ABSTRACT

This research explores how geopolitics and ‘Neo-tributary’ relations influence the distribution of TNHE partnerships in China. Specifically, this research situates China’s TNHE cooperation in policy reforms and designs since 2010, and explores how geopolitics influences the regional practice of re-organisation of the joint programmes between 2018 and 2020. The findings show that, on one hand, China’s central government prioritises the TNHE partnerships in China’s local regions: East China, Central China and West China; and on the other hand, alongside the traditional partner countries, such as the UK and the US, the emerging BRI region enjoys more new Sino-foreign HE partnerships than other foreign partners. This research develops the discussion based on the categories of trade and diplomacy linkages; cultural assimilation; and image building (Pan, Su-Yan, and Joe Tin-Yau Lo. 2017. “Re-Conceptualizing China's Rise as a Global Power: A Neo-Tributary Perspective.” The Pacific Review 30 (1): 1–25.), and concludes with some of the implications of these trends on the ‘new’ geopolitics of knowledge in a Neo-tributary system.

Introduction

‘Geopolitics’ refers to territorial control and expansion as states vie for power and seek to exert influence on other states, and is about mastering both territorial and relational spaces and producing spatial orders through discourses and practices (Moisio Citation2018a). Viewed within a geopolitical discourse, this research argues that higher education in China serves two geopolitical functions. On the one hand, higher education in China has been widely considered to be among the most effective methods to accelerate economic development. Government leaders incorporate higher education into economic and social development planning in certain regions of the country. A series of policies since 2010, including the Chinese Ministry of Education’s (MoE) National Outline for Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020), makes the case for this role for higher education very clear (MoE Citation2010). On the other hand, China and its institutions of higher education exist in a soft power context and are geopolitical instruments that play a role in the country’s projection of soft power in overseas regions. With the re-emergence of the country on the global stage, the Chinese government has developed policies and initiatives in international relationships under what could be described as a conceptualisation of ‘Neo-tributary’ relations to meet its ambition of securing international recognition (Pan and Lo Citation2017). China’s main contemporary diplomacy is the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) promulgated in 2013 that aims to secure its position in a reconnected Eurasian continent. To that end, in the higher education sector, Chinese institutions – principally its ‘top’ universities – serve as the tools of knowledge diplomacy for the country’s soft power promotion (Metzgar Citation2016) and will play a role in the BRI.

As part of these developmental efforts, transnational higher education activities play a flagship role. In China, the State Council (Citation2014) clearly emphasised the importance of the concept of regions in TNHE cooperation and stressed that regions are not only economically connected and integrated, but will also strategically carry the national or regional missions for global integration and competition. Thus, TNHE cooperation has become part of an evolving strategy to drive economic and social progress at home and acquire greater prestige in the global context, particularly, in the Eurasian continent. Therefore, the scale of transnational higher education in China is growing steadily, having more than 2000 TNHE programmes up until 2018 (ICEF Citation2018), with a majority of them as Sino-foreign joint programmes.

In 2018, the MoE reviewed the existing joint programmes and institutes and acted to terminate 234 joint programmes and institutes that were faced with problems such as insufficient high-quality educational resources and uncompetitive professional subjects, which could not meet the requirement for regional and national development. Alongside these terminations, however, there were some partnerships that started in certain regions. The MoE approved 58, 74 and 83 Sino-foreign joint programmes in 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively, in specific regions at home and abroad. These moves by the MoE significantly contributed to the reorientation of the TNHE strategies of the state across policy and operational fields in China and are testimony to the growing importance of China’s higher education geopolitics.

This research, using the case of China, brings the regional element into the TNHE cooperation in geopolitical discourse. It is important to note that the term ‘region’ here is defined in geographic terms. Regions in this research specifically refer to China’s subnational regions (including six geographic city-regions) and supranational regions, notably the emerging ‘BRI region’ or the Eurasian region (Leskina and Sabzalieva Citation2021). This research draws upon these geopolitical perspectives and applies them to the Chinese TNHE strategy. It further contributes a perspective that includes the role of regions with increased transnational higher education activities in national and international standing (Mok Citation2019) and raises questions about the connection between territoriality and TNHE policy and practices by examining these areas together under the Neo-tributary framework.

The research questions are as follows:

How do national policies incorporate the aspect of geopolitics in the formation of TNHE partnerships?

What is the regional distribution of new Sino-foreign TNHE partnerships that were started between 2018 and 2020, especially the Sino-foreign joint programmes?

