Abstract

This research examines the proposal that in Queensland, Australia, the unconventional gas (UG) industry, in accessing landholders’ property, does not solely enter the private land of host farmers, but also the host farmers’ workplace. Thus this industrial activity poses an exacerbation of existing workplace health and safety hazards for host farmers, and introduces new ones. The research identifies there is a clear duty on the UG Companies for the WHS impacts of their undertakings on the host farmer and explores the evidence that shows risk identification and management in relation to host farmers is not in practice routinely considered by the industry or the administering agencies. The report also suggests pathways for further research in order to explore and support host farmers in protecting their livelihoods and families from presently unidentified exposure and contribute to the minimization and prevention of future injuries, disease and fatalities for the host farmers.

Introduction

As detailed by Huth et al. (Citation2018):

Whilst much research has been undertaken into the environmental and economic impacts of Coal Seam Gas (CSG), little research has looked into the issues of coexistence between farmers and the CSG industry in the shared space that is a farm business, a home and a resource extraction network. Much of the land has long been both a family home and a farm business. It is now also becoming host to a large scale resource extraction enterprise. This broad scale CSG development is the first of its kind within the Australian context and so understanding of the issues facing farmers is of great importance.

Overview of the unconventional gas industry in Australia

The unconventional gas industry (UG) involves accessing the Crown-owned petroleum resources (primarily methane gas) trapped in coal/shale underground. The ground under which the resource lies is often privately-owned land (agricultural businesses). In order to access the resource, third parties (UG Companies), on behalf of the government, are given title to explore and produce the resource. These companies, therefore, require access to the privately-owned land. Host farmers do not have any statutory right to refuse the access (Petroleum & Gas (Production & Safety) Act, Citation2004). Access is gained via a land access, conduct and compensation contract (commonly known as a CCA) between the UG company and the host farmer. The CCA focuses on access to private land, which is only a single aspect of what is effectively an existing business and home hosting a third party’s business (Christensen, O’Connor, Duncan, & Phillips, Citation2012; DNRM, Citation2018; Huth et al., Citation2018). Infrastructure is then installed and operated on that privately-owned land by the UG Companies amid the host farmer’s home, family recreational area and business. (Christensen et al., Citation2012; Marinoni & Navarro Garcia, Citation2016; Rijke, Citation2013).

In Australia, UG is a relatively new industry (some 15 years old) but is already big business. Australia is set to become the largest exporter of liquid natural gas (LNG) by 2020 (Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association (APPEA), 2018). According to Business Insider, ‘Australia’s LNG export volumes are forecast to reach 77 Million tonnes in 2018-19, compared to Qatar – currently the world’s largest exporter – who exported 74 million tonnes in 2016’. This also means that gas is set to become the second biggest Australian Resource export by dollar value 2019, overtaking metallurgical coal. The APPEA (Citation2018) Unconventional Gas Activities Report to the peak intergovernmental forum in Australia, Council of Australian Governments (COAG), details that greater than 90% of the Australian unconventional gas production is currently in Queensland (Surat and Bowen Basins) with expansion into other states and regional areas of Queensland imminent as indicated by the Federal Government investing $28 million into a Gas Acceleration Program through the 2017–18 Budget.

Literature review and conceptualisation of research

Developing research in Australia has identified several areas of concern with the impacts of the industry, these include: the nature, content and successional nature of CCAs (Christensen et al., Citation2012); public health impacts (Mactaggart, McDermott, Tynan, & Gericke, Citation2017; Werner, Vink, Watt, & Jagals, Citation2015); human health impacts (Haswell & Bethmont, Citation2016; McCarron, Citation2018); mental health (Morgan, Hine, Bhullar, Dunstan, & Bartik, Citation2016); environmental health, including water quality and air quality; lack of solutions for the toxic waste stream from the industry (LaBouchardiere, Goater, & Beeton, Citation2014); competition for water and land resources (Navi, Skelly, Taulis, & Nasiri, Citation2014; Taylor & Taylor, Citation2016); economic impacts on individuals and communities (Huth et al., Citation2018; Measham, Fleming, & Schandl, Citation2016) and regulatory and enforcement lag and inadequacy (Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal Citation2018; Victoria Auditor General’s Report, Citation2015; Hepburn, Citation2017).

In reviewing the literature on UG, the present Author notes that there is no reference or research data relating to Workplace Health and Safety implications for the host farmer.

The hazards that are identified are in relation to broad environmental impacts, public health and UG worker health and safety and stop short of extrapolating this risk to the WHS for the individual host farmer. The potential for the UG companies to induce hazards or compound existing hazards, through operating amid the host farmers’ workplace; and the resultant legal duties for the UG companies as person in control of the undertaking, to identify, eliminate or minimize those hazards has not been identified or investigated in the literature. This is despite the fact that Safework Australia, in the Australian Safety Strategy (2012–2022), identifies agriculture as already one of the most dangerous industries to work in.

