ABSTRACT

Emotion-focused therapy for couples (EFT-C) is therapy which has a substantial evidence base both for process and outcome studies. However, to date there have been no in-depth empirical case studies that track interactional and emotional transformation in the couple, minute-to-minute, across the entire course of therapy. This case study aimed to observe the interactional transformation and emotional transformation in a couple over 11 sessions of EFT-C therapy. Videos of each session were analyzed using theoretically informed qualitative psychotherapy research. Results showed clients presenting with a negative interactional pattern, which appeared to be composed of two separate but linked cycles. Over the course of treatment, the clients presented with secondary emotions and behaviors including criticism and withdrawal. The individuals within the couple progressed at different rates through the expression of core pain and unmet needs, and after several sessions they were able to give and receive compassion to each other. They also showed signs of beginning to self-soothe more effectively and let go of some pain. The expression of assertive or healthy anger was found to be particularly important for the change in their interaction. Strengths, limitations and ideas for future research are discussed.

Emotion-focused therapy for couples (EFT-C) (also known as emotionally-focused therapy for couples, or EFT) was first developed by Greenberg and Johnson in the 1980s (Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988; Johnson & Greenberg, Citation1985a, Citation1985b), using a humanistic, experiential approach to focus on the emotional processes between partners. The experiential discovery and transformation of emotion in session was combined with a systems theory understanding of interactional cycles between partners (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008). EFT-C proposes that negative interaction cycles develop as follows: one partner enacts a secondary emotion or behavior (e.g. blaming criticism) which is a defensive reaction to their painful underlying primary emotion (e.g. feeling abandoned or not valued). This secondary enactment triggers a primary emotion in their partner (e.g. a feeling of sadness or shame) which then prompts them to respond with a secondary emotion or behavior (e.g. withdrawing). The act of withdrawing exacerbates the first partner’s feeling of abandonment or not being valued, so they respond with more criticism, and the cycle perpetuates. This cycle can take many idiosyncratic forms depending on the types of primary and secondary emotions that are enacted, but the basic dynamics remain the same. The cycle leads to high emotional and behavioral reactivity, dysregulation, and a feeling of invalidation for both partners (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008).

The therapist’s task is to help the couple recognize the interactive cycle as the problem (rather than each other) and work together to express and transform the underlying emotions using more adaptive emotions and responses from their partner (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008; Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988; Johnson, Citation2020). Promoting awareness and expression of primary emotions (often ‘wounds’ from childhood or other relationships) helps to interrupt the cycle of blame and allows the possibility of validation, closeness, empathy and intimacy, thus hopefully creating more positive interactional cycles (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008). Emotion is considered both a target and an agent for change (Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988).

EFT-C research since the 1980s has examined therapy outcomes and in-session processes to identify both the effectiveness of EFT-C overall, and specific tasks, interventions, and therapist behaviors that contribute to its effectiveness (Wiebe & Johnson, Citation2016; Woldarsky Meneses & McKinnon, Citation2019). Despite this wealth of research, there have been only limited empirical case studies of EFT-C, examining the whole sequence of change or other central therapeutic processes for a couple as treatment progresses (e.g. Naaman et al., Citation2005; Welch et al., Citation2019). The current study aimed to use case study methodology and set out to observe: the moment-by-moment in-session transformation of underlying emotions, vulnerabilities, and needs; the transformation of the negative cycle of interaction; and the emergence of restructured, more adaptive interactions of a couple in treatment.

Studies of individual EFT have tracked sequential emotional transformation to identify the process roughly following a sequence from secondary emotion to underlying chronic maladaptive primary emotions, to unmet needs and finally adaptive emotional response (Pascual Leone & Greenberg, Citation2007). We wanted to track this process in the context of a potential interactional transformation (e.g. revealing an underlying vulnerability and receiving adaptive response to it) between a couple, along with their individual transformations.

The data used in this study were collected as part of a series of studies by Greenberg and colleagues (see e.g. Greenberg et al., Citation2010; McKinnon & Greenberg, Citation2013; Woldarsky Meneses & Greenberg, Citation2011), investigating recovery from emotional injuries in couples. Emotional injuries (sometimes called attachment injuries) are described as events in which one partner feels abandoned or betrayed, creating anger and hurt which lasts for months or years. An affair is a common example of such an injury, but other events can create lasting damage, such as being unsupported during a crisis. These injuries damage the emotional bond between the partners as they relate to attachment and identity recognition (Greenberg et al., Citation2010).

Theory-building case study research offers the opportunity to examine valuable moments in therapeutic practice and use these observations to further understand and refine both theory and future practice (Stiles, Citation2007). This study aims to illuminate the in-session transformation of emotions for the individuals and the restructuring of the interactional cycle for the couple in order to demonstrate how this case aligns with the EFT theory. Our aim was to qualitatively analyze moment-to-moment processes (across all sessions) in a case of EFT-C therapy and examine (a) the sequential transformation of the interactional cycle between the couple, (b) the sequential process of emotional transformation in each individual, and (c) the interplay of interactional and emotional transformation.

Method

Participants

This research used audio-visual recordings and transcripts of a course of emotion-focused therapy with one couple and one therapist. There were a total of 11 sessions. These recordings were gathered as part of the York Emotional Injury Project (see Greenberg et al., Citation2010). Descriptions of the participant recruitment methods and consent are outlined in the original papers describing the project (see Greenberg et al., Citation2010; McKinnon & Greenberg, Citation2013; Woldarsky Meneses & Greenberg, Citation2011). The study was approved by the Office of Research Ethics at York University.

