ABSTRACT

Global citizenship education (GCE) has been placed as a target within UNESCO’s SDG 4 – Quality Education, and although GCE and education for sustainable development (ESD) are highly interlinked, a detailed interpretation of what this means in a formal educational setting is limited. It can be argued character education (CE) could be one of the mediums to provide students with the appropriate skills for a sustainable future, as CE involves developing moral values to allow individuals to feel responsible for creating an equitable future for society. Countries in the GCC are developing new long-term development plans and reforms to align with the Sustainable Development Goals, including education. Thus, this paper examines the best methods for implementing a role-modelling character education programme in Saudi Arabia to help nurture children and young adolescents’ moral values, considering the Islamic cultural and pedagogical context in the region. This is based on the findings from a qualitative study that used 14 interviews and three focus groups with 17 participants, including parents, students, consultants, and teachers.

Introduction

Following Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the youth are encouraged to have global skills and knowledge making them sustainably conscious citizens. One of the targets of the SDGs, Target 4.7, emphasises the importance of global citizenship for learners to develop a sense of connectedness and responsibility with the world and its future, including cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioural elements (UNESCO Citation2018). However, how these skills are developed and what they involve are limited. The following paper presents character education as a medium to provide students with the appropriate skills for a sustainable future (Asif Citation2020), since character education is a method of teaching and learning that helps develop moral values to create responsible and caring individuals who can make a positive contribution to society. Using a somewhat generic specification, character can broadly be defined as ‘an individual’s set of psychological characteristics that affect that person’s ability and inclination to function morally’ (Berkowitz Citation2002, 48). The following study was conducted within the Islamic country of Saudi Arabia and therefore explores how character education can be developed within that sociocultural context. Islamic theology as a form of character education already includes aspects of sustainability because an individual has a moral duty to humanity and God (Asif Citation2020). While character (akhlaq) in Islam is seen as an individual’s inward disposition that impacts their outward action, which can be developed through training and habituation (Rahim Citation2013). This refers to the moral and ethical values that a Muslim should strive to sustain in their daily life so they can be considered virtuous. Prophet Muhammed (PBUH) is seen as a role model and medium to learn these values as he embodies the essence of akhlaq through numerous characteristics such as kindness, honesty, respect for others, justice, and fairness. As character (akhlaq) is embedded within Islam, this paper aims to explore the concept of developing a character education programme in Saudi Arabia to help build moral virtues more effectively.

Background

An interest in character education has recently re-emerged at various levels of the school system in different countries as psychologists, philosophers and educationists try to discover how to best develop students’ characters to help them develop holistically (Walker, Roberts, and Kristjánsson Citation2015). Similarly, in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), several initiatives have been conducted based on character/citizenship education over the past decade such as The Global Citizen Forum in the UAE and Saudi national campaign How to be a role model? (Kef nkoon qudwa), which encourages all kinds of leaders: parents, teachers, imams (heads of mosques), and government and private officials to act as role models for their society (Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia Citation2019). Moreover, The United Arab Emirates developed a national moral education programme for all schools in the country. The programme is taught as a separate subject, and the curriculum includes four main pillars: character and morality, individual and community, civic studies and cultural studies, which are intended to foster morals on an individual and societal level (Moral Education Citationn.d.). Although the UAE is also an Islamic state, it follows the religion more moderately than Saudi Arabia both socially and politically. It has a more diverse religious population, requiring a more cosmopolitan moral education programme separate from an Islamic one (Pring Citation2019).

Saudi Arabia has changed drastically throughout the years, for instance, changes in women’s rights; religious reforms allowing for a more moderate Islam; and educational reforms with funding, curricula and technology (Allmnakrah and Evers Citation2020). Still, since Islam is the state religion and Islamic customs and values are at the heart of the country when it was established, religious scholars use the Qur’an and Hadith (listing traditional customs the Prophet promulgated and followed) to establish the law of the country (Alrashidi and Phan Citation2015). Priorities and procedures differ from one school to the next, but the central and prevailing theme within the Saudi curriculum is Islam, whether it is its own subject, the history of Islamic civilisation, the Prophet and his companions, or within Arabic literature based on Islamic teachings (Jamjoom Citation2010; Simmons and Simmons Citation1994; Prokop Citation2003).

Islamic character education

The philosophy behind Islamic education within the Qur’an can be divided into components: ‘tarbyah’ which involves helping children to grow and develop, and ‘ta’lim’ which provides knowledge and learning (Hussain Citation2004). Halstead defines good adults within Islam as being wise and just in addition to balancing physical, emotional and spiritual growth on an individual and societal level (Halstead Citation2007). This is all based on a relationship or attachment to the Divine (Miner et al. Citation2014). However, how Islamic education is implemented in practice has attracted criticism due to its lack of critical thinking. Although there was an educational reform in the Arab and Muslim world after 9/11 by removing some anti-western ideologies (Allmnakrah and Evers Citation2020) further changes in the pedagogy are desired by students and teachers to include more student-led teaching and allow for deeper critical thinking skills (Prokop Citation2003; Jamjoom Citation2010; Elyas and Picard Citation2012). It is essential to highlight character education is at the heart of Islam, but is often misunderstood and miscommunicated within the Western world (Lovat Citation2016).

