ABSTRACT

This study provides a comprehensive review of the knowledge-hiding field based on objective measures of impact. Research on knowledge hiding has grown in recent years, resulting in a body of literature that now includes 103 articles specifically discussing knowledge hiding and/or knowledge withholding in organisations. Our study presents a quantitative review of these studies using a combination of three bibliometric techniques: document co-citation analysis, co-word analysis and bibliographic coupling. We present an overview of the past, present, and proposed future of knowledge-hiding research. Our bibliometric review enables us to identify the most influential topics, determine the underlying structure and theoretical foundations of the field, and detect emerging topics. The theoretical and methodological implications of our work suggest the emergence of new sub-fields and future opportunities for connections with other streams of knowledge-management research.

1. Introduction

Knowledge hiding (hereafter: KH) is seen as counterproductive knowledge behaviour by employees that hinders firm creativity, productivity, and competitiveness (Černe et al., Citation2017; Serenko & Bontis, Citation2016). Indeed, business growth usually occurs when knowledge-based companies combine information, data, and knowledge (Davis & Botkin, Citation1994), rather than hide it. Therefore, over the past decade, scholars in the knowledge-management (hereafter: KM) field have started to explore KH as an important antecedent of effective internal collaboration, employee productivity, and firm growth in organisations.

In their pioneering work, Connelly et al. (Citation2012) introduced the KH concept and proposed a widely accepted definition that “knowledge hiding is an intentional attempt by an individual to withhold or conceal knowledge that has been requested by another person” (Connelly et al., Citation2012, p. 65). The authors also developed a measure for KH. However, even prior to this conceptualisation, research had covered behaviours that could be characterised as KH, captured by terms such as hidden knowledge (Riley, Citation1985) or hoarding (keeping) knowledge (Al‐Alawi et al., Citation2007). In fact, the notion that organisational members deliberately withhold knowledge had already drawn the attention of sociologists and anthropologists studying organisations over 50 years ago (Mechanic, Citation1962).

To date, KH research has dealt with the various antecedents and consequences of KH. However, this research is currently scattered across many constructs, which makes it difficult for researchers to gain an overview of this field. While there have been some recent reviews of the KH concept (Connelly et al., Citation2019; Ruparel & Choubisa, Citation2020; Serenko, Citation2019), these have been narrow in their scope or time frame, or have applied qualitative/narrative review methodologies. Although these previous research studies performed important exploratory work in mapping (some aspects of) the KH field, we are still lacking a systematic, comprehensive, and objective overview of the KH field – one that can only be obtained through quantitative analysis. Such an approach would provide a comprehensive and integrative “big picture”, objectively demonstrating and explaining where the research in the field began, which articles are currently the most significant, what directions the field is going in, and what areas remain unexplored. To address this gap, we used a quantitative bibliometric methodology to create a comprehensive view of the field based on objective measures of impact (Zupic & Čater, Citation2014). Bibliometric techniques enabled us to examine the articles that established the KH field, assess how narrow or diverse the KH field is, and identify the main streams of research for the future. In effect, lessons from the past and present can guide future research on KH.

In our research, we contribute to the overall KH field by presenting a quantitative and descriptive overview of all KH research to date by combining multiple bibliometric analytic techniques. The use of these methods minimises subjectivity and thus increases the strength of the reliability of our findings. First, we apply co-citation analysis and integrate all citations related to the topic in the SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index) Web of Knowledge (Osareh, Citation1996; White & Griffith, Citation1981). Our aim was to advance the field by investigating how past research has helped to create the KH field. The data uncover the intellectual structure of the field and its development during the 1985–2021 timeframe. Furthermore, the data pinpoint the most important clusters and connections between works. By uncovering these connections, we facilitate a better understanding of the KH field’s origins and development. Second, we contribute to the field of KH by presenting a semantic (content) overview of the topics and key themes investigated in the KH field, using co-word analysis (Acedo et al., Citation2006). Our third potential contribution involves exploring the future development of this fast-growing field through bibliometric coupling. By applying this technique, we reveal the topics and authors that are currently contributing the most to the field, which enables us to make informed suggestions for the future of the KH field (Zupic & Čater, Citation2014). Finally, we propose antecedents and consequences to be explored in the KH field alongside the dyads at specific levels of research in order to augment the understanding of what KH and its nomological net is and how research can be further developed. Taken together, this article informs researchers about where the field began, what theories have been applied, which streams of research have emerged, how clusters have developed over time, and what specific topics are connected to KH. These discussions elicit new streams and suggestions to further develop the KH field.

2. Theoretical background

KM started to take shape in the 1980s when companies began to pay attention to the importance of knowledge in business (Zeleny, Citation1987). About a decade later, the first articles and conferences on the topic emerged (Davis & Botkin, Citation1994; Edwards et al., Citation2009; Hansen, Citation1999). One of the KM processes first investigated was knowledge sharing. Scholars have shown that knowledge sharing is a vital process in companies, as it can advance corporate culture (Ford & Staples, Citation2010) and create intangible rewards (Connelly & Kelloway, Citation2003). At the same time, negative behaviours such as knowledge hoarding (Webster et al., Citation2008) and knowledge withholding have gained attention (Anaza & Nowlin, Citation2017; Kang, Citation2017; Lin & Huang, Citation2010).

In this stream of research, Connelly et al. (Citation2012) described KH as “an intentional attempt by an individual to withhold or conceal knowledge that has been requested by another person” (Connelly et al., Citation2012, p. 65). An example of KH is when someone asks a co-worker for a report and the co-worker does not provide it or provides only part of it. Connelly et al. (Citation2012) identified three main dimensions of KH: (a) rationalised hiding (when the person who hides the knowledge claims that he or she is not capable of providing it or blames a third person), (b) playing dumb (when the hider pretends not to know), and (c) evasive hiding (when the person gives incorrect information or promises to answer in the future without any intention of doing so). Kumar Das and Chakraborty (Citation2018) later expanded this to four hiding strategies: playing innocent, being misleader/evasive hiding, rationalised hiding, and counter-questioning.

It is important to note that there are substantial differences between knowledge sharing and KH. In the context of large organisations, Connelly et al. (Citation2012) stressed that a lack of knowledge sharing can mean a lack of existing knowledge, whereas KH refers to the intentional concealment of knowledge. Scholars have identified a number of key factors that foster KH: distrust (Connelly et al., Citation2012; Kumar Das & Chakraborty, Citation2018), lack of recognition and reciprocation (Kumar Das & Chakraborty, Citation2018), and interpersonal conflict (Losada-Otálora et al., Citation2020). Research to date has culminated in Connelly et al. (Citation2019)’s overview of the field and beyond (Ruparel & Choubisa, Citation2020), with particular suggestions for where the field should go in the future. Our current article complements their results by presenting new directions for KM and highlighting the concepts in need of further exploration.

