ABSTRACT

Some aspects of experience can be challenging for research participants to verbalise. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) researchers need to get experience-near to meet their phenomenological commitments, capturing the “texture” and quality of existence, and placing participants in relation to events, objects, others, and the world. Incorporating drawing into IPA designs provides a vehicle through which participants can better explore and communicate their lifeworlds. IPA researchers also require rich accounts to fulfil their interpretative commitments. Drawing taps into multiple sensory registers simultaneously, providing polysemous data, which in turn lends itself to hermeneutic analysis. This article outlines a multimodal method, the relational mapping interview, which was developed to understand the relational context of various forms of distress and disruption. We illustrate how the approach results in richly nuanced visual and verbal accounts of relational experience. Drawing on an “expanded hermeneutic phenomenology,” we suggest how visual data can be analysed within an IPA framework to offer significant experiential insights.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) is concerned with people’s experiences, understandings, and how they find themselves in-the-world. It requires data in the form of “rich, detailed, first-person” accounts of idiographic experience (Smith, Flowers & Larkin Citation2009, p. 56). IPA researchers need to get experience-near to meet their phenomenological commitments whilst also seeking accounts that are rich in expressive content to support more expansive interpretation suitable for IPA’s hermeneutic commitment. In IPA studies, data have predominantly been collected via participants’ verbal accounts, with interviews and diary methods advocated as the most suitable (Smith et al. Citation2009). Yet the fullness of lived experience is not easy to communicate verbally (Boden & Eatough Citation2014), and many aspects of the human predicament can seem beyond words (Todres Citation2007). This is often true of the ambiguous, contradictory, and idiosyncratic aspects of felt-experience, which frequently occur in the prereflective, implicit domain (i.e., taken for granted but fundamentally orient us within our world; Ratcliffe Citation2008). Relational experience, the topic of our enquiry, is fraught with such felt-experience, which could easily elude researchers using only traditional methods of enquiry.

Whilst there are a number of innovative ways to get experience-near within a phenomenological paradigm, in this article we explore why and how researchers might incorporate visual methods into the IPA canon, specifically drawing. Whilst a number of recent phenomenologically oriented articles use drawings (e.g., Attard, Larkin, Boden & Jackson Citation2017; Boden & Eatough Citation2014; Shinebourne & Smith Citation2011), and visual methods are becoming increasingly accepted within qualitative psychology more broadly (see Reavey Citation2012), there has been relatively little exploration of what drawings can add to IPA methodology specifically. This article will describe one example of a drawing-and-talking data collection approach, the relational mapping interview. This was designed to support participants to express and reflect upon the complexity, subtlety, and intensity of their relational experience at times of disruption and distress, as part of a series of projects exploring this theme.

In this article, we draw upon our experience of developing and using this approach in two separate studies: one with international postgraduate students and one with young people after a first episode of psychosis. Although seemingly disparate, both participant groups had recently experienced an event that was likely to have disrupted their relational networks (moving overseas, having an episode of psychosis), and we wanted to explore how participants experienced their relational lives at these times. We draw on examples from these two projects to illustrate how incorporating drawings within an IPA frame can support participants to share hard-to-reach aspects of their lived experience, and how we can use that data within hermeneutic-phenomenological analysis. Ethical approvals were granted for both projects, and all participants gave informed consent. Names are pseudonyms, and some identifying material has been obscured or redacted. We also considered specific ethical issues related to visual material (see Temple & McVittie Citation2005; Wiles et al. Citation2008).

What do we mean by lived experience?

The term lived experience refers to our encounters with everything within our lifeworld — the world as it appears to us and is salient for us. In phenomenological terms, when we refer to experience this way we are attempting to capture that quality of human existence that places us in-relation-to events, objects, others, and the world. In this sense, experience is both perspectival (it has a point of view, which is situated and embodied) and relational (it reaches out and is concerned with the objects of the lifeworld). We each have unique ways of being-in-the-world, but these are framed by a number of universal facets of human existence. These may include embodiment, discourse, sociality, spatiality, selfhood, temporality, our life projects, and mood-as-atmosphere (Ashworth Citation2003). If, as researchers, we only attend to traditional, narrative, and linear forms of enquiry, we may miss some of the subtler aspects of the lifeworld, particularly the embodied, intersubjective, temporal, spatial, and atmospheric aspects which tend be implicit (Fuchs Citation2005; Petitmengin Citation2007; Ratcliffe Citation2008). However, experience does not have to be communicated in a literal, narrative form to be meaningfully understood. Analogy, metaphor, and imagery enable us to express and interpret these aspects of experience (Schneier Citation1989), and participants will draw on both normative (Lakoff & Johnson 1980) and spontaneous metaphors (Svendler Nielsen Citation2009) as they attempt to do this.