Apart from governmental regulation and the high place given to religious studies, another aspect of the educational system is the focus on rote learning and memorisation, which fails to foster students’ analytical and creative skills (Rugh Citation2002; Prokop Citation2003). In Jamjoom’s study, exploring female Islamic teachers’ thoughts and experiences in Saudi Arabia, some teachers said they preferred using general and flexible teaching methods rather than specific lesson plans that rely on memorisation. Still, their lack of skills forces them to return to the old teaching style. While discussions occur, the flow of information is one-sidedly from teacher to student or through a teacher asking questions to receive the expected answer (Jamjoom Citation2010). This follows a similar course in other Islamic countries such as Pakistan and Malaysia, where moral values are taught through religion, but has limited reflective dialogue and critical thinking at times (Balakrishnan Citation2017; Asif Citation2020). However, Islamic education is meant to be holistic to ensure a balance between spirituality, morality and the mind (Alwadai and Alhaj Citation2023).

The other source of character development is citizenship education, and according to Alharbi (Citation2017), citizenship education is integrated into social studies. The secondary school has its separate subject, but the focus is more on values that develop students’ national identity rather than on how they can be good global citizens. Faour and Muasher (Citation2011) discuss citizenship education further in the Arab Region, using several examples of curricula in countries such as Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia. They argue it is outdated as they need to focus more on diversity and critical thinking, which are in fact compatible with Islam. The educational focus is more on ‘technical aspects’ which fails to develop the human side such as how to ‘think, seek and produce knowledge’ (1) because, again, the assessment focuses on memorisation rather than critical thinking.

Alharbi (Citation2017) mentions the main deficiencies with citizenship education in the country are its content, aims, and teacher training, in addition to the old-fashioned pedagogy since the subject focuses on a traditional lecture class, resulting in learners taking a more passive role. Ironically, however, this deviates from Islamic pedagogy that seeks to cultivate critical thinking and personalised learning with students that integrates Islamic teachings with modern knowledge and technology (Sabani et al. Citation2016). This is not a new concept in Islam, as during the Islamic Golden Age significant scientific and mathematical theories were spread worldwide (Alexakos and Antoine Citation2005).

Although moral values have not been explicitly mentioned in the campaign, the Saudi Vision 2030 (n.d) declares: ‘ … we intend to embed positive moral beliefs in our children’s characters from an early age by reshaping our academic and educational system … ’ (28). With Vision 2030 looking to transform many aspects of the country, now is arguably an ideal time to introduce new positive educational programmes into the school system, such as character education programmes to aid with moral development and thus to care for sustainable causes.

Islam considers character to involve cognitively understanding morality to maintain character through habituation and practice. Further, using role models is not considered a new concept in Saudi Arabia as the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is the ideal moral exemplar to help understand certain virtues and how to emulate them (Izfanna and Hisyam Citation2012; Asif Citation2020), and moral values and lessons are taught through prophet stories mentioned in the Qur’an and Hadith. Many Islamic scholars such as Al-Ghazali mention the importance of moral education in Islam and highlights that teachers must be authentic role models and guides for children (Alavi Citation2007). Thus, in the section below role-modelling theories are discussed to identify a possible framework within the educational field.

Role-modelling theories

Before developing a possible theoretical role-modelling framework in character education, it is important to discuss the different theories and considerations that could arise. Within the realm of moral theories, the use of moral exemplars for moral development has been a subject of interest (Zagzebski Citation2015; Croce Citation2019; Croce Citation2019; Henderson Citation2022). Zagzebski (Citation2015) has sought to construct a moral theory based on the emotion of ‘admiration’ when encountering an exemplar, positing it as a positive emotion that propels individuals toward emulation. Furthermore, neo-Aristotelian concepts emphasise the importance of incorporating moral exemplars in education, providing learners with an opportunity to reflect on their shortcomings and inspiring progress through the emulation process (Kristjánsson Citation2017). From an empirical standpoint, studies by Algoe and Haidt (Citation2009) and Immordino-Yang and Sylvan (Citation2010) have identified physical and emotional changes in the body when witnessing moral excellence, motivating individuals to adopt an exemplar's moral values.

However, some issues could arise with role-modelling and should be considered when used within education. Firstly the role model could be seen as too superior, and the virtues do not appear feasible for the learner, thus creating a sense of moral inertia (Monin Citation2007; Han et al. Citation2017). Secondly, the feeling of admiration or elevation could develop into hero-worship, causing one to blindly idolise an exemplar without using critical thinking skills (Kristjánsson Citation2017). This can lead to indoctrination as learners fail to use their moral reasoning skills, preventing them from effectively implementing the virtues in their own lives (Osman Citation2019). Therefore to reduce hero-worship, moral inertia, indoctrination, or negative feelings such as envy (Schindler Citation2014; Sarapin et al. Citation2015) it is encouraged within educational practices to include ordinary and relatable exemplars with attainable virtues (Croce and Vaccarezza Citation2017; Han et al. Citation2017; Vos Citation2018; Osman Citation2019). In their study, Han and Dawson (Citation2023) observed that encountering exemplarity through relatable models generates an enhanced sense of elevation and pleasantness, particularly when the exemplified virtues are more achievable. Addressing how moral role models are presented to children and adolescents may mitigate the impact of the issues discussed. The emphasis should not solely be on imitating these models but rather using them as a medium for self-discovery, recognising the ‘significant difference between becoming like the exemplar and becoming what the exemplar exemplifies’ (Vos Citation2018, 22). An effective approach not only involves employing relatable and attainable models, as discussed earlier, but also acknowledging the exemplar's imperfections to reduce any perceived superiority, as this prevents the exemplars from being idolised as flawless individuals on a pedestal (Croce and Vaccarezza Citation2017; Osman Citation2019; Croce Citation2019; Kotsonis and Dunne Citation2023). Furthermore, featuring ‘ordinary’ exemplars emphasises the intricacies of their personalities, offering a more authentic and realistic portrayal of morality.