Objectives of research

The objective of the research is to:

establish the host farmers as stakeholders in the CSG Supply Chain;

highlight the need for the administering authority and the industry to consider the WHS implication for farmers hosting UG;

begin to define what the WHS implications are for farmers hosting UG are;

start to fill the gap in the current knowledge; and

contribute to progressing action to address the situation where the nascent industry is creating new, unidentified and unmitigated sources of injury, disease and fatalities for host farmers (now and into the future).

This research also aims to provide additional research pathways such as:

regarding how UG companies address host farmer WHS in Corporate Governance;

assist host farmers to improve their position in the negotiation relationship as unwilling and unrealistic risk-bearers in terms of their lack of control and power in the contractual negotiations that govern UG operations on their land (Christensen et al., Citation2012; Claudio et al., Citation2018; Marinoni & Navarro Garcia, Citation2016; Rijke, Citation2013); and

investigation of fulfilment of the WHS obligations of the State and Commonwealth as issuers of the titles to access and owners of the resource.

Method

The research focused on the State of Queensland, Australia, the most significant area of activity for the UG industry in Australia. The legislation relevant to the research is the Work Health and Safety (WHS) Act, (Qld), the Petroleum & Gas (Production & Safety) Act, (Citation2004) and all subordinate legislative instruments. Although the Environmental Protection Act (Qld) 1994 is also heavily involved in many aspects of the UG industry, and environmental licences are key in gaining government approvals to begin works, this legislation does not address the WHS duties, risks and impacts subject to this research.

Empirical data was obtained through gathering documents and materials from the Queensland regulators’ websites (Office of Industrial Relations – Worksafe Queensland & the Department of Natural Resources, Mines & Energy). The research undertook the following analysis of the material gathered.

Conceptualising the role the host farmer has in UG supply chain.

Memorandum of Understanding and Legislation was analyzed to gain insight into legislative capture and regulator jurisdiction with regard to the host farmer.

Annual Agency compliance and strategy plans were analyzed to determine the level of resources provided to the WHS impacts on the host farmer in terms of engagement, enforcement, inspections and statutory reporting.

Legal enactment of the WHS duties to host farmers was investigated via a search of Australian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) database in terms of prosecutions in the UG industry relating to WHS Duties.

The evidence from the analysis above was applied to a sample of WHS hazards faced by the host famer in an Illustrative Risk Assessment table to further broaden the findings of the analysis.

Through this qualitative examination and contrast, the results identified where the duty to the host farmer is addressed in the legislation and how it is enforced.

Research, analysis & results

Conceptualization of the role of the host farmer in the UG supply chain

To begin the analysis, the first step was to understand how host farmers are represented in the overall administration of the UG Industry.

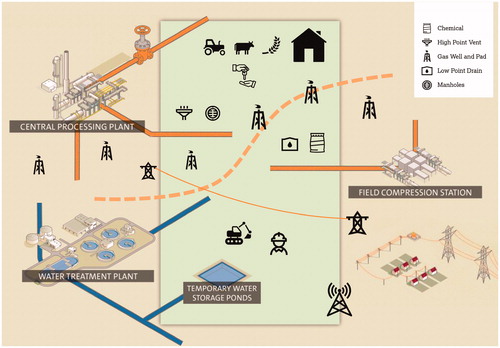

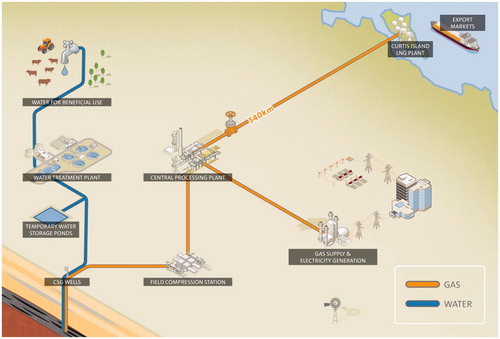

and provide a conceptualization of the interface between the host farmer and the unconventional gas industry in order to contextualize the research. is an image developed by the Department of Natural Resources and Mines (DNRM1, Citation2014) to give an Overview of the CSG Supply Chain. What is missing from this image is the contribution that the host farmer’s workplace makes in the extraction process. The present Author has modified the figure to include the host farmer (). This fundamental change to the figure (showing the host farmer workplace as a physical part of the UG industry supply chain) assists in the conceptualization of the research question and starts to answer the question by indicating how the host farmer is overlooked in the industry footprint by even the administering authority.

Figure 1. Overview of the CSG Supply Chain (DNRM, Citation2014).

Analysis of legislation & jurisdiction

Memorandum of understanding

In Queensland, Workplace Health and Safety Queensland (WHSQ) - Office of Industrial Relations is responsible for work health and safety by enforcing work health and safety laws, investigating workplace fatalities and serious incidents, prosecuting breaches of legislation, educate employees and employers on their legal obligations.

