ABSTRACT

This literature review focuses on tourism destination competitiveness in the field of sport (TDC sport) or, more specifically, on mapping literature dealing with factors influencing and measuring TDC sport. Existing literature has mainly focused on factors influencing tourism destination competitiveness (TDC) and on measuring TDC in general, paying no attention to two factors: First, there is an emerging line of research and theory building that bridges the fields of leisure, sport, and tourism; and second, when tourism and sport are concerned, generic models in their original form may not be specific enough and some of their dimensions and elements may not be suitable. Thus, this systematic literature analysis (a) focused on TDC in the context of sport, taking into account that sport has unique characteristics, (b) reviewed the current state of empirical research by framing a conceptual model of factors influencing TDC in a sport context, and (c) revealed gaps for future research. Results showed that no single universal set of indicators is applicable to all destinations and issues at all times. Furthermore, approaches in the existing literature have suggested that sport contributes to the construction of a country's brand and provides a unique advantage. Moreover, the analysis highlighted sport-specific factors and addressed the debates about ‘soft’ factors and the notion of a destination as ‘the’ place to be.

Introduction

This literature review focuses on tourism destination competitiveness in the field of sport (hereinafter referred to as TDC sport), i.e. in a sports management/sports tourism context. Thus, the question arises as to whether TDC sport differs from tourism destination competitiveness (hereinafter referred to as TDC) in a more general management/tourism context (Funk, Citation2017). Studying TDC in the very particular context of sport is justified for several reasons. First, it follows the call for more research on sports tourism, which is based on the fact that this is one of the fastest-growing segments of the travel and tourism industry (Hritz & Ross, Citation2010). Second, sport now ranks among the most sought-after leisure experiences in developed countries (Eurostat, Citation2019); and third, sport displays distinct and special features that turn it into a unique business institution (Hess, Nicholson, Stewart, & De Moore, Citation2008; Mangan & Nauright, Citation2000; Smith & Stewart, Citation2010).

One approach to defining TDC sport is to break it down into its constituent parts – competitiveness, tourism, destinations, and sport. The term ‘competitiveness’ refers to ‘how nations and enterprises manage the totality of their competencies to achieve prosperity or profit’ (Bris & Caballero, Citation2015). Tourism is an important generator of economic growth (WTTC, Citation2017); thus, the competitiveness between tourism destinations has substantially increased. Correspondingly, TDC has been assigned numerous definitions – e.g. as a place's ability to optimize its attractiveness for residents and non-residents, to deliver high-quality, innovative, and attractive (in terms of good value for money) tourism services to consumers, and to gain market shares in domestic and global marketplaces, while ensuring that the available resources supporting tourism are used efficiently and sustainably (Dupeyras & MacCallum, Citation2013). As mentioned in the previous paragraph, sport is not another generic business enterprise that is subject to the usual government regulations, market pressures, and customer demands (Gammelsæter, Citation2020). Therefore, the unique characteristics of sport form the basis for TDC sport. In its specific context, TDC sport is defined as a place's ability to optimize its attractiveness for residents and non-residents, to deliver high-quality, innovative, and attractive sports tourism services and to gain market shares in domestic and global marketplaces, while ensuring that the available resources supporting tourism are used efficiently and sustainably; furthermore, the peculiarities of sports tourism are taken into consideration (in accordance with Dupeyras & MacCallum, Citation2013; Flagestad & Hope, Citation2001; Gammelsæter, Citation2020).

All research efforts have faced the same problem: The disagreement over the most effective and rigorous way of measuring destination competitiveness and its factors, stemming from the absence of a widely accepted and clear definition of TDC (Novais, Ruhanen, & Arcodia, Citation2018). Multiple approaches have been employed and resulted in different and often conflicting answers to the three essential questions: What is measured? How is it measured? Who measures it? (Novais, Ruhanen, & Arcodia, Citation2015). Previous research has provided an overview of factors influencing TDC in general (e.g. Crouch, Citation2011; Romão & Nijkamp, Citation2019), but also considered defined perspectives more closely (e.g. Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016; Chin, Thian, & Lo, Citation2017; Chin, Haddock-Fraser, & Hampton, Citation2017). However, it has not specifically explored the factors affecting TDC sport.

Hence, this literature review focuses on TDC sport. More specifically, it provides a systematic literature analysis, which takes a structured, replicable, and transparent approach (David & Han, Citation2004), while summarizing and categorizing existing knowledge (Fisch & Block, Citation2018). This review aims (a) to map the current state of empirical research on the factors influencing TDC sport and (b) to identify gaps in literature requiring future research.

Tourism destination competitiveness (TDC) in the context of sport

Competitiveness originates from the Latin word ‘competer’, which means ‘involvement in business rivalry for markets’ (Bhawsar & Chattopadhyay, Citation2015, p. 7). Academically, the roots of competitiveness studies lie in the international economic theories of Adam Smith and his followers (Bhawsar & Chattopadhyay, Citation2015). Competitiveness frameworks – such as those of Dunning (Citation1993) or D’Cruz and Rugman (Citation1993), to name just a few – have become a paradigm for competitiveness analysis and have been used for empirical research in many fields during the recent decades (Dwyer, Forsyth, & Rao, Citation2000; Enright & Newton, Citation2004; Guan, Yam, Mok, & Ma, Citation2006; Solleiro & Castañón, Citation2005; Zanakis & Becerra-Fernandez, Citation2005).

