ABSTRACT

The Morphogenetic Régulation approach (MR) contributes to the Morphogenetic Approach by explaining the material and ideational origins of change and stasis in agency, structure, and culture. In this paper, we focus on the expressive quality of ideas and systemic persistence in three research projects. The first demystifies inclusive governance and its adverse impacts. It shows how, contrary to institutions of governance, inclusiveness is not simply a norm but actually the explication of corporate agents’ ideas about rational choice institutionalism which leads to adverse impacts on vulnerable groups and ecologies known as adverse inclusion. The second investigates the role of ideas as adequacy and self-explication in guiding Palestinian actors’ actions towards the deepening of neoliberalization in Palestine. The third explains the relevance of the systemic persistence problematique for understanding how three juxtaposed themes – Web2, Web3, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) – are shaping the political economy and infrastructure of the Internet.

Introduction

The analytical dualism of Margaret Archer’s Morphogenetic Approach (MA) has been subjected to various critiques from within critical social science literature. Some have argued that it implies a reductionist view of social phenomena that conceives of them wholly in terms of interactions between individuals (Hay Citation2002, 125; King Citation1999, 222). Others, meanwhile, have asserted its compatibility with Giddens’ structuration theory (Stones Citation2001, 183). Knio, meanwhile, accepts the core tenets of analytical dualism as pertains to the structure-agency debate, but innovates atop Archer’s Morphogenetic Approach via a particular application of Spinozian immanent causality to deepen the approachs’ analytical potential for understanding social change. Specifically, the Spinozian Doctrine of Parallelism and a detailed account of the expressive role of ideas are operationalized to account for the relationship between structures and cultures, as well as their interactions with people (Knio Citation2018). In so doing, the so-called Immanent Causality Morphogenetic Approach (ICMA) comprises an innovative reworking of Archer’s MA with a significant contribution to both the material-ideational and transcendence-immanent ontological debates as pertain to their analytical operationalization in morphogenetic explanations of social change.

This article contains a summary of the content of three presentations given by the authors at the 2022 Conference of the International Critical Realism Network, where three research projects were presented that employ Knio’s Immanent Causality Morphogenetic Approach (French Regulation) (ICMA (FR)) (Knio Citation2018; Citation2020) to different pertinent case studies. Hereafter, ICMAFR is referred to as Morphogenetic Régulation (MR) and applies to the first and last case study while the second case study is an application of ICMA. The intention of this paper is to explain three key concepts contained within the model, as well as its practicality, which, it is argued, represents an important contribution to furthering the Critical Realist school of thought. These concepts are ideas as self-explication, ideas as adequacy, and systemic persistence. ICMA and Morphogenetic Régulation is a model of social change derived from an analytically rigorous and consistent engagement with CR’s emergentist ontology. This is further specified through a unique position in four key ontological debates: individual-group, structure-agency, material-ideational, and transcendence-immanence (Knio Citation2018; Citation2023). In fleshing out many of the philosophical presuppositions and modern theoretical interpretations of the material-ideational and transcendence-immanence debates (Knio Citation2018; Citation2020; Citation2023), the ICMA linked Archer’s Morphogenetic Approach (MA) (Archer Citation1995), a long-standing model of social change in CR, with the Spinozian notion of immanent causality as explained by the doctrine of parallelism (Knio Citation2018; Citation2023). With that in mind, the ICMA (and thus Morphogenetic Régulation) fully accepts the tenets of MA’s analytical dualism in terms of structure-agency and the group-individual debates but problematizes its engagement with the material-ideational and transcendental-immanence debate with the intention to provide a more nuanced diachronic and synchronic analysis of the three levels of the morphogenetic cycle.

The ICMA was applied to the French Regulation school of institutional analysis (Boyer and Saillard Citation2002). FR’s heralded concepts of the Regime of Accumulation (ROA); the Mode of Regulation (MOR); and Institutional Forms (IF) have entailed a significant contribution to the pursuit of providing detailed conceptual, theoretical, and empirical analyses of capitalism and its transformations (Boyer, Durand, and Mair Citation1997). Yet, traditional FR analysis is largely de-ontic in its orientation and Morphogenetic Régulation aims to provide stratified and emergentist FR analysis depicted across the Conditioning, Interaction, and Elaboration phases of a morphogenetic cycle; and augment the approach with a solid metatheoretical grounding (Knio Citation2020).

The first section of this article will briefly overview the core ontological tenets of the MR model and comment on its methodological innovations which contribute to Archer’s MA While it is impossible to cover all of the concepts evoked within ICMA/MR, the second section will further develop the three concepts which have been applied to the research projects in the third section of the paper: ideas as self-explication, ideas as adequacy, and systemic persistence. The third section will explore the utility of each concept for the empirical theme it is applied to, respectively. This is through an analysis which is structured in terms of a background of necessary empirical information specified to zoom in on the concept being operationalized from the aforementioned three. It follows that the first project focuses on ideas as self-explication, and contains reflections about why this concept is of particular value for research on the institutional origins of inclusive governance and its adverse impacts known as adverse inclusion. The second continues the application of self-explicating ideas in addition to the use of ideas as adequacy in explaining the unfolding of neoliberalization processes within the National Development Plans of the Palestinian Authority over the past twenty-five years, as well as the role of international actors in shaping these processes through their development interventions. The third and final part of the analysis focuses on systemic persistence in the T5-T1 period where new morphogenetic cycles come into being. The case is a research project aiming to provide a philosophically substantivist French Regulation (FR) analysis of the political economy of the Internet in the advent of exponential developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology and the emergent Web3 movement. The paper will then conclude with an executive summary and some parting remarks. This analysis not only validates the ICMA and Morphogenetic Régulation’s contribution to MA and CR as a whole, but also shows the value added of the three concepts overviewed for the particular empirical fields under investigation: inclusive governance, neoliberalizing processes in Palestine, and the political economy of the contemporary Internet.

The ICMA(FR): an innovative theoretical and methodological framework

The ICMA(FR) is concerned with the ‘systemic persistence’ research problematique and those necessary and internal relations that persist through a morphogenetic cycle despite their contingent expression in a variety of forms (Archer Citation1995). These relations are omnipresent insofar as they constitute the foundational context that conditions the parameters that surround the potentialities for social action, expressing themselves as contextually specific attributes that agents form and navigate their reflexivities in relation to. They also possess independent properties that represent their own causal powers that exist outside of the capacity for them to be expressed through human deliberation and action (Archer Citation2020). That is, objects have their own dispositional capacities. These necessary and internal relations are the object of research because they are what ascribes complex systems with the internal coherence that underlie their persistence over a specific period i.e. a morphogenetic cycle. Metatheoretically, the ICMA is rooted in Bhaskarian Critical Realism and embraces the core maxims of emergence, transcendental realism, and the stratification of social reality; all of which are fundamental to the systemic persistence research problematique (Archer Citation1995; Bhaskar Citation2008). At the heart of the ICMA are three philosophical debates that each exist on their own abstract plains. At the lowest plain is that of structure-agency, which focuses on the respective causal influence of context and conduct on social action. Situated on a higher plain is the material-ideational debate, which respectively concerns the causal influence of natural necessity and anteriority on the one hand, and the expressiveness of meaning and ideational constructs on the other (Knio Citation2018). Finally, the transcendental-immanence debate is located in the highest abstract domain. Transcendentalism is concerned with the conditions that underlie the possibility of something and whether or not another entity is possible. Immanence, meanwhile, asserts that a cause is explicated through an effect in a non-representative and non-resembling expression (Knio Citation2020).