What are the implications and connections between territoriality and TNHE policy and practices?

This research proceeds as follows: first, it presents a geopolitical theory and relates it to the regional level under a Neo-tributary framework which underpins the analysis of China’s TNHE strategies and practice. Then the research outlines the research methods, presents the findings to answer the research questions and offers a discussion. Finally, this research concludes by identifying implications and future questions.

Understanding ‘regional’ geopolitics in neo-tributary of China’s TNHE

The conceptualisation of regional geopolitics and Neo-tributary fits within China’s TNHE policy designs and practices. In the geopolitical discourse, higher education with multiple identities (Knight and Woldegiorgis Citation2017) is not a purely pragmatic and technocratic enterprise, but as a site of strategic action for states to pursue their strategies and to realise their goals (Jessop Citation1990). According to Jonas (Citation2013) and Moir, Moonen, and Clark (Citation2014), regions with a clear spatial pattern are strategically, materially, and symbolically functional spaces with a superior ability for nation-states to make progress. Moisio (Citation2018b) extends the national and international strategic roles that regions play during the age of post-Fordist capitalism, which refers to the increasing central role of regions in the strategies of state governments that seek to build nation-states as territories of wealth, power and belonging, to the contemporary capitalist setting. As a part of this, some regions are becoming significant actors in national and international forums (Herrschel and Newman Citation2017; Moisio and Jonas Citation2018), and national governments committed to both international competitiveness and pursuing the national economic success of the territorial state have a tendency to favour the already and emerging high-performing regions at home and abroad (Crouch and Le Galès Citation2012; Jonas Citation2013).

In addition, in the higher education policy area, institutional arrangements at the national and regional levels can be shaped and constrained by policy paradigms, state strategies, projects and policies (Jessop Citation2008). Ransom (Citation2018) added that with the growing influence of regions as international actors, a strategic focus on regions and their interplay with their educational institutions by the state has been announced. Thus, at the regional level, we suggest that this discourse positions the geopolitics of higher education in a particular way that there is a strong relationship between higher education and the regions in which they are based (Christopherson, Gertler, and Gray Citation2014), underlining the importance of understanding the interaction between the two by the state (Ransom Citation2018).

However, it is possible to draw upon perspectives that consider a stronger historical context of China’s international relations and also a greater attention to its peculiar ‘Chinese characteristics’ with respect to its HE internationalisation strategies (Lo and Pan Citation2021). Pan and Lo (Citation2017) propose a Neo-tributary framework to describe China’s strategies with international actors. This framework draws from China’s historical international relations to interpret its contemporary strategy. This approach, they claim, avoids the pitfalls of a purely conventional realist IR perspective that does not explain Chinese efforts to engage in military diplomacy rather than a straightforward arms race with the West (Wang Citation2011). It also avoids applying certain kinds of neoliberal perspectives that focus on soft-power, primarily as an attractive force. In contrast to this, Chinese policies contain consensual but also coercive features – as featured in the debates over the economic implications of its BRI-related infrastructure financing (Singh Citation2020).

The Neo-tributary framework differs from the original imperial tributary system (206 BCE–220 CE). Pan and Lo (Citation2017) review the features of the original framework which positioned China as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ and in a position of East Asian hegemony. Tributary states had to pay tribute to the Chinese emperor and adopt Chinese diplomatic practices to be able to trade. Diplomacy and trade would then culturally assimilate foreigners (Fairbank Citation1983a, Citation1983b). The tributary framework contained six consistent features: ‘Sino-centrism; acceptance of China’s East Asian hegemony; institutionalised rituals and norms regulating China’s hierarchical relations; China-centric circles of tribute and trade relations; cultural assimilation into Confucianism; and China’s projected benevolent, non-coercive image’ (Pan and Lo Citation2017). However, these features necessarily need modification to be applied to China’s current situation. Pan and Lo argue that it has value as an analogical device to ‘further discussions on past and present Chinese foreign policy and to hypothesise the tributary mentality’s contributions to China’s contemporary diplomacy’ (Pan and Lo Citation2017).

The Neo-tributary system thus contains new analytic categories: Chinese exceptionalism, trade and diplomacy, cultural assimilation and image building. The first serves as the motivation for the overarching international strategy. Trade and diplomacy serve as the (economic) means of implementation. The third, cultural assimilation is the central feature of its political strategy. Finally, image building is the tool to defend China’s overall legitimacy. These features can also be used to understand the regional role in TNHE partnerships.

