ABSTRACT

This article conceptualises and examines the notion of the ‘career rewind’ that highly skilled refugees experience after arrival in a receiving country; in this case Sweden. Rather than a career interruption, career hiatus or deferred progression, this article argues that a career rewind takes place. The rewind entails, among other things, re-taking courses, re-acquiring professional knowledge and skills, and recertification in the case of registered professions. The empirical material was collected in 20 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with pharmacists with a refugee background in Sweden. The findings provide insights into pharmacists’ experiences of a career rewind in different places, and their attempts to ‘unwind’ the rewind.

Introduction

It is generally expected that persons with tertiary degrees ‘move up’ in their careers when they gain new knowledge, skills, and experience in their professions. For forced migrants, however, this ‘forward and upward’ trajectory tends to be reversed when they are uprooted from their careers. This article examines the professional trajectories of persons in Sweden who have been granted refugee status under the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. They have completed a tertiary degree or have the equivalent in experience (Iredale Citation2001). While many highly skilled refugees plan to return to their professions after arrival in a receiving country (Davey and Jones Citation2019), they often experience deskilling and underemployment (OECD Citation2016).

This article conceptualises and examines highly skilled refugees’ ‘career rewind’ after arrival in a receiving country like Sweden. The rewind entails demotivation, a loss of professional status and deskilling, as well as a process of re-learning, re-acquiring professional knowledge and skills, and recertification in order to re-enter one’s profession in a receiving country. The article argues that the career rewind entails more than a career disruption (Borselli and van Meijl Citation2021; Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021) or rupture (Bygnes Citation2021), as the literature tends to describe the career re-entry process. It is in fact a rewind of one’s professional status, knowledge, and skills. I explore the personal and geographical aspects of the career rewind, and how these factors shape the professional re-entry process for highly skilled refugees.

The career rewind is most pronounced in professions that require a license to practice (i.e. registered professions), including medical and teaching professions. Registered professions are governed by laws, regulations, and authorisation requirements that aim to ensure the public’s safety and a high standard of practice. These requirements may include proficiency in the host country’s language, the completion of a proficiency test or a complimentary programme, and on-the-job training. By focusing on the strategies of highly skilled refugees to re-enter their professions in their new home country, this article aims to provide a nuanced counter-narrative to riches-to-rags narratives (Bygnes Citation2021).

In this paper I focus on pharmacists, who are in high demand in Sweden. A shortage of pharmacists emerged in Sweden when the monopoly of state-owned pharmacies was opened up to private actors in 2009–2010 (Bergman, Granlund, and Rudholm Citation2016; Wisell, Winblad, and Sporrong Citation2015). The number of pharmacies increased, opening hours were extended, and a new law stipulated that a pharmacist had to be onsite during opening hours. These factors in turn contributed to an increase in demand for pharmacists. The personnel shortage was exacerbated by an increase in retirements and a limited number of seats in pharmacist training programmes (Swedish Pharmacy Association Citation2021). Foreign-born pharmacists could alleviate the shortage, but they have to obtain a license from the National Board of Health and Welfare to practice their profession in Sweden.

The study focuses on Sweden for two reasons. First, Sweden received a high number of asylum seekers between 2011 and 2015, and the country even hosted the highest number of asylum seekers per capita of any European state between 2009 and 2015 (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). The majority of applicants have now been granted residence permits and are studying, looking for work, or working in Sweden. Second, the Swedish government funds complimentary programmes and fast-tracks that aim to speed up migrants’ re-entry into professions with labour shortages (Barane and Mattsson Citation2017; Economou Citation2021). Despite these initiatives, it takes highly skilled refugees a long time to find employment in their field of expertise – if at all (Vogiazides, Bengtsson, and Axelsson Citation2021).

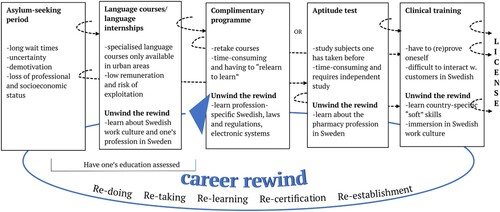

The article addresses the following research questions: What constitutes the career rewind? How do highly skilled refugees experience the career rewind? And how do they ‘unwind’ the career rewind over time? To answer these questions, I examine four ‘steps’ in the career trajectories of highly skilled refugees in registered professions; namely the asylum-seeking period, Swedish language courses and language internships, proficiency tests and complimentary programmes, and clinical training. In these professional trajectories, highly skilled refugees ‘re-do’ and re-learn their professions. At the same time, these programmes provide highly skilled refugees with new country-specific, as well as culturally-specific knowledge and skills, that may help them ‘unwind’ the career rewind.

