ABSTRACT

This study uses the Aristotelian notion of phronesis as a critical lens for examining how global citizenship education is prefigured in the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence. Based on a content analysis of key curriculum documentation, the findings outline the way in which techne and episteme with their associated ways of knowing and acting dominate the curriculum. Nevertheless, the hints of phronesis indicate the potential for developing a more critical form of global citizenship education that prefigures praxis that wisely pursues that which is good for humankind and individual flourishing. This article contributes to the notion of ‘planetary phronesis’ as a critical concept for the further development of global citizenship education.

This study uses Aristotle’s notion of phronesis as a critical lens for reappraising the need for and challenges of global citizenship education (GCE) and examines how GCE is prefigured in the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (CfE). Global citizenship is not a legal status but rather an understanding of our position in the world as an ethical responsibility towards oneself, others and the environment. GCE should encourage students to develop an awareness of the global context as well as the rights and responsibilities that are needed to respond to challenges that arise due to globalisation (Canton and Garcia Citation2018) and to move beyond cognitive knowledge and skills to find ways to resolve potential or existing global issues that menace our planet. Moreover, as societies are fluid and susceptible to change, interconnected and interdependent, GCE should enable students to recognise this interconnectedness, the inevitability of change and that individual actions and principles contribute to social justice, sustainability and peace across the globe (UNESCO Citation2019, 8). As a multidisciplinary arena GCE is relevant to all levels and contexts of education, and should be critical, opening spaces for criticism and access to alternative perspectives (McSharry Citation2016).

This study explores how GCE is prefigured in the Scottish CfE. The new millennium in Scotland welcomed two major reforms, the reinstatement of the Scottish Parliament and the formation of Scottish Education and curriculum. Scotland aimed to improve and invest in education, while considering the ‘developing technologies and future demands and patterns in the global context’ (Bryce et al. Citation2018, 900). Since 2004, the CfE has been subjected to ongoing reformations to keep up with the demands of globalisation, social, economic and technological preparing children, and young adults in Scotland with the skills and competencies to succeed in the workforce.

At the heart of Scottish Education, the four capacities reflect and recognise the lifelong nature of education and learning. These capacities are to promote Successful learners, Confident individuals, Responsible citizens and Effective contributors (Scottish Executive Citation2004, 11). Critics, however, point out that although the CfE is progressive, it remains technical-instrumental (Muller and Young Citation2010; Priestley and Sinnema Citation2013). Moreover, policymakers and teachers need to obtain a critical approach to tackle global trends (Bryce et al. Citation2018). The formal written curriculum is particularly significant as an authoritative starting point for the development of the intended and enacted curriculum (Bergqvist and Bergqvist Citation2017), although in addition to the written documentation (printed pages), the intentions and enactment of teachers can significantly mediate the final form of the curriculum. Whether teachers, however, can adopt a critical approach is arguably prefigured by the curriculum as it is the curriculum that should guide and promote the intellectual, personal, social and physical development of pupils, as well as the way in which learning is planned and experienced.

If GCE is to strengthen ethical responsibility towards oneself, others and the environment the way in which GCE is prefigured in the curriculum is important. GCE can be implemented as an additional subject or a cross-curricular notion infused with educational values (Bamber Citation2020). Even with GCE widely accepted as the way forward for a better future and common good, its introduction into curricula raises questions. The first question regards the kind of GCE that is prefigured, and, therefore implemented in educational settings, along with the ideological constellations that envisage the different types of GCE (Pashby et al. Citation2020). The second question regards the nature and the discursive orientations of the curriculum, in other words, who is in control of what is taught and learned. Finally, how the concrete immediacy of local aspirations and national citizenship can relate to the distant, abstract global (Goren and Yemini Citation2017), and, whether GCE promotes homogeneity by putting aside local cultural, political, social, economic and environmental issues, and favouring a unified and universal approach that fails to address social injustices and challenge neoliberal agendas (Stein Citation2017).

As the Scottish CfE continues at the heart of educational reform in Scottish Education, with ongoing revisions and changes, this document is comprehensive and specific, and is designed to exert control over what is taught and achieved. The focus of this study is on what kind of GCE is prefigured in the written documentation of the CfE.

Theoretical framework: global citizenship education as a form of praxis?