Role-modelling framework in character education

Although Islam plays an immense role in the country’s education and already uses role-modelling to teach specific values through Islamic moral exemplars the notion here is to expand that and develop a character education programme to include deeper reflection and critical thinking. Leading to the question: how could an effective role-modelling character education programme be developed in Saudi Arabia?

To provide somewhat of a holistic perspective on role-modelling within character education based on the theories discussed and the issues that could arise, one can look at Aristotle’s theory as he encourages the use of role-modelling through the mixed-valence emotion ‘emulation’ to motivate one to act morally. Kristjánsson (Citation2017) develops this further and posits that merely desiring improvement is insufficient for moral growth; it requires three additional steps. Beyond distress, one must cultivate ambition, leading to self-understanding and reasoned self-reflection, which then prompts actions aimed at acquiring the admired qualities in a role model. To effectively employ Aristotelian role modelling, emphasis should be on the qualities exhibited rather than the models themselves. Role models serve as tools for children to comprehend virtuous traits, necessitating a cognitive element for understanding, an affective element to trigger emotions, and a conative element to motivate developmental alignment with the model. Building on this, Henderson (Citation2022) argues that, in accordance with Aristotle, emulation is a virtue in itself because it involves cognitive reasoning, moral emotions, and moral action in the imitation of virtue.

Furthermore, based on a neo-Aristotelian notion, the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (Citation2016) created a framework to guide schools on how to support their students’ character development. They recommend an initial ‘caught’ and ‘taught’ approach, where ‘caught’ precedes ‘taught’ after a period of moral habituation and moral understanding. This approach underscores the significance of fostering a school community that actively promotes character development and includes explicit teaching opportunities both within and beyond the classroom. On the other hand, the ‘sought’ aspect includes ongoing opportunities facilitated by the school to enable students to develop their character in a critical and reflective manner.

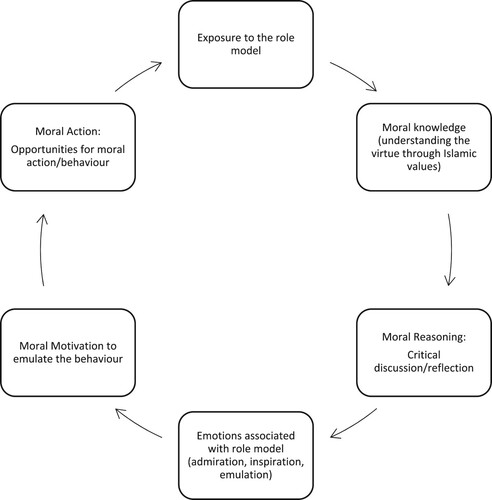

Using this framework and Aristotle’s notion on emulation, , demonstrates a possible role-modelling theoretical framework with elements of caught, taught and sought. Students are first exposed to a relatable moral model to help understand the virtues they exemplify followed by a critical reflection to allow for moral reasoning as well as reducing moral inertia and hero-worship. The aim is to evoke emotions through moral understanding and reasoning, ideally motivating individuals to emulate the virtues demonstrated by the exemplar. Educators and schools should then offer opportunities for students to put these virtues into practice.

Through the interviews, this study will explore whether such a role-modelling character education would be feasible within an Islamic context to develop sustainable development values.

Methodology

Research design and context

The following explorative study is the second stage of a dissertation project, and the data collection and analysis phase of the study was twofold: firstly, it used a qualitative approach to explore perspectives on whether character education and role models within it, can affect pupils’ moral development based on the cultural context. Secondly, mindful of the Saudi context, it proposed exploring how such an educational programme could be developed to increase efficacy. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Birmingham (ERN_18-1865).

Sampling

This stage of the research required various sampling techniques, which started with one inclusion criterion: participants had to be involved in the educational system in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. To yield a comprehensive perspective, purposive sampling sought individuals in specific roles including three student groups, five teachers, six parents, and six consultants/curriculum developers. The recruitment strategy evolved from communicating with school organisations to online advertising, followed by incorporating snowball sampling through word of mouth (Robinson Citation2014). displays the participants’ code names and details.

Table 1. Participant information.