IPA methodology encourages participants to describe and reflect on their experience, and several IPA researchers have considered metaphor as a source of rich description and meaning (e.g., Smith Citation2011; Rhodes & Smith 2010). Shinebourne and Smith (2010) argue that metaphor allows us to communicate the nuanced texture of our lives. This is because metaphors are multidimensional (Svendler Nielsen Citation2009) or transmodal (Petitmengin Citation2007), working simultaneously across different sensory registers to summon up a holistic, situated, bodily experience and translate it into a reflective, verbalised account (Stelter Citation2000). In IPA, metaphors can be “gems,” pieces of data that with the right amount of hermeneutic “detective work” can illuminate the whole research endeavour (Smith Citation2011). However, lived experience is always more than we can capture in words (Gendlin Citation2017; Todres Citation2007). In research terms, a focus solely on language, even poetic, metaphorical language, will limit what we can know about the world. Nonlinguistic metaphors and visual imagery may therefore provide an important complementary starting place for researching lived experience within the context of IPA.

Visual imagery as a means of disclosing prereflective experience

Like metaphor, visual images tap into several sensory registers at once and can be rich with meaning (Malchiodi Citation2005). Visual methods can easily be incorporated within a data collection process, and drawing in particular is consonant with IPA principles in that it helps express subjective experience in ways that lend themselves to both phenomenological and hermeneutic analysis. Drawings can do this by circumventing the initial need for language, spontaneously capturing the texture of an experience. This combination of immediacy and flexibility can allow the unsayable to reveal itself (Kirova & Emme Citation2006), and as images have a tangibility and stability that the spoken word does not (Hustvedt 2006); they can provide a shared focus for parallel or subsequent verbal discussion. As with other modes of communication, drawing is not a direct representation of experience. The participant impresses meaning upon the paper through the act of drawing and offers up an expression of the experience for consideration (Schneier Citation1989). In this way, the participant is bodily engaged with his or her tangible lived experience (Malchiodi Citation2005; Merleau-Ponty 1964a/1964). A drawing can therefore be an echo or residue of the subjectivity that created it (Hustvedt 2006; Merleau-Ponty 1964a/1964). In turn, encountering an image as the viewer is also a bodily, sensory, and nonsequential experience (Hustvedt 2006). Thus, like metaphor (Shinebourne & Smith 2010), drawings seem to create a bridge, connecting one person’s embodied experience to another’s, without the immediate need for a verbal translation.

How we use images and image-making within research depends on our epistemological frameworks and research interests (Reavey Citation2012; Rose Citation2001). At the very least, a participant drawing can provide an interesting starting point to elicit verbal data. Visual methods seem to disrupt participants’ rehearsed narratives (Reavey Citation2012), allowing multiplicity to surface more readily. Through drawing, participants also seem encouraged to use the aesthetic qualities of language (Todres & Galvin 2008), trying out words to communicate their fuller experience, for example, by switching to more metaphorical and poetic language. Thus visual methods seem to improve the depth of the verbal data. However, we feel drawings also deserve to be seen as communicative in their own right, standing alongside the verbal account, as a secondary mode through which to interpret the phenomenon directly. A drawing can therefore provide the “thick depiction” that complements the “thick description” gathered in a traditional interview (Kirova & Emme Citation2006, p. 2). Images, like metaphors, are ambiguous, polysemous, and emergent (Dake & Roberts Citation1995; Reavey Citation2012), and this is an advantage for an explicitly interpretative approach, such as IPA.