Literature review

In terms of the geopolitical TNHE studies, the limited literature on the geographies of TNHE focuses on the performance of the national level, and primarily interactions and response towards globalisation and regionalisation in national-global approach. Pan and Lo (Citation2017) argue that many of the perspectives that aim to interpret the Chinese geopolitics to draw upon previous studies of European colonialism and also of post-Cold War US international relations (IR) theories. This is true to a varying extent in a range of well-designed studies. For instance, Neubauer (Citation2012) outlines some of the historic ways of reviewing geopolitical patterns of Asia/Pacific regional engagement, particularly, by China in terms of higher education governance, citizenship and university transformation. Wu (Citation2019) investigates China’s present approach of using ‘outward-oriented’ higher education internationalisation as a geopolitical instrument for international status and image enhancement through its cultural diplomacy based on Sino-foreign higher education collaboration (i.e. the Confucius Institute programme), international development aid in higher education, and international student recruitment at the higher education level, especially in the BRI region. Mok et al. (Citation2021) argue how China in the Asia – Pacific region, has promoted nationalism in subnational regions through higher education.

However, less is known about the dis-aggregated distribution of higher education activities in regions at home and abroad (Mok Citation2019), especially with respect to the choices and debates about THNE cooperation.

As for the TNHE from China’s geopolitical perspective at a regional level, there are a growing number of governmental reports, academic articles, blogs and conference presentations addressing different aspects on such topics. But to the best of our knowledge, there are no publications that offer a comprehensive overview to unpack the geopolitical strategies through the lens of TNHE cooperation at the regional level with the neo-tributary approach and this deserves further study.

Methodological notes

This research adopts two methods to address its research questions. On one hand, as texts are understood as snapshots of policy discourses and policy is a site of powerful discourses with particular assumptions, values and signs (Ball Citation1993), this research interprets the actions and normative positions taken by the government as a constitutive part of the discourse (Rizvi and Lingard Citation2010), by analysing policy texts principally from the central government during the period from 2010 to 2020, which are publicly available through searching the Web, and national statistics. The concepts about themes, such as the importance of regions, were coded inductively (Gibbs Citation2014) using NVivo, through the analysis of repetition of the phrases or ideas relevant to the research questions and later amalgamated for a broader relevance. On the other hand, another typology applied in this work is the practice review of all TNHE cooperation with the focus on the Sino-foreign joint programmes between 2018 and 2020 published by the MoE, particularly, the terminated and newly approved joint programmes to interpret basic trends and patterns. The research presents the below findings regarding (1) the TNHE documents of policy and regulation containing geopolitical priorities released by the central government and (2) TNHE cooperation activities with a focus on the re-approval of Sino-foreign joint programmes by China’s MOE between 2018 and 2020.

Research findings

Here, we present the TNHE policies containing regional strategies and the newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes between 2018 and 2020 in detail.

Finding 1: China’s six subnational regions

Geographically, in China, 31 provinces and municipalities are categorised into six regions including South China, East China, North China, West China, Central China and North-east China (see ). They have strong complementary functions to support national economic growth, promote coordinated regional development and participate in international competitive cooperation (State Council Citation2014).

Table 1. Subnational regions in China.

As they have different performances based on the level of economic development and further development potential and serve different national strategies, they belong to developed, emerging, and underdeveloped groups with different national policy parameters. The regions such as the eastern part of China are identified as the core areas: important platforms for the country’s economic growth and international competitiveness with policy priorities. For example, as the traditionally developed region coupled with the economic, scientific and technological centres, East China comprising Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Jiangxi and Anhui provinces, is always a priority area in policy making circles as an area to host international cooperation at a higher level and to play its important supporting and leading role in the country’s economic and social development (State Council Citation2014).

Furthermore, the National New Urbanisation Development Plan (2014–2020) also emphasises the balanced development of land and space. More policy support and resources are poured into some of the emerging regions with economic and political development potential, among which are central and western parts of China; these are beginning to capture greater attention from the central government. As the Central and Western parts of China are located geographically on the Silk Road Economic Belt, regional cooperation with Central Asia and the whole Eurasian continent is identified as a priority to be promoted in these regions.

Finding 2: national government policies: TNHE and the regional strategies

China began to allow foreign universities to offer education programmes in collaboration with local institutions in the mid-1990s as a part of its efforts to meet growing demands for higher education, to modernise and improve the quality of Chinese higher education, and to contribute to the development of the broader development needs of China (QAA Citation2017). There are a series of documents that set out the importance of educational reforms and international partnerships to enhance the nation’s global position, influence, and competitiveness in the field of education (MoE Citation2010), and clearly stating that the key regions in China from a geopolitical perspective would enjoy a certain priority in terms of the TNHE cooperation.

