ABSTRACT

This paper addresses concerns that critical realism is a philosophy in search of a method, and that little guidance exists for the application of the philosophy to social research. It advances the idea that the absence of a philosophically embedded method gives critical realists the freedom to choose methods best suited to answering research questions under investigation. The paper utilizes a study into business advisor knowledge transmission, explicating how a sequential world views approach can be used to progressively expand knowledge about the topic. In this context, the research design further illustrates the symbiotic relationship of two different research methods: in-depth interviews & focus groups. The paper does not imply that any method is better than any other, rather adopts the position that methods must always suit the research aim and provide the best approach for answering the research question.

Introduction

As a philosophical archetype for social scientific research critical realism (CR) is gaining popularity (Fletcher Citation2017; Hoddy Citation2019). It provides a robust philosophical underpinning for a variety of social research endeavours (Easton Citation2010; Oliver Citation2012), and is distinct for the analysis of causation (Ton et al. Citation2023). Despite its popularity, concerns remain about the limited availability of methodological guidance for the application of CR (Fletcher Citation2017; Hoddy Citation2019; Hu Citation2018; Ton et al. Citation2023). It is argued that the ‘ … lack of connection to a familiar research methodology may be limiting its application’ (Oliver Citation2012, 371). This ambiguity may be discouraging CR research from progressing beyond philosophical rhetoric, rationalization of retroduction, or the use of mixed methods (Oliver Citation2012). There is an argument by some that CR is hampered because it is a philosophy in search of a method (Yeung Citation1997). To some degree this argument is supported by limited guidance for CR research methods across the broad social science literature (Fletcher Citation2017; Hoddy Citation2019; Oliver Citation2012; Yeung Citation1997). Even though this limitation exists across different social science disciplines, there is a distinct lack of papers which present the application of CR in empirical business research (Frederiksen and Kringelum Citation2021). This paper addresses the paucity of business literature relating to CR research methods by presenting an original CR research design and explaining its application to a specific business research project.

For CR researchers, the purpose of a research method is ‘ … to connect the inner world of ideas to the outer world of observable events’ (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014, 21–22). This enables researchers to look behind the cognitive veils that obscure our understanding of what causes particular events to occur. Considering that these real events often cannot be seen (Ton et al. Citation2023), what is not clear are the rules for how this is achieved (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014). This paper asserts that the absence of philosophically embedded CR methods, such as quantitative methods in positivist research, empowers users of this paradigm to employ a variety of methods suited to both the object of investigation and the purpose (Danermark et al. Citation2002). Freedom to choose the most suitable method enables CR researchers to get the most ‘ … accurate understanding of the world as it really exists’ (Stoecker and Avila Citation2021, 5). Whilst the open-ended choice of method contributes to the concerns about methodological ambiguity, the highly flexible approach of CR enables the method to be selected based on the attributes of what is being studied and what knowledge is being sought (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014; Sayer Citation2000). Unfortunately, CR researchers are considered to be ‘well behind the game’ in developing ‘appealing and accessible material’ connected with CR methodology (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014, 45).

With multifarious methods, CR provides extensive opportunities to publish about diverse research approaches, but there is a need for more options to be explored (McAvoy and Butler Citation2018). There is a slow growing list of published research across the broad social sciences that extol different CR methodological approaches and identify a variety of appropriate methods. Yeung (Citation1997) provides an empirical example of CR applied to human geography, Hoddy (Citation2019) delivers an alternative approach in a social justice-oriented study, Zachariadis, Scott, and Barrett (Citation2013) in information systems, and Fletcher (Citation2017) in a sociological based study. This slowly developing body of work is particularly evident within research domains such as information systems (Henfridsson and Bygstad Citation2013; Njihia and Merali Citation2013), entrepreneurship (Vincent, Wapshott, and Gardiner Citation2014; Wimalasena, Galloway, and Kapasi Citation2021), and health (Cash-Gibson et al. Citation2023). Allen et al. (Citation2013) provides a practical demonstration of using CR and activity theory to explore information systems, Henfridsson and Bygstad (Citation2013) explain configurational thinking using a multi-method research design inclusive of in-depth case studies and case survey methods, and Hu et al. (Citation2020) utilize the DREI(C) method to underpin their empirical research into social entrepreneurship.

Whilst CR methodological guidance is developing in the broader social sciences, there remains limited application of CR methods to business specific research, indicating a significant lacuna exists within this discipline. A few notable exceptions contribute to the emerging CR-based business research. Hu (Citation2018) and Easton (Citation2010) present practical approaches for using CR methods in case study evaluations. McAvoy and Butler (Citation2018, 165) identify a three-step method using causal frameworks and ‘retrodiction applied in cross-case analysis’. Ahmed and Uddin (Citation2018, 2192) use a morphogenetic approach to explore the corporate governance practices of family business groups, analysing a mixture of acquired data, such as: ‘interviews, observations of practices, historical documentation, company reports and research papers’.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the slowly developing list of CR methods literature, presenting a practical application of CR within a business study topic. A real-world business example is provided in this paper by using a qualitative approach to explain how human agency, social structures, and mechanisms, interact to ensure external professional business advisor knowledge transmission events occur. It contributes to shifting CR from being an ambiguous philosophical paradigm underpinning different research approaches, to an embedded philosophy guiding the research design and providing practical methodological approach and methods.

