ABSTRACT

The Japanese higher education system has struggled with a demographic decline of the university-age population since the 1990s. The expected shrinkage of the overall consumer market due to ageing also significantly pressures Japanese enterprises to expand business in the global market outside Japan. Under these conditions, Japanese universities, heavily reliant on the national language and culture, are facing pressure to internationalise their outlook and operations. However, brain drain is a topic lacking in active discussion, partly because of the continuing inward-oriented preferences of Japanese students, which is aimed towards traditional career mobility within Japanese companies.

Introduction

Japan has begun to experience a significant population decline through ageing. Its population peaked at 128 million in 2008, and has gradually slightly declined since then. In December 2018, the population of non-Japanese citizens remained at 2.7 million, accounting for 2.2% of the total population (126 million) in Japan. In June 2018, non-Japanese, representing only 0.3% of the total population, possessed the residential status of international students. The demographic trends of Japan have been almost entirely determined by internal factors (i.e. fertility and life expectancy) because of its highly limited migratory population (Miyamoto Citation2011). According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (Citation2012), the total population of Japan, including foreign nationals, is estimated to reach 124 million in 2025, and 107 million in 2040.

The Japanese higher education system, which provides highly skilled workers to support the knowledge-based economy, has been considerably influenced by the domestic population change, particularly among the youth. The students of Japanese universities, at least at the undergraduate level, are young and homogeneous. At the same time, only 2.9% of four-year undergraduate students in 2018 were foreign nationals, whereas the share increased to 19.9% of master students and 23.2% of doctoral students (MEXT School Basic Survey).

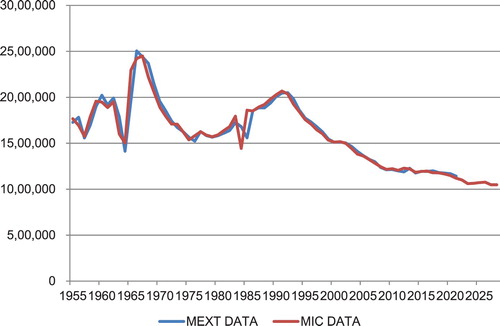

As shown in , based on governmental statistics, the demographic changes among the youth are more drastic and occur earlier than in the total population. The population of 18-year-old youths peaked at the end of the 1960s with the first baby boomers, who were born immediately after World War II. The introduction of the Eugenic Protection Act in 1948, which facilitated access to induced abortions, and the spread of the idea of family planning, triggered the end of the first baby boom (JICA Citation2003). By the beginning of the 1990s, Japan experienced the second peak in the number of 18-year-old youths, signifying the influence of the second-generation baby boomers. The population of 18-year-old youths steadily decreased until around 2010. This age group is predicted to remain stable in the 2010s, but a third-generation baby boom is no longer expected because of the long-term decrease in the birth rate. According to government expectations of demographic trends, a further decline of the youth population is expected sometime after 2020.

Figure 1. Population of 18-year-old youths in Japan (1995–2028). MEXT = Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; MIC = Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. Note: The data from 2012 to 2028 are based on expected numbers. Sources: MEXT and MIC.

After all, Japanese society cannot expect an increase in the youth population from now on unless a significant number of migrants, including international students, are accepted. This scenario raises a key question: What are the consequences of population decline that are relevant to higher education?

The decrease in the youth population itself may be preferable because it expands participation in higher education among domestic students for better career opportunities. Once higher education institutions are established, their capacity to enrol students is not easily decreased, and the higher education system can increase opportunities for high-level skill development towards an age cohort. If the number of higher education graduates decreases, then the number of university-level job seekers decreases as well. However, given the fierce competition in the globalised economy, a decrease in the number of higher education graduates in one country does not automatically ensure less competition in job hunting among the now fewer domestic university graduates.

Thus, we need to consider the following factors in examining the relationship between demographic change, higher education and the national economy. Firstly, the phenomenon of ageing functions as a ‘demographic onus’ (Ogawa, Kondo, and Matsukura Citation2005; Komine and Kabe Citation2009), which is defined as a condition in which the growth rate of the real GDP per capita falls below that of the real GDP per worker (Mason Citation2001). This concept denotes that any decrease in the proportion of working-age individuals in the entire population deprives a country’s economy of productive activity. Having passed the peak of economic prosperity at the beginning of the 1990s, Japan has been experiencing a long-term economic recession known as the ‘lost 20 or 30 years’. This onset of a long-term economic recession coincided with the beginning of the long-term decrease in the youth population starting in the 1990s.