Visual methods, drawings and IPA

The use of visual methods within IPA research is gaining traction. IPA studies using photo-elicitation (e.g., Silver & Farrants Citation2016), visual voice (e.g., Williamson Citation2018), and found images (e.g., Bacon, McKay, Reynolds & McIntyre Citation2017) are increasingly being published, and there are a number of student theses combining photos, objects, or found images with IPA. There is also a small body of IPA and hermeneutic-phenomenological studies that specifically incorporate the use of drawings. Shinebourne and Smith (Citation2011) appear to be the first to publish an IPA study using drawings with their article about long-term recovery from addiction. They note that rehearsed narratives can be a feature of recovery accounts, and they introduced drawings as a way to potentially disrupt these narratives and gain new insights into the phenomenon. Their article includes analysis of a number of drawings, and they explain how their hermeneutic process was grounded in the participants’ own interpretations and was derived through an iterative analytic method of moving between the verbal and visual. Boden and Eatough (Citation2014) develop these ideas in their methodological article, which describes a multimodal approach involving embodied, poetic/metaphoric, reflective, and visual data, which they illustrate with a case-example on relational guilt. They provide two frameworks to assist in analysing drawings from a hermeneutic-phenomenological perspective: one focusing on how the drawing is produced and one on what is produced.

Nizza, Smith and Kirkham (2017; pain and identity) and Attard et al. (2017; psychosis and adaptability) cite elements of the Boden and Eatough (Citation2014) approach. The Nizza et al. (Citation2017) study further progresses the methodology by including drawings within a longitudinal design, analysing six drawings completed over three interviews. Kirkham, Smith and Havsteen-Franklin’s (Citation2015) article, also on pain, cites the Shinebourne and Smith approach, describing how they analysed the drawings for “style, tone, colour and content” (p. 400) alongside the verbal data. Developing the IPA notion of the “double-hermeneutic” (Smith et al. Citation2009), they suggest including drawings results in a “triple hermeneutic” (p. 400), linking the sense-making of both researcher and participant with the participant’s imagery and lived experience.

Unlike qualitative research more broadly, the articles in this small corpus seem to share an understanding that drawings contribute data in their own right, that they support participants to engage with a phenomenon anew, and that drawings should only be understood in relation to the participants’ own meaning-making (as opposed to making interpretations based on pre-existing meanings via symbols, archetypes, and so on). Each article describes broadly similar adaptations of IPA to develop an analytic process of iteratively moving between image and verbal account. However, the degree to which the analytic engagement with the drawings is reflected in the published findings varies and may be due to differences in focus, method, or publication choice. The articles seem to vary more in terms of how the data are collected. Both the Kirkham et al. (Citation2015) and Nizza et al. (Citation2017) studies describe leaving their participants to produce the drawings privately, whereas the Boden and Eatough (Citation2014) approach argues that how the picture is produced can be as informative as what is produced, so they recommend observing the participant and writing reflexive notes on the process. There also seem to be differences in how the invitation to draw is given to participants. These include the type of image to be produced (e.g., abstract, no specification), the prompts provided (turning attention towards the body, remembering a specific experience, focusing on present self-experience, focusing on meaning-making), and how instructions or prompts are given (verbally, guided, written-down). However, they all seem to draw attention to how the drawings enhanced the research, providing rich, evocative data in themselves and encouraging insightful metaphoric verbal accounts.

Capturing relational experience through drawings

In our work on disrupted relational experience, we are interested in understanding what it is like and what it means to be connected with others at times of distress and instability, primarily because connectedness has been shown to be so fundamental to our psychological and physical wellbeing (e.g., Baumeister & Leary Citation1995). Sociality and intersubjective experience is a key feature of the lifeworld, but traditional one-to-one interviews tend to favour more individualistic and internalistic accounts. Whilst there is plenty of quantitatively oriented research examining the structure and size of people’s relational networks (e.g., using social network analysis or sociomapping to produce visual diagrams picturing quantitative data sets), much less is known about the subjective quality and texture of people’s relational experiences, particularly at times of distress and disruption. Qualitatively oriented methods for tapping into this aspect of lived experience are needed.

Relational experience lends itself particularly well to visual-spatial representations, and practitioners and researchers in the fields of psychology and sociology have long used diagrammatic forms to capture the complexity of social relationships. Psychotherapy provides two significant starting points, genograms and sociograms, which both offer systematic ways to capture some “objective” and some “subjective” information about groups. Genograms (Bowen; Jolly, Froom & Rosen Citation1980), which originate from systemic therapy, are a formal and structured way to capture information about a family system. Sociograms (Moreno Citation1951) use spatial and diagrammatic details to capture the relative positioning of an actor compared to the rest of the network, and are used within sociology to explore group relations. Both use standardised imagery and symbols to capture aspects such as gender, relationship status, and so on. Extending these ideas, our goal was to develop a method of supporting participants to map their own relationships without the need for standardisation or the goal of objectivity. This positions the participants as the experts in their own experience (Smith et al. Citation2009), and avoids putting unnecessary constraints on them in terms of how the image should be produced.