Conceptualising the career rewind

Compared to labour migrants and family reunification migrants, highly skilled refugees are the most disadvantaged when they arrive in a receiving country. Their forced migration backgrounds have an impact on their resources and choices for re-entering their professions (Piętka-Nykaza Citation2015). Refugees left their homes involuntarily, often lacking time to prepare for their personal and professional lives in a receiving country. They may also have experienced traumatic stress before, during, and/or after flight. These factors combined pose obstacles to employment (Gericke et al. Citation2018).

The career rewind can be conceptualised as one that occurs in various ‘steps’ of refugees’ professional trajectories; from the asylum-seeking period to re-entry into one’s profession and socialisation in the workplace. The ‘steps’ terminology, however, may give the false impression that refugees follow a linear, unidirectional and chronological career trajectory (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021; Willott and Stevenson Citation2013). In fact, highly skilled refugees experience a sudden break in their career trajectories, and they are often forced to rethink these. The rupture reshapes their ‘ … conceptions of personal career time, from being linear, cumulative or simply stable to being uncertain and fragmented’ (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021, 63), and the pathway for re-entry can be experienced as ‘moving back rather than forward’ (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021, 60).

Highly skilled refugees’ re-entry process into the labour market can be affected by emotional and/or physical trauma, caring responsibilities, extended waiting times, insecure legal status, missing paperwork, devaluation of formal qualifications, language barriers and cultural differences, a lack of information about education opportunities and authorisation requirements, a limited professional network in the receiving country, and discrimination by employers (Bucken-Knapp, Fakih, and Spehar Citation2019; Butt et al. Citation2019; Campion Citation2018; Carlbaum Citation2021; Wehrle et al. Citation2018). These factors contribute to the career rewind. Highly skilled refugees also lose their professional and socio-economic status when their professional qualifications are not recognised in the receiving country (Davey and Jones Citation2019; Willott and Stevenson Citation2013). In a study of refugees in medical and teaching professions in the UK, Davey and Jones (Citation2019) found that the loss of professional identity can result in depression, anxiety, and a decline in self-esteem and confidence. At the same time, they argue that the process of professional requalification enables refugees to reclaim their professional identity and self-worth.

Long wait times can exacerbate the career rewind, as the wait itself and insecurity about the outcome can be stressful and demotivating. Forced migrants experience a ‘trajectory of waiting’ during the asylum-seeking period, which can include waiting for housing, education and training, family reunification, marriage, and employment (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021). These waiting periods can prompt some highly skilled refugees to rethink their life plans and pursue alternate careers (Mozetič Citation2021). While acknowledging the detrimental effects of uncertainty and insecure legal status, Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish (Citation2021) note that asylum seekers can be ‘active in waiting’ by engaging in volunteering, teaching, language learning, and sports (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021). They argue that these activities can help them imagine a future.

Career reclaiming strategies differ by refugees’ gender, family status, age, region of origin and other personal characteristics. Young, single males tend to set long-term educational and professional goals, while refugees with families focus on providing for their dependents and creating a good future for their children (Borselli and van Meijl Citation2021). Persons who aim to reunify with spouses or relatives tend to be most concerned about their legal status, whereas the priority of these factors can change over time as personal and/or structural constraints change (Borselli and van Meijl Citation2021). Re-entry into the profession is also affected by a person’s country of origin, language proficiency, the time that has passed since the person last practiced the profession (Ong et al. Citation2010), as well as career stage (Piętka-Nykaza Citation2015).

Materials and methods

The author conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 20 pharmacists with a refugee background in Sweden. The interviews were conducted between January 2020 and January 2022, using in-person data gathering tools until March 2020, then virtual communication (Zoom) due to COVID-19-related restrictions. The interviews, which lasted approximately one hour each, addressed informants’ professional trajectories and their experiences with re-entering their professions. The author established contact with three informants while conducting classroom observations in a complimentary programme (kompletteringsutbildning) for pharmacists. The remaining informants were identified in Internet searches and through LinkedIn. Eighteen interviews were conducted in Swedish and two in English, based on the language preference of informants. All informants had lived in Sweden for at least six years and spoke Swedish fluently. provides information about the informants. The table includes pseudonyms and does not provide information about country of origin to protect the identities of the informants. Sixteen informants were born in Syria, two in Egypt, one in Iran, and one in Iraq.