Selected case for this study

A total of 37 couples participated in the York Emotional Injury Project (the results of the first 20 are published in Greenberg et al., Citation2010). One couple was selected for this case study because their self-report measures after the 11 sessions of therapy indicated a successful outcome, and because the therapist was Professor Les Greenberg, one of the originators of emotion-focused couple therapy. The couple (Phil & Jenny – pseudonyms) was a white, heterosexual couple, not married but cohabiting for more than 10 years. The female in this couple was identified as the injured party, following the male partner’s affair with a colleague which had lasted approximately one year, while his wife was pregnant. The affair had ended several years before the commencement of this therapy, although the couple had previously had other sessions of therapy (some details have been altered to mask their identity). The therapist for this case study was Professor Les Greenberg, an experienced therapist, registered psychologist, and one of the original creators of EFT and EFT for couples (e.g. Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008; Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988).

Outcome measures

Participants completed several self-report measures approximately one week prior to start of therapy, and then again approximately one week following their final session. The measures were used to track changes in forgiveness, trust, unfinished business, and general relationship adjustment. Not all measures were examined for the purpose of the current study as some were outside the scope of this study. The following measures were examined: Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, Citation1976) and Enright Forgiveness Inventory (EFI; Enright et al., Citation2000). In terms of DAS, the couple featured in this study has self-reported DAS scores listed in .

Table 1. Dyadic Adjustment Scale scores for the current case and means for the whole sample from Greenberg et al. (Citation2010).

At the end of therapy, they both showed recovery (clinically significant change) - above the cutoff for distress and with reliable change index increase of more than 5 (Johnson & Talitman, Citation1997). Phil’s post-treatment score was approximately one and a half standard deviations above the mean of the injured group (see ). Jenny’s post-treatment score was also more than one standard deviation above the mean of the injured group (see ). At 3-month follow-up, their scores had reverted close to their pre-therapy baselines, indicating they had deteriorated. Some possible reasons for this will be discussed in the next section.

The scores on the EFI in indicate an increase in forgiveness from Jenny to Phil post-treatment. They both started somewhat above the mean for their respective groups pre-therapy. By the end of therapy, they had both shown an increase in forgiveness (as measured by EFI) to approximately 1 standard deviation above the mean. Their scores on the ‘forgiven’ and ‘feel forgiven’ single items of the EFI also show an increase from the mid-range (3) to completely forgiven (5) (the single item scale uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = completely). At three month follow-up, the scores had deteriorated in a parallel manner with the scores on the DAS for this couple, back to the pre-treatment baseline. We do not have information about what happened post-therapy in the couple’s interaction that might explain this deterioration. We will cover some potential causes in the discussion of this paper.

Table 2. Scores on the Enright Forgiveness Inventory for the current case and means for the whole sample.

Procedure

The primary research team consisted of the first author (JD), a final year Doctorate in Counselling Psychology student; and the second author (LT), an experienced EFT therapist and psychologist. The analysis was reviewed and discussed with the 3rd author (RG). Finally, the results of analysis were reviewed by the 4th author (LG), one of the original developers of EFT-C.

Each session was viewed carefully (each 60 minute session on video with an available transcript took 4–5 hours for the initial analysis) by the primary research team, using generic theoretically-informed qualitative analysis (Elliott & Timulak, Citation2021; Hissa & Timulak, Citation2020) to note the progress of therapy from moment to moment. Sessions were analyzed in terms of the couple’s interactional positions and their transformation (interactional cycle and its transformation), as well as from the perspective of the individuals’ underlying emotional pain and its transformation. This was done using the theoretical lenses of emotion-focused couples therapy (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008; Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988), EFT case formulation (Goldman & Greenberg, Citation2013; Timulak & Pascual Leone, Citation2015), and emotion transformation theory developed in the context of individual EFT (Pascual Leone & Greenberg, Citation2007; Timulak & Pascual Leone, Citation2015).

The research team paid particular attention to exchanges or events noted in . All relevant observations were recorded. The team observed moment-to-moment couple interactions in terms of problematic interactional and emotional functioning as well as any signs of theoretically productive processes that suggested more constructive interaction and/or emotional processing of the partners. A tentative formulation of the problematic interactional cycle(s) between the partners based on the enacted or reported interactions was developed iteratively as the sessions progressed. Any observations that suggested constructive transformational interactional and/or emotional processes in the cycle were also noted.

Table 3. Theoretically relevant processes or events noted in therapy sessions.

Events with a higher emotional arousal (loosely based on the CEAS-III; Warwar & Greenberg, Citation1999) that represented either an enactment of a problematic interactional position or constructive movement in terms of transforming the problematic cycle were noted in particular. Therapist’s interventions which were involved in clarifying or transforming problematic cycles and emotions were also recorded.

All the videos were watched again by the first author and summaries of the researchers’ observations compiled for each therapy session along with diagrams capturing the interactions and emotional processing for each session. These session summaries were reviewed by the 2nd author and revised and then by the 3rd and 4th author whose comments were also incorporated. These summaries were then used to create composite .

Results

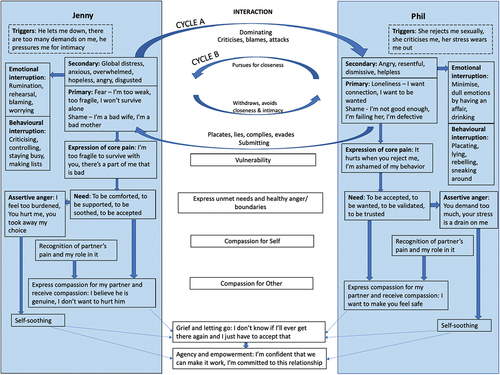

The analysis was done in two stages: first chronologically, to capture the sequence of changes, and then according to EFT theoretical concepts captured in . This paper focuses on the latter. shows the sequence of interactional and emotional change, with change over time depicted vertically moving down the page.

