ABSTRACT

This article showcases digital inequalities that came to the forefront for online learning during the COVID-19 lockdown across five developing countries, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Afghanistan. Large sections of population in developing economies have limited access to basic digital services; this, in turn, restricts how digital media are being used in everyday lives. A digital divide framework encompassing three analytical perspectives, structure, cultural practices and agency, has been developed. Each perspective is influenced by five constructs, communities, time, location, social context and sites of practice. Community relates to gendered expectations, time refers to the lockdown period while locations are interleaved online classrooms and home spaces. Societal contexts influence aspects of online learning and how students engage within practice sites. We find structural issues are due to lack of digital media access and supporting services; further that female students are more often placed lower in the digital divide access scale. Cultural practices indicate gendered discriminatory rules, with female students reporting more stress due to added household responsibilities. This impacts learner agency and poses challenges for students in meaningfully maximising their learning outcomes. Our framework can inform policy-makers to plan initiatives for bridging digital divide and set up equitable gendered learning policies.

Introduction

While digitisation is transforming societies and spurring digital economic growth in most parts of the world, some segments of societies continue to lag. Digital inequality or unequal diffusion and adoption of digital goods and services are oft based on economic, social, geographical and generational divides (Maceviciute and Wilson Citation2018; Van Dijk Citation2012). An OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) report lays emphasis on another form of digital divide (DD), that is, digital gender divide (DGD). DGD refers to underlying gender-based digital discriminations that curtail women’s ability to benefit from emergent digital opportunities (Borgonovi et al. Citation2018). Women face more ‘hurdles to access, affordability, lack of education as well as inherent biases and socio-cultural norms’ which can get further exacerbated in times of crisis (13). However, there is no proper measurement to quantify the magnitude of existing gender inequities, and women are often the forgotten causalities especially in adverse situations (e.g. tsunami and pandemic) (Cutter Citation2017). A recent study reported gendered inequities (e.g. in frontline work, unpaid care work and community activities) that arose as a consequence COVID-19 pandemic across four countries (namely Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia) (McLaren et al. Citation2020); again, the study does not provide any quantifiable data. Our study has evaluated both quantitative and qualitative data related to DGD issues, as witnessed during the COVID-19 lockdown in parts of the developing world. Specifically, this study investigates digital access, digital inclusion and digital equity at the time when educational institutions were forced to shut on-campus teaching and switch to online teaching modes due to the raging pandemic. We surveyed male and female students from five developing countries (namely India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Nepal) to understand digital divide issues that had impacted online learning during the lockdown.

In developing countries, the gap in access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) between the haves (the privileged class) and the have-nots (the underprivileged class) is rather wide (Venkatesh and Sykes Citation2013). Here, societal set-ups are based upon complex socio-economic levels and geographical spread, where ‘majority of the population does not have access to basic capabilities such as healthcare and education’ (Srivastava and Shainesh Citation2015, 246), thus making access to ICTs low priority. Therefore, when students were forced to suddenly pursue studies from inside their homes, this gap would have had more impact among the have-nots. And if we are to consider common gender-based differences (like women bearing additional household burdens of cooking, cleaning and caregiving (Cutter Citation2017)), this situation would have placed female students lower in the have-nots scale. This study seeks to understand how male and female students fared with online learning in the lockdown situation. Our study is informed by Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair’s (Citation2010) socio-cultural framework and subsequent extension made by Bannan, Cook, and Pachler (Citation2016), as these studies apply to social adaptation based on cultural experiences across formal and informal learning spaces. Our work provides added context, since it focuses on student perceptions and uses student voices to convey different aspects of existing divides. Moreover, this is the first study that shares male and female student experiences in regard to online learning. We delineate three areas of observation related to DD studies, that is, structures, cultural practices and agency, in the context of the ongoing pandemic and limited infrastructural support available in developing countries. The research has both conceptual and practical values. Our research has reported many aspects of being ICT-challenged in present times, which have led to the further conceptualisation of digital divides in the context of online education in developing worlds. We have demonstrated how infrastructural and societal structures have widened digital divides, specifically for female students who are often left on the wrong side of this divide. The practical value of this research lies in highlighting concerns raised by students and bringing out their voices. These issues need consideration when planning future educational policies for facilitating more inclusive digital environments.

The next section gives a brief review of literature that informed our research agenda. Specifically, we discuss DD and the impact of COVID-19 lockdown in a gendered context. We build upon extended work of the socio-cultural framework (Bannan, Cook, and Pachler Citation2016; Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair Citation2010) that views formal and informal learning in the context of everyday lives, and advises researchers to consider deductive acts of analysis for balancing ecology, affordances and complexities that exist across inter- and intra-personal contexts surrounding technology access and its usage. Our analytical framework is proposed next, followed by a description of survey methods used. Findings from the study showcasing gender biases, which came to the forefront with the shift towards online education during the COVID-19 lockdown, are discussed. Finally, we present key gendered themes on prevailing DGD issues, which can assist in defining policies for positioning women on more equitable digital platforms.