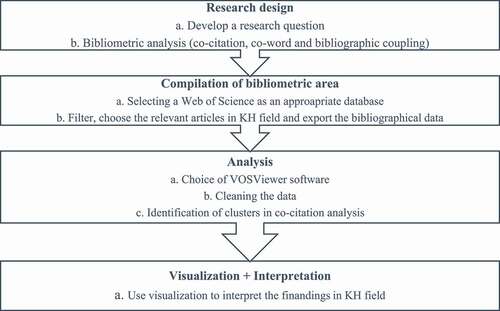

3. Methodology

For our quantitative study, we used three methods of bibliometric analysis (co-citation, co-word, and bibliographic coupling). Bibliometric analysis has been used in various disciplines to investigate different areas and topics, such as KM (Gaviria-Marin et al., Citation2019), social entrepreneurship (Rey-Martí et al., Citation2016), entrepreneurial orientation (Martens et al., Citation2016), innovation (Randhawa et al., Citation2016), and family businesses (Benavides-Velasco et al., Citation2011; Casillas & Acedo, Citation2007). Over the past several years, the research pool for KH has expanded to become a multidisciplinary field combining entrepreneurship, management, business, and psychology (Babič et al., Citation2018; Černe et al., Citation2014).

Before the widespread use of bibliometric analysis, scholars traditionally used various methods of literature review, including both qualitative and quantitative methods, such as meta-analyses, interviews, and observations (Creswell, Citation2009). In recent years, scholars have introduced a new approach to synthesising research findings called “science mapping” (Cobo et al., Citation2011). This approach “uses bibliometric methods to examine how disciplines, fields, specialties, and individual papers are related to one another” (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015, p. 429).

These bibliometric methods are not new and make use of widespread, easily accessible databases. Such methods are especially useful at the beginning of a research project to assess who the most influential researchers are in a given field (Waltman et al., Citation2010; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). The application of bibliometric analysis is growing, giving management scholars a valuable tool to overcome subjective analysis in literature reviews. There are two main uses of bibliometric methods: science mapping and performance analysis. Scholars can use these two options to visualise and evaluate the structure and dynamic features of specific research (Morris & Van Der Veer Martens, Citation2008). Based on the different uses of data, we can identify five bibliometric methods: bibliographic coupling, citation analysis, co-citation analysis, co-word analysis, and co-author analysis (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). There are advantages and disadvantages to each method. Some of the advantages include being able to quickly and easily determine the most influential work in specific fields. However, the disadvantages include the time needed for an article to gather citations. As a result, some relevant works may not be connected, even though they might become connected in the future (Waltman et al., Citation2010; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Bibliographic coupling is a viable method to overcome these disadvantages, as this approach puts additional weight on more recent studies when reviewing published articles. Consequently, the analysis can reliably be performed, even if the field is rather young.

We applied bibliometric analysis to the KH literature in order to create an overview of the field, determine the relationships among the concepts, identify the main authors, and investigate the intellectual structure of the field. Using science mapping and performance analysis helps to reduce subjectivity and bias and improves understanding of the current and future structure of the KH field.

3.1. Bibliometric co-citation analysis

Our research began with a bibliometric co-citation analysis to conduct a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the KH field. Co-citation analysis uses citation tools to connect journals, authors, and various documents (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015) in order to ascertain the beginnings of the field and its whole structure. The analysis is built on cited articles from the past to see where a specific field originated (Small, Citation1973).

We used co-citation analysis to answer the following research question: Who are the central, peripheral, and bridging researchers in the field, and how has the structure developed over time?

3.2. Data and procedure

To conduct co-citation analysis, we used the procedure specified by Zupic and Čater (Citation2015). We used the SSCI Web of Knowledge’s Social Science Citation Index (WOS) as the bibliometric database, as it represents the most reliable and comprehensive data source (Jacso, Citation2005; van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010). The majority of bibliometric studies have used this database (Černe et al., Citation2016; Lopez-Fernandez et al., Citation2016; Schildt et al., Citation2006).

We applied all citation databases provided by WOS using the search approach “OR” (Černe et al., Citation2016; White & Mccain, Citation1998). Search terms stemmed from the most cited article in the KH field (i.e., Connelly et al.’s (Citation2012) article) and the definition of KH, which also includes knowledge withholding. We used the terms knowledge hiding, hiding knowledge, knowledge withholding, and withholding knowledge. To ensure that the knowledge base was valid, we limited our search to journal articles in the English language published from 1900 to 2021. We refined the categories of the search terms to include “management”, “business”, “economics”, and “psychology multidisciplinary”. The focus was on articles and editorial material because peer-reviewed articles ensure the quality of research.

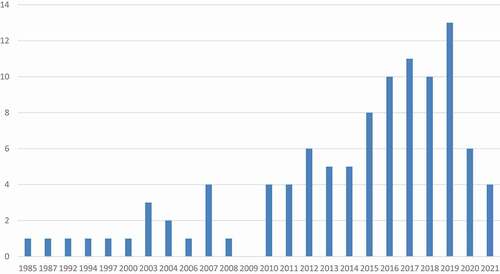

The first search returned 472 articles. We reviewed the abstracts and eliminated articles that were not relevant to the search. We ended up with 103 articles (primary articles) published from 1985 to 2021. The sum of times cited was 3,818; without self-citations, it was 3,470, while the average citations per item was 37.07 and the h-index was 33. We retrieved 2,584 cited articles, and 2,533 without self-citations. As shown in , the KH field has grown considerably in recent years, with the number of articles on KH almost doubling between 2012 and 2017; nevertheless, the field is still in its development phase (Anand, Centobelli & Cerchione, Citation2020; Y. Wang et al., Citation2019).

After exporting the SSCI Web of Knowledge data, we used VOSviewer (bibliometric software) to visualise and analyse the KH bibliometric network (Ferreira, 2018). Through VOSviewer, we analysed the dataset using co-citation analysis with cited references, with documents as the unit of analysis. We had a smaller number of articles because of the specificity and newness of the research field, so we omitted documents cited three or fewer times from the database – a lower threshold than the average citation value. Of the 5,369 cited references (secondary articles), 281 met the threshold. We divided the period between 1985 and 2021 into three intervals. Černe et al. (Citation2016) noted that “co-citation analysis builds on secondary, cited articles and is less sensitive to starting year”. Based on this idea and considering the annual increase in articles, we divided our time period into three segments. The first interval was the longest at 24 years (1985–2009), the second interval was 4 years (2010–2014), and the third interval was 7 years (2015–2021). The time span was shorter for the second and third intervals given the large growth in the number of publications. Of the 103 articles, 17 (17%) were published from 1985 to 2009, whereas 24 (23%) were produced from 2010 to 2014, and 62 (60%) were produced from 2015 to 2021. shows the top 17 articles with the highest link strengths, citations, and number of links in the KH field.