Interactional cycles and their transformation

The research team observed two interactional cycles. Each partner had a dominant, more painful primary emotion which drove one cycle, in which the other partner responded with a less dominant but still core primary maladaptive emotion, to enable the cycle to continue. The cycles were linked and at times overlapped.

For Jenny, her dominant primary emotion appeared to be fear/insecurity – she feared that she would lose control, that terrible things would happen, and that she was too fragile and weak to survive or protect herself (see that captures the cycle presentation and also its transformation) – the injury of the past affair was directly linked to this vulnerability. This drove the first interactional cycle. Jenny (see ) expressed her underlying fear in terms of secondary emotions of overwhelm and anger relating to their busy lives: ‘I do it all! I carry the burden all by myself and I don’t feel like he carries any of it!’ (Session 2, min. 17). She often expressed this feeling of overwhelm in an emotionally heightened way, crying and speaking in a high-pitched tone. Jenny’s fear was triggered by Phil letting her down or not supporting her worries, by demands placed on her from others (e.g. her mother), or by general life stress. She expressed a deep unmet need to be able to rely on someone and was constantly worried that Phil was not dependable or responsible enough.

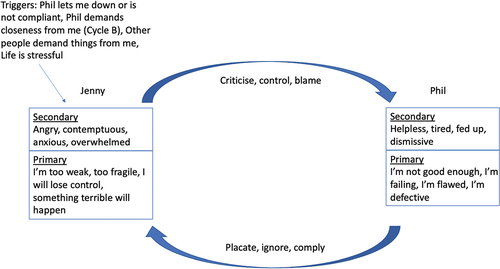

Jenny’s fear led her to try to control and criticize Phil so that he would do things her way. This stirred up Phil’s primary feeling of shame/inadequacy. Mostly, he responded by placating Jenny and dodging tasks, submitting to Jenny’s wishes and sometimes secretly rebelling or resisting. This established an influence cycle of dominate-submit or overfunction-underfunction (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008), where Jenny constantly tried to maintain a one-up position by criticizing Phil and overmanaging their lives, and Phil submitted to her wishes, feeling inadequate, but also fueling her fear by being inauthentic in his support. This cycle, which the research team labeled ‘Cycle A’ (see ) was the focus of the discussion in sessions 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9. These discussions were usually initiated by Jenny in response to one of the triggers named above. ( near here)

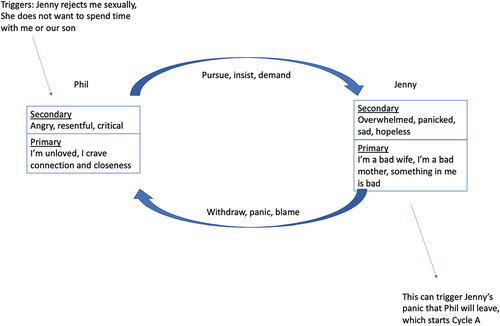

A second cycle observed, ‘Cycle B’ (see ), was driven by Phil’s primary maladaptive emotions (core pain) of loneliness/loss and wanting to feel loved and cared for. This feeling was triggered by Jenny rejecting him sexually or sometimes emotionally, for example as described in session 2 when Phil felt that Jenny didn’t spend enough time with him or their son, and session 4 where he expressed that she didn’t support him emotionally with work problems or offer him praise. When Jenny rejected him, Phil responded with quiet anger, criticism, or cold withdrawal. This provoked Jenny’s other primary emotion of inadequacy, a feeling that she was a bad wife or mother and was unable to make Phil happy. Her secondary emotions as a result of this were anger, despair, hopelessness and general distress. It also indirectly triggered her other primary emotion of fear/insecurity as she was afraid that her inadequacy would cause Phil to leave. Cycle B, which could be labeled a pursuer-distancer cycle, was the focus of the discussion in session 2, parts of sessions 3 and 4, 6, 10 and 11.

One cycle sometimes triggered the other, such as in session 3, which began with a focus on Jenny’s feeling that Phil was unreliable and wouldn’t stick around. Her need in this cycle was for control and safety. She spoke about her fears that the family would dissolve, and that she would be left alone to raise their child or children. She was highly emotionally aroused, crying and speaking in a fast, high voice as she described needing to feel supported. Later in the session, she voiced a fear that part of the reason Phil might leave was that she couldn’t meet his needs for intimacy and sex, and this made her feel inadequate. From her point of view, this appeared to be a real concern, but it was secondary to the fear/insecurity that she would lose control of the family.

When Phil was asked to name what he wanted from Jenny, his answer was always more sex and intimacy. This unmet need was his main driver and the thing that caused the deepest pain for him. Although Jenny’s criticism and anxious worrying were stressful and unpleasant for him, he seemed to have accepted this. In session 10, he reported that the only thing he really wanted to change was an increase in sex and intimacy.

Cycle A was the more explored cycle in therapy, as it related more directly to Phil’s betrayal of Jenny through the affair. This cycle was more resolved by the end of treatment. With the therapist’s encouragement, Phil learned to assert himself rather than always submitting to Jenny, and she became more aware of how her attacking critical stance was alienating to Phil and drove him to withdraw or placate, which fueled her mistrust. They showed clear signs in the last few sessions of changing this interaction, with Phil feeling empowered to stand up to her, and Jenny trying to tolerate this and recognize the impact of her stress on Phil, although she often collapsed to blaming and hopelessness (e.g. Session 10). It appeared the comfort of the known (complaining you let me down) was preferred to the unknown (I am panicked, and I need to find a way of soothing myself without controlling you.)