Literature review

The COVID-19 pandemic has put much of the world in ‘pause’ mode. Earnings from mainstream economic activities such as trade and tourism are on hold, as governments worldwide have moved focus towards containing the deeply infectious human-to-human transmittable disease. ICTs have become key enablers for facilitating information sharing, continuing business operations and delivering remote or online education; however, in having said this, the issue of unequal diffusion and adoption of ICTs cannot be ignored. While the pandemic highlighted the importance of the digital economy, it also uncovered different forms of digital divides that exist among societies in developed and developing countries (Tadesse and Muluye Citation2020). Kasinathan and Ranganathan (Citation2020) state that while the virus by itself is not political nor gendered, it has exposed many social issues related to access, inclusion and gender equity. For instance, if societies do not have equitable access to digital tools and resources that can provide them with a stable online presence, digitisation will not be inclusive and not deliver them equal opportunities. Furthermore, many sub-divisions, such as generational and gendered sub-divisions exist across societal groups, wherein members of these sub-divisions have limited access to digital resources. Limited access to digital resources yields lesser digital opportunities, more so, for women in emergent education areas of study, or for those who prefer to work remotely from home due to family obligations (Borgonovi et al. Citation2018; Kaka et al. Citation2019). The following subsections discuss relevant literature on existing digital divides and some key findings from recent COVID-19 lockdown studies.

Digital divide literature

Past literature has highlighted three DD levels, namely digital access divide (DAD) or first level, digital capability divide (DCD) or second level and digital outcome divide (DOD) or third level (Wei et al. Citation2011). DAD refers to the gap in material access to digital tools in homes and in schools. These include device opportunity (i.e. ease in replacement of the device), device and peripheral diversity (i.e. total number of devices and associated peripheral equipment) and maintenance expenses (i.e. licensing and related subscription fees to services) (van Deursen and van Dijk Citation2019). Material access is positioned along with an economic, technological, social and cultural context. Based on their purchasing power, individuals participate with technological devices (that range from simple to advanced features) for extending online social interactions. In developing economies, household income level is not evenly distributed which results in significant gaps between the haves and the have-nots, and this unfortunately undermines an individual’s educational choices (Mishra Citation2018). Moreover, low-income households such as those located in rural or semi-urban regions are most affected by digital inequality (Maceviciute and Wilson Citation2018). Cultural norms can further impact device usage (or digital opportunities) which limits the users’ digital skills and capabilities. For instance, female users are more constrained in making full use of digital opportunities, as they may have to fit into gender-specific expectations often laid out in many households. This gendered outlook renders in the form of more familial opposition for girls compared to boys; the reasons for the lack of support could be due to fears related to the online safety of girls, financial constraints leading to lesser opportunities for daughters compared to sons and more household responsibilities faced by women, or as a direct consequence of general marginalising attitudes towards girls (Alozie and Akpan-Obong Citation2017; Borgonovi et al. Citation2018).

Lack of digital opportunity provides context to the second level divide or DCD. With limited experiences related to device usage, device diversity and technological subscriptions, users are limited in practice and therefore they lack relevant skills and capabilities. A study across five developing countries suggests gender divisions in digital ownership are often due to infrastructural issues, patriarchal attitudes and caste-based traditions (Rashid Citation2016). These socio-economic barriers limit the realisation of digital outcomes and lead to the third level of divide (DOD) where affected users lack belief and self-efficacy that further inhibits participation in the digital economy. A National Education Policy (NEP) document currently being developed by the Indian government recognises ongoing digital exclusionary practices prevalent among poor urban, tribal, caste and religion-based groups (Kasturirangan et al. Citation2019). This NEP document highlights digital technology diffusion to be an ongoing social divide problem that requires governments to facilitate equitable technological development activities alongside other basic infrastructural issues (e.g. electricity and network connectivity). Proposals are being made to create more inclusive schools and societies.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown

A recent study has highlighted how COVID-19 induced digital divides across all three levels in digitised education in a developing country context (Iivari, Sharma, and Ventä-Olkkonen Citation2020). DAD issues revealed situations where many families lacked access to internet, digital devices and learning applications. DCD issues showcased lack of skills and competencies regarding the proper use of digital media among parents, students and teachers. And, DOD reports were mixed, that is, while some students enjoyed the digital transformation, some others said they had missed out on their education altogether during the pandemic. Another study discusses the intersection between COVID-19 and gendered burdens (McLaren et al. Citation2020). This study highlights additional responsibilities that are cast upon females who are already in an inequitable position. That is, women are ‘tasked with the ongoing organization of their homes and families’ that further intensifies their subordinate position in households (4). Another study on online education at the time of the pandemic lockdown (that did not take a gendered perspective) highlighted some panic pedagogical attempts made by teachers, unaccustomed to online teaching, when they were left to fend on their own (Mishra, Gupta, and Shree Citation2020). Despite many digital tools (e.g. Zoom, Google Meet, WhatsApp and Facebook), teachers mainly used one tool, which was WhatsApp. Teachers noted this preference as a consequence of lack of digital infrastructure (e.g. slow network connectivity, power shutdowns and expensive internet data packs), and further since they were more accustomed to WhatsApp in comparison to other digital tools in their day-to-day lives. Therefore, DAD and DCD are predominant issues that need to be addressed.