Data collection and analysis

The data collection was qualitative because it sought to explore the personal perspectives of various participants in the educational system within the region. The aim was for the researcher to act as an interpreter to create meaning based on preconceived themes using semi-structured interviews and focus groups. It was deemed that in-depth interviews would help gain various perspectives on character education and role modelling in the country, in addition to how it might be developed in the future, based on participants’ current experiences, values, and interests (Mears Citation2012).

The focus groups were held in person, while interviews were a mix of face-to-face and online sessions, depending on participants’ preferences. The locations included homes, offices and schools, again based on participants’ and/or their guardians’ preferences. The researcher collected and audio recorded all data during these sessions. Interviews and focus groups were conducted in either Arabic, English, or a combination, depending on the participant's comfort or fluency in the respective language.

Recordings were transcribed verbatim by the researcher. van Nes et al. (Citation2010) suggest the translation process should be delayed as much as possible because language is the medium in which information is interpreted in qualitative research and language differences could ‘result in a loss of meaning and thus loss of the validity’ (314). Therefore, quotes were translated solely for the purpose of presenting the researcher's findings by the researcher and a translating software. However, the analysis itself was carried out in the original language to reduce the potential loss of meaning that could occur in translation during the analysis stage.

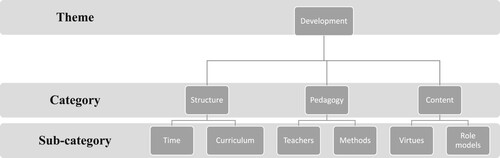

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted, allowing for a deductive and inductive approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) as there were pre-defined themes from the previous stage of this research and the conceptual framework, while new themes emerged during the analysis process. Following Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004) content analysis coding system allowed for an ongoing process of recapitulation that started during data collection leading to the themes shown in .

Results

The categories, sub-categories and codes that emerged from the first theme are conveyed in . The findings are presented through a funnel vision as it looks at the overall structure of how the programme is expected within a school and narrows it down to the actual content. The quotes or part of the quotes which are in brackets have been translated from Arabic to English.

Structure

As the first category, structure, focuses on the programme from a wider perspective, many participants discussed the idea of a character education curriculum more than just a role modelling one. The two sub-categories found under structure were time and curriculum. This involved descriptions or opinions on when to conduct such a programme and for how long, as well as where or how it should be placed in the existing curriculum.

Curriculum

There were different perspectives on how such a programme should be set up in the curriculum, whether it should be taught as a separate subject or just expected to be ‘caught’ (through osmosis) within the school and be embedded in all academic subjects. Although the focus groups did not discuss the curriculum to the same extent, the majority of the adult participants agreed the programme should be embedded into the curriculum, and therefore taught within academic subjects so that it becomes a whole school curriculum.

Out of the three parents who discussed it, all three believed it should be a whole-school approach, so it is consistently part of their children’s lives. At the same time, most teachers and consultants agreed with this for reasons such as children rejecting something dictated to them and that it is a topic that comes naturally but cannot be taught directly. One raised an interesting idea of having it taught through all subjects while also having one main teacher in the school who would coordinate efforts:

It has to be, um, kind of vertical integration into your curriculum in several areas. Um, you can have it in several disciplines as well. It … I don’t think it should be like a concrete block in your curriculum, I think it should be weaved, (this is it), this is the word I’ve been looking for, it should be weaved into your curriculum. (P6)

So, they must have a certain number of Islamic studies instruction, they’ve got to have the Arabic instruction … there is also some kind of conditioning in terms of their culture, and the development of their culture. So, you bring in something else called character development, um, it could look to them, like another dictate. (T3)

If we put it under the context of, ‘we’re talking about morality here’ rather than put it under the context of ‘we’re talking about (religion) or religion because children tend to, just, because its religion, you follow it, you don’t discuss it, you don’t have a conversation about it, we just, we know what the Qur’an said, and we do it. (C4)

Time

Time includes lesson time, lesson frequency, and programme duration. Not all the participants discussed this, as some believed it should not be timetabled on its own, but for those who did, it was suggested each lesson should be as long as the schools’ normal lesson time, between 45 min to an hour. Six participants and two focus groups believed it should be taught throughout the academic year for reasons such as the importance and efficacy of repetition and continuity. In contrast, others thought it was a significant matter that should never stop. Lesson frequency varied from once or twice a week to once or twice a month.

Pedagogy

This category involved the ‘how’ and the ‘who’ in that it examines how participants thought a role modelling character education programme should be taught in the region and who should teach it; thus, the two sub-categories are labelled methods and teachers.

Methods

Within this sub-category all the participants who discussed this matter rejected the idea of a theory-focus and/or encouraged the idea of practicality, either by creating spaces for students to embody these values, learning through movement/corporeal expression, choosing the way they learn or taking charge of it themselves:

Or it could be active learning, where you can go actually ask the student to go and model this kind of value or character in different situations and how, and they reflect on it for example. (C2)

It puts the student more in charge then they are governing what direction they choose to develop in, it doesn't have to be part of a herd mentality, which is what I think we are trying to get them away from. (T3)

Teachers

This sub-category includes anything related to who the teachers should be or what characteristics they should encompass. Three of the participants, two teachers and one parent, mentioned the importance of the teacher being the role model and embodying the virtues taught to their students because students can detect dishonesty and hypocrisy easily and are unlikely to be as inspired by or dedicated to improving their virtues if they fail to see in their teachers who are preaching these values not implementing them as well.