When we break competitiveness further down to TDC, it is defined as a destination's ability (a) to deliver products and services that perform better than those of other destinations and are superior in satisfying visitor needs (Dwyer & Kim, Citation2003), (b) to offer a high-quality tourism experience (Murphy, Pritchard, & Smith, Citation2000) with the destination product (Pavlović, Avlijaš, & Stanić, Citation2016), (c) to maintain the high productivity of tourism companies (Barros & Alves, Citation2004), and (d) to ensure that these companies arouse tourists’ interest and their demand for various types of destination products (Popesku & Pavlović, Citation2013). Being viewed as competitive by tourists is crucial for the success of a tourism destination (Dwyer & Kim, Citation2003; Mazanec, Wöber, & Zins, Citation2007).

Measuring the competitiveness of destinations has become a dominant theme in tourism research. Various sub-areas have emerged as studies have followed different purposes, such as improving TDC (Crouch & Ritchie, Citation1999; Dwyer & Kim, Citation2003), measuring TDC at a national and regional level (Dwyer, Dragićević, Armenski, Mihalič, & Knežević Cvelbar, Citation2016; Dwyer, Mellor, Livaic, Edwards, & Kim, Citation2004; Enright & Newton, Citation2004; Gomezelj & Mihalič, Citation2008), explaining the relative importance of the various attributes of TDC (Bornhorst, Ritchie, & Sheehan, Citation2010; Caber, Albayrak, & Matzler, Citation2012; Crouch, Citation2011; Dwyer, Cvelbar, Edwards, & Mihalic, Citation2012; Enright & Newton, Citation2005; Fallon & Schofield, Citation2006), and analyzing TDC in the context of sports tourism (Pechlaner, Herntrei, Pichler, & Volgger, Citation2012).

Peculiarities of sport and TDC

According to Funk (Citation2017), there is a lack of studies replicated from other disciplines and extended to fit a sports context. Consequently, the question arises as to whether TDC in a specific sports management/sports tourism context differs from TDC in a general management/tourism context.

Sport has an ambiguous history when viewed from a management perspective. As Stewart and Smith (Citation1999) as well as Smith and Stewart (Citation2010) noted, there are traditionally two contrasting philosophical approaches to the management of sport: One stream sees sport as a unique cultural institution with a host of special features, wherein the reflexive application of standard business practices will not only produce poor management decision making, but also erode the rich history, emotional connections, and social relevance of sport. The other stream views sport as nothing more than just another generic business enterprise that is subject to the usual government regulations, market pressures, and customers’ demands and is therefore best managed by applying standard business tools that assist the planning, financing, human resource management, and marketing functions. Over time, these divisions have been blurred due to the corporatisation of sport and through the emergence of sports management as an academic discipline.

In fact, there are distinct and special features that make sport a unique business institution (Hess et al., Citation2008; Mangan & Nauright, Citation2000; Slack, Citation2003; Smith & Stewart, Citation2010): the intrinsic characteristics of sports products (linked to the uncertainty of outcomes); the fluctuations in supply and demand (resulting from changing sports trends); the intangibility and inconsistent nature of sport; the reliance on product and service extensions; sports customers’ increasing knowledge; and the manner in which sport is consumed in the presence of others (Shilbury, Westerbeek, Quick, Funk, & Karg, Citation2014). All these findings confirm that sport has unique characteristics, underlining that sports management and sports tourism are unique and differ from other business sectors (e.g. Gammelsæter, Citation2020; Szymanski, Citation2009).

TDC sport and factors influencing TDC sport

On the one hand, it should be noted that not all factors that influence the competitiveness of a destination in terms of sport are specific to sport. Literature has shown that general factors, such as financial burden and bureaucracy, transportation connection, and political framework (Happ, Schnitzer, & Peters, Citation2020) as well as the cost of starting up a business, the extent of taxation and administration costs, plus legal certainty at a destination (Ketokivi, Turkulainen, Seppälä, Rouvinen, & Ali-Yrkkö, Citation2017) are very important when making location decisions. That is in accordance with Dwyer et al. (Citation2016), who stated that an important driver of destination competitiveness is the quality of the general infrastructure. In terms of the quality of general infrastructure, costs as well as burden and bureaucracy, sports businesses do not differ from other businesses in their choice of location (Happ, Citation2020).

On the other hand, scholarly literature has neglected various points in relation to TDC sport: identifying new competitiveness factors and indicators that are specific to particular countries and situations (Crouch, Citation2007, Citation2008; Crouch & Ritchie, Citation1999; Dwyer et al., Citation2004; Gooroochurn & Sugiyarto, Citation2005); examining competitiveness and foreign location choices that go beyond multiple disciplinary boundaries (Kim & Aguilera, Citation2016); and boosting the frequently underrepresented position of TDC sport and sport tourism (Higham & Hinch, Citation2009). It should be highlighted that there are indeed factors specific to sport (Happ, Citation2020; Happ et al., Citation2020). Happ et al. (Citation2020), for example, found that there are sport-specific critical soft factors influencing location decisions of companies in the sports manufacturing industry, such as the image of the location in terms of sport, quality of life in terms of sport, and work attitude and population, also in terms of sport. In the context of this literature review, soft factors are defined as non-structural organizational characteristics, such as shared values and employees’ behaviour (Homburg, Fassnacht, & Güenther, Citation2003).