Cycle B, on the other hand, was not really resolved by the end of treatment. Session 11 centered on a discussion of how this felt like a continuing problem for both parties. The pain of rejection or the sadness of loss for Phil was not really unfolded in detail. Allowing Jenny to understand the depth of his sadness and his need for connection might have created more compassion and helped to transform her feelings more completely. It was also not clearly established or fully explored what blocked Jenny from enjoying their sexual intimacy, a dynamic which they both acknowledged was present before the affair.

Emotional transformation

Primary maladaptive emotions

Jenny’s most poignant primary emotion was a fear/insecurity that she would be left alone and that she would not survive, due to being too fragile. This fear/insecurity was activated frequently in situations where she felt Phil was unreliable or unsupportive, or when she felt too many external demands. Her fear prevented her from moving forward.

Jenny: ‘I still feel! (T: right), I still feel! - that – I can’t depend on you. Even though you’ve made changes I still don’t feel like I can, I guess ultimately’. (Session 4, min. 28).

Jenny feared that Phil was not reliable on a day-to-day basis, and she also feared that he was not fully committed to her (which was linked to the injury for which the couple sought therapy). When this primary emotion was activated, Jenny’s tendency was to express secondary emotions of anger and contempt toward Phil.

Jenny’s other, less dominant, primary emotion was a feeling of shame/inadequacy of being a bad wife and mother and not being able to make Phil happy. This also fed into her fear of him leaving. This core pain was activated when Phil pursued sexual intimacy with her, a regular source of conflict for the couple. It was also related to her emotional availability for their son, something which Phil criticized. She described experiencing his anger due to her failure to make him happy:

Jenny: ‘I mean I feel that – I just, am, incapable of being the partner that he needs and the mother that he thinks I, I need to be’. (Session 3, min. 2).

Jenny’s primary emotions were explicitly linked later in session 3 as Jenny discussed her difficulty managing her emotions when Phil seemed to be angry with her:

Therapist: So, you’re saying to him ‘I feel like I’ll never be able to live up to the kind of ideal you set.’

Jenny: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

Therapist: That must be an awfully disappointing and painful sort of feeling to have, right? I mean I understand you have to handle it by withdrawing and even getting angry but actually it feels like ‘I’m failing to be the person you want me to be.’

Jenny: Yes, it - it’s part of it - but I think you know, the other piece that I feel is, I feel, um, afraid. That our family will dissolve. Like I feel fear too, I feel fear. (Session 3, min. 7).

As therapy progressed, Jenny began to take more ownership for her primary emotions and the impact that they had on her relationship. She was able to recognize them more quickly. She was able to soften her blaming stance toward Phil. However, her underlying fear/insecurity and shame/inadequacy remained crippling.

Jenny: I’m going to need a lot more time! You know, because, um, I just think with time I’ll feel more secure um, (T: okay) and there’s nothing that (sigh) you can do differently or say differently I think other than what you’re doing now. (Session 10, min. 40).

The more explored primary emotion for Phil was one of shame/inadequacy or being not good enough, particularly activated by Jenny’s criticism. While Phil often covered this pain with a secondary dismissiveness or an uninterested stance (e.g. forgetting the question or yawning repeatedly in session while Jenny was criticizing him), at times he expressed poignantly the core pain he felt from her words: ‘She says she wants me to be a different person than what I am … like there’s something wrong with me … ’ (Session 6, min. 39). This underlying sense of shame seemed to come partially from Phil’s childhood, but also related to his betrayal of Jenny with an extramarital affair. This was an additional and more specific source of shame, and Phil’s expression of the pain brought by this shame was a turning point in the treatment, in session 7.

Phil’s most poignant primary maladaptive emotion was a feeling of loneliness and being unloved, although this was not explored as thoroughly as his shame. It was activated by Jenny’s non-availability sexually, but also when she failed to support him, for example when he described work troubles and she responded by agreeing with his boss (Session 6), although this was also linked to his shame. When she rejected him, he felt hurt and unwanted, which he covered with redirected anger, withdrawal, or sometimes with criticism of Jenny’s parenting. As the therapy was focused on the resolution of emotional injury, Phil’s shame (a sense of inadequacy that he failed Jenny, but also a chronic sense of inadequacy or being ‘not good enough’), was explored more than this underlying loneliness. Further sessions might have been able to identify whether this primary loneliness and secondary anger were part of the dominant cycle or represented a second cycle (cycle B) in their relationship.

The expression of core pain and unmet needs

Phil and Jenny expressed some underlying primary emotions early in the process and became more comfortable doing so as sessions progressed. The revealing of underlying vulnerabilities helped to soften their stances toward each other and move from a blaming or defending interactional position to a more open one. With the therapist’s gentle exploration, the primary emotions they revealed were often connected to their families of origin.

Phil expressed a primary emotion of shame – related to his betrayal of Jenny through having an affair – in session 7. This was an adaptive shame, as it came from a healthy regret about hurting her and it differed from his otherwise present sense of being a bad person. The expression of this shame and regret was important to Jenny in the context of the affair and helped her to move toward forgiveness and resolution.

While the aftermath of the affair brought conflict and difficulty to their relationship, some of Phil’s underlying pain pre-dated the affair. His most salient core pain appeared to be a loneliness or sadness, which he felt when Jenny did not show an interest in spending time with him or when she rejected him sexually. This was the topic which appeared to bring the most depth of feeling for Phil and contained his unmet need for closeness and intimacy. He expressed some pain around this in session 10, when, in a letter to Jenny, he named sexual intimacy as the one thing he needed to feel more positive about their relationship.

Phil: (Reading from the letter that was a part of their homework) I would like to feel wanted (laughs) (T: it’s alright) in a sexual intimate way, I would like to feel that there’s a natural physical attraction that doesn’t go away when the stress of day-to-day activities occurs.

Therapist: So, this is the core thing for you right? I mean this feeling of wanting that intimacy.