Some participants, including parents, teachers, and curriculum developers/consultants, believed the teacher’s enthusiasm for the subject and the child is what’s important. Therefore, the programme would not be as influential if the teacher were not motivated. Although some participants found a passion for being essential, others believed some sort of training or acquisition of a certain skill was required to teach a character education programme effectively, as many mentioned a lack of teacher training as an issue in the region. Two focus groups mentioned wanting various subject teachers or someone close to them as the main character educator, mainly due to their relationship, and/or how influential they found them. Two teachers supported the children's point in their needing for a relationship between the teacher and students to effectively impart virtues.

Meanwhile, an additional teacher mentioned the relationship between an expatriate teacher and a Saudi one with a student. With expatriate teachers, the students can be more open without judgement and gain a perspective on how people from abroad judge them. This shows there can be different relationship dynamics between teachers and students based on nationality or culture, which should be considered when creating a character development programme:

I’ve observed, there are some conversations that I can have with students that they may not have with other teachers. You’re from the outside, but you are Muslim, ‘so can we tell you this’ ‘what can we tell you about this?’ and ‘do you think it's fair that people look at us and they see x, y, z but really that’s not us?’ (T3)

Content

The content category explores what should be included in the programme. The three sub-categories are the virtues, involving which virtues the participants believed should be taught, and the activities to help them teach those virtues. The type of role models the virtues should be taught through.

Virtues

Several virtues were mentioned, with honesty being the most frequent, with six mentions, followed by responsibility, respect, empathy, and kindness. Other virtues mentioned once or twice were patience, self-love, and authenticity. The virtues chosen were based on the lack of them being foregrounded currently in the region or internationally, such as self-love or the significance on a societal and global level. One parent considered the current education regime to emphasise the importance of capitalism and prepare students for that system while disregarding citizenship values connecting them to their community:

So, if you wanted to teach students, you want him to also be a global citizen, so you can’t only focus on values concerning your society, you have to teach him character and values that are concerning the global society. (C2)

Activities

Students and the various adult participants discussed the activities that should be included in the programme to teach learners virtues through role models. Two focus groups suggested sports, and two focus groups mentioned competitions. Other activities the students raised were field trips, real role models coming into the school, and writing and discussions. The most mentioned activities by adult participants were stories, followed by real role models, projects and role-playing. Other activity examples included discussions, drama, and journaling. Most of the activities mentioned require plenty of student engagement and involvement.

Role models

To explore what kind of role models should be used in a character education programme, the student focus groups were asked who their role models were and what type of role models they would prefer in a school setting. Participants in all three focus groups mentioned a family member, with parents being the most popular choice, and their reasons were mostly about their role models’ character or how they teach them about life. Some adult participants discussed role models being mentors or proximal (i.e. family members or friends). It was seen that, with mentors, learners could gain a deeper understanding when they know the context in which the role model exists; furthermore, that can only happen effectively with those they see around them. One focus group mentioned the educational implications of this by suggesting parents could physically come into the classroom and act as mentors. However, this could include finding activities that included parents or thinking about how their parents had taught them particular moral virtues:

My moral role models are my elder cousins and brother. They show me all difficulties I can go through when I grow up, they give me examples about how I can live life, also they give me advice about what to do and what not to do. My role models will also be my parents because they teach me what to do and how to take care of yourself. (S1)

You usually know the people around you, like you know what their character is, on TV you don’t really know, if they’re really good or if that's just like their outer look or what they’re like inside. (S1)

Two parents and one educational consultant mentioned historical role models but should be presented alongside present-day ones to avoid the pitfalls of using historical models. Historical role models and Islamic civilisation are an integral part of Islam. Therefore, participants felt they were necessary to provide a base, but it should not be the whole focus:

Historical is important because it gives you a good foundation, but history won’t tell you what they’ve done because it’s just a story in the end. So, you need to tie history with someone who is living, the model. (P3)

I think it should definitely be, global figures, I mean not tie it to religious or political views … Um, and it gives the child a wider perspective of morality. I mean just to think that the people I know from my background are good people and they are my role models, is ok, but to give them a bigger picture, is a much bigger lesson. (C4)

And if those role models epitomise aspects of the Prophet Muhammed (PBUH) that’s good, however, if they also epitomise and can show how to navigate modernity, the society, fast changing world that we live in now, that helps. (C6)

Discussion

Before developing and implementing a role modelling character education programme, the following study examines different stakeholders’ perspectives on how it should be executed.

Participants considered there to be a lack of focus on character education, believing it is rarely taught or not taught enough, and this could be because citizenship education in primary school is delivered through the humanities subjects (Alharbi Citation2017). Many agreed, that morals are taught through Islamic studies, yet similar to existing evidence (Jamjoom Citation2010; Prokop Citation2003) change is desired in this field because how the moral component of Islamic studies is taught is outdated, as it mainly uses rote learning and memorisation, which students do not positively receive.

