ABSTRACT

Background: Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS) is a rare genetic disorder that is caused by a decrease or an absence of lipoprotein lipase activity. FCS is characterized by marked accumulation of chylomicrons and extreme hypertriglyceridemia, which have major effects on both physical and mental health. To date, there have been no systematic efforts to characterize the impact of chylomicronemia on FCS patients’ lives. In particular, the impact of FCS on the burden of illness (BoI) and quality of life (QoL) has not been fully described in the literature.

Methods: IN-FOCUS was a comprehensive web-based research survey of patients with FCS focused on capturing the BoI and impact on QoL associated with FCS. Sixty patients from the US diagnosed with FCS participated. Patients described multiple symptoms spanning across physical, emotional and cognitive domains.

Results: Patients on average cycled through 5 physicians of varying specialty before being diagnosed with FCS, reflecting a lengthy journey to diagnosis Nearly all respondents indicated that FCS had a major impact on BoI and QoL and significantly influenced their career choice and employment status, and caused significant work loss due to their disease.

Conclusion: FCS imparts a considerable burden across multiple domains with reported impairment on activities of daily living and QoL.

1. Introduction

Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) is a serious and rare genetic disease characterized by persistent extremely high serum triglycerides (TG) that are carried primarily in chylomicrons (dietary lipids) [Citation1]. Chylomicrons are large (~1 micron in diameter) lipoprotein particles that, if elevated, can result in clinically significant manifestations, including severe abdominal pain and acute pancreatitis (AP), which can be fatal or lead to pancreatic damage, resulting in permanent exocrine or endocrine insufficiency [Citation2].

FCS is caused by a marked decrease or absence of lipoprotein lipase activity (LPL), an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of TG in plasma triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Patients with FCS have inherited defects that limit or impair functionality of LPL. These include mutations in, most commonly, the LPL gene, or in genes that encode for proteins necessary for the functionality of the LPL enzyme including APOC2, APOA5, LMF-1, and GPIHBP1 [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4]. New mutations continue to be discovered with ongoing research.

The absence of LPL activity leads to sustained chylomicronemia, lipemic plasma and abnormal blood tests, and clinical effects including eruptive xanthomas, lipemia retinalis, neurocognitive effects, hepatosplenomegaly, and recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, ranging from mild to incapacitating [Citation3,Citation5]. Although the many manifestations of chylomicronemia severely and negatively impact FCS patients, it is the constant threat of potentially fatal AP that constitutes one of the greatest burdens. The consistently high serum TG levels not only lead to a high frequency of AP in FCS patients, but often recurrent AP in up to 50% or more of patients [Citation6]. Repeated episodes of AP may lead to chronic pancreatitis, with its own attendant complications of pancreatic exocrine deficiency [Citation2], leading to digestive issues, steatorrhea and malabsorption, as well as endocrine deficiency, leading to diabetes and all of its complications. Although hypertriglyceridemia is a fairly well-accepted risk factor for cardiovascular disease, there remains ongoing debate about the atherogenecity of chylomicrons, once thought too large to cross the vascular walls. However, cases of CVD have been reported in a number of FCS patients [Citation7,Citation8].

Currently, there is no approved therapy indicated for the treatment of FCS in the USA. FCS symptom management strategies have traditionally focused on aggressively restricting dietary consumption of all dietary fat and simple carbohydrates, abstinence from alcohol, as well as the avoidance of drugs known to raise TG levels such as thiazides, beta-blockers, and estrogen [Citation5,Citation9]. Traditional lipid-lowering therapies such as fish oil, fibrates, and niacin are only minimally effective in the FCS population as in large part they reduce plasma TG levels by reducing hepatic output of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and/or by enhancement of LPL activity [Citation1,Citation4]. In order to reduce the input of TG into plasma in the form of chylomicrons, it is necessary for patients to restrict their total fat intake (e.g. saturated, mono or polyunsaturated) to less than 10–15% of caloric intake or 10–20 g per day [Citation9], the equivalent of approximately one tablespoon of olive oil. However, sustained compliance with such extreme restrictions at every meal throughout a lifetime is difficult even for the most disciplined person, and even with strict compliance, the risk of clinical manifestations including AP may not be sufficiently mitigated [Citation4,Citation10].