Yet another study has discussed how the COVID-19 exacerbated inequalities across socio-economic background, education, gender, ethnicity and geography (Blundell et al. Citation2020). With household incomes impacted by job losses, business closures and loss of contractual work amongst others, gendered burdens were witnessed in many developing countries (e.g. Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Malaysia). Women are cast in domestic servitude, as they dutifully accept male privileges in their homes, take roles of primary caregivers for young children and elderly relatives, and become subservient towards acts of violence targeted at them (Hamadani et al. Citation2020). Household responsibilities are already unbalanced among genders across many countries and within cultures; unfortunately, these become even more unequal at times of crisis (McLaren et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, with school closures, parents deemed as essential workers or solo parents too are vulnerable. Many parents who had incurred income losses and faced financial hardships complained of further discrimination faced by their children (Singh Citation2020). Parents alleged that some schools had removed their child’s name from the online learning groups (e.g. WhatsApp classroom groups), since their school fees were not paid. All this has had a knock-on effect and further perpetuated existing economic, gender and generational inequalities.

Digital divide framework

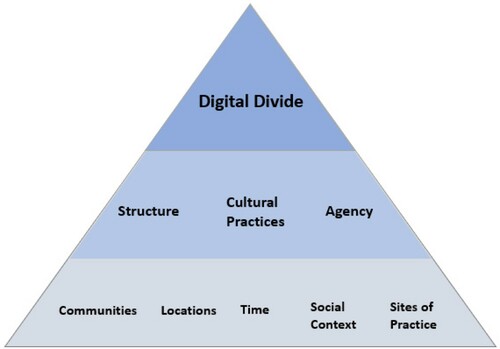

Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair’s (Citation2010) socio-ecological framework has provided the analytical underpinnings for investigating classroom teaching and learning practices with ICTs. The framework separates out three analytical perspectives, namely structure, cultural practices and agency. Structure relates to the blending of formal (school) and informal (out-of-school) contexts where ICTs are modes of appropriation. With the evolved technology landscape, learner-owned devices are seen as new routes towards learning. While schools were traditionally viewed as formal centres of collective learning, ICTs have changed learning to a more individualised and private context. Moreover, cultural practices surround learning in how ICTs are positioned in formal and informal learning spaces. Therefore, learning is a function of both the context and the culture, in which it occurs. By properly engaging with ICTs in both spaces, the habitus of learning evolves, as learners enhance their agency to achieve desired learning outcomes (Adhikari, Mathrani, and Scogings Citation2017). Learning is thus a social phenomenon ‘that does not take place in one location but also across communities, locations, time, social context and sites of practice’ (Bannan, Cook, and Pachler Citation2016, 941). However, Bannan, Cook, and Pachler (Citation2016) refer to learners as device users who leverage their devices when deliberating on pedagogical choices to frame their learning appropriately with technology. This study considers learners comprising the haves and the have-nots spread across communities located in different developing country regions during the stressful time of the raging pandemic. Societies in these regions often have gendered social expectations, as such learning sites of practice are much constrained by household responsibilities, unequal physical access and device support. These studies (e.g. Bannan, Cook, and Pachler Citation2016; Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair Citation2010) have helped produce layered constructs for our proposed digital divide framework in the context of online learning (see ).

Figure 1. Digital divide framework for online learning (adapted from Bannan, Cook, and Pachler (Citation2016) and Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair (Citation2010)).

The bottom layer comprises communities, locations, time, social context and sites of practice. Or in other words, community norms set out gender expectations, and individuals are tasked with duties that align with these expectations. These expectations may get further intensified at particular times such as when faced with difficulties like in the lockdown period during the pandemic (Bauza et al. Citation2021). The pandemic brought financial hardships to many families that caused additional gendered burdens, such as to those women living with extended families or living with young/elderly family members amongst similar others. Moreover, societal contexts can influence how ICTs align with genders. Women are more frequent users of older ICTs (e.g. television, landlines and radios) compared to men (who have mobile phones and internet data packs) (Rashid Citation2016). Furthermore, gender restrictions are location-specific, with women being much more confined in their homes and having routine household responsibilities set out for them compared to men, although the level of comfort available in family spaces can further enhance or lower gendered expectations. These together impact the second layer that considers ICTs as modes of appropriation across structures, cultural practices and agency. How much emphasis is given to formal and informal learning structures with the use of ICTs at times of crisis, or otherwise? Furthermore, what cultural practices surround the individual’s learning, as they have to make do with whatever ICT resources are available to them? Finally, how are learners encouraged and motivated in overcoming constraints that have been imposed by their surroundings so as to maximise agency to take charge of their own learning? In the design of our digital framework, the representation of the three analytical perspectives slightly deviates from Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair’s (Citation2010) figure comprising three intersecting circles. The three circles stand for structure, cultural practices and agency, and their intersection embodies ‘conversational activities of appropriation’ that occur in a learning context (3). By placing the three perspectives in the middle layer, we are laying emphasis on these ongoing conversations that together provide an analytical lens for investigating the bottom-layer constructs, and which can inform on digital divide issues. This layered digital divide framework embraces both Pachler et al.’s socio-ecological outlook and Bannan, Cook, and Pachler’s (Citation2016) view that learning is framed within communities, locations, time, social context and sites of practice.