The most often mentioned pitfall of character education and role modelling is indoctrination, as there is a risk of uncritically copying an exemplar (Croce Citation2019; Kristjánsson Citation2017) therefore, it is important to focus on the virtues more than the role models as well as encouraging critical thinking and moral reasoning (Sanderse Citation2013). A few participants agreed with this concept, as one teacher was worried a role modelling programme could be yet another dictated element, which they already receive from other mandatory humanity subjects; and a curriculum developer recommended the programme being separate to religious studies so there was room for critical discussion. Although critical thinking is a long-standing tradition in Islamic education, the way it is currently taught has deviated from that. Even citizenship education in Saudi Arabia, as Alharbi (Citation2017) mentions, fails to teach students global values, and focuses on a national identity to tie them with the state. This comes with further danger of indoctrinating young individuals, thus the idea of this programme is to emphasise the importance on critical discussion and reflection through a variety of models to ensure they are learning global values to help develop global moral citizens.

Therefore, a possible way of conducting such a programme would be to emphasise the importance of emulating the virtues presented by the exemplars and modifying them in accordance with one’s own life pursuits and identity. Croce (Citation2019) and Han (Citation2015) recommend using student-led activities to effectively use role models in classrooms and allow space for discussions. Projects could include acting on the virtues taught such as: planting a tree, volunteering, peer-mentoring, creating and managing a charity event. This also allows the students to see how virtues can be attained on a practical and smaller scale rather than seeming inaccessible through the exemplars and causing moral inertia, defined as the demotivation to morally develop because the virtues and/or exemplars seem too superior (Han et al. Citation2017).

Regarding the significance of role modelling, participants referred to similar underlying concepts as they perceived it as an effective method for teaching virtues. Role modelling was seen as effective because it provides a practical technique with real examples, a method described as more useful than theoretical teaching. Moreover, the findings supported theories suggesting certain emotions are elicited when exposed to moral exemplars (Algoe and Haidt Citation2009; Schindler Citation2014; Thrash et al. Citation2014; Zagzebski Citation2015; Kristjánsson Citation2016) as most of the students explained feeling inspired and motivated to do and be better when exposed to moral role models. However, some adults acknowledged the pitfalls of role modelling, which mainly involved hero-worship and perceiving certain exemplars as perfect without noticing their weaknesses, as Croce (Citation2019) and Kristjánsson (Citation2017) discussed, or possibly feeling devastated when certain flaws are revealed. The advice given by participants involves revealing the role models’ full story and including their weaknesses and struggles from the beginning. However, none of the participants mentioned the role models being too superior to emulate because of unattainable virtues (i.e. moral inertia). However, this notion links to Islam because showing exemplars’ struggles and imperfection is demonstrated through many of the prophets, as they are shown to have made mistakes themselves and to ask God for forgiveness, such as the Prophets Yunus, Adam and Moses (Qur’an 21:87; 7:23; 7:151).

Using religious models who are held in high esteem was mentioned, especially Prophet Muhammed (PBUH), but most of the participants who did mention this point said it was also necessary to include other role models with more ‘modern’ values. This is not surprising because, in Islam, following the Prophet’s moral ideals is the foundation of the religion, but it is important to elucidate that participants did not believe this by itself would be effective. This finding concurs with Vos’s (Citation2018) point that extraordinary exemplars can give someone the chance to define their ‘ideal self’ (25), which prophets can provide as the highest moral image, but ordinary exemplars are effective in showing the regular everyday struggles to which learners can relate.

The findings show that all participants were open to teaching virtues through role models; therefore, even if it was not explicitly stated, taking an Aristotelian approach would potentially be positively received. Following the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (Citation2016) concept on character education being ‘taught’, ‘sought’ and ‘caught’ the programme could be embedded within curriculum and can in fact be cross-curricula allowing a variety of role models from ordinary to extraordinary and local to global. The values the exemplars possess should only be a medium for a learner to deepen their understanding, and for effective change. Therefore, after exposure to the role model and a critical discussion about the virtues they entail, self-reflection is required to see how they can embed these virtues in their own lives. Islam would be the foundation, but there should be opportunities through different classes and extracurricular activities to allow for more student-led activities and critical reflection. The emotions associated with learning about the exemplars could provide a better understanding of moral values and thus leading to the motivation to emulate them.