The table below chronologically shows the key policy documents during the period 2010–2020 related to regional priorities and TNHE (see ).

Table 2. Geopolitical-related policy documents on TNHE.

These documents show that the policies are designed, on one hand, to serve the overall strategy of regional development of the country by promoting the coordinated development of education in the east, central, and western regions; and on the other hand, to emphasise the strategic priority of the countries from the BRI region.

In terms of regional development, the main themes in these policy documents are the sustained focus on education modernisation which includes TNHE cooperation as a component and the desire to address regional needs, in particular, through partnership activities with foreign countries. Specifically, from the policy document findings, it clearly shows the East China, Central China and West China areas are repeated in policies and enjoy national priority, such as in ‘The National Outline for Mid and Long Term Education Planning and Development (2010–2020)’ (Hereinafter, referred to as ‘National Outline 2010–2020’) (State Council Citation2010), ‘ Higher Education Revitalisation Plan In the Central and West China (2012–2020)’ (Hereinafter, referred to as ‘Higher Education Revitalisation Plan 2012–2020’) (MoE Citation2010), ‘The Acceleration of the Implementation of the Education Modernisation Program (2018–2022)’ (Hereinafter, referred to as ‘The Acceleration 2018’) (State Council Citation2018), ‘Acceleration of the opening up of education in the new era’ (Hereinafter, referred to as ‘Acceleration 2020’) (MoE Citation2020) and ‘The Key Work of the MOE’ in 2019 (Hereinafter, referred to as ‘The Key Work 2019’) (MoE Citation2019), which are a series of documents listing concrete goals to be achieved in terms of development of the regional layout. These documents are designed by the central government to reduce the unequal distribution of higher education resources in the central and western regions compared to eastern and other regions, and thus, solving the problem of backwardness in higher education in the central and western regions.

In terms of foreign partners, besides the traditional educational developed countries such as the US and the UK, the relevant policies show that the countries involved in the BRI region are beginning to have a notable share in transnational higher education cooperation with China. In 2016, the Ministry of Education released the policy ‘Education Initiative of Promoting the Construction of the Belt and Road"(Hereinafter, referred to as ‘Education Initiative 2016’) (MoE Citation2016) clearly emphasises the role of Sino-foreign higher education cooperation in promoting ‘Education Initiative 2016’ in the BRI region. The education initiative on the BRI received much attention for China’s national and international development through which the central government’s intentions were elucidated: one is to expand higher education opening-up further for national development, and the other is to improve China’s international status, by boosting the quality of international education provision and encouraging more transnational partnerships in education cooperation with the support from institutions.

Finding 3: newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes between 2018 and 2020

Finding 3.1. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by subnational regions in China between 2018 and 2020

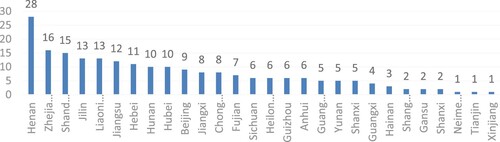

The data (see and ) show that there are altogether 215 new approved programmes, allocated among 28 provinces from six main regions. East China has the most number of new programmes with 66 cases in total, including Shanghai 2, Jiangsu 12, Zhejiang 16, Fujian 7, Shandong 15, Jiangxi 8 and Anhui 6, prospectively, taking up 30.7% of the total. The regions in Central China follow the second place with 48 new programmes, taking up 22.3% of the total, including Henan 28, Hunan 10 and Hubei 10 cases. The 33 newly approved joint programmes, making up 15.3% of the total, are spread among seven provinces and municipalities in West China, in the third position, including Xinjiang 1, Shanxi 5, Gansu 2, Sichuan 6, Yunnan 5, Chongqing 8 and Guizhou 6. Besides, the figure shows there are 32 new projects, taking up 14.9% of the total, approved by the Ministry of Education coming from universities in North-East China, including Jilin 13, Liaoning 13 and Heilongjiang province’s 6 new cases. While, the new approved programmes from the regions in North China (including Beijing 9, Tianjin1, Hebei11, Shanxi2 and Neimenggu1) and South China (Guangdong 5, Guangxi 4 and Hainan 3) take up 11.2% and 5.6% of the total, respectively.

Figure 1. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by subnational regions in China between 2018 and 2020. Data source: MoE (www.moe.gov.cn).

