ABSTRACT

This study aims to advance the understanding of for-profit Chinese education during the tenure of Chairman Xi Jinping. Notably, Xi has recently targeted the privately operated, for-profit before-and-after school supplementary tutoring industry, commonly referred to as “Shadow Education”. In 2021, the introduction of the Double Reduction policy abruptly prohibited most SE businesses. Our research seeks to elucidate the impacts of this sudden policy shift on Chinese parents’ perceptions and decision-making regarding their children’s education and supplementary learning opportunities. Conducted in 2022 across mainland China, our study engaged 195 parents through an online survey followed by two focus group interviews. The investigation was driven by the primary research question: How did Chinese parents, whose children previously participated in SE, respond to the 2021 Double Reduction policy? The analysis is framed with Foucault’s theory of biopower, which envisions power as permeating all spheres of human life. This theoretical framework is particularly relevant as Chinese education under Xi Jinping’s government is increasingly exemplifies the pervasive influence of biopolitics across all facets of society and learning. We aim to address a critical gap in the study of Chinese education, focusing on the intricate interplay of policy analysis amidst broader social and economic forces.

Introduction

In this paper, we, four authors from different universities in China and Australia, aim to contribute to a growing body of research on the recent disruptions in the for-profit sector of Chinese education during the rule of Chairman Xi Jinping. Xi governs with extensive control over many aspects of Chinese society and has recently expressed strong disapproval of the privately operated, for-profit, before-and-after school supplementary tutoring industry, commonly known as “Shadow Education” (Bray Citation2014; Bray Citation2022; Li Citation2019) or SE. For decades, SE has been favoured by middle-class Chinese families, based on the widely held belief that additional tutoring helps students succeed in the highly competitive, exam-driven Chinese education system and society.

The socio-political context of this paper revolves around the unexpected decree by the Chinese government on July 24th 2021, introducing the Double Reduction policy (DRP). This policy abruptly outlawed most businesses in the SE sector, which was valued at approximately $140 billion annually. The Communist government justified its decision by stating that the industry had been “severely hijacked by capital” (Chau, Cheng, and Fang Citation2021). The DRP also intended to reduce the homework load of students and eliminate perceived unfair advantages by restricting extra tutoring that wealthier families could afford. This policy change was driven by the government’s intention to “rein in the competitive excesses of market capitalism” (Liu Citation2022) in China’s education sector.

Our study sought to better understand the impacts of the sudden initiation of the DRP on Chinese parents’ perceptions and decision-making regarding their children’s schooling and supplementary learning options. We aimed to explore how this significant policy shift influenced parents’ attitudes and choices in the wake of the drastic changes imposed on the SE industry.

Our research was conducted in 2022 and involved 195 parents from across mainland China, with the majority coming from within the Shandong Province and specifically Jinan City. They participated in an online survey and followed by two focus-groups. We were guided by the overarching research question: How did Chinese parents, whose children participated in before-and-after school tutoring from the Shadow Education industry, perceive and respond to the 2021 DRP?

We framed the analysis of our research within Foucault’s (Citation2003) theory of biopower, which conceptualises power permeating into all spheres of human life and activities. We argue that this framing is crucial for understanding the comprehensive impact of the DRP on Chinese education and parental decision-making, and we will explore it further in later sections of this paper.

Education reduction policies in context

Education reduction decrees have been policy objectives in China since at least 1955 (Wang Citation2023). Collectively they have been designed to reduce the learning burden on children outside regular school hours. The rationale behind these reductions seems to be that supplementary education before and after school, as well as on weekends, imposes a stressful burden detrimental to individual students, their families and society as a whole.

In comparison, China’s post-Mao communist leaders have taken pride in the significant advancements made in public, government-funded, compulsory K-9 education. This pride culminated in the realisation of Deng Xiaoping’s long-held dream in 2011, when free schooling became universally accessible to students across both rural and urban China, exempting them from school fees (Wang Citation2023). However, the high-stakes nature of the year 9 exams, the Zhongkao, complicates this progress. With a pass rate of only 50%, students who fail it have limited options (Chen Citation2023). They may pursue further vocational, blue-collar training if they have an interest in a trade and their parents can afford to fund their training costs. Otherwise, those who graduate with only a year 9 certificate often face the prospect of entering the unskilled, labour-intensive workforce. These options are typically wealth limiting and are perceived as a shame for the family, who fear the young person will be doomed to fail in society. The incredibly high stakes of the Zhongkao help to explain why parents and students in China have been willing to invest so much time and effort into for-profit exam preparation and why the DPR was such an earth-shattering policy U-turn that many felt needed to be resisted.

A significant development in regulatory action occurred in July 2021 when the Chinese State Council issued a directive: the “Notice on Further Reducing the Work Burden of Students in Compulsory Education and the Burden of Off-campus Training” (Ministry of Education of PRC Citation2021). This landmark policy, widely known as the “Double Reduction” policy, aspired to mitigate the academic pressures on students, improve their physical and mental well-being, and alleviate the financial burdens on families caused by the perceived voracious reach of the SE industry.