Historically, the world has faced serious challenges that jeopardised stability, violated human rights and undermined social justice and democracy. Today we continue to experience dramatic encounters, which threaten the planet and humanity itself, engender self-destruction and ‘dehumanisation’ (Freire Citation2017, 17). Pandemics, climate change, racism, economic inequality, poverty and abrupt immigration are only some of the issues that have recently disrupted societies and the environment, while raising concerns that regard democracy, sustainability and peace. These issues impact life at local, national and global levels. Geographical borders do not make us immune to any of these problems, as humanity is interconnected and interrelated in so many ways (Salter and Halbert Citation2017).

The current significance of GCE is emphasised in the understanding of global citizenship as the bond of our common humanity, an ‘ethos’ obtained through education that promotes active contributions to create a more just, peaceful, tolerant, inclusive, secure and sustainable world (Fernekes Citation2016, 35). According to UNESCO, GCE aims ‘to support learners to revisit assumptions, worldviews and power relations in mainstream discourses and consider people/groups that are systematically underrepresented/marginalised’ (Toukan Citation2018, 58)and ‘refers to a sense of belonging to a broader community and common interconnectedness between the local, the national and the global’ (UNESCO Citation2015, 17).

Critical analysis of GCE highlights three different ways of understanding global citizenship: as a qualification emphasising the acquisition of skills, knowledge and competences for participation in the global market economy (Mannion et al. Citation2011); as socialisation associated with economics, human capital theory and neoliberal ideologies whilst also bringing together human rights, peace education and education for sustainable development; and as a stance that critiques post-colonialist approaches and casts a critical eye over GCE itself. GCE has been criticised, however, for lacking a philosophical and theoretical grounding that enables the unleashing of its transformative potential (McSharry Citation2016). This unclear grounding is exacerbated by the conflation of ‘ideological adaptations situated within the wide umbrella of liberalism’ (Pashby et al. Citation2020, 152).

This third critical disposition of taking a stance aligns most closely with the notion of educational praxis as it aims for emancipation from systems and structures maintaining subordination and oppression, processes circulating and reproducing inequalities, and violations of human rights and environmental responsibilities. Critiques of GCE, however, claim that it often functions as a preparation for modernity enforcing a unified system originating from a postcolonial era linked to neoliberal world views and interests (Mansouri, Johns, and Marotta Citation2017, 4). Moreover, GCE has been critiqued for requiring people to develop competencies within an increasingly competitive context with emphasis on instrumentalism and individual and national development that prioritise global market-driven performance and interventions over local aspirations (Mansouri, Johns, and Marotta Citation2017). Educators have also struggled to scrutinise power relations and systems, and to facilitate open discussions on uncomfortable matters and contradict western vs southern, local vs global interests, as well as retaining approaches that are under-theorised and inadequate to address issues of equity and justice (Shultz Citation2018).

Three types of knowledge

Using Aristotle’s different forms of knowledge to approach GCE, however, could help educators develop a more critical stance towards GCE. In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle outlines three types of knowledge with associated actions. As a form of knowledge, episteme adheres to universal and eternal truth, maintaining a positivist ontology with the associated action of theoria emphasising the objective of theoretical knowledge. In contrast, techne focuses on production associated with poiesis, a technical sense of making things (Mahon, Heikkinen, and Huttunen Citation2018). Knowledge as phronesis, however, pursues a prosperous life together with others and is accompanied by praxis, ‘action based on judgement about what is wise and right in everyday dilemmas and situations’ (Mahon, Heikkinen, and Huttunen Citation2018, 15).

Praxis can be understood in two ways, as an action that is morally committed and informed by traditions in a field and as ‘history-making’ educational action. The first case aims for the good of those involved and for the good of humankind, whereas the second case is concerned with the moral, social and political consequences. These two cases provide different orientations to the notion of praxis, one as action within the present, the other on the action as a precursor for the future. From a praxis-based perspective, education can be defined as

the process by which children, young people and adults are initiated into forms of understanding, modes of action, and ways of relating to one another and the world, that foster (respectively) individual and collective self-expression, individual and collective self-development and individual and collective self-determination, and that are, in these senses, oriented towards the good for each person and the good for humankind. (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, 27)