Researchers have attempted to find answers to the question of ‘What factors influence TDC and how can it be measure?’ (Goffi & Cucculelli, Citation2019), while underscoring the point that TDC cannot be understood or measured by a few determinants; in addition, several research approaches have proposed potential factors that can influence competitiveness. Reisinger, Michael, and Hayes (Citation2019) grouped various determinants of destination competitiveness into three different categories: (a) inherited and capitalizable determinants (e.g. natural environment, culture and history, location and market ties, landscape, climate, fauna and flora, food, traditions, music and events, hospitality of locals, and human and capital resources); (b) created and manageable determinants (e.g. activities, special events, entertainment, shopping, hotels, restaurants, general infrastructure, security and safety as well as facilitating resources, such as visas and education, destination management, and marketing); and (c) external and adaptable determinants (e.g. macro or global environment including political, economic, demographic, technological, natural, and cultural factors).

The aim of this literature review is: to map the current state of empirical research on the factors influencing TDC sport.

The knowledge from literature has shown that there are general factors (e.g. general infrastructure factors) and specific factors (e.g. in the area of sport) that shape the competitiveness of a destination. This led us to addressing the research question of this literature review in a complex way, i.e. by including sport-specific TDC literature and general TDC literature in terms of influencing factors of competitiveness.

Methods

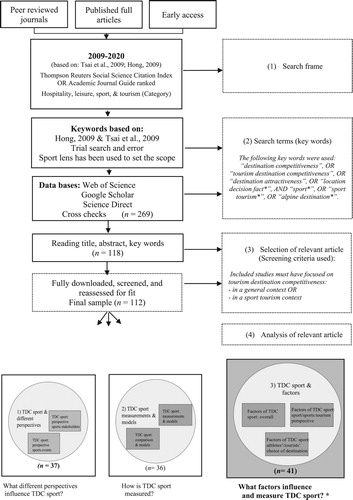

This paper provides a systematic literature analysis that follows a structured, replicable, and transparent approach (David & Han, Citation2004), summarizing and categorizing existing knowledge in terms of TDC sport (Fisch & Block, Citation2018). It includes articles working with various methodologies, i.e. quantitative, qualitative, mixed, and conceptual approaches (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). Using a systematic procedure, we applied transparent and rigorous search criteria. Thus, it was possible to provide an in-depth overview of the existing research and the concepts relating to TDC sport. Moreover, this literature review required a process-oriented procedure (David & Han, Citation2004; Fisch & Block, Citation2018) and hence was based on four phases, which are explained in .

Figure 1. Flowchart of systematic literature review and article selection. *TDC sport & factors: focus of this systematic literature review.

As shown in , this literature research underwent four phases: The definition of a search frame (Phase 1) and the definition of search terms (Phase 2), which was followed by the selection of relevant articles (Phase 3) and their analysis (Phase 4). The procedures for Phases 1 and 2 are mapped in the flowchart, whereas Phases 3 and 4 demand a more detailed explanation.

Within Phase 3 – the selection of relevant articles – the derived sample of 269 articles was doublechecked for relevance by reading title, abstract, and keywords. Articles with a missing scope (Newbert, Citation2007) and articles that determined that TDC and TDC sport were not their key themes were neglected. In total, 151 articles were excluded. The remaining 118 articles were downloaded, fully screened, and reassessed for fit, resulting in the final sample of n = 112. Appendix 1 consists of an overview including author, title, year, and journal of the included articles.

For the further analysis, the articles were grouped into three main topics as suggested in the literature (Goffi & Cucculelli, Citation2019; Jin & Weber, Citation2016; Novais et al., Citation2015):

TDC sport & different perspectives (sports events, sports stakeholders) (n = 37);

TDC sport measurements & models (measurements & models, comparison & models) (n = 36);

TDC sport & factors (overall, sport/sports tourism perspective, athletes’/tourists’ choice of destination) (n = 42 reduced to n = 39 after detailed analysis).

Within Phase 4 – the analysis of relevant articles – 42 articles were fully screened and reassessed for fit, resulting in the final sample of n = 41. The final 41 articles were analysed based on an open-coding approach (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005) in MaxQDA. All articles were grouped into three large thematic approaches within the topic TDC sport & factors: overall; sport/sports tourism perspective; and athletes’/tourists’ choice of destination. Including literature reviews (see Appendix 2), a total of 13 codes were assigned; each article was screened completely, and individual text passages were assigned to the codes. Appendix 2 provides a table containing information about the author(s), year, method, subject, context, issue, overall outcome, outcome factors, title, and journal.

Key themes in the literature reviewed: TDC sport & factors

A sample of n = 41 studies in the field of TDC sport & factors were analysed: The majority (59%; n = 24) of them used a quantitative study design, 10% (n = 4) applied a mixed approach, 18% (n = 8) were based on a qualitative study design, and 13% (n = 5) applied a conceptual design.