The relational mapping interview

Whilst IPA guidance often suggests using a semi-structured interview schedule (Smith et al. Citation2009), the relational mapping interview approach uses an “interview arc” and the format of “draw-talk-draw-talk” to structure the interview encounter.

The interview arc

Semi-structured interviews are often organised with awareness of issues such as the sensitivity of the questions, the temporal structure, or funnelling from the general to the particular (Smith et al. Citation2009). The “interview arc” approach extends this idea by structuring the interview around touchpoints that help guide the participant through a journey, in the same way a novel may follow a narrative arc or a symphony may have a musical arc. Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2009, p. 48) argue that a phenomenological interview should involve “wandering together with” the participant, and this approach draws on that ethos. The schedule is less prescriptive than a typical semi-structured interview, with most of the interviewer’s contribution involving spontaneous enquiries into the participant’s emerging image and their verbal responses to the drawing process. The relational mapping interview is structured around four touchpoints: mapping the self, mapping important others, standing back, and considering change. Instead of the standard 10 or so interview questions, there are fewer main questions but many more prompts and probes, and the researcher is even less concerned with sticking to his or her agenda, beyond using the arc as a support to navigate around the four touchpoints.

The draw-talk-draw-talk process

Participant information sheets should be transparent about the request for participants to draw/diagram/map their relational networks. The interview begins with a preamble that should point out a good supply of art materials, remind the participants that their drawing skills are not being judged, and reassure them there are no right or wrong ways to approach the exercise. We found it helpful to informally explore the participants’ relationship to creativity/arts/drawing prior to introducing the task in any detail. However, we encouraged all participants to make use of the materials spontaneously and in whatever way they wished, providing reassurance where needed. We also clarified we would guide them through the mapping process.

The first touchpoint is mapping the self. The initial invitation is for the participant to “represent yourself on the map in any way you wish.” If participants struggled, we would perhaps follow up with, “you can use words, symbols or images – whatever you prefer.” After the participants have finished drawing, the interviewer prompts the participants to say a little bit about what they have done and why. To encourage the participants to flesh out their comments, the interviewer can enquire into position, colour, content, or form by making simple observation statements, which are typically enough to elicit more detail from the participants. For example, “you chose pink”; “you’re sitting on the grass”; “you wrote your name and put a heart around it.” Typically this part of the interview is fairly brief, but what is said here can foreshadow important themes to emerge later. Jake, for example, who was a participant in the psychosis study, drew himself as a cartoon figure with his mouth sewn together. Later, he talked at length about how he cannot share certain aspects of his distress with those around him.

The second touchpoint typically takes most of the time and involves mapping relationships with important others. Participants are invited to start by mapping the relationship that is most important to them. A similar process of stating what you see, prompting, and enquiring follows. This draws on phenomenological principles, for example, curiosity (asking open questions and maintaining a stance of “wonder”; Merleau-Ponty Citation1945/2002), dwelling (being patient with what is unfolding), and bracketing (or better, “bridling” your assumptions so they do not run away with you; Dahlberg Citation2006, p. 16). Our prompts centred around understanding the quality and texture of the relationship, how it was sustained (i.e., activities, interests, means of communication), and how it had been impacted by the participants’ life situations (i.e., moving overseas or experiencing psychosis). This process of draw-talk-draw-talk continues with the participants adding further important people to the map and, with the interviewer’s support, describing those relationships in rich detail. Our participants represented a wide range of relationships, which included friends and family, sometimes professionals, but also pets, the deceased, deities, organisations, and occasionally creative activities (specifically music and art). Some participants used more than one page. It feels important to be open to how participants interpret the task and to be equally curious about each relationship. After mapping the important relationships in the person’s life, the interview can then enquire into other people in the participant’s life. This could include people who are part of the participants’ quotidian social landscape but who may not be well known to them, such as a significant receptionist or teacher. We found some participants did not want to add certain people to the map, and we respected that, asking instead whether they would still like to say something about those connections.