Secondly, the overall increase in the number of competitive higher education graduates at the global level has started to threaten graduates from Japanese universities in terms of job opportunities in both domestic and international contexts. According to the Education Statistics by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, the number of students in tertiary education in Japan slightly decreased from 3,940,756 in 1999 to 3,884,638 in 2012; meanwhile, at the global level, the number significantly increased from 94,572,433 in 1999 to 196,077,086 in 2012. Faced with the shrinkage of the domestic consumer market as well as the high personnel costs in their home country, Japanese enterprises are now shifting their operations outside Japan to seize opportunities for further development. With regard to their human resource policies, these enterprises, particularly in the manufacturing sector, have naturally started to recruit university graduates from other countries, even if this approach has meant decreasing their recruitment of Japanese university graduates (Global Human Resource Development Committee of the Industry-Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development Citation2010).

Thirdly, the competence, knowledge and skills of university graduates are under suspicion in Japan. Historically, the Japanese higher education system has been successful as a screening device for identifying talented human resources with high ‘trainability’, or the capacity to respond to in-house training as part of the traditional model of lifetime employment in large enterprises (Yonezawa and Kosugi Citation2006). However, the decrease in the youth population and the on-going increase in participation in higher education have signified that most universities and colleges have de facto open enrolment. At the same time, the retention rate of Japanese universities remains the highest among the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD Citation2010). In other words, most youngsters in Japan nowadays do not face harsh competition until they graduate from higher education institutions.

Finally, a strong mismatch exists in Japanese university graduates’ readiness to work in a globalised working environment compared with graduates in other countries. The former’s strong orientation towards seeking jobs in large enterprises within Japan has caused Japan’s higher education system to lag behind other industrialised countries in terms of internationalisation. The Japanese government has stressed the importance of fostering a wide range of human resources who can work actively in a global context (Council on Promotion of Human Resource for Globalization Citation2012).

Although higher education is a highly important sector, considering the influence of demographic change on a national economy, research focused on this issue is limited (OECD Citation2008). In particular, the influence of population decline on higher education is a recent phenomenon with which only a limited number of countries have concrete experiences. However, a systemic analysis of recent trends, which considers the long-term perspectives of European and Asia-Pacific countries (including China), is necessary. Japan is recognised as among the first ageing societies along with other advanced East Asian economies, such as Taiwan, Korea and Singapore. Among them, Japan’s case is highly important because it poses a strong barrier of national language in both its education system and labour market (Yonezawa and Kim Citation2008). Facing the pressures of both demographic change and the global economy, the government and higher education institutions are now struggling to strengthen the learning experiences of students to foster globally competitive human resources.

In this article, the author examines the influence of demographic change on higher education using the case of Japan. Firstly, the author reviews the historical process of the systemic transformation of Japanese higher education linked with youth population change and identifies the decrease in youth population as a new challenge by nature. Secondly, the author analyzes the highly complex characteristics of the saturated market conditions of Japanese higher education through publicly available data. Thirdly, the author explores the other important factors that impose pressure, such as the structural change in the global economy, particularly the rise of economic power among Asian neighbours, and how this factor has pushed Japanese higher education towards internationalisation. Fourthly, the author introduces the current efforts of the Japanese government and universities for further transformation towards internationalisation. Finally, the author proposes regional-level collaboration for tackling the combined effects of demographic change and globalisation.

Historical process for meeting demographic change

Historically, the Japanese higher education system centred on the challenge of meeting excess demand until the end of the 1980s. Since the establishment of a modern higher education system in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the government could never provide sufficient learning opportunities in the public sector. The number of learning opportunities at national public universities, at least at the undergraduate level, has always been restricted, based on financial limitations and the policies of a government reluctant to downgrade the quality of national higher education to maximise student enrolment (Amano Citation1996). Municipal governments established local public universities to meet the local needs for human resource development and the demand for higher education, particularly among local students. However, the majority of these universities and colleges have remained small and incapable of absorbing the entire demand for university education.