Andreotti’s (Mannion et al. Citation2014) critical work on GCE distinguishes between soft and critical forms of global citizenship that offer people the space needed to reflect on immediate contexts, as well as on their own and other’s epistemological and ontological assumptions. Critical global citizenship promotes awareness of unequal relationships managed by elites that reproduce ‘ethnocentric and developmentalist mythologies on the less developed countries that seek to help and develop’ (Mannion et al. Citation2014, 144). GCE can also be more critical by shifting the metaphors from the notion of global belonging to planetary citizenship, a planet that we inhabit ‘on loan’ (Spivak, 1999 as cited in Andreotti Citation2011). These critiques highlight the problematic lack of clarity regarding the founding definition of GCE and the risk of GCE regenerating or adhering to notions that initially it aimed to overcome such as inequalities and myths of cultural supremacy.

This study aims to examine how the Scottish CfE prefigures GCE and to ascertain whether GCE promoted in the CfE fosters critical, lateral thinking and reflexivity that strengthen GCE as a praxis-based form of education or a form of education based on episteme and techne. Using Aristotle’s theory of knowledge to explore how the three nodal points of citizenship, sustainability and the global dimension intertwine within the CfE, our research question is ‘How is GCE prefigured in the CfE?’ The following section outlines the methodological approach of the study.

Methodology

Data collection

The data consists of key documents that constitute the Scottish CfE. The curriculum comprises a series of different that encompass advice, guidance, and policy for different curriculum areas. These documents are published online to help teachers, practitioners and other stakeholders retrieve information, appropriate guidance, support and policy. presents the different documents and their respective purposes.

Table 1. 1 Content of the CfE documents.

Compiling the dataset

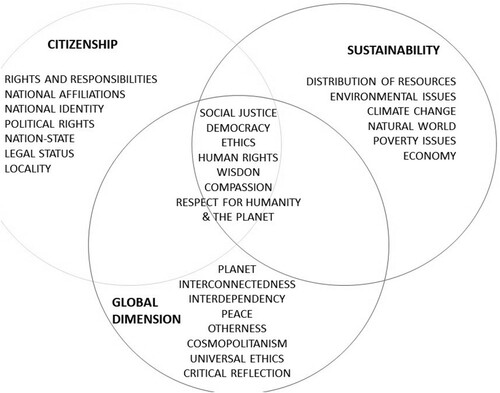

As the aim of the study is to examine what kind of GCE is prefigured in the Scottish CfE the dataset includes the CfE documents that address citizenship, sustainability and the global dimension. These three concepts can be considered as the critical ‘nodal points’ (Mannion et al. Citation2014, 4) that represent the political, environmental and interconnected character of GCE. presents the key concepts that were used to identify extracts pertaining to citizenship, sustainability and the global dimension in the CfE as well as the interconnectedness of the nodal points.

Figure 1. Key concepts connected with citizenship, sustainability and the global dimension in the CfE.

The documents and reasons for selection are outlined in . As the ‘Building the Curriculum’ includes five documents, these were also read and selected based on their relevance to the study.

Table 2. Documents included in the compiled dataset.

Analysing the dataset

The content analysis of the dataset focused on how the nodal points are present and intertwined in the CfE. Once the dataset was compiled, the first step was to create a table to collate the key extracts from the different documents and to colour code the extracts to indicate whether they referred to citizenship, sustainability and/or the global dimension (see ).

Table 3. Extract from the dataset illustrating the colour coding and explication of the themes within the text.

As the nodal points were traced through the documents, the ways in which these notions converge and diverge helped to map the way the form of GCE in the CfE. The final analytical stage critically considered whether GCE was prefigured as techne, episteme, or phronesis.

Findings

The findings outline how the three key themes of GCE are present in the CfE documentation in the early documentation (2004–2006), in the ‘middle years’ documentation (2008–2011) and in the recent Refreshed Narrative (2019).

Citizenship in the foundational documents

Both a Curriculum for Excellence, 2004 and Building the Curriculum 1, 2006 refer explicitly and implicitly to citizenship. Citizenship is a national priority for education along with Achievement and Attainment; Framework for Learning; Inclusion and Equality; Values and Citizenship; and Learning for Life’. The above ideals can be linked to phronesis, however, lack of clarity or elaboration regarding their meaning and application within education means that these ideals are reduced to instrumental goals. Moreover, the emphasis placed on developing an educational system to ensure all children and young people in Scotland achieve successful outcomes and are equipped to effectively contribute to the Scottish economy and society, now and in the future (Scottish Executive Citation2004, 6) suggests a techne-based citizenship. As such, citizenship is framed in economic terms and other contributions to society remain vague. ‘Successful outcomes’, and ‘to equip’ reveal an objective-driven curriculum, which aims to prepare citizens to be able to operate successfully in the market economy.