Table 1. Top 17 with the highest link strength, citations, and number of links in the knowledge-hiding field

4. Co-citation analysis results

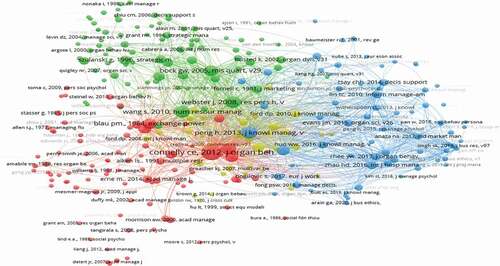

Of the 103 selected articles, Connelly et al. (Citation2012) was the most cited article (44 citations). As shown in , the oldest article cited in KH research (i.e., secondary article) was Blau (Citation1964), with 20 citations. Since KH deals with hiding knowledge or information, the concept of KH involves an ongoing relationship between two or more people. Accordingly, many articles in the KH field have used social exchange theory to explain the interaction between people in dyadic relationships (Blau, Citation1964). Furthermore, these citations show that the field is still new but has undergone significant growth. presents the flow diagram of the co-citation process analysis and shows the visualisation network of the KH field based on our co-citation analysis.

Figure 2. Visualisation network of the knowledge-hiding field; co-citation analysis.

The starting year of publications (primary articles) in the first interval was 1985. The first articles were published in the Journal of Political Economy by Riley (Citation1985) and in the Journal of Public Economics by Crocker and Snow (Citation1992), who mentioned the hidden knowledge of sellers (agents). Up until Connelly et al. (Citation2012)’s conceptualisation of KH, articles employed the terms “hidden knowledge” (Crocker & Snow, Citation1992; Riley, Citation1985), “withholding inputs or knowledge” (Lin & Huang, Citation2010; Price et al., Citation2006), or “knowledge sharing barriers” (Lilleoere & Hansen, Citation2010).

4.1. Co-citation cluster analysis

Co-citation analysis of the 103 most relevant articles (visualised in ) from 1985 to 2021 revealed four clusters (an overview of clusters is presented in ). The first cluster (represented in red in ) consisted of 88 articles. Based on citations, links, and link strength, the most significant articles in Cluster 1 were Bartol and Srivastava (Citation2002), Černe et al. (Citation2014), Connelly and Kelloway (Citation2003), and Connelly et al. (Citation2012), Connelly (Citation2015), Cropanzano and Mitchell (Citation2016), Gouldner (Citation1960), and Blau (Citation1964). We labelled Cluster 1 “Social exchange and knowledge hiding”. Here, we observed a more individual–dyadic research approach with a combination of psychology, sociology, and management. Many authors explained the specific dyadic relationships in KH through social exchange (Blau, Citation1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2016; Gouldner, Citation1960). The formation of the KH literature began with the acknowledgement of knowledge sharing and ways for companies to increase knowledge sharing through incentives, rewards (Bartol & Srivastava, Citation2002), and trust.

Table 2. Summary of knowledge hiding co-citation network (Clusters 1–4)

Connelly and Kelloway (Citation2003) developed a measure to evaluate employees’ perception of a knowledge-sharing culture, finding that how employees perceive management’s support and the existence of positive social interactions are significant predictors of knowledge-sharing culture. The authors identified gender differences, namely that female participants need a more active social interaction culture before they perceive culture to have knowledge-sharing characteristics (Connelly & Kelloway, Citation2003). Connelly et al. (Citation2012) introduced the new construct of KH after realising that, even if organisations facilitate knowledge transfer, employees may still be reluctant to share knowledge. They identified three factors of KH; for all these factors, distrust was a predictor of KH (Connelly et al., Citation2012). Černe et al. (Citation2014) went a step further to explain the consequences of KH for individuals and organisations. When a person hides knowledge, fewer ideas are generated, which in turn affects employees’ creativity and creates a “reciprocal distrust loop” (Černe et al., Citation2014). Connelly and Zweig (Citation2015) investigated the negative consequences of KH and how employees were expected to disrupt relationships through KH behaviour. They found that different types of KH could boost or stop the KH cycle (Connelly & Zweig, Citation2015).

Turning our attention to Cluster 2 (the green cluster in ), this cluster consisted of 82 articles that predominantly used an individual approach to knowledge sharing; accordingly, we labelled Cluster 2 “Individual knowledge creation and transfer”. These articles also investigated the reasons as to why some approaches to knowledge sharing fail. The most cited article in Cluster 2 was by Webster et al. (Citation2008), who showed that organisational attempts to encourage employees to share knowledge and ideas usually fail, despite various initiatives to support knowledge sharing, such as implementing technology to stimulate exchange (Cabrera & Cabrera, Citation2002). Individuals may still hold on to their knowledge through social exchange, secrecy, and territorial behaviour. In a review of studies related to individual-level knowledge sharing, S. Wang and Noe (Citation2010) identified four important research areas concerning knowledge sharing: “organizational context, interpersonal and characteristic of a team, cultural and individual characteristics and motivational factors” (S. Wang & Noe, Citation2010). Building on the reasons for someone to share (or not) knowledge, (Bock et al., Citation2005) confirmed that attitudes, subjective norms, and organisational climate influence a person’s intention to share. However, extrinsic rewards can have a negative impact on the sharing perspective (Bock et al., Citation2005). Grant (Citation1996) and Nonaka (Citation1991) explored knowledge from the organisational perspective, proposing that instead of accepting that knowledge resides within the individual, organisations need to be knowledge applicators, not just knowledge creators (Nonaka, 1995; Grant, Citation1996).

In Cluster 3, articles mostly dealt with antecedents of KH in organisations, such as territoriality (i.e., “an individual’s behavioral expression of his or her feeling of ownership toward a physical or social object” (Brown, Citation2005) and the consequences of KH, such as decrease in creativity (Černe et al., Citation2014) and performance (Fong et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, we labelled this cluster “Antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding”. One of the motivating factors for KH is an intense sense of psychological ownership (i.e., “the feeling of possessiveness and of being psychologically tied to an object” (Pierce et al., Citation2001). Peng (Citation2013) found that territoriality was a strong mediator between knowledge-related psychological ownership and KH, and that high levels of psychological ownership were positively associated with KH. Huo et al. (Citation2016) obtained similar results at the team level. Serenko and Bontis (Citation2016) explored the antecedents and consequences of KH in organisational settings. They found that job insecurity stimulated KH behaviour and employees’ negative responses to KH. (Rhee & Choi, Citation2017) investigated knowledge sharing, hiding, and manipulation and how individuals deal with their social status in a working group. Overall, this stream of research shows that research must also consider the attitudes and values of individuals in the knowledge-sharing process when recommending what organisations should do to improve knowledge sharing.

In Cluster 4 (36 articles), the articles mostly dealt with the knowledge holder’s sense of ownership and theories related to psychology, sociology, and communication studies. We called this cluster “Social and communication aspects of knowledge sharing and hiding”. Brown et al. (Citation2005) provided a conceptual overview of territoriality in organisations, explaining how to restore or communicate territories and the effects of territoriality on different organisational factors, such as conflict or commitment. Researchers also used the concept of psychological ownership to explain “why” and “how” under certain circumstances employees or individuals could start to feel ownership towards the company (Pierce et al., Citation2001). Ford and Staples (Citation2010) elucidated the difference between full and partial knowledge sharing, and, in line with previous research, showed that distrust and psychological ownership can cause partial knowledge sharing (Ford & Staples, Citation2010).