Similar to South Korea and many other Asian countries, private institutions have absorbed the demand for higher education in Japan (Umakoshi Citation2004). The quality of private institutions is quite diverse, although relatively strict national quality assurance systems, combined with a partial public subsidy to private universities and schools, have certainly worked to ensure the minimum standards of quality in educational services. At one point, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, the Japanese government introduced strict control measures for student enrolment among private universities and colleges. However, after a tentative increase in higher education enrolment brought about by the second-generation baby boomers in the latter half of the 1980s, the government relaxed its enrolment policies (Yonezawa Citation2010). Amano (Citation1996) pointed out that at the beginning of the 1990s, the direction of policy shifted from higher education planning to one of allowing the market to function as a control mechanism.

The reduced control over higher education enrolment immediately decreased enrolment among less prestigious sectors in higher and postsecondary education. Since 1976, non-university institutions called ‘special training colleges’ have provided vocationally oriented postsecondary programmes (Amano Citation1996). According to the School Basic Survey by MEXT, the number of newly enrolled students in special training colleges decreased from 364,687 in 1992 to 264,255 in 2014. Junior colleges, which have primarily functioned as short-term higher education programmes offering associate degrees for female students, also experienced a reduction in new enrolees, dropping from 254,953 in 1992 to 61,699 in 2012. By contrast, the enrolment of new students in bachelor’s degree programmes at universities and colleges continued to increase from 541,604 in 1992 to 619,119 in 2010, and then started to decrease to 608,247 in 2014. This increase in enrolment at the bachelor level until 2010 occurred because the government encouraged the transformation of junior colleges into four-year universities to meet the shift in demand among female students, who went from wanting only a junior college education to seeking a full university education. However, even bachelor programmes are also dealing with saturation or even shrinkage of the market.

Saturation of the higher education market and its consequences

What is the condition of a saturated higher education market? In Japan, a surplus among less prestigious bachelor’s degree programmes became apparent beginning in 2000 (Taki Citation2000). The percentage of four-year private universities that have faced shortfalls in student enrolment compared to the quota authorised by the government increased from 3.8% in 1996 to 27.8% in 2000 and then to 45.8% in 2014 (Promotion of Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan Citation2014). Since the mid-2000s, the closure and the suspension of new enrolment among less prestigious private universities have occurred frequently because of the shortage of students, whereas the new universities have been established every year to seek a new student market. In 2012, the government formed a special committee to reconsider the process of authorising the establishment of new universities, reflecting a sense of market saturation crisis in higher education revealed by Makiko Tanaka, the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology appointed by the government led by the Democratic Party Japan at the time.

Meanwhile, the completion (retention) rate of universities and colleges remained at 89% in 2008, the highest among the member countries of OECD (OECD Citation2010). This figure indicates that admission into and graduating from some universities and colleges are easy in Japan. In the last 20 years, the Japanese government has promoted various university reforms to enhance student engagement in scholarship and to ensure positive learning outcomes. However, recent survey results demonstrate that the average number of study hours, including private studies, among students in Japanese universities – even at top universities – is lower than that of U.S. university students (Central Council for Education Citation2012).

In general, prestigious universities, such as the University of Tokyo and Nagoya University, remain highly successful in job placement for their graduates. However, graduates from less prestigious universities and colleges tend to face difficulties in obtaining regular full-time jobs. At the same time, the idea of ‘lifetime employment’ has proven, for more than 20 years, to be a myth for the majority of university graduates. The Japanese Prime Minister together with his Cabinet (Kantei) set up the Dialogue on Employment Strategy in 2011, during which they pointed out that 52% of higher education graduates in 2010 had been unsuccessful in achieving a stable working status as regular workers by 2012. Overall, the decrease in youth population is not necessarily linked to an increase in job opportunities, as expected by Easterlin (Citation1987).

Increasing pressure of the global economy

By the end of the 1980s, Japanese society and its government had already recognised the new pressures created by the changing global economy. However, a series of policies and practices for the internationalisation of Japanese higher education over two or three decades have not caught up with the rapid change in the global economy.

The economic boom throughout the 1980s triggered a shortage of human resources; subsequently, the labour costs among those who had accomplished schooling in Japan significantly increased. This phenomenon was disadvantageous for the manufacturing sector, which had supported the country’s rapid economic development. Japanese industries started to move their assembly and repair factories first into neighbouring Asian countries and later across the world. By the mid-1990s, Japan began to experience a temporary oversupply of university graduates with the second baby-boom generation, combined with the effect of economic recession after the overheated economy (Kariya and Honda Citation2010).