Phil: Yes. That’s why I wrote it down. (Session 10, min. 41).

Phil went on to describe how hurt he had been when Jenny had rejected him sexually on his birthday, after promising they would have intimate time. This need appeared to be the most important one for Phil. Jenny acknowledged that this was an important way for Phil to feel loved, but it remained difficult for her to feel compassion for him as it seemed to trigger her own vulnerability and global distress.

Jenny’s expression of core pain in relation to the relationship was her insecurity and the pain of not being able to depend on Phil. While the therapist helped Jenny to see that this inner insecurity was a sensitivity she had brought into the relationship, the betrayal of Phil’s affair had made this a highly traumatic and painful topic for her. She expressed repeatedly the need to feel that he would stick around. Her core pain was a fear of being out of control, of not being able to hold her life together. It brought her a secondary sense of overwhelm which was frequently present in sessions. Towards the end of treatment, she began to show some ownership of this fear, and recognition that Phil was trying hard to prove himself to be reliable and committed. Jenny had trouble articulating the unmet need behind her pain – she said she didn’t know what she needed, and at one point said ‘so maybe I’m sort of saying if he’s – if he’d only be somebody he isn’t! Right? I would feel better’. (Session 3, min. 38). She seemed to search for some sense of firmness from him that he would be always available for soothing, but his vows of commitment were never soothing enough.

Jenny also expressed the core pain of feeling inadequate or not accepted by Phil for being too stressed and emotionally unavailable. In relation to this pain, she articulated a need for him to show his ‘emotional’ side – to meet her anger or sense of inadequacy, and not to turn away from her. Phil responded to this with compassion and empathy for Jenny, but also with some assertive boundaries about what she could fairly expect from him. His drawing boundaries appeared to be helpful for Jenny in re-assessing how much of her emotions were her own.

Expression of assertive anger

Both Jenny and Phil increased their expression of assertive anger over the course of therapy. Jenny came into the process with a lot of pent-up secondary anger and contempt arising from her perception that Phil did not want her to discuss her feelings about the affair. The therapist began to help Phil and Jenny recognize that there was an assertive role for her anger about the affair, and that it would benefit them both to allow her to express this in a healthy way rather than suppress it. Over time, her anger became less contemptuous, and they both reported that it had been helpful for her to be able to express it. She particularly expressed assertive anger in session 4, about being silenced by previous therapists’ advice not to discuss the affair, and also for having the choice taken away from her about being in a relationship with someone she could trust. This direct expression of adaptive anger represented a significant change in their interaction.

Possibly the most significant interactional change observed over the course of treatment was Phil’s increased ability to assert himself and challenge Jenny’s version of him and their relationship. In session 1, it was notable that Jenny dominated the conversation and at times was quite dismissive about Phil. He sat passively and allowed her to define the narrative. By session 3, he was beginning to assert his view, but he was still quite reactive and defensive, even with the therapist. In sessions 4 and 5, Phil expressed heartfelt regret for the affair and also recognized that Jenny had the right to express her anger. By the last 4 sessions, Phil was consistently stating his point of view, in a non-blaming, productive manner, while still taking Jenny’s view into account. He told his wife that her worries and demands were draining on him, and that he sometimes got tired of having to manage her. He also told her that she was disrespectful toward him in arguments. In session 9, he pushed back against her attempts to change him: ‘[speaking to the therapist] … with respect to feelings, yeah, I mean she wants me to feel a certain way I can’t feel, you know?’ (Session 9, min. 15). In session 10 again, he was interactionally compassionate and relational, responding directly to her requests but also setting out his own position and disagreeing with some of her framing. The establishment of Phil’s boundaries and standing up to her after years of placating had a transformative effect on their relationship as he met her in a more engaged manner than when he just withdrew. This appeared to reassure Jenny, who listened intently (Session 10, min. 24).

Compassion

In the early sessions, there was little compassion expressed as each partner was stuck in the negative interactional patterns, with justifying their own behavior and reporting the ways they felt criticized or neglected. Any understanding of the partner’s position was expressed in a non-aroused manner and usually followed by an expression of anger or blame. In this atmosphere, neither of them felt safe enough to express vulnerability or compassion for each other. For example, in session 2, Phil looked to Jenny for some acknowledgment that he was feeling underappreciated for taking care of their son for a week, however, he laced his plea with an implicit criticism of Jenny, which she picked up immediately, reacting angrily:

Phil: I would like some acknowledgement of how hard it was for me (T: right right) right? How much you appreciate that… and I would like you, [to say] ‘I want to take him, I haven’t seen him for a week and a half I want to have time with him just me and him reconnect time.’…Then I wouldn’t feel guilty asking for some time off!

Jenny: [Angrily] Did you not get that? Did you not get that?

Phil: I said guilt-free.

The therapist helped to de-escalate in the first few sessions by slowing things down and validating each partner’s pain and frustration, and slowly Phil and Jenny felt safer in revealing their own vulnerabilities and offering compassion to each other. In later sessions, when each revealed their core pain, they were able to experience and express compassion more openly. When Phil expressed heartfelt shame about the affair (session 7), Jenny was able to see that it was genuine, and expressed a compassionate awareness that the discussion brought him pain. With the therapist’s help, she was also able to recognize that Phil’s need for praise came from insecurity and a desire to be appreciated:

Jenny: “I mean I feel…like I can understand him differently like I, the thing about the ego needing to be stroked or always to be told he’s right and doing everything well… is more that he’s actually insecure (T: right) maybe he’s a little bit vulnerable. (T: uh-huh) …I hadn’t thought about it that way.” (Session 6, min. 47).