Following this introduction, the paper explains how the CR stratified view of reality is applied to a research project, and then provides a brief introduction to the background of the business advisor knowledge transmission study. The paper then discusses the application of a novel CR research design for the exploration of business advisory knowledge transmission. It progresses to explicating how an expansion of knowledge is acquired through sequential world views. It concludes with the general concept that the pursuit of understanding mechanisms is a never-ending endeavour, and the adoption of multiple world views can help us progressively overcome the cognitive veils that confront us as researchers.

Adopting a stratified view of social reality

As a philosophical paradigm, CR embraces an open view of social reality that resides between the two extremes of positivism and interpretivism. It is founded on the belief that the world exists independently of both human observation and our knowledge of it (Easton Citation2010; Sayer Citation1992). However, CR does not simply distinguish between the world and our experiences of that world: rather it adopts a stratified ontology in which our social and natural worlds comprise of three domains. Those being the ‘actual’ where events occur irrespective of whether we experience them or not; the ‘real’ which incorporates the mechanisms that produce those events; and the ‘empirical’ which represents our experiences of those events and their causal mechanisms (Bhaskar Citation1978; Danermark et al. Citation2002). Bhaskar (Citation1978) asserts that these three domains are distinct because they exist independently of each other. He explains that structures and mechanisms ‘ … are real and distinct from the patterns of events that they generate; just as events are real and distinct from the experiences in which they are apprehended’ (Bhaskar Citation2008, 46).

This study distinguishes the definition of ontology used by Jespersen (Citation2009, 57), who defines ontology as ‘ … the nature of (what exists) in the world’, from the stratified ontology of CR. It could be argued that the empirical domain is an epistemological perspective, and the real and actual domains are ontological perspectives. This stratified CR ontology identifies that both objects and structures ‘ … can be influenced by different mechanisms located in the real domain of reality, causing other different events to occur in the actual domain of reality’ (Phiri and Guven-Uslu Citation2022, 222).

The empirical domain represents human experiences of the actual and the real and is associated with human observation. Thus, existence is not contingent upon whether an object is observable or not. It is possible that events can manifest in the actual domain without being observed, ‘ … or may be understood quite differently by observers’ (Easton Citation2010, 123). Transpiring as a consequence of operational mechanisms in the real domain, causal powers producing actual events can exist without ever being exercised, they retain the unrealized potential of causation. The challenge for researchers is how to explore the generative mechanisms, or causal powers, which tend to produce observable events; this is metaphorically seeing behind cognitive veils. This requires researchers to engage in a process of interpretation, an intervention between the event which occurs in the actual domain and the researchers experience, or observation, within the empirical domain (Easton Citation2010).

Jespersen (Citation2009, 53) provides an explanation of how stratification is used for this intervention when discussing ‘ … the development of a realist-inspired, macro-economic methodology’. An iceberg metaphor is used by Jespersen (Citation2009) to denote that what is observable is like the tip of the iceberg, and the significantly larger unobservable underlying structures lie below the surface. He identifies that our knowledge of reality can be represented by three different strata: the ‘empirical stratum’, the ‘factual stratum’ and the ‘deep stratum’. Using the iceberg metaphor, the ‘empirical stratum’ signifies the surface landscape of the reality we explore and is representative of Bhaskar’s (Citation1978) empirical domain. In the iceberg metaphor, ‘[w]e see just the tip of an iceberg but that doesn’t mean that the invisible three-quarters is not there or is unconnected to what we see’ (Easton Citation2010, 123). Fletcher (Citation2017, 183) identifies the iceberg metaphor as signifying an interconnection between the different stratum and graphically representing the ‘limitations of the epistemic fallacy’. Therefore, we cannot assert that the other stratum below the empirical are unobservable, instead we acknowledge the potential that it may not be observable, or that aspects of what is being investigated may not be apparent. The ‘factual stratum’ is symbolic of the less visible aspects of events and tendencies, where the observation of mechanisms producing actual events is possible to some degree. The ‘deep stratum’ however truly represents the methodological differences associated with CR; it is within this stratum that understanding about the largely unobservable reality can be reached. The development of an enhanced empirical domain of unobservable entities is deduced through evaluating the causal relationships of observable effects (Sayer Citation2000).

This stratification approach enables CR researchers to address the distinction between what actually occurs, what is empirically observed and ‘ … what causes that which occurs and is observed’ (Fleetwood Citation2014, 126). It provides a unique perspective of reality that enables critical realists to construct complex causal narratives about the world under investigation (Blundel Citation2007). The stratification of reality requires social researchers to focus on elements which enable the revelation of generative mechanisms that exist in the deep stratum (Danermark et al. Citation2002).

Causal explanations

When exploring generative mechanisms to answer the fundamental question of ‘ … what caused those events to happen’ (Easton Citation2010, 121), critical realists use causal language founded on two criteria – the notion that ‘real’ causal powers exist, and that ‘actual’ causation is produced by the complex interaction of different entities (Elder-Vass Citation2005). Researchers can explicate how the emergent properties of a unique relationship between entities, and their particular configuration, combine to produce new phenomena (Sayer Citation2000). They can achieve this through indirect methods, such as abduction and retroduction. Abduction being a mode of inference through which critical realists reinterpret and redescribe ‘ … something as something else’ (Danermark et al. Citation2002, 96). This creative process enables researchers to develop an understanding of a concept using a completely different context. Additionally, retroduction is ‘ … a distinctive form of scientific inference’ (Blundel Citation2007, 55) that enables scientific generalizations about underlying structural powers. Retroduction is a method that ‘ … combines the observed regularities (induction) with hypothetical deduction’ (Jespersen Citation2009, 78), and enables a complex narrative about causal mechanisms within the deep stratum to be explained, with aspects of the real world being revealed. Abduction enables the researcher to understand something in a different way using a new conceptual framework, and retroduction facilitates knowledge development of transfactual (theoretical) conditions, structures, and mechanisms that are not directly observable (Danermark et al. Citation2002).