However, the intentions and efficacy of this policy have become contentious. The DRP’s goals are to dismantle the entrenched culture of excessive academic load and to reduce dependency on after-school tutoring, yet how these objectives are interpreted, enacted, and substantiated by parents, teachers, and students remains largely unknown.

Literature on Shadow Education

Shadow Education, a term coined to describe supplementary tutoring outside regular schooling, is named due to its mimicking of formal educational content. As school curricula evolve, so does the content of SE, creating a parallel education system. This phenomenon, initially prominent in East Asia, has now become a global phenomenon (Bray Citation2022).

Internationally, research highlighted that SE has transitioned from an emergent stage, characterised by informal tutoring, to a capitalised stage, where major institutional providers have integrated into educational capital markets (Bray Citation2022; Entrich and Lauterbach Citation2021; Kim and Jung Citation2019). Despite warnings from scholars about SE’s drawbacks – such as exacerbating educational inequality (Yung and Bray Citation2017; Entrich and Lauterbach Citation2021); intensifying students’ competition (Zhang and Bray Citation2015; Zwier, Geven, and van de Werfhorst Citation2020); as well as adding financial burden to household expenditure (Javadi and Kazemirad Citation2020; Kim and Jung Citation2019) – families across the globe continue to enroll their children in SE in hopes of securing a competitive edge in education.

For instance, a 2017 survey of 21,000 primary and secondary students across 29 Chinese provinces found that nearly half (48.3%) participated in SE, with an average annual expenditure of 5,616 Yuan per student (Wei Citation2020). Similarly, a global study of SE across 63 societies by Entrich and Lauterbach (Citation2021) revealed that many high socio-economic status (SES) families invest more in SE to maintain their social status and achieve upward mobility, thereby impacting educational equity and reinforcing social stratification in many societies.

In previous research about China’s education reduction policies, a majority of surveyed parents (n = 6744) whose children are enrolled in SE institutions, expressed dissatisfaction with the government’s previous reduction initiatives (Yang and Chen Citation2019). Among these parents, 60.6% deemed the policy “very ineffective”, and an additional 27.4% found it “not effective”, highlighting scepticism regarding reduction policies’ efficacy even before the implementation of the DRP.

In response, the DRP was formulated to address these issues by aiming to improve students’ physical and mental well-being and reduce family spending (Qian, Walker, and Chen Citation2024). However, the implementation of the policy faces significant challenges: resistance from SE providers, parents who believed in the efficacy of supplementary education, as well as students accustomed to the intensive study culture. A central concern regarding students’ participation in SE was extended amount of time and stress levels that were articulated by parents and teachers (Dello-Iacovo Citation2009; Wang Citation2023).

While recent literature covers the impact of SE and the rationale behind regulatory policies, there remains a notable gap in understanding parents’ perceptions of these policy changes. Investigating parents’ views on DRP could provide valuable insights into the acceptance and potential challenges of policy implementation and may reveal the struggles and complexities involved. Our study sheds light on parents’ responses to the potential disconnects between policy objectives and parental expectations, because understanding these perceptions is crucial for evaluating how effective the DRP has been.

Methods

Our study employed a qualitative research design because, as Newby (Citation2014, 104) suggests, qualitative approach embraces a “soft, descriptive and concerned with how and why things happen as they do.” Our goal was to understand the impact SE had on parents’ choice after the implementation of the DRP. So, we wanted to understand the experiences of those parents whose options for their children had been altered since the policy enactment. We also wanted to understand what strategies these parents might have employed to minimise the impact on their children’s education potential.

As our collective effort comprised of researchers from diverse backgrounds spanning China and Australia, reflexivity was integral to critically examining how our own perspectives, biases, and cultural lenses may have influenced the collection of interpretation and analysis of the data. Two of our researchers are academics within the Chinese education system, and as they had children of their own participating in SE, they offered an intrinsic understanding of the phenomenon. Their positionality allowed for an in-depth interpretation of participants’ responses within an appropriate cultural framework. The non-Chinese Australian academic, despite lacking proficiency in Mandarin, actively engaged in collective discussions with Chinese team members and asked questions to ensure a broader representation of the participants’ views. Lastly, the first author, being both an insider and outsider researcher (Dwyer and Buckle Citation2009), brought a unique blend of cultural understanding and methodological rigor to the study. This researcher is positioned to bridge cultural gaps, drawing upon her native linguistic skills and familiarity with Western academic standards. These diverse perspectives enabled the team to navigate the nuances of the data effectively, ensuring that the analysis reflected both the participants’ cultural contexts and the methodological expectations of international research.

Our research also employed a culturally sensitive approach and, like other research into China during and post the Covid pandemic, the use of virtual means, such as recruitment via online social media platforms, was necessary (Cunningham et al. Citation2022; Liu Citation2022). Our Chinese-Australian research team designed the study over a twelve-month period of clarifying study directions, learning new information, and interpreting the policy between Mandarin and English (and vice-versa). As a team, we decided to publish our questionnaire (Appendix 1) on the Chinese WeChat online survey platform to reach potential participants. There were two main considerations behind that decision. Firstly, WeChat online surveys have become ubiquitous and there has been increasing numbers of Chinese researchers using this function to complete their research studies (Yang et al. Citation2016). Secondly, WeChat is inside the Chinese “firewall” where easy access to the questionnaire was made possible (Cunningham et al. Citation2022). We also incorporated two face-to-face focus-groups conducted by our Chinese academics to gather a broader spectrum of evidence and perspectives from parents who had enrolled their child into a wide range of for-profit SE services.