The results showed that no single universal set of indicators is applicable to all destinations and issues at all times. However, approaches in the existing literature have suggested that sport contributes to the creation of a country's brand and provides a unique advantage. The literature's understanding that there are general factors (e.g. general infrastructure: Dwyer et al., Citation2016) and specific factors (e.g. in the area of sport: Happ et al., Citation2020) that determine the competitiveness of a destination led us to answer the research question of this literature review in a complex way. Firstly, general literature on factors influencing TDC was used for the first group (TDC sport & factors: overall) to provide a comprehensive overview of the factors affecting TDC in general and TDC sport in particular. Secondly, two specific categories were created (TDC sport & factors: sport/sports tourism perspective and TDC sport & factors: athletes’/tourists’ choice of destination), into which the sport-specific literature was placed.

In an attempt to map previous research results, were created to show the highlights of the factors influencing TDC sport. The exact references that provide the basis for these tables are shown in Appendices 3–5.

Table 1. Highlights of outcome factors of TDC sport: overall.

Table 2. Highlights of outcome factors of TDC sport: sports events/sports tourism perspective.

Table 3. Highlights of outcome factors of TDC sport: athletes’/tourists’ choice of destination.

Results on factors of TDC sport: overall

Previous research has provided valuable insights into the overall factors influencing TDC and TDC sport. A total of 16 studies based on different TDC models were investigated to map the overall factors. shows a summary of the results (for more details refer to Appendix 3).

Results on factors of TDC sport: perspective sports tourism & sports events

Research in this area allowed important insights into factors influencing TDC sport from a sports tourism and sports event point of view. In total, 13 studies were analysed; they can be assigned to winter tourism, summer tourism, and other studies, as depicted in (for more details refer to Appendix 4).

Results on factors of TDC sport: athletes’/tourists’ choice of destination

provides valuable insights into the factors influencing destination selection from a visitor's point of view. Here, one has to differentiate between athletes and active sports tourists: Their choice of destination and thus their perceived TDC sport is affected by factors they both have in common and by factors that are distinctive for certain groups. Five studies on runners, bikers, and golfers have found various factors influencing active sports tourists in their selection of a destination. Two studies have shown factors affecting athletes (endurance athletes and marathon runners) in choosing their desired surrounding field (for more details refer to Appendix 5).

Discussion

Unlike competitiveness in other industries, destination competitiveness and TDC do not refer to a single, well-defined product or service but to an overall experience (Murphy et al., Citation2000). This ‘total experience’ (Dwyer et al., Citation2004) is produced by a variety of destination stakeholders, who contribute to the visitor experience, including tourism enterprises, residents, other supporting industries, destination management organisations (DMOs), and the public sector (Crouch, Citation2011). This ‘fuzzy’ notion of the destination further complicates the unit of analysis and thus the measurement of destination competitiveness (Claver-Cortés, Molina-Azorín, Pereira-Moliner, & López-Gamero, Citation2007). Breaking down TDC to TDC sport does not necessarily unravel the complexity. The discussion is an ongoing topic in tourism and sports tourism research, and the call for more research in this area has been aiming for more and deeper insights.

This systematic research-based analysis shows the importance of what Morgan, Pritchard, and Pride (Citation2011) described as ‘soft’, less tangible factors. With these ‘soft’ factors a destination can differentiate itself from others and solidify its brand image, whereas ‘hard’, more tangible factors – such as infrastructure, accessibility, quality of facility, price and cross price elasticity, sporting services, restaurants, social life, and financial incentives – are clearly important in attracting sports groups (Komppula & Laukkanen, Citation2016; Morgan et al., Citation2011). The findings of Pouder, Clark, and Fenich (Citation2018) confirmed that also more nuanced factors play a key role to that end. Notable in this regard are destinations that are recognized as good host communities for offering exceptional services, which are provided by DMO staff or trained volunteers. These destinations enjoy a branded reputation of being ‘the’ place to go for a particular sport (Pouder et al., Citation2018; Happ, Citation2020; Happ et al., Citation2020). As Morgan et al. (Citation2011) noted, place reputation has become the key to competitiveness. Hence, ‘soft’ factors are crucial and part of the framework for TDC and TDC sport, and they should be taken seriously – even if a destination cannot specify them well enough (Happ, Citation2020; Happ et al., Citation2020).

The findings have shown that TDC sport is affected by the overall factors influencing TDC – e.g. accessibility (Lee & Huang, Citation2014) and price (Komppula & Laukkanen, Citation2016) – but also by sport-specific factors, such as a fun, comfortable atmosphere and the image domain in terms of sport (skiing) as well as a classy atmosphere (Kim & Perdue, Citation2011), the attractiveness of a sport destination, sport route quality, and natural tourism resources (Lee & Huang, Citation2014), the possibility to have a new sport experience every time (Getz & McConnell, Citation2011), and the natural ecology and beautiful scenery (Lee & Huang, Citation2014). A topic that is currently very present in media and science is climate change. Accordingly, the factor of sufficient snow coverage as a key attribute when dealing with competitiveness in Alpine winter sports destinations has been discussed (Bausch & Unseld, Citation2018). In other words, there are specific factors influencing TDC sport, and these factors need to be considered when talking about TDC sport and the competitiveness of destinations.