In these early documents, knowledge is a commodity with outcomes that need to meet specific needs in addition to references to social justice, as well as personal and collective responsibility. These values were developed to reflect Scottish democracy, based on the inscription of the Parliamentary mace (Scottish Executive Citation2004, 11), even though they carry the strong meaning they are only mentioned twice in the 70 pages in total and it is the only time social justice, along with collective and personal responsibility is mentioned. Hence, even if phronesis is touched in the text, the emphasis and focus form a technical curriculum.

The early documents also refer to the need to reflect on social issues in Scotland, such as the growing diversity, need for improved health and reduced poverty. Although these important aspects for the prosperity of a society are included, the absence of discussion on what it would mean to deal with issues of poverty, or the increased diversity limits the value of these references. Similarly, the Scottish values ‘wisdom, justice compassion and integrity’ (Scottish Executive Citation2006, 11) lack specification or elaboration on what is wisdom and what it means to be wise. In these words, there is an element of a citizenship that recognises social justice as vital to democracy and the welfare of a nation, understanding that social problems can be the responsibility of all as well as of the individual, but fails to move forward and acknowledge injustice, political responsibility and a critical stance of why and how there is poverty. These social issues are also intertwined with a competitive environment and that this growing diversity can be the result of economic, social and political consequences. In the same texts, again in the form of listed words, there is a short reference to the importance of children understanding diverse cultures and beliefs and developing concern, tolerance, care and respect for others and themselves. To achieve these values the curriculum should, according to the ‘A Curriculum for Excellence, 2004’, enhance the rights and responsibilities of individuals and nations, develop concern, tolerance, care and respect for oneself and others, make valuable contributions to society and widen the children’s experiences of the world, while fostering informed and responsible citizenship. At first glance, it is presumed that phronesis is hidden in these words, however, a closer examination suggests a tendency towards an individualistic sense that involves a reciprocal obligation between the individual and the community leaving out any political responsibilities and implications.

Sustainability in the beginning

The theme of sustainability intricately connects with citizenship and the global dimension through its regard for social justice, reduction of poverty and human rights at local and global levels. Sustainability, however, also involves issues of climate change, distribution of resources and awareness of systems of inequality. Although there is no direct reference to sustainability in the early documentation there are references that can reveal what type of knowledge is promoted. The five National Priorities are anchored with the concept of sustainability, as well as with the concept of citizenship, which reveal a situated character of sustainability that is value-based and thus promoting a type of knowledge that is technical, rather than wise or prudent. Further analysis of the early documents suggests that sustainability and citizenship foster a practical approach that focuses on active learning and community interaction, thus sustainability begins to veer towards active engagement in environmental projects and community services within a local and national context, where political dimensions seem to be obscure and vague. Episteme and techne are, therefore, prevailing as the children develop a community-based or school-based knowledge with a practical sense, ignoring issues of phronesis and a critical approach to matters such as injustice and poverty.

A global beginning?

The global dimension encompasses principles of social justice, diversity, democracy, equity-based on a critical awareness of global power asymmetries and emancipation. The early documentation focuses on national priorities and values that aim to reflect ideals that pertain to the Scottish context, ‘what we value as a nation and what we seek for our young people’ (Scottish Executive Citation2004, 9). Although these ideals seem to relate to phronesis, the urge to apply them beyond the boundaries of the local sphere is absent and it is also problematic that the promoted ideals are fostered within the local context and lack clarity. Furthermore, the way the values and national priorities are presented (in a list of words) reveal a rather technical-instrumental approach, which is intertwined with techne.

GCE in the early documents

Based on the analysis, GCE in the early documents appears to be techne-based, although it has the potential to incorporate episteme, if greater attention is given to the contributions of scientific knowledge and to even benefit from the critical insights offered by phronesis, if ethical matters are discussed, along with critical reflection.