Data collection procedures

The study was structured with a two-phase data collection approach. Initially, an online WeChat questionnaire was distributed among Chinese families with one or more children enrolled in K-12 schools in China. Subsequently, two face-to-face focus groups were conducted, involving ten of the Chinese parents, who completed the WeChat questionnaire.

These interviews delved into their perceptions and experiences regarding the impact of the DRP and their responses to this policy change. The preliminary analysis of the online questionnaire yielded a comprehensive overview of how families and parents responded to the policy change. This initial phase guided the formulation of a set of open-ended questions, which were posed during the face-to-face focus groups. The iterative nature of this data collection process facilitated a deeper exploration of participants’ perspectives.

Participants

Participants were recruited through a process of purposeful WeChat snowball sampling and public invitation through our Chinese researchers’ professional networks in the SE industry. After ethics approval from Shandong Normal University, the two researchers who are based in Jinan, started to invite eligible participates from their professional contacts on WeChat. Invited families were directed to the questionnaire with a hyper link, which could also be shared with other interested members and families who also met the participant criteria.

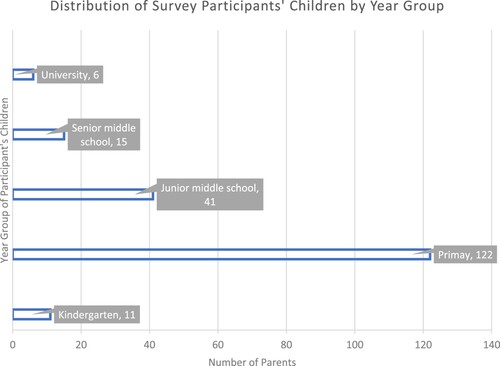

There were two key criteria for participant selection. Participants had to physically reside in mainland China, and they had to have at least one child attending K-12 schooling during the period of data collection. A link to access our online questionnaire was opened between 1st February till the 31st of March 2022. During this period, the questionnaire was viewed and circulated 711 times, and 195 people completed this survey. As shown in , the majority of participants were parents of primary school students (62% of the total), followed by those parents with junior middle school students (21%).

At the end of the online questionnaire, potential participants had an option to fill in their contact information voluntarily so as to be contacted by the research team to join a face-to-face focus group later in that same year. There were ten parents willing to discuss with us their perceptions of the implementation of DRP and their overall experience. Thus, our Chinese research team organised two focus groups: one with parents of primary school students and one with parents of junior middle school students. The demographic features of those participants are summarised in .

Table 1. Demographic features of participants in focus group interviews.

The focus group participants were self-selected from a larger survey pool, meaning they chose to partake in the research based on their interest and availability. This self-selection process may have introduced some bias, as those who opted to participate may have possessed distinct interests or motivations compared to those who did not. Robinson (Citation2014) argues that achieving complete predictability in determining the appropriate sample size for interview-based research may be inherently challenging. To address this potential self-selection bias, we employed several strategies. Firstly, we provided comprehensive information about the study’s purpose and assured confidentiality to encourage a diverse range of participants. Secondly, we compared the demographic characteristics of our focus group participants with the broader survey respondents to identify any significant deviations. We found there were none; still this comparison helped in contextualising our findings and understanding the extent of representativeness.

Initial data analysis

Primary data analysis commenced promptly after the online questionnaire reached the number of 195 respondents. The questionnaire was designed to capture three key dimensions concerning parents’ experiences with the DRP: understanding of the DRP, responses to the DRP, and future planning following the DRP’s implementation. Upon completion of data collection, we downloaded the dataset from the WeChat online survey platform and imported it into SPSS for analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarise and describe the data, which we detail in this paper’s results section. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, we de-identified and re-grouped participants according to the grade levels of their children. This stratification allowed for a more nuanced analysis of the data, providing insights into how parents’ experiences and perceptions of the DRP might vary depending on their children’s educational stages.

Data from focus-groups were transcribed and translated by the Chinese researchers. These transcripts were subsequently cross-checked by all researchers. In doing so, we shared the concerns of Miles and Huberman (Citation1994, 55) that both data analysis and “data collection is inescapably a selective process.” We acknowledge that relying solely on transcriptions may have resulted in a loss of richness in our dataset, as the context-specific insights and some non-verbal cues observed during the focus groups may not have been fully captured.