The Queensland Government has determined that separate legislation will be maintained for electrical safety and mining safety.

The DNRME provides support for the safety and health of all Queensland miners and people working in allied industries (including the Petroleum Industry – UG Industry). The department administers associated regulations and recognized standards, guidelines and codes of practice related to mining and petroleum, and energy.

Specifically, regarding the UG industry, host farmers are protected from UG industry impacts on their WHS by nationally uniform WHS laws because unlike the mining industry the WHS Act operates simultaneously with, but does not limit, the P&G Act (Guide to Work Health and Safety Act (Qld), 2015). This circumstance introduces issues since both the WHS Act and the P&G Act apply to the UG industry, and therefore the two jurisdictions can be expected to interact in the field.

Therefore, a Memorandum of Understanding exists between the DNRME (regulates WHS in mining activities) and the Office of Industrial Relations (regulates all other WHS activities in Qld). The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Office of Industrial Relations2 (OIR) and the Department of Natural Resources and Mines (DNRM) (Queensland Government, Citation2017) is made to facilitate cooperation, understanding of roles and responsibilities and foster a co-operative approach to areas of mutual interest (namely UG industry in this case), and allows for the document’s maintenance and review. This document is the guiding force for the day-to-day application of the two main legislative instruments in this research.

The MOU explains that the WHS Act applies to the UG operations in specific circumstances. Those circumstances are detailed in the MOU as:

major hazard facilities (such as the Curtis Island LNG facilities);

construction (such as when the UG Industry create roads and well pads and construction of facilities);

hazardous chemicals (such as any chemicals used in the processing of UG); and

authorized activities (such as the range of activities related to the type of resource authority or grant the government has provided to the UG company (ie Authority to Prospect, Petroleum Lease) for the production, processing and transporting of UG).

This clearly places a duty on the UG companies for the WHS impacts of their undertakings on the host farmer since each of those circumstances, when undertaken within the host farmer’s property, has the potential to impact on the WHS of the host farmer.

However, on the major issue of ‘operating plant’ (the major component of UG installations on host farmers’ properties), the MOU goes on to detail that the P&G Act regulates safety and health for the industry, and that operating plant (other than authorized activities) is explicitly excluded from the WHS Act. Operating plant is defined by the P&G Act (s670) as a ‘facility used to explore for, produce or process petroleum, including machinery used for completing, maintaining, repairing, converting or decommissioning a petroleum well’, and ‘all of the authorized activities for a petroleum authority”.

That is, the MOU initially includes ‘authorized activities’ in the jurisdiction of the WHS Act, and then excludes ‘operating plant’ from the jurisdiction of the WHS Act.

Although the intention of the MOU is to clarify jurisdiction between the departments, it fails to do so. The MOU details a jurisdictional split of WHS matters that favours the P&G Act leaving neither jurisdiction categorically responsible for the UG Industry WHS impacts on the host farmer. This jurisdictional split does not facilitate the enforcement of the duties for the identification, minimization or elimination of the WHS impacts on host farmers.

Legislation

Given the jurisdictional split detailed by the MOU, it is important to understand the objectives of each of the Acts to determine if splitting jurisdiction still fulfils the objectives of the Acts with consideration to WHS impacts on host farmers from the UG industry undertakings.

The object of the Queensland Work Health and Safety Act is to:

secure the health and safety of workers and workplaces by placing a duty on persons in control of business or undertaking to protect workers and other persons against harm to their health, safety and welfare through the elimination or minimisation of risks arising from work or from particular types of substances or plant (Division 2 Section 3 WHS Act).

The objective of the P&G Act is to facilitate and regulate the carrying out of responsible petroleum activities and the development of a safe, efficient and viable petroleum and fuel gas industry, as outlined in Part 2 Section 3 (f, h, j & k) of the P&G Act, in a way that:

ensures petroleum activities are carried on in a way that minimizes conflict with other land uses; and

appropriately compensates owners or occupiers of land; and

facilitates constructive consultation with people affected by activities authorized under this Act; and

regulates and promotes the safety of persons in relation to operating plant. (although this point could refer ‘all persons’, the overwhelming interpretation of ‘persons’ in terms of the rest of the act tends to be skewed to industry staff, contractors, and general public, not the host farmer.)

Whilst interaction of the two acts is complex, the following observations are made:

Host farmers are clearly ‘other persons’ as defined by the Work Health and Safety Act (Qld), and hence are covered by its provisions;

The WHS Act does apply to authorized activities specifically falling under the P&G Act;

The WHS Act does apply to authorized activities; construction activities, electrical, hazardous chemicals and major hazard facilities; and

Relating to the UG operating plant, the P&G Act is to prevail in matters of inconsistency. (Part 2 Division 1 Section 2 WHS Act).