Table 3. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by subnational regions in China between 2018 and 2020.

The data clearly shows that besides the traditionally developed regions in Eastern China, the prevailing policies have signalled evolving geographic priorities to other intra-regions with respect to the establishment of new Sino-foreign joint programmes. The emerging regions in Central and Western China have been helped by the series of policies released during the period 2010–2020 including ‘National Outline 2010–2020’, ‘BRI 2013’, ‘Several Opinion 2016’, ‘The Acceleration 2018’, ‘The Key Work 2019’ and ‘China's Education Modernization 2035’. They have begun to host more newly approved joint programmes than other regions.

Finding 3.2. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by foreign providers between 2018 and 2020

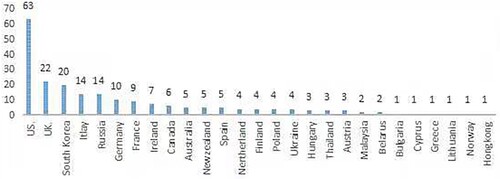

Together with the US and the UK, foreign providers from the BRI region are increasing. The data in shows that during the period 2018–2020, there were 27 countries involved as foreign providers in the Sino-foreign joint programmes, among which there were 11 countries from the BRI region.

Figure 2. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by foreign providers between 2018 and 2020’. Data source: MoE (www.moe.gov.cn).

The data show that traditional partners such as the US and the UK are still best represented, ranking in the first and second positions with 63 and 22 newly approved programmes each (39.5% of the total approved). Countries outside the BRI region, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and some Continental European countries, including Spain, Italy, France, Netherland, Finland, Austria, Norway, and Germany, contribute to 94 new approved programmes during the period, making up 43.8% of the total (see ).

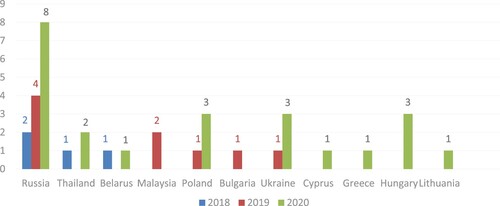

The countries from the BRI region account for 16.7% of the total Sino-foreign joint programmes with 36 programmes in total. Russia is in the leading position with 14 new programmes. In 2018, there were only three from the BRI region including Russia, Thailand and Belarus. However, the number of participants from the BRI region witnesses a great annual increase. In 2019, there are five from the BRI region, besides Russia, with the new participation of Malaysia, Poland, Bulgaria and Ukraine. In 2020, nine countries from the BRI region set up new joint programmes. Newly represented countries in the BRI region included Cyprus, Greece, Hungary and Lithuania (see ).

Figure 3. Distribution of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes by BRI region countries between 2018 and 2020. Data source: MoE (www.moe.gov.cn).

This supports the trend that more countries from the BRI region which are beyond the traditional set of foreign HE partner regions will become involved in Chinese TNHE cooperation, indicating a new role for geopolitical considerations in the setting up of new Sino-foreign partnerships.

Discussion

The findings above explicitly show the characteristics of these TNHE cooperation programmes in terms of regions in China and abroad. Overall, these demonstratethe MoE-approved 215 joint programmes altogether between 2018 and 2020, covering 29 mainland provinces and cities except Tibet and Ningxia province, with more Sino-foreign joint programmes concentrated in Central, East and West China with foreign partners like the US, UK, and notably, new partners from the countries in the BRI region. We assume that the pursuit of China’s prestige has been the driving force behind this TNHE development agenda. And this evolving regional distribution of Sino-foreign joint programmes by the central government offers considerable scope to explain how in China, the TNHE partnership is closely tied to the state and required to execute national policy directives to raise China’s international status which changed from that of a peripheral country to that of one approaching the core (Pan Citation2013).

Pan and Lo (Citation2017) highlight the trade and diplomatic linkages in foreign policies for repositioning China internationally with the interplays between China and other states in the Neo-tributary system. Thus, a Neo-tributary perspective can be used to identify how China engages with other polities to form favourable relationships and interprets the legacy of the tributary mentality and strategies, as manifested in China’s contemporary international engagements in geopolitical discourse. TNHE institutions have become one of the strategic instruments as knowledge diplomacy to establish China as a geopolitical powerhouse, and correspondingly, a new TNHE partnership configuration appears in China’s base.