5. Co-word analysis

The second analysis we conducted was a co-word analysis in which the unit of analysis was a word. Co-word analysis is a bibliometric technique that searches for connections between concepts that co-occur in titles, abstracts, or keywords. The advantage of this technique is that the co-word can produce a field and structure. However, the disadvantage is that words can appear in different forms and meanings (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). The main idea behind co-word analysis is that words appearing often in documents might indicate related concepts. Among the bibliometric methods, co-word analysis is the only method that uses real content to produce similarity measures (He, Citation1999; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015).

Co-word analysis searches keywords, titles, and full text to create a semantic map of the field, as well as to show the key constructs the field is built on, both in the past and in current research (He, Citation1999). He (Citation1999) stated that co-word analysis has become a “powerful tool for knowledge discovery in databases” (He, Citation1999). The central publication on co-word analysis is Callon et al. (Citation1986), in which the authors emphasised the power of words and laid out the theoretical foundation of co-word analysis. Following Callon et al.’s (Citation1986) publication, co-word analysis spread to other European countries and the United States.

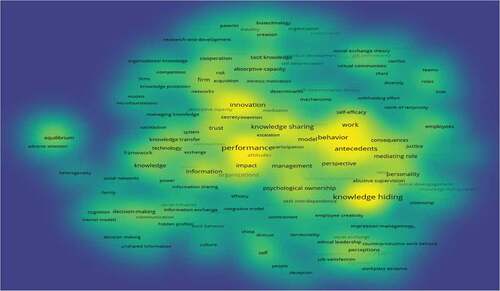

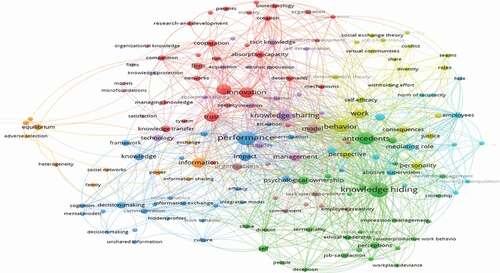

For the co-word analysis, we used the same database as for the co-citation analysis. Of the 686 keywords, only 160 met our requirement of appearing at least twice. The analysis produced nine clusters. The strongest words in terms of number of links and total link strength were “knowledge hiding”, “performance”, and “antecedents”. In all nine clusters (), there was a total of 1,842 links and a link strength of 2,423.

Figure 4. Co-occurrences of keyword network (min 2).

In Cluster 1, the three most dominant concepts were knowledge management, innovation, and trust. Cluster 2 dealt with knowledge hiding, antecedents, and psychological ownership. Cluster 3 focused on performance and impact, which emerged as highly visible keywords; interestingly, however, very few articles explored performance directly.

The prevailing concepts in Cluster 4 were behaviour and work, predominantly from the psychological literature. In Cluster 5, knowledge sharing was the most important concept. Cluster 6 showed the importance and mediating role of knowledge withholding. Cluster 7 was about the importance of information, Cluster 8 was about model, and Cluster 9 was about management. Overall, the nine clusters of keywords and concepts revealed the past, present, and future of the KH literature.

Narrowing in on the specific topics identified by the co-word analysis, besides the KH concept, psychological concepts such as personality, perception, and territoriality emerged, along with concepts of knowledge sharing, KM, work, and antecedents. These concepts have already been explored in connection with the KH field. However, two big circles were found for performance and innovation, which led us to conclude that performance and innovation are important and measurable factors in the KH field, usually deemed to be the most common consequences of KH. That being said, it is worth mentioning that the words performance and innovation have only appeared in two article titles in the last five years, neither of which was directly associated with KH and performance.

Additional concepts were equilibrium, asymmetric information, and signalling games. There were also words such as biotechnology, creation, and patents, indicating that research on KH is becoming interdisciplinary. We note that, in , the overall total link strength and most important occurrences are for the concepts of KH, performance, antecedents, behaviour, and knowledge sharing.

6. Bibliographic coupling

In the final stage, we used bibliographic coupling to explore the KH field. Bibliographic coupling shows the extent to which two articles reference the same articles. Even though bibliographic coupling has been criticised for speculating on future research based on current trends (hot topics), it is nevertheless a useful tool for positioning current contributions to the field (Ferreira, 2018). Following Zupic and Čater (Citation2015), we decided that it would be best to perform the bibliographic coupling using a restricted timeframe of the last seven years. As mentioned, we found 103 relevant articles about KH, 62 of which were published in the last seven years (2015–2021).

6.1. Articles

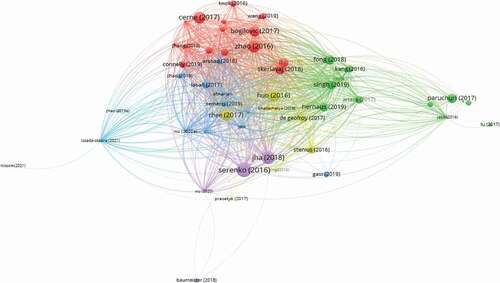

The largest set of connected items consisted of 54 primary articles, which we then analysed in order to better understand the foundations of the KH field. The total number of links in all six clusters was 888, with a total link strength of 4,326. Based on the links, we observed that this young field is still expanding and growing, showing significant improvement. Topics of interest in our bibliographic coupling analysis were knowledge hoarding, information sharing, individual and group performance, knowledge networks, job design, personality, and rewards.

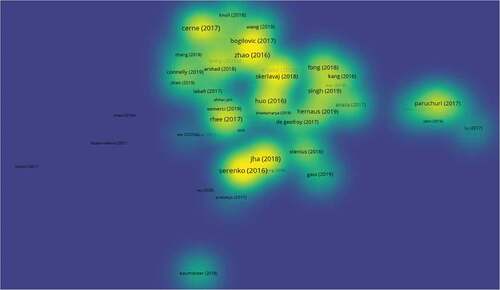

Over the last five years, the KH field has been somewhat fragmented, as shown clearly in . The circles in represent important articles/topics and researchers in this field. One can see that there is no predominant, large circle, but rather several smaller ones. presents a cluster density visualisation.

Figure 6. Bibliographic coupling network of the field by documents.

Figure 7. Cluster density visualisation of bibliographic coupling.

The analysis yielded six clusters shown in red, green, blue, yellow, purple, and light blue in . In the first cluster (in red in ), “The work context of knowledge hiding”, the most important article was the one by Černe et al. (Citation2017), which focused on the interplay among team mastery climate, KH, and job characteristics. Bogilović et al. (Citation2017) focused on cultural intelligence, KH, individual and team creativity, as do other articles close to these two circles. Both articles discussed KH in organisational settings and investigated innovative or creative work behaviour (Bogilović et al., Citation2017; Černe et al., Citation2017). Škerlavaj et al. (Citation2018) and Babič et al. (Citation2018) had the highest total link strength in researching the effects of time pressure, perspective taking, and prosocial motivation on KH and the negative consequences of KH in project teams.