A premise connected to this process of uncovering causal explanations is that as researchers we should not conflate the transitive dimension of our knowledge of the world with the intransitive dimension that consists of the properties of objects, or structures, within the world (Bhaskar Citation1978). An ‘epistemic fallacy’ exists when assertions of being based on our knowledge of being are considered to be true (Bhaskar Citation1998). We seek the truth through our acquisition of knowledge about the world, but we need to appreciate ‘ … what there is and what we can know are two logically independent questions’ (Collier Citation2011, 223). This signifies that ontological truth is not contingent on epistemological views (Collier Citation2011). Changes in our knowledge do not correspondingly infer any transformation to the world itself, and social phenomena exist irrespective of what knowledge we have (Parr Citation2015). This necessitates the adoption of an ontological position of epistemic relativism; meaning that whilst we endeavour to describe the real properties of objects under investigation, our knowledge of those properties is inevitably fallible (Ryan et al. Citation2012).

Epistemic relativism addresses the seemingly dichotomous beliefs of CR, in which the world both exists independent of our knowledge and is also socially constructed. This is because it is possible for ‘[t]he “real” world [to break] through and sometime destroy[s] the complex stories that we create in order to understand and explain the situation we research’ (Easton Citation2010, 120). Thus, it can be inferred that we are never able to truly know our world but rather can describe it with ‘better or worse, truer or less true, accounts’ (Oliver Citation2012, 374). This paper acknowledges that no matter how much knowledge we acquire about the world, we always face another cognitive veil, and the real world continues to largely be unobservable. Importantly this proposition underpinned the development of the research design for the business knowledge transmission project reported on below.

This paper illustrates a multi-layered CR method for examining structures and mechanisms whose causal powers, if enacted, interrelate to cause events to happen. It provides a practical research design through which deeper causal explanations are acquired via a sequential progression of world views. The application of this research design is demonstrated through its application to a study that specifically explores the emergent properties of the knowledge transmission process for professional business advisors, within a Regional Australian context (Labas Citation2019; Labas and Courvisanos Citation2023).

Background to the business advisor knowledge transmission study

The Business Advisor Knowledge Transmission (BAKT) study is a qualitative investigation of the relationship between professional business advisor knowledge and their knowledge transmission actions. Addressing the knowledge requirements of businesses is specifically examined in the context of Regional Australian small businesses. This research was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated Citation2018) (National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, and Universities Australia Citation2018), and the Federation University Australia's Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC).

The study acknowledges the important role that external business advisors play in addressing entrepreneurial and organizational knowledge isolation (Gibb Citation1993; Kent, Dennis, and Tanton Citation2003; Łobacz and Głodek Citation2015) and associated knowledge limitations of small businesses. Organizational knowledge isolation referring to the concept that some businesses, such as small ones, may have limited access to human resources and lack sufficient access to internal knowledge. Such limitations lead to a recognition that learning from another’s experience requires knowledge transmission to occur (Argote and Miron-Spektor Citation2011), that being for knowledge to be conveyed from one individual to another. This research identifies professional business advisors as agents, within the social structure of advisory services, who have causal powers, and whose knowledge stock is the primary mechanism through which these powers are exercised to generate knowledge transmission events between themselves and relatively isolated small businesses.

This study focuses on professional business advisors who service businesses across six Australian regional locations within the State of Victoria, Australia. Over the six regions, a total of 29 face-to-face interviews were conducted, along with one focus group in each region. The interview participants comprised business advisors who were either professional knowledge specialists, professional knowledge generalists, government sponsored agents, or volunteer business advisors. The focus group participants were selected from individuals identified as business experts in each region, some of whom (but not all) provided recommendations of appropriate interview participants.

Researching aspects of the social world, in which both the key actors (business advisors) and business environment (regional economy) continually change, necessitates a research method suited to an open environment (Sayer Citation2000). In the BAKT study this began with adopting a CR philosophy, which influenced the research aim of understanding how external business advisor knowledge interconnect with their advisory actions and the processes of knowledge transmission (Labas Citation2019). The aim being the impetus for the research question: ‘How does the nature of Professional Business Advisor (PBA) knowledge enable or prevent advisor knowledge transmission actions to business, in the context of Regional Australian small business?’ (Labas Citation2019, 5). The objective of the study was to seek causal explanations about the knowledge transmission process, thus influencing the decision to use an intensive, rather than extensive, research method (Danermark et al. Citation2002).