While the most acute signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, eruptive xanthomas, and hepatosplenomegaly, and morbidities such as acute and recurrent AP have been well documented in this population, there exists minimal information about the complete inventory of the symptomology associated with FCS, especially the psychosocial and cognitive symptoms, and the translation of these symptoms to diminished quality of life and impairment on ability to work. This article reports the interim results of an ongoing survey, the Investigation of Findings and Observations Captured in Burden of Illness Survey in FCS Patients (IN-FOCUS), a comprehensive research study capturing the Burden of Illness (BoI) associated with FCS in the voice of the patient, a first of a kind survey of this magnitude.

2. Patients and methods

IN-FOCUS was an online, anonymous quantitative research study, conducted with patients diagnosed with FCS. The study utilized a web survey that was approximately 45 min in duration. All research materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Mississippi.

2.1 Study design

IN-FOCUS was designed to capture current and retrospective data about the experience of living with FCS from eligible FCS patients. Specific inclusion criteria for the study were set as referenced below. Study participation was open to eligible patients in many countries globally. The survey was available in multiple languages including English, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Italian as appropriate for the patients’ preferred language, however, the data presented in this manuscript are from an interim analysis of US patients only. Patients were provided the option to complete the online survey over multiple sittings if they preferred and were nominally compensated for their time.

2.2 Questionnaire

As of the writing of this manuscript, there was no validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument for FCS. To develop a novel questionnaire for this study, several existing quality of life (QoL) instruments were consulted to examine QoL domain types tested, such as the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) [Citation11] and the Pancreatitis Quality of Life Instrument (PANQOLI) [Citation12]. Further input from established expert physicians treating patients with FCS, dietitians, and patients with FCS was sought. Patient input was critical in ensuring that symptoms and QoL dimensions specific to the experiences of patients with FCS were included and with language and content that captured the multiple aspects of the disease. The draft questionnaire (research instrument) was pilot tested through direct interviews with patients with FCS to further optimize content, comprehension and completeness.

The questionnaire was comprised of questions divided into sections:

Screening criteria and demographics

Diagnosis

Initial perceptions of FCS

Current symptoms and comorbidities

FCS management

Impact of FCS on personal, social and professional life, on mental and physical health and on diet

Financial impact of living with FCS

2.3 Recruitment and patient sample

Patients were recruited via recruitment flyers, word of mouth (e.g. FCS-treating clinicians informing FCS patients, on-line postings in patient support/advocacy groups), and social media outlets such as Facebook. Physician experts in treating FCS were provided with informational flyers to share with eligible and interested patients.

Upon entering the web-based questionnaire, respondents were required to complete a series of screening questions in order to confirm their eligibility. Inclusion criteria were set as:

≥18 years of age, AND

Physician diagnosis of familial chylomicronemia syndrome, OR Fredrickson type I hyperlipoproteinemia, OR lipoprotein lipase deficiency, OR high TG with a history of pancreatitis, OR high TG with a history of severe abdominal pain requiring hospitalization, AND

Patient-reported fasting TG level ≥750 mg/dL (8.4 mmol/L) in most recent fasting TG test, OR patient-reported fasting TG level <750 mg/dL in most recent fasting TG test WITH self-reported diet management to minimize fat content, AND

Not having participated in a clinical trial for FCS investigational drug(s) in the past 6 months.

In addition to these criteria described above, respondents must have satisfied one of the following 4 criteria:

A personal history of TG-induced AP, in the absence of another known cause, OR

A history of recurrent abdominal pain requiring emergency department visit /hospitalization that was considered to be due to high TG levels, in absence of another known cause, OR

A family history compatible with FCS or Fredrickson type I hyperlipoproteinemia, in the absence of another known cause, OR

Genetic diagnosis consistent with FCS

Patients were excluded if they did not meet any of the above criteria. Moreover, several irrelevant answer choices were included in various screening questions by design, to discretely identify and disqualify nonvalid respondents or ‘professional’ survey takers.

2.4 Statistical analysis and data presentation

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were presented as mean with standard deviation, or median with range in instances where the data appeared skewed. Rating scales were treated as continuous variables for this analysis. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentage of occurrence of each category.

2.5 Patient sample

The data from the web-based survey were collected from US respondents between 24 June 2016 and 18 November 2016. The survey website (www.FCSinfocus.com) had a total of 1,847 visitors. Once on the website, 213 respondents started the questionnaire by completing at least one question in the screening portion. In total, 14 patients were disqualified from participation because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, while 67 completed the screening questions and qualified for the study. Of the 67 patients who qualified for the study, 60 ultimately completed the survey within this time frame.