In the second cluster (in green), labelled “Performance and team dynamics in knowledge networks”, Paruchuri and Awate (Citation2017) and Fong et al. (Citation2018) produced the highest cited articles. These articles focused on organisational knowledge networks (Paruchuri & Awate, Citation2017) and team creativity, where absorptive capacity (i.e., “dynamic organizational capability to value, assimilate, and apply new knowledge” (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990) fully mediates the relationship between KH and team creativity (Fong et al., Citation2018). Interestingly, the article with the highest total link strength was Singh (Citation2019), who investigated territoriality with respect to task performance and workplace deviance, and how territoriality relates to KH.

The third cluster (in blue), “Knowledge hiding as an obstacle of innovation”, had Labafi (Citation2017) as the most cited article. This article explored the reasons for individuals to hide organisational knowledge from their colleagues in the software industry, for example, power, complexity of knowledge, and internal competition, among others.

In the fourth cluster (in yellow), labelled as “ Knowledge hiding behavior”, the highest cited article was one entitled “Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: a multilevel study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behaviour”. Dedahanov and Rhee (Citation2015) examined the relationship between trust, science, and organisational commitment. Bhattacharya and Sharma (Citation2019) explored whether knowledge-based psychological ownership or corporate-based psychological ownership and territoriality predicted KH in different industries in India.

The fifth (in purple, labelled “Triggering factors of KH”) and sixth (in light blue, labelled “Interpersonal conflict in KH”) clusters were the smallest, but still contained significant numbers of citations. The dominant articles in the fifth cluster were articles by (Jha & Varkkey, Citation2018; Serenko & Bontis, Citation2016), both of which investigated KH in the workplace environment. In cluster six, Losada-Otálora et al. (Citation2020)’s article on interpersonal conflict, well-being and KH had the highest link strength.

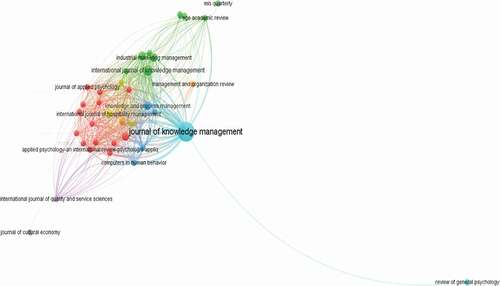

6.2. Journals

We then analysed which journals had published KH articles in the last six years. In this analysis, we considered a threshold of one source article. The largest set of connected items consisted of 37 items. Bibliographic coupling analysis by source in the period 2016–2021 showed that the most relevant journal (i.e., the one with the highest number of links and total link strength) was the Journal of Knowledge Management. A detailed list is shown in . presents a visualisation of the network, showing a stronger circle around the Journal of Knowledge Management. Other journals are represented by smaller circles, indicating that KH research has penetrated other fields to a lesser degree.

Table 3. Bibliographic coupling by source

6.3. Authors

In terms of the authors in the KH field, we found 128 connected authors in the 54 articles in the period 2016–2021. shows the list of authors with the highest number of articles, citations, and total link strength. Sixteen of the 128 authors have published more than one article, and the first two on the list have the highest total link strength. Key geographical areas covering KH were Slovenia, Norway, Croatia, Canada, and China, with India as an emerging area.

Table 4. Number/citations/total link strength per author

7. Discussion and contributions

The literature has pointed out that knowledge, know-how, or KM, in general, is one of the most valuable assets for a company to achieve competitive advantage, greater innovation, and better performance (Desouza & Awazu, Citation2006). For many years, research has shown the value of knowledge sharing for companies in terms of individual and group performance, among other outcomes (Dupuy, Citation2004). However, scholars have noticed some barriers to knowledge-sharing research, such as lack of communication skills, difference in national culture, lack of time and trust, and its various trajectories, whereas others have seen an opportunity to explore these new concepts (Lilleoere & Hansen, Citation2010; Riege, Citation2005).

Through our bibliometric and co-citation analysis, we discovered that the concept of KH has mostly been derived from the knowledge-sharing literature and research on social psychology–reciprocity, social exchange, and dyads. In their special issue on KH in organisations, Connelly et al. (Citation2019) presented five novel articles (Gagné et al., Citation2019; Jiang et al., Citation2019; Offergelt et al., Citation2019; D. Zhao & Strotmann, Citation2014; H. Zhao et al., Citation2019) showing the importance of KH in organisations, its antecedents, and outcomes. All five articles used theories drawn from psychology to explain different types of human behaviour in different settings (individual, dyadic, or organisational). Despite these important contributions to this area of research, there is still a lack of cross-level studies, multi-level studies, and investigations to examine the specific manifestations and driving forces of KH at the individual, dyadic, and organisational levels.

Compared to recent overviews of the KH field (Hernaus et al., Citation2019; Ruparel & Choubisa, Citation2020; Serenko, Citation2019), our bibliometric analysis identified some similar lines of inquiry and challenges to the KH literature, along with additional insights. Psychology theories were prevalent in our analysis, with most scholars drawing on those theories to explain why and under what circumstances KH occurs. Both Connelly et al. (Citation2012) and Wang and Noe (Citation2010) drew the connection between knowledge sharing and KH. One challenging aspect of research on KH is that it involves individual decisions, as well as decisions and factors at the organisational level (Anand et al., Citation2020; Connelly et al., Citation2019). While our bibliometric analysis delineated the “big picture” of the KH field, a special issue of the Journal of Organizational Behaviour directed us towards specific and novel directions for understanding KH, such as exploring the role of leader and leadership, interpersonal justice and power differentials (Connelly et al., Citation2019).

Our content analysis (co-word) of KH also yielded interesting findings. One such finding was that, even though performance and innovation emerged as important keywords, only a few articles were directly linked to the study of performance and innovation in the context of KH. In addition, we found that there was no specific geographical area dominating the clusters, suggesting less “elitism” and less Western-school direction in the KH field, as opposed to more established fields. This is possibly because the field is still in its development phase.