In complex social environments, such as business, the topics of investigation exist within the differentiated reality of open systems. These open systems comprise of a multiplicity of mechanisms and structures (Scott and Bhaskar Citation2015) which have a variety of causal powers. In this environment there is the possibility that an event may be produced from different causes, or where multiple mechanisms may operate together to create an event. In this situation there is a significant risk of causal misattributions (Sayer Citation2000). This necessitates the need for abstraction and an appropriate research design suited to distinguishing such powers. The real-world exploration of knowledge transmission in the BAKT study demonstrates how a qualitative approach using retroductive inferences can provide insights into the deep stratum of this phenomenon. This example also presents a unique intensive research design, that illustrates how a CR approach can be implemented to develop an expanding world view relative to the research question. The next section draws out the expanding world view, and in this way identifies the relationships between causal mechanisms producing business advisor knowledge transmission events.

Expanding knowledge through sequential world views

CR considers business research as operating within open-ended systems, where ‘ … reality consists of different strata with emergent powers, that [have] ontological depth, and [where] facts are theory-laden’ (Danermark et al. Citation2002, 150). Jespersen (Citation2009) addresses these philosophical boundaries through a stratified retroductive approach in which the inter-relationships between three world views are presented.

Jespersen (Citation2009) identifies that a cognitive veil exists between the real world (World 1) and our knowledge of that reality (World 2). Further distinguishing that from an application perspective in which CR seeks to connect what exists in reality (World 1), our knowledge (World 2), and ‘ … practice (World 3) through the acquisition of new knowledge that is constantly confronted with reality’ (Jespersen Citation2009, 84). Considering this, a framework based on multiple world views is suited to research pursuing an epistemological understanding of causal mechanisms. However, the BAKT study found the perceived existence of a terminal point (World 3) as problematic because it represents an epistemological conclusion, the example in Jespersen (Citation2009) being the development of policy advice. It should be noted that Jespersen (Citation2009) does not specifically identify ‘World 3’ as a terminal point, but rather distinguishes ‘World 3’ as the domain in which results are interpreted and applied from the open-system analysis in ‘World 2’. Bhaskar (Citation1978, 147) asserts ‘ … it is only if we begin to see science in terms of moves and are not mesmerized by terminals that we can give an adequate account of science’. Original CR contends ontologically that closure is not possible, that closure represents the artificial construct which enables the capturing of a brief moment in the real world (Banfield and Maisuria Citation2023). It is in this moment that we acquire partial, and fallible, knowledge of that real world. The BAKT study builds a model expressing a sequence of moments in which knowledge of the real world is developed through various world views.

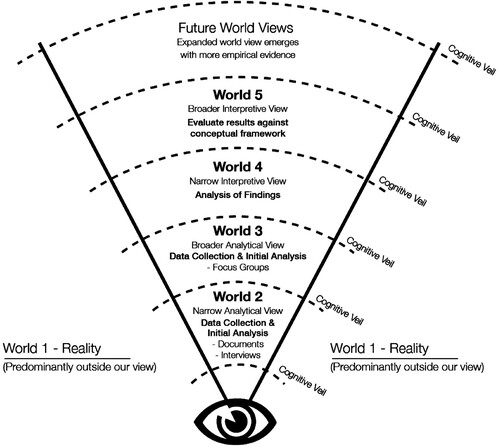

Building upon Jespersen’s (Citation2009) approach, illustrates a research design that addresses the terminal point issue and acknowledges the CR tenet that reality is largely unobservable, and hidden behind a cognitive veil. It starts by acknowledging the largely unobservable deep stratum as ‘World 1’, the predominantly unobservable reality. The research design then proceeds to identify the initial knowledge acquired within a study as ‘World 2’, with the further progressive expansion of knowledge represented as ‘World 3’, ‘World 4’, ‘World 5’ and ‘Future World Views’. The fundamental ontology under investigation, the nature of being, does not change as research progresses through the various world views. However, the research design applied in the BAKT study illustrates that transitioning through world views aligns with progression through the stratified ontology of CR, the study moving from the ‘empirical stratum’ to the ‘factual stratum’, and finally identifying causal mechanisms within the ‘deep stratum’ (Jespersen Citation2009).

The research design applied in the BAKT study () identifies that each time new knowledge is acquired the researcher’s view of reality is broadened. The acquisition of new knowledge enabling a glimpse through the cognitive veil, and a broadening of our world view. However, because of the inherent limitations of human understanding, a new cognitive veil emerges, with the broader reality, ‘World 1’, continuing to remain predominantly unobservable.

World 2 – narrow analytical view

Aligning with Jespersen (Citation2009), ‘World 2’ in the BAKT study embodies the transitive dimension of our knowledge about reality, but is distinct in this approach because it represents an epistemological starting point for the research. Ontologically ‘World 2’ represents the empirical domain in as much that it emerges from the human experience (Bhaskar Citation1978), and represents an empirical stratum comprising of imprecise data (Jespersen Citation2009). It begins with the preliminary characterization of the study from researcher observations of the explored reality and is then filtered through a priori reflection and cursory empirics. It represents a narrow analytical perspective where theory is formulated, conceptual frameworks developed, initial empirical evidence gathered, and preliminary analytical results gained.

For the specific BAKT research project, the development of a ‘World 2’ perspective began with an a priori contention that some individuals providing marketing advice to small businesses do so without appropriate discipline knowledge. This contention was the impetus for examining the relationship between business advisor knowledge and the knowledge transmission processes that influence their advisory actions.