A diagnosis of FCS, Fredrickson type 1 hyperlipoproteinemia, LPL deficiency, high TG with a history of pancreatitis, and/or high TG with a history of severe abdominal pain requiring hospitalization was made in all patients by a physician. In 67% of patients, this diagnosis was made before or at the age of 10 years old. Further demographic information of the 60 patients is outlined in .

Table 1. Questionnaire topics.

3. Results

3.1 Path to diagnosis

Patients reported a mean of 5 (median = 5, range: 1–30) physicians for their symptoms before being diagnosed with FCS, conveying the lengthy journey to get to a diagnosis and a likely delay in receiving appropriate care. The majority of patients (67%) reported that their symptoms were misdiagnosed before being correctly diagnosed with FCS. The most common misdiagnoses were AP of unknown cause at the time (48%) and hypertriglyceridemia (45%). Half of all patients (50%) reported that hospitalization due to AP specifically led them to seek a diagnosis ().

Table 2. Patient demographics.

3.2 Symptoms and comorbid conditions

Patients were shown a list of 41 potential symptoms associated with FCS, and separately asked to indicate (1) their typical, average symptoms within the past 12 months (Supplements); and (2) symptoms they have experienced at their worst or most severe due to FCS within the past 12 months. These 41 symptoms listed encompassed 3 domains: physical (21), emotional (13), and cognitive (7). Several ‘other’ response options were also included to allow for write-in responses. For each symptom selected, symptom severity (Likert scale rating of 1–7, 1 = ‘Very mild’, 7 = ‘Very severe’) and frequency (Multiple times per day, Daily, Every other day, Twice a week, Once a week, Every other week or Monthly) were also captured.

The mean number of symptoms reported by patients at their worst or most severe form was 7 (; median = 4, range: 1–37). Approximately, one-fifth of patients (21%) experienced >10 symptoms when their FCS symptoms were at their worst or most severe. shows the 16 symptoms that were experienced in their most severe form by ≥20% of the patients, demonstrating the multiple and complex symptomatology that patients with FCS may experience at any given time. A listing of the top symptoms reported can be found in the . This heterogeneity, as patients often present differently, poses challenges for both the diagnosis and treatment of patients with FCS.

Table 3. Path to diagnosis.

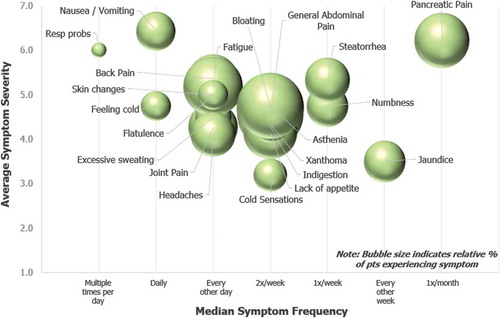

3.2.1 Physical symptoms

shows the incidence, frequency, and severity at which patients experienced physical symptoms in their most severe form. The bubble size reflects the percent of patients reporting each symptom. The 5 most commonly reported symptoms were bloating (35%), generalized abdominal pain (33%), asthenia (33%), fatigue (27%), and indigestion (23%). These symptoms were experienced at a frequency of 2–3 times per week.

Figure 1. Physical Symptoms at their Worst or Most Severe. Patients indicated symptoms experienced in their most severe form over the past 12 months. For each symptom selected, patients indicated symptom severity and frequency. Severity was recorded on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = Very Mild and 7 = Very severe). Frequency was recorded via selection from the following options: Multiple times per day, Daily, Every other day, Twice a week, Once a week, or Every other week. Spheres sizes in chart are proportional to the percent of patients who selected each symptom. The most widely reported physical symptom experienced in its most severe form, bloating, was experienced by 35% of patients.

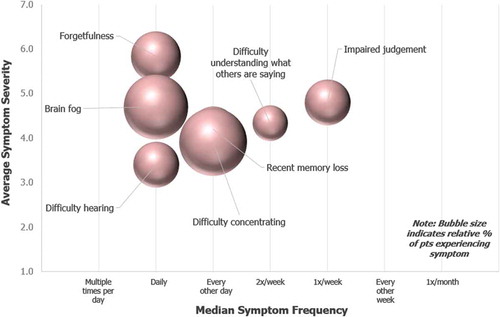

3.2.2 Cognitive symptoms

shows the incidence, frequency, and severity at which patients experienced cognitive symptoms in their most severe form. The 5 most commonly reported symptoms were difficulty concentrating (18%), ‘brain fog’ (17%), forgetfulness (10%), impaired judgment (8%), and recent memory loss (8%). These symptoms were experienced on a daily or weekly basis.