Moreover, the findings highlighted that the models and measurements used to frame TDC sport (e.g. Hallmann, Müller, & Feiler, Citation2014; Zehrer, Smeral, & Hallmann, Citation2017) were mainly based on Ritchie and Crouch (Citation2003) and Porter (Citation1990). Regarding competitiveness of winter sports destinations, subjective performance measures have been added to previous research (Andrades-Caldito, Sánchez-Rivero, & Pulido-Fernández, Citation2014), mostly either from a demand or supply side (e.g. Crouch, Citation2011; Enright & Newton, Citation2004; Hallmann et al., Citation2014; Hudson, Ritchie, & Timur, Citation2004; Ritchie & Crouch, Citation2003). Accordingly, Hallmann et al. (Citation2014) amended special indicators to the model of Ritchie and Crouch (Citation2003), capturing the characteristics of winter sports tourism (e.g. price for a lift ticket referring to value for money as in Gomezelj & Mihalič, Citation2008 or snow conditions as in Bausch & Unseld, Citation2018). All indicators fitted consequently into the categories of the model's five dimensions. Yet, not all factors proposed by Ritchie and Crouch’s (Citation2003) dimension were investigated in the context of winter sports tourists (e.g. political will was excluded) (Hallmann et al., Citation2014). It has become obvious that diverse models build the base for TDC sport research, but they need to be extended and adapted to the specific case; moreover, there are still lacks in know-how.

In contrast to the aforementioned models based on the demand and supply point of view, studies from a tourists’ point of view have applied different models and approaches. Looking more deeply into the phenomenon of active sports tourists, Gibson (Citation2002), Weed (Citation2006), and Humphreys and Weed (Citation2014) based their research on the development of grounded theory, both methodically and theoretically, and called for further research. One can summarize that there is not only one model measuring TDC sport and its neighbouring fields; for each situation and destination different approaches build the base for research, and that is what makes this field of research complex and exciting at the same time.

The findings emphasized the great potential of sports tourism and TDC sport. Sport and tourism have grown significantly to become important economic (Gaffney, Citation2010; Smith, Citation2014; Tichaawa & Swart, Citation2010) and social activities (Hall, O’Mahony, & Gayler, Citation2017). Sport and tourism are now among developed countries’ most sought-after leisure experiences. They are highly valued and prestigious due to the fact that tourism is a trillion-dollar industry and sport is a multi-billion-dollar industry with both having become a dominant force in the lives of millions of people globally (Kurtzman, Citation2005). Research on TDC sport has predominantly discussed winter tourism with a focus on different types of winter sports and snow-based activities in related resorts. However, there is a lack of research on winter tourism as a general phenomenon (Pouder et al., Citation2018). Winter tourists belong to a higher income group than summer guests (Alpine Convention, Citation2013). The typical winter tourist is sport- and fun-oriented and younger than other tourists, and mostly, the winter sport vacation is the second or third vacation of the year (Alpine Convention, Citation2013). Furthermore, winter tourists are less influenced by economic fluctuations than summer tourists (Zehrer et al., Citation2017). These facts inevitably led to a discussion about the factors affecting summer and winter tourists and the differences arising between the two target groups: Is it one and the same person who has different travel habits in summer, or is there a difference between summer sports tourists and winter sports tourists visiting the same region? Which factors influence the TDC sport of the respective target groups in winter and summer?

In addition, the findings highlighted that sports tourism consumers (active sports tourists or athletes) follow Maslow's hierarchy (Maslow, Citation1970): Their basic needs (in particular physiological needs) are fulfilled, and individuals are striving for self-actualization during their vacations (Hallmann et al., Citation2014). The consumer expects fun, a range of options, and unique experiences (e.g. Preglau, Citation2001). Nevertheless, we have to distinguish between two types of sports tourism consumers – athletes and active tourists – and consequently between their respective competitiveness factors for TDC sport (for athletes see Aicher & Newland, Citation2018; Newland & Aicher, Citation2018; for active tourists see Jun et al., Citation2017; Zehrer et al., Citation2017). For example, the quality of the sports experience and sports entertainment were important for active sports tourists (Aicher & Newland, Citation2018); by contrast, athletes minded the reputation and prestige of the event, having a new event experience every time, and playing to the limit (Getz & McConnell, Citation2011; Recours, Souville, & Griffet, Citation2004). After all, there are differences, and this know-how can help managers to provide specific offers for each target group.

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

The constructs TDC and TDC sport are very complex, experts have even discussed about the definition. Above all, the influence of sport-specific factors affecting TDC is an important topic – especially given the economic power of the sports and tourism industry. In addition, the differences within the various sub-sectors in sport (e.g. athletes or active sports tourists; winter tourists or summer tourists; different perspectives of sports stakeholders; new sports trends) have to be considered and will provide research with new challenges. The findings of this literature review will enable a better understanding of which factors influence TDC sport and the surrounding framework and how. Additionally, this literature analysis revealed the valuable, but compared to TDC overall frequently underrepresented position of TDC sport and sports tourism (Higham & Hinch, Citation2009).

As any study, also this systematic literature analysis has some limitations. First, the assessment of the studies (e.g. the categorization of approaches and definition of search terms) was carried out by only one person. Second, no quality assessment of the investigated studies was included in this review. Third, the review did not include edited books. Nevertheless, this analysis allows relevant implications for the future.