In the BAKT study, abduction is used to reinterpret a range of theoretical concepts and models identified through a literature review, and combine them to create a conceptual framework that incorporates mechanisms involved in knowledge transmission (Labas and Courvisanos Citation2023). The conceptual framework is one element within the research design used to break through the cognitive veil and develop a ‘World 2’ view. An important consideration for achieving this world view is the issue of what theoretical concepts are needed, so as to understand how data can facilitate the comprehension of various mechanisms at work (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014). Whilst certain theories that exist in ‘World 1’ are used in the abduction process, others suitable theories remain hidden behind the cognitive. The abduction process used to create a conceptual framework also contributes to the development of specific interview questions and provides a starting point for thematic codes used in analysis. The developed thematic codes that emerged were clustered into seven categories: (i) PBA characteristics; (ii) Environment characteristics; (iii) Client characteristics; (iv) Relationship qualities; (v) Knowledge transmission opportunities; (vi) Knowledge transmission approaches; (vii) and Knowledge transmission actions.

This foundational knowledge, combined with the research impetus, also provides the basis of the principal research question: How does the nature of Professional Business Advisor (PBA) knowledge enable or prevent advisor knowledge transmission actions to business, in the context of Regional Australian small business? The importance of ideas and concepts for collecting research relevant information underpins the development of a ‘World 2’ view. It emerges from the researcher’s own experiential knowledge, literature reviewed, empirical evidence collected and the interpretation of analytical results.

The initial data collection, and preliminary analysis of documents and semi-structured in-depth interviews, is situated in ‘World 2’. Documents have long been considered as providing valuable supporting data for other data collection methods (Bowen Citation2009), and usually are an easily accessible data source for important descriptive information or historical insights (Merriam Citation1988). In the BAKT study, documents such as marketing material, business websites, LinkedIn profiles and PBA resumes were collected and analysed. This individual documentation was collected prior to conducting in-depth interviews, was used to provide background information about participants, and to help contextualize questions. Documentation also enabled the contextualization of data collected from interviews, and as supplementary data (Bennett and Robson Citation1999).

CR promotes a theory-driven approach to interviewing. It acknowledges the differing expertise of researcher and participant, with the researcher contributing theory-laden subject matter and participant, through their thoughts and actions, adding real world insights into theoretical underpinnings (Smith and Elger Citation2014). The main reasoning for using interviews as a method in the BAKT study is they enabled access to personal viewpoints related to the external knowledge transmission subject. This allowed the researcher to engage in an interactive approach for examining the attitudes of participants and their opinions about experiences, events and activities related to the professional knowledge services they provide (Smith and Elger Citation2014).

As a constructed analytical view, inhibited by the researcher’s human limitations for comprehending empirical findings, the ‘World 2’ view will always be incomplete and differ from the reality of ‘World 1’. ‘World 2’ represents capturing the first brief moment of the real world being investigated (Banfield and Maisuria Citation2023), and symbolizes that moment as being within the empirical stratum. It provides the empirical starting point needed for a retroductive approach to be undertaken. A cognitive veil will always exist between the researcher’s knowledge of the world and the broad actuality of the real world, prompting the continuing expansion of knowledge that enables further glimpses of what is hidden behind such veils.

World 3 – a broader analytical view

Expanding upon the ‘World 2’ viewpoint, the broader analytical view of ‘World3’ represents the augmentation of knowledge through additional data collection, and preliminary analysis of this newly acquired evidence. In the BAKT study this augmentation is achieved using focus groups, a method often paired with the individual interview method. Focus groups providing a way of checking analytical findings and expanding the study (Morgan Citation1996). The inclusion of focus groups in the BAKT study aligns with the contention that triangulation is one method suited to CR (Yeung Citation1997), and provides a second method to explore the emergent themes from interviews in ‘World 2’. Focus groups enable further probing of information acquired from interviews, and the generation of new ideas through dynamic group discussion (Nardi Citation2014). In the BAKT study this includes themes that manifested across all investigated regions and a few themes specific to single locations in the study.

The BAKT research purposively selected a group of regional small business experts to engage in focused discussion about emergent themes within ‘World 2’. These experts were found within local government, local Regional Development Victoria offices, local regional training organizations which provided business mentoring programmes, or regional city council business development departments. Some of these experts had been used initially to help identify interview participants, so had some understanding of the study prior to participating in the focus groups.

A benefit of using focus groups is its participative characteristics which enable members to question each other and explain their own points of view. Specifically, in the BAKT study this was their perceptions about key emergent themes from ‘World 2’. Some of these themes include the importance of government small business programmes, and the identification that these programmes might also produce hurdles for knowledge transference, see Labas and Courvisanos (Citation2021), the value of relationships and networks for the knowledge transmission process, the importance of lived experience for business advisors, the need to understand the characteristics of regional business and the effects of regional isolation, the shift towards online knowledge repositories, and the reactive nature of business advisory services. The collection of this focus group data, and initial analysis, enable the further expansion of knowledge about complex human behaviours and motivations (Brinkmann Citation2012), and the development of a broader analytical ‘World 3’ view.

The emerging ‘World 3’ view represents the continued expansion of knowledge acquired in ‘World 2’. In the BAKT study both ‘World 2’ and ‘World 3’ are ontologically depictive of the empirical stratum. However, ‘World 2’ predominantly uses abductive reasoning to reinterpret theoretical concepts and combine them conceptually, and ‘World 3’ tends to use inductive reasoning. As per induction, the researcher starts with observations obtained in ‘World 2’ and then develops these further in ‘World 3’ by collecting and analysing data, with this analysis leading to the development of theoretical explanations of what was observed (Donley Citation2012). Once a ‘World 3’ view is developed a new cognitive veil emerges with reality continuing to remain predominately outside our view. With the BAKT study, the empirical evidence and analytical results acquired within both ‘World 2’ and ‘World 3’ provided the foundation for the development of the expanded interpretative perspective of ‘World 4’.