The transcribed and translated text from the focus groups underwent separate coding by all researchers initially. Each researcher independently identified patterns within the data, applying codes that captured the essence of the participants’ responses. Some examples of those codes included: “parents’ concerns and stress”; “clandestine engagement”; and “exhausted children.” All codes were then cross validated, articulated, and deliberated upon among the research team. The high degree of similarity in our initial coding suggested the reliability of our approach. We believe this collaborative approach ensured that different perspectives were considered that our initial coding process was robust and comprehensive, and well aligned with Newby’s (Citation2014) recommendations for team-based coding practices, which emphasises the importance of consistency and efficacy in qualitative research.

Data synthesis and theorising

In this stage of our research collaboration, we analysed our coding from a critical policy analysis perspective, particularly drawing on the theoretical works of Michel Foucault (Citation2003) and recent studies that have utilised Foucauldian theorising to examine various aspects of Chinese education (Kwok Citation2023; Greenhalgh and Winckler Citation2005). We explored how the Communist Party of China maintains the dominant discourse on education in China, critiquing private tutoring as emblematic of relentless academic competition and the commodification of learning through SE (Bray Citation2009). The DRP policy was introduced to address these entrenched issues, with the rationale that prohibiting SE would enhance individual student well-being and ensure equitable access to education across cohort.

However, as we critically analysed what the parents had told us in the focus groups, it became evident that the government’s rhetoric surrounding the DRP not only reinforced the underlying power structures of government-controlled schooling but may also have perpetuated socio-economic disparities. Our data highlighted the inherent tensions between the policy’s stated goals and its actual outcomes.

Foucault’s work on truth, power and the constitution of the subject (Foucault Citation1997, Citation2006) was instrumental for this part of our analysis, as it enabled us to consider the construction of educational policies and their productive and unproductive effects on middle-class families in China (Kipnis Citation2013; Zhao Citation2019). We examined whether the DRP functioned as a biopolitical strategy aimed at shaping the population’s future actions and choices by both constraining and promoting specific aspects of schooling? This led us to question the implications of Xi’ government further centralising control over after-school opportunities and limiting alternative educational avenues. Specifically, we considered whether the policy reinforces state authority and existing socio-economic hierarchies or perpetuates the very inequalities it seeks to address? In the following sections, we present findings from the online questionnaire and focus groups.

Results from WeChat questionnaire

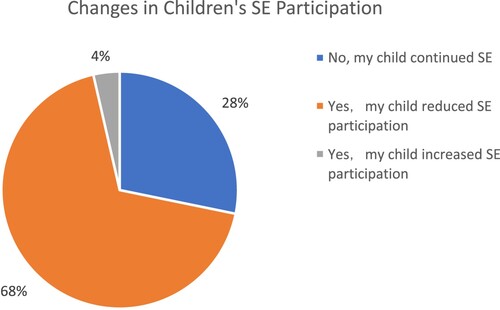

WeChat questionnaire responses indicated since the implementation of the DRP, there has been a significant reduction in children’s participation in SE across all levels of schooling. As shown in , 68% participating parents suggested that their child/children reduced the time spent on SE in subject areas such as numeracy and literacy, while 28% stated their child/children continued SE participation. This data aligns with the parent’s self-reported SE expenditure.

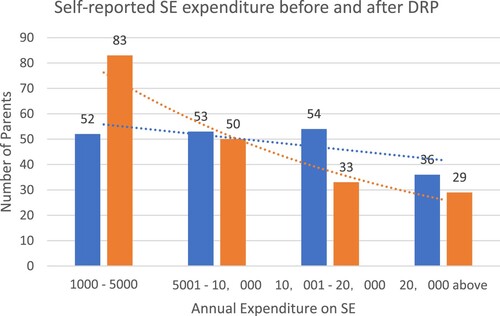

The following suggested that a significant decrease in SE expenditure occurred across three categories after the implementation of the DRP. For example, the number of parents who used to spend between 10,001 and 20,000 Chinese Yuan for their children’s SE participation prior the implementation of DRP, dropped from 54 to 33 after the DRP enactment, while the number increased from 52 to 83 for those parents in the category of SE spending between 1,000 and 5,000 Chinese Yuan.

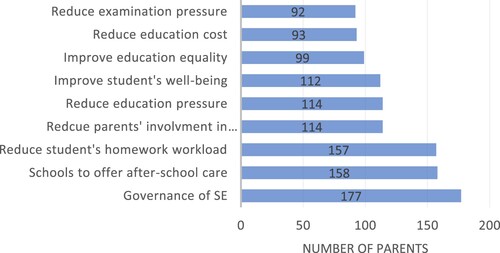

Our questionnaire data illustrates various perceived importance or impact by DRP according to the number of participating parents. The highest number of respondents (177) identified the governance of SE as a key DRP intention. This was followed by the need for schools to offer after-school care (158 respondents) and the reduction of students’ homework workload (157 respondents). These three areas highlight significant concerns about the structure and support of students’ educational experiences outside of regular school hours. Additionally, issues such as reducing parents’ involvement in education and overall education pressure were each highlighted by 114 respondents. This suggested that these are critical areas where parents seek relief and support. The least prioritised issues were reducing education costs (93 respondents) and examination pressure (92 respondents), which, while still significant, were not as pressing as the need for structural and supportive changes. summarises the data:

We also inquired about the parents’ views on the effectiveness of the DRP in reducing their children’s learning stress or improving their well-being. Our result reveals a nearly equal split between the parents who considered the policy effective (33%) and those who did not (34%). Further, 21% of the parents reported that their children’s stress level had increased since the implementation of the policy. These findings indicated that the DRP had mixed and varied impacts on students’ physical and mental well-being.