Main areas of future research could be derived from the following topics: (a) the increasing importance of sports tourism (e.g. Hallmann et al., Citation2014); (b) factors influencing TDC and the attractiveness of destinations (e.g. Zehrer et al., Citation2017); (c) models framing this research (e.g. Ritchie & Crouch, Citation2003); and (d) the notion that sport is unique (Smith & Stewart, Citation2010). It is important that destinations more strongly reflect on factors affecting their competitiveness while considering their given unique selling proposition. Although more research on specific factors influencing TDC and TDC sport can lead to significantly increased competitiveness, there is general acceptance within the literature that destinations can improve competitiveness by understanding the influence of tangible and intangible destination attributes (Hudson et al., Citation2004). All in all, there is ample scope for destinations to act and develop.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aicher, T. J., & Newland, B. L. (2018). To explore or race? Examining endurance athletes’ destination event choices. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(4), 340–354.

- Akis, S., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17(7), 481–494.

- Alpine Convention. (2013). Sustainable tourism in the Alps: Report on the state of the Alps. Alpine signals—special edition 4. Retrieved from http://www.alpconv.org/en/AlpineKnowledge/RSA/tourism/Documents/RSA420en20WEB.pdf?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- Andrades-Caldito, L., Sánchez-Rivero, M., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2014). Tourism destination competitiveness from a demand point of view: An empirical analysis for Andalusia. Tourism Analysis, 19(4), 425–440.

- Azzopardi, E., & Nash, R. (2016). A framework for island destination competitiveness–perspectives from the island of Malta. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(3), 253–281.

- Barros, C. P., & Alves, F. P. (2004). Productivity in the tourism industry. International Advances in Economic Research, 10(3), 215–225.

- Bausch, T., & Unseld, C. (2018). Winter tourism in Germany is much more than skiing! consumer motives and implications to Alpine destination marketing. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(3), 203–217.

- Bhawsar, P., & Chattopadhyay, U. (2015). Competitiveness: Review, reflections and directions. Global Business Review, 16(4), 665–679.

- Bornhorst, T., Ritchie, J. B., & Sheehan, L. (2010). Determinants of tourism success for DMOs & destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders’ perspectives. Tourism Management, 31(5), 572–589.

- Bris, A., & Caballero, J. (2015). Revisiting the fundamentals of competitiveness: A proposal. IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook. IMD World Competitiveness Center.

- Caber, M., Albayrak, T., & Matzler, K. (2012). Classification of the destination attributes in the content of competitiveness (by revised importance-performance analysis). Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(1), 43–56.

- Chin, W. L., Haddock-Fraser, J., & Hampton, M. P. (2017). Destination competitiveness: Evidence from Bali. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(12), 1265–1289.

- Chin, C. H., Thian, S. S. Z., & Lo, M. C. (2017). Community’s experiential knowledge on the development of rural tourism competitive advantage: A study on Kampung Semadang–Borneo Heights, Sarawak. Tourism Review, 72(2), 238–260.

- Claver-Cortés, E., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Pereira-Moliner, J., & López-Gamero, M. D. (2007). Environmental strategies and their impact on hotel performance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 663–679.

- Crouch, G. I. (2007). Modelling destination competitiveness. A survey and analysis of the impact of competitiveness attributes. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 27–45.

- Crouch, G. I. (Ed.). (2008). Tourism and hospitality research, training and practice: “Where the bloody hell are we?”. Proceedings of the 18th Council for Australian University Tourism and Hospitality, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia.

- Crouch, G. I. (2011). Destination competitiveness: An analysis of determinant attributes. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 27–45.

- Crouch, G. I., & Ritchie, J. B. (1999). Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 137–152.

- David, R. J., & Han, S. K. (2004). A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strategic Management Journal, 25(1), 39–58.

- D’Cruz, J. R., & Rugman, A. M. (1993). Developing international competitiveness: The five partners model. Business Quarterly, 58(2), 60–72.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Dunning, J. H. (1993). Internationalizing Porter’s diamond. Management International Review, 33(2), 7.

- Dupeyras, A., & MacCallum, N. (2013). Indicators for measuring competitiveness in tourism: A guidance document (OECD Tourism Papers, 2013/02). OECD Publishing.

- Dwyer, L., Cvelbar, L. K., Edwards, D., & Mihalic, T. (2012). Fashioning a destination tourism future: The case of Slovenia. Tourism Management, 33(2), 305–316.

- Dwyer, L., Dragićević, V., Armenski, T., Mihalič, T., & Knežević Cvelbar, L. (2016). Achieving destination competitiveness: An importance–performance analysis of Serbia. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(13), 1309–1336.

- Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Rao, P. (2000). The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: A comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management, 21(1), 9–22.

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414.

- Dwyer, L., Mellor, R., Livaic, Z., Edwards, D., & Kim, C. (2004). Attributes of destination competitiveness: A factor analysis. Tourism Analysis, 9(1–2), 91–101.

- Enright, M. J., & Newton, J. (2004). Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tourism Management, 25(6), 777–788.

- Enright, M. J., & Newton, J. (2005). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in Asia Pacific: Comprehensiveness and universality. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 339–350.