World 4 – a narrow interpretive view

Ontologically, ‘World 4’ moves beyond the empirical stratum represented in the analytical perspectives of ‘World 2’ and ‘World 3’, the development of a narrow interpretive ‘World 4’ view is achieved through an in-depth analysis of data from both the interviews (World 2) and the focus groups (World 3). The research design facilitates the development of a ‘World 4’ view through the critical evaluation of acquired data, enabling the researcher to draw inferences that are supported by those data. In the BAKT study, ‘World 4’ uses inductive reasoning to explore what was found in the interviews and focus groups, subsequently drawing conclusions about the events and tendencies that enable business advisor knowledge transmission to occur. Ontologically, ‘World 4’ has moved from the empirical stratum to the factual, with the emergent findings illuminating the agents, structures, and mechanisms that have causal powers.

In the BAKT study, ‘World 4’ identifies three primary influences for business advisor knowledge transmission processes; that being the heterogenous characteristics of business advisors themselves; the characteristics of the environment in which they operate; and the characteristics of their clients. Furthermore, the study identified mechanisms associated with transactional and relational engagements, and three probable knowledge transmission outcomes, namely: guiding, empowering, and producing knowledge.

The ‘World 4’ view represents knowledge acquired from a focused inductive exploration of acquired data. It is a narrow interpretative view because it does not use a retroductive approach to scrutinize the data against theoretical frameworks, but rather explores it for emergent themes. Whilst the definitive answer about reality is not delivered in ‘World 4’, there continues to be an expansion of what is known, and greater depth of knowledge acquired. Because we are never able to truly know our world as further cognitive veils become apparent, and a new world view emerges as the basis of prospective exploration. It is important to understand that the knowledge acquired, and conclusions drawn, in ‘World 4’ is needed for a broader interpretive view to emerge using a retroductive approach.

World 5 – a broader interpretive view

The transition from the factual stratum, of ‘World 4’, to the broader interpretive retroductive view, of ‘World 5’, shows that ideas and concepts are necessary for the deep interpretation of gathered evidence (Ackroyd and Karlsson Citation2014). In the BAKT study, the broader interpretive view of ‘World 5’ illustrates the process of retroduction, in which ‘World 4’ findings are evaluated against the conceptual framework set up in ‘World 2’ and other identified relevant theory. It is in ‘World 5’ that emergent themes from ‘World 4’ are evaluated against theoretical perspectives to develop a deeper understanding of mechanisms affecting business advisor knowledge transmission. The retroductive process enable observed regularities in interpreted data to be combined with hypothetical inductive reasoning for the exploration of largely unobservable social phenomena.

The BAKT study recognizes business advisors as agents operating within the social structure of advisory services. Agents whose knowledge stock is the primary mechanism that enables them to exercise powers for the transmission of knowledge. Significantly the study identifies the causal powers of tacit knowledge as an integral part of the business advisor’s knowledge stock and the primary mechanism in the knowledge transmission process.

‘World 5’ epitomises the methodological differences associated with CR with the revelation of causal mechanisms, power structures, and institutional relations, existing within the largely unobservable deep stratum. In the BAKT study, ‘World 5’ represents the point in which answers for the research question occurred. However, it does not represent the finality of knowledge, again a new cognitive veil exists and opportunities to develop further knowledge arise.

Future world views

Unlike Jespersen (Citation2009), this approach does not identify a terminal point but rather introduces the concept of ‘Future World Views’. The research design illustrates the CR concept of never obtaining absolute understanding, and that finality of knowledge is not achieved because reality continues to remain mainly unobservable. It provides an approach through which expanded knowledge is developed by progressing through sequential world views. Each world view allows the continual broadening of understanding about the reality being studied, without ever achieving a complete picture.

Conclusion: pursuit of knowledge is a never-ending endeavour

Rather than a criticism of Jespersen (Citation2009), this approach pays homage to the multi-world approach developed by Jespersen. The Jespersen model suggests that knowledge acquired is never representative of reality in its entirety, because a cognitive veil will always exist, and knowledge is always limited by the boundaries and context of the study.

The research design, set out in , makes no assertion that by using CR for a particular research project that it should never have a terminal point from which research questions are addressed. Whilst the pursuit of knowledge is a never-ending endeavour, each world view represents both an end point in itself, and a starting point for further knowledge acquisition. It identifies a process in which the research can transition through the ontological strata of CR, from the empirical to the factual, and finally through retroductive reasoning to the deep. It illustrates that to reach the deep stratum might require a range of reasoning be applied at different stages, from abductive reasoning in ‘World 2’, to inductive reasoning in ‘World 3 & 4’ and retroductive reasoning in ‘World 5’. For research in which the objective is policy recommendations, or development outcomes, a world view exit point should exist when sufficient knowledge has been acquired to address research questions, and substantiate any recommendations postulated. In the context of the BAKT study, ‘World 2’ enabled the development of a conference paper presenting a conceptual framework (Labas, Courvisanos, and Henson Citation2015) and a conceptual framework paper (Labas and Courvisanos Citation2023), ‘World 4’ was the basis of a published paper identifying regional policy implications for government funded initiatives aimed at start-up businesses (Labas and Courvisanos Citation2021), and ‘World 5’ underpinned a thesis identifying the significant role that tacit knowledge plays in the knowledge transmission process (Labas Citation2019).