The bibliographic coupling method elucidated KH in the context of business and management, e.g., related to performance, team dynamics, and the negative outcomes of KH. The analysis also highlighted the psychological aspects of KH, such as territoriality and psychological ownership. Some clusters in this coupling covered vastly different fields and theoretical frameworks, referencing diverse literature ranging from psychology to sociology, strategic management, and industrial economics. Despite this breadth, our analysis identified KH research topics in need of further development. These include a more specific and nuanced assessment of how KH affects work performance, and under which contextual conditions at different levels. Furthermore, team dynamics with regards to not only interpersonal relationships, but team composition, structure, and team-members’ networks of various nature developing over time are in dire need of further investigation, potentially applying social network perspectives. Additionally, an empirical assessment of potential similarities and differences of KH with similar or related constructs, such as employee silence and knowledge withholding, could provide and interesting evidence-based clarification of the constructs and its discriminant validity. Our bibliographic coupling analysis pointed out that knowledge withholding appeared to be a separate concept from KH, as demonstrated by the disconnection of the two clusters. Connelly et al. (Citation2012) and Webster et al. (Citation2008) have investigated how knowledge hoarding and KH are two distinct concepts of knowledge withholding, each with different antecedents and consequences for an organisation. However, Webster et al. (Citation2008) and Anand et al. (Citation2020) pointed out that little empirical research has been conducted on this distinction. Consequently, further research is needed on the concepts of knowledge hoarding and KH and how they relate, before we can confidently conclude that they do indeed differ and are part of the broader concept of knowledge withholding.

8. Limitations, future directions, and conclusion

This was the first effort to systematically map the KH field. However, our bibliometric analysis has some limitations to consider. For example, we only used one database (SSCI Web of Knowledge) and evaluated impact based on citations covered by SSCI. This process was therefore limited by impact factors and did not cover all scientific journals (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Since KH is a relatively new field, it will take time for articles to be recognised and cited. In terms of the homogeneity of the sample, we included peer-reviewed articles, books, and relevant articles. In the future, it would be valuable to include other publications such as conference proceedings and reports. Considering it is a new and emerging field, we set a minimum threshold level, and clusters were formed based on that threshold; this represents a limitation of this bibliometric analysis as some potentially interesting articles might have been excluded.

Based on our analyses, we identified several future directions for the KH field. First, the clusters in the co-citation analysis presented an overview of the core theoretical backgrounds, ranging from psychology to strategic management and information technology. Notably, there was no connection with entrepreneurship, although concepts related to entrepreneurship, such as innovation and creativity, appeared in the majority of the clusters in the content analysis. In light of this, an interesting research question would be to investigate whether knowledge hiding differs among entrepreneurs, startups, venture capitalist, or other entities in the entrepreneurship field. Furthermore, we found evidence that knowledge sharing is important for entrepreneurs, SMEs, and family firms (Chirico, Citation2007; Coulson-Thomas, Citation2004; Cunningham et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). Therefore, it would be valuable to further explore any barriers to knowledge sharing and the motivations for KH in these entrepreneurial settings. Building knowledge in this area would advance the theoretical perspective of KH in entrepreneurship context.

Second, in terms of organisation-level research, it would be interesting to see whether KH is more prevalent in top-down relationships (Butt, Citation2019) than in bottom-up or peer-to-peer relationships (Arain et al., Citation2020). If so, there could be a difference between levels of management (low, middle, or top management) in terms of KH. Research at the organisational level considers the entire organisation, which is reflected through organisational culture, a known enabler of knowledge sharing (Bollinger & Smith, Citation2001; Chirico, Citation2007). Yet, organisational culture could also provoke KH. Therefore, investigating which management levels should pay closer attention to KH could be advantageous for the KM field. Moreover, it could be beneficial to explore cross-level effects, the variables at different levels, and how managers interact with one another (Fisher & Aguinis, Citation2017).

Third, despite the importance of performance that emerged in our analysis, it was interesting to see how few articles pointed to performance as a measure for KH (Evans et al., Citation2015; Singh, Citation2019). Because of the lack of literature on this topic, we suggest that researchers should directly examine KH and performance at the individual, team, and organisational levels using different dimensions and different facets of performance (in-role, extra-role; financial, non-financial, etc.). Further investigation is needed to determine whether and how employees use KH to increase their performance (Evans et al., Citation2015). In addition, an interesting question is how companies measure success beyond performance and how that might be related to KH.

Fourth, as psychology was the most present theoretical background in our bibliometric analysis, our findings yielded suggestions for lines of inquiry related to psychology concepts and KH (Fisher & Aguinis, Citation2017). Scholars in some articles have used personality traits (optimistic and pessimistic) to identify and explain KH (Anand, Citation2014; Demirkasimoglu, Citation2015). Therefore, we propose that future research should investigate whether and under what conditions KH can be considered a positive or negative behaviour, with positive or negative intentions and consequences.

Next, the concept of emotional intelligence is becoming an interesting topic for exploration. For example, de Geofroy and Evans (Citation2017) tried to answer the question “are emotionally intelligent employees less likely to hide their knowledge?”, but suggested that this question needed further investigation. In the workplace cluster in our co-word analysis, the concept of workplace deviance was important. Singh (Citation2019) discovered that KH had a positive impact on workplace deviance and suggested that researchers explore this concept further in the future. In organisational settings, it would be interesting to explore different employees’ backgrounds and whether their competencies influence KH. It would also be fruitful to discover whether perceptions of work–life balance influence a person’s KH practices and what other personal or organisational settings foster KH.

One final future direction is related to ethical issues. Although Khalid et al. (Citation2018) explored Islamic work ethic, ethical issues should be more present in the KH literature given that KH can introduce some negative ethical dynamics into the workplace. Organizations need to oversee and control ethical values/issues in the workplace, including those related to KH.

To conclude, the KH field has grown considerably, but interdisciplinary research is needed to more fully investigate the various concepts. Crucially, the KH field needs a greater structure and focus to direct future research in this area.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The analysis was done in March 2021. Articles at the beginning of March 2021 are included in this figure.

2. Total link strength shows the number of publications in which two keywords occur together.

References

- Acedo, F. J., Barroso, C., Casanueva, C., & Galán, J. L. (2006). Co‐authorship in management and organizational studies: An empirical and network analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 43(5), 957–983. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00625.x

- Al‐Alawi, A. I., Al‐Marzooqi, N. Y., & Mohammed, Y. F. (2007). Organizational culture and knowledge sharing: Critical success factors. Journal of Knowledge Management 11(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270710738898

- Anand, A., Centobelli, P., & Cerchione, R. (2020). Why should i share knowledge with others? A review-based framework on events leading to knowledge hiding. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 33(2), 379–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.25.355

- Anand, P., K. K. J. (2014) ‘Big five personality types & knowledge hiding behaviour : A Theoretical framework’, Archives of Business Research, 2(5), pp. 47–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.25.355

- Anaza, N. A., & Nowlin, E. L. (2017). What’s mine is mine: A study of salesperson knowledge withholding & hoarding behavior. Industrial Marketing Management, 64, 14–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.03.007

- Arain, G., Bhatti, Z. A., Ashraf, N. & Fang, Y.-H. (2020) ‘Top-Down Knowledge Hiding in Organizations: An Empirical Study of the Consequences of Supervisor Knowledge Hiding Among Local and Foreign Workers in the Middle East’, Journal of Business Ethics, 164(3), pp. 611–625, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4056-2

- Babič, K., Černe, M., Škerlavaj, M., & Zhang, P. (2018). The interplay among prosocial motivation, cultural tightness, and uncertainty avoidance in predicting knowledge hiding. Economic & Business Review, 20(3). 395–422. doi: https://doi.org/10.15458/85451.71

- Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900105

- Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2011). Trends in family business research. Small Business Economics, 40(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9362-3

- Bhattacharya, S., & Sharma, P. (2019). Dilemma between ‘it’s my or it’s my organization’s territory’: Antecedent to knowledge hiding in indian knowledge base industry. International Journal of Knowledge Management (IJKM), 15(3), 24–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.4018/IJKM.2019070102

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x

- Bock, G.-W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y.-G., & Lee, J.-N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

- Bogilović, S., Černe, M. and Škerlavaj, M. (2017) ‘Hiding behind a mask ? Cultural intelligence, knowledge hiding, and individual and team creativity’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Routledge, 26(5), pp. 710–723, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1337747

- Bollinger, S. A. and Smith, D. R. (2001) ‘Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 5(1), pp. 8–18, https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13673270110384365

- Brown, G., Lawrence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2005). Territoriality in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.17293710

- Butt, A. S. (2019) ‘Determinants of top ‑ down knowledge hiding in firms: an individual ‑ level perspective’, Asian Business & Management, 20(2), pages 259–279, doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-019-00091-1

- Cabrera, A., & Cabrera, E. F. (2002). Knowledge-sharing dilemmas. Organization Studies, 23(5), 687–710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840602235001

- Callon, M., Law, J. and Rip, A. (1986) Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology. The Macmillan Press, 242 pages, .1007/978–1–349–07408–2

- Casillas, J., & Acedo, F. (2007). Evolution of the intellectual structure of family business literature: A bibliometric study of fbr. Family Business Review, 20(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00092.x

- Černe, M., Nerstad, C. G. L., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2014). What goes around comes around: Knowledge hiding, perceived motivational climate, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 172–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0122

- Černe, M., Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(2), 281–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12132

- Černe, M., Kaše, R. and Škerlavaj, M. (2016) ‘Non-technological innovation research: evaluating the intellectual structure and prospects of an emerging field’, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 32, pp. 69–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2016.02.001

- Chirico, F. (2007) ‘The Accumulation Process of Knowledge in Family Firms’, Electronic Journal of Family Business Studies, 1(1), pp. 62–90.

- Cobo, M. J., López‐Herrera, A. G., Herrera‐Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21525

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Connelly, C. E., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 779–782. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2407

- Connelly, C. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2003). Predictors of employees’ perceptions of knowledge sharing cultures. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(5), 294–301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730310485815

- Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.737

- Connelly, E. C. and Zweig, D. (2015) ‘How perpetrators and targets construe knowledge hiding in organizations’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(3), pp. 479–489.

- Coulson-Thomas, C. (2004) ‘The knowledge entrepreneurship challenge: Moving on from knowledge sharing to knowledge creation and exploitation’, The Learning Organization, 11(1), pp. 84–93, doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470410515742

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Mapping the field of mixed methods research. SAGE publications Sage CA.

- Crocker, J. K. and Snow, A. (1992) ‘The social value of hidden information in adverse selection economies’, Jorunal of Public Economics, 48(3), pp. 317–347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-27279290011-4

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2016). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2016). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Cunningham, J., Seaman, C. and McGuire, D. (2016) ‘Knowledge Sharing in Small Family Firms: A Leadership perspective’, Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(3), pp. 228–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2015.10.002

- Cunningham, J., Seaman, C. and McGuire, D. (2017) ‘Perceptions of Knowledge Sharing Among Small Family Firm Leaders: A Structural Equation Model’, Family Business Review, 30(2), pp. 160–181, .1177/0894486516682667

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge:. How organizations manage what they know: Harvard Business Press.

- Davis, S., & Botkin, J. (1994). The coming of knowledge-based business. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1994/09/the-coming-of-knowledge-based-business

- de Geofroy, Z. and Evans, M. M. (2017) ‘Are Emotionally Intelligent Employees Less Likely to Hide Their Knowledge?’, Knowledge and Process Management, 24(2), 81–95.

- Dedahanov, T. A. and Rhee, J. (2015) ‘Examining the relationships among trust, silence and organizational commitment’, Management Decision, 53(8), pp. 1843–1857, doi:

- Demirkasimoglu, N. (2015) ‘Knowledge Hiding in Academia: Is Personality a Key Factor?’, International Journal of Higher Education, 5(1), 128–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v5n1p128

- Desouza, K. C. and Awazu, Y. (2006) ‘Knowledge management at SMEs: five peculiarities’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(1), pp. 32–43, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270610650085.

- Dupuy, F. (2004) Sharing knowledge: the why and how of organizational change. Palgrave Macmillan, 288 pages, doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230006157

- Edwards, J. S., Ababneh, B., Hall, M., & Shaw, D. (2009). Knowledge management: A review of the field and of or’s contribution. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(1), S114–S125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2008.168

- Evans, M. J., Hendron, G. M. and Oldroyd, B. J. (2015) ‘Withholding the Ace: The Individual- and Unit-Level Performance Effects of Self-Reported and Perceived Knowledge Hoarding’, Organization Science, 26(2), pp. 311–631, doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0945

- Fisher, G. and Aguinis, H. (2017) ‘Using Theory Elaboration to Make Theoretical Advancements’, Organizational Research Methods, 20(3), pp. 438–464, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116689707

- Fong, P. S. W., Men, C., Luo, J., & Jia, R. (2018). Knowledge hiding and team creativity: The contingent role of task interdependence. Management Decision, 56(2), 329–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0778

- Ford, D. P., & Staples, S. (2010). Are full and partial knowledge sharing the same? Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(3), 394–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011050120

- Gagné, M., Tian, A. W., Soo, C., Zhang, B., Ho, K. S. B., & Hosszu, K. (2019). Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: The role of motivating work design. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 783–799. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2364

- Gaviria-Marin, M., Merigó, J. M., & Baier-Fuentes, H. (2019). Knowledge management: A global examination based on bibliometric analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 140, 194–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.006

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Grant, M. R. (1996) ‘Toward a Knowledge-Based Theory of the Firm’, Strategic Management Journal, 17(52), pp. 109–122, 4250171110

- Hansen, M. T. (1999). The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2667032

- He, Q. (1999) ‘Knowledge Discovery Through Co-Word Analysis’, Library Trends, 48(1), pp. 133–159.

- Hernaus, T., Cerne, M., Connelly, C., Vokic, N. P., & Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Evasive knowledge hiding in academia: When competitive individuals are asked to collaborate. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(4), 597–618. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2017-0531

- Huo, W., Cai, Z., Luo, J., Men, C., & Jia, R. (2016). Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: A multi-level study of r&d team’s knowledge hiding behavior. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(5), 880–897. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0451

- Jacso, P. (2005) ‘As we may search – Comparison of major features of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar citation-based and citation-enhanced databases’, Current Science, 89(9), pp. 1537–1547.