An analysis of the P&G Act in relation to how it addresses WHS showed the majority of the P&G Act details matters related to the administrative management of the P&G Industry. WHS matters are expressively captured in Chapter 9 - Safety in the P&G Act. The name of this chapter and the content does not represent contemporary WHS constructs and standards. This section details obligations in relation to overlaps between the UG industry and Coal Mining but does not identify the overlap with the host farmer’s business. Specifically, the P&G Act s675 (1) (f) specifies that if there is proposed, or there is likely to be, interaction with other operating plant or contractors in the same vicinity, or if there are multiple operating plant with different operators on the same petroleum tenure, risk management and responsibility controls are to be in place. However, the same consideration is not given to the host farmer, yet the likelihood of impact from the UG company activities are just as foreseeable.

Adding further frustration to this aspect is the definition in the P&G Act of a handful of issues as the only legitimate ‘compensatable effects’ of the industry, effectively a limitation of liability that obfuscates the claiming of additional effects such as WHS duties.

Further, the content in Chapter 9 is focused on the implementation of a Safety Management System and details the contents of such a system and the reduction of risk to an ‘acceptable level’ (not contemporary WHS legislative terminology) and does not include a similar expectation to that of the WHS Act: to achieve the identification, elimination and minimization of risks. The Safety Management System described by the P&G Act is also focused on activities within the plant and do not extend to beyond the boundaries of the plant. This approach does not appear to take into consideration the impacts on the host farmer, despite the plant being located literally within the host property, and any impacts from the plant will extend directly into the host farmers’ workplace. Such potential impacts are further explored in the Illustrative Risk Assessment below.

It appears that as the P&G Act has jurisdiction over many aspects of the UG industry operation that gives rise to the potential WHS impacts on host farmers, that the P&G Act does not capture the details and duties as expressed by the WHS Act.

Therefore, the WHS Act does capture the duty that the UG industry owes the host farmer, however, P&G Act does not expressly address the WHS of the host farmer in relation to operating plant and authorized activities.

Analysis of agency compliance plans (inspections, enforcement and prosecutions)

Worksafe Queensland

Worksafe Queensland activities in relation to compliance monitoring and enforcement, inspections, prosecutions and industry interventions and campaigns available on the Worksafe Queensland website were analyzed. Many of these activities were based on, and reference, the Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy 2012–2022 (SafeWork Australia, Citation2012). Analysis of these documents identified that while Agriculture was given attention as a priority industry (SafeWork Australia, Citation2012; Worksafe Qld), there was no identification of the UG industry or its impacts in relation to agriculture specifically or in relation to the other high-risk jurisdictional issues of hazardous chemicals, major hazard facilities, electrical and construction (WHS Act jurisdiction as per the MOU, 2017). That is, even though the high-risk areas are identified in the MOU as WHS Act jurisdiction, Worksafe Qld enforcement, inspection and compliance data did not show any interaction with the UG industry in this regard.

In order to determine if WHS impacts on host farmers were possible and how the duties were being enforced, WHS incidents and Worksafe Qld interactions (as per MOU) with the UG industry were sought.

Data was requested from the Office of Industrial Relations Queensland (Worksafe Qld) (Baker, Citation2018) regarding that department’s interaction with the Queensland UG industry between 2013–2018. The data provided was analyzed with the following results.

17 Event Notifications (statutorily notifiable incidents) relating to UG industry;

8 Dangerous Electrical events (in addition to above, reported to Electrical Safety Office);

3 Inspections;

2 Information and Advisory services;

1 Statutory Notice (Improvement);

2 Non-statutory notices.

Out of the 17 event notifications all were reported by UG companies and none mentioned potential impacts on host farmers, despite an analysis of the descriptions of the incidents reported showing that there were several reports that had easily foreseeable WHS impacts to the host farmers’ workplace. These included:

Falling objects;

Exposure to hazardous gas leak;

Excavation and damage to underground pipe with an associated spill of material;

Electrical fault causing the security fence around the well to be live;

Exposure to a lost radioactive source; and

Unlicensed persons doing electrical work.

These event notifications establish that WHS impacts on the host farmer is a potential risk.

These results indicate a significantly low number of interactions between Worksafe Qld and the UG industry, especially when considered in terms of the period of 5 years and the significance (both financially and spatially) of the UG projects in Qld during that time. Even so, the types of incidents that were reported certainly confirm that there is a risk to host farmers and the duties to address those risks need to be enforced. These results suggest that the execution of the UG industry duties to the host farmer have not been carried out. Therefore, it can be demonstrated that WHS duties owed to the host farmer are not being captured or enforced through the statutory reporting to the responsible agency or the department’s interaction with the industry.

DNRME

In order to determine if the WHS impacts on host farmers were a consideration in the practical activities of the P&G Act enforcing agency, a search for publicly available DNRM Compliance Plans and Reports was undertaken. These reports are produced to outline agency resources and strategies for the coming year in relation to legislative objectives. The search resulted in the following four reports.