Middle years

The ‘Building the Curriculum’ documents are designed to provide support for developing the broader areas of the curriculum. In these documents, there is a discernible tendency to refer to skill development, as well as attributes and knowledge as providing opportunities for all children in Scotland to flourish through an increased economic growth. The aim of the CfE is to prepare all young people to find their position in a modern society and economy. It is notable that ‘Building the Curriculum, 4’ solely focuses on skills, with the term mentioned more than 500 times, whereas justice, democracy or global are barely mentioned. In this series, skills are related to competencies and the ability of the individual to carry out tasks with a practical sense, deriving from training and/or experience, while being able to apply theoretical knowledge. Skills also involve behaviours and attributes that make individuals more effective in education and training, employment and social engagement. Emphasising skills in this way indicates a practical approach to education with its purposes realised through material-economic outcomes and utilization suggesting a techne-based form of knowledge with a hint of episteme.

Sustainability in the middle years

Emphasis on the development of ‘skills for learning, skills for life and skills for work’ that children will need as members of a modern society and that will allow them to flourish and contribute to the economy are also important for the preservation and maintenance of sustainability. However, the lack of attention to equity, justice and wisdom, underlines the technical approach reinforced by measuring success in terms of economic performance. Phronesis is absent from these documents, in other words, no attention is given to how skills and knowledge contribute to the benefit of humankind beyond the immediate demands of the economy. Arguably this gap could be filled through interdisciplinary and active learning addressing themes such as citizenship and learning for sustainability, yet the minimal attention given to these possibilities in the guiding documentation of the curriculum suggests that rather than foster a deeper approach to accumulating relevant knowledge, enabling phronesis, interdisciplinary and active learning could be used to foster generic learning experiences that are apolitical and individualistic.

The global dimension

The global aspect has already been mentioned in the early documents as part of the four capacities, the global dimension is mainly referred to in areas such as the arts, language, religious and moral education, sciences, social studies and technology. These references, however, do not compare with the emphasis given to the acquisition of skills in the focus areas of literacy, numeracy or health and wellbeing, nor is time allocated for each curriculum area specified. As such the global dimension lacks consistency and depth, running the risk of being conceived as a theme embedded across the curriculum and used to develop the acquisition of generic skills rather than a feature of disciplinary knowledge, case in point; ‘Important themes such as enterprise, citizenship, sustainable development, international education and creativity need to be developed in a range of contexts’ (The Scottish Government Citation2008, 23). Thus, even if there is a hint of phronesis, techne seems to prevail.

Refreshed narrative

The most recent document in the CfE series is the ‘Refreshed Narrative, 2019’. In this document, the four capacities continue to be at the heart of education in Scotland and the key concepts of GCE are more explicitly present than in earlier documentation. For example, a ‘responsible citizen’ should:

show respect to others, commitment to participate responsibly in political, economic, social and cultural life, able to develop knowledge and develop knowledge and understanding of the world and Scotland’s place in it; understand different beliefs and cultures; make informed choices and decisions; evaluate environmental, scientific, and technological issues; develop informed, ethical views of complex issues (Education Scotland Citation2019).

In the further analysis of the form and presentation of the four capacities, however, citizenship is reaffirmed as an individualistic approach with an emphasis on activity and community. Moreover, it is the social aspect of citizenship that is attended to within the curriculum rather than the political domain which questions the relationship between the state and the citizens, the kind of democracy prevailing and collective responsibility. Although a practical sense of citizenship seems to prevail, wise individualistic choices are fostered as the ‘Refreshed Narrative’ includes links and references that may promote learning for sustainability and creativity. The Learning for Sustainability document also encompasses global citizenship although as it addresses issues of social justice it follows the earlier pattern of being confined to activity and the community. While this document suggests that schools should model the kind of society that should be encouraged, it is not further specified, as such this phronesis turn remains vague.

Sustainability and the global dimension intertwined in the Refreshed Narrative

All four capacities revisited in the ‘Refreshed Narrative’ include statements that relate to sustainability and the global dimension. As the Refreshed Narrative restates the four capacities aim for:

Successful Learners [that] … think creatively and independently; make reasoned evaluations; link and apply different kinds of learning in new situations. Confident Individuals with … physical, mental and emotional wellbeing; secure values and beliefs and able to; relate to others and manage themselves; develop and communicate their own beliefs and view of the world; assess risk and take informed decisions; achieve success in different areas of activity.