Our data further revealed the parents’ concerns about two issues that were not directly addressed by the DRP. The first was the quality of teaching and the second was the structure of China’s examination system. This suggests that a significant source of pressure for the parents and the students was related to the high-stakes examinations such as Gaokao (university entrance examination) and Zhongkao (secondary school entrance examination), which determines students’ academic and career prospects.

Results from focus-groups

We conducted two focus-groups to explore how the parents adjusted their children’s learning goals and plans in response to the DRP. The first focus group comprised four mothers collectively responsible for six primary school children, while the second focus group involved six parents with children in junior middle schools. A list of questions we used for focus groups can be found in Appendix 2.

Interestingly, all parents did not intend to lower their expectations regarding their children’s academic achievement or aspirations for admission to prestigious middle school and high schools. Instead, they voiced concerns and criticisms pertaining to the DRP itself. For instance, one mother stated:

I am very worried about my son’s future. He has been enrolled in a mathematics extension program since year 3, as you know, many of his classmates do. We want him to continue to excel in math and have more opportunities to enter the best middle school in the area next year. But now, with the change, he can’t attend the training program anymore and he has to spend less time on additional training as told by the school teacher. I think it is unfair and even harmful for his academic development and education in general.

Parents participating in both focus groups told us that subsequent to the implementation of the DRP, they had found themselves increasingly compelled to clandestinely engage with private tutoring services. This behaviour was likely to be driven by their desires to address their children’s individual academic needs and to uphold their competitiveness. As one example, a mother reported instead of attending regular SE classes, she utilised an online tutoring service, that provides live and recorded lessons for various subjects. Other parents mentioned that teachers and tutors who previously worked at large for-profit SE services were now recruiting students privately. Theses covert activities led to an increase in tuition fees and concerns about schedules and time between tutors. One mother listed her daughter’s routine on a typical Saturday, and it reads like this:

My daughter is preparing for Zhongkao this term, and we have enrolled her in three private tutoring classes on Saturdays from 8am to 4pm. I take her for math tutoring between 8am and 10am, and while she studies with four other kids at the tutor’s home, I go grocery shopping. After that, I take her to the next class in a different location, which usually takes about 30 minutes to drive to. She then works on her English literacy and test skills until 12.30pm. We usually grab some fast food for lunch and head straight to the next class. As far as I know, two-thirds of her classmates are doing the same, if not worse. It’s very tiring, and I feel for her. But as parents, we feel it’s our responsibility to do so.

I need to find a place that offers swimming lessons as it seems to be one of the PE tests that has been included for Zhongkao. And also, I am more concerned about my son’s diet as the policy recommends an ideal ‘height-to-weight ratio’ that students must adhere to. However, it is challenging to maintain this ratio for boys in puberty as they are constantly hungry and require adequate nutrition to support their growth. Sometimes I feel very stressed as I fail to be a good mother.

Discussion

Drawing on Michel Foucault’s conceptualisation of biopower, our study considered how the DRP influenced the conduct of parents and students amidst the sudden shift in China’s SE policies. The DRP is a regulatory apparatus aimed at reshaping expectations and controlling the behaviours of parents and students. By imposing stringent regulations on SE, the Chinese education authority endeavoured to induce a shift in the attitudes and actions of parents, tutors and students. It aimed to divert their attention and resources away from involvement in SE practices. This redirection aimed to alleviate the intense academic competition pressure prevalent among Chinese students. However, our research suggests that the implementation of this policy initiative encountered resistance.

Our data indicated that the DRP achieved limited success in altering the behaviours of parents and students. Certainly, primary school students and their parents significantly reduced their engagement in shadow education due to the constrained options available. However, the entrenched perceptions of academic competition among parents remained largely unaltered. “If the university entrance exam system is not changed, all reforms will only be floating clouds” (Parent in focus group 1, 2022). This suggests that while the policy effectively managed certain behaviours through regulatory measure, it fell short in reshaping the deeper, subjectified beliefs about academic success and competition, highlighting the complexity of fully transforming long-held attitudes of parents and students.

Rather than opting for SE services with big providers, parents began enrolling their children in private tutoring services clandestinely. Despite the DRP aimed to reduce parental expenditure on students’ tuition, the actual outcome looked to be an increase in both tuition fees and the time devoted to attending private classes. In essence, parents in this study adapted their behaviour, but not in alignment with the intended direction envisioned by the regulatory authority. This discovery complements the findings of Abraham et al. (Citation2019), which showed that while parents may no longer be direct recipients of a policy, they will adopt a responsive, albeit non-proactive, stance in navigating policy changes.