Figure 2. Cognitive Symptoms at their Worst or Most Severe. Patients indicated symptoms experienced in their most severe form over the past 12 months. For each symptom selected, patients indicated symptom severity and frequency. Severity was recorded on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = Very Mild and 7 = Very severe). Frequency was recorded via selection from the following options: Multiple times per day, Daily, Every other day, Twice a week, Once a week, or Every other week. Spheres sizes in chart are proportional to the percent of patients who selected each symptom. The most widely reported cognitive symptom experienced in its most severe form, difficulty concentrating, was experienced by 18% of patients.

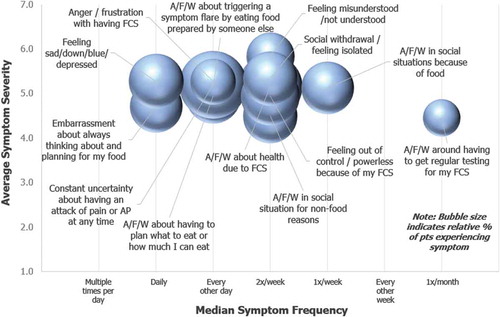

3.2.3 Emotional symptoms

shows the incidence, frequency, and severity at which patients experienced emotional symptoms in their most severe form. The 4 most commonly reported symptoms were constant uncertainty about having an attack of pain or AP at any time (33%), anxiety/fear/worry about my health due to FCS (30%), feeling out of control /powerless because of my FCS (25%). The following symptoms were fifth most common and each experienced by 22% of patients: anxiety/fear/worry about having to plan what to eat or how much I can eat, anxiety/fear/worry in social situations for nonfood reasons, feeling sad/down/blue/depressed, and social withdrawal/feeling isolated. These symptoms were experienced at a frequency of every 1–3 days.

Figure 3. Emotional Symptoms at their Worst or Most Severe. Patients indicated symptoms experienced in their most severe form over the past 12 months. For each symptom selected, patients indicated symptom severity and frequency. Severity was recorded on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = Very Mild and 7 = Very severe). Frequency was recorded via selection from the following options: Multiple times per day, Daily, Every other day, Twice a week, Once a week, or Every other week. Spheres sizes in chart are proportional to the percent of patients who selected each symptom. The most widely reported emotional symptom experienced in its most severe form, constant uncertainty about having an attack of pain or AP at any time, was experienced by 33% of patients.

3.2.4 Comorbid conditions

Nearly all (98%) patients reported having at least 1 FCS-related comorbidity (58%, 18%, 11%, and 12% reported having developed 1, 2, 3, and 4+ FCS-related comorbidities respectively). AP was the most common comorbidity (42%). Eight separate comorbidities were reported by ≥10% of patients each ().

Table 4. Top symptoms at most severe symptomology.

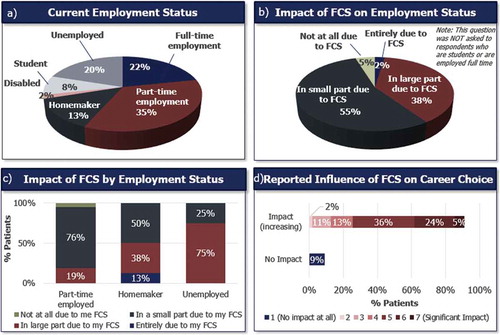

3.2.5 Impact on employment

Patients were asked to report their current employment status. If not currently a student or employed full- or part-time, patients were asked if they had previously been employed. Patients were also asked a series of questions to assess whether FCS has had any impact on their career choice, employment status, or their ability to fulfill responsibilities at work.

The current employment status of patients is shown in ). Nearly all (95%) patients who were employed part time, disabled or homemakers reported that their current employment status was in some part influenced by FCS ()). All patients who are currently homemakers or unemployed, reported that their current employment status was in some part due to their FCS ()).

Figure 4. Impact of FCS on employment status and career choice. Patients indicated their current employment status (a), and the impact of FCS on their employment status (b). Impact of FCS on employment status of homemakers and unemployed patients (c), and influence of FCS on patients’ career choice reported using a 1–7 Likert scale where 1 = No impact at all and 7 = Significant impact (d).