The research design illustrates the symbiotic relationship between different research methods, with each approach building on its predecessor, and the continual development of new world views. It does not distinguish any method as better than any other, rather adopting the position that each method needs to suit the research question and contribute to the expansion of knowledge relative to the research objective. Underpinning the sequential world view approach is the premise that it is futile to engage in a ‘ … one-policy-fits-all approach to research methods’ when researchers have limited understanding about the causal influences of certain mechanisms (Brown and Roberts Citation2014, 306). Instead, this paper presents the view that CR is not ambiguous, either in terms of methodologies or methods. It affirms that CR is unprejudiced, espousing that methodologies and methods should be chosen to address the individual attributes associated with research objectives. In this instance, the BAKT study developed and used a particular research methodology and method for the expansion of knowledge through five sequential world views.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alan Labas

Alan Labas is a management lecturer in the Global Professional School, Federation University Australia, and is a member of the Future Regions Research Centre. Alan’s research focuses on knowledge management with an emphasis on regional business advisory knowledge transmission. Specifically, examining the relationship between professional business advisor knowledge and the knowledge transmission actions undertaken when addressing knowledge requirements of businesses. He has also produced tourism, marketing and event management research. Alan undertakes a practical application of the Critical Realist research paradigm to explain how human agency, social structures, and mechanisms interact in the process of creating knowledge transmission events.

References

- Ackroyd, Stephen, and Jan Ch. Karlsson. 2014. “Critical Realism, Research Techniques, and Research Designs.” In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide, edited by Paul K. Edwards, Joe O’Mahoney, and Steve Vincent, 21–45. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ahmed, Shaila, and Shahzad Uddin. 2018. “Toward a Political Economy of Corporate Governance Change and Stability in Family Business Groups.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (8): 2192–2217. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2017-2833.

- Allen, David K., Andrew Brown, Stan Karanasios, and Alistair Norman. 2013. “How Should Technology-Mediated Organizational Change Be Explained? A Comparison of the Contributions of Critical Realism and Activity Theory.” MIS Quarterly 37 (3): 835–854. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.3.08.

- Argote, Linda, and Ella Miron-Spektor. 2011. “Organizational Learning: From Experience to Knowledge.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1123–1137. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0621.

- Banfield, Grant, and Alpesh Maisuria. 2023. “Introduction: Journeying Through Critical Realism.” In Working with Critical Realism: Stories of Methodological Encounters, edited by Grant Banfield, and Alpesh Maisuria, 1–13. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Bennett, Robert J., and Paul J. Robson. 1999. “The Use of External Business Advice by SMEs in Britain.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 11 (2): 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283245.

- Bhaskar, Roy. 1978. A Realist Theory of Science. NJ: Humanities Press Inc.

- Bhaskar, Roy. 1998. “Philosophy and Scientific Realism.” In Critical Realism: Essential Readings, edited by Margaret Archer, Roy Bhaskar, Tony Lawson, and Alan Norrie, 16–47. London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. New York: Routledge.

- Blundel, Richard. 2007. “Critical Realism: A Suitable Vehicle for Entrepreneurship Research?” In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Entrepreneurship, edited by Helle Neergaard, and John Parm Ulhoi, 49–78. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40.

- Brinkmann, Svend. 2012. Qualitative Inquiry in Everyday Life: Working with Everyday Life Materials. London: SAGE.

- Brown, Andrew, and John Michael Roberts. 2014. “An Appraisal of the Contribution of Critical Realism to Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methodology: Is Dialectics the Way Forward?” In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide, edited by Paul K. Edwards, Joe O’Mahoney, and Steve Vincent, 300–317. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cash-Gibson, Lucinda, Eliana Martinez-Herrera, Astrid Escrig-Pinol, and Joan Benach. 2023. “Why and How Barcelona has Become a Health Inequalities Research Hub? A Realist Explanatory Case Study.” Journal of Critical Realism 22 (1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2022.2095121.

- Collier, Andrew. 2011. “Three Essays Against Nietzsche.” Journal of Critical Realism 10 (2): 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1558/jcr.v10i2.219.

- Danermark, Berth, Mats Ekström, Liselotte Jakobsen, and Jan Ch. Karlsson. 2002. Explaining Society: An Introduction to Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Donley, Amy M. 2012. Research Methods. Edited by Corporation Ebooks. New York: Infobase Publishing.

- Easton, Geoff. 2010. “Critical Realism in Case Study Research.” Industrial Marketing Management 39 (1): 118–128.

- Elder-Vass, Dave. 2005. “Emergence and the Realist Account of Cause.” Journal of Critical Realism 4 (2): 315–338.

- Fleetwood, Steve. 2014. “Critical Realism and Systematic Dialectics: A Reply to Andrew Brown.” Work, Employment and Society 28 (1): 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013501955.

- Fletcher, Amber J. 2017. “Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology Meets Method.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (2): 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401.

- Frederiksen, Dennis J., and Louise B. Kringelum. 2021. “Five Potentials of Critical Realism in Management and Organization Studies.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (1): 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2020.1846153.