In session 11, Phil spoke poignantly about how his understanding of Jenny’s sensitivities from her childhood helped him to empathize more and be patient around her difficulties:

Phil: Well just the problems you had, the issues you had growing up and the kind of person you are, so it helps me interact with you - better, and you don’t have the same background as me, and you don’t have the same supports structures as I do, or whatever, so then you’ve got a different perspective on things. (Session 11, min. 34).

Self-soothing

Towards the end of treatment, there were some signs that Phil was learning to self-soothe more effectively, and Jenny was starting to recognize the need to do so rather than always expecting Phil to soothe her. Phil noted that he had been more aware of his reactions in conflicts at home and had tried to respond more consciously. He also mentioned that understanding Jenny’s difficulties with feeling overwhelmed helped him to soothe his sense of rejection when she did not welcome him sexually. He still needed to find a way to embrace himself when he was feeling lonely, and Jenny was not able to respond.

Jenny appeared to struggle still with self-soothing – in later sessions she continued to collapse into global distress while recognizing that there was nothing Phil could do differently to reassure her. She was beginning to recognize that she needed to do some of the soothing for herself, but this was difficult as she appeared not to have the inner caretaker to make this possible. This was probably a combination of her historical attachment patterns and the lingering trauma from Phil’s affair, which had been so devastating to her sense of safety.

Grief

Jenny expressed a form of letting go in session 7 immediately following Phil’s expression of shame and regret for the affair. Phil spoke profoundly and tearfully about wanting to make Jenny feel at peace, and she was able to receive it, but spoke with sadness about letting go of the idea that things would feel the same as before:

Phil: I want to make that feeling for you. So, you feel at ease and at peace (crying).

Jenny: I know you do, but I think we both have to be realistic that it may never be quite the way we both want it (crying)… I trusted you completely and…I just don’t know if I’ll get there ever again… but it can get better though (sigh) I feel that we’re healing and that our relationship is healing… (Session 7, min. 20).

It was notable that Jenny spoke of them together here, rather than speaking just about herself. There was a joint vulnerability as they were both highly emotionally aroused, and she was speaking from an interactionally relational and collaborative position, rather than blaming him for the situation they were in.

Agency

Phil and Jenny showed some tentative signs of reaching a state of agency and empowerment by the end of therapy. Phil expressed more confidence about being able to resolve their issues and move forward constructively. He spoke about feeling that he had an improved understanding of Jenny’s perspective, but also that he now understood himself better in some ways. In session 11, he explained some of his new perspective as an outcome of therapy:

Phil: … I realised that a lot of cases I just act on how I feel at the moment, you know? (T: yes, yes) …Um, for example, Jenny’s upset, you know, for me the feeling’s ’oh, I’ve got to make her happy’ as opposed to ’I’m upset too’ you know, I mean I’ve…I’ve got to deal with my being upset…before I can help her being upset…it’s also made me appreciate her more as a person. (Session 11, min. 33).

Jenny appeared to feel more ambivalent about moving forward. When distressed, she defaulted to a place of hopelessness and an idea that they were incompatible at their core. While she found it hard to contain her worry about the ongoing difficulties in their relationship, Jenny reported in the final sessions that she felt they had made significant progress on the road to forgiveness.

Discussion

Broadly, the findings in this case study add to the body of research evidence supporting the theoretical frameworks of both EFT for individuals and EFT-C, in terms of theoretical underpinnings and the process of emotional transformation. We observed the presence of primary and secondary emotions in both partners and the negative interactional cycle in which they were stuck. We also observed, as sessions progressed, that both partners became more comfortable with disclosing their underlying vulnerabilities and learned how to respond to each other with compassion. They moved from their original negative cycles of complain-placate and pursue-distance, through disclosing their underlying core pain, their needs, and expressing healthy anger, to reach a compassionate and more productive interactional dynamic which included a partial letting go of the past.

It was observed that the emotional and interactional transformations which took place over the 11 sessions were not linear or consistent. Although both partners became more comfortable revealing their underlying vulnerabilities and softening their stances toward each other, it was observed that they often slipped back into the previously established patterns of blaming, reacting angrily and feeling hurt or abandoned. Pascual Leone (Citation2009) has described clients in individual therapy in good outcome events as progressing in a sawtooth pattern, in a two-steps-forward-one-step-back manner. The detailed observations support the suggestion that progress in EFT-C can sometimes appear chaotic or like a game of snakes (chutes) and ladders (Pascual Leone, Citation2009). These patterns may have continued after the end of therapy and somehow led to the drop in positive outcomes in the follow-up period (an alternative explanation may also be that the short-term nature of the therapy did not allow for enough consolidation of changes).

Jenny’s sequence of emotional processing and relating was particularly noted to be non-linear. She continued to lapse regularly into global distress and an interactional position of blaming or attacking. This was particularly striking at times of vulnerability, where she would express a primary emotion of fear (insecurity) or shame (inadequacy), and then almost instantly revert to a secondary process of attacking Phil by reporting yet another example of why he was unsafe. The need to soften the blamer is an important piece of restructuring the negative interaction, and one of the most challenging therapeutic tasks in EFT (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008; Johnson & Talitman, Citation1997).