Table 1. Study informants.

The author conducted the data analysis in two stages (Cope Citation2010). First, the author coded notes from all 20 interviews in NVivo 12, using codes based on the literature review and creating ‘in vivo’ codes while reading the interview notes. The author coded statements related to professional trajectories and experiences with re-entering the pharmacy profession. These first-level codes were refined during the coding process. The analysis identified re-learning and re-doing, loss of professional status and the necessity to prove oneself as key elements in the career geographies of pharmacists with a refugee background. In the second stage, the author developed the concept of the ‘career rewind’. The author re-read the interview notes to examine how informants described these experiences, transcribed sections of interviews that discussed the career rewind experience, and re-coded these segments. Thereafter, the author grouped codes into larger themes that are presented in the next section.

Permission was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019-05330) to collect the empirical data that is reported in the article. All participants received written information about the study at the start of an interview, were informed about the purpose of the study and their rights to withdraw, and were asked if they had any questions. After the researcher had answered the questions, the participants gave verbal consent to participate in the interview. Interviews were only recorded when a participant consented to do so.

Refugees’ experiences of the career rewind in Sweden

In Sweden, pharmacists are a licensed profession, regulated by the National Board of Health and Welfare. To practice as a pharmacist, a person needs to obtain a license from the Board. In 2016, the Board introduced new licensing requirements for pharmacists who had completed their degree outside the EU/EEA. The Board introduced two options for authorisation: a proficiency test and a complimentary programme. The proficiency test consists of a theoretical test on 22 subjects and a practical test, both administered in Swedish. After passing both tests, a person has to take a course in Swedish laws and regulations and to arrange for 6 months of clinical training (National Board of Health and Welfare Citation2022). It usually takes 2–4 years to complete the authorisation process (National Board of Health and Welfare Citation2022).

Alternatively, a person can apply for a complimentary programme offered by Uppsala University or the University of Gothenburg. The programme consists of one semester of profession-specific language training (required since autumn 2022), one semester of theoretical courses, followed by six months of clinical training in a pharmacy. Upon completion of these parts, a person can apply for a license to practice. In order to be admitted to a complimentary programme, one needs to have completed a pharmacist education outside the EU/EEA that is equivalent to a 5-year Swedish education in pharmacy. One also has to have attained language proficiency levels Swedish 3 and English 6 (Uppsala University Citation2022). This means that most informants had to study Swedish and English after their arrival in Sweden to meet university admission requirements. Applicants who have worked in Sweden or completed an internship in a Swedish pharmacy are awarded extra admission points.

Most courses are offered online, enabling students to participate from anywhere in Sweden. Students come to campus to take some in-person classes and exams. The course period is followed by six months of clinical training (reduced to five months if a person has gained work experience as a personal care advisor or technician in a pharmacy in Sweden), arranged by an internship coordinator. Upon completion of the programme, one can apply for authorisation from the National Board of Health and Welfare.

This section presents insights into the lived experiences of pharmacists with a refugee background in Sweden. It shows how the asylum-seeking period, Swedish language courses and language internships, proficiency tests and complimentary programmes, and clinical training shaped informants’ professional trajectories, and the ways in which they tried to ‘unwind’ the career rewind in different geographical contexts. The aspects of the career rewind and its ‘unwinding’ are shown in .

Figure 1. The career rewind for highly skilled refugees in registered professions. The dotted arrows show that the careers of highly skilled refugees do not follow a linear, unidirectional and chronological trajectory. For example, one can take the aptitude test before showing proof of Swedish language competency.