Survey instrument

An online survey instrument was employed (between October 2020 and March 2021) when the COVID-19 lockdown was enforced in many parts of the world to understand student learning experiences. The instrument was floated to students across five countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Nepal). It included questions to help identify each respondent’s country, gender, age bracket, family income bracket and their level of study. Further questions were posed to gauge digital divide issues related to the respondent’s access (e.g. internet connectivity and digital device) and home environments (e.g. household responsibilities) and how online learning impacted them. Furthermore, open-ended questions were posed asking respondents to state positive and negative experiences with online learning. These open-ended questions provided ontological grounding (understanding of the reality of online learning incidents) and epistemological grounding (making subjective interpretation of the online learning encounters) (Twining et al. Citation2017). Care has been taken in maintaining participant anonymity, and the survey instrument did not gather any personally identifiable data whatsoever.

Quantitative findings

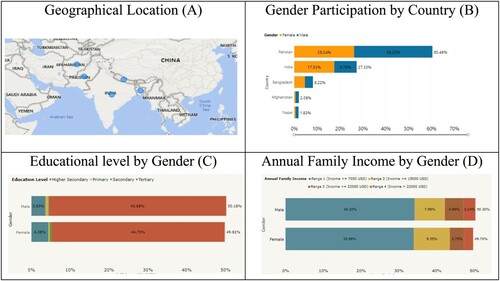

This section reports on quantitative findings that were gained from the survey data. A total of 827 students from Pakistan (60.4%), India (27.3%), Bangladesh (8.2%), Afghanistan (2.06%) and Nepal (1.93%) responded to our study (see (A,B)). Since these five countries are in close geographic proximity having some aspects of shared heritage and are close in global economic rankings (Hamadani et al. Citation2020), we have subsequently considered them as one big student cohort. Overall, the data were evenly balanced among male and female participants (i.e. 50.3% males and 49.7% females) with 90% of them currently pursuing a tertiary level of study (see (C)). Participants were queried across four annual family income (AFI) ranges, namely range 1 (AFI < 7000 USD), range 2 (AFI ≤ 15,000 USD), range 3 (AFI ≤ 22,000 USD) and range 4 (AFI > 22,000 USD). Of these, most students (male and female) belonged to ranges 1 and 2 (see (D)). Many societies in South Asian countries (e.g. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) struggle to live on 1.25 USD to 2.5 USD, which leads to unequal access to education, information and health amongst others (Khan, Saleem, and Fatima Citation2018). gives a brief overview of these statistics obtained from our survey.

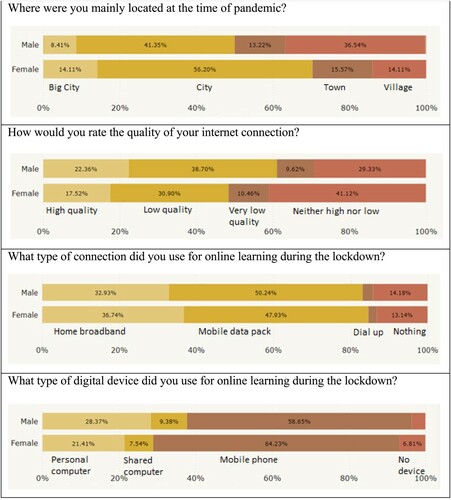

Approximately 50% of male students who responded to our survey were located in small towns or villages compared to 30% of female students at the time of the lockdown, although this rural–urban segregation has deeper roots than this number break-up. Many female students emailed us (via the email address provided on the survey link) that they could not participate in the survey because of lack of proper internet access. The survey comprised questions related to the quality of internet connection, type of connection and digital media used by students. Survey responses further show that female students mainly used their home broadband connection, whereas their male counterparts mostly used mobile data packs. Furthermore, 22.3% of male students ranked the quality of internet connectivity as high and 38.7% as low (with a further 9.62% calling it very low), while 29.3% ranked it as neither. On the other hand, 17.5% of female students ranked their connectivity to be of high quality, 30.9% of low quality (with a further 10.46% calling it very low quality) and 41.12% ranked it neither high nor low. Finally, in regard to the digital device used for online study, 28.4% of male students said they owned personal computers compared to 21.4% female students; moreover, 3.5% of male students did not have any device compared to 6.8% of female students.

Data also show that the female students mainly resided in urban or semi-urban areas (i.e. cities, big cities and towns) with only 14% reporting that they lived in rural regions or villages. In contrast, 36.5% of the male students lived in rural regions. However, despite the majority of females living in mainly urban locations, 41% of them considered their internet connection to be of somewhat poor quality, with an equal percentage saying they were not sure of how to rate their internet connection. In regard to the type of connection being used, we found similar reporting across male and female students. However, in terms of the type of device used, more male students reported having access to a computer, while female students mainly used mobile phones and another 6.8% reported not having any device. presents this part of the survey data.