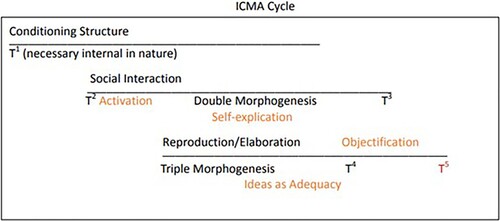

As the name suggests, immanence is at the core of the ICMA framework. It is the Spinozian conception of immanence contained within it that informs the application and diverse conceptual underpinnings of the ICMA (Knio Citation2018). This is the point of departure from which the ICMA markedly differs from Archer’s morphogenetic approach. While both the MA and ICMA are used to provide accounts of the emergence, reproduction, and transformation of social systems, the research process and outcomes entailed in the adoption of either diverge significantly. Archer’s analytical dualism facilitates the analytical separation of material and ideational factors, asserting that social action necessarily postdates social structuring and predates social elaboration in a process which, taken in its totality, comprises a morphogenetic cycle (Archer Citation1995; Citation2020). The conditioning (T1–T2), interaction (T2–T3), and elaboration (T4–T5) phases of an Archerian morphogenetic cycle occur sequentially and intersect with one another (Archer Citation2016). The ICMA shares the same cyclical periodizations as the MA. However, its philosophical juxtaposition through trans-immanence and the implications on its material-ideational engagement means the ICMA supplements MA’s analytical dualism with trans-immanent conceptual framework to scrutinize every level of the morphogenetic cycle. That is, the structure within the whole is transcendentally independent of its effects but also immanently expressed within it. Therefore, there is an unelided unison enabling ontological separation and it is this unison which is abductively explored through the morphogenetic analysis.Footnote1 The contention is that this specific account of trans-immanence in immanent terms necessitates a deeper engagement with the systemic persistence problematique both within and between morphogenetic cycles (Diefenbach Citation2013, 167).

Ideas as self-explication, ideas as adequacy, and systemic persistence

Given the forgoing, it is argued here that the concepts of ideas as self-explication, ideas as adequacy, and systemic persistence enable novel insights furthering research on the themes of inclusive governance and adverse inclusion, neoliberalizing processes in Palestine, and the emergence of AI and Web3. Ideas as self-explication refers to the ways in which ideas, possessive of their own powers, shape the double and triple morphogenesis of agency. The idea explicating itself is of (in)compatibility between the structures at T1 and T2, in other words, the difference (between the structures) that makes a difference (an idea to which corporate agents react in later morphogenetic cycles) (Knio Citation2018; Citation2020) For example, the difference between the good governance agenda at T1 and the inclusive governance agenda at T2 confers an idea of (in)compatibility after T2, for corporate agents, shaping the agency to change institutions of governance itself through T3. Their behavioural reaction prompted by this idea is a re-evaluation of the self and others which leads to what Archer refers to as ‘the double morphogenesis of agency’Footnote2: ‘where agency undergoes transformation, acquiring new emergent powers in the very process of seeking to reproduce and transform structures’ (Archer Citation1995, 190).

By investigating the behaviour of corporate agents as a product of this re-imagining, researchers can analyse whether corporate agents’ behaviour, as explicated by their ideas, shows necessity or contingency relative to the (in)compatibilities at T.Footnote3 As such, this transformation leads to the development of different reflexivities which are the basis of new behaviour and further reactions and thus transformation. It is our contention that the analysis produced by operationalizing the concept of ideas as self-explication explains via the difference between the period of good and inclusive governance, the particular institutional conditions for a shift from good to inclusive governance.

The second concept is ideas as adequacy which occurs as we move closer to T4. This is where actors come to be embedded in corporate agency through the double and triple morphogenesis of agency. In this process, corporate agents (those actors who have come to be embedded in agency), via their interaction through their newly formed reflexivities, have newly emergent dispositional capabilities. These dispositional capabilities enable corporate agents to reflect not only on the synchronic relations that characterized the difference between T1 and T2 but also the diachronic relations that enabled such a difference in the first place. As such, when adequate ideas are at play for corporate agents they can make a transcendental leap as actors in their thinking to understand the immanent cause underlying the internal relations at T1 (Knio Citation2018; Citation2020). It is argued here that this leap provides us with a more nuanced understanding how Palestinian actors were oriented in their actions to intensify neoliberalization processes at T4 in the Palestinian National Development Plans in the years post-2007.

The third concept is that of systemic persistence, which is concerned with those necessary and internal relations that persist through a morphogenetic cycle despite their contingent expression in a variety of forms. For something to be systemic, it must possess properties that ensure its continuity in, through, and over time. These properties are, of course, liable to change via complex process of emergence that results in a new morphogenetic cycle being instantiated. The systemic persistence problematique thus mandates an analytical enquiry to differentiate between a system’s core properties and the emergent forms that are expressions of these properties throughout a morphogenetic cycle. In the section on the IPE of the Internet, the focus is on the relevance of the systemic persistence problematique for ascertaining the parameters of the morphogenetic cycles that are pertinent to project’s goal of constructing an MR account of the IPE of the contemporary Internet. This is done by, first, theoretically elaborating on the movement between T5–T1 that sees the emergence of a new morphogenetic cycle, and the necessity of the systemic persistence problematique for identifying when one cycle ends and another begins. Then, thematic overviews of three core elements of the Internet’s infrastructure – Web2, Web3, and AI – are provided alongside an explication of how systemic persistence is a key foundation of MR’s ability, as a framework, to explore the intricate relations between each of their differing properties to identify the systemic imperatives of continuity and change that traverse the IPE of the contemporary Internet.

Given all of this, the next section of this paper will build upon these theoretical underpinnings to demonstrate the use of ICMA(FR) in three different PhD research projects.

Adversely inclusive governance and ideas as self-explication (Daniel ‘Zach’ Sloman)

Some of the imperatives of inclusive governance are the pervasiveness of social inequality, ecological degradation, and the threats from climate change. For example, the majority of the worlds income goes to the top 10% of earners (Alvaredo et al. Citation2017, 12–14; United Nations Citation2016, 38). Ecosystems have been reduced, commodified, and rendered exclusionary (Hahn et al. Citation2015; Jager Citation2001) and the resultant climate change has created 10 million refugees and counting (Westing Citation1992; Vinyeta, Powys Whyte, and Lynn Citation2015). On one hand, the complexity of these issues has lead scholars to recognize that inclusiveness is not defined clearlyFootnote4 and is instead a normative benchmark for institutions upon which they can be judged (Hickey Citation2015, 1). On the other, the inability to resolve different understandings of inclusiveness across the literature has led to unintended consequences known as adverse inclusion (e.g. Davis Citation2011; Dyer Citation2012; Hickey and du Toit Citation2007). I forge a path forward through this complexity using the ICMA. Specifically, I operationalize the concept of the self-explication of ideas. This is the quality of ideas in which they shape agency itself through the explication of their material circumstances within the behaviour of corporate agents (Knio Citation2018). This is highlighted by my case study on adverse inclusion in New Delhi within which the cultural and structural systems that condition the material context of the idea of social inequality, explicate themselves as ‘inclusiveness’ in policy-makers’ response to inequality. Consequentially, this case study shows how, first, normative claims about inclusiveness obscure and de-politicize its institutional origins; second, the forgoing produces unintended consequences known as adverse inclusion; and third, adverse inclusion itself is the self-explication of the very challenges to good governance, which are not neutral, from which inclusive governance emerged.

Background

The origin of inclusive governance is the good governance agenda (OECD Citation2020, 18) and I take this as the structure at T1. Core to this agenda is that institutions matter, especially for ensuring governance that is fair, accountable, and judicious (Grindle Citation2010). Further, there is a strong reliance on the labour-market as a key institution in ensuring economic growth and social stability. This was the result of a consensus by multi-laterals and (wealthy) national governments and rests on a strong notion of liberal democracy in which the achievement of the aforementioned norms is validated in meritocratic terms. This meant that for the first time, several countries and multi-laterals came together to define what governance is per se and that this was led by specific norms. These norms were to be achieved through the instrumentalization of specific institutions (e.g. Smith Citation2007). Inclusiveness has been added to these norms and is known as ‘inclusive governance’ at T2 (Bossuyt Citation2021, iii; Hickey Citation2015, 1). This means that inclusiveness is one normative dimension of good governance with policy implications but does not change the core logics of good governance as a norms-lead, institutions-first approach (e.g. Weiss Citation2000).