Once the participant has added everyone they wish to include, the interview moves toward the third touchpoint, standing back. This involves a shift from the close, experience-near, idiographic, and phenomenological enquiry into specific relationships to a more reflective, explicitly integrative, and interpretative stance. The participants should be invited to (metaphorically) step back from their picture to take it all in. The drawing process may enable participants to experience themselves differently (Gladding 1992), and the drawing itself can act as an anchor helping participants get some distance and see a new perspective (Malchiodi Citation2005). Compare these two examples:

So what do you think when you look at your picture as a whole?

Yeah, that’s many people actually!

What do you think about there being many people there? You sounded a bit surprised.

Yeah. I didn’t realise before [laughter … counting aloud]. It’s quite a big number and I know that there are many people to trust in and now it’s made me realise even more who is the most important people in my life [laughter].

***

So, when you look at your whole map that you’ve drawn, and just reflect on the whole thing, do you think anything in particular, or feel anything in particular?

Erm, it’s quite funny to see my whole life on, like, on one, one diagram.

Is that how it feels, like your whole life?

Yeah, I feel like it’s my whole life really. There is [faith], uni, friends, family. There’s nothing really else. Yeah, to see all the relationships with everyone. I don’t know, it’s quite… It doesn’t feel like a lot.

This part of the interview allows participants time to interpret and integrate their experience and to make big-picture statements. The interviewer can also surface any specific themes that have seemed important across the interview, but which would benefit from further fleshing out or contextualisation.

The final touchpoint, considering change, explores what has changed in the past, in our case paying particular attention to before and after the disruptive events, and concluding by exploring what changes, if any, participants would like to make in an ideal future. If there is a significant event on the horizon, questions could also explore those changes.

So, in an ideal world, some sort of magical world, would this map look like this or would you change something?

Yeah it would look a bit like this. In an ideal world, these [people] would still be alive. My dad might be on the map if he changed his ways.

Mmhmm, in an ideal world.

Yeah. It’s fine. [pointing to her ex-partner] He’d be way off on the map. [… He’d] just, get out of my head, you know? I still think about him, but like that side of it - that just needs to go.

The ideal future question allows participants to explore how they would like their relational lives to be — their expectations, beliefs, fantasies, and hopes; however, this also brings new information about how things actually are in the present.

Analysis of the drawings: An “expanded hermeneutic phenomenology”

We have argued that the drawing process can elicit rich verbal data, but the images themselves are deserving of analytic attention. Kirova and Emme (Citation2006, p. 22) argue that research “texts” should include any pertinent information, such as verbal, visual, and bodily data, since all are valid forms of meaning and offer sites for interpretation, making the case for an “expanded hermeneutic phenomenology.” In this vein, we suggest a framework () to help guide initial analysis of the visual material. It has been developed from the framework described in Boden and Eatough (Citation2014) for use with abstract drawings. Any analysis of visual material must be consonant with the principles of IPA if it is to be incorporated within an IPA study. Hermeneutic phenomenology is articulated as the process of revealing something that “lies hidden” within the phenomenon yet constitutes its essential nature (Heidegger Citation1962/1927, p. 59). Interpretative “detective work” (Smith et al. Citation2009, p. 35) fully reveals these deeper meanings and can equally apply to visual and verbal material. The interpretative process is a dialectical encounter between what the phenomenon can tell us and what we bring to it (Gadamer 1990/1960) and “is neither fully one’s own, nor is it another’s alone” (Todres & Galvin 2008, p. 571). Thus, we are not suggesting any one “truth” can be revealed through analysis of the drawing. Instead, attention to the image can begin to establish a dialogue between what is said and what is revealed visually, deepening the analysis as a whole.

Box 1. Framework for analysing the relational maps.

Relational mapping interviews: Some examples of their potential

Relational mapping interviews seem to result in exceptionally rich and experientially textured data. We offer three ways in which they can help us grasp complex relational experience, illustrating the diverse ways participants chose to take up the task of mapping their relationships.