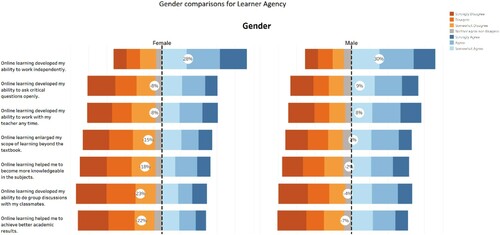

Next, questions (that were adapted from the questionnaire used by Wei et al. (Citation2011)) related to online learning were posed. These questions aimed to understand how students considered online learning to have impacted their overall learning (i.e. access to teacher, ability to work independently, ability to ask critical questions, achieve better academic results, enlarge scope of learning, ability to conduct group discussions with their classmates and overall to become more knowledgeable). Notably, the female students felt themselves more disadvantaged compared to the male students. provides an overview of all student responses categorised by gender.

Therefore, at a first glance, we find that female students are slightly more entrenched in digital inequalities that entail further social and educational differences. The next section provides a more in-depth analysis using qualitative details alongside the theoretical framework developed (shown in ) to seek answers to why such perceptions have been felt by female students.

Qualitative findings

This section provides deeper insights on digital gender divide issues when COVID-19 lockdowns forced students to continue their education online. The data extracted from responses to the open-ended questions have been analysed here. Thematic techniques have been applied to group similar concepts, frame discussions and synthesise results. Qualitative researchers are advised to use exemplars from their empirical data, as these can convey both depth and richness to participant voices which give a more compelling story (Spencer et al. Citation2003). The participant responses have been categorised based on the digital divide framework () that framed our investigation. The bottom-layer constructs, comprising communities, time, locations, societal context and sites of practice, have been analysed using the middle-layer analytical lens which is informed by structure, cultural practices and agency. Community norms relate to gendered expectations laid out in households. The time specifically refers to the COVID-19 lockdown time when students were constrained with limited resources and strictly confined to their homes. Locations refer to interleaved places that comprise online classrooms and home environments. These interleaved spaces provided the social context in which students engaged with learning during the lockdown period. Furthermore, learning practice sites were formed within these spaces (that were physically shared with family members and digitally shared with peers and teachers). This study aims to explore student experiences with online learning in such extraordinary situations to understand how students could (or could not) avail of learning opportunities.

Three analytical perspectives, namely structure, cultural practices and agency (Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair Citation2010), provided substantive focus in defining guidelines for making interpretations. These perspectives are explained next in the context of this study. Students overcome entangled structures that relate to formal and informal learning spaces (e.g. technological structures, digital media usage structures, communication structures and social structures) to engage in learning with ICTs. In doing so, they engage in social interactions and create user-generated content that is culturally dependent via collaborations, explorations and sharing of information. That is, the social, economic, cultural and technological aspects are embedded in how knowledge gets created. For instance, if familial restrictions are in place for using the mobile phone as a learning resource, or, if the phone has very basic features (e.g. it is not web-enabled or has very simple features or low storage), or, the user has limited internet access, then they will not be able to fully pursue new forms of inquiry to advance their literacy. Proper engagement with digital media is crucial for making full use of digital opportunities to enhance the learners’ agency (i.e. enhance ‘the capacity to construct a personal life-world and use media for meaning-making’ (Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair Citation2010, 10)).

Structure

Structure refers to real-world physical spaces comprising communities, locations, specific times, social context (e.g. communication devices, technological infrastructure and home spaces) and learning practice sites within which individuals (i.e. students in this case) engage with their learning. Structure themes that emerged from male students comprised internet issues (i.e. slow speed, poor connectivity and low quality of signals), electricity issues (i.e. frequent power cuts due to load shedding), network issues (i.e. low mobile data package and 2G mobile set-up in villages) and lack of books. While all these themes matched with the female student responses, the female students voiced some more issues regarding lack of proper devices (i.e. phone screens being small and inadequate, having to share devices with other family members), disturbance at homes leading to mental stress and difficulty in attending online classes due to household work burdens. We have listed a few exemplar quotes in regard to the themes which are presented in .

Table 1. Some respondent quotes highlighting emergent structural themes.

Cultural practices

These practices refer to informal contexts, that is, how online learning is located in everyday lives and how conversations occur around the technology appropriation for educational practice. The emphasis given to education and to the use of digital media in formal and informal environments is shaped by societal norms. At the time of the enforced lockdowns, family members were forced to stay inside their homes by necessity; however, they were also obliged to fulfil other commitments that earlier did not form such a big part of their daily routine. Earlier, they could go to external spaces (i.e. physical classroom spaces and office spaces), while now the household responsibilities could not be avoided. Cultural themes that were identified from male and female perspectives included household disturbances (i.e. noise and study interruptions), lack of physical space for online study, lack of proper schedule, financial constraints and lack of digital media. The female students identified further issues related to additional household chores, responsibilities of taking care of younger siblings and lack of support from parents. Some exemplars highlighting these themes are presented in .

Table 2. Some respondent quotes highlighting emergent cultural practice themes.