The asylum-seeking period

For all informants, the asylum-seeking period was marked by a time of waiting, uncertainty, and stress. Upon arrival they wanted to re-enter their profession as quickly as possible, but they became demotivated by waiting and by the uncertainty about the decision on their asylum claim. Mariam explains what the wait time was like during the asylum-seeking period and thereafter:

There is nothing to do. You just have to wait [laughs a little]. That is how it is here in Sweden. Everything is very slow. We come from other countries, we like it when, we want everything to go as fast as possible. … Everything takes a very long time. You have to be patient and wait when nothing happens, there is nothing you can do. (Pharmacist 14)

Swedish language courses

All registered medical professions in Sweden require proficiency in Swedish. Asylum seekers can take basic language training while they are waiting for a decision on their application. They qualify for Swedish from Day One, a government-funded language programme offered by folk high schools and study associations (studieförbund). The programme teaches basic Swedish language and provides information about Swedish society (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2020). They can also attend study circles offered by non-profit organisations and volunteers, and study Swedish on their own. Asylum seekers do not, however, qualify for regular state-funded language courses.

When an asylum seeker has been granted a residence permit, the person can enrol in a two-year establishment programme run by the local Public Employment Service. Together with an employment officer, the programme participant creates a two-year individualised establishment plan. The plan usually contains government-funded Swedish for Immigrants courses, a course about Swedish society, democracy, rights and obligations, and labour market preparation activities (Swedish Public Employment Service Citation2019). Large cities offer profession-specific language courses and fast-paced courses for persons with an academic background. Smaller municipalities do not offer these specialised courses and may have a long waitlist. The differences in course offerings and wait times show a clear geography to the career rewind that can be explained by the high spatial concentration of knowledge and power in urban areas (Meusburger Citation2000).

The availability of language training depends on the place of residence. For example, Ghassan wanted to take an intensive advanced language course in a nearby town. The request was denied as the Municipality where he resided offered a (lower-level) language course. Ghassan was delayed in his language training, and ultimately, his admission into the complimentary programme. Abdel and Seth also lived in small municipalities and had to wait to enrol in available language courses. They were dissatisfied with the slow pace and quality of the courses, similar to the findings of Bucken-Knapp, Fakih, and Spehar (Citation2019).

Abdel noted that bigger cities offer Swedish for Academics, profession-specific language courses and intensive courses for Swedish for Immigrants, providing a faster route into the labour market. But he also saw an advantage of living in smaller places after finishing the complimentary programme: ‘Small towns need us more than big towns. If you go to Stockholm it is not easy to find a job’ (Pharmacist 3). This was seconded by Khalil: ‘It is difficult to compete in the Swedish market, especially in large cities. When we compete with Swedes, we lose, unfortunately. … We have no chance, they win. Because of the language, because of education. … I accept it’ (Pharmacist 1).

Language internships

In order to acquire profession-specific Swedish language skills, participants in the establishment programme can arrange for a language internship in a workplace. If accepted, they spend approximately 20 hours a week on the internship and 20 hours on formal language training. Language internships aim to help refugees learn professional vocabulary, become familiar with Swedish working culture, and learn about their profession in Sweden (Alaraj et al. Citation2019). If an employer agrees to offer an internship, the employer signs an agreement with the Swedish Public Employment Service. Language internships last for approximately three months and can be renewed.

It takes considerable time and effort to arrange a language internship, especially in large cities. Khalil explains his search strategy:

Micheline: How did you find your language internship?

Khalil: By myself, by myself. I printed out my CV and travelled by [public transport in the city where he lives]. When I see a sign that says ‘pharmacy’ I get off and drop off my CV. I dropped off 20–25 in one day alone. … So I was enthusiastic to start working in Sweden. … I did my best and went from one pharmacy to another. After a while I was offered [an] internship. (Pharmacist 1)

Seth, who now also lives in a large city, sent approximately twenty emails to pharmacy managers. Two managers with refugee background invited him for an interview, and one of them offered him an internship. The hiring manager remarked ‘I know what it is like [to be a pharmacist with a refugee background in Sweden], I want to help out’. Aisha found an internship through her teacher for Swedish for Immigrants. The teacher, who came from Bosnia, said ‘We have the same destiny. We have both experienced war’. While research has noted that a lack of professional networks in a receiving country is a key barrier to employment (e.g. Campion Citation2018), in these cases the shared refugee background helped secure an internship.

The experiences of Khalil and Seth show that refugees need to be proactive to create opportunities for themselves. In a study of Syrian and Afghan refugees in Austria, Eggenhofer-Rehart et al. (Citation2018) noted that being proactive helps refugees learn the language, culture, and institutional context of the receiving country, find information about training opportunities, and establish connections with locals (Citation2018). These endeavours can contribute to personal growth as refugees become more confident, mentally stronger, and more resilient (Wehrle et al. Citation2018). The experience of the career rewind, however, can drain refugees’ energy and ability to be proactive.