The challenges to good governance: a difference that makes a difference

The norms central to the good governance agenda are increasingly under threat by issues such as climate change, increasing social inequality, and ecological degradation. On one hand, climate change and ecological degradation pose an existential threat to the very existence of institutions themselves, nevertheless the norms they purport to achieve. On the other hand, the systematic deepening of social inequality undermines the notions of fairness and the meritocratic vision of society. Ultimately, these issues are challenges to the liberal-democratic consensus upon which the good governance agenda, its norms, and means, are premised and thus present a contradiction or difference stimulating the change between T1 and T2. As an ex-post recognition, I propose that inclusive governance has emerged as a result of the aforementioned three issues (among others) and as such it is also contemporaneous with them. It follows that corporate agents had responded to this difference – these three issues – in a way that would make the emergence of a new norm of governance possible. In other words, these three issues are the difference that made a difference for corporate agents.

Explicating the difference: the material conditions of incisiveness’ emergence

According to the ICMA, the material conditions between T1 (good governance) and T2 (inclusive governance) are described in terms of Structural Systems (SS) and Cultural Systems (CS). On one hand, they are structures because they are events which are the context of activity (responses in governance) but are not necessarily activity dependent (Archer Citation2020, 138). On the other, disparate events such as an increase in the Pacific Ocean’s temperature or an earthquake in Tokyo to be known as problematic and organized into a thing called ‘climate change’ depends on abstract understandings of their relevance and relations synchronically and diachronically. This means the logics of problematization pre-existing these events, are cultural (Archer Citation2020, 138). These structures and cultures are also systemic in that they are, ‘ … the results of the results of previous interaction in an anterior structural context’ (Archer Citation1995, 188). This means they are not only systematized but emerged as the interaction between systems which already exist. For example, inequality is, on one hand, constituted of the interaction between social, cultural, economic, and political structures which already exist – structural systems. On the other hand, perceiving a homeless man living on a beach in Miami, lined by high-rise apartments as ‘inequality’ is dependent on the interaction of various logics which also already exist – home ownership on the beach as indicating wealth, homelessness indicating a lack thereof, etc – cultural systems.

Finally, that these problems are conceived of as governable is presupposed by a SS and CS. A logic enabling these issues to be seen as governable is the CS while the structural reality of governance informing that logic is the SS. To this point, it goes without saying that logics of governance always include ideas of agents, structures, and of course institutions. My assertion is that for inclusive governance, this is structures as rules, institutions (including the market) as neutral arenas for actors and instruments for (de)incentivizing those actors towards the ends of specific norms, actors with pre-determinable interests, and actors as agents who can use neutral institutions to maximize their utility (Fukuyama Citation2013; OECD Citation2020, 14; Ostrom Citation1990). These are the logics of Rational Choice Institutionalism (RCI) and are evidenced by policies, working-documents, recorded conferences, and research outputs of some of the most prolific multi-laterals in governanceFootnote5 (Burke Citation2011; Ostrom Citation2005a; World Bank Group Citation2018).

The self-explication of ideas

I operationalize the concept of self-explicating ideas to investigate the impact, in terms of the behavioural reactions of corporate agents, to the idea of the challenges to good governance (the difference). This is within the material context of the cultural – logics and structures – happenings as described in the previous section. It follows that the self-explication of ideas means ideas possess agency in terms of,

‘prescribing, shaping, constraining and guiding’ the policy preferences of decision makers […]i.e. their self-explication – which shows how ideas possess agentive capacities that allow them to cause change in policy through their involvement with and explication of the circumstances from which they arise. (Knio Citation2018, 7–9)

The self-explication of RCI in Prakash (Citation2015)

Seeing the self-explication of RCI in Prakash (Citation2015) means first locating interaction at T2: when corporate agents in the Indian government were confronted by the recognition of the difference between good governance at T1 and inclusive governance at T2. In this case, various inequalities challenged good governance and as such, inclusive governance policy and adverse inclusion was the integration of Dalit’s into the labour market to decrease these inequalities (Prakash Citation2015). The Indian government instrumentalized the free-market, ‘to bridge the gap between political equality and severe economic disparities between upper and lower castes’ (Prakash Citation2015, 1044–5). Inclusion, presupposed an impartial market where Dalits could compete for profits (Prakash Citation2015, 1045). Instead, Dalits were subject to socioeconomic domination by upper castes in various ways through their participation. Inclusion that could be adverse is the market as the institution ‘including’, its impartiality as the validation for its inclusiveness, entrepreneurship as the means, Dalits as maximizing the utility of profit accumulation to achieve goals of governance (reduced inequality). Then, adverse was defined in juxtaposition with this ‘inclusion’ (an impartial market), ‘adverse inclusion is said to occur when persons occupying the lower rungs of the social ladder … reap lower returns on their capital investment than their privileged counterparts’ (Prakash Citation2015, 1047).

This shows how, contrary to claims that inclusiveness is only a norm of governance and adverse inclusion is unintended consequences, they are instead created and motivated by specific ontological commitments in ideas about governance. These ontological commitments are the CS in the material conditions of governance. It follows that good governance and the CS enabling problematization conferring ‘political and economic inequality’ is the material conditions (A) while policymakers are corporate agents explicating these material circumstances through the idea of political and economic inequality as a social problem and the inclusive policies that mobilize this problem. I assert that systemic integration for the SS of governance and inequalities in Prakash (Citation2015) are viz-a-viz RCI for corporate agents. The idea of inequality, born of the material circumstances of RCI governance and the logics of social problematization it confers, explicated itself as: a goal of inclusive policy, problematizing this for Dalits, and the instrumentalization of the market as the necessary means to achieve these goals on behalf of Dalit’s (C). This adversely inclusive governance was presupposed by at least 6 necessary conditions (B):

Economic and political inequality as governable

That these are problems

That these are problems reflects the interests of Dalits

That the market is a neutral institution

That the market could be instrumentalized

That these things (1–5) inform the intention of inclusive governance correctly

A was explicated as C but The SS of the context in T2–T3 of New Delhi was not compatible with A. In other words, the logic of RCI which enabled the logics (B) that were the conditions of possibility of inclusion were not compatible with the SS of the context of inclusion (local cultural norms, the caste system, its (dis)embeddedness in institutions) or CS (ways of understanding for people in New Dheli). In this case, inclusion could never have not been adverse. The condition of the possibility of inclusion being adverse is that its logics (B) are taken for granted as part of the intention of governance (6). In so doing, Prakash (Citation2015) and the policymakers obscure the fact that the intentions are not inherently correct. This results in an ‘adverse’ which seems neutral but is in fact only enabled by the transgression of the logics which created inclusiveness in the first place – an explication of RCI to begin with. As a result, the word ‘adverse’ is contaminated by RCI’s self-explication.

On adverse inclusion and self-explication

The forgoing shows that the understanding of actors involved in the aforementioned inclusive governance initiative was one of contingency. I assert this because the policies chosen resulted in an outcome which deepened the challenge of social inequality – contradicting inclusiveness thus creating adverse inclusion. This means that the corporate agents involved may not have had the necessary awareness of the internal relations that makes the difference between good governance and inclusive governance. Generally speaking, if I can observe corporate agents acknowledging inclusive governance as adverse it means that their behaviour from which this is extrapolated can be explicated as containing a necessary understanding of the difference between good and inclusive governance. This is because to say that inclusion is adverse, a juxtaposition from inclusion itself, requires a recognition of the internal relations that make inclusion what it is: inclusion being good and adverse being bad. Therefore, if corporate agents make this acknowledgment, it is necessarily based on an awareness of these internal relations. As such, the concept of adverse inclusion is an exemplar of how the ideas of difference between good governance and inclusive governance (in this case inequality), explicates itself in the behaviour of corporate agents allowing a researcher to interpret their behaviour as necessary or contingent. Taken as part of the entire model, this step (T2–T3) is an example of the necessarily inadequate understanding of institutional change which leads towards adequacy of ideas as exemplified in the next empirical case study.