However, by the time, Japanese society had already started to prepare for the future decrease in the youth population and the upcoming ageing society. The internationalisation process started with the acceptance of youth with international profiles. In 1983, the Prime Minister at the time, Yasuhiro Nakasone, launched a plan to accept 100,000 international students by the end of the twentieth century, which was realised in 2003 (Yonezawa Citation2011). Universities, colleges and other educational institutions also provided preferential treatment to ‘returnee’ children who had been educated outside of the Japanese education system and faced admission difficulties through the regular entrance examinations in the Japanese language (Goodman Citation1993). At the same time, the government and most large enterprises actively sent their executive staff members to study abroad with financial support. Some individuals, particularly young women, also studied abroad, seeking better careers. At the time, most of these individuals returned to Japan, in contrast to the case of other Asians, such as Koreans and Chinese, who generally sought opportunities to migrate.

The pressures of the global economy intensified after the New Industrial Economies, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong, established their status as economic leaders by the end of the 1990s. Some member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), such as Malaysia and Thailand, also experienced an economic take-off by the mid-1990s. After the beginning of the twenty-first century, both China and India began to attract global attention as strong industrial economies and potentially huge consumer markets.

To distinguish Japan from other Asian competitors, the Japanese government and industries strengthened their investments in science and technology (S&T). After entering the long-term economic recession at the beginning of the 1990s, the Japanese government increased public investment in S&T, which improved the financial condition of top national research universities to some degree (Yonezawa Citation2007).

Japanese manufacturing industries also shifted their emphasis to high-technology products and made financial investments in the manufacturing sector overseas. However, the preferences of the students and the workforce favoured the service sector, not the ‘dirty and dangerous’ manufacturing sector. The share of the labour force that worked in the service sector had already reached 63% in 2000, thus transforming Japan into a service economy (METI Citation2001).

Some service industries, such as convenience and department stores, gained the status of international brands (Takeuchi and Shibata Citation2006). However, Japan has been unsuccessful in exporting service products and in attaining the status of a global financial hub. Certainly, South Korea, Taiwan and China have caught up with Japan in the production of electronic devices and other manufacturing industries. Moreover, their capacity for effective global marketing tends to be stronger than that of Japan. Considering the shrinking labour force and the reduced consumer market due to ageing, the globalisation of most Japanese enterprises is inevitable (Global Human Resource Development Committee of the Industry–Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development Citation2010). Since its alliance with Renault in 1999, Nissan has already made English its official working language, and other cutting-edge enterprises, such as Rakuten and Uniqlo, have followed suit (Tokunaga and Momii Citation2011). The recruitment of Japanese engineers who have attained high levels of knowledge, skills and experience in Japanese enterprises is becoming commonplace for Asian enterprises (Nikkei Citation2012).

Current challenges for further transformation

These rapid changes in the economic environment, which affect managers and workers in Japanese industries, undoubtedly require a fundamental transformation of Japanese higher education.

The government and Japanese universities are now attempting to re-establish their leading status in Asia and in the world. Attracting international students, particularly from neighbouring Asian countries, has again become a more urgent task on the policy agenda. In 2008, the government issued a plan to invite 300,000 international students by the end of 2020. The government also provided various project funds to strengthen the international profiles of university management and education. Under the project, ‘Strategic Fund for Establishing International Headquarters in Universities’, from 2005 to 2009, the government selected 20 leading universities and research institutes to receive support for strategic capacity building to internationalise their operations. Under the Global 30 Scheme, beginning in 2009, the government subsequently selected 13 leading comprehensive universities to serve as models for strengthening global competitiveness in the learning environment. These universities were encouraged to recruit international students and faculty and to provide degree programmes in the English language at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. In addition to these schemes, the government has provided various types of project funds to encourage students and academics to work actively in the international community by the 2010s.

Compared with the experiences of Asian neighbours, such as China, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong (Altbach and Balán Citation2007; Altbach and Salmi Citation2011), the influence of these governmental initiatives has been much more modest, partly because of the status that had already been established among top Japanese universities and partly because of greater financial stringency on the part of the government. In reality, in terms of net cross-border student mobility within the last decade, Mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan have transformed themselves from ‘sending countries’ into ‘receiving countries’. If we include short-term language programmes, China has already far exceeded Japan in terms of the acceptance of international students.