Patients’ choice of career was also impacted by their FCS ()). When asked to rate the impact of FCS on their career choice using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = No impact at all, 7 = Significant impact), 91% of patients reported that FCS had some impact on their career choice.

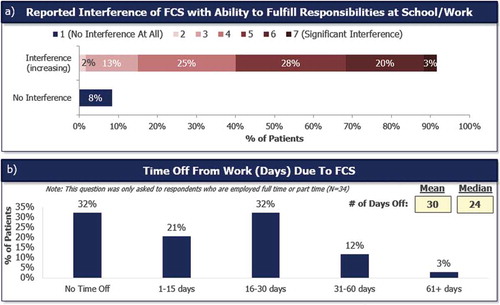

Most patients (92%) reported that FCS had impacted their ability to fulfill their responsibilities at school or work ()). FCS had directly caused 68% of full- or part-time employed patients to take time off from work ()). Full- and part-time employed patients missed a mean of 30 (median = 24, range: 0–210) days of work in the past 12 months because of their FCS.

Figure 5. Impact of FCS on ability to perform responsibilities at school or work and time off from work due to FCS. Impact of FCS with ability to fulfill responsibilities at school or work (a). Responses were recorded on a 1–7 Likert scale where 1 = No impact at all and 7 = significant impact. Number of days taken off work in the past 12 months, asked to patients who were full- or part-time employed (N = 34) (b).

4. Discussion

The findings of this survey reveal an inventory of symptomology and comorbidities that impart major burden on patients’ life and impact on patients’ employment status and their perceived productivity in the workplace. Patients had indicated that they had cycled through an average of 5 physicians, ranging from 1 to 30, before receiving a diagnosis of FCS which highlights the lack of awareness among the physician community, and the need for physician education. Moreover, the proportion of patients who received a misdiagnosis for their FCS symptoms underscore the lengthy journey to a diagnosis and the burden shouldered by the patients and caregivers. In a study conducted by Engel et al. [Citation13], 44% of the patients that had been diagnosed with a rare disease agreed that as a result of a delay in their diagnosis, proper care and treatment was delayed, and the impact of their condition had been negative. Due to the heterogeneous nature of FCS and the limited guidance in the literature on diagnostic criteria, it is not surprising that physicians who encounter FCS may not be well versed on the diagnosis of this rare condition. Of interest was the high number of respondents (70%) who were aware of a relative diagnosed with FCS (), although we expanded the search from just parents to aunts/uncles, parents, grandparents, siblings and cousins. It is of further interest, that 10 of the 11 patients who were diagnosed by the first doctor they saw (data not shown), had a near relative with a FCS diagnosis, perhaps raising awareness of the disease as a possible diagnosis and thus minimizing their diagnostic journeys.

Patients must also contend with the potential long-term consequences of their FCS. Almost all patients in the survey reported having developed at least 1 comorbid condition because of their FCS. Forty-one percent of the patients reported having developed 2 or more comorbid conditions. Consistent with the literature, patients with FCS experience a high risk of developing recurrent AP and death from pancreatitis-related complications, known to be associated with a relatively high risk of mortality [Citation3]. Patients also reported fatty liver disease, cholecystectomy and diabetes [Citation6,Citation14]. Further, 17% of the patients had co-morbid chronic pancreatitis, characterized in the literature to have both significant physical and mental QoL consequences [Citation15]. These comorbid conditions further add to the physical and emotional burden imposed on patients living with FCS. Moreover, optimal management of FCS would benefit from better understanding of the nature and extent of its common comorbid conditions.

Beyond the immediate and direct burden associated with symptomatic episodes of FCS, there is also a broader impact on employment. Over 90% of the patients with FCS reported that their disease had impacted their career choice. Further to this point, greater than one-third of patients reported not pursuing their ideal career because they felt too fatigued to pursue a demanding career, required travel, or because they felt that they could only think clearly on ‘good days.’ This suggests that patients may experience diminished career fulfillment and/or the opportunity costs of income foregone as a result of perceived incapacity. This is particularly notable given that the patients in the survey had a mean age of 36, which is a most economically productive period of life.