ICMA-variegated neoliberalization thesis and ideas as adequacy (Yazid Zahda)

Introduction

In this section, I argue that ideas of self-explication and ideas of adequacy provide a nuanced level of analysis as to how neoliberalization processes unfolded in Palestine. I focus on two Palestinian actors: the President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas and former Prime Minister, Salam Fayyad. Both actors in the capacity of their positions facilitated the transition that Palestinian Authority made to the intensification of neoliberalization after 2007. In my research, neoliberalism is conceived of as processes unfolding in time and space. The variegated neoliberalization thesis furnishes the theoretical framework for investigating such processes. However, these processes of the VNLT are treated as tendencies devoid of causal power. In order to account for causation, the research incorporates the VNLT into the ICMA. With ICMA’s precept of ideas as adequacy or ideas as immanent, the research explained how they guided the two actors’ actions towards intensifying neoliberalization in 2007 onwards.

Contextual background

Scholars saw that the Palestinian Authority’s National Development Plans (NDPS) devised in 2007 and onwards paved the way for neoliberalism to take hold in Palestine (Dana Citation2015; Hanieh Citation2013; Khalidi and Samour Citation2011). These plans according to them were aligned with the policy recommendations of the International Financial Institutions. They aimed among other things to prioritize the role of the private sector in development and roll back the government in service delivery. As such, neoliberalism was conceived of as monolithic concept or one-size-fits-all template of policies inspired by the international financial institutions.

This research drawing on the variegated neoliberalization thesis (VNLT) (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010b) approaches neoliberalism as a series of processes unfolding in space and over time. Following that the research explores how neoliberalization processes were actualized in the Palestinian NDPs since the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in 1994. Since the neoliberalization processes are treated as tendencies devoid of causal power, the research incorporates the VNLT into the ICMA. With ICMA’s precept of ideas as self-explication and ideas as adequacy or ideas as immanent, the research explains how Palestinian agents were guided in their actions to mediate and institutionalize the neoliberalization processes.

Theoretical background

Augmenting the VNLT

The VNLT is a theory that transcends dualism in heterodox political economy about neoliberalism as a hybrid, unstable and contextually dependent concept or a hegemonic project with a global mission. It conceives of neoliberalism as a series of processes of neoliberalization unravelling over time and in space (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010b, 182–222). These processes are ‘produced within national, regional, and local contexts defined by the legacies of inherited institutional frameworks, policy regimes, regulatory practices, and political struggles’ (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002, 349–79, 349). The interaction with inherited regulatory structures yields geoinstitutional differentiation or variegation, resulting in an uneven development of neoliberalization. As the neoliberalization processes intensify in vigour through rule regimes, they reconstitute other regulatory structures, i.e. neoliberalization of regulatory uneven development (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010b, 182–222, 209). These processes cannot be ‘represented through crude, stagist transition models’ (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010b, 182–222, 208–9).

As the neoliberalization processes interact with regulatory structures, they facilitate marketization and commodification over three stages. In the first stage of disarticulated neoliberalization, regulatory experiments are put in place with the aim to impose or reproduce pro-market policies of governance, whereby anti-market arrangements are abolished and new strategies are introduced in favour of market discipline. In the second stage of tendential consolidation of neoliberalization, neoliberal prototypes are circulated transnationally to other places. These neoliberal prototypes are presented like all-purpose templates for dealing with context-specific challenges. They take different forms when they are embedded in the new political and institutional contexts. In third stage of intensification of neolliberalization, transnational rule-regimes (large institutions, legal systems and regulatory structures) impose ‘the rules of the game’; these rules become the new parameters of the neoliberalization process (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010a, 327–45, 335–6).

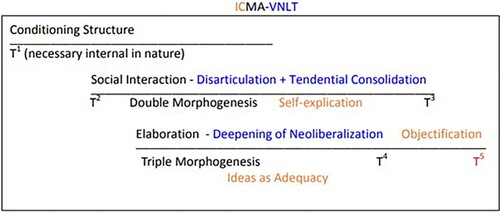

In my research, I adopted this tripartite processual model to examine how the neoliberalization processes unravelled on a local level. However, in order to account for the causal effect of the neoliberalization processes, they need to have properties, instead of tendencies. Moreover, agency, as it stands in the VNLT, is not explicitly teased out and is omnipresent throughout the three stages of the VNLT (Knio Citation2019, 1–14). By incorporating ICMA doctrine of parallelism into the VNLT (See ), I can provide a more nuanced analysis of the unfolding of the neoliberalization processes while accounting for the role of agency in these processes. The doctrine of parallelism with its emergentist analysis of structure and agency allows us to acknowledge the ontological independence of both components. It is, therefore, possible to examine the crucial interplay between these strata (agency and structure) in a dialectical manner. Every structural or cultural system or system integration, which is the outcome of the past interaction, has a property. This property has a dispositional capability, which is the product of synchronic and diachronic processes (Knio Citation2018, 398–415: 4). It follows that commodification and marketization are properties rather than merely processes. So neoliberalization, which according to the VNLT was the outcome of the 1970s Keynesian crisis, was actually rooted way before the crisis hit, since commodification and marketization were part and parcel of capitalism all along. In other words, what the crisis did was to re-invigorate the unexercised powers of those two properties. With that in mind, I can account for the role of ideas as self-explication as agency mediated the first two stages of the VNLT: disarticulation and consolidation of neoliberalization, one the one hand, and the role of ideas as adequacy in guiding actors embedded in agency towards the intensification of neoliberalization, the third stage.

I first unpack the double morphogenesis of agency through the interaction between Palestinian Authority (as the structure) & Oslo Accords (as the culture) with the Palestinian Old Guard & Reformists (as two distinct corporate agencies) at the level of T2–T3. By virtue of ideas as self-explication, I show how corporate agents became self-aware and conscious of their milieu (Knio Citation2020, 489), which guided them in facilitating neoliberalization in the second stage of the VNLT. Afterwards, I engage with the ideas as adequacy through the triple morphogenesis of agency at T3-T4, whereby actors situate themselves in relation to the dominant derivation of the four potential derivations, which are contingent on the situational logics at the level of social interaction. Each derivation sets the dominant mode of reflexivity: communicative, autonomous, meta- or fractured reflexivityFootnote6 at T3 (Archer Citation2012, 16–17) ().

Structure, agency and culture

To start, it is important to define what the nature of structure & culture is at the first level of ICMA cycle. The Palestinian Authority (PA) with its leadership is defined as the structure T1. The PA was created in 1994 as a result of the Middle East Process, which led to the signing of the Oslo Accords (I. Oslo Citation1993; I. I. Oslo Citation1995), a peace agreement, between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), a representative entity of Palestinians, and the Israeli government. The PLO endowed with material resources controlled the newly established PA. The PLO’s Old Guard, who were affiliated to the Palestinian National Liberation Movement alias Fatah, one of the organization’s several political factions, ran the PA’s institutions (Shikaki Citation2002, 89–105). The Oslo Accords are the cultural or ideational structure T1. They defined among other things the nature of relations between the Palestinians and Israelis and the PA’s institutions. These accords also set the corner stone for building the PA’s democratic and efficient institutions. To support, finance and monitor the building of such institutions, international donors, mainly the European Union, the United States and World Bank Group, formed the Aid Coordination Structure. The PA needed to follow their policy recommendations in order to receive international aid. Two corporate agencies stood out as crucial players in the institution building process, the Old Guard (PLO-cum-PA officials endowed with material resources and with vested interests) and the Reformists (some members of the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) of 1996 and members of political factions, including Fatah).