Overall, informants who had secured a language internship found it useful. It provided an opportunity to learn profession-specific Swedish language in a work setting and to observe workplace norms and behaviours. In addition, being in a pharmacy environment enabled the informants to regain their professional identity (Piętka-Nykaza Citation2015). Salim read information on the packaging of medications while stocking shelves, and thereby learned the names and usage of medications that he was unfamiliar with. In addition, interns learned how a Swedish pharmacy works.

However, three interns were dissatisfied. Farid and Karim had little interaction with their colleagues and customers. Ghassan’s manager asked him to do the vacuum cleaning and lift heavy boxes (he lifted an imaginary box on Zoom to illustrate the task). Karim’s manager wanted him to work weekends which was not a requirement of an internship. Farid noted that ‘we are free labour. … we are extra hands for them [employers]’. Karim explained the situation as ‘you don’t know the language. You don’t know your rights. They [employers] can take advantage of you’.

Ghassan had worked as a manager for an international pharmaceutical company before coming to Sweden. He felt that the tasks that he was asked to perform were below his expertise:

I became irritated. I have long experience as a manager, it is not easy. I had to stock shelves, arrange items on the shelf, take inventory. … I just worked with merchandise, it was not easy. (Pharmacist 10)

The low remuneration exacerbated informants’ frustration. In 2022, a refugee enrolled in the establishment programme was paid 308 Swedish crowns a day (approximately 30 euros) (Försäkringskassan [Social Insurance Agency] Citation2022), which can be supplemented with a housing benefit and a child benefit. Some informants contrasted their financial situation in Sweden with their lives before flight: ‘We had a luxury life in Syria. We had to start from the beginning in Sweden’ (Pharmacist 13) and ‘. … you had a clinic, your own job. You had respect in society’ (Pharmacist 15). In order to earn more money, some informants tried to secure an hourly-paid position after completing the internship. Khalil described his efforts as follows:

I found a [language] internship in a pharmacy. I did an internship for three months, and then they said to me ‘if you want to renew the internship you are welcome to do so.’ I asked if I could get some hours as a real job. I was a new arrival and I needed some income. They said to me, you need a little more training and practice a bit more. So I renewed my internship for three months. On the last day, they said ‘if you want to renew [your internship] that’s fine but we can’t give you a job. You are welcome [to continue] as an intern.’ I moved to another pharmacy and they did the same thing. After three months they said to me you are welcome [to continue] as an intern but no job. So, in total it was nine months without an income. (Pharmacist 1)

Proficiency test (kunskapsprov)

The proficiency test – if passed – is the fastest route to authorisation. In 2016, when several informants were studying for the proficiency test, the National Board of Health and Welfare decided to restructure the test to ensure patient safety. While the ‘old’ test covered only a few subjects and did not require a practical test, the Board was developing a more stringent test to ensure that pharmacists with a non-EEA/EU degree met national authorisation requirements. Aminah was admitted to the first group that took the new proficiency test in 2016. She had to wait six months for the new test to be implemented while the old test was discontinued: ‘It was very frustrating, there was no information about the proficiency test. We had to study without assistance’ (Pharmacist 12). When the new test was announced, she decided to cut off all social interaction with her friends and study full-time for two months:

I put all my effort into that proficiency test. It is very difficult to get into a new country where one does not have a job, where one does not know the language, one wants to do everything one can to get into the labour market and into Swedish society. So I thought ‘now it’s my time. Now I have to make it.’ But it were two tough, very, very difficult months for me. (Pharmacist 12)

I have taken the proficiency test. It was difficult. Very difficult. … There were more than 20 subjects. … A lot of subjects that one studies for by oneself and the questions are about everything, not just about some subjects, one has to read everything. … It is very difficult, you cannot ask anyone [for help]. (Pharmacist 14)

Complimentary programmes

In the six months of course work in the complimentary programme, students take courses in subjects that they had already taken in their degree programmes, as well as new subjects. Some informants had completed their coursework more than twenty years ago and had forgotten some of the material. In addition, they had to ‘relearn to learn’ as they had been out of school for a long time. Hassan describes what that is like:

New medications, new knowledge, we took courses in pharmacology, pharmacotherapy, we took 6–7 subjects. One does a refresher [he used the English word while speaking Swedish], one gets going, one becomes like a new student. … It is stressful, very stressful to study the complimentary education, you sit and study at least 8 to 12 hours per day, to pass the subjects. But later you thank, you say, they were right. They have the right program (Pharmacist 5)

It is also difficult to study at my age. I have to repeat [information] always to remember. You study in a different language, not in my language. In fact, much information disappeared from my memory. To add it to the memory takes time. There are many things they give us to study. There are also many new words, names for illnesses, you have to learn those to continue working in the profession. So that is very difficult for me. (Pharmacist 2)

Clinical training

After six months of theoretical courses, students take clinical training for five or six months. During this time, a supervisor in a pharmacy provides training and oversees the student’s progress. Reza, a supervisor, describes the students’ experiences at the beginning of the training:

Students are scared to interact with customers. They think that that is difficult. When one crosses the threshold, the, we say, the red line, you get started. I had a student, I was on vacation. When I came back she had only stocked shelves. My colleague said that he stood next to her [to interact with customers] but she was scared that she would make a mistake. The first day I came back I said ‘no, you have to take a customer.’ She felt very good afterwards. …

Micheline: Who calls it the red line? That is interesting.

Reza: I call it the red line [laughs a little]. (Pharmacist 19)

They [the teachers in the complimentary programme] were talking about ethics and power. Because when you wear a white coat [in a pharmacy], you’re already intimidating to the person [customer], so you can be, you can be assertive, but you can’t be too controlling. But you also can’t be too submissive. They were saying that you inform the patient, for example, of what they need to do, but without giving an order. You’re just stating what’s the fact and then it’s up to them to decide. … But that is a very useful skill, because I have noticed also in my job that Swedes are not very direct. They don’t say directly like, you know, I want you to do this or should be doing that, but it’s kind of a roundabout way. And sometimes I almost misunderstand that they are asking me to do something. It sounds more like a question to me [laughs]. (Pharmacist 8)

Discussion and conclusion

The narratives in this article provide insights into what I have called a ‘career rewind’ that highly skilled refugees experience. While each narrative is unique, in that they are shaped by personal, cultural, and institutional factors, they share certain commonalities. All informants experienced a career rewind, including the performance of low-level tasks during language internships, re-studying for the proficiency test or re-taking courses in the complimentary programme, and having to prove one’s knowledge and expertise to pass tests and obtain a license to practice. This process of re-doing, re-taking, and re-establishment was particularly difficult for informants who had long work experience before coming to Sweden.

While the career rewind was frustrating and at times exhausting, it did provide an opportunity for informants to acquire country-specific knowledge and skills. On a positive note, they observed how the pharmacy profession works in Sweden, and they learned the rules and regulations that govern the profession. They became proficient in Swedish, acquired country-specific cultural competence, and better understood Swedish social norms and behaviours. In addition, the retraining process helped them regain their professional status and self-esteem (Davey and Jones Citation2019).

The regaining of self-esteem was evident in informants’ narration of their professional trajectories. They generally described the asylum-seeking period as ‘lost time’ when they could not practice their profession. Similarly, some informants experienced the language internship as demotivating and frustrating, as they were not allowed to fill prescriptions or perform other profession-specific tasks. The narratives became more forward-looking when they discussed the aptitude test and complimentary programme. While acknowledging the difficulties in both pathways, it gave the informants a sense of purpose (Cangià, Davoine, and Tashtish Citation2021). The time spent in Sweden enabled the informants to gather information about recognition requirements and upskilling opportunities, and it gave them an opportunity to adapt to the professional environment (Piętka-Nykaza Citation2015).

It is, however, important to note that all informants in this study had the physical and mental ability to re-establish their careers in Sweden. They secured a language internship, inquired about profession-specific or fast-paced language courses, studied for the proficiency test or exams in the complimentary programme, and participated in clinical training. Thus, they were proactive in re-establishing their professional journey (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al. Citation2018). However, some informants mentioned friends or family members who were not able to re-enter the profession due to personal and/or structural challenges.

Geography plays a distinct role in the professional trajectories of highly skilled refugees (van Riemsdijk and Axelsson Citation2021). In this study, pharmacists in small municipalities had fewer options for taking language courses, and they did not have access to profession-specific or accelerated language courses that are offered in larger cities. The difference in access was diminished in the complimentary programmes, as the bulk of the courses were taught online. Geography also played a role in employment opportunities after certification. It is easier to find a (permanent) position in a pharmacy in smaller municipalities, where pharmacist shortages are most pronounced (Swedish Pharmacy Association Citation2021).

