated as a ‘black box’ (Bunge Citation2004) which is, indeed, witnessed in, for example, Wang, He, and Bi (Citation2017) who use network text analysis to support a regularity of pattern wherein immoral uncivilized behaviours displayed by Chinese outbound tourists occur the most in Thailand and Korea whilst the illegal uncivilized behaviours and alienated uncivilized behaviours are the most in Japan. Qu et al. (Citation2021) employ structural equation modelling as their base for the claim that civilized tourism behavioural intention is determined by national image, national identity, patriotism, and psychological ownership.

The ‘black box’ reasoning is a key feature of Popper–Hempel explanatory model that uses deductive inference, wherein causal conclusions are drawn based on observations of how something is repeatedly followed by something else i.e. treating event occurrences regularity as causality (Bunge Citation2004). This explanatory model has been heavily criticized in research philosophy (c.f. Danermark, Ekström, and Karlsson (Citation2019) on theory in the methodology of social science and Hartwig (Citation2007) on causal mechanism). It is so because: (1) the model reduces reality to the empirical domain and wrongly treats causality as regular connections between observable events; (2) what quantitative analysis does is to suggest a correlation between two concepts or events with a certain level of statistical confidence, but the correlation itself does not provide a meaningful explanation of the causal process(es) in that regular pattern (Archer Citation2015).

Further, referring back to the predictive studies, can we really predict tourists’ behaviours? This is basically concerned with our ability to explain society (and things in it), its past, present, and future. As far as point (3) is concerned, tourism scholars, like other researchers of social science, face the difficulty in dealing with structure and agency in their efforts to provide an explanation of social lives. The traditions of theorizing society are Individualism and Collectivism. In the Individualism tradition, structure becomes the inet and dependent element of social reality. In the Collectivism tradition, in contrast, agency is neglected. Individualism is seen in, for example, Dai and Qin (Citation2001), Hu (Citation2008), Lin (Citation2012), Xia (Citation2003), and Wang and Kuang (Citation2011) while Collectivism is witnessed in Xia and Liu (Citation2016) who discuss the relationship between tourism and civilization being derived from modernity and post-modernity while taking agency out of the equation.

It has been extensively discussed that ‘neither Individualism nor Collectivism can furnish the basis for adequate social theorizing’ (Archer Citation1995, 33), because they have committed to ontological conflations (Archer Citation1995; Bhaskar Citation2008). Realists argue that social reality emerges from structure (including social structure and cultural structure), agency (i.e. a human’s thinking, talking, and acting), and the interplay between them, and that structure governs the reproduction and transformation of social activities, yet its existence requires human actions (Archer Citation1995; Citation2000; Citation2008; Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012).

Because the social world is more than what we perceive, see, and experience, any attempt to explain the emergence of civilized tourism will need to go deeper than the empirical to discover the mechanisms that might have occurred to have brought about the effects that are manifested. This can only be achieved with the assistance of social theory(-ies) that has a robust ontological base; one would end up with an unsophisticated project otherwise. One such theory is Archer’s (Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2008) critical realist social theory wherein she discusses morphostasis (or reproduction) and morphogenesis (transformation) of social change in her Structure-Agency-Culture trilogy. Her morphogenesis approach is widely adopted in different fields of study (e.g. Mutch Citation2010; Njihia and Merali Citation2013). Such an example in tourism studies is Li (Citation2022) whilst realist research papers in the tourism domain are very limited (e.g. Botterill et al. Citation2013; Lau Citation2009). The present paper builds upon Archer’s theory to address the knowledge gap.

How do cultural mechanisms bring about social reality? A realist theoretical perspective

This section aims to address the question of how the cultural mechanisms of civilized tourism could be discovered theoretically. To achieve this, effort is needed to, first of all, clean the minefield of what culture is, which is followed by a discussion of literature on how cultural mechanisms function to bring about social reality in the critical realist perspective. The focus will be given to how the mechanisms could be identified from the theoretical perspective. The objectives of this research will be developed upon these discussions at the end of the section.

What is culture? A realist perspective

This section argues that culture consists of subjective and objective moments (Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012), taking a position that is away from the traditional conceptualization of culture. ‘ … [I]t is generally agreed [the authors’ emphasis] that [in the debates on tourism culture] the cultural aspects of the “guests” (their motivation and behaviour); the cultural aspects of the “host society or nature”; and the host–guest relationship should all become the subject of research’ (Xu, Ding, and Packer Citation2008, 481). In principle, the authors of the present paper can resonate with (1) the ‘guests’ aspect, (2) the ‘host society or nature’ aspect, and (3) the host–guest relationship. (1) and (3) are concerned with agency – (1) being human agency at the individual level and (3) being social interactions between individual actors. Aspect (2) is, however, less clear – Firstly, the reference to ‘nature’ is inapprehensible. Secondly, in terms of the reference to ‘host society’, does it mean ideas/beliefs/values shared among the members of the host society through the mode of acting in the mundane routines? Or, shared ideas expressed in the shared symbolic system of communication of the host society? Or, both? The words ‘generally agreed’ seem to indicate the writers’ position that is inclined to the sharedness of ideas within a given society or community, which seems to be the one taken by researchers of tourism cultural studies in China (Yu, 1995; cited in Xu, Ding, and Packer Citation2008).

Culture has been traditionally regarded as something that is shared and coherent, which is, however, challenged by scholars, such as Archer (Citation2008) and Maxwell (Citation1999). This tradition creates what Archer (Citation2008) calls ‘Myth of Cultural Integration’ (2). This traditional conceptualization of culture has failed to explain cultural divisions and cultural contradictions because it ‘wrongly and unhelpfully elides the “meanings” with their being “shared”’ (Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012, 95). Realists accept that social life is concept dependent but not exhausted by its conceptuality; social life has a material dimension too (Bhaskar Citation2020). Culture features subjective and objective moments (Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012). The subjective moment refers to the meanings of the item as perceived by social actors whereas the objective features are called cultural system or intelligibilia (Archer Citation2008), including objective items, such as texts, theories, and ideologies, and the logical relations between them (Archer Citation2008). The cultural system is the pool of knowledge from which items are drawn to resolve apparent inconsistencies and/or to deal with the unknown.

Analytic dualism: unpacking culture

This section discusses how the working of culture can be analysed through analytic dualism (Archer Citation2008), which basically involves a separation of structure and agency so that the interplays between them can be examined. ‘Meanings’ that are perceived by social actors take place at the socio-cultural level i.e. the subjective moment of culture at the human agency level. ‘Sayings’ are what have been codified at the cultural system level (or the structure level). They are the objective moment of culture. ‘Meanings’ and ‘sayings’ need to be analytically separated so that the difficulties resulting from the contextual-dependence of cultural items can be overcome (Archer Citation2008, Citation2012).

Archer’s analytic dualism provides a useful and practical tool to overcome the difficulties in dealing with cultural inconsistency. It entails a rejection to Bloor’s (Citation1981) and Barnes (Citation1981) treatment of inconsistency as a matter of local convention, which is often seen in ethical tourism studies. For example, Buzar (Citation2015) believes that Global Conduct of Ethics for Tourism (World Tourism Organization Citationn.d.) being a single global ethos for tourism is ‘a serious point of dispute and controversy in descriptive ethics’ (55) because it fails to reconcile the universal propositions and norms it advocates with the cultural relativist dimension of ethics.

However, the codes of ethics are ‘sayings’ about how practice should be conducted based on agreed moral values and rules; they are the objective moments of culture residing at the structure level. On the other hand, the individual perceptions and beliefs about moral values and rules are ‘meanings’ – the subjective moments of culture residing at the agency level. ‘Sayings’ and ‘meanings’ are not directly connected; they need to be analysed separately. As Archer (Citation2008) has rightly pointed out, without such a treatment the explanation about knowledge would have been marked out to the entire cultural domain.

How does culture shape social reality?

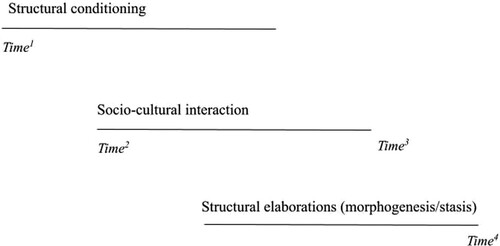

The reproduction and transformation of culture occur through a morphogenetic cycle of structural conditioning, interactions, and elaboration (Archer Citation2008) (). In short, Archer argues that an object has its inner structure, of which existence predates the present agents (i.e. Time1) and which necessarily possesses causal powers and liabilities. The object interacts with other objects which also have their respective powers and liabilities. The interactions of the objects enable and/or constrain the actions of agents (i.e. socio-cultural interactions from Time2 onwards) under specific conditions. The socio-cultural interactions either do not produce any change if the proper condition is not activated (i.e. morphostasis or reproduction) or produce different types of changes, subject to the activated conditions proper for them to occur (i.e. morphogenesis or transformation).

Figure 1. Archer’s morphogenetic/static cycle, adapted from Archer (Citation1995). Reproduced with permission of The Licensor through PLSclear.

But, how exactly does the culture bring about cultural reproduction and transformation? Prior to answering this question, the properties of culture need to be discussed. The relationships among cultural items are logical: inconsistency, consistency, or independence between them (Archer Citation2008; Lukes Citation1967). Thus, Archer (Citation2008) argues that (in)consistencies to other ideas are the properties of the cultural system and that these properties create two different situational logics: correcting the inconsistencies (i.e. corrective logic) and protecting the consistencies (i.e. protective logic). The workings of these logics are autonomous – independent of their identification by agents, but they enable and/or constrain agencies (i.e. structural conditioning).

Elder-Vass and Archer both agree on the objective and subjective features of culture, but they offer alternative accounts about how culture shapes social reality. Regarding Archer’s (Citation2008) intelligibilia as a part of norm circles, Elder-Vass argues that culture is a shared set of practices and understandings emerged from these norm circles whereby a group of people who are committed to endorsing and enforcing a particular norm exert normative influence on their members; but for Archer, the ‘sharing’ is always an aim on the part of one particular group and ‘never a definition’ (Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012, 109).

Archer (Citation2008) also argues that the sharing of ideas is contingent i.e. there are socio-cultural matters – the existence depends upon other people, and that the ideas and groups interplay dynamically. Socio-cultural variations can be explained by looking at how the social or sectional distribution of interests (things that matter to individuals and/or groups) and of power actually gel with the situational logics of the cultural system or its subsystem at any given time (Archer Citation2008). ‘Power’ is ‘a relational property … not some kind of generalized capability’ (Archer Citation2008, 340). It is exercised between two parties, the receiver(s) responds to the other party differently in accordance with their interests, subject to their capability of human agency and access to available resources.

From the realist perspective, there are three types of power strategy, namely the decision-making dimension, the non-decision-making dimension, and ideational or ideological naturalization in cultural manipulations (Archer Citation2008; Dowding Citation2006; Lukes Citation2005). These strategies are exercised at the socio-cultural level vis-à-vis cultural system’s situational logics -–social actors’ actions are directed by their use of power and their interests that are consistent, or conflict, with the situational logic they confront.

In a cultural context that is ripped apart by inconsistencies and thus needs repair, the power and interests of social actors involved can lead them to embark on correction or to exploit the systemic contradictions. In a cultural context that is driven by consistency, social actors’ power and interests can lead them to protect the consistency or to migrate to another cultural environment seeking opportunities to realize their promotive interests. Thus, socio-cultural variations exist in each context, subject to the degree of the corrective/protective manoeuver’s impingement upon the interests and capability of agency of the ‘receivers’ of the cultural manipulations (Archer Citation2008). These interactions account for cultural elaboration. Their enduring working is ultimately responsible for the germination of the seeds of systemic inconsistency and consistency.

Contextualization

What does culture in China entail? In a realist perspective, as a society develops, the cultural system at the present time is different from that at the last moment of time in the previous morphogenetic cycle because the knowledge has grown or impoverished in cultural regression (Archer Citation2008). Indeed, as a Confucian heritage country, Confucian values and moral rules form a significant part of China’s cultural system (Li and Rivers Citation2018) and influence tourists’ motivation (Shao and Perkins Citation2017). In contemporary China, some of the Confucian positions are no longer practised by people, such as sacrificing one’s son to show one’s loyalty to the sage, whilst some positions have been modified to fit the current societal needs, such as encouraging women to be educated and become key contributors to economies like the men do, instead of the expectation of undertaking only the caring role in the family. Further, given the country’s political position and emphasis on economic development, its cultural system unavoidably embraces propositions of social communism and capitalism, not to mention distinctive sets of cultural values and norms of its 56 ethnic groups and the Eurocentric propositions that are visible to the Chinese people.

Civilized tourism is one idea in China’s culture system. It is also a pattern of social practice at the agency level. The call for civilized tourism emerged from the flourishing of China’s outbound and domestic tourism development which have brought about reports of criticism of some tourist behaviours at destinations. To overcome the negative social impacts of tourism, the Civilization Office of the Central Communist Party Committee (hereafter CO) and the China National Tourism Administration announced the launch of the Guidance of Chinese Citizens’ Civilized Behaviors in International Travel (hereafter Guidance) and the Convention of Chinese Citizens’ Civilized Behaviors in Domestic Travel in 2006 (Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MCT) Citation2021). In addition to these tourist-facing policies and procedures, the Requirements and Evaluation of Civilized Tourism Demonstration Units has been implemented to encourage the standardization of civilized business practice since then.

In line with the tenets of critical realism and Archer’s work, this research seeks to discover the cultural mechanisms of civilized tourism that are derived from the properties of civilized tourism at the structure level (i.e. the cultural system). Therefore, the research objectives are set as below:

To describe the ‘sayings’ of civilized tourism in the cultural system.

To identify the structural properties of civilized tourism and their situational logics.

To explain how these properties and their situational logics might have functioned to bring about the manifestation of civilized tourism.

Research design

Philosophical underpinnings

Archer (Citation1995), in agreement with Bhaskar’s critical realism (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2020), suggests that social reality can be studied through the methodological principle of analytical dualism. That is, civilized tourism can be studied at the structure level (i.e. social structure and cultural system) and at the agency level (i.e. social interactions and elaboration) separately. The interplay between the levels can then be analysed. It is from the analysis of the structure, agency, and their interplay, together, that an explanation of an emerging entity can be arrived at.

The research reported here only focuses on civilized tourism at the cultural system level. Its aim is to find underlying mechanisms of civilized tourism at the structure level that may have contributed to the emerging moral/ethical elaboration of civilized tourism in China so that a partial explanation of the manifestation of civilized tourism can be developed. Given the aim, abduction (interpreting the phenomenon of interest from a set of known concepts and/or theory(-ies)) and retroduction (reconstructing the basic conditions for anything to be what it is) were performed because both thought operations are more comprehensive ways of reasoning than deduction and induction in arguing and relating individual occurrences with general structures (Danermark, Ekström, and Karlsson Citation2019).

The study employed a two-phase of knowledge production. In phase one, the actual domain was considered with the use of observation and documents/literature. Abductive reasoning was performed to understand, in the framework of known concepts, what actually happened which may, or may not, have influenced events experienced by social actors e.g. tourists, tourism industry professionals, tourism organizations, and the public in general. In phase two, the ‘deep’ domain (i.e. less observable processes that condition the manifestation of civilized tourism in China) was studied through retroductive reasoning (Danermark, Ekström, and Karlsson Citation2019; Sayer Citation2010). The task was to generate the best possible explanation, based on the evidence, about mechanisms derived from the cultural system that have a tendency to cause the manifestation of civilized tourism in China.

Methodology

Phase one involved the use of covert observation of signs and posters in public places and tourist attractions and overt observation of the business settings of two tourism companies (one international hotel located in Dalian and Guilin Min Jian International Travel Agency Limited based in Guilin). Collaboratively, the researchers visited various sites in six Chinese cities and regions between 2018 and 2019, when the project was funded for, to collect data. In total, 138 photos were taken () based on their relevance to the phenomenon under investigation.

Table 1. Image data collection summary.

These observations facilitated the identification of two demi-regularities (Fletcher Citation2017) – the national promotion of 12 socialist core values (‘社会主义价值观’) and that of civilized tourism with an emphasis on tourist civility. These demi-regularities have informed further procedures that aim to understand the discourses of the ideas at the cultural system level (i.e. their systemic ‘sayings’). The socialist core values include prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony at the national level, freedom, equality, justice, rule of law at the societal level, and patriotism, dedication, integrity, and friendship at the individual levels. The term ‘社会主义价值观’ (socialist core values) was used to find relevant academic articles published between 2012 and 2018 in China’s national database of literature. This search generated 1265 academic articles, among which 24 papers were selected for further analysis based on their titles and abstracts that suggest a focus on ‘文明’ (civility or civilization), ‘文明旅游’ (civilized tourism), ‘游客文明素质’ and ‘旅游素质’ (tourist civility). These keywords were entered in the built-in search engine of MCT’s website to search relevant publications between 2019 and 2020. The search identified five items. In total, 29 articles were imported to NVivo for data analysis.

The primary concerns in phase two are twofold: (1) what innate property(-ies) has a causal power, and (2) when it is triggered, how the causation(s) expresses itself. (1) was fulfilled through a categorization strategy that involves the use of summative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) and framework analysis (Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003) whilst (2) was achieved through a connecting strategy with the use of critical discourse analysis (Bergström, Ekström, and Boréus Citation2017; Fairclough Citation2010; Potter Citation2009) and multimodal discourse analysis (Björkvall Citation2017; Wallace Citation2010).

When carrying out the multimodal discourse analysis on collected images, the researchers examined the visual sources from the interactive, representational, and compositional perspectives (Björkvall Citation2017). The focus was on how symbolic power relations are expressed, the use of colours, the depicted persons and objects, and the spatial organization of these elements in the images. The analysis of symbolic power relations involved an assessment of the camera angle in terms of the vertical perspectives in images as being from above, below, or eye-to-eye (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). The depicted persons and objects were analysed by looking at how they were presented in the horizontal perspective. A full-frontal perspective suggests inclusion whereas the rear and side views suggest exclusion. Colours and the spatial organization of the elements were analysed to establish the symbolic interactions among the depicted elements. The research team collectively developed interpretations or potential meanings of the images.

Sampled articles and the texts in the images were analysed by using critical discourse analysis. To understand the power relations between China’s central government and other social groups, two techniques were employed: (1) the transitivity analysis examined how relation between the government and other social groups was described; (2) the modality analysis evaluated the degree of certainty with which the Chinese government expresses itself. These tasks were carried out by the authors of the paper whose native language is Chinese.

Framework analysis was used to analyse 29 sampled articles and the authors’ descriptions of the compositional perspective of collected images by following the steps of familiarization, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, mapping, and interpretation (Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003; Ritchie, Spencer, and O'Connor Citation2003). This method’s dual coding capacity allowed substantive codes and theoretical codes to emerge. Substantive codes, such as ‘中国梦’ (China’s Dream) and national identity, captured what is being said in the data. Theoretical codes, such as CS_inconsistency [Cultural System_inconsistency], reflected the guiding effect of realist social theory on this research. The first author initiated the coding process and developed the framework, which were then reviewed by the other co-authors of the paper. The discrepancies of analysis among the authors were small. When they occurred, the authors discussed them and amendments were made accordingly.

Research evaluation

In case studies, triangulation is often used to reduce the likelihood of misinterpretation (Stake Citation2005). In this research, methodological triangulation, data triangulation, and investigator triangulation (Denzin Citation1978) were used to ensure the validity of the study. In terms of methodological triangulation, observation and documents (including images, academic sources, and Chinese government’s sources) were employed to ensure that the multiple perspectives of civilized tourism at the structure level are presented. Multiple methods were used to make sense of the data, wherein data triangulation was performed. Last but not least, themes identified in texts and the interpretations of images were compared and reviewed among the researchers.

Further, Maxwell (Citation2012) argues that the validity of a study’s conclusion does not only depend on if specific procedures are used and how they are used, but also on how the actual conclusions are drawn by using the procedures in the given context. To ensure the validity of the study’s conclusions, the research team kept logs of commentaries throughout the argumentation development process. The exercise of recording our situated voices is vital to prevent potential slipping into the relativist philosophical position (Li Citation2022), thus avoiding the possibility of epistemological reductions of knowledge (Bhaskar Citation2011).

Findings

This section reports findings that address research objectives 1 and 2 (outlined in section ‘Contextualization’). Section ‘The sayings of civilized tourism’ presents what ‘civilized tourism’ entails overall at the structure level. Section ‘The structural properties of civilized tourism’ reports the characteristics that distinguish civilized tourism from other related concepts and ideologies (i.e. the structural properties of civilized tourism). The working of these properties is identified and reported in section ‘Situational logics’. The findings are arrived at through abductive thought processes. That is, civilized tourism is re-described in the frame of the theoretical discussions outlined in the literature review sections so as to shift from the empirical evidence in the actual domain to facts in the real domain.

The sayings of civilized tourism

‘Civilized tourism’ is not comprehensively analysed as a concept in sampled tourism research papers, but is primarily used vis-à-vis tourist behaviour i.e. explicitly linking with ‘道德’ (moral or ethical) and ‘不道德’ (immoral or unethical). outlines the matters, their frequencies of reference, and some examples from the MCT publications. The most frequently mentioned matters are those related to civilized tourism voluntary initiatives in terms of volunteers, their participation, and their contributions in promoting and serving the civilized tourism movement. This is followed by references to legal regulations, conventions, and procedures to regular tourism businesses’ practices, the practice of tour guides, and tourist behaviours. In addition to the events that promote civilized tourism, accounts about tourist behaviour are an important category. The themed terms in the texts appear to be random. This may suggest that the landscape of civilized tourism – a new idealization – is in the process of forming.

Table 2. Matters in civilised tourism.

The structural properties of civilized tourism

Civilized tourism-civility

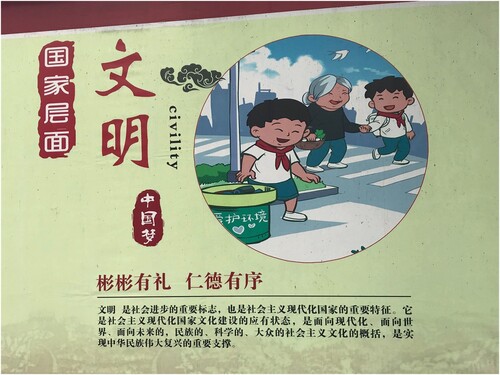

Civilized tourism is described as ‘a landscape of beautiful scenery’. The phrase ‘beautiful scenery’ is also used for the notion of civility. Civility is said to be ‘the most beautiful scenery’. These words are seen in a poster displayed in an underground bypass in Dalian (), in a display in the premises of the Travel Agency in Guilin, and in another travel agency’s educational leaflet for its customers.

Figure 2. ‘Civility is the most beautiful scenery.’Footnote2

Based on sampled articles, the notion of civilized tourism emerges from the central government’s approach to the country’s civility development. Acting upon Chairman Xi’s speech on developing civilized tourism, a series of events took place nationwide in 2009 (MCT Citation2019). Likewise, responding to Chairman Xi’s call for not to waste food in 2020, the tourism sector includes various initiatives to promote sensible food consumption in its civilized tourism agenda (MCT Citation2020, November 5).

Civility or civilization (‘文明’) appeared 903 times in the sampled articles. The ideology of ‘文明’ has been discussed in conjunction with the aspects of the society, including ‘political’, ‘cultural’, ‘industrial’, ‘familial’, ‘Chinese’, ‘ecological’, ‘tourism’, and ‘travel’. Ecological civility, tourism civility, and travel civility are also evident in the collected images. Further analysis of civility reveals its linkages with other ideas. Civility is discussed with regard to other five main idealizations: Chinese Socialism, Chinese tradition (including Confucianism and Daoism), Marxism, and Western capitalism, and Western value system. Some examples are:

The originality and meaning of ‘civility’ in the Chinese tradition are discussed in two articles (Xu Citation2014; Xu Citation2017) – ‘civility’ documented in ancient Chinese literature as inheriting the traditional culture through a course of action that is derived from observing the signs of the sky, the status of one possessing knowledge vis-à-vis that of the savages, and social etiquettes.

Agreement is sought from the Western school of thought on ‘civility’, which refers to a society that is peaceful as opposed to one that faces wars … and is a periodical progress of societal development. Xu (Citation2014) writes: ‘civility’ in the West and that in China share the same ground – it is a relational concept describing a status of societal development that is peaceful and civilised as opposed to ‘wars’ and ‘savage’ (55).

This consistency of ‘civility’ with Marxism is overwhelmingly present.

In multiple articles, civility is debated on with references to liberal movements in France, the democracy discourse in the United States, and industrial civilization in Europe.

Civilized tourism – civility – China’s Dream

While civilized tourism emerges from the central government’s approach to the country’s civility development, both notions are integral parts of China’s Dream. This Dream is concerned with the revival of the Chinese nation – the vision that the country has for the future. Its underpinning values are named socialist core values which are advocated nationally. The values are: prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony at the national level, freedom, equality, justice, rule of law at the societal level, and patriotism, dedication, integrity, and friendship at the individual level.

One image about civility is selected to present here () because of the interesting insights into the dynamics of this cultural item that are expressed explicitly and implied implicitly with the use of symbolic items, colours, and the sizes and organization of depicted components. It is a photo of a poster by a district committee (a local governmental agency) in Guilin, which is a governmental body. This poster is approximately 5 metres wide and 3 metres high, presented in a residential area in the city centre.

Figure 3. Civility.Footnote3

As can be seen in , the left top area of the poster is fully occupied by nine Chinese characters (from left to right): ‘国家层面’ (the national level), ‘文明’ (civility or civilization), and ‘中国梦’ (China’s Dream). ‘文明’, in particular, are displayed in larger size compared with other words. Red is used to draw attention. The two characters ‘文明’ (civility or civilization) are written vertically – the traditional way of writing Chinese. Likewise, the ‘national level’ (‘国家层面’) to their left and ‘the Dream of China’ (‘中国梦’) underneath them are printed vertically. In particular, the presentation of the Dream of China gives a strong sense of Chinese calligraphic tradition. There are only nine characters, but they occupy a relatively large area of this poster, and are depicted in red. Such a presentation immediately brings out what this poster is about – civility is a national ‘thing’ and an element of China’s dream.

Civility is explained in black at the bottom of the image as an important indicator of societal development, an important feature of the development of a modern socialist country, and an important pillar of the revival of China. Above the explanatory statement, the two 4-word phrases (in red) positioned refer to ‘礼’ (etiquette), ‘仁’ (benevolence), ‘德’ (virtue), and ‘序’ (order) which are frequently seen in Confucian literature and contemporary writing about Confucianism.

Civilized tourism – civility – social etiquette

Compared with the sayings of ‘civility’ that is at a relatively higher level of ideological construction, ‘civilized tourism’ is a notion that is closer to the social lives of individuals. Civilized tourism is ‘operationalized’ through detailed (primarily) behavioural and (to a lesser extent) cognitive instructions that guide or educate all Chinese citizens to follow public etiquette in their pursuit of leisure and holiday activities. Indeed, one core element of civilized tourism is ‘礼’ (Lĭ, etiquette). Lĭ appeared 12 times in sampled tourism academic papers, 188 times in academic papers on civility, and 11 times in the MCT publications. The doctrine of ‘礼’ evolves from a wider social and cultural value system in China’s history. It includes the volumes of Zhōu Lĭ (<<周礼>>), Yí Lĭ (<<仪礼>>), and Lĭ Jì (<<礼记>>), which started to emerge from BC 1046 (Xu Citation2017). They were formed based on the rules and standards that guided social interactions between people. ‘Lĭ’ still plays a noticeable ideological role in contemporary China. This is evident in sampled academic writings wherein China is referred to as ‘礼仪之邦’ (a state of etiquette). This historical and socio-cultural consistency is also reflected in embedded coding of ‘tradition’ in passages coded under ‘civilization’ and in those coded under ‘civilized tourism’.

Situational logics

Protective and corrective logics

‘Civility’ is protected through (1) synthesizing common grounds across the Chinese tradition, Marxism, the Western view of civility, which indeed demonstrates a systemic consistency, and (2) corrective moves wherein the other versions are criticized and rejected accordingly (i.e. systemic contradiction). The consistency of the idealizations of civility is reflected in the agreement that ‘civility’ is concerned with societal progresses that are related to peace. This item’s consistency with Marxism is overwhelmingly present. Not surprisingly, the inconsistencies appear to be based on the Marxian critique of civilization in capitalism (Zheng Citation2015) and Chinese socialist critique of civilization in ancient Chinese societies that were built on hierarchical social classes (Wan Citation2018).

Protection through sustaining tradition

The ideology of civility is protected through a discourse of maintaining Chinese culture. Returning to the poster illustrated in , ‘文明’ (civility or civilization) are displayed in red and in a larger size compared with other words. These two characters are written vertically – the traditional way of presenting written Chinese. Likewise, ‘国家层面’ (the national level) to their left and ‘中国梦’ (China’s Dream) underneath them are printed vertically. In particular, the presentation of ‘中国梦’ gives a strong sense of Chinese calligraphic tradition. This is reinforced by ‘礼’ (Lĭ, etiquette), ‘仁’ (benevolence), ‘德’ (virtue), and ‘序’ (order) which are frequently seen in Confucian literature.

Protection through visioning prosperity

In , civility is explained in black at the bottom of the image as an important indicator of societal development, an important feature of the development of a modern socialist country, and an important pillar of the revival of China. The explanatory statement mentions ‘socialism’ three times, ‘facing’ three times, ‘the country’s’ twice, and (Chinese) ‘nation’ twice. The dynamics or complexity of civility is reflected in the words of (facing) ‘modernization’, ‘the world’, ‘the future of socialist culture defined by nationalism, sciences, and the embracing by the masses’. Thus, in essence, in this poster civility composes multiple aspects of enduring societal changes and that civilization derived from the past, yet somehow is identifiable at the present while anticipating a futuristic and progressive vision to aim at.

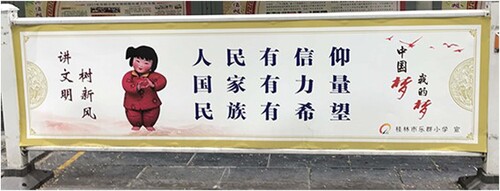

Indeed, as shown in and , all the depicted characters are smiling, creating a happy atmosphere which is co-presented with words or phrases, such as ‘the people have beliefs’, ‘the country has the strength’, and ‘the nation has a hope’ in . In , the carton image positioned at the top right corner occupies a significant space in the poster – a happy image is portrayed: one young boy is helping an old lady to cross the road while the other boy is putting rubbish into a bin, on which it says ‘protect the environment’. Thus, it shows desirable social interactions between people as well as between humans and the environment. An interesting detail is the red neckerchief that the young boys wear. Differing from the ties in general, they are called 红领巾 in Chinese and worn by the pupils in primary schools. The wearing of them implies one’s cognitive subscription to socialism and the Communist Party.

Figure 4. 中国梦 我的梦 (China’s Dream, My Dream).Footnote4

Protection through cultural inclusivity and exclusivity

Civilized tourism and civility as cultural items are depicted in textual and pictorial symbols in cultural inclusive and exclusive manners. Interestingly, in all drawings sampled, the eye-to-eye level contact is witnessed, giving rise to an inclusive perspective. This perspective is further confirmed and strengthened through (1) the use of ordinary people in the drawings acting out their ordinary activities, such as crossing the road, looking after one’s parents, and harvesting crops, (2) the use of ‘I learn and practise’ and ‘our value’ in the posters (e.g. ), (3) the use of ‘the Chinese nation’ and ‘the Chinese tradition’ in sampled academic writings, and (4) the persuasion of ‘happiness for all’.

The inclusivity goes hand-in-hand with exclusivity. Do’s and Don’ts are explicitly displayed in public spaces. Socially accepted acts are deemed civilized and good behaviours whereas the unacceptable acts are said to be ‘uncivil’, ‘immoral’, ‘unethical’, and ‘bad’. Messages and images of uncivilized behaviours, such as ‘don’t litter’, ‘don’t inscribe your name on the artefact’, and ‘don’t jump the queue’ are made available to the public at tourist sites. These types of behaviours are deemed unacceptable and uncivilized in the society and, thus, need to be removed from an orderly and civilized society by means of correcting such disorderliness. For example, tourists have been invited to participate in virtual events such as sharing video recordings of civilized or uncivilized tourist behaviour on social media. Legal and administrative procedures are also put in place to target uncivilized behaviours. Some of the mechanisms are the country’s blacklists of tourists who have been convicted for behaving badly, and tourist guiding services provided by civilized tourism volunteers at the attractions.

captures the socio-cultural interaction between a civilized tourism volunteer and a visitor to Senmiao Eco-resort. The dress-code of the volunteer is very professional while her posture is welcoming, demonstrating trained social etiquette of standing, greeting, and directing. Looking at the surroundings of this social interaction, the institutional symbol of China Tourism Volunteers is noticeable in the red poster on the wall and on the tablecloth. Matters (b) and (d) (in ) are also found in whereby ‘文明旅游公约’ (Civilized Tourism Convention) can be seen in the resort’s poster on the left and the red poster on the wall. The Convention outlines not only culturally accepted cognitive mindsets, such as ‘Love Ningxia’ in , ‘Love the country’, ‘Love Guilin’ in other images. It also reminds people to stay safe while travelling and to be mindful of one’s civility i.e. to engage in behaviours that are socially acceptable and not to engage in those that are socially unacceptable.

Figure 5. Social interactions in civilized tourism.Footnote5

The social agreements are slightly contextualized for the targeted group. For instance, the version displayed in the resort’s poster () expresses ‘Love Ningxia’, instead of ‘Love the country’, which seems to target the domestic tourists. Likewise, ‘Convention for Domestic Chinese Tourists’ is displayed at the public park Two Rivers and Four Lakes in Guilin. In contrast, in a travel agency’s educational leaflet for their customers who are travelling abroad, cartoon drawings of international attractions, such as the Eiffel Tower in France and the Parliament building in London, are used with short texts about Do’s and Don’ts. These words are consistent with those in the generic Convention, but also in line with the Guidance for international travel by the Chinese.

Protection through social inclusivity

The central CO and its subdivisions are most frequently mentioned, followed by the civil group of civilized tourism volunteers. Other collectivities mentioned are tourism sector committees and associations, legislation and regulatory bodies, tourism companies, media, the education sector, the representatives of the National Congress of People, and the members of the National Committee of People’s Republic of China. Volunteers’ involvement has been of great significance at the forefront of civilized tourism (Matter (a) in ). Their roles are said to be to ‘disseminate’ leaflets, ‘promote’ civilized tourism, ‘demonstrate’ public etiquette, and ‘provide’ direction and information to tourists. Therefore, there seems to be a dual social inclusion – a top-down inclusion of institutional involvements coupled with a ‘bottom-up’ inclusion of individuals wherein the volunteers promote and demonstrate civilized tourism to the individual tourists.

A realist explanation

This section addresses research objective 3 outlined in section ‘Contextualization’. It aims to provide the best possible evidence-informed explanation about the working of the structural properties of civilized tourism in China and their situational logics that has the tendency to generate its social practice. In this retroductive thought exercise, three fundamental questions are to be answered: (1) What properties and internal relations must exist for civilized tourism to be what it is? (2) What situational logics must exist for civilized tourism to exist? (3) How they might have worked to result in the emergence of civilized tourism at the structure level?

To answer question (1), civilized tourism is arguably a form of utopian flourishment of Chinese society. As evidenced in the data, its existence is in relation to other ideas i.e. civility, China’s Dream, and social etiquette. The analysis shows that civilized tourism has its root in civility which is one of the twelve socialist core values advocated by the Chinese government. While civility carries properties that are closely related to China’s Confucian heritage (e.g. etiquette, benevolence, virtue, and order), it is also said to be ‘the most beautiful scenery’ now. This is reinforced by the saying that civilized tourism is ‘a landscape of beautiful scenery’.

To answer question (2), the situational logics that must exist for civilized tourism to exist are (a) protective and corrective logics concerned with civility, (b) the protective logic of civilized tourism through sustaining tradition, (c) that of visioning prosperity, (d) that of cultural inclusivity and exclusivity, and (e) that of social inclusivity. How these logics might have functioned to cause the emergence of civilized tourism at the structure level are elaborated on as follows.

With regard to the working of situational logics (a) and (b), civility in the current Chinese socialist movement partially disagrees with some Western positions on liberty, freedom, and democracy. One may have some concern over the use of ‘civilized’ in this Chinese case given their colonizing connotations (i.e. ‘civilizing’ the natives). However, in the current political-driven socio-cultural movement in China, ‘civility’ emphasizes not only inheriting the long-lasting eminent Chinese civilization – the tradition lived in and evolved from the country’s 5000-year history (Xu Citation2017), but also contextualizing the Marxian tradition so as to promote China’s societal development in accordance with the needs and characteristics of the contemporary society (Wan Citation2018; Zheng Citation2015). This originality of ‘civility’ and ‘civilization’ in the Chinese context and that of tourism being rooted in the nation’s tradition and history is also seen in Li, Hazra, and Wang’s (Citation2023) study, who report that

All Chinese hotel managers proudly elucidated their relationship with guests in a mindset of Confucian tradition of hospitality that links to civilisation … ‘beginning with Lao Tzu’s moral classics and Confucianism, China has a strong cultural background to support our development … in the hotel industry’ … ‘in our hotel, we provide a service that follows our civilised way of doing things, which itself is a strong characteristic of our Chinese nation.’ (9)

With regard to the working of situational logic (c), the ideations (i.e. civilized tourism and civility) emphasize commonly shared welfare and a vision of utopianism that everyone’s well-being is protected. This reminds us of the naturalization strategy of ideological manipulation that Archer (Citation2008), Dowding (Citation2006), and Lukes (Citation2005) have discussed. ‘中国梦’ is translated into English as ‘Chinese Dream’ in China and in Weaver (Citation2015). We use ‘China’s Dream’ because the inherent idealization of this social construct originates from the Chinese Communist Party, conveying the values and vision that this political ruling party of China advocates. The values and vision conveyed in this metaphor are often described as one that is also held by all the Chinese people in the Party’s communication to the public. The utilitarian approach is normal in any ideological discourse.

However, the Dream does not originate from all Chinese citizens. This is evident in whereby two young characters wear the Communist red neckerchiefs, which strongly conveys a sense of a happy future under the leadership of the Communist Party. Indeed, as explained in one collected image, this Dream is a 200-year project from 1921 when the Chinese Communist Party was established to 2049. It aims to develop the communist country into one with Chinese characteristics through the construction of political civilization, economic civilization, cultural civilization, societal civilization, and ecological civilization.

Therefore, from the academic perspective (and perhaps the linguistic too), ‘Chinese Dream’ does not capture the contextual and political nature of the construct well. Equating the Party’s Dream with that of the population is a verdict of ontological conflation. By shifting the focus to the well-being of people, the idea is presented to the masses as the natural order of affairs whilst any biased propositions related to Communist tenets fade into the background. Thus, it is through this naturalization strategy of ideological manipulation a ‘shared’ culture of civilized society where tourism resides is created. This ‘shared’ culture is indeed something that one particular group does to other social groups as Archer has commented (Archer and Elder-Vass Citation2012).

With regard to the working of situational logics (d) and (e), inclusivity, in particular, features the discourse of civilized tourism. The inclusive strategies evidenced in the data denotes a national reach. The ideations of civility development and civilized tourism development are both rolled out nationally. This is not only observed by the researchers in the cities and regions visited but also evidenced in sampled publications. The reach is realized through (1) vertical administrative reach, (2) horizontal cross-sectoral reach, and (3) vertical sectoral reach. The first type of reach stems from the CO, which was established in 1997 and responsible for coordinating and promoting the country’s spiritual/cultural development. The central CO provides instructions which are then followed by its branches at provincial, metropolitan, and local levels.

The second type of reach is concerned with inclusive participation from a range of social groups. In particular, initiatives that advocate the Chinese tradition of Lǐ or etiquette are encouraged across different sectors of the society. As Xu (Citation2017) remarks, public etiquette education needs to be strengthened and made available to the whole population so as to continue the Chinese tradition of Lǐ and to maintain the reputation of country’s long history and civilization – a state of etiquette. Xu maintains that public etiquette education and training need to be provided in major sectors including schools, hospitals, tourism, enterprises, urban management bodies, and banking with a particular focus on persons who work at the front line of public services, transport stations, ports, airports, hotels, travel agencies, hospitals and so forth. Furthermore, a variety of effective media is to be utilized to promote public etiquette learning at libraries, recreation places, museums, cinemas, community centres, schools, parks, and other public spaces.

Thirdly, within tourism, there is a vertical sectoral reach. It is described as a six-in-one model of promotion system: the governmental agencies of the tourism sector – the industry’s associations – businesses – media – volunteers – tourists. The connections or the nature of engagement between these six stakeholder groups are primarily top-down. That is, the governmental agencies of the tourism sector follow the instructions or guidelines from the central CO and initiate contextualized events and/or themes to promote civilized tourism and public etiquettes in tourism. Public–private collaborations with use of media are sought to promote and/or perfect civilized tourism practice.

Conclusion, implications, and future research

This paper has argued that the goal of scientific work in social sciences is to find the mechanisms derived from structure and agency (so that solutions can be sought to influence the processes for the betterment of humanity); however, in the discourse of value-laden tourism research, knowledge about the mechanisms that manifest morally guided tourism (including ethical tourism and civilized tourism) is very limited. The empirical research reported in the paper has tapped into the generative powers of civilized tourism at the structure level. It has identified the structural properties of civilized tourism and their situational logics, and provided a realist explanation (at the structure level) about how the properties and logics work to bring about the discourse of civilized tourism in China.

As a form of utopian flourishment of Chinese society, civilized tourism’s existence is in relation to other ideas i.e. civility, China’s Dream, and social etiquette in Confucian tradition. These ideations provide a condition for civilized tourism to exist. The study has revealed five situational logics that must hold for civilized tourism to exist, namely (a) protective and corrective logics concerned with civility, (b) the protective logic of civilized tourism through sustaining tradition, (c) that of visioning prosperity, (d) that of cultural inclusivity and exclusivity, and (e) that of social inclusivity. Situational logic (a) derives from the (in)consistency of civility. Logics (c), (d), and (e) come strongly from the ideations of both civility and China’s Dream. All these logics function to co-determine what civilized tourism is about as ‘sayings’ in the cultural system. These findings make a great contribution to our understanding of what civilized tourism means conceptually in the cultural system and its situational logics that condition practice.

It is learned that civility tourism development in China is a government-initiated societal movement. The practical implication of the finding is: policymakers in China are to consider creating an environment that facilitates educational efforts in different social settings (e.g. schools, families, and communities) to facilitate morally/ethically directed social interactions. For organizations, initiatives can be, for example, different training courses and corporate social responsibility activities. They are to facilitate tourism industry professionals and other social actors in their respective social, economic, and/or political positions to acquire civility awareness and to strengthen personal practice of Lĭ. Last but not least, ideations need to be conveyed in such a way that people can resonate with the idea of civility and civilized tourism.

One limitation of the study is attributed to epistemological relativism. The research findings are the researchers’ attempt to understand civilized tourism. They represent the positions that the researchers hold to explain the reality of civilized tourism at the structure level; they do not determine the reality. As a transitive dimension of knowledge, the positions are subjective, value-laden, contingent, and improvable, but they are nevertheless the best possible explanation that the researchers can draw from the empirical evidence and existing theoretical knowledge.

The second limitation of the study lies in its scope – focusing on the cultural structural level. Although civilized tourism practice is conditioned by the past and is engineered by the protective and corrective situational logics of the idealizations and cultural manipulations (i.e. power, inclusivity, and exclusivity) across time and space, it is the enduring working of socio-cultural interactions that is ultimately responsible for the germination of the seeds of systemic inconsistency and consistency. The sharing of civilized tourism is contingent i.e. subject to social actors’ engagement with the sayings of civilized tourism and socio-cultural interactions among them. Thus, future research is to examine the extent to which civilized tourism is adopted and the degree to which this idealization is accepted and practiced by individual social actors.

Finally, the civility development for enhanced civilization in China is heavily promoted and rolled out nationwide whereas ‘civility’ is rarely mentioned in English-speaking countries, such as the United Kingdom. This is not to say that socio-cultural development is not regarded as important outside the jurisdiction of China. China’s approach in advocating civility and its development has a strong link to its own enduring history and civilization. While civility development in China is highly political-driven, it has possibly accelerated a rising movement of nationalism in the country, the effects of which on the international communities are yet to be seen and measured.

Acknowledgements

The project team is grateful for the financial support from Bath Spa University that provided devolved Higher Education Quality Research funding (award no. 116) and seed fund to finance data collection. The team would like to thank Guilin Min Jian International Travel Agency Co., Ltd. for its full support and participation in the research, and Andrew Craig Lowman for his assistance to improve the readability of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data linking: Li, Li (2021) Resource list on civility and civilized tourism. BathSPAdata. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.17870/bathspa.16997170.v1

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Li Li

Li Li – A Reader in Management with research interest in realist analysis of ethical tourism, and social and organizational changes.

Jing Wang

Jing Wang – An Assistant Professor with research interest in destination management, tourism policy and planning, and civilized tourism.

Samrat Hazra

Samrat Hazra – A Lecturer in Tourism Policy and Developments with research interest in ethics, stakeholder networks, and sustainable destination development.

Notes

1 Editor’s note: The phrase ‘civilised tourism’ is a direct translation of a Chinese concept equivalent to that which English speakers might call ‘responsible tourism’.

2 The photo was taken at a Metro station in Dalian. The poster’s issuer is unknown. Its approximate dimension: (45 cm × 60 cm.)

3 The photo was taken in Guilin. The poster is issued by Xiufeng District Committee of Guilin and displayed in a street in the Guilin city center which is a significant tourist area of the city, but also has a high level of density of local residents. Its approximate dimension: 500 cm × 300 cm.

4 Poster issuer: Guilin Lequn Primary School. Taken in the street outside the school, Guilin.

5 Taken at Senmiao Eco-resort, Yinchuan.

References

- Ajzen, I. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behaviour.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process 50 (2): 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Archer, M. S. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. 2000. Being Human: The Problem of Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. 2008. Culture and Agency: The Place of Culture in Social Theory. 2 edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. 2012. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. 2015. “Introduction: Other Conceptions of Generative Mechanisms and Ours.” In Generative Mechanisms Transforming the Social Order, edited by M. S. Archer, 1–26. London: Springer.

- Archer, M. S., and D. Elder-Vass. 2012. “Cultural System or Norm Circles? An Exchange.” European Journal of Social Theory 15 (1): 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431011423592.

- Bandura, A. 2001. “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective.” Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1.

- Bandura, A., G. V. Caprara, C. Barbaranelli, C. Pastorelli, and C. Regalia. 2001. “Sociocognitive Self-Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Transgressive Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 80 (1): 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.125.

- Barnes, B. 1981. “On the ‘Hows’ and ‘Whys’ of Cultural Change (Response to Woolgar).” Social Studies of Science 11 (4): 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631278101100404.

- Bergström, G., L. Ekström, and K. Boréus. 2017. “Discourse Analysis.” In Analysing Text and Discourse: Eight Approaches for the Social Sciences, Chapter 8, edited by K. Boréus and G. Bergström, 208–241. London: Sage.

- Bhaskar, R. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. New York: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. 2009. Scientific Realism and Human Emancipation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. 2011. Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. 2015. The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. 2020. “Critical Realism and the Ontology of Persons.” Journal of Critical Realism 19 (2): 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2020.1734736.

- Bi, Y., L. Li, and Y. Zhang. 2019. “基于MOA模型的不文明旅游行为影响因素与对策建议研究.” Resource Development & Market 35 (9): 1203–1208. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-8141.2019.09.015.

- Björkvall, A. 2017. “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In Analysing Text and Discourse: Eight Approaches for the Social Sciences, Chapter 7, edited by K. Boréus and G. Bergström, 174–207. London: Sage.

- Bloor, D. 1981. “The Strengths of the Strong Programme.” Philosophy of Social Sciences 11: 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/004839318101100206.

- Botterill, D., S. Pointing, C. Hayes-Jonkers, A. Clough, T. Jones, and C. Rodriguez. 2013. “Violence, Backpackers, Security and Critical Realism.” Annals of Tourism Research 42: 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.01.007.

- Bunge, M. 2004. “How Does It Work? The Search for Explanatory Mechanisms.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 34 (2): 182–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393103262550.

- Buzar, S. 2015. “An Analysis of the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism in the Context of Corporate Social Responsibility.” Acta Economica Et Turistica 1 (1–2): 1–112. https://doi.org/10.1515/aet-2015-0004.

- Dai, Y. J., and F. Z. Qin. 2001. “论我国旅游伦理思想及其建设.” 思想战线. 27 (4): 48–50. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn/1001-778x.2001.04.013.

- Danermark, B., M. Ekström, and J. Ch. Karlsson. 2019. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Denzin, No. K. 1978. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Dowding, K. 2006. “Three-Dimensional Power: A Discussion of Steven Lukes’ Power: A Radical View.” Political Studies Review 4 (2): 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9299.2006.000100.x.

- Fairclough, N. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Harlow: Longman.

- Fennell, D. A. 2018. Tourism Ethics. 2nd edn. Bristol: Channel View.

- Fletcher, A. J. 2017. “Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology Meets Method.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (2): 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401.

- Gao, M., and W. He. 2020. “The Model Construction and Empirical Study About the Impact of Civilized Tourism on National Cultural Strength – Taking Chinese Tourists Travelling to Cambodia as an Example.” Tourism Forum 13 (4): 33–36. https://doi.org/10.15962/j.cnki.tourismforum.202004033.

- Hartwig, M. 2007. Dictionary of Critical Realism. London: Routledge.

- Hsieh, S., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Hu, G. D. 2008. “旅游者道德弱化行为的推拉 (The Push-Pull Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Tourists’ Weakened Morality).” Journal of Chongqing Normal University 5: 96–100. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-0429.2008.05.016.

- Huang, L. P. 2019. “The Formation Mechanism of Youth Tourists’ Civilized Tourism Behavior: An Extended Model Based on VBN Theory and TPB Theory.” Unpublished Master’s Dissertation. Hunan Normal University.

- Huang, S., R. ven der Veen, and G. Zhang. 2014. “Editorials: New Era of China Tourism Research.” Journal of China Tourism Research 10: 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2014.952909.

- Huang, Y., Q. Zhang, and S. Luo. 2022. “Research on the Coordination of Tourism Industry Development and Ecological Civilization Construction in Western Ethnic Areas.” Ecological Economy 38 (2): 130–136.

- Hunter, C. 1997. “Sustainable Tourism as an Adaptive Paradigm.” Annals of Tourism Research 24 (4): 850–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00036-4.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Lau, R. W. K. 2009. “Revisiting Authenticity: A Social Realist Approach.” Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2): 478–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.11.002.

- Lawson, T. 2019. The Nature of Social Reality: Issues in Social Ontology. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

- Lee, H. Y., M. A. Bonn, E. L. Reid, and W. G. Kim. 2017. “Differences in Tourist Ethical Judgment and Responsible Tourism Intention: An Ethical Scenario Approach.” Tourism Management 60: 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.003.

- Li, Y. 2018. “Study on the Relationship Between Ecological Ethics and Tourism Civilization Behavior Intention of Forest Tourists.” Unpublished Master’s Dissertation. Central South University of Forestry and Technology.

- Li, L. 2022. “Critical Realist Approach: A Solution to Tourism’s Most Pressing Matter.” Current Issues in Tourism 25 (10): 1541–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1944994.

- Li, Y., and S. W. Cheng. 2016. “关于’文明旅游’研究的认识、探索与反思.” Tourism Tribune 31 (7): 3–4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-5006.2016.07.002.

- Li, L., S. Hazra, and J. Wang. 2023. “A Realist Analysis of Civilised Tourism in China: A Social Structural and Agential Perspective.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 7 (1), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100411.