- Eurostat. (2019). E-commerce statistics for individuals. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/data/database

- Fallon, P., & Schofield, P. (2006). The dynamics of destination attribute importance. Journal of Business Research, 59(6), 709–713.

- Fisch, C., & Block, J. (2018). Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68(2), 103–106.

- Flagestad, A., & Hope, C. A. (2001). Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value creation perspective. Tourism Management, 22(5), 445–461. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00010-3

- Funk, D. (2017). Introducing a sport experience design (SX) framework for sport consumer behaviour research. Sport Management Review, 20(20), 145–158.

- Gaffney, C. (2010). Mega-events and socio-spatial dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919–2016. Journal of Latin American Geography, 9(1), 7–29.

- Gammelsæter, H. (2020). Sport is not industry: Bringing sport back to sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly. doi:10.1080/16184742.2020.1741013

- Getz, D., & McConnell, A. (2011). Serious sport tourism and event travel careers. Journal of Sport Management, 25(4), 326–338.

- Gibson, H. J. (2002). Sport tourism at a crossroad? Considerations for the future. In S. Gammon & J. Kurtzman (Eds.), Sport tourism: Principles and practice (pp. 111–122). Eastbourne: LSA.

- Goffi, G., & Cucculelli, M. (2019). Explaining tourism competitiveness in small and medium destinations: The Italian case. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(17), 2109–2139.

- Gomezelj, D. O., & Mihalič, T. (2008). Destination competitiveness—Applying different models, the case of Slovenia. Tourism Management, 29(2), 294–307.

- Gooroochurn, N., & Sugiyarto, G. (2005). Competitiveness indicators in the travel and tourism industry. Tourism Economics, 11(1), 25–43.

- Guan, J. C., Yam, R. C., Mok, C. K., & Ma, N. (2006). A study of the relationship between competitiveness and technological innovation capability based on DEA models. European Journal of Operational Research, 170(3), 971–986.

- Hall, J., O’Mahony, B., & Gayler, J. (2017). Modelling the relationship between attribute satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and behavioural intentions in Australian ski resorts. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 764–778.

- Hallmann, K., Müller, S., & Feiler, S. (2014). Destination competitiveness of winter sport resorts in the Alps: How sport tourists perceive destinations? Current Issues in Tourism, 17(4), 327–349.

- Happ, E. (2020). Location decisions of sport manufacturing businesses in tourism destinations – analyzing factors of attractiveness. Current Issues in Sport Science (CISS). doi:10.15203/CISS_2020.006

- Happ, E., Schnitzer, M., & Peters, M. (2020). Sport-specific factors affecting location decisions in business to business sport manufacturing companies: A qualitative study in the Alps. International Journal of Sports Management and Marketing.

- Hess, R., Nicholson, M., Stewart, B., & De Moore, G. (2008). A national game: The history of Australian Rules football. Melbourne: Viking Penguin.

- Higham, J., & Hinch, T. (2009). Sport and tourism: Globalization, mobility and identity. Amsterdam: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Homburg, C., Fassnacht, M., & Güenther, C. (2003). The role of soft factors in implementing a service-oriented strategy in industrial marketing companies. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 10(2), 23–51.

- Hritz, N., & Ross, C. (2010). The perceived impacts of sport tourism: An urban host community perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 24(2), 119–138.

- Hudson, S., Ritchie, B., & Timur, S. (2004). Measuring destination competitiveness: An empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 1(1), 79–94.

- Humphreys, C. J., & Weed, M. (2014). Golf tourism and the trip decision-making process: The influence of lifestage, negotiation and compromise, and the existence of tiered decision-making units. Leisure Studies, 33(1), 75–95.

- Jin, X., & Weber, X. (2016). Exhibition destination attractiveness – organizers’ and visitors’ perspectives. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(12), 2795–2819.

- Jun, S. Y., Walker, A. M., Kim, H., Ralph, J., Vermerris, W., Sattler, S. E., & Kang, C. (2017). The enzyme activity and substrate specificity of two major cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), SbCAD2 and SbCAD4. Plant Physiology, 174(4), 2128–2145.

- Kennelly, M., & Toohey, K. (2014). Strategic alliances in sport tourism: National sport organisations and sport tour operators. Sport Management Review, 17(4), 407–418.

- Ketokivi, M., Turkulainen, V., Seppälä, T., Rouvinen, P., & Ali-Yrkkö, J. (2017). Why locate manufacturing in a high-cost country? A case study of 35 production location decisions. Journal of Operations Management, 49-51, 20–30.

- Kim, J. U., & Aguilera, R. V. (2016). Foreign location choice: Review and extensions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(2), 133–159.

- Kim, D., & Perdue, R. R. (2011). The influence of image on destination attractiveness. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(3), 225–239.

- Kim, N., & Wicks, B. E. (2010). Rethinking tourism cluster development models for global competitiveness. International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track, Event (28). Retrieved from http://scholarworks.umass.edu/refereed/CHRIE_2010/Friday/28

- Komppula, R., & Laukkanen, T. (2016). Comparing perceived images with projected images-A case study on Finnish ski destinations. European Journal of Tourism Research, 12, 41–53.