Thus, Japan can no longer lay claim to a distinctive economic and educational attractiveness in Asia, although it remains one of the leading economies (Yonezawa and Meerman Citation2012). The competition for luring talented students has intensified among Asian universities and around the globe. Faced with difficulties in attracting the number of talented international students that they had in the past, opinion leaders in the academic and the industrial world argued that Japan’s younger generation needed to increase its global competitiveness.

The concern that younger Japanese people are more inward-looking, at least compared with those of the country’s Asian neighbours, became widespread around 2010. In general, Asian youths are strongly oriented towards pursuing learning and employment opportunities across borders (Kitamura and Sugimura Citation2012). Although brain drain from these countries remains serious, some countries such as China and South Korea have started to call back these lost talents. However, Japanese youths were already attracted to domestic learning and employment by the end of 1980s. Although studying and working abroad are commonplace, many youngsters still tend to maintain a strong link with the Japanese education system and local enterprises. This inward-looking attitude may be reflected in Japanese students’ unpreparedness in studying abroad for their international career development. Japan’s national average score in the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), a widely used English-language test for applicants to universities in the United States and other countries, is 70, which is surprisingly low compared with those of other leading economies in Asia (Singapore, 98; India, 91; Korea, 85; Hong Kong, 83; Taiwan, 79; and China, 77) (Educational Testing Service Citation2013). According to the Open Doors Data of the Institute of International Education, the number of Japanese students in degree programmes at U.S. universities is small compared with other Asian economies, both at the undergraduate level in 2013 (Japan, 9155; China, 110,550; Korea, 36,992; India, 12,677; Taiwan, 5886; Hong Kong, 5830; and ||Singapore, 2285) and graduate level (Japan, 3562; China, 115,727; India, 61,058; Korea, 18,894; Taiwan, 10,117; ||Singapore, 1519; and Hong Kong, 998). The strong reliance on the national economy and language, and the recent modest internal competition among members of the younger generation, are regarded as the factors most responsible for the weak performance in English-language communication. At the same time, Japanese university students view their families’ decreasing ability to afford financial investments and the more intense, protracted job search before graduation as obstacles to studying abroad (Yonezawa Citation2014).

Among international students, the more talented ones with strong expertise or language proficiency in both Japanese and English are warmly welcomed by Japanese enterprises. However, the most recent international graduates from Japanese universities do not gain any advantages in Japan or in their home countries, except in enterprises related to the Japanese industry (Moriya Citation2011).

The sense of crisis among Japanese enterprises has intensified, particularly because they face a shortage of globally active leaders. Globalised enterprises, such as SONY and Olympus, started to hire non-Japanese chief executive officers. At present, no Japanese business schools are included in the world rankings listed by the Financial Times. In 2010, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), in collaboration with MEXT, issued a plan to foster the development of ‘global human resources’ (Global Human Resource Development Committee of the Industry–Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development Citation2010), which referred to those who possess communication skills in an internationally used language (e.g. English), intercultural competency and leadership, in addition to the basic skills necessary for businesspersons. This concept together with the supporting policy agenda have been further assessed by MEXT and Cabinet governmental committees, industrial associations and university consortiums.

Aside from inviting 300,000 international students to enrol in Japanese institutions, the government also set the official target to send 120,000 Japanese students abroad by 2020. Moreover, the government has begun to support strategic mutual student exchange programmes with China, South Korea (CAMPUS Asia), United States, ASEAN countries, Russia and India. The argument for developing ‘global human resources’ originally targeted rather elite students. However, this concept is currently being applied to a significantly more diverse group of students (Yonezawa Citation2014).

In January 2013, the Abe Cabinet established the Education Rebuilding Council immediately after the Liberal Democratic Party regained the ruling status. The council comprehensively discussed the formulation of a new national vision of educational policies and highlighted demographic change as an important factor. In addition to the internationalisation efforts, the council report stressed the importance of diversity, lifelong learning and a security net for career development, which are more evident in welfare state policies. The government started new programs to support internationalisation of leading universities titled Top Global University Scheme in 2013, and then, started to select top national universities as Designated National Universities for further reforms from 2017. At the same time, MEXT started to consider the regulatory limitation of the student numbers at the metropolitan city areas to secure the student market for the universities located in small cities or in rural areas.