Resistance is also a key feature of Foucault’s theorisation of biopolitics and governmentalisation. Foucault (Citation2007) argues that just as there have been forms of resistance to political sovereignty, there must also be forms of resistance to the ways in which power directs people’s conduct. Our data reveal that resistance to the DRP had manifested in various forms, such as parental pushback, alternative educational strategies, and underground tutoring services. Parents’ resistance to the policy shift may be explained by the heightened concerns regarding their children’s academic and career success trajectories, particularly in relation to equitable access to higher education. Their concerns seem to outweigh the power of the state to enforce the new rules. In fact, the imposition of the DRP, intended to discourage participation in SE for a more equitable approach, seems to have inadvertently generated a climate of ambiguity for parents. This ambiguity emanated from concerns about the adequacy of alternative educational avenues, or the effective use of “free time”, in ensuring their children’s academic advancement and future career prospects. One father expressed this concern: “We can’t sit around and doing nothing with the extra time that children are granted now. It would be irresponsible not to plan carefully” (Parent in focus group 2, 2022). The parents’ apprehension aligns with scholarly discussions on parental anxieties in the face of education policy changes and highlights the persistent tension between regulatory interventions and parental decision-making in contemporary Chinese education (Abraham et al. Citation2019; Chen et al. Citation2022). This resistance can be further understood through the lens of biopower (Foucault Citation1997, Citation2006; Leask Citation2012), where the state’s regulatory measures intersect with individual’s strategies to optimise life chances. Foucault’s concept of biopower lends a valuable perspective to understanding how parents, as self-regulating subjects, navigate and resist state-imposed educational policies that they perceive as threats to their children’s future success.

Consequently, the resistance observed in response to the DRP reflects not only a defiance of regulatory measures but also a manifestation of parental concerns rooted in the uncertainties surrounding their children’s educational and professional future. This has not previously been described in Qian, Walker, and Chen’s (Citation2024) three prevailing narratives of DRP. Our data implies that parents may exhibit reduced apprehension from the conventional belief that for-profit capitalised SE operations disrupt China’s social cohesion. In this context, Foucault’s theorisation helps illuminate how parent’s resistance is not merely a reaction to policy changes but a complex negotiation of power relations, personal aspirations, and societal expectations.

Moreover, our study highlights the persistent influence of high-stakes assessments in China, such as the Gaokao and Zhongkao. These exams continue compel parents to seek additional support from tutoring services to enhance their children’s academic performance. The necessity to bridge the void created by the DRP has led parents to position themselves as both the resistors of the policy as well as the conspirators in for-profit education organisations. Parents rejected a “trust and leave it to the school” attitude, indicating a pushback against the aims of the DRP. This resistance can be seen as a quiet but powerful rejection of Xi’s biopower.

Conclusion

This study explored the understanding of parental responses to the DRP and its broader implications for the Chinese education system. We shed light on the resistance strategies Chinese parents adopted in response to the abrupt policy shift. Their resistance to change may be understood because of recent history. Over the previous two decades, SE had entrenched itself as an assumed and integral supplementary component to mainstream schooling in China. Parents from diverse socio-economic backgrounds had consistently turned to these services to enhance their children’s academic success.

In conclusion, we wish to note that in June 2024 as we have been finalising our submission of this paper, China’ education authorities have introduced and reinforced a complementary strategy to the DRP. This strategy, translated as a “Learn First, Pay Later” fee model, mandates implementation by for-profit tutoring providers. Under this model, parents will be surveilled by the government when they transfer funds to a SE provider in the prescribed manner after their child completes an agreed-upon course. According to the Learn First, Pay Later regulation, all SE institutions must now be fully incorporated into a National Off-Campus Education and Training Supervision and Service Comprehensive Platform, which will manage fee structuring across SE to achieve full coverage without gaps. Given this escalation in government monitoring of the SE industry, further research and policy analysis are both warranted and continue to remain timely.

Acknowledgements

The study adhered to all relevant ethical standards, and participant confidentiality and privacy were maintained through the research process. Chinese ethics was granted from Shandong Normal University [2022/ENG]. Then Australian ethical approval [2023/ET000848] for this study was waived by UWA Human Ethics Committee due to the nature of the research involving analysis of existing data from the original Shandong approved study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abraham, Stephanie, Beth A. Wassell, Kathryn McGinn Luet, and Nancy Vitalone-Racarro. 2019. “Counter Engagement: Parents Refusing High Stakes Testing and Questioning Policy in the Era of the Common Core.” Journal of Education Policy 34 (4): 523–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2018.1471161.

- Bray, Mark. 2009. Confronting the Shadow Education System: What Government Policies for What Private Tutoring? Paris: UNESCO.

- Bray, Mark. 2014. “The Impact of Shadow Education on Student Academic Achievement: Why the Research is Inconclusive and What Can be Done About it.” Asia Pacific Education Review 15:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-014-9326-9.

- Bray, Mark. 2022. “Timescapes of Shadow Education: Patterns and Forces in the Temporal Features of Private Supplementary Tutoring.” Globalisation, Societies and Education November:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2143330.

- Chau, David, Joyce Cheng, and Jason Fang. 2021. “China Tries to Spark Baby Boom by Destroying its $140 Billion Tutoring Sector.” ABCNews. August 20. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-20/china-crackdown-private-tutoring/100392352 (Assessed May 1, 2024).