Conclusion

The findings and literature convey a change is needed in the region regarding character education to allow young learners to develop into moral global citizens and create a sustainable future. Role-modelling is already a teaching method in the region, even if it is not labelled as such, because moral teachings are performed throughout Islamic history using the Prophet and his companions as models. As the findings show, the next step would be modifying how it is currently executed with a more effective method using the right pedagogy and content. After synthesising the findings and wider literature, the conceptual framework introduced () could be implemented to ensure a balanced approach to character education through role models. It may not necessarily occur in the exact order, but a role model could be used to introduce and teach students the meaning of particular virtues such as honesty or integrity. This can be followed by opportunities to critically discuss and self-reflect on the virtues learnt, so as to reduce indoctrination and help them discover their own moral identity. When moral motivation is guided by the teacher through the emotions associated with learning about an exemplar, it should be followed by a more student-centered and dynamic approach. Activities could involve students conducting hands-on tasks such as finding their own role models and interviewing them or researching about them, volunteering or creating and managing initiatives with moral objectives. This allows for an opportunity for practitioners and researchers to develop a character education programme that creates space for moral reflection to help hone the appropriate skills and develop the right values. This study, however, does not come without its limitations as it was small-scale and conducted individually for a PhD project, therefore more in-depth research is recommended to see how character education can be implemented effectively to ameliorate the gap in the field. Focusing on children’s moral development can provide a strong foundation for them to become global citizens and care for a sustainable future.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my supervisors at the University of Birmingham for their support throughout the research and writing phases of this doctoral project. I am also indebted to Middlesex University Dubai for facilitating the publication process. Additionally, I would like to express my appreciation to the reviewers for their invaluable feedback, which significantly enhanced the quality of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alavi, Hamid Reza. 2007. “Al-Ghazāli on Moral Education.” Journal of Moral Education 36 (3): 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701552810.

- Alexakos, Konstantinos, and Wladina Antoine. 2005. “The Golden Age of Islam and Science Teaching.” Science Teacher 72 (3): 36–39.

- Algoe, Sara B., and Jonathan Haidt. 2009. “Witnessing Excellence in Action: The “Other-Praising” Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 4 (2): 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802650519.

- Alharbi, Badr Abdullah. 2017. “Citizenship Education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: History and Current Instructional Approaches.” International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies 5 (4): 78–85. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.4p.78.

- Allmnakrah, Alhasan, and Colin Evers. 2020. “The Need for a Fundamental Shift in the Saudi Education System: Implementing the Saudi Arabian Economic Vision 2030.” Research in Education 106 (1): 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523719851534.

- Alrashidi, Oqab, and Huy Phan. 2015. “Education Context and English Teaching and Learning in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Overview.” English Language Teaching 8 (5): 33–44.

- Alwadai, Mesfer, and Ali Alhaj. 2023. “‘Investigating Male and Female Teachers’ Perceptions of Character Education in High School Islamic Studies Curricula in Saudi Arabia’.” Technium Social Sciences Journal 40 (February): 117–131. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v40i1.8376.

- Asif, Tahseen. This link will open in a new window Link to external site, Ouyang Guangming, this link will open in a new window Link to external site, Muhammad Asif Haider, Jordi Colomer, this link will open in a new window Link to external site, Sumaira Kayani, and Noor ul Amin. 2020. “Moral Education for Sustainable Development: Comparison of University Teachers’ Perceptions in China and Pakistan.” Sustainability 12 (7): 3014. . https://doi.org/10.3390/su12073014.

- Balakrishnan, Vishalache. 2017. “Making Moral Education Work in a Multicultural Society with Islamic Hegemony.” Journal of Moral Education 46 (1): 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1268111.

- Berkowitz, Marvin W. 2002. ‘The Science of Character Education’.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Croce, Michel. 2019. “Exemplarism in Moral Education: Problems with Applicability and Indoctrination.” Journal of Moral Education 48 (3): 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2019.1579086.

- Croce, Michel, and Maria Silvia Vaccarezza. 2017. “Educating Through Exemplars: Alternative Paths to Virtue.” Theory and Research in Education 15 (1): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878517695903.

- Elyas, Tariq, and Michelle Yvette Picard. 2012. ‘Teaching and Moral Tradition in Saudi Arabia: A Paradigm of Struggle or Pathway Towards Globalization?’ Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, Cyprus International Conference on Educational Research (CY-ICER-2012) North Cyprus, US08-10 February, 2012, 47 (January): 1083–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.782

- Faour, Muhammad, and Marwan Muasher. 2011. ‘Education for Citizenship in the Arab World: Key to the Future’, October. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/430761/education-for-citizenship-in-the-arab-world/1401849/.

- Graneheim, U. H., and B. Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24 (2): 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Halstead, Mark, J. 2007. “Islamic Values: A Distinctive Framework for Moral Education?” Journal of Moral Education 36 (3): 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701643056.

- Han, Hyemin. 2015. “Virtue Ethics, Positive Psychology, and a New Model of Science and Engineering Ethics Education: Science & Engineering Ethics”. Science & Engineering Ethics 21 (2): 441–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-014-9539-7.

- Han, Hyemin, and Kelsie J. Dawson. 2023. “Relatable and Attainable Moral Exemplars as Sources for Moral Elevation and Pleasantness.” Journal of Moral Education 0 (0): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2023.2173158.

- Han, Hyemin, Jeongmin Kim, Changwoo Jeong, and Geoffrey L. Cohen. 2017. “Attainable and Relevant Moral Exemplars are More Effective Than Extraordinary Exemplars in Promoting Voluntary Service Engagement.” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (March): 283–283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00283.

- Henderson, Emerald. 2022. “The Educational Salience of Emulation as a Moral Virtue.” Journal of Moral Education 0 (0): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2022.2130882.

- Hussain, Amjad. 2004. “Islamic Education: Why Is There a Need for It?” Journal of Beliefs & Values 25 (3): 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361767042000306130.