Conclusion

Demographic changes, particularly the decrease in the youth population, have comprehensively influenced the higher education system in Japan, combined with the increasing pressure for globalisation. This issue should be examined in a global context; that is, in the context of Japan’s relationships with emerging economies, which, in numerous cases, are benefitting from a ‘demographic bonus’, in contrast to the ‘demographic onus’ phenomenon that is underway in Japan.

Firstly, the ageing of the population has slowed down economic development, particularly in the manufacturing sector, which requires a large, cheap labour force. These factors have stimulated local enterprises to become global enterprises in their search for opportunities for further development.

Secondly, the decrease in the size of the youth population reduces competition among the youngsters as they are being screened for the domestic education system. Youngsters tend not to engage seriously in competition-oriented learning unless they realise how fierce the competition is at the global level. The gap between domestic and global-level competition seems to be most serious in middle-sized countries such as Japan, in which almost all of the students speak the same language. Youths in countries with huge, diverse populations, such as China and India, inevitably face fierce domestic competition. By contrast, youths in countries with a smaller population, such as Singapore, Malaysia and South Korea, take global competition for granted.

Therefore, the governments and industries of countries such as Japan should formulate purposeful policies and implement actions to internationalise their higher education systems. In Japan, internationalisation efforts began with policy actions aimed to bring international talent into the Japanese system. However, this effort gradually shifted towards fostering globally competitive human resources through its own education system and by sending domestic students abroad.

The risk of brain drain in Japan lacks active discussion. An ageing society is unattractive to members of the younger generation due to several factors. Firstly, further economic development cannot be expected. Secondly, members of the younger generation have to support the increasingly ageing population. Finally, the pensions of the younger generation are not secure in the current system. Furuichi (Citation2011) has described this condition as ‘happy youth in a hopeless country’. Evidence that the Japanese youth will continue to prefer to stay in Japan if they succeed in acquiring globally competitive work skills is lacking. In fact, the phenomenon of middle-aged engineers working across the border for non-Japanese enterprises is commonplace. At the same time, many Japanese companies are willing to operate globally and invite global talent for top management positions.

Discussion among Japanese opinion leaders on how to address possible brain drain issues is lacking. Interestingly, the current on-going debate on educational policy under the initiative of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe apparently emphasises policy visions that used to be viewed more as a welfare state.

A potential solution to this problem could be a regional collaboration with the country’s Asia-Pacific neighbours. Japan could enhance its attractiveness as a member of the prosperous Asia-Pacific region. Nevertheless, a strong consensus in the regional arena regarding education is wanting, whereas de facto economic interdependence is apparent. The Asia-Pacific region is highly diverse compared with Europe or Latin America, for example. However, the demographic issue is already a common challenge among leading economies in East Asia, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and China. On-going efforts should be undertaken at the regional level to address the issues induced by demographic changes among Asian countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Altbach, P. G., and J. Balán. 2007. World Class Worldwide: Transforming Research Universities in Asia and Latin America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Altbach, P. G., and J. Salmi. 2011. The Road to Academic Excellence: The Making of World-Class Research Universities. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Amano, I. 1996. “Structural Changes in Japan’s Higher Education System: From a Planning to a Market Model.” Higher Education 34 (2): 125–139.

- Central Council for Education. 2012. Aratana Mirai wo Kizuku tameno Daigaku Kyoiku no Shitsuteki Tenkan ni mukete [Quality Transformation of University Education for Constructing a New Future]. Tokyo: MEXT.

- Council on Promotion of Human Resource for Globalization. 2012. An Interim Report of the Council on Promotion of Human Resource for Globalization Development. Tokyo: Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet.

- Easterlin, R. A. 1987. Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal Welfare. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ETS (Educational Testing Service). 2013. Test and Score Data Summary for TOEFL iBT Tests. Princeton: Educational Testing Service.

- Furuichi, N. 2011. Zetsubo no Kuni no Kofuku na Wakamono tachi [Happy Youth in a Hopeless Country]. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- Global Human Resource Development Committee of the Industry-Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development. 2010. Develop Global Human Resources Through Industry–Academia–Government Collaboration. Tokyo: METI.