Coal Seam Gas Engagement and Compliance Plan 2013 and Report;

CSG engagement and compliance plan report 2015/2016;

Minerals and Energy Resources Compliance Plan Report 2016-17; and

Annual compliance plan for Queensland’s mineral and energy resources 2017–18.

Analysis of the above documents showed the following:

There is no reference to the Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy (AWHSS) 2012–2022;

Reports detail the other agencies that the DNRME work in partnership with, Worksafe Queensland, is not mentioned;

Landholder engagement is described in terms of responding to complaints, no details are provided regarding proactive inspections focussing on WHS for host farmers;

Safety inspections are in relation to the Safety Management System requirements of the P&G Act;

Where the reports outline the planned activities and commitments, no mention is made of the attention to be given to the WHS impacts on host farmers;

The reports discuss extending P&G Act safety activities from the workplace to the ‘consumer and general public’, but no mention of extending their activities to consider the WHS impacts on the host farmer;

The reports discuss compliance strategies that build confidence in safety outcomes for workers within the petroleum and fuel gas industry but only addresses confidence of general public in infrastructure not causing environmental and public health issues, with no reference to building confidence with the host farmer regarding the identification and management of WHS impacts on host farmers.

Search of Australian legal information institute (AustLII) database

In order to determine if the enactment of the legislation as carried out in the courts was capturing the WHS impacts on host farmers, a search of the AustLII Database for prosecutions relating to WHS duties and the UG industry produced the following.

Total of 30 cases that related to UG Industry and WHS Duties;

All cases were relating to employees/contractors within the UG industry;

No cases involving host farmers;

All relating to injuries such as burns, amputations, fractures.

A comparison between statutorily notifiable incidents and prosecutions show a strong tendency for prosecutions to be focussed on actual injury sustained within the UG industry with no prosecutions relating to the types of hazardous events reported through statutory notification where no injury was sustained.

Therefore, it can be demonstrated that WHS impacts for host farmers are not considered, nor is it prioritized and the agency partnership detailed by the MOU is absent. Further, the prosecutions demonstrate that the WHS Act Duties are relevant to the UG industry, but it appears the enforcement of these duties to the host farmer have not yet reached the court, and therefore are not being captured in practice.

Illustrative risk assessment

The findings from the analysis above was applied to a sample of WHS hazards faced by the host farmer in to further broaden the findings of the analysis and answer the final research. The illustrative risk assessment table shows that while WHS duties are owed to the host farmer by the UG industry, the interpreted capture and enactment of the P&G Act routinely frustrates this duty by failing to recognize the interface of the workplaces and eschewing the WHS duties under jurisdictional objectification.

Discussion

The results show that, save the WHS Act, every other element of the data gathered lacked any direct or indirect reference to the key group of ‘host farmers’. WHS impacts do exist for the host farmer but, as identified in the author generated CSG Supply Chain image and the subsequent analysis, the UG Industry WHS impacts on the host farmer have failed to be considered.

Application of contemporary WHS constructs to UG industry missing

Contemporary WHS constructs, the premise of good risk assessment, recent developments in WHS by the National Model WHS legislation, developments in Standards on Safety Management and Risk Management, and even the concept of ‘Safety I vs Safety II’ (Hollnagel et al., Citation2013) shows great evolution in the field. Yet, the P&G Act (as per the evidence regarding Chapter 9) appears to be failing to keep up with contemporary WHS approaches. This is a critical problem that is caused by the government allowing the UG industry to operate under separate legislation with regard to WHS. This situation is the very personification of the theory investigated by Hollnagel et al. (Citation2013), where the work as imagined by the UG industry and the administering authorities is not reflected by the actual work as done and its impacts on the host farmers.

Jurisdictional obfuscation of the issue

When these issues were considered in this research, it showed that the application of the constructs of risk identification and management in relation to WHS of host farmers from the hazards generated by the UG industry is required under the WHS Act, but is not in practice routinely considered by the industry or the administering agencies. It also showed that such constructs and their application are obscured jurisdictionally, which is borne out in the lack of subsequent prosecutions and court actions or the range of other compliance and enforcement activities investigated.

Therefore, in answer to the research question regarding the WHS implications for farmers hosting UG:

UG Industry hazards are addressed in legal duties in the WHS Act;

WHS duties to host farmers by the UG industry is theoretically captured by the WHS Act;

The WHS duties are obscured by the MOU by excluding ‘operating plant’ in favour of the jurisdictionally prevailing P&G Act;

The implementation of the jurisdictional responsibilities in action, (compliance and enforcement activities) indicate the WHS issues for the host farmer are not being captured;

Illustrative risk assessments provide practical examples of the types of WHS issues faced by host farmers and the gaps in the application of jurisdictional enforcement.