Despite selecting careers to accommodate FCS-related limitations, >90% of the survey respondents reported that FCS had interfered with their ability to fulfill responsibilities at school or work. Over two-thirds of the patients that were employed either full- or part-time reported having taken up to 30 days off from work or school due to FCS. Based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average American took 3.5 sick days off from work and depending on the number of years worked, employees were granted an average of 9 days of sick leave by employers [Citation16]. The average number of sick days missed due to FCS is likely to extend beyond the amount of annual sick leave provided to employees in the USA. Furthermore, 95% of patients who identified as unemployed, disabled, employed part-time, or homemakers attributed at least some part of their current employment status to their FCS. Combined with the 92% who report that their FCS interferes with their ability to fulfill their responsibilities at work, the results from this survey corroborate with job productivity and employment studies. These studies indicate that poor health status increase work-related absences and reduce overall work performance; in turn creating a substantial burden on both the patients as well as their employers [Citation18]. Given the degree to which FCS interferes with patients’ ability to work, it is not surprising that only 22% of the patients were employed full-time and 35% were employed part-time. Compared to the age-matched employment rate in the USA of 80% [Citation17], the low rates of employment among patients serve to support the categorization of how FCS has impacted various aspects of their career. Aside from providing an income, work holds an important value on personal identity, social values and recognition. Work also helps to develop community networks and contributes to an individual’s self-worth. Research on work productivity and performance have demonstrated that an individual’s participation in the workplace plays an important role in the individual’s overall self-esteem [Citation15]. As illustrated in this survey, FCS had a negative impact on patients’ career choice, employment status and perceived work productivity in numerous ways.

4.1 Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. The self-reported nature of the survey precludes independent verification of facts and experiences provided. It is also possible that there is a selection bias favoring those who are willing to share sensitive health information and are interested in documenting symptomology for scientific research. Recruitment was conducted mainly by word of mouth and referrals within FCS patient groups and organizations, and it is possible the sample may represent only a subset of the FCS population who are part of such networks and organizations. Further, the interim analysis only included survey respondents from the USA and may not represent patients with FCS on a global scale. Full survey results, including patients from 10 countries, will be presented in a future publication.

5. Conclusion

While the available literature discusses the physical manifestations associated with FCS, there is little, if any discussion on the emotional and cognitive symptomology of FCS and the potential ramifications on patients’ lives. The scarcity of data limits patient, caregiver, and physician abilities to accurately assess the impact of FCS. The present study examined the burden of illness in 60 patients with FCS, which is both the first and the largest study to investigate the psychosocial and the cognitive symptoms, and the comorbidities associated with FCS and its impact on employment status. A better understanding and characterization in the burden of illness associated with FCS may potentially provide new insights to address the challenges while identifying a point of reference to support diagnosis. Results from this survey should be used to inform healthcare providers of the implications of patients’ symptom burden and the individualized nature of disease management. Further research is merited to identify formal and codified ways providers could use to efficiently and effectively diagnose FCS. The research also highlights a clear unmet medical need for more effective treatment options.

Key issues

Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS), is a rare genetic disorder with significantly diminished activity or presence of lipoprotein lipase, the enzyme responsible for metabolism of serum triglycerides

Burden of disease in FCS in the extant literature has focused mainly on the physical symptoms, such as acute pancreatitis, but the holistic burden including cognitive and psychosocial domains from the patients’ perspective has not been fully characterized.

Of the 60 respondents in IN-FOCUS, 55% were male and 45% female with an average age of 36. The majority of respondents were between 20 and 40 years of age.

Respondents saw an average of 5 physicians (range: 1–30) before receiving a diagnosis of FCS, conveying the lengthy journey to receive a diagnosis and reflecting the opportunity to enhance clinician recognition of FCS

Patients reported symptoms covering physical, emotional (ie psychosocial) and cognitive domains. All of the symptoms described below occurred daily to several times per week, and were moderately to very severe in magnitude.

Commonly expressed physical symptoms included GI symptoms of generalized abdominal pain, bloating, indigestion and lack of appetite as well as asthenia (generalized weakness) and fatigue.

Commonly expressed emotional symptoms included anxiety/fear/worry about their overall health due to FCS, constant uncertainly about having an attack of pain or acute pancreatitis at any time, embarrassment about always thinking about and planning for food, and anxiety/fear worry about eating food prepared by someone else. In addition, 22% of patients reported depressive episodes, much greater than the 6.7% in the general adult US population.

Commonly expressed cognitive symptoms included difficulty concentrating, ‘brain fog’ (ie lack of thought clarity), impaired judgment, forgetfulness and recent memory loss.