- Goodman, R. 1993. Japan’s ‘International Youth’: The Emergence of a New Class of Schoolchildren. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency). 2003. Second Study on International Cooperation for Population and Development New Insights from the Japanese Experience. Tokyo: JICA.

- Kariya, T., and Y. Honda. 2010. Daisotsu Shushoku no Shakaigaku [The Sociology of Transition from University to Work]. Tokyo: The University of Tokyo Press.

- Kitamura, Y., and M. Sugimura. 2012. Hendo suru Asia no Daigaku Kaikaku [University Reform in Changing Asia]. Tokyo: Gyosei.

- Komine, T., and S. Kabe. 2009. “Long-Term Forecast of the Demographic Transition in Japan and Asia.” Asian Economic Policy Review 4 (1): 19–38.

- Mason, A. 2001. Population Change and Economic Development in East Asia. Challenges Met, and Opportunities Seized. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). 2001. White Paper on International Economy and Trade 2001. Tokyo: METI.

- Miyamoto, M. 2011. Jinko Gensho Jidai no Lifestyle [Lifestyle in a Society of Population Decrease]. Chiba: The Open University of Japan Press.

- Moriya, T. 2011. Nihon no Gaikokujin Ryugakusei Rodosha to Koyo Mondai [Foreign Students and Workers and Their Employment]. Kyoto: Koyo Shobo.

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 2012. Population Projections for Japan: 2011–2060. Tokyo: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

- Nikkei. 2012. “Electronics Brain Drain Bolstering Asian Rivals.” Nikkei, July 30.

- OECD. 2010. Education at a Glance 2010. Paris: OECD.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Corporation and Development). 2008. Vol. 1 of Higher Education to 2030. Paris: OECD.

- Ogawa, N., M. Kondo, and R. Matsukura. 2005. “Japan’s Transition from the Demographic Bonus to Demographic Onus.” Asian Population Studies 1 (2): 207–226.

- Promotion of Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan. 2014. Shiritsu Daigaku Tanki Daigaku tou Nyugaku Shigan Doko [Trends of Application for the Enrollment for Private Universities and Junior Colleges]. Tokyo: Promotion of Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan.

- Takeuchi, H., and T. Shibata. 2006. Vol. 2 of Japan: Moving Toward a More Advanced Knowledge Economy. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

- Taki, N. 2000. “2000 nen no nyugaku jokyo no sokatsu [University Entrance in 2000].” IDE 421: 61–66.

- Tokunaga, T., and K. Momii. 2011. Global Jinzai Ikusei no tameno Daigaku Hyoka Shihyo [Indicators for University Evaluation Aiming at Global Human Resource Development]. Tokyo: Kyodo Shuppan Press.

- Umakoshi, T. 2004. “Private Higher Education in Asia: Transitions and Development.” In Asian Universities: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges, edited by G. A. Philip, and T. Umakoshi, 33–49. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Yonezawa, A. 2007. “Japanese Flagship Universities at a Crossroads.” Higher Education 54 (4): 483–499.

- Yonezawa, A. 2010. Realizing Mass Higher Education and the Management of Private Universities in Japan. Sendai: Tohoku University Press.

- Yonezawa, A. 2011. “The Internationalization of Japanese Higher Education. Policy Debates and Realities.” In Higher Education in the Asia-Pacific: Strategic Responses to Globalization, edited by S. Marginson, S. Kaur, and E. Sawir, 329–342. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Yonezawa, A. 2014. “Japan’s Challenge of Fostering ‘Global Human Resources’: Policy Debates and Practices.” Japan Labor Review 11 (2): 37–52.

- Yonezawa, A., and T. Kim. 2008. “The Future of Higher Education in the Context of a Shrinking Student Population: Policy Challenges for Japan and Korea.” In Vol. 1 of Higher Education to 2030, edited by OECD, 199–220. Paris: OECD.

- Yonezawa, A., and R. Kosugi. 2006. “Education, Training, and Human Resources. Meeting Skill Requirements.” In Vol. 1 of Japan: Moving Toward a More Advanced Knowledge Economy, edited by T. Shibata, 105–126. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

- Yonezawa, A., and A. Meerman. 2012. “Multilateral Initiatives in the East Asian Arena and the Challenges for Japanese Higher Education.” Asian Education and Development Studies 1 (1): 57–66.