The findings above demonstrate that a tributary mentality also influences recent Chinese geopolitical trends of TNHE partnership with endeavours at home and abroad. The discussion is developed based on the four analytic categories of the Neo-tributary framework (Pan and Lo Citation2017), by combing together Chinese exceptionalism; trade and diplomacy linkages; cultural assimilation; and image building from domestic and global perspectives.

Domestic perspective

Recent national and worldwide surveys of university internationalisation priorities and rationales show that establishing an international profile or global standing is becoming more important than reaching international ‘standards’ of excellence (Knight Citation2013). Therefore, TNHE cooperation plays an important role in national and regional developments with respect to the ‘profile development’. From a domestic perspective, in the pursuit of Chinese exceptionalism to recover the prestige under the tributary system, China formulates domestic regional development. The findings in this paper clearly show that more joint programmes are approved in central and western China, in addition to traditionally better developed eastern regions. Many scholars have explored the reasons behind this regional priority. Fang and Yu (Citation2020) argue that regions with their relatively sound urban systems and highly integrated economic sectors can effectively participate in even further global integration and competition to drive national economic development and finally achieve international prestige. Such policies discussed above as ‘Higher Education Revitalisation Plan 2012-2020’ (MoE Citation2010 ) explicitly indicates that East China, as one of the country’s most developed regions, not only takes the leading role in international cooperation with a wealth of education resources but is also encouraged to be a model for other regions. Thus, East China always pioneers new Sino-foreign joint programmes in the study period 2018–2020. Moreover, there is a significant gap between the capacity and the quality of higher education in the central and western parts of China. ‘Higher Education Revitalisation Plan 2012-2020’ (MoE Citation2010) clarifies that the number of students in higher education institutions in Central and Western China accounts for 65.5% of the whole country, but resources are scarce in these regions, lagging behind those of the eastern region. High-quality higher education resources are being proposed for the central and western regions to support the accelerated development of higher education in these regions. Therefore, in 2018–2020, the share of the new partnerships in central China and western China grew to a comparable scale as eastern China. For example, Henan province located in central China had the largest number of newly approved Sino-foreign joint programmes in 2018–2020.

Global perspective

By operating in a ‘world system’ and acknowledging historical patterns and hierarchies, China has skillfully used hierarchic relationships to strengthen itself by learning from more-developed countries and building partnerships with less-developed countries (Pan Citation2013). On the one hand, the findings that there are more TNHE partnerships coming from the leading countries such as the US and the UK with their high-ranking universities demonstrate China’s claim to be a new global status based on its expanding economic and diplomatic relations with more advanced countries, reflecting its priorities and willingness to align itself with (and belong to) the First World club (Pan Citation2013; Pan and Lo Citation2017). Moreover, on the other hand, alongside this continued pursuit of high value and high quality partnerships, after three decades of economic reforms and opening itself to the West, China is becoming an emerging economic giant with increasingly important geopolitical and economical as well as political and cultural force in the world (Jacques Citation2012).

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s BRI proposal aimed to restore China’s historical position in trade and cultural exchange in the Eurasian region. In implementing BRI policies, its connection with international cooperation in HE and S&T was established. Indeed, Chinese policies aimed at advancing China’s HE and S&T agendas have been developed in close connection with policies serving the broader economic and political goals of achieving China’s overall rejuvenation and making it a leading country in the world (d’Hooghe, Citation2021). What stands out in various policy documents and practices in this TNHE cooperation is the prominence given to the role of regions (Schneider Citation2021) to form favourable relationships to revive the prosperity of the historical New Silk region through the lens of knowledge diplomacy. Sino-foreign cooperation in running schools along the BRI region are highly encouraged. In terms of Sino-foreign joint programmes, as shown above, the number of foreign providers of joint programmes approved during the studied period from the BRI region has significantly increased.

According to Kang (Citation2010), one of the characteristics of the Chinese tributary system is that foreign states seeking relations with China need to adopt Chinese culture (e.g. China’s administrative system, architecture, philosophy, religion, literature, etc.) (Han Citation1992; Woodside Citation1988). Performing the rituals is a symbolic expression of the tributary’s respect (Li Citation2004), through which the tributary’s cultural assimilation could be achieved. While Sino-foreign joint institutes and programmes are jointly operated by Chinese universities and foreign partners, China’s MoE has ultimate authority over them. Foreign counterparts based in China need to accept Chinese governance and regulations models which are deeply rooted in Chinese culture, through which it may expand its cultural influence, economic collaborations and diplomatic relations (Zaharna, Hubbert, and Hartig Citation2014). This constitutes an important part of China’s diplomatic strategy and is in line with its larger political and economic agenda.