Analysis of the MOU and the legislation has highlighted that failing to include the host farmer in the conceptualization of the supply chain of the UG industry has resulted in unclear jurisdictions where neither Worksafe Qld are supporting host farmers in pursuing WHS Act duties of the UG industry to manage their impacts, nor are the DNRME looking outside the UG operation for WHS impacts for the host farmer. This has left a jurisdictional gap where neither enforcing authority capture the host farmer in practice.

It is possible given the illustrative risk assessment, relating to noise and atmospheric exposures particularly, to see the inclusion of the Environmental Protection Act and enforcement of the Environmental Licences as a quasi means of the industry meeting these obligations. However, the Environmental Act and enforcement are not predicated on human impacts and must be pursued by the complainant through nuisance actions where the burden of proof lies with the impacted person. This is clearly not an acceptable solution and only serves to muddy the WHS requirement for the person in control to fulfil duties to those impacted. WHS duties are further legally complicated by the P&G Act’s apparent attempt to limit civil liability through the definition of ‘compensatable effects.’

This theory is further supported by Christensen et al. (Citation2012), LaBouchardiere et al. (Citation2014) and Turton (Citation2015) who raise the point that host landholder, by virtue of being rural and remote, suffer from an issue of visibility in relation to access to justice and resources, choice, cost and experts. This is exacerbated by the fact that the only support that is legislated for the host farmer is that relating to CCA’s, compensation and land access, while the industry traverses ‘jurisdictional issues that are more complex,’ cumulative and overlapping. This is exacerbated by the approach surrounding the nature and content of CCAs which contribute to the poor position of the host farmer. All of this results in failure of the farming community (and those advocating for them) to know, understand and require the WHS duties to be captured and enforced at the interface.

Host farmers missing from the supply chain

The failure to consider the host farmer in the supply chain and the resultant flow-on effects identified in the results, also suggests that the politics of risk and knowledge has a part to play. The illustrative risk assessment table provides an example of the politics of risk and knowledge surrounding the UG Industry that is then embodied in the legislation. That is, there is a perception portrayed by the industry that there is an imaginary (and impenetrable) line between the boundaryless industry footprint and the individual host farmers’ home and workplace. This leads to a situation where the actual lived experience of the host farmer is dismissed and the host farmer is left out of the perceived group of legitimate participants (Espig & de Rijke, Citation2016).

What is a workplace?

Perhaps another contributor to the results of this research is the changing reality of what is a ‘workplace’ influenced by the unique intensity and footprint of the UG industry. That is, there has been a momentous change in the footprint and intensity of the ‘conventional gasfield and processing plant’ in isolated and remote areas, to the UG industry spread across 62 000 km2 of Queensland’s agricultural country (Gasfields Commission, Citation2018) (much of this co-located on host farmer workplaces). Exacerbating this point, for the oil and gas industry, there is a perceived reduced legitimacy of mainstream health and safety regulation for resource industries where there are clear and established long traditions of internal industry risk regulation (Bluff & Johnstone, Citation2017). In other words, the UG industry has inherited the modus operandi of the conventional gas industry thereby having an inadequate appreciation for the unique operational hazards and risks that are created by co-locating heavy industrial activity within an existing business.

Conclusion and ways forward

Returning to the opening quote from Huth et al. (Citation2018), this research contributes to the little researched (but essential) field that considers the risks and impacts of the UG Industry on what is the ‘shared space that is a farm business, a home and a resource extraction network’.

In reviewing the literature on UG, the present Author notes that there is no reference or research data relating to Workplace Health and Safety implications for the host farmer. The potential for UG companies to induce hazards, or compound existing ones, by operating amid the host farmers’ workplace has not been identified or investigated in the previous research. The resultant legal duties for the UG companies (as person in control of the undertaking), to identify, eliminate or minimize those hazards has also not been acknowledged.

When these issues were considered in this research, it showed that the application of the constructs of risk identification and management in relation to WHS of host farmers from the hazards generated by the UG industry is required under the WHS Act, but is not in practice routinely considered by the industry or the administering agencies. It also showed that such constructs and their application are obscured jurisdictionally, which is borne out in the lack of subsequent prosecutions and court actions or the range of other compliance and enforcement activities investigated.

The research findings show that the host farmer is left in a position where she is potentially exposed to WHS risk via the interface with the UG industry, but without a clearly defined path for remedy via the P&G Act, nor clearly defined path of jurisdictional support from the WHS Act.

This research confirms the need for future research and investigation into the WHS issues faced by the host farmer and the WHS obligations of the industry. It confirms the need to (a) identify the hazards, (b) address the associated risks, and (c) enact and enforce the existing WHS obligations on the industry and government.

At its most fundamental level, the host farmers’ right to safe and healthy working conditions is a basic human right assured by the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The UG industry has a significant impact on the host farmer workplace and therefore his WHS. This interface and impacts must be effectively enforced.