There are a couple of possible explanations for Jenny’s swings from vulnerability to attacking and back again. One is the trauma of Phil’s affair, which may have left such a wound that it colored every interaction for her. A similar emotional pattern is described by Johnson et al. (Citation2001) in relation to therapeutic impasses with couples who have experienced attachment injuries (the timing of Phil’s affair during Jenny’s pregnancy may have aggravated the injury). It has also been described as post-traumatic stress, where the injured partner remains hypervigilant and swears never to let themselves be hurt again (Gordon et al., Citation2005). As this couple were only observed post-affair, it is not possible to know how much their negative interaction was as a result of the affair and how much was previously present, although they both reported that many issues including Jenny’s criticizing behavior predated the affair. Another possibility may have been preexisting attachment or personality style for Jenny. Dominant individuals tend to deflect, avoid or distance themselves from vulnerable emotions (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008). Both factors could have made it harder for Jenny to be able to sit with her vulnerability and resist the urge to blame. Studies in individual EFT (e.g. Dillon et al., Citation2016) have shown that some clients remain vulnerable to this kind of emotional collapse into distress, however in successful cases of individual EFT, the instances of such distress become shorter in duration as therapy progresses (Timulak, Citation2015). Again, this may be one of the possible explanations for the drop in scores in the 3-month follow up (although there may be many other explanations).

As this couple had come into therapy with a history of an emotional injury, Phil’s position as the ‘injurer’ was different to Jenny’s in terms of processing underlying pain. The focus was on allowing a resolution of the injury, and this included Phil expressing a sense of heartfelt shame for what he had done. A study by Woldarsky Meneses and Greenberg (Citation2011; using the same data set that this case was drawn from) found that the expression of shame or empathic distress was a key difference between couples who resolved their emotional injuries and those who did not.

Phil had another primary underlying emotion of loneliness or sadness, usually expressed as a desire for more sex and intimacy. This is consistent with research showing that due to traditional gender restrictions, men are more inclined to express the need for more sex rather than more emotional connection and affection (Greenman et al., Citation2012). The therapy did not focus on resolving this dynamic fully, perhaps due to the limited number of sessions. As noted by Wiebe and Johnson (Citation2016), EFT does not focus much on sexual functioning or intimacy, relying more on the improvement of emotional connection to create a better attachment bond, as research correlates this with improved sexual functioning (Birnbaum et al., Citation2006). The perspective and efficacy of EFT regarding sexual intimacy is an area which would perhaps benefit from more research.

A number of types of negative interaction cycles have been described in EFT-C on the dimensions of affiliation and influence (see Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008; Greenberg & Johnson, Citation1988). Most of the descriptions of these cycles focus on a primary cycle, for example pursue-withdraw or dominate-submit, and how they play out in terms of each partner’s needs and triggers. In this case study, the research team observed two different patterns which could be described as two separate but linked cycles (see ). It appeared that each partner had a mix of two primary emotional vulnerabilities and linked unmet needs.

There are a few potential reasons why Cycle A () was more fully explored than Cycle B (), although the therapist touched on of all the underlying issues. It is probable that Cycle A was more fully explored and resolved because the couple were in therapy following an affair, and the original study focused on emotional injuries. It would therefore be natural to focus more time and attention on the pain of the injured party and the forgiveness and resolution of that significant wound. It is also possible that Cycle A was more apparent because it was driven by Jenny’s more dominant primary emotion, and she was the more dominant partner. She spoke more than Phil throughout sessions and drove the discussions more from her perspective. Lastly, the course of treatment in the research project was limited to maximum 12 sessions (only 11 in this case), so it is possible that more sessions would have allowed a focus on the issues underlying Cycle B. Indeed, it appeared in sessions 10 and 11 that Cycle B was emerging as a more urgent issue. The fact that cycle B was not explored more fully could also be linked to the apparent setback at follow-up.

The possibility of two linked cycles raises some implications from a clinical standpoint. Clearly, the most important consideration is whether both partners feel heard and validated in therapy, and this may be possible by combining the cycles or focusing on each partner’s dominant primary painful emotions. However, focusing on one cycle and neglecting another might lead to missing important primary painful emotions for one or both partners. In the final session of treatment, there is a sense that the issue of intimacy and attachment between Phil and Jenny is still not resolved and needs further exploration. There may be a role for exploring and transforming one cycle first and then treating the other cycle in a more long-term approach.

The case offered interesting observations in relation to expressed anger. Recognising the different types of anger allows the therapist to see when anger should be acknowledged or expressed and when it should be contained or bypassed (Goldman & Greenberg, Citation2013). Jenny and Phil came into therapy with anger on both sides. The skillful interventions of the therapist recognized when this anger needed to be expressed (e.g. Jenny expressing her anger about the hurt and betrayal of Phil’s affair; Phil standing up to Jenny’s criticism and asserting his needs) and when it was necessary to soften the anger and identify a deeper primary emotion (e.g. Jenny’s angry criticism of Phil reflecting a fear and a need for support and protection). Assertive anger in particular was observed to be key to the transformation of interactions. On Jenny’s side, she was able to let go after session 4, when, with the help of the therapist’s coaching and reassurance, she had been able to fully express previously unexpressed assertive anger, and got the validation that Phil needed to learn how to hear some of it.

Phil’s ability to increase his assertive behavior through therapy enabled the transformation of their dynamic, too. In fact, it appeared that Phil’s establishment of healthy boundaries was as significant as his expression of compassion for Jenny’s pain (setting aside his apology about the affair). This anger that informs a partner of a boundary is ultimately reassuring, being easier to deal with than withdrawal or an inauthentic placating (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2008).

Strengths, limitations, and future research

The strengths of this study included the detailed minute-by-minute observations made by the research team, leading to a layered, highly detailed account of what happened with the emotional transformation of each individual and between the couple in this case. In addition, studying the videos included listening carefully to the content but also observing body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice which allowed a more complete analysis of the primary and secondary emotions in the room. This approach goes beyond an in-session conceptualization of the problematic cycle that is formulated by an EFT therapist and offered back to the clients for confirmation and/or adjustment in the session. Although there may be some overlap, the research team was articulating fresh observations going well beyond what was verbalized by the therapist in the session. Furthermore, the research team focused on the observation of emotional and interactional change. While facilitated by the therapist, this kind of transformation is not normally verbalized in the session by the therapist, bar brief mentions at the points of reflection (e.g. toward the end of therapy).