- Gibb, Allan A. 1993. “Developing the Role and Capability of the Small Business Adviser.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 5 (2): 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb053550.

- Henfridsson, Ola, and Bendik Bygstad. 2013. “The Generative Mechanisms of Digital Infrastructure Evolution.” MIS Quarterly 37 (3): 907–931. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.3.11.

- Hoddy, Eric T. 2019. “Critical Realism in Empirical Research: Employing Techniques from Grounded Theory Methodology.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 22 (1): 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1503400.

- Hu, Xiaoti. 2018. “Methodological Implications of Critical Realism for Entrepreneurship Research.” Journal of Critical Realism 17 (2): 118–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1454705.

- Hu, Xiaoti, Susan Marlow, Angelika Zimmermann, Lee Martin, and Regina Frank. 2020. “Understanding Opportunities in Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Realist Abstraction.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44 (5): 1032–1056. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719879633.

- Jespersen, Jesper. 2009. Macroeconomic Methodology: A Post-Keynesian Perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Kent, Tony, Charles Dennis, and Sue Tanton. 2003. “An Evaluation of Mentoring for SME Retailers.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 31 (8): 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550310484115.

- Labas, Alan. 2019. The Nature of Professional Small Business Advisor Knowledge and the Knowledge Transmission Process: A Regional Australian Perspective. Ballarat: Federation University Australia.

- Labas, Alan, and Jerry Courvisanos. 2021. “Government Funded Business Programs: Advisory Help or Hindrance?” Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, The 27 (1): 88–112.

- Labas, Alan, and Jerry Courvisanos. 2023. “External Business Knowledge Transmission: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Knowledge Management 27 (8): 2034–2057. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2022-0301.

- Labas, Alan, Jerry Courvisanos, and Sam Henson. 2015. “Business Advisor Knowledge and Knowledge Transference: A Conceptual Framework.” In 28th Annual SEAANZ Conference, 1–17. Melbourne: SEAANZ.

- Łobacz, Katarzyna, and Paweł Głodek. 2015. “Development of Competitive Advantage of Small Innovative Firm – How to Model Business Advice Influence Within the Process?” Procedia Economics and Finance 23: 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00353-6.

- McAvoy, John, and Tom Butler. 2018. “A Critical Realist Method for Applied Business Research.” Journal of Critical Realism 17 (2): 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1455477.

- Merriam, Sharan B. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Morgan, David L. 1996. “Focus Groups.” Annual Review of Sociology 22: 129–152.

- Nardi, Peter M. 2014. Doing Survey Research: A Guide to Quantitative Methods. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

- National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, and Universities Australia. 2018. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Njihia, James Muranga, and Yasmin Merali. 2013. “The Broader Context for ICT4D Projects: A Morphogenetic Analysis.” MIS Quarterly 37 (3): 881–905. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.3.10.

- Oliver, Carolyn. 2012. “Critical Realist Grounded Theory: A New Approach for Social Work Research.” British Journal of Social Work 42 (2): 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr064.

- Parr, Sadie. 2015. “Integrating Critical Realist and Feminist Methodologies: Ethical and Analytical Dilemmas.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (2): 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.868572.

- Phiri, Joseph, and Pinar Guven-Uslu. 2022. “Stratified Ontology, Institutional Pluralism and Performance Monitoring in Zambia’s Health Sector.” Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change 18 (2): 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-06-2020-0081.

- Ryan, Annmarie, Jaana Tähtinen, Markus Vanharanta, and Tuija Mainela. 2012. “Putting Critical Realism to Work in the Study of Business Relationship Processes.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (2): 300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.01.011.

- Sayer, Andrew. 1992. Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach. London: Routledge.

- Sayer, Andrew. 2000. Realism and Social Science. London: SAGE.

- Scott, David, and Roy Bhaskar. 2015. Roy Bhaskar: A Theory of Education. Edited by Roy Bhaskar. Springer.

- Smith, Chris, and Tony Elger. 2014. “Critical Realism and Interviewing Subjects.” In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide, edited by Paul K. Edwards, Joe O’Mahoney, and Steve Vincent, 109–131. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stoecker, Randy, and Elisa Avila. 2021. “From Mixed Methods to Strategic Research Design.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24 (6): 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1799639.

- Ton, Khanh That, J. C. Gaillard, Carole Adamson, Caglar Akgungor, and Ha Thanh Ho. 2023. “A Critical Realist Explanation for the Capabilities of People with Disabilities in Dealing with Disasters.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 26 (3): 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1982629.

- Vincent, Steve, Rob Wapshott, and Jean Gardiner. 2014. “Putting the Agent into Research in Black and Minority Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A New Methodological Proposal.” Journal of Critical Realism 13 (4): 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1179/1476743014Z.00000000038.

- Wimalasena, Lakshman, Laura Galloway, and Isla Kapasi. 2021. “A Critical Realist Exploration of Entrepreneurship as Complex, Reflexive and Myriad.” Journal of Critical Realism 20 (3): 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1935109.

- Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung. 1997. “Critical Realism and Realist Research in Human Geography: A Method or a Philosophy in Search of a Method?” Progress in Human Geography 21 (1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297668207944.

- Zachariadis, Markos, Susan Scott, and Michael Barrett. 2013. “Methodological Implications of Critical Realism for Mixed-Methods Research.” MIS Quarterly 37 (3): 855–879. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.3.09.