- Chen, Zhiwen. 2023. “Two Common Misunderstandings of ‘General-Vocational’ Division.” China Education Online (Accessed May 4, 2024). https://news.eol.cn/zbzl/202307/t20230704_2450740.shtml.

- Chen, Gaoyu, Mohamed Oubibi, Anni Liang, and Yueliang Zhou. 2022. “Parents’ Educational Anxiety Under the “Double Reduction” Policy Based on the Family and Students’ Personal Factors.” Psychology Research and Behavior Management 15:2067–2082. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S370339.

- Cunningham, Christine, Wei Zhang, Michelle Striepe, and David Rhodes. 2022. “Dual Leadership in Chinese Schools Challenges Executive Principalships as Best Fit for 21st Century Educational Development.” International Journal of Educational Development 89:102531–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102531.

- Dello-Iacovo, Belinda. 2009. “Curriculum Reform and ‘Quality Education’ in China: An Overview.” International Journal of Educational Development 29 (3): 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.02.008.

- Dwyer, Sonya C, and Jennifer L. Buckle. 2009. “The Space Between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (1): 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105.

- Entrich, Steve R, and Wolfgang Lauterbach. 2021. “Fearful Future: The Worldwide Shadow Education Epidemic and the Reproduction of Inequality Outside Public Schooling.” In Theorizing Shadow Education and Academic Success in East Asia, edited by Young Chun Kim, and Jung Hoon Jung, 234–256. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Foucault, Michel. 1997. “Chapt.” In Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth – The Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, edited by Paul Rabinow, 1st ed. New York: New Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 2003. “Chapt.” In Society Must be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76, edited by Bertani Mauro, Alessandro Fontana, and François Ewald. 1st ed. New York: Picador.

- Foucault, Michel. 2006. Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1973–1974, edited by Jacques Lagrange, Francois Ewald, and Alessandro Fontana. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. “Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978.” In Security, Territory, Population, edited by Michel Senellart, Francois Ewald, and Alessandro Fontana. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greenhalgh, Susan, and Edwin A. Winckler. 2005. Governing China’s Population: From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804767217

- Javadi, Yaghoob, and Fakhereh Kazemirad. 2020. “Worldwide Shadow Education Epidemic and Its Move Toward Shadow Curriculum.” Journal of Language Teaching and Research 11 (2): 212–220. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1102.09.

- Kim, Young Chun, and Jung-Hoon Jung2019. Shadow Education as Worldwide Curriculum Studies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kipnis, Andrew B. 2013. “Subjectification and Education for Quality in China.” In Rights, Cultures, Sujects and Citizens, edited by Susanne Brandtstädter, Peter Wade, and Kath Woodward, 289–306. London: Routledge.

- Kwok, Henry. 2023. “Reframing Educational Governance and Its Crisis Through the ‘Totally Pedagogised Society’.” Journal of Education Policy 38 (3): 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2022.2047227.

- Leask, Ian. 2012. “Beyong Subjection: Notes on the Later Foucault and Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 44 (1): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00774.x.

- Li, Cuicui. 2019. “Foucauldian Perspective: Explore Governmentality and Self-Development of China's Shadow Education.” Knowledge Cultures 6 (1): 30–35. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc7120194.

- Liu, Yi-Ling. 2022. “The Larger Meaning of China’s Crackdown on School Tutoring.” The New Yorker. May 16. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-larger-meaning-of-chinas-crackdown-on-school-tutoring (Accessed May 1, 2024).

- Miles, Matthew B, and Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage Publications.

- Ministry of Education of PRC. July 24, 2021. Opinions on Further Reducing the Homework Burden and Off-Campus Training Burden of Students in Compulsory Education. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1778/202107/t20210724_546576.html.

- Newby, Peter. 2014. Research Methods for Education. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Qian, Haiyan, Allan Walker, and Shuangye Chen. 2024. “The ‘Double-Reduction’ Education Policy in China: Three Prevailing Narratives.” Journal of Education Policy 39 (4): 602–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2222381.

- Robinson, Oliver C. 2014. “Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 11 (1): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543.

- Wang, Hai Yan. 2023. “A comparative analysis of double reduction policy in China.” Master diss. Lingnan University.

- Wei, Yi. 2020. “Data Overview: China Institute for Educational Fiance Resarch - Household Survey.” China Institute for Educational Finance Research Brief 5 (184): 1–20.

- Yang, Min, and Ang Ang Chen. 2019. “2018 Parental Satisfaction Survey Report on Reducing Burden of Primary and Secondary School Students.” In Annual Report on China's Education (2019), Edited by Dongping Yang, Min Yang and Shengli Huang, 220–233. Beijing: China:Social Science Literature Publishing House.