- Jha, J. K., & Varkkey, B. (2018). Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: Evidence from the indian r&d professionals. Journal of Knowledge Management 22(4). doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2017-0048

- Jiang, Z., Hu, X., Wang, Z., & Jiang, X. (2019). Knowledge hiding as a barrier to thriving: The mediating role of psychological safety and moderating role of organizational cynicism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 800–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2358

- Kang, S.-W. (2017). Knowledge withholding: Psychological hindrance to the innovation diffusion within an organisation. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 14(1), 144–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2014.24

- Khalid, M. et al. (2018) ‘When and how abusive supervision leads to knowledge hiding behaviors: An Islamic work ethics perspective’, Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 39(6), 794–806.

- Kumar Das, A., & Chakraborty, S. (2018). Knowledge withholding within an organization: The psychological resistance to knowledge sharing linking with territoriality. Journal on Innovation and Sustainability, 9(3): 94–108. RISUS ISSN 2179-3565. doi:https://doi.org/10.24212/2179-3565.2018v9i3p94-108

- Labafi, S. (2017). Knowledge hiding as an obstacle of innovation in organizations a qualitative study of software industry. AD-minister 30, 131–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17230/ad-minister.30.7

- Lilleoere, A.-M. and Hansen, E. H. (2010). ‘Knowledge-sharing enablers and barriers in pharmaceutical research and development’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(1), pp. 53–70.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111108693

- Lin, T.-C., & Huang, -C.-C. (2010). Withholding effort in knowledge contribution: The role of social exchange and social cognitive on project teams. Information & Management, 47(3), 188–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.02.001

- Lopez-Fernandez, M. C., Serrano-Bedia, M. A. and Perez-Perez, M. (2016) ‘Entrepreneurship and Family Firm Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of An Emerging Field’, Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), pp. 622–639.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/JSBM.12161

- Losada-Otálora, M., Peña-García, N., & Sánchez, I. D. (2020). Interpersonal conflict at work and knowledge hiding in service organizations: The mediator role of employee well-being. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 13(1), 63–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-02-2020-0023

- Martens, C. D. P., Lacerda, F. M., Belfort, A. C., & Freitas, H. M. R. D. (2016). Research on entrepreneurial orientation: Current status and future agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(4), 556–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-08-2015-0183

- Mechanic, D. (1962). Sources of power of lower participants in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 7(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2390947

- Morris, A. S. and Van Der Veer Martens, B. (2008) ‘Mapping Research Specialties’, in Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. Libraries Unlimited, 42(1), pp. 213–295.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ARIS.2008.1440420113

- Nonaka, I. (1991) ‘The Knowledge-Creating Company, Harvard Business Review, 69(6), 96–104.

- Offergelt, F., Spörrle, M., Moser, K., & Shaw, J. D. (2019). Leader‐signaled knowledge hiding: Effects on employees’ job attitudes and empowerment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 819–833. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2343

- Osareh, F. (1996). Bibliometrics, citation anatysis and co-citation analysis: A review of literature ii. Libri, 46(4), 217–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/libr.1996.46.4.217

- Paruchuri, S., & Awate, S. (2017). Organizational knowledge networks and local search: The role of intra‐organizational inventor networks. Strategic Management Journal, 38(3), 657–675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2516

- Peng, H. (2013). Why and when do people hide knowledge? Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(3), 398–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2012-0380

- Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2001). Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 298–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378028

- Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2003). The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Review of General Psychology, 7(1), 84–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.7.1.84

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Price, H. K., Harrison, A. D. and Gavin, H. J. (2006) ‘Withholding Inputs in Team Contexts: Member Composition, Interaction Processes, Evaluation Structure, and Social Loafing’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), pp. 1375–1384. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1375

- Randhawa, K., Wilden, R., & Hohberger, J. (2016). A bibliometric review of open innovation: Setting a research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(6), 750–772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12312

- Rey-Martí, A., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Palacios-Marqués, D. (2016). A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1651–1655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.033

- Rhee, Y. W., & Choi, J. N. (2017). Knowledge management behavior and individual creativity: Goal orientations as antecedents and in-group social status as moderating contingency. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 813–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2168

- Riege, A. (2005) ‘Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers managers must consider’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(3), pp. 18–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510602746

- Riley, J. G. (1985). Competition with hidden knowledge. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 958–976. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/261344

- Ruparel, N., & Choubisa, R. (2020). Knowledge hiding in organizations: A retrospective narrative review and the way forward. Dynamic Relationships Management Journal, 9(1), 5–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.17708/DRMJ.2020.v09n01a01

- Schildt, A. H., Zahra, A. S. and Sillanpaa, A. (2006) ‘Scholarly Communities in Entrepreneurship Research: A Co-Citation Analysis’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(3), pp. 399–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2006.00126.X

- Serenko, A. (2019). Knowledge sabotage as an extreme form of counterproductive knowledge behavior: Conceptualization, typology, and empirical demonstration. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(7), 1260–1288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2018-0007

- Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1199–1224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2016-0203

- Singh, S. K. (2019). Territoriality, task performance, and workplace deviance: Empirical evidence on role of knowledge hiding. Journal of Business Research, 97, 10–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.034

- Škerlavaj, M. et al. (2018) ‘Tell me if you can: time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(7), 1489–1509, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2017–0179

- Small, H. (1973) ‘Co-citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 24(4), pp. 265–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.4630240406

- Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 27–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171105

- van Eck, N. J. and Waltman, L. (2010) ‘Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping’, Scientometrics, 84(2), pp. 523–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/S11192-009-0146-3

- Waltman, L., van Eck, N. J. and Noyons, C. M. E. (2010) ‘A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks’, in Journal of Informetrics, 4(4), pp. 629–635. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOI.2010.07.002

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.10.001

- Wang, Y., Han, M. S., Xiang, D., & Hampson, D. P. (2019). The double-edged effects of perceived knowledge hiding: Empirical evidence from the sales context. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(2), 279–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2018-0245

- Webster, J., Brown, G., Zweig, D., Connelly, C. E., Brodt, S. & Sitkin, S. (2008) ‘Beyond knowledge sharing: Withholding knowledge at work’, Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 27(08), pp. 1–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(08)27001-5

- White, H. D., & Griffith, B. C. (1981). Author cocitation: A literature measure of intellectual structure. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 32(3), 163–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630320302

- White, H. D. and Mccain, K. W. (1998) ‘Visualizing a Discipline: An Author Co-Citation Analysis of Information Science, 1972 – 1995’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(4), pp. 327–355. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-4571(19980401)49:4

- Zeleny, M. (1987). Management support systems: Towards integrated knowledge management. Human Systems Management, 7(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-1987-7108

- Zhao, D., & Strotmann, A. (2014). The knowledge base and research front of information science 2006–2010: An author cocitation and bibliographic coupling analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(5), 995–1006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23027

- Zhao, H., Liu, W., Li, J., & Yu, X. (2019). Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and knowledge hiding: T he moderating role of relative leader–member exchange. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 834–848. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2359

- Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2014). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 429–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629

- Zupic, I. and Čater, T. (2015) ‘Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization’, Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), pp. 429–472.