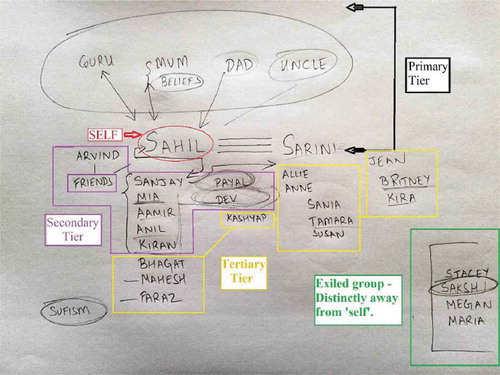

Situating the person in their world: Mapping quickly illustrates complexity and context

Mapping participants’ relational experience provides a way to situate participants within their world. Sahil’s map () is a particularly clear example of how he positions himself within a social hierarchy. It symbolises the value and importance he placed on certain relationships: prioritising his family and spiritual guide above him (the primary tier), his sister at the same level as him, and his friends and other alliances below him, split into two tiers. Those in the tertiary tier had fallen short of the secondary tier in some emotional or practical way. There is also a clear compartmentalisation of his primary relationships (he circles them), which he attributes to their transcendental and enduring nature. Finally, he mentions a group of women, including someone with whom he had had “a fleeting affair.” He speaks about these women disparagingly and seems upset that he could not understand them: “There’s this wall – they’re not letting you in and they are not trying to show their real selves.” This is explored visually by his drawing a box around these names. Unlike the intuitive and spiritual relationships of the encircled primary tier, these interactions have been exiled to the bottom right corner, away from the self and close family and friends, and walled in, perhaps indicating a psychological need for separation and/or fear of contamination.

Figure 1. Sahil’s relational map (international student project) with notation added in colour. This map has been recreated as closely as possible from the original to allow for anonymisation.

The relational mapping interview can allow participants to quickly demonstrate the complexity and intensity of a range of relationships and how they situate themselves within this context. Through speaking about relationships, as they are drawing the participants are engaged in a three-way dialogue about their relational realities, among themselves, the researcher, and the emerging image.

Sense-making in the moment

How and when participants decide to include a particular relationship in a drawing is a fertile source of information about their experience of that relationship. The following two examples demonstrate how drawing can enact relational dynamics and elicit rich verbal data.

Toward the end of his drawing, Jay is deciding whether to add an additional person, Shreya, to his map. Immediately, the ambivalence inherent within his relationship with her becomes obvious, and this choice – whether or not to include her – leads to the following description:

Hmm… Bit of a sticky issue, but then I will add her. She is my girlfriend. For the last, how many years? We’ve been dating, dating is the wrong word - she’ll slap me. Umm… Shreya. So we’ve been with each other for seven and a half years now. I met her when I was in school and I don’t know, we never had this typical inverted-commas-love-story. […] I don’t know what exactly to say about my relationship with her. It’s a bit of a sticky issue. Ok. See if I were to talk about it, it would be like you cannot separate two sides of the same coin. They might not be complementary to each other, but they stick to each other. […] It’s been quite rough, quite rocky. But then, we’ve come a long way actually. Two very identically opposite people, I don’t know how we have stuck together to each other. I don’t even know if it’s going to culminate into something definitive. My family is not very accepting towards it, but then they’ve given me the freedom to do whatever. I have not come to a point in my life where I can actually take a decisive stand on this.

Everything that Jay offers to describe his relationship with Shreya is followed by something that seems to say the opposite, indicating his ambivalence. Jay and Shreya are “identically opposite.” The metaphor of the coin, and the repeated variations on the theme of “sticking,” are insightful: do they stick together, are they stuck together, or are they sticking it out together? It’s a “sticky issue,” irresolvable and awkward. Jay’s family do not accept her yet are liberal about his choice. It is not surprising that he cannot make a “decisive stand”; he is psychologically “stuck.”

Similarly, Jake’s drawing process seemed to help him name aspects of his relational life that were complicated, felt marginal, and/or were not socially sanctioned. In drawing his map, he first added his best friend and then his girlfriend before adding his mother. When reflecting on this later, he noticed:

I find it odd that I kind of, I don’t really confide or trust in her [mother] as much as friends and that kind of bothers me.

Why does it bother you do you think?

Because I thought family was supposed to be the most important thing, I mean that’s the way everyone else sees it. […] It’s kind of- I would see it as offensive if, if she found out about this, she’d find it offensive that I placed her third.

Jake’s concern about the order in which he chose “the most important” people in his life reflects his wider ambivalence about his mother: he says she “keeps me stable” but also that they have “kind of switched roles where I’m like the parent and she’s like the child.”