- Yang, T., Q. Mok, W. K. Au, Ivan Ka Wai Lai, and Kwan Keung Ng. 2016. “The Acceptance of WeChat Questionnaire Function for Data Collection: A Study in Postgraduate Students in Macau.” Proceedings of International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET): 13-17. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISET38810.2016

- Yung, K. W. H., and Mark Bray. 2017. “Shadow Education: Features, Expansion and Implications.” In Making Sense of Education in Post-Handover Hong Kong: Achievements and Challenges, edited by Thomas Kwan-Choi TSE, and Michael H. Lee, 95–111. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Zhang, Wei, and Mark Bray. 2015. “Shadow Education in Chongqing, China: Factors Underlying Demand and Policy Implications.” Journal of Educational Policy 12 (1): 83–106.

- Zhao, Weili. 2019. “‘Observation’ as China’s Civic Education Pedagogy and Governance: An Historical Perspective and a Dialogue with Michel Foucault.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (6): 789–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1404444.

- Zwier, Dieuwke, Sara Geven, and Herman G. van de Werfhorst. 2020. “Social Inequality in Shadow Education: The Role of High-Stakes Testing.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 61 (6): 412–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715220984500.

Appendices

Appendix 1. WeChat questionnaire

Dear Participant,

We invite you to participate in a survey aimed at understanding parents’ perceptions and the impact of the Double Reduction Policy implemented in China. This policy aims to reduce the excessive burden of homework and off-campus tutoring for students. Your insights will provide valuable information for evaluating the effectiveness of this policy and its implications on students and families. The survey is anonymous, and your responses will be kept confidential. Thank you for your participation.

Section 1: Demographic Information

1. What is your relationship to the student?

o Mother

o Father

o Guardian

o Other (please specify)

2. How many children of yours are attending K-12 schooling?

o 1

o 2

o 3

o More (please specify)

3. What is the grade level of your child(ren)? (Select all that apply)

o Primary school (Grades 1–3)

o Primary school (Grades 4–6)

o Middle school (Grades 7–9)

o High school (Grades 10–12)

4. How much did you spend on before-and-after school tutoring annually before the implementation of the Double Reduction Policy (Yuan)?

o 1000–5000

o 5001–10,000

o 10,001–20,000

o 20,001 and more

5. How much do you spend on before-and-after school tutoring annually after the implementation of the Double Reduction Policy (Yuan)?

o 1000–5000

o 5001–10,000

o 10,001–20,000

o 20,001 and more

6. In which city or province do you reside? (Open-ended)

Section 2: Awareness and Understanding of the Double Reduction Policy

6. How familiar are you with the Double Reduction Policy?

o Very familiar

o Somewhat familiar

o Not very familiar

o Not familiar at all

7. What do you know about the Double Reduction Policy? (Select all that apply)

o Governance of before and after school tutoring or Shadow Education

o Reduction of students’ homework load

o Alleviate educational anxiety

o School-run before and after school services

o Reduce educational cost to families

o Promote education equity

o Reduce examination burden

o Improve students’ well-being

o Reduce the time parents spent on tutoring and grading students’ homework

o Other (please specify)

8. How well do you think the objectives of the Double Reduction Policy reached?

o It achieved the expected result.

o It did not achieve the expected result.

o The situation gets worse than before.

o I don’t know.

Section 3: Perception and Impact of the Double Reduction Policy

9. What are the impacts of the Double Reduction Policy on your child? (Select all that apply)

o No impact; my child continues participating SE as usual

o Yes it has impact; my child reduced time spent on SE now

o Yes it has impact; my child spend more time for SE now

o Other (please specify)

10. What improvements or changes would you suggest for the Double Reduction Policy? (Select all that apply)

o Increase additional learning resources

o Ensure educational resources are fairly distributed

o All schools should implement the Double Reduction Policy at the same pace

o Improve teaching efficiency and teacher’s quality

o Reduce competitiveness in Zhongkao/Gaokao examinations

o The implementation of Double Reduction Policy needs to be supervised

o Other (please specify)

11. What adjustments have you considered as a result of the Double Reduction Policy implementation? (Select all that apply)

o Participating volunteer activities

o Attending practical workshops or activities

o Attending other SE trainings, such as painting, calligraphy, dancing, musical instruments, and acting trainings.

o Attending other SE trainings, such as coding, mathematics competition and English speaking context

o Returning the time back to child

o Other (please specify)

Section 4: Suggestions and Feedback

12. Any additional comments or observations regarding the impact of the Double Reduction Policy? (Open-ended)

Please leave your contact number and email address, if you are willing to participate our face – to – face interview towards end of 2022:

Appendix 2. Double reduction policy study focus groups – questions

How much do you know about the Double Reduction policy?

In your view, do people around you with children of K-12 ages, still want to enroll their children in SE? Is the parents making the decision or the children, in terms of enrollment into SE classes?

After the Double Reduction Policy, have you re-adjusted your expected education outcomes for your children? For example, is passing Zhongkao/Gaokao still be the primary goal for your children? If you adjusted the expectation, can you tell us what is your new goal and why?

How about your children’s education goal? Have you adjusted them for your children because of the Double Reduction policy?

What do you think about Zhongkao and/or Gaokao and their relationship with the Double Reduction policy?

How do you and your children spend the extra free time after the implementation of Double Reduction policy?