Agency

Our social environments can augment (or reduce) our learning capabilities based on how we acquire knowledge (with ICTs in this study’s context) and apply it in an everyday context. That is, with supportive structural surroundings and emotionally positive socio-cultural norms, students can confidently participate in building up their learning practice to open up new digital opportunities for themselves. But, in the advent of not being able to negotiate within their communities (comprising family members, peers and teachers), the individual’s learning is limited to fewer opportunities. Individuals will not be able to negotiate and re-negotiate their self-representation within emergent structural and cultural dictates to properly shape their learning outcomes resulting in a lack of agency. Agency relates to the ability to link ICTs as positive learning resources for enhancing learning outcomes via the production of cultural objects (e.g. videos and online presentations) that can be integrated into social structures (i.e. in formal (classroom) and informal (home) environments). Our data find that both male and female students reported less positives compared to negatives, with female students reporting even more negatives. Positives included access to lecture recordings, no travel time and flexible learning hours. Overall, the negatives included lack of pedagogical strategy in teaching and assessment, inability to access books and sitting for long hours in front of a screen. Additional challenges cited by female students include less classroom interaction, not much guidance on subject content and lack of confidence in communicating over digital media. presents some exemplar quotes showcasing agency and also lack of agency.

Table 3. Some respondent quotes highlighting positive and negative agency themes.

Discussion

This study has imparted awareness on some of the digital divide issues and also some digital gender divide issues that came out to the forefront when educational institutions were forced to move to digital platforms during the COVID-19 lockdown. While technological infrastructure, broadband coverage and low data packages are being touted as mediating factors for bringing together a more inclusive digital world in developing societies, the reality is not that simple. Digital inclusiveness is more deep-rooted, as communities’ outlook towards who can make more use of available technology fully and the social contexts surrounding their usage at specific locations are also other mediating factors. Inclusiveness is further negated in times of hardship (or crisis), as individuals are constrained in how they can engage with technology to build online learning sites of practice from within their homes. This calls for a more layered analysis of the haves and the have-nots who are positioned on either side of the digital divide.

This study has been conducted in five developing countries that share a close geographical proximity to each other. Our survey data have revealed many aspects of the digital divides faced by students in these countries. For one, this study has provided evidence of first-level divide or digital access divide, with some more emphasis on digital gender divide. We found that many households do not have access to a proper internet-enabled device and broadband internet service. This inequality in physically accessing digital media and communication services from an internet service provider has further impacted their digital capabilities and overall confidence to meaningfully leverage digital media. These societies (and students in particular) therefore lack digital capabilities to enable the transformation of digital goods to desired outcomes (Srivastava and Shainesh Citation2015). We further find that society at large in developing worlds faces technology diffusion issues, which impact their online educational delivery.

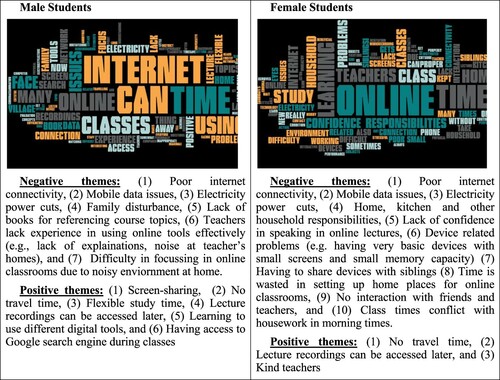

The study has further demonstrated many aspects of gendered digital divides as a consequence of socio-cultural and familial divides. presents word clouds generated from the open-ended questions to showcase emergent digital divide themes by gender. We find that male students were negatively affected mainly by poor internet connectivity issues, mobile data issues, power cuts, noisy families, lack of reference books, teacher issues and difficulty in focusing from their homes. Positive themes that were voiced include screen sharing opportunities, new experiences with technology (e.g. using Google search engines) and not having to make the daily commute to study on-campus. Alongside these negatives, female students reported further issues such as having very simple devices, having more household responsibilities, not being able to meet classmates, having to take care of siblings and very busy morning schedules where their kitchen responsibilities conflicted with online class timings amongst others. The female students did not report much positive experience, though some stated that if digital infrastructure improved, then they would have not wasted so much time and would have made better use of online learning. Female students were also much appreciative of their teachers who they said were very kind and helpful at these times. All students, however, realised the urgent need for home isolation in the time of pandemic crisis and understood that the lockdown was a necessity which they had to accept. Overall, digital access in terms of device ownership, internet connectivity and electricity cut downs were major factors that hindered their online learning.