Similarly, Jake’s decision not to include his father on the map was something he could surface and reflect on. Jake’s account of his relationship with his father also seems contradictory:

Like I didn’t draw anything marking my dad on there, [whispers] cos I don’t trust him at all, no matter what. I can’t believe a word he said. [normal voice] Sometimes I even know he’s lying but I just let him get on with his little stories [whispers] just cos I’m sick of him. [normal voice] I mean I don’t have a bad relationship with him, I don’t, but he sickens me, I wish he wasn’t my father and I know that’s a bad thing to say, I know that is, but…

Jake feels their relationship is not “bad,” but nevertheless he is sick of his father and sickened by him. His switching between a whisper and his normal voice seems to echo the split between his more hidden feelings and more socially sanctioned answers. (“I know that’s a bad thing to say” indicates his awareness of the interviewer’s perspective.) He goes on to describe how his father did not “admit” paternity until Jake was a teenager. Jake’s choice not to include him in his drawing, similar to Sahil’s example above, is indicative of an attempt to exile difficult and painful relationships from the representation. Unlike a genogram or sociogram, there is no attempt here to reach a truthful representation of who is in the network. Our aim is to gain insight into how, psychologically, participants make sense of their relational experience, as it is lived subjectively. With curiosity, those who are and are not included may be discussed, as the participant wishes.

Visual “gems”: Metaphorical imagery

Although many participants chose to map their relationships as a structure, spider-diagram, or list often using words and sometimes with simple decoration, some participants chose symbols or images to represent their relationships. Hari, for example, used the image of a star/sun to represent himself whilst he drew his mother as a swirling universe, indicating their relative power. Karina drew realistic representations of each of her family and friends, positioned together as if posing for a photograph. She added raindrops, butterflies, and musical notes to illustrate the mood and personality of her subjects. Two participants, however, approached the invitation differently. Robert and Aaliya both drew complex, visual metaphors to describe their relational experience as a holistic gestalt. Robert drew an apple tree to represent his family – a family tree – with himself as a fallen apple, ready to be kicked away from the tree, either toward a target or falling into a shark-infested sea, both of which he also illustrated.

Aaliya also chose a botanical theme. She drew herself as a flower (), something “innocent” and vulnerable to the threat of others:

It’s something like that people would usually say ‘oh like it’s quite nice’, but it’s quite like a simple flower, like it can be easily crushed and like I guess some people kind of like, erm, would underestimate it.

Figure 2. Aaliya’s relational map (psychosis project). The word “animal” was added at the very end of the interview. This is an original map.

Next, she added her friends as sun and rain. Aaliya has very little family support but has valued friendships:

They give me like the kind of like support I need, so they’re the sun and the rain, but, like I guess if you get too much sun or too much rain it can also be like negative for a flower. […] Like I can’t always have them around, otherwise it’ll be a bit over-powering, and I guess sometimes they don’t really understand that, or sometimes they’ll like back off too much and I won’t have the support I need.

Next, Aaliya adds the grass and ground.

It’s just going to be the grass, erm…[drawing] maybe the ground beneath that as well and that would probably be my mum, and someone that I kind of like rely on for support and…[pause, looking emotional]

How are you doing? Are you OK? [pause] Is it emotional to think about your mum?

Yeah.

But she’s like the ground underneath you and the grass.

Yeah and I guess, to an extent the grass also needs the sun and the rain, she needs me to be stable for like beauty to grow underneath her and stuff.

Aaliya’s emotionality, her tentativeness about naming her mum (“probably”), and the confusion in her language regarding who is supporting who (“she needs me to be stable”; “beauty to grow underneath her”), and her consideration that her mum (the grass) also needs the support of others (the sun/rain) were indicative of the complex relationship she had with her mother, who also experienced mental health problems.

Toward the end of the interview, when we turned to the fourth touchpoint, “considering change,” Aaliya added the word “animal” next to the flower and drew an arrow:

I would rather be in the food chain or something, the animal eating the flower, rather than the like weak flower being trampled on underneath.

Through Aaliya’s manipulation of her image, she alters her visual narrative to capture her hopes for a more empowered future. Taken as a whole, Aaliya’s drawing indicates the tensions inherent in her relational life, that of being trampled underfoot or being underestimated, the heat of the sun and the drowning rain, being eaten or doing the eating, which seem to encapsulate her psychosocial struggle to recover and to survive. Both Robert’s and Aaliya’s drawings are visual example of Smith’s (Citation2011) “gem.” The images, as simplistic as they may first appear, illuminate not just Robert’s and Aaliya’s experiences but the key relational tensions apparent within the whole psychosis project, specifically the challenge to negotiate intersubjective boundaries.