- Kurtzman, J. (2005). Economic impact: Sport tourism and the city. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 10(1), 47–71.

- Lee, C. F., & Huang, H. I. (2014). The attractiveness of Taiwan as a bicycle tourism destination: A supply-side approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(3), 273–299.

- Liu, J. C., Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1987). Resident perception of the environmental impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 14(1), 17–37.

- Mangan, J. A., & Nauright, J. (2000). Sport in Australasian society. Past and present. London: Frank Cass Publishers.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Mazanec, J. A., Wöber, K., & Zins, A. H. (2007). Tourism destination competitiveness: From definition to explanation? Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 86–95.

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2011). Destination brands: Managing place reputation. London: Routledge.

- Murphy, P., Pritchard, M. P., & Smith, B. (2000). The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management, 21(1), 43–52.

- Newbert, S. L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 121–146.

- Newland, B. L., & Aicher, T. J. (2018). Exploring sport participants’ event and destination choices. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 22(2), 131–149.

- Novais, M. A., Ruhanen, L., & Arcodia, C. (2015). Tourism destination competitiveness: Proposing a framework for measurement. In Proceedings of CAUTHE 2015: Rising tides and sea changes: Adaptation and innovation in tourism and hospitality. Australia: School of Business and Tourism, Southern Cross University.

- Novais, M. A., Ruhanen, L., & Arcodia, C. (2018). Destination competitiveness: A phenomenographic study. Tourism Management, 64, 324–334.

- Pavlović, D., Avlijaš, G., & Stanić, N. (2016). Tourist perception as key indicator of destination competitiveness. TEME: Casopis Za Društvene Nauke, 40(2), 853–868.

- Pechlaner, H., Herntrei, M., Pichler, S., & Volgger, M. (2012). From destination management towards governance of regional innovation systems – the case of South Tyrol, Italy. Tourism Review, 67(2), 22–33.

- Popesku, J., & Pavlović, D. (2013). Competitiveness of Serbia as a tourist destination: Analysis of selected key indicators. Marketing, 44(3), 199–210.

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Pouder, R. W., Clark, J. D., & Fenich, G. G. (2018). An exploratory study of how destination marketing organizations pursue the sports tourism market. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 184–193.

- Preglau, M. (2001). Industrieerlebniswelten – Erlebnisgesellschaft: Der soziokulturelle Hintergrund [Industrial experience worlds – event society: The socio-cultural background]. In H. Hinterhuber, H. Pechlaner, & K. Matzler (Eds.), Industrieerlebniswelten. Vom Standort zur Destination [Industrial experience worlds. From location to destination] (pp. 59–68). Berlin: ESV.

- Recours, R. A., Souville, M., & Griffet, J. (2004). Expressed motives for informal and club/association-based sports participation. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(1), 1–22.

- Reisinger, Y., Michael, N., & Hayes, J. P. (2019). Destination competitiveness from a tourist perspective: A case of the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 259–279.

- Ritchie, J. R. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. Oxon: CABI Publishing.

- Romão, J., & Nijkamp, P. (2019). Impacts of innovation, productivity and specialization on tourism competitiveness – a spatial econometric analysis on European regions. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(10), 1150–1169.

- Sallent, O., Palau, R., & Guia, J. (2011). Exploring the legacy of sport events on sport tourism networks. European Sport Management Quarterly, 11(4), 397–421.

- Shilbury, D., Westerbeek, H., Quick, S., Funk, D., & Karg, D. C. A. (2014). Strategic sport marketing (4th ed.). New South Wales: Allen & Unwin Academic.

- Slack, T. (2003). Sport in the global society: Shaping the domain of sport studies. International Journal of the History of Sport, 20(4), 118–129.

- Smith, A. (2014). Leveraging sport mega-events: New model or convenient justification? Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 6(1), 15–30.

- Smith, A. C. T., & Stewart, B. (2010). The special features of sport: A critical revisit. Sport Management Review, 13(10), 1–13.

- Solleiro, J. L., & Castañón, R. (2005). Competitiveness and innovation systems: The challenges for Mexico’s insertion in the global context. Technovation, 25(9), 1059–1070.

- Stewart, B., & Smith, A. (1999). The special features of sport. Annals of Leisure Research, 2(1), 87–99.

- Szymanski, S. (2009). Playbooks and checkbooks: An introduction to the economics of modern sports. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tichaawa, T. M., & Swart, K. (2010). South Africa’s image amongst African fans and factors that will influence their participation in the 2010 FIFA World Cup: The case of Cameroon. UNWTO/South Africa International Summit on Tourism, Sport and Mega-events, 24.

- Weed, M. (2006). Sports tourism research 2000–2004: A systematic review of knowledge and a meta-evaluation of methods. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11(1), 5–30.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553.

- WTTC. (2017). Travel and tourism economic impact 2017 United Arab Emirates. Retrieved from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/benchmark-reports/country-reports-2017/uae.pdf

- Zanakis, S. H., & Becerra-Fernandez, I. (2005). Competitiveness of nations: A knowledge discovery examination. European Journal of Operational Research, 166(1), 185–211.

- Zehrer, A., Smeral, E., & Hallmann, K. (2017). Destination competitiveness—A comparison of subjective and objective indicators for winter sports areas. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 55–66.