We find that most students are still to cross the digital access divide (DAD). Wei et al. (Citation2011) define digital divides as a chain effect, wherein the first-level divide is followed by the second-level (capability) divide and then by the third-level (outcome) divide. They add that more needs to be done by developing countries to position ICTs evenly and also in laying out more socially responsible digital policies. The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportune time to highlight existing digital divides, with further focus on digital gender divides. Our study shows that female students reported lack of confidence in being able to effectively engage in online classrooms, while male students reported that they enjoyed learning to use new digital tools. Hargittai and Shafer (Citation2006) too found that women are more moderate in assessing their online skills often ranking it in the medium range which in turn impacts their online behaviour. Our study too has revealed similar perception. Furthermore, when asked how online learning impacted their overall learning, we find that female students felt more disadvantaged compared to the male students despite that more female students were in urban areas compared to their male counterparts (refer and ). The study has further demonstrated many digital divides and gendered sub-divides. Digital gendered sub-divides were evident in socio-cultural and family structures. Female students reported additional household responsibilities (e.g. cooking and taking care of siblings) that were not voiced by male students. This negatively impacts learner agency and further restricts girls from making full use of digital opportunities. However, our study finds that boys too face many digital divide hurdles, although they faced less familial opposition and had fewer household responsibilities.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted many aspects of digital divides especially in the context of genders. The study calls for more resources to be put across by local government bodies so that formal education can be effectively transferred to online platforms. Our study affirms the existence of digital divides at all three levels (access, capability and outcome) and also across genders at the time when students moved to online study during the lockdowns imposed in developing countries. Policy-makers need to find ways to bridge the prevailing divides by installing network infrastructure and scaling internet access across urban and rural areas wherever it is possible for them (Tadesse and Muluye Citation2020). Educational governance strategies are influenced by ‘the state, the market, the community and/or the families’, as both the hard laws (government policies) and the soft laws (socio-cultural norms) together frame how educational transformation will take place (Verger, Novelli, and Altinyelken Citation2018, 8). Therefore, a deeper education policy analysis is required so as to bring new reforms that can put women on a more inclusive digital path in the emerging education landscape.

The pandemic was indeed a challenging time for all, at the global level, the individual level and the gender level. Students were much affected, with many of them not being able to advance their studies due to inadequate infrastructure, lack of familiarity with the new form of educational delivery and additional stresses due to uncertainty surrounding the spread of the disease (Tadesse and Muluye Citation2020). Our study has brought more perspective to these challenging times; this is especially important, as online education is being touted as a mode of education delivery for the future. Developing countries need to prioritise digital technologies at the grass-roots level for all citizens. There is no sign of the virus abating. Therefore, we urge policy-makers to give proper consideration to students, that is, students are not to be treated in a diminished context, where they must accept being positioned at the wrong end of the digital divide. More studies are needed to highlight issues related to current online learning situations. We find that students (and more so female students) are stuck at the first-level digital divide (or DAD) and hence cannot move to the second level (DCD) and subsequently to the third level (DOD). Gender discriminatory attitudes combined with limited infrastructural support further marginalise women and place them on inequitable platforms. Furthermore, our proposed digital divide framework () extends prior works (Bannan, Cook, and Pachler Citation2016; Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair Citation2010) related to online learning and contributes to methodological inquiry for interpreting digital divide issues. We have demonstrated five constructs that underpin any digital divide phenomenon, although our focus has been towards students at the time of the pandemic lockdown. However, this framework can be applied to study more forms of digital divides (e.g. generational and professional) for study participants belonging to different categories (e.g. teachers, nurses and caregivers) across developed and developing country contexts.

This study has showcased prevalent inequities in the usage and access of digital media. The world has changed, and earlier used approaches for teaching and learning, socialising and travelling are being re-aligned with digital media. Therefore, our study is timeous in assisting policy-makers to prioritise technology inclusion and diffusion strategies across income- and gender- groups in their countries and define suitable digital initiatives to position their societies on a more equitable global platform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adhikari, J., A. Mathrani, and C. Scogings. 2017. “A Longitudinal Journey with BYOD Classrooms: Issues of Access, Capability and Outcome Divides.” Australasian Journal of Information Systems 21, doi:10.3127/ajis.v21i0.1693.

- Alozie, N. O., and P. Akpan-Obong. 2017. “The Digital Gender Divide: Confronting Obstacles to Women’s Development in Africa.” Development Policy Review 35 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1111/dpr.12204.

- Bannan, B., J. Cook, and N. Pachler. 2016. “Reconceptualizing Design Research in the Age of Mobile Learning.” Interactive Learning Environments 24 (5): 938–953. doi:10.1080/10494820.2015.1018911.

- Bauza, V., G. D. Sclar, A. Bisoyi, A. Owens, A. Ghugey, and T. Clasen. 2021. “Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Rural Odisha, India: Knowledge, Preventative Actions, and Impacts on Daily Life.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (6): 2863. doi:10.3390/ijerph18062863.

- Blundell, R., M. Costa Dias, R. Joyce, and X. Xu. 2020. “COVID-19 and Inequalities*.” Fiscal Studies 41 (2): 291–319. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12232.

- Borgonovi, F., R. Centurelli, H. Dernis, R. Grundke, P. Horvát, S. Jamet, M. Keese, A. Liebender, L. Marcolin, D. Rosenfeld, and M. Squicciarini. 2018. Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. Australia: OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation (STI), Directorate for Education and Skills (EDU) & Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs (ELS). https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf. Accessed on 10-06-2021.

- Cutter, S. L. 2017. “The Forgotten Casualties Redux: Women, Children, and Disaster Risk.” Global Environmental Change 42: 117–121. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.12.010.

- Hamadani, Jena Derakhshani, Mohammed Imrul Hasan, Andrew J. Baldi, Sheikh Jamal Hossain, Shamima Shiraji, Mohammad Saiful Alam Bhuiyan, Syeda Fardina Mehrin, et al. 2020. “Immediate Impact of Stay-at-Home Orders to Control COVID-19 Transmission on Socioeconomic Conditions, Food Insecurity, Mental Health, and Intimate Partner Violence in Bangladeshi Women and their Families: An Interrupted Time Series.” The Lancet Global Health 8 (11): e1380–e1389. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1.