- Immordino-Yang, Mary Helen, and Lesley Sylvan. 2010. “Admiration for Virtue: Neuroscientific Perspectives on a Motivating Emotion”. Contemporary Educational Psychology, Special Issue on 'Brain Research, Learning, and Motivation' 35 (2): 110–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.003.

- Izfanna, Duna, and Nik Ahmad Hisyam. 2012. “A Comprehensive Approach in Developing Akhlaq: A Case Study on the Implementation of Character Education at Pondok Pesantren Darunnajah.” Multicultural Education & Technology Journal 6 (2): 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/17504971211236254.

- Jamjoom, Mounira I. 2010. “Female Islamic Studies Teachers in Saudi Arabia: A Phenomenological Study.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.019.

- The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. 2016. A Framework for Character Education in Schools. Available at: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/1606/character-education/publications (Accessed: 20 June 2023).

- Kotsonis, Alkis, and Gerry Dunne. 2023. “The Harms of Unattainable Pedagogical Exemplars on Social Media.” Journal of Moral Education 0 (0): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2023.2225763.

- Kristjánsson, Kristján. 2016. Aristotle, Emotions, and Education. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315567914

- Kristjánsson, Kristján. 2017. “Emotions Targeting Moral Exemplarity: Making Sense of the Logical Geography of Admiration, Emulation and Elevation.” Theory and Research in Education 15 (1): 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878517695679.

- Lovat, Terence. 2016. “Islamic Morality: Teaching to Balance the Record.” Journal of Moral Education 45 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2015.1136601.

- Mears, Carolyn. 2012. “In-Depth Interviews.” In Research Methods and Methodologies in Education, edited by James Arthur, Michael Waring, Robert Coe, and Larry Hedges, 170–176. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Miner, Maureen, Bagher Ghobary, Martin Dowson, and Marie-Therese Proctor. 2014. “Spiritual Attachment in Islam and Christianity: Similarities and Differences.” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17 (1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.749452.

- Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia. 2019. “How to be a Role Model?” https://edu.moe.gov.sa/jeddah/JeduAdmin/Pages/كيف-نكون-قدوة.aspx (Accessed: 12 October 2020).

- Monin, Benoît. 2007. “Holier Than Me? Threatening Social Comparison in the Moral Domain.” Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 20 (1): 53–68.

- Moral Education – Moral Education. n.d. Accessed 31 January 2023. https://moraleducation.ae/.

- Nes, Fenna van, Tineke Abma, Hans Jonsson, and Dorly Deeg. 2010. “Language Differences in Qualitative Research: Is Meaning Lost in Translation?” European Journal of Ageing 7 (4): 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y.

- Osman, Yousra. 2019. “‘The Significance in Using Role Models to Influence Primary School Children’s Moral Development: Pilot Study’.” Journal of Moral Education 48 (3): 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2018.1556154.

- Pring, Richard. 2019. “Development of Moral Education in the UAE: Lessons to Be Learned.” Oxford Review of Education 45 (3): 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1502169.

- Prokop, M. 2003. “Saudi Arabia: The Politics of Education.” International Affairs 79 (1): 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00296.

- Rahim, Adibah Binti Abdul. 2013. “Understanding Islamic Ethics and Its Significance on the Character Building.” International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 508–513. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJSSH.2013.V3.293.

- Robinson, Oliver C. 2014. “Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 11 (1): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543.

- Rugh, William A. 2002. “Education in Saudi Arabia: Choices and Constraints.” Middle East Policy 9 (2): 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4967.00056.

- Sabani, Noraisikin, Glenn Hardaker, Aishah Sabki, and Sallimah Salleh. 2016. “Understandings of Islamic Pedagogy for Personalised Learning.” The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology 33 (2): 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-01-2016-0003.

- Sanderse, Wouter. 2013. “The Meaning of Role Modelling in Moral and Character Education: Journal of Moral Education”. Journal of Moral Education 42 (1): 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2012.690727.

- Sarapin, Susan H., Katheryn Christy, Louise Lareau, Melinda Krakow, and Jakob D. Jensen. 2015. “Identifying Admired Models to Increase Emulation: Development of a Multidimensional Admiration Scale”. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development 48 (2): 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175614544690.

- Schindler, Ines. 2014. “Relations of Admiration and Adoration with Other Emotions and Well-Being.” Psychology of Well-Being 4 (1): 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-014-0014-7.

- Simmons, Cyril, and Christine Simmons. 1994. “Personal and Moral Adolescent Values in England and Saudi Arabia.” Journal of Moral Education 23 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724940230101.

- Thrash, Todd M., Emil G. Moldovan, Victoria C. Oleynick, and Laura A. Maruskin. 2014. “The Psychology of Inspiration.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 8 (9): 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12127.

- UNESCO. 2018. What is Global Citizenship Education? Accessed 15 December 2022. https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced/definition.

- Vos, Pieter H. 2018. “Learning from Exemplars: Emulation, Character Formation and the Complexities of Ordinary Life.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 39 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2017.1393295.

- Walker, David I., Michael P. Roberts, and Kristján Kristjánsson. 2015. “Towards a New Era of Character Education in Theory and in Practice.” Educational Review 67 (1): 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.827631.

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2015. “‘Admiration and the Admirable." Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volumes 89: 205–221.