Responsible Citizens [able to] … respect for others; commitment to participate responsibly in political, economic, social and cultural life and able to; develop knowledge and understanding of the world and Scotland’s place in it; understand different beliefs and cultures; make informed choices and decisions; evaluate environmental, scientific and technological issues; develop informed, ethical views of complex issues.

Effective Contributors … make informed choices and decisions; work in partnership and in teams; apply critical thinking in new contexts; create and develop; solve problems.

recognises the knowledge, skills and attributes that children and young people need to acquire to thrive in out interconnected, digital and rapidly changing world, and enable children and young people to be democratic citizens and active shapers of the world.

To sum up, the four capacities appear to be deal with words that are interwoven with phronesis, yet, the fact that they are presented as capacities unveils a techne-based approach that aims to determine how the individual should be and thus associated with neoliberal tendencies with specific outcomes.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore how GCE is prefigured in the Scottish CfE. Although GCE is not an explicit goal of the CfE, the stated aim of establishing wisdom, justice, compassion and integrity as the foundation for the curriculum, as well as the four capacities and national priorities align with the basic tenets of GCE. Using Aristotle’s three types of knowledge as a lens for analysing key curriculum documents provides critical sensitivity to the form of GCE prefigured by the curriculum and potentially enacted by teachers. Whereas techne is inherently demonstrative and episteme comprises scientific knowledge, phronesis seeks to grasp the nature of prudence, in other words, phronesis is inextricably intertwined with wisdom, so that individuals are able to deliberate rightly, not only about oneself, but what is conducive to the good for humankind and life in general (Taylor Citation2012). Using Aristotle’s theory of knowledge to explore how the three nodal points of citizenship, sustainability and the global dimension intertwine within the CfE, the findings from this study outline how and what type of GCE prefigured in the CfE, as well as the way in which the prefiguring of GCE has developed as more documents have been added to the CfE?

It would be negligent not to recognise the existence of phronesis in the CfE, as there are ideals that can be linked to the moral aspect of education. The choice of words mentioned both in the national priorities and the Scottish values, which are both worthy and critical for a curriculum that is essentially democratic, nonetheless fail to provide further discussion on how they could be attained or why they were chosen indicates a lack of coherence and force. As a result, techne overtakes phronesis, where the latter is underestimated. As Gillies (Citation2006) notes with regard to the earlier documents of the CfE democratic values remain ‘a list of ill-defined concepts’ (Gillies Citation2006, 30). This tendency reveals an instrumental manner that permeates the curriculum and reveals that techne prevails.

Another consideration is the controversial relationship between heterogeneity and homogeneity. Heterogeneity encompasses a universal approach that encompasses diversity and an in-depth awareness of economic, environmental and political issues that exceed the local or the national. The CfE calls for an understanding of different cultures and an overall acceptance of diversity, yet within the Scottish context. National and local actions are highlighted several times in the curriculum, accompanied by contributions to the Scottish society and economy, as such the global dimension is neglected. Moreover, the individualistic character of the curriculum, where personal and individual responsibility is emphasised whereas collective or political aspects are barely mentioned or completely absent. This conclusion is drawn from the way citizenship and sustainability are conceived as the development of skills and dispositions (Biesta Citation2008). Such an approach creates a techne- and episteme-based curriculum, ignoring or underestimating phronesis and framing education as means of utilisation for a market-driven economy and society.

The four capacities at the heart of the CfE provide key insights into the type of knowledge promoted by the curriculum in relation to GCE. The structural form of the capacities corresponds with a wider global trend apparent in several modern national curricula with an instrumental slant, which is driven from economic techne-based outcomes and an intense focus on the individual. The individualistic tendency with the CfE is highlighted in the four capacities as a capacity is described as something that relies completely on the individual and his or her qualities and abilities (Biesta Citation2008; Priestley and Biesta Citation2013; Priestley and Minty Citation2013). Furthermore, the four capacities include overtones of indoctrination because the focus is not on ‘what children are expected to know, but how they should be’. The four capacities also provide an overly narrow conceptualisation of the ‘responsible citizen capacity’ as political and collective accountability is barely mentioned. As noted by Swason and Pashby (Citation2016), the CfE carries a futuristic agenda, shaped by economic rationalities influenced by neoliberalism, with an intrinsic tendency that focuses solely on national economic growth putting the global dimension aside. This tendency creates an economisation of non-economic spheres that reproduce ‘historical, social and material legacies of colonial relations based on imperialism, patriarchy, and racism’ (Shultz Citation2018, 249). In addition, this agenda promotes a western dominance that creates citizens who orient to themselves others, and the wider world through competitiveness that only responds to market conduct and demands.