Concluding remarks

This research reveals how the new-tributary strategy underpins the regional strategy and highlighted the role of TNHE within it. By 2020, China’s Ministry of Education had signed a memorandum with eighteen provinces, mostly from western and central regions in China, which use the advantages of their geographical positions and local characteristics to co-build education activities in support of the BRI. Our findings and discussion lead us to expect that there will be more transnational education partnerships at universities from central, western and eastern China with the BRI region. This hypothesis has significant implications and offers insight for policymakers or university makers in institutions and countries that want to set up a TNHE partnership in China.

More broadly, the identification of these trends has the potential to widen the field’s understanding of TNHE practices. In 2019, the CPC Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the Vision for China’s Education Modernisation 2035 (hereinafter, referred to as ‘The Vision 2035’). ‘The Vision 2035’ plans strategically that China will achieve overall education modernisation by 2035 and become the educational power worldwide as a new hub of international higher education, aligning with the old-developed countries such as the US and the UK, by 2049. To achieve these targets, considering the unbalanced layout of the international partnerships where English-speaking countries share a larger share of international cooperation with China, the central government decentralises TNHE territorial politics with today’s Belt and Road Initiative by encouraging more TNHE partnership with the BRI region. We hope that this research will start a further discussion on the issues around China’s TNHE policy making and practices. In this research conclusion, China operates both globally and domestically (regionally) through TNHE to reach the foreign policy goal of the Chinese government and promote regional development at home. In the future, more in-depth research might explore the interaction between China’s domestic (regional) economic development policies and foreign policy objectives (and the BRI specifically), from a territorial political perspective.

Acknowledgements

We thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editors for helpful comments on the version originally submitted to the journal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ball, S. J. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” The Australian Journal of Education Studies 13 (2): 10–17.

- Christopherson, S., M. Gertler, and M. Gray. 2014. “Universities in Crisis.”

- Crouch, C., and P. Le Galès. 2012. “Cities as National Champions?” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (3): 405–419.

- d’Hooghe, I. 2021. “China’s BRI and International Cooperation in Higher Education and Research.” In Global Perspectives on China’s Belt and Road Initiative, edited by F. Schneider, 35–58. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Fairbank, J. K. 1983a. The United States and China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fairbank, J. K. 1983b. The United States and China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press in Pan, S. Y., and J. T. Y. Lo. 2017. “Re-conceptualizing China’s rise as a global power: a neo-tributary perspective.” The Pacific Review 30 (1): 1–25.

- Fang, C., and D. Yu. 2020. “The Spatial Pattern of Selecting and Developing China’s Urban Agglomerations.” In China’s Urban Agglomerations, 65–126. Singapore: Springer.

- Gibbs, G. R. 2014. “Using Software in Qualitative Analysis.” The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 277–294.

- Han, Y.-W. 1992. “The Establishment and Development of Nationalist History.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 5: 62–64.

- Herrschel, T., and P. Newman. 2017. Cities as International Actors. London: Springer. 978–971.

- ICEF. 2018. “China Announces the Closure of More Than 200 TNE programmes.” Accessed 12 January 2020. https://monitor.icef.com/2018/07/china-announces-closure-200-tne-programmes/#:~:text=The%20Chinese%20Ministry%20of%20Education,programmes%20and%20jointly%20managed%20institutions.&text=The%20MOE%20reports%20that%20roughly,the%20undergraduate%20level%20or%20above.

- Jacques, M. 2012. “A Point of View: What Kind of Superpower Could China Be?” BBC News Magazine, 19 October. Accessed 18 May 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19995218

- Jessop, B. 1990. State Theory: Putting the Capitalist State in its Place. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Jessop, B. 2008. “A Cultural Political Economy of Competitiveness and its Implications for Higher Education.” In The Knowledge Economy and Lifelong Learning, (pp. 57–83). Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

- Jonas, A. E. 2013. “City-Regionalism as a Contingent ‘Geopolitics of Capitalism’.” Geopolitics 18 (2): 284–298.

- Kang, D. C. 2010. East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Knight, J. 2013. “The Changing Landscape of Higher Education Internationalisation–for Better or Worse?” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 17 (3): 84–90.

- Knight, J., and E. T. Woldegiorgis. 2017. Regionalization of African Higher Education: Progress and Prospects. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Leskina, N., and E. Sabzalieva. 2021. “Constructing a Eurasian Higher Education Region: Points of Correspondence Between Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 62 (5-6): 716–744.