The rewind is particularly pronounced in registered professions that require a license to practice and proficiency in the host country’s language. The findings indicate that highly skilled refugees experience a career rewind despite their educational background and professional experience, as well as government-funded initiatives that aim to speed up their labour market re-entry. Over time, highly skilled refugees ‘unwind’ the career rewind by learning country-specific professional norms and values, as well as soft skills. However, it is important to note that the career rewind has a distinct geography, which means that the opportunities and challenges for retraining and obtaining a permanent position vary not only by gender, age, and family status but also quite profoundly by place of residence, especially whether refugees live in large urban areas or smaller rural places.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all research participants for discussing their professional trajectories. The author also thanks Heike Jöns for helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alaraj, Hala, Majsa Allelin, Matilda Amundsen Bergström, and Camilla Brudin Borg. 2019. “Internship as a Mean for Integration. A Critical Study.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 20 (2): 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0610-0.

- Barane, Anders, and Elsa Mattsson. 2017. Lägesrapport om snabbspår och att ta tillvara nyanländas kompetens [Report about fast-track programs and how to use the competence of refugees]. Stockholm: Sveriges kommuner och landsting.

- Bergman, Mats A, David Granlund, and Niklas Rudholm. 2016. “Reforming the Swedish Pharmaceuticals Market: Consequences for Costs per Defined Daily Dose.” International Journal of Health Economics and Management 16 (3): 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-016-9186-4.

- Borselli, Marco, and Toon van Meijl. 2021. “Linking Migration Aspirations to Integration Prospects: The Experience of Syrian Refugees in Sweden.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa043.

- Bucken-Knapp, Gregg, Zainab Fakih, and Andrea Spehar. 2019. “Talking About Integration: The Voices of Syrian Refugees Taking Part in Introduction Programmes for Integration Into Swedish Society.” International Migration 57 (2): 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12440.

- Butt, Mohsin Faysal, Louise Salmon, Fahira Mulamehic, Avelyn Hixon, Abdul Rehman Moodambail, and Sandy Gupta. 2019. “Integrating Refugee Healthcare Professionals in the UK National Health Service: Experience from a Multi-Agency Collaboration.” Advances in Medical Education and Practice Volume 10: 891. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S213543.

- Bygnes, Susanne. 2021. “Not All Syrian Doctors Become Taxi Drivers: Stagnation and Continuity Among Highly Educated Syrians in Norway.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 22 (1): 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00717-5.

- Campion, Emily D. 2018. “The Career Adaptive Refugee: Exploring the Structural and Personal Barriers to Refugee Resettlement.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.008.

- Cangià, Flavia, Eric Davoine, and Sima Tashtish. 2021. “(Im) Mobilities, Waiting and Professional Aspirations: The Career Lives of Highly Skilled Syrian Refugees in Switzerland.” Geoforum 125: 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.06.015.

- Carlbaum, Sara. 2021. “Temporality and Space in Highly Skilled Migrants’ Experiences of Education and Work in the Rural North of Sweden.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 40 (5-6): 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2021.1984325.

- Cope, Meghan. 2010. “Coding Qualitative Data.” In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, edited by Iain Hay, 281–294. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Davey, Kate Mackenzie, and Catherine Jones. 2019. “Refugees’ Narratives of Career Barriers and Professional Identity.” Career Development International 25 (1): 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2018-0315.

- Dustmann, Christian, Francesco Fasani, Tommaso Frattini, Luigi Minale, and Uta Schönberg. 2017. “On the Economics and Politics of Refugee Migration.” Economic Policy 32 (91): 497–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eix008.

- Economou, Catarina. 2021. “A Fast Track Course for Newly Arrived Immigrant Teachers in Sweden.” Teaching Education 32 (2): 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2019.1696294.

- Eggenhofer-Rehart, Petra M, Markus Latzke, Katharina Pernkopf, Dominik Zellhofer, Wolfgang Mayrhofer, and Johannes Steyrer. 2018. “Refugees’ Career Capital Welcome? Afghan and Syrian Refugee job Seekers in Austria.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.004.