The extent to which GCE is present in the CfE is as a cross-curricula theme and a ‘whole school’ approach suggests an instrumental character justified under modernist progressivity (Reeves Citation2008; Swason and Pashby Citation2016). The development of knowledge, skills and attributes to equip children with new knowledge in a rapidly changing world, while being able to apply them in different, and practical context, as such a reductionist and instrumentalist discourse is revealed as knowledge is neither defined nor granted deeper interrogation (Humes Citation2013). It would be naïve to suggest that neither the acquisition of skills nor the knowledge of techne and episteme is vital. It is the knowledge of techne and episteme that ensure practical and scientific advances, but the findings from this study highlight the absence of phronesis.

It is phronesis that will ensure that individuals are able to make wise decisions for the best of humanity and the natural world, while being able to overcome national and local boundaries, while taking into consideration local identities and needs. GCE is not about promoting a western superiority, but developing awareness, compassion and respect towards oneself and others. Thus, phronesis can be described as the disposition that guides and informs praxis, with praxis connected to right conduct. Kemmis underlines that phronesis should be ‘something to be taught as opposed to something that develops through experience as a capacity, instead to approach the unavoidable uncertainties of practice in a thoughtful and reflective way’ (Kemmis Citation2012, 148).

GCE with a phronesis orientation will deliberately provide spaces for reflection towards our own epistemological and ontological assumptions. Knowledge is constructed within our local cultures, experiences and contexts, but as such it is incomplete. A critical global citizenship calls for the personal awareness of how we came to act/think/be/feel in the way we do and realise the implications of our system of beliefs in local and global terms, and in relation to power, social relationships and the distribution of labour and resources. In addition, there is a need to engage with our own and with others’ perspectives in order to learn and transform our views/identities/relationships-to think otherwise (Andreotti Citation2011).

We suggest that GCE could be strengthened in national curricula with the introduction of the term ‘planetary phronesis’ to invoke a sense of connection to an imagined planetary community that encompasses nations and localities, harnesses the interconnected and dependencies existing in both GCE and sustainability, as inevitable powers. The notion of ‘planetary phronesis’ enables rights and responsibilities to exceed national boundaries of the local sphere, contributing to critical awareness and promoting social justice (Mansouri, Johns, and Marotta Citation2017; Pashby Citation2011).‘Planetary phronesis’ acknowledges the value of techne- and episteme-based knowledge but goes beyond local and national interest and recognises the contributions of both individual and collective responsibility. It will aim to enhance phronesis and praxis through critical reflections that understand relations of power, injustice, while developing local and global communities in which individuals and communities can flourish together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andreotti, V. 2011. “The Political Economy of Global Citizenship Education. Globalisation.” Societies and Education 9: 307–310.

- Bamber, P. 2020. Critical Global Citizenship Education: Teacher Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship. London: Routledge.

- Bergqvist, T., and E. Bergqvist. 2017. “The Role of the Formal Written Curriculum in Standards-based Reform.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (2): 149–168.

- Biesta, G. 2008. “What Kind of Citizen? What Kind of Democracy?” Scottish Executive Review 40: 38–52.

- Bryce, K., W. Humes, D. Gillies, and A. Kennedy. 2018. Scottish Education. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Canton, A., and I. Garcia. 2018. “Global Citizenship Education.” New Directions for Student Leadership 2018 (160): 21–30.

- Education Scotland. 2019, August 28. Refreshed Narrative on Scotland's Curriculum. Retrieved from Education Scotland: https://scotlandscurriculum.scot/.

- Fernekes, W. 2016. “Global Citizenship Education and Human Rights Education: Are They Compatible with U.S Civic Education?” Journal of International Social Studies 6: 34–57.

- Freire, P. 2017. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

- Gillies, D. 2006. “A Curriculum for Excellence: A Question of Values.” Scottish Educational Review 38: 1–12.

- Goren, H., and M. Yemini. 2017. “Global Citizenship Education Redefined – A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies on Global Citizenship Education.” International Journal of Educational Review 82: 170–183.