Double morphogenesis of agency (T2–T3) – ideas of self-explication

Disarticulation of neoliberalization

The release of the PLC’s committee’s report in 1998 that laid out the charges of corruption and mismanagement in the Palestinian institutions based on a report by the Head General Control Office enticed some PLC members into voicing their discontent with the bad performance of the PA’s institutions (The Palestinian Council and Jerusalem Media & Communication Center Citation1998). They urged the PA and its then President Yasser Arafat to take concrete action against corruption (Brown Citation2002; Gaess Citation1998, 109–15). This sparked the social interaction at the level of T2 between the Old Guard and those Reformists in the PLC. The Reformists called for democratic and functioning institutions, but to little avail (Brown Citation2002). Their voices, however, found echo among the international community. The corruption charges were later corroborated by the World Bank and the Council on Foreign Affairs in Washington in their reports released late 1990s (Sayigh et al. Citation1999). The Old Guard headed by President Arafat sidelined ignored calls for reforms. He estimated the reforms as a threat to his political power. In an interview with Khalil Shikaki, a Palestinian political scientist, he explained that the international community reached the conclusion that carrying out the reforms without Arafat would be unattainable (Khalil Shikaki, Director of Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), Interviewed by Author, December 27, 2016). While the PA leadership was confronted with the imperative to reform its institutions, neoliberal policies had already been rolled out with the help of the World Bank and international development actors early 1990s (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Citation1999). These policies targeted certain sectors mainly trade relations and some institutions to promote the growth of the private sector.

Consolidation of neoliberalization

The social interaction between the Reformists and the Old Guard continued unabated in the years ahead. That stage of disarticulation was followed by consolidation of neoliberalization between 2000 and 2005. As the PA grew weaker during the Second Intifada with its security infrastructure destroyed by Israeli forces, internal and external calls for reforms gradually gained momentum. A new Palestinian government was formed and set up the 100-Day Reform Plan, backed by the World Bank, IMF and the Quartet (UN, EU, U.S.A., and Russia). The Basic Law was ratified and amended, which brought in drastic changes in the economic and political systems. For instance, Article 21 explicitly stipulating that the Palestinian economy is free market economy. The post of prime minister was created into the political structure of the PA (Palestinian Basic Law Citation2003), which devolved Arafat’s power. Mahmoud Abbas, a PLO-Fatah Old Guard, became the first prime minister of the PA. Following that, Salam Fayyad, a former representative of the World Bank in Palestine, was appointed as the Minister of Finance in 2003. He carried out structural reforms in the PA’s financial management system. He channelled all the PA’s revenues under a Single Treasury Account and downsized the security apparatuses, notoriously corrupt, in addition to reforming the pension system (Innovations for Successful Societies Citation2022a). Aware of the problems that his reforms would create to some people in the PA, his approach was to take on the big problems in small slices so that he would minimize disruptions. He also realized that he had to have a good relationship with Arafat as he wielded influence over the other PA leaders (Innovations for Successful Societies Citation2022b, 5–6).

After the presidential election in 2005, the Palestinians had their second legislative election. This time, the Old Guard lost their control over the PA, but still kept the presidency in their hands. The Islamic Resistance Movement, aka Hamas, won the elections and formed a government that the international community boycotted (Zweiri Citation2006, 675–87). The Old Guard saw the gravity of the situation as the liberal peace & state building, their raison d'être, along with their vested interests and positions was in tatters, especially after Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip in June 2007. The new president of the PA, Mahmoud Abbas, sacked Hamas-led government and invited the reforms advocate Salam Fayyad to form an emergency government in the West Bank (Al Jazeera Citation2007). Fayyad set up a technocratic government of 10 independent ministers and one Fatah-affiliated minister (MIFTAH Citation2013). That decision was a de facto recognition and acceptance of reforms in the PA’s institutions. To sum up, the social interaction Old Guard with the existing liberal ideational structure resulted in the double morphogenesis of these agents, who acted in terms of containment at this level. However, their actions came to translate their self-awareness and consciousness of their milieu. They were aware of the existence of the logic of compromise at the first level. This eventually guided the Old Guard to proceed with the consolidation of the neoliberalization process via the implementation of further reforms.

Ideas as adequacy – triple morphogenesis (T3–T4)

Intensification of neoliberalization

But still the Old Guard was still not aware of ‘what must be there’ for the form (the necessary or contingent internal relations behind the reforms) to exist the way it did. The Old Guard, given the necessary internal relations between the PA and Oslo liberal peace paradigm, distanced themselves from the Hamas-led government, and opted to adhere to the path of Oslo paradigm. By now this Corporate Agency saw the necessary relations of the PA structure were entangled with the aid structure supporting the liberal peace & state building. Acting in accordance with the resultant situational logic of containment as we saw earlier, they became aware of the logic of compromise, i.e. introducing reforms, but they were not yet aware of the necessity behind it.

At this phase, President Abbas ruling over an emergency government, on the one hand, and Fayyad holding two positions as a prime minister and a minister of finance, on the other, they set to re-infuse more liberal reforms. So the disjunction between the structural morphostasis that had not been in favour of reforms and the cultural morphogenesis that advocated reforms engendered a contextual discontinuity, whereby the autonomous mode of reflexivity is dominant in relation to the communicative one, based on the crude ICMA’s four logical derivatives (Knio Citation2018). This type of reflexivity allowed the actors embedded in the Old Guard to orient towards the institutionalization of reforms. So the ideas of adequacy in other words allowed the Palestinian actors to consider the not only the logic of containment but also what laid behind it, i.e. compromise, as the Old Guard came into terms with the Reformists’ calls for reforms in the PA’s institutions. Furthermore, these materially grounded ideas in terms of the PA’s dependency on aid to exist and the liberal peace & state building of the Oslo Accord were systemically persistent. Guided by the situational logic of the compromise, the property of the structural system where cause is not separate from its effect on the actor’s subjective understanding of it, Abbas ushered in the technocratic government to re-invigorate the reforms that were reversed when Hamas was government. Abbas acted knowingly that any Palestinian government that did not embrace the Oslo liberal peace paradigm would face the fate of Hamas, international boycott. Fayyad, on his part, devised a comprehensive neoliberal national development programme, the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP). He sought to ensure that this development programme would stay on the path of Oslo liberal peace. In 2008, he wrote in the Financial Times, ‘[…] the Palestinian Authority remains steadfast in its peaceful pursuit of independence. Central to our approach is the idea that economic development is critical to the success of our state-building project’ (Fayyad Citation2008, my emphasis). With that in mind, the PRDP aimed to boost the economic development through strong engagement of the private sector (Ministry of Planning Citation2008). With the PRDP and subsequent development programmes being institutionalized at T5, Palestinian actors intensified the neoliberalization process.

The unfolding of the neoliberalization processes at the social interaction level and the elaboration level was the result of interplay between the material and ideational at three levels of the MA cycle. The doctrine of parallelism provided a nuanced analysis as to how Palestinian agents made sense of their milieu when they took actions pertaining to consolidating neoliberalization and reflected on the PA’s structure dependent on international aid vis-à-vis the Oslo liberal peace paradigm. The doctrine of parallelism also unravelled how liberal peace ideational structure was grounded in the international aid structure supporting the PA’s existence. The neoliberalization in the NDPs stemmed from the material structure of international aid grounded in the Oslo liberal peace paradigm.