There are several limitations to the study. Firstly, using a theory-led approach raises the possibility of being blind to other theoretical perspectives or events in the therapy which may have been better captured by another theoretical viewpoint. Secondly, this couple was measured as successful based on the post-therapy outcome measures, but the follow-up scores indicated some deterioration which is unexplained. This impacts the evaluation of this therapy as successful. Thirdly, the couple in this study were a white, heterosexual, college-educated couple. Couple research continues to be over-inclusive of white, middle to high-income samples and under-inclusive of sexual minorities (Tseng et al., Citation2021). Not only does this blind the research to particular strengths or difficulties that may be experienced by these groups, but it makes the overall research conclusions skewed toward a certain type of couple. Finally, a case study offers the opportunity to provide detail and color to a theory but is highly specific in its application. Each couple has a highly idiosyncratic way of relating to each other based on their individual attachment styles, personality types, temperament, needs for recognition and family and cultural origins, among other elements. It would be good to study more cases intensively to test the model of emotional and interactional transformation to further refine existing models of couple therapy.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (86.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2023.2204480.

References

- Birnbaum, G. E., Reis, H. T., Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., & Orpaz, A. (2006). When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 929–943. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.929

- Dillon, A., Timulak, L., & Greenberg, L. S. (2016). Transforming core emotional pain in a course of emotion-focused therapy for depression: A case study. Psychotherapy Research, 28(3), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1233364

- Elliott, R., & Timulak, L. (2021). Essential of descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: A generic approach. American Psychological Association.

- Enright, R. D., Rique, J., & Coyle, C. T. (2000). The enright forgiveness inventory (EFI) user’s manual. The International Forgiveness Institute.

- Goldman, R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2013). Working with identity and self-soothing in emotion-focused therapy for couples. Family Process, 52(1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12021

- Gordon, K. C., Baucom, D. H., & Snyder, D. K. (2005). Treating couples recovering from infidelity: An integrative approach. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(11), 1393–1405. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20189

- Greenberg, L. S., & Goldman, R. (2008). Emotion-focused couples therapy: The dynamics of emotion, love and power. American Psychological Association.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Johnson, S. M. (1988). Emotionally focused therapy for couples. Guilford Press.

- Greenberg, L. S., Warwar, S., & Malcolm, W. (2010). Emotion-focused couples therapy and the facilitation of forgiveness. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00185.x

- Greenman, P. S., Faller, G., & Johnson, S. M. (2012). Finding the words: Working with men in emotionally focused therapy (EFT) for couples. In D. S. Shepard & M. Harway (Eds.), Engaging men in couples therapy (pp. 91–116). Routledge.

- Hissa, J., & Timulak, L. (2020). Theoretically informed qualitative psychotherapy research: A primer. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12301

- Johnson, S. M. (2020). The practice of emotionally-focused marital therapy: Creating connection (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Johnson, S. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (1985a). Differential effects of experiential and problem-solving interventions in resolving marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.175

- Johnson, S. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (1985b). Emotionally focused couples therapy: An outcome study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 11(3), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00624.x

- Johnson, S. M., Makinen, J. A., & Millikin, J. W. (2001). Attachment injuries in couple relationships: A new perspective on impasses in couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27(2), 145–155.

- Johnson, S. M., & Talitman, E. (1997). Predictors of success in emotionally-focused marital therapy. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 23(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1997.tb00239.x

- McKinnon, J. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (2013). Revealing underlying vulnerable emotion in couple focused therapy: Impact on session and final outcome. Journal of Family Therapy, 35(3), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12015

- Naaman, S., Pappas, J. D., Makinen, J., Zuccarini, D., & Johnson-Douglas, S. (2005). Treating attachment injured couples with emotionally focused therapy: A case study approach. Psychiatry, 68(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.68.1.55.64183

- Pascual Leone, A. (2009). Dynamic emotional processing in experiential therapy: Two steps forward, one step back. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014488

- Pascual Leone, A., & Greenberg, L. S. (2007). Emotional processing in experiential therapy: Why “the only way out is through. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.875

- Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/350547

- Stiles, W. B. (2007). Theory-building case studies of counselling and psychotherapy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7(2), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140701356742

- Timulak, L. (2015). Transforming emotional pain in psychotherapy: An emotion-focused approach. Routledge.

- Timulak, L., & Pascual Leone, A. (2015). New developments for case conceptualisation in emotion-focused therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1922

- Tseng, C., PettyJohn, M. E., Huerta, P., Miller, D. L., Agundez, J. C., Fang, M., & Wittenborn, A. K. (2021). Representation of diverse populations in couple and family therapy intervention studies: A systematic review of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, and income in the United States from 2014 to 2019. Family Process, 60(2), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12628

- Warwar, S., & Greenberg, L. S. (1999). Client emotional arousal scale-III [ Unpublished manuscript]. York Psychotherapy Research Clinic, York University.

- Welch, T. S., Lachmar, E. M., Leija, S. G., Eastley, T., Blow, A., & Wittenborn, A. K. (2019). Establishing safety in emotionally-focused couple therapy: A single case process study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(4), 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12398

- Wiebe, S. A., & Johnson, S. M. (2016). A review of the research in emotionally-focused therapy for couples. Family Process, 55(3), 390–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12229

- Woldarsky Meneses, C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). The construction of a model of the process of couples’ forgiveness in emotion-focused therapy for couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00234.x

- Woldarsky Meneses, C., & McKinnon, J. M. (2019). Emotion-focused therapy for couples. In L. S. Greenberg & R. N. Goldman (Eds.), Clinical handbook of emotion-focused therapy (pp. 447–469). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000112-020