Road map for further research and action

Therefore, a pathway forward from this research may include the following:

Review the OIR-DNRM MOU (2017). The document commits to a 3-year review (which is timely at this point) and as detailed in the MOU, the document commits to develop mechanisms to improve the ways the agencies perform. Specifically, the review should establish the legitimate application of WHS duties owed by the UG Industry to the host farmer via undertaking a risk assessment utilizing this research as a basis.

Review the legitimacy of the UG Industry exceptions to the WHS Act in its entirety to resolve the conflicts and gaps created by the duality.

Undertake research on the WHS impacts on host farmers by the UG industry (with host farmers as key stakeholders in the research), with the objective of establishing guidance such as an Approved Code of Practice detailing the way in which this interface may be managed. For example, this guidance material could include:

○How the host farmer should be considered as a key stakeholder in the supply chain;

○How hazard identification and risk management applies to the WHS impact on the host farmer;

○Specific hazards for the host farmer and methods for management;

○How to appropriately consult with the host farmer with regard to potential impacts on their workplace;

○The expectation to include the WHS impacts of the host farmer in statutory documents such as P&G Act Safety Management Plans;

○How WHS duties to the host farmer should be considered in CCA;

○Perhaps allocating the P&G Act prescribed health and safety fee toward this research would assist in resourcing the research and guidance material.

UG Industry review their corporate governance and ensure that the host farmer (with specific consideration to the WHS impacts) is given substantial standing as a key stakeholder.

Investigate the fulfilment of the WHS obligations to the host farmer of the State and Commonwealth as issuers of the titles to access and owners of the resource.

Lawyers and host farmer support network that represent host farmers in negotiations/disputes relating to CCAs ensure that WHS obligations to the host farmer are given legitimacy and WHS experts are utilized to assess and address the issues.

Host farmers and their support network use the existing frameworks (such as statutory reporting, complaints process and setting information expectations with the industry) to bring WHS issues to the fore.

Training and resource allocation for P&G and Worksafe Inspectorate in matters relating to WHS duties owed to host farmers and the induced hazards of the UG industry.

Table A1. Illustrative risk assessment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

Notes

1 Note: the DNRM have recently undergone changes such that they are now known as the DNRME (including Energy). The references retain the old title to be consistent with the reference document.

2 WHS falls under the jurisdiction of the Office of Industrial Relations.

References

- APPEA (2018). Retrieved from: https://www.appea.com.au/oil-gas-explained/benefits/benefits-of-lng/export-revenue/

- Baker, B. ([email protected]), 22 November (2018). Senior Policy Officer. Queensland Office of Industrial Relations. Information provided in response to an emailed information request - Re: Request for information. Email to S. Dougall ([email protected]).

- Bluff, E., & Johnstone, R. (2017). Supporting and enforcing compliance with Australia’s harmonised WHS laws. Australian Journal of Labour Law, 30(1), 30–57.

- Christensen, S., O'Connor, P., Duncan, W.D., & Phillips, A. (2012). Regulation of land access for resource development: a coal seam gas case study from Queensland. Australian Property Law Journal, 21(2), 110–146.

- Claudio, F., De Rijke, K., & Page, A. (2018). The CSG arena: a critical review of unconventional gas developments and best-practice health impact assessment in Queensland, Australia. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 36(1), 105–114. doi:10.1080/14615517.2017.1364025

- Clement Tracol (MSc). 2018. A brief analysis of the UK shale gas industry risk communication. Retrieved from: http://www.academia.edu/37910953/Clement_Tracol_MSc_A_brief_analysis_of_the_UK_shale_gas_industry_risk_communication

- DNRM (2014). Presentation: The Coal Seam Gas (CSG) Industry in Queensland. Presented by Dr. Steve Ward. https://www.ehaqld.org.au/documents/item/725 Accessed 2/8/19

- DNRM (2018). Standard Conduct and Compensation Agreement. Retrieved from: https://www.dnrm.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0006/1395024/standard-conduct-compensation-agreement.doc

- Espig, M., & de Rijke, K. (2016). Unconventional Gas Development and the politics of risk and knowledge in Australia. Energy Research & Social Science, 20, 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.06.001

- Gasfields Commission (2018). Queensland Petroleum and Gas Industry Snapshot, Retrieved 15/5/18 from: http://www.gasfieldscommissionqld.org.au/

- Haswell, M.R., & Bethmont, A. (2016). Health concerns associated with unconventional gas mining in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 16(4), 3825.

- Hepburn, S. (2017). Public resource ownership and community engagement in a modern energy landscape. Pace Environmental Law Review, 34(2), 379–422.