Political economy of the contemporary Internet and systemic persistence (Andrew Dryhurst)

Introduction

The focus of this research project is the nexus between capitalism and the politics of the Internet. Its overall objective is to demonstrate the viability of the MR framework for providing a rigorous mapping of systemic continuity and change within the Internet politics – capitalism nexus across morphogenetic cycles. The project will involve mapping evolutions in the Internet’s infrastructure and architecture and all of the entailed structural and cultural emergent properties (SEP/CEP) and consolidated corporate agencies within a morphogenetic cycle as conceived by Knio (Citation2018; Citation2020). Their specific interplay with different aspects of capitalist accumulation processes and institutional forms (IF) in, through, and across time will be further examined via the ICMA operationalization of FR political economy. However, given that the wider research project is still ongoing, this particular section will focus on one element of the MR framework, the T5–T1 period where new morphogenetic cycles emerge, in order to demonstrate the value of operationalizing the framework to study the Internet – capitalism nexus. The section opens with a brief contextual overview before a theoretical discussion about the relevance of T5–T1 of the ICMA-FR model for establishing the parameters of this given project. The final section ties this together by elaborating upon some of the leading literature and considerations concerning the infrastructure and innovations from herein.

Contextual background

The Internet evidently plays an integral role in IPE. In the contemporary moment, data is a commodity of political and economic import, captured and processed for countless purposes ranging from its use in modelling to assist with the governance of polities and natural resources across the globe, in augmenting global commerce, supply chains, and retail; in scientific research; and for training machine learning systems. Customized and atomized feeds of social media platforms have evolved to become intermediaries into spaces of political understanding and debate; while opaque algorithms are hindering public discussion about discriminatory practices in employment, education, and policing (O'Neil Citation2017); and the construction of 5G critical infrastructure remains an issue of major geopolitical contention (Akcali Gur Citation2022). At the heart of this research project are questions regarding infrastructure and technical innovations that pertain to the loci of power underpinning the politics of the Internet. Infrastructurally, the scope of the project considers evolutions in the Internet from its conception to the nascence of the World Wide Web (WWW), which is here segmented into three components: Web1, Web2, and Web3.

The former is shorthand for the first stage of the WWW’s evolution when it primarily consisted of static pages and users consuming content. Web2 pertains to the interactive web precipitated by a host of innovations in technical standards and protocols that, amongst other things, facilitated the levels of online participation and concomitant data trails that pervade the contemporary moment. As Flew summarizes, the transition from Web1 to Web2 represented a,

move from personal websites to blogs and blog site aggregation, from publishing to participation, from web content as the outcome of large up-front investment to an ongoing and interactive process, and from content management systems to links based on ‘tagging’ website content using keywords. (Flew and Smith Citation2008, 19)

Operationalizing the ICMA-FR

As we have seen, MA is concerned with the emergence, reproduction, and transformation of social systems (Archer Citation1995). What she provides is a framework for giving a historically situated causal account of structural/cultural emergent properties and the powers of structural and cultural systems. Importantly, these causal powers are always mediated through human agency and people, who themselves possess their own emergent powers of social and self-reflection. The ICMA(-FR) inverts the MA’s analytical orientation within the individual reflexivities of actors to provide a framework for studying the interplay of structure and culture with people. That is, to identify that background against which actors reflexively redefine their institutional influences (Knio Citation2018, 13). This very possibility is built on top of the ICMA’s operationalization of Spinozian parallelism and the ontological tangentiality of the material and the ideational of which it is an expression. Whilst the introduction to this paper explained some of the key conceptual innovations of the ICMA, its operationalization in relation to FR requires some explanation. The ICMA provides FR with ontological depth by treating the different institutional forms (IF)Footnote7 within capitalist economies as internal relations of emergent properties. Analytically, this permits analysis of the material and ideational aspects of structure across the stratified domains of a morphogenetic cycle (Knio Citation2020, 23).

Specifically for this section, the MR provides a rubric for understanding how actors embedded in corporate agency navigate their situational contexts to try and cement and institutionalize new necessary relations into subsequent morphogenetic cycles. In an MR analysis, ideas as adequacy reflect an effective understanding on the part of corporate agents of the tangentiality that has persisted between the growth and regulatory regimes. This is a transcendental movement occurring at T4, where agents realize what must have been there throughout the morphogenetic cycle. This realization underpins their subsequent attempts at objectification and institutionalization to try and (re)formulate institutions cemented with new necessary relations. The outcomes of this are conditioned by the Interaction phase, the endometabolism arising out of structural responses to internal systemic tensions, and the hybridization or contingent and endogenous transformation of IFs (Knio Citation2020, 22). At T5, actors embedded in corporate agency try to create institutional coherence before the emergentist modalities of these internal relations are carried through into T1 (Knio Citation2020, 22). That is, they attempt to institutionalize an ensemble of intersubjectivities against persistent objects. The success of this coherence can be tested by whether or not the relations persist through interactions with new social actors into becoming the Conditioning phase of a new morphogenetic cycle.

In terms of the Internet case study, it is evident that the architectural shifts brought about by the rise of ‘Web2’ provided the conditions for large firms to accrue enormous power and influence and, ostensibly, establish themselves as corporate agents within the Internet domain (this will be discussed in greater detail below). The innovations in blockchain and ‘Web3’ cannot be decoupled from this fact, nor can the development of AI systems with its considerable computational and data requirements. However, given the relative recency of developments in Web3, it will be difficult to ascertain whether it represents a new morphogenetic cycle. In fact, the question is raised as to whether the advent of Web2 represents a new morphogenetic cycle and Conditioning phase or is merely just an important immanent transformation in the Internet’s form. That is, were the Web2 innovations in technical standards and architecture indicative of a coherent set of necessary relations between institutions (re)formulated by dominant players? Or of a situation of relative stasis and inertia? To find this out, is it necessary to head back to the early development of the Internet and establish the necessary internal relations between institutions and key players that initially defined the role of the Internet within capitalist economies. Only once this has been done can the systemic imperatives of continuity and change that traverse Web2 and Web3 be identified, and their relative significance be ascertained. By exploring the intricate relations between the properties of these three thematic areas, the project intends to demonstrate the trans-immanent nature of all complex systems. Further, this line of enquiry is compatible with the MR’s emergentist reworking of FR analysis to map the Internet’s historical development in conjunction with the accumulation regimes and regulatory modes of IPE to provide a thorough historical analysis of the Capitalism – Internet nexus.

Politics of Internet infrastructure: Web2 & Web3

It is impossible to discuss the IPE of the Internet without discussing the rise to power of large tech companies whose market dominance and political influence is reified by the network effects that have been accrued through expansive processes of data commodification and extraction. Some accounts have explained this process through the capitalism’s perceived imperative of striving for expansion and accumulation (Srnicek Citation2017), and others through a lens where capitalism endogenously generates its own conditions for change that directly correlate to the new forms of demand, production, and organization entailed therein (Zuboff Citation2019). The unifying thread is that the rise of these firms cannot be decontextualized from those transformations in the material architecture of the Internet that made the monetization of data flows and the economies of scale implicit to the entailed network effects at all possible in the first place. ‘Web2’, ‘identified only by its underlying DNA structure – TCP/IP (the protocol that controls how files are transported across the Internet), HTTP (the protocol that rules the communication between computers on the web), and URLs (a method for identifying files)’ (DiNucci Citation1999, 221), as well as other innovations like dynamic HTML, helped precipitate the participatory Internet that we know today. The underlying architecture of these flows of abundant information facilitated their monetization and a concentration of power arising from the data’s evolution into both a capital good and an organizing architecture (by virtue of the extensive modelling it made possible).