- Li, Y. 2004. Chaogong Zhidu Shilun [A Historical Review of the Tributary System]. Beijing: Xinhua Press.

- Lo, T. Y. J., and S. Pan. 2021. “The Internationalisation of China’s Higher Education: Soft Power with ‘Chinese Characteristics’.” Comparative Education 57 (2): 227–246.

- Metzgar, E. T. 2016. “Institutions of Higher Education as Public Diplomacy Tools: China-Based University Programs for the 21st Century.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (3): 223–241.

- Ministry of Education. 2010. Higher Education Revitalization Plan in the Central and West China 2012–2020. Accessed 14 January 2021. http://old.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s7056/201303/148468.html.

- Ministry of Education. 2016. Education Initiative of Promoting the Construction of the Belt and Road. Accessed 14 January 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A20/s7068/201608/t20160811_274679.html.

- Ministry of Education. 2019. The Key Work of the MOE 2019. Accessed 21 January 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201902/t20190222_370722.html.

- Ministry of Education. 2020. Acceleration of the Opening Up of Education in the New Era. Accessed 22 January 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/202006/t20200623_467784.html.

- Moir, E., T. Moonen, and G. Clark. 2014. What are Future Cities? Origins, Meanings and Uses. Government Office for Science 14.

- Moisio, S. 2018a. Geopolitics of the Knowledge-Based Economy, p. 194. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Moisio, S. 2018b. “Urbanizing the Nation-State? Notes on the Geopolitical Growth of Cities and City-Regions.” Urban Geography 39 (9): 1421–1424.

- Moisio, S., and A. E. Jonas. 2018. “City-Regions and City-Regionalism.” Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories.

- Mok, K. H. 2019. “Contesting Globalization and Rethinking International-Regional Collaborations: China’s Approach to Internationalization of Education.” In 5th Peking University-University of Wisconsin Workshop on Higher Education. Peking University (Vol. 25).

- Mok, K. H., W. Xiong, G. Ke, and J. O. W. Cheung. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on International Higher Education and Student Mobility: Student Perspectives from Mainland China and Hong Kong.” International Journal of Educational Research 105: 101718.

- Neubauer, D. 2012. “Higher Education Regionalization in Asia Pacific: Implications for Governance, Citizenship and University Transformation.” Asian Education and Development Studies 1 (1): 11–17.

- Pan, S. Y. 2013. “China’s Approach to the International Market for Higher Education Students: Strategies and Implications.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 35 (3): 249–263.

- Pan, Su-Yan, and Joe Tin-Yau Lo. 2017. “Re-Conceptualizing China’s Rise as a Global Power: A Neo-Tributary Perspective.” The Pacific Review 30 (1): 1–25.

- QAA. 2017. Country Report: The People’s Republic of China. Accessed 21 September 2019. www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/international/country-report-china-2017.pdf?sfvrsn=12c9f781_10.

- Ransom, J. 2018. “The City as a Focus for University Internationalisation: Four European Examples.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 48 (4): 665–669.

- Rizvi, F., and F. Lingard. 2010. Globalizing Education Policy. New York: Routledge.

- Schneider, F. 2021. Global Perspectives on China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Asserting Agency Through Regional Connectivity, p. 350. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Singh, A. 2020. “The Myth of ‘Debt-Trap Diplomacy’and Realities of Chinese Development Finance.” Third World Quarterly 42 (2): 239–253.

- State Council. 2010. National Outline for Mid and Long Term Education Planning and Development 2010–2020. Accessed 14 January 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A01/s7048/201007/t20100729_171904.html.

- State Council. 2014. The National New Urbanization Development Plan (2014–2020). Accessed 9 March 2021. available at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2014/0317/c1001-24649809.html.

- State Council. 2018. The Acceleration of the Implementation of the Education Modernization Program 2018–2022. Accessed 19 January 2021. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s6052/moe_838/201902/t20190223_370859.html.

- Wang, J. 2011. “China’s Search for a Grand Strategy: A Rising Great Power Finds its Way.” Foreign Affairs 90 (2): 68–79.

- Woodside, A. 1988. Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Nguyen and Ch’ing Civil Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard, MA: Council on East Asian Studies.

- Wu, H. 2019. “Three Dimensions of China’s “Outward-Oriented” Higher Education Internationalization.” Higher Education 77 (1): 81–96.

- Zaharna, R. S., J. Hubbert, and F. Hartig. 2014. Confucius Institutes and the Globalization of China’s Soft Power. Los Angeles, CA: Figueroa Press.