- Humes, W. 2013. “Curriculum for Excellence and Interdisciplinary Learning.” Scottish Educational Review 45: 80–93.

- Kemmis, S. 2012. Phronesis, Experience, and the Primary of Praxis. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kemmis, S., J. Wilkinson, C. Edwards-Groves, I. Hardy, P. Grootenboer, and L. Bristol. 2014. Changing Practices, Changing Education. London: Springer.

- Mahon, K., H. Heikkinen, and R. Huttunen. 2018. “Critical Educational Praxis in University Eco-systems Enablers and Constrains.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 27: 1–19.

- Mannion, Greg, Gert Biesta, Mark Priestley, and Hamish Ross. 2011. “The Global Dimension in Education and Education for Global Citizenship: Genealogy and Critique.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 9 (3-4): 443–456.

- Mannion, G., G. Biesta, M. Priestley, and H. Ross. 2014. “The Global Dimension in Education and Education for Global Citizenship: Genealogy and Critique.” In The Political Economy of Global Citizenship, edited by d. O. Andreotti, 134–147. London: Routledge.

- Mansouri, Fethi, Amelia Johns, and Vince Marotta. 2017. “Critical Global Citizenship: Contextualising Citizenship and Globalisation.” Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies 1 (1): 1–9.

- McSharry, M. 2016. The Critical Global Educator: Global Citizenship Education as Sustainable Development. London: Routledge.

- Muller, J., and M. Young. 2010. “Three Scenarios for the Future-Lessons from the Sociology of Knowledge.” European Journal of Education 45: 11–27.

- Pashby, K. 2011. “Cultivating Global Citizens: Planning New Seeds or Pruning the Perennials? Looking for the Citizen-Subject in Global Citizenships Education Theory. Globalisation.” Societies and Education 9: 427–442.

- Pashby, K., M. Costa de, S. Stein, and V. Andreotti. 2020. “A Meta-review of Typologies of Global Citizenship Education.” Comparative Education 56 (2): 144–164.

- Priestley, M., and G. Biesta. 2013. Reinventing the Curriculum: New Trends in Curriculum Policy and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Priestley, M., and S. Minty. 2013. “Curriculum for Excellence: ‘A Brilliant Idea, but … ’.” Scottish Educational Review 45: 39–52.

- Priestley, M., and C. Sinnema. 2013. “Downgraded Curriculum? An Analysis of Knowledge in New Curricula in Scotland and New Zealand. Curriculum Journal.” Special Education 25: 1–37.

- Reeves, J. 2008. “Between Rock and a Hard Place? Curriculum for Excellence and the Quality Initiative in Scottish Schools.” Scottish Educational Review 40: 1–11.

- Salter, P., and K. Halbert. 2017. “Constructing the [Parochial] Global Citizen. Globalisation.” Societies and Education 15: 694–705.

- Scottish Executive. 2004. A Curriculum for Excellence: The Curriculum Review Group. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

- Scottish Executive. 2006. A Curriculum for Excellence; Building the Curriculum 1, the Contribution of Curriculum Areas. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

- The Scottish Government. 2008. Curriculum for Excellence: A Framework for Learning and Teaching. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Shultz, L. 2018. “Global Citizenship and Equity: Cracking the Code and Finding Decolonial Possibility.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education, edited by I. Davies, D. Kiwan, C. Peck, A. Peterson, E. Sant, and Y. Waghid, 245–255. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Stein, S. 2017. “Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education.” Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review (27): 1–11.

- Swason, D., and K. Pashby. 2016. “Towards a Critical Global Citizenship? A Comparative Analysis of GC Education.” Discourses in Scotland, and Alberta. Journal of Research in Curriculum and Instruction 20: 184–195.

- Taylor, C. 2012. “Student Engagement, Practice Architectures Andphronesisin the Student Transitions and Experiences Project.” Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 4 (2): 109–125.

- Toukan, V. 2018. “Educating Citizens of ‘the Global’: Mapping Textual Constructs of UNESCO’s Global Citizenship Education 2012–2015.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 13 (1): 51–64.

- UNESCO. 2015. Global Citizenship Education: Topics and Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2019. Addressing Global Citizenship Education in Adult Learning and Education. Hamburg: UNESCO.