- Hargittai, E., and S. Shafer. 2006. “Difference in Actual and Perceived Online Skills: The Role of Gender.” Social Science Quarterly 87 (2): 432–448. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00389.x.

- Iivari, N., S. Sharma, and L. Ventä-Olkkonen. 2020. “Digital Transformation of Everyday Life – How COVID-19 Pandemic Transformed the Basic Education of the Young Generation and Why Information Management Research Should Care?” International Journal of Information Management, 102183. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183.

- Kaka, N., A. Madgavkar, A. Kshirsagar, R. Gupta, J. Manyika, K. Bahl, and S. Gupta. 2019. Digital India: Technology to Transform a Connected Nation. McKinsey Global Insitute. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/ourinsights/digital-india-technology-to-transform-a-connected-nation. Accessed on 10-06-2021.

- Kasinathan, G., and S. Ranganathan. 2020. “Reclaiming Education During a Pandemic.” Deccan Herald. https://itforchange.net/reclaiming-education-during-a-pandemic.

- Kasturirangan, K., V. Kamat, M. Bhargava, R. S. Kureel, T. V. Kattimani, K. M. Tripathy, M. Asif, M. K. Sridhar, R. P. Gupta, and S. T. Shamsu. 2019. National Education Policy (Draft) India. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/Draft_NEP_2019_EN_Revised.pdf. Accessed on 10-06-2021.

- Khan, A. Q., N. Saleem, and S. T. Fatima. 2018. “Financial Development, Income Inequality, and CO2 Emissions in Asian Countries Using STIRPAT Model.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25 (7): 6308–6319. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0719-2.

- Maceviciute, E., and T. D. Wilson. 2018. “Digital Means for Reducing Digital Inequality: Literature Review.” Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 21: 269–287. doi:10.28945/4117.

- McLaren, H. J., K. R. Wong, K. N. Nguyen, and K. N. D. Mahamadachchi. 2020. “COVID-19 and Women’s Triple Burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia.” Social Sciences 9 (5), doi:10.3390/socsci9050087.

- Mishra, A. K. 2018. “Household Income Inequality and Income Mobility: Implications Towards Equalizing Longer-Term Incomes in India.” International Economic Journal 32 (2): 271–290. doi:10.1080/10168737.2018.1480640.

- Mishra, L., T. Gupta, and A. Shree. 2020. “Online Teaching-Learning in Higher Education During Lockdown Period of COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Educational Research Open 1: 100012. doi:10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012.

- Pachler, N., J. Cook, and B. Bachmair. 2010. “Appropriation of Mobile Cultural Resources for Learning.” International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning 2 (2): 1–21. doi:10.4018/jmbl.2010010101.

- Rashid, A. T. 2016. “Digital Inclusion and Social Inequality: Gender Differences in ICT Access and Use in Five Developing Countries.” Gender, Technology and Development Policy Review 20 (3): 306–332. doi:10.1177/0971852416660651.

- Singh, H. P. 2020. “Parents Protest Against Private School, Demand Fee Waiver.” Hindustan Times, September 14. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/parents-protest-against-private-school-demand-fee-waiver/story-qjnxwEOrrmTG4EizhIbLGL.html.

- Spencer, L., J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, and L. Dillon. 2003. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. London: The Cabinet Office.

- Srivastava, S. C., and G. Shainesh. 2015. “Bridging the Service Divide through Digitally Enabled Service Innovations: Evidence from Indian Healthcare Service Providers.” MIS Quarterly 39 (1): 245–267. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.1.11.

- Tadesse, S., and W. Muluye. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Education System in Developing Countries: A Review.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 8: 159–170. doi:10.4236/jss.2020.810011.

- Twining, P., R. S. Heller, M. Nussbaum, and C.-C. Tsai. 2017. “Some Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Qualitative Studies.” Computers & Education 106: A1–A9. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.002.

- van Deursen, A. J. A. M., and J. A. G. M. van Dijk. 2019. “The First-Level Digital Divide Shifts from Inequalities in Physical Access to Inequalities in Material Access.” New Media & Society 21 (2): 354–375. doi:10.1177/1461444818797082.

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. 2012. The Evolution of the Digital Divide: The Digital Divide Turns to Inequality of Skills and Usage. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Venkatesh, V., and T. A. Sykes. 2013. “Digital Divide Initiative Success in Developing Countries: A Longitudinal Field Study in a Village in India.” Information Systems Research 24 (2): 239–260. doi:10.1287/isre.1110.0409.

- Verger, A., M. Novelli, and H. K. Altinyelken. 2018. Global Education Policy and International Development: New Agendas, Issues and Policies. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Place.

- Wei, K. K., H. H. Teo, H. C. Chan, and B. C. Y. Tan. 2011. “Conceptualizing and Testing a Social Cognitive Model of the Digital Divide.” Information Systems Research 22 (1): 170–187. doi:10.1287/isre.1090.0273.