Only 22% of patients reported full time employment and 20% were unemployed (compared with national average of 4.9% unemployment

Respondents noted time off from work due to FCS to range from 0–61+ days with a mean of 30 days in the past 12 months. By comparison, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics noted an average absence of 4–5 days per calendar year.

Only 8% of patients responded that FCS did NOT interfere with their ability to fulfill responsibilities at school/work. 92% noted varying levels of interference, with 51% reporting moderate to extremely significant interference.

Taken together, the burden of FCS expands well beyond the physical aspects captured in the literature, including psychosocial, emotional and cognitive burdens.

Declaration of interest

M. Davidson is a scientific advisory board member of Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck and Sanofi, Regeneron. M. Stevenson is an employee of Akcea Therapeutics. A. Hsieh is an employee of Akcea Therapeutics. Z. Ahmad has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Regeneron and the FH Foundation, and has received honorarium from Amgen and Sanofi, Regeneron. C. Crawson is an employee of Trinity Partners. J. Witztum is a consultant for Ionis, Cymbay, Prometheus and Intercept Pharma. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize and thank the following individuals for their contributions to the design, execution, and analysis of this study:

Jill Prawer: Patient, Founder and Chair of LPLD Alliance.

Nandini Hadker and Lachlan Hanbury-Brown, Trinity Partners.

Maria Bella, MS, RD, CDN, Clinical Nutrition Coordinator, NYU School of Medicine

Thanks to all other contributors, including, critically, the patients whose voice and feedback have enabled a characterization of holistic burden of FCS.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brahm AJ, Hegele RA. Chylomicronaemia--current diagnosis and future therapies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(6):352–362.

- Symersky T, Van Hoorn B, Masclee AA. The outcome of a long-term follow-up of pancreatic function after recovery from acute pancreatitis. J Pancreas. 2006;7(4):447–453.

- Ahmad Z, Halter R, Stevenson M. Building a better understanding of the burden of disease in familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(1):1–3.

- Stroes E, Moulin P, Parhofer KG, et al. Diagnostic algorithm for familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Atheroscler Supp. 2016;23:1–7.

- Brunzell J. Familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency. In: Pagon RA, editor. Gene reviews- NCBI bookshelf. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2017.

- Gaudet D, Blom D, Bruckert E, et al. Acute pancreatitis is highly prevalent and complications can be fatal in patients with familial chylomicronemia: results from a survey of lipidologists. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):680–681.

- Nordestgaard B. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ Res. 2016;118:547–563.

- Véniant MM, Beigneux AP, Bensadoun A, et al. Lipoprotein size and susceptibility to atherosclerosis- insights from genetically modified mouse models. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(3):174–189.

- Valdivielso P, Ramírez-Bueno A, Ewald N. Current knowledge of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(8):689–694.

- Češka R, Štulc T, Votavová L, et al. [Hyperlipoproteinemia and dyslipidemia as rare diseases. Diagnostics and treatment]. Vnitr Lek. 2016 Fall;62(11):887–894.

- Hays RD. The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) measures of patient adherence. 1994 [cited 2016 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.rand.org/health/surveys/MOS.adherence.measures.pdf.

- Wassef WY, Bova CA, Barton BA, et al. Pancreatitis quality of life instrument: development of a new instrument. SAGE Open Med. 2014;2:2050312114520856.

- Engel PA, Bagal S, Broback M, et al. Physician and patient perceptions regarding physician training in rare diseases: the need for stronger educational initiatives for physicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;1(2):1–15.

- Brown A, Gaudet D, Gelrud A, et al. The burden and psychosocial consequences of living with familial chylomicronemia syndrome: patient and caregiver perspective. Poster session presented at: American Society of Preventive Cardiology; 2016 Sep 16–18; Boca Raton, FL.

- Amann ST, Yadav D, Barmada MM, et al. Physical and mental quality of life in chronic pancreatitis: a case-control study from the North American Pancreatitis Study 2 cohort. Pancreas. 2013;42(2):293–300.

- bls.gov [Internet]. Washington (DC): United States Department of Labor; [cited 2017 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/bls/employment.htm.

- Mitchell RJ, Bates P. Measuring health-related productivity loss. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14(2):93–98.

- Doyle C, Kavanagh P, Metclafe O, et al. Health impacts of employment: a review. Dublin (Ireland): The Institute of Public Health in Ireland; 2005.

Appendix

Table A1. Top comorbidities due to FCS.