- Hollnagel, E., Leonhardt, J., Shorrock, S., & Licu, T. (2013). From Safety-I to Safety-II. A white paper. Brussels: EUROCONTROL Network Manager. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/australia-natural-gas-exports-growth-2019-2018-1 (accessed 14/7/2018)

- Huth, N.I., Cocks, B., Dalgliesh, N., Poulton, P.L., Marinoni, O., & Garcia, J.N. (2018). Farmers’ perceptions of coexistence between agriculture and a large scale coal seam gas development. Agriculture and Human Values, 35(1), 99–115. doi:10.1007/s10460-017-9801-0

- LaBouchardiere, R.A., Goater, S., & Beeton, R.J.S. (2014). Integrating stakeholder perceptions of environmental risk into conventional management frameworks: Coal seam gas development in Queensland. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 21(4), 359–377. doi:10.1080/14486563.2014.954012

- Mactaggart, F., McDermott, L., Tynan, A., & Gericke, CA. (2017). Exploring the determinants of health and wellbeing in communities living in proximity to coal seam gas developments in regional Queensland. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4568-1

- Marinoni, O., & Navarro Garcia, J. (2016). A novel model to estimate the impact of coal seam gas extraction on agro-economic returns. Land Use Policy, 59(C), 351–365. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.027

- McCarron, G. (2018). Air pollution and human health hazards: A compilation of air toxins acknowledged by the gas industry in Queensland’s Darling Downs. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 75(1), 171–185. doi:10.1080/00207233.2017.1413221

- McKenzie, L., Blair, B., Hughes, J., Allhouse, W., Blake, N.J., Helmig, D., … Adgate, J.L. (2018). Ambient nonmethane hydrocarbon levels along Colorado’s Northern Front Range: Acute and chronic health risks. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52(8), 4514–4525. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b05983

- Measham, T.G., Fleming, D.A., & Schandl, H. (2016). A conceptual model of the socioeconomic impacts of unconventional fossil fuel extraction. Global Environmental Change, 36, 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.12.002

- Morgan, M.I., Hine, D.W., Bhullar, N., Dunstan, D.A., & Bartik, W. (2016). Fracked: Coal seam gas extraction and farmers’ mental health. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47(C), 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.012

- Navi, M., Skelly, C., Taulis, M., & Nasiri, S. (2014). Coal seam gas water: potential hazards and exposure pathways in Queensland. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 25(2), 1–22. doi:10.1080/09603123.2014.915018

- Nothdurft & Anor v QGC Pty Limited & Ors (2017). QLC 41. Retrieved from http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/qld/QLC/2017/41.pdf

- Department of Natural Resources, Mines & Energy, Petroleum & Gas Inspectorate Newsletter. P&G Safety News, November 2018 https://www.vision6.com.au/ch/23788/2ctctmj/2392647/WsNJXNy.Gm.HYyjFo4vu6McU7K.m5ktEhj5zvsSq.html accessed 2/8/19

- Permanent Peoples' Tribunal Session on Human Rights, Fracking and Climate Change, 14–18 May 2018. Advisory Opinon, 2019. http://permanentpeoplestribunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/AO-final-12-APRIL-2019.pdf

- Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act (2004). (Qld) s 564.

- Queensland Government (2017). Memorandum of Understanding between the Office of Industrial Relations and Department of Natural Resources and Mines. https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/82718/mou-oir-and-dept-of-natural-resources-and-mines.pdf Accessed 2/8/19

- Queensland Government Statician's Office (2015). Surat Basin Population Report, 2017. Brisbane: The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) Retrieved 5/8/18 http://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/products/reports/surat-basin-pop-report/surat-basin-pop-report-2017.pdf

- Rijke, K. (2013). The agri‐gas fields of Australia: Black soil, food, and unconventional gas. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 35(1), 41–53. doi:10.1111/cuag.12004

- SafeWork Australia (2012). Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy 2012-2022. Canberra: SafeWork Australia.

- Taylor, M.E., & Taylor, S. (2016). Agriculture in a gas era: a comparative analysis of Queensland and British Columbia's agricultural land protection and unconventional gas regimes. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 22(3), 459–480.

- Turton, D.J. (2015). Unconventional Gas in Australia: Towards a Legal Geography. Geographical Research, 53(1), 53–67. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12101

- Victoria Auditor-General’s Report (2015). Unconventional Gas: Managing Risks and Impacts. Victorian Government Printer.

- Werner, A.K., Vink, S., Watt, K., & Jagals, P. (2015). Environmental health impacts of unconventional natural gas development: A review of the current strength of evidence. Science of the Total Environment, 505(C), 1127–1141. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.084

- Worksafe Queensland (2012). Managing noise and preventing hearing loss at work Code of Practice (PN11160) https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/58176/Noise-preventing-hearing-loss-COP-2011.pdf Accessed 2/8/19

- Worksafe Queensland (2017). Overview of work-related stress. AEU 17/5735 https://1pdf.net/managing-work-related-stress-worksafe-qld_591d54ddf6065de327b8231d Accessed 2/8/19

- Worksafe Queensland (2018). Silica—Identifying and managing crystalline silica dust exposure (PN10121) https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/82806/silica-crystalline-dust.pdf Accessed 2/8/19