Conclusions

In our two projects, the relational mapping interview was clearly acceptable to, and engaging for, our participants. At the very least, the incorporation of the mapping activity was complementary and additive to the aims of conventional IPA interviewing, with its capacity for foregrounding the relational context of personal meaning. At times, its contribution far exceeded this, enabling complex and ambivalent experiences to unfold whilst positioning the participants as the experts in their relational lives and allowing them to guide the interview. This revelatory aspect of the relational mapping interview leads us to argue that the use of the draw-talk-draw-talk process, organised around an interview arc, can support participants to find ways to communicate the meaning of their relationship to the world that extend beyond traditional verbalisation.

The multimodal relational mapping interview and the analysis of the drawings from within an “expanded hermeneutic phenomenology” (Kirova & Emme Citation2006) provide researchers with one way of accessing complex relational experience. Incorporating visual methods into IPA can help researchers to get experience-near, meeting IPA’s phenomenological requirements whilst also providing rich, polysemous data to meet its hermeneutic commitments. The embodied and tangible nature of drawing, tapping into multiple sensory registers simultaneously, may explain why it appears to provide such an effective vehicle through which participants can explore aspects of prereflective, idiosyncratic, or hard-to-articulate experiences.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the participants and the two anonymous reviewers. Zoë Boden was supported by a Richard Benjamin Trust award for the psychosis project (“Disrupted Relationships: Psychosis, Connectedness and Emerging Adulthood”). Michael Larkin was supported by a European Research Council Consolidator Grant (“Pragmatic and Epistemic Role of Factually Erroneous Cognitions and Thoughts”; Grant Agreement 616358) for Project PERFECT (PI: Professor Lisa Bortolotti).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zoë Boden

Zoë Boden is Senior Lecturer in the Division of Psychology at London South Bank University. Her research focuses on emotional and relational experience in the context of mental health, using hermeneutic-phenomenological, visual, and embodied methodologies.

Michael Larkin

Michael Larkin is a Reader in Psychology at Aston University. He has a specific interest in phenomenological and experiential approaches to psychology, particularly in qualitative methods. His research involves using these approaches to explore the relational experience and context of anomalous or distressing experiences.

Malvika Iyer

Malvika Iyer is Visiting Lecturer at Newman University, Birmingham, for Statistics and Research Methods and Principles of Psychology. She is interested in using integrative approaches to explore cross-cultural variations in experiences of relational networks and psychological wellbeing.

References

- Ashworth, P 2003, ‘An approach to phenomenological psychology: the contingencies of the lifeworld’, Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 145–56.

- Attard, A, Larkin, M, Boden, Z & Jackson, C 2017, ‘Understanding adaptation to first episode psychosis through the creation of images’, Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, pp. 1–16.

- Bacon, I, McKay, EA, Reynolds, FR & McIntyre, A 2017, ‘“The Lady of Shalott”: insights gained from using visual methods and interviews exploring the lived experience of codependency’, Qualitative Methods in Psychology Bulletin, vol. 23, ISSN (online) 2396-9598.

- Baumeister, RF & Leary, MR 1995, ‘The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation’, Psychological Bulletin, vol. 117, no. 3, p. 497.

- Boden, Z & Eatough, V 2014, ‘Understanding more fully: a multimodal hermeneutic-phenomenological approach’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 160–77.

- Dahlberg, K 2006, ‘The essence of essences–the search for meaning structures in phenomenological analysis of lifeworld phenomena’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 11–9.

- Dake, DM & Roberts, B 1995, ‘The visual analysis of visual metaphor’, Eyes on the future: converging images, 27th annual conference, International Visual Literacy Association, Chicago, Illinois, October 18–22.

- Fuchs, T 2005, ‘Implicit and explicit temporality’, Philosophy, Psychiatry and Psychology, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 195–8.

- Gendlin, ET 2017, A process model. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press

- Heidegger, M 1962, Being and time (J Macquarrie & E Robinson, Trans.). Blackwell, Malden, MA. (Original work published in 1927)

- Hustvedt, S 2005, Mysteries of the rectangle: essays on painting, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

- Jolly, W, Froom, J & Rosen, MG 1980, ‘The genogram’, The Journal of Family Practice, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 251–5.

- Kirkham, JA, Smith, JA & Havsteen-Franklin, D 2015, ‘Painting pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of representations of living with chronic pain’, Health Psychology, vol. 34