This provides a relevant context for one of the key infrastructural developments of the present moment, where discourses concerning cryptography, privacy, and self-ownership, and the politics of power on the Internet are culturally resurgent. The Web3 movement revolves around the possible computational, political, and economic benefits of replacing intermediary companies and institutions with protocols and ledgers consistently being updated by a distributed network of actors. It is replete with diverse ideologies and perspectives and is focused on decentralizing core parts of Internet infrastructure and processes through cryptography and blockchain/distributed ledger technology (Brekke Citation2019; Nakamoto Citation2008). This debate over (de)centralization speaks directly to issues of infrastructure, concentrations of power, and societal debates about liberties in digital space. It is pertinent to this research project because whilst it ostensibly represents a challenge to the status quo undergirding the contemporary Internet, the fact remains that Web3 is not occurring within a vacuum. To the contrary, it exists in the context of intersecting regulatory, economic, and cultural structures. Aspects of centralization are often times computationally and economically efficient. As the influential cryptographer Moxie Marlinspike explains,

when people talk about blockchains, they talk about distributed trust, leaderless consensus, and all the mechanics of how that works, but often gloss over the reality that clients ultimately can’t participate in those mechanics. All the network diagrams are of servers, the trust model is between servers, everything is about servers. Blockchains are designed to be a network of peers, but not designed such that it’s really possible for your mobile device or your browser to be one of those peers. (Marlinspike Citation2022)

Artificial intelligence

Developments in AI technology and its entailed causal and power relations are also pertinent for understanding the power relations and infrastructure of the contemporary Internet. Historical debates within the field of AI have revolved around the notion of Weak-Strong AI, i.e. that of AI’s operational functionality versus its potential to replicate human intelligence and operate autonomously (Bostrom Citation2013; Turing Citation2007). Conceptually, it is argued that this can be deepened with the addition of a new debate, that of Instrumental-Emergent AI. Traditionally, a large amount of philosophical functionalism has pervaded the AI space (Bryson Citation2019; Searle Citation1984), which has served to underpin an instrumentalist understanding of AI technology in much of the social science literature on the topic. Instrumentalism here refers to AI being understood as a tool and solely in terms of what it does. This is of course necessary at a certain level, given the wide-reaching scope of AI-use cases, the diversity of models and training sets, and the opacity that frequently surrounds AI’s societal deployment (O'Neil Citation2017). Nevertheless, instrumental notions of AI are inescapably presentist in their analytical scope, and it is important to consider that different AI are themselves embedded in an enormous variety of material relations and processes. AI are constructed and deployed by agents who are imbued with their own structural and institutional contexts, interests, ideals, and situational logics. A particular company’s AI systems are necessarily intertwined with the dynamics of (inter)national regulations, supply chains, and (national) accumulation regimes, as well as corporate agents’ reflexive and culturally conditioned actions in and through time. That is, AI are open complex systems embedded in other open complex systems.

Thus, while existing literature on the politics of AI provides thorough accounts on, for example, the material relations of AI supply and value chains (Crawford and Joler Citation2018), the mysticism surrounding its portrayal in public discourse (Campolo and Crawford Citation2020); and the ideological tenets contained within its very conceptualization (Lanier and Weyl Citation2020) – there is a research gap to be filled through tracing AI’s conceptual and material development in relation to the morphogenetically derived systemic imperatives traversing the political economy of the Internet and its history. For example, the ubiquitous deployment of AI models across all aspects of society presupposes questions about attribution concerning the datasets that are fed into different models; the transparency of data collection and processing; and the complex regulatory challenges that widescale AI deployment creates. Similarly, the recursive and emergent consequences of people’s interactions with powerful AI models across industry and society make the models akin to cultural substrates from which particular worldviews may be inscribed and cultivated. To paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, the model may well be the message (Bratton and Agüera y Arcas Citation2022). All of these connote significant economic and social outcomes, and also exemplify a situation where the rise of powerful AI companies, possessive of their own intellectual property, datasets, and modelling practices, ought clearly to be situated within the accumulation imperatives and systemically persistent dynamics shaping the Internet’s development in capitalism because they are intertwined with and shaped by AI’s regulation and deployment as well.

Overall, this project’s research problematique is thus concerned with the extent to which the forms expressed by Web2 and Web3, as well as those surrounding the development of AI, are coherent with a previously instantiated Morphogenetic cycle and the degree to which the necessary relations persisted into a new Conditioning phase. The next stage of this research will involve going back to the initial development of the Internet to try and establish when the T5–T1 occurred within the previous capitalism – Internet politics nexus so as to identify the systemic properties transcending the contemporary Internet.

Conclusion

The first section discussed how research on adverse inclusion suffers from ontological flatness resulting in researchers’ inability to reconcile fundamental differences across the literature. Yet, the imperatives of inclusive governance itself have never been more pressing. In answer to this call, the author contributes by applying the ICMA to adverse inclusion. Through this approach, he argues that inclusion in the context of New Delhi could never have not been adverse because it is the self-explication of Rational Choice Institutionalism. RCI is not compatible with the context of inclusion. This contaminates the concept ‘adverse’; augmenting adversity per se with the requirements of RCI’s subversion. As a result, the concept of adverse inclusion when mobilized by policy makers reproduces inclusion as RCI. Ultimately, he argues against the corpus of literature that makes normative claims about inclusiveness and adverse, and instead asserts that these claims de-politicize and obfuscate the real material and ideational origins of inclusive governance and adverse inclusion.

In the second section, the ICMA allowed for a nuanced investigation of the neoliberalization processes by transcending the VNLT couched in tendential processes of commodification and marketization to their properties. The interaction between the morphostatic structure of the PA (rejecting reforms) and morphogenetic culture of the Oslo peace paradigm (calling for reforms) did not lead, as we have seen, to the protection of the status quo (lack of reforms), but rather to a compromise (introducing reforms). Ideas as self-explication and ideas as adequacy allowed Palestinian agents to contemplate and reflect whereby their actions in mediating the neoliberalization processes were defined in light of the necessary properties of the material-ideational structures of the PA’s international aid and the Oslo liberal peace paradigm.

The third contribution outlined how the ICMA-FR framework is being used to perform a rigorous mapping of systemic continuity and change within the nexus between the politics of the Internet and capitalism across morphogenetic cycles. The T5–T1 phase of the MR was explicated and abstracted in terms of the three core themes of the project Web2, Web3, and AI. The section explained how this invited the researcher to question whether the emergence of the dominant architectural paradigm of the Internet (Web2) did in fact mark the Conditioning phase of a new morphogenetic cycle and demonstrated the importance of heading back to the early development of the Internet in order to establish the necessary internal relations between institutions and key players that initially defined the role of the Internet within capitalist economies. This was deemed necessary in order to identify and ascertain the relative significance of the systemic imperatives of continuity and change that traverse Web2, Web3, and AI as juxtaposed, intersecting, and materially autonomous objects at the core of the modern Internet.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See (Knio Citation2023) within this volume for an elaboration on the concept of calibers to which this refers.

2 ‘“double morphogenesis”, where agency undergoes transformation, acquiring new emergent powers in the very process of seeking to reproduce and transform structures. For in such structural and cultural struggles, consciousness is raised as collectivities are transformed from primary agents into promotive interest groups; social selves are re-constituted as actors personify roles in particular ways to further their self-defined ends; and corporate agency is re-defined as institutional interests promote re-organization and re-articulation of goals in the course of strategic action for their promotion or defence. All the above processes are reinforced or repressed by the overall state of systemic integration, whose incompatibilities foster their actualization and whose coherence serves to contain this transformative potential of agency’ (Archer Citation1995, 190–191).

3 ‘We can observe the results of the double morphogenesis of agency, which usually occurs in the middle of T2-T3, in the four resultant situational logics that Archer proposes to characterize structural and cultural interactions[…]. These situational logics are derived from the juxtaposition of internal necessary relations with external contingency on one hand, and an analysis as to whether such interactions are complementary or incompatible on the other’(Knio Citation2020, 475).