- Försäkringskassan [Social Insurance Agency]. “Om du deltar i etableringsprogrammet hos Arbetsförmedlingen” [If you participate in the establishment program of the Swedish Public Employment Service]. Accessed March 27 2022. https://www.forsakringskassan.se/privatpers/arbetssokande/om-du-deltar-i-etableringsprogrammet-hos-arbetsformedlingen.

- Gericke, Dina, Anne Burmeister, Jil Löwe, Jürgen Deller, and Leena Pundt. 2018. “How do Refugees use Their Social Capital for Successful Labor Market Integration? An Exploratory Analysis in Germany.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.12.002.

- Iredale, R. 2001. “The Migration of Professionals: Theories and Typologies.” International Migration 39 (5): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00169.

- Meusburger, Peter. 2000. “The Spatial Concentration of Knowledge: Some Theoretical Considerations.” Erdkunde 54 (4): 352–364. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2000.04.05.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2020. “High interest for Swedish from Day One” [Stort intresse för Svenska från dag ett]. Accessed April 8 2020. https://www.regeringen.se/artiklar/2016/11/stort-intresse-for-svenska-fran-dag-ett/.

- Mozetič, Katarina. 2021. “Cartographers of Their Futures: The Formation of Occupational Aspirations of Highly Educated Refugees in Malmö and Munich.” International Migration 59 (4): 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12799.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. 2022. “Obtaining a licence if you are educated outside EU and EEA.” Accessed March 3 2022. https://legitimation.socialstyrelsen.se/en/licence-application/outside-eu-eea/pharmacist-educated-outside-eu-eea/.

- OECD. 2016. How are Refugees Faring on the Labour Market in Europe? Paris: OECD.

- Ong, Yong Lock, Penny Trafford, Elisabeth Paice, and Neil Jackson. 2010. “Investing in Learning and Training Refugee Doctors.” The Clinical Teacher 7 (2): 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00366.x.

- Piętka-Nykaza, Emilia. 2015. “‘I Want to Do Anything Which Is Decent and Relates to My Profession’: Refugee Doctors’ and Teachers’ Strategies of Re-Entering Their Professions in the UK.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (4): 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fev008.

- Psoinos, Maria. 2007. “Exploring Highly Educated Refugees’ Potential as Knowledge Workers in Contemporary Britain.” Equal Opportunities International 26 (8): 834–852. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150710836163.

- Swedish Migration Agency. 2023. “Working while You are an Asylum Seeker.” Accessed July 4 2023. https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/Private-individuals/Protection-and-asylum-in-Sweden/While-you-are-waiting-for-a-decision/Working.html.

- Swedish Pharmacy Association. 2021. Annual Report. Stockholm. http://www.sverigesapoteksforening.se/wpcontent/uploads/2021/05/2021-Annual-Report-1.pdf.

- Swedish Public Employment Service. 2019. “The Establishment Programme.” Accessed September 20 2019. https://arbetsformedlingen.se/other-languages/english-engelska/stod-och-ersattning/att-delta-i-program/etableringsprogrammet.

- Uppsala University. 2022. “Kompletteringsutbildning för apotekare med utländsk utbildning” [Complimentary program for pharmacists with foreign education]. Accessed May 22 2022. https://www.uu.se/utbildning/ny-i-sverige-vill-studera/arbeta-som-farmaceut-i-sverige/kompletteringsutbildning-farmaceuter/.

- van Riemsdijk, Micheline, and Linn Axelsson. 2021. “Introduction to Special Issue: Labour Market Integration of Highly Skilled Refugees in Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands.” International Migration 59 (4): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12883.

- Vogiazides, Louisa, Henrik Bengtsson, and Linn Axelsson. 2021. Geographies of Occupational (mis) Match: The Case of Highly Educated Refugees and Family Migrants in Sweden. Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University.

- Wehrle, Katja, Ute-Christine Klehe, Mari Kira, and Jelena Zikic. 2018. “Can I Come as I am? Refugees’ Vocational Identity Threats, Coping, and Growth.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.010.

- Willott, John, and Jacqueline Stevenson. 2013. “Attitudes to Employment of Professionally Qualified Refugees in the United Kingdom.” International Migration 51 (5): 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12038.

- Wisell, Kristin, Ulrika Winblad, and Sofia Kälvemark Sporrong. 2015. “Reregulation of the Swedish Pharmacy Sector—A Qualitative Content Analysis of the Political Rationale.” Health Policy 119 (5): 648–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.03.009.