4 The concept of inclusiveness as an institutional norm attempts to bridge the gap that the diversity of issues and outcomes inclusive governance connections covers. Despite this, research indicates various understandings of inclusiveness. Their impacts are divided into six groups here. First, assessing inclusivity is impossible with differing units of analysis (e.g. jobs vs education) (Kruger and Whittaker Citation2015; Ros-Tonen et al. Citation2015; Silver Citation2014). Second, adverse inclusion comes from mismatches between context and governance because of differing methods of including (e.g. redistribution or job-creation) (IMF Citation2017; Gupta and Vegelin Citation2016). Third, there are artificial constraints on policy options due to different causal explanations of governance (e.g. RCI vs Historical Intuitionalism) (Giddens Citation2008; Gupta and Vegelin Citation2016; Ostrom Citation1990; World Bank Group Citation2018). Fourth, exclusion is produced by differing conceptualizations of targets (e.g. focusing on ecology as something separate from humans excludes farmers) (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015; Narayan and Petesch Citation2007). Fifth, different relationships with varying bodies of research, such as exclusion, adverse inclusion, etc. confuse the basis of understanding inclusivity and adversity (Hickey and du Toit Citation2007). Sixth, there are no consistent definitions of adverse inclusion because of 21 different references to adverse inclusion in the literature (e.g. Deshpande Citation2013; Du Toit Citation2008; Fischer Citation2011; Howard Citation2018; Ingram Citation2017; Mcgranahan Citation2016; Prasad Citation2016; Rammelt, Leung, and Gebru Citation2018; Saloojee Citation2011).

5 For example, the World Bank (WB) defines structures and, ‘[i]nstitutions [as] the rules and enforcement mechanisms that govern economic, social and political interactions’ (Islam Citation2018, 2). The United Nations (UN) defines institutions as mechanisms to encourage collective action (Ostrom Citation2005b, 1). For the International Monetary Fund (IMF), structures and institutions are instruments for the management of public resources (‘The IMF and Good Governance’ Citation2017, 1). Finally, the European Union (EU) sees institutions as instruments to achieve goals of governance by influencing the perceptions of citizens such that decisions are legitimized (‘Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)4 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Participation of Citizens in Local Public Life’ Citation2018, 1). Beyond these specific examples this is evidenced by many working papers, policies, conference proceedings, and books among other publications from the UN, WB, IMF, and EU (Burke Citation2011; European Environment Agency Citation2015; Islam Citation2018; Ostrom Citation2005a; Citation2009).

6 Communicative Reflexivity is an internal conversations need to be confirmed and completed by others before leading to action; Autonomous Reflexivity is an internal conversations are self-contained, leading directly to action; Meta-reflexivity is an internal conversations critically evaluate previous inner dialogues and are critical about effective action in society; and Fractured Reflexivity is an internal conversation cannot lead to purposeful courses of action but only intensify personal distress and disorientation (Archer Citation2016, 186).

7 Taken from Knio (Citation2020), the Institutional Forms are: (1) the ‘Nature of the Speed of Technological Change’, (2) the ‘Nature of Demand’, (3) the ‘Nature of Competition’, (4) the ‘Nature of the Monetary Regime’, (5) the ‘Nature of the State-Economy Nexus’ and (6) the ‘Insertion of the State into the World Economy’.

References

- Akcali Gur, B. 2022. “Cybersecurity, European Digital Sovereignty and the 5G Rollout Crisis.” Computer Law & Security Review: The International Journal of Technology Law and Practice 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2022.105736.

- Al Jazeera. 2007. “Abbas Appoints New Palestinian PM.” https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2007/6/15/abbas-appoints-new-palestinian-pm.

- Alvaredo, Facundo, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2017. “World Inequality Report 2018.” Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde 70 (9): 474–477. https://doi.org/10.2143/TVG.70.09.2001601.

- Archer, Margaret. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, Margaret S. 2012. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, Margaret S. 2016. Structure, Culture and Agency: Selected Papers of Margaret Archer. London: Routledge, Taylor et Francis Group.

- Archer, Margaret. 2020. “The Morphogenetic Approach; Critical Realism’s Explanatory Framework Approach.” In Agency and Causal Explanation in Economics, Vol. 5, edited by Peter Róna and László Zsolnai, 137–150. Virtues and Economics. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26114-6_9.

- Bhaskar, R. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. 2nd edn. London: Verso (Radical thinkers, 29).

- Bossuyt, Jean. 2021. Position Paper on Inclusive Governance. Final Report. European Centre for Development Policy Management.

- Bostrom, N. 2013. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boyer, R., J.-P. Durand, and S. H. Mair. 1997. After Fordism (Ser. Macmillan Business). Houndmills: Macmillan Press.

- Boyer, R., and Y. Saillard. 2002. Regulation Theory: The State of the Art. London: Routledge.

- Bratton, B., and B. Agüera y Arcas. 2022. “The Model Is the Message.” www.noemamag.com. https://www.noemamag.com/the-model-is-the-message/.

- Brekke, J. K. 2019. “Disassembling the Trust Machine, Three Cuts on the Political Matter of Blockchain.” Durham University. 1–235.

- Brenner, Neil, Jamie Peck, and Nik Theodore. 2010a. “After Neoliberalization?” Globalizations 7 (3): 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731003669669.

- Brenner, N., J. Peck, and N. Theodore. 2010b. “Variegated Neoliberalization: Geographies, Modalities, Pathways.” Global Networks 10:182–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00277.x.

- Brenner, Neil, and Nik Theodore. 2002. “Cities and the Geographies of ‘Actually Existing Neoliberalism’.” Antipode 34 (3): 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00246.

- Brown, Nathan J. 2002. The Palestinian Reform Agenda. Peaceworks; 48. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace.

- Bryson, J. (2019, January 16) “A Smart Bureaucrat's Guide to AI Regulation.” Joanna Bryson Blogspot. July 1, 2023. joanna-bryson.blogspot.com/2019/01/a-smart-bureaucrats-guide-to-ai.html.

- Burke, Maureen. 2011. “The Master Artisan Maureen Burke Profiles Elinor Ostrom, First Woman to Win the Economics Nobel.” Imf.org. People in Economics (Blog).

- Campolo, A., and K. Crawford. 2020. “Enchanted Determinism: Power Without Responsibility in Artificial Intelligence. Engaging Science.” Technology, and Society 6:1–19. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2020.277.

- Crawford, K., and V. Joler. 2018. “Anatomy of an AI System: The Amazon Echo as an Anatomical Map of Human Labor, Data and Planetary Resources.” https://anatomyof.ai/.

- Dana, T. 2015. “The Structural Transformation of Palestinian Civil Society: Key Paradigm Shifts.” Middle East Critique 24 (2): 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2015.1017968.

- Davis, Peter. 2011. “Social Exclusion and Adverse Incorporation in Rural Bangladesh: Evidence from a Mixed-Methods Study of Poverty Dynamics.” Working Paper.

- Deshpande, Ashwini. 2013. Exclusion and Inclusive Growth. Delhi: United Nations Development Program.

- Diefenbach, K. 2013. "Encountering Althusser." In Althusser with Deleuze: How to Think Spinoza’s Immanent Cause (pp. 165–184). essay, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501301414.ch-011

- DiNucci, D. 1999. “Fragmented Future (Brief Article).” Print 53 (4): 32–32.

- Du Toit, A. 2008. “Adverse Incorporation and Agrarian Policy in South Africa. Or, How Not to Connect the Rural Poor to Growth.” University of the Western Cape. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00086-X.

- Dyer, Caroline. 2012. “Formal Education and Pastoralism in Western India: Inclusion, or Adverse Incorporation?” Compare 42 (2): 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2011.641359.

- European Environment Agency. 2015. “Chapter 7 : Environmental Challenges in a Global Context.”

- Fayyad, Salam. 2008. “Business Can Help Unlock Palestine's Potential.” Financial Times, December 14.

- Fischer, Andrew M. 2011. “Reconceiving Social Exclusion April 2011 BWPI Working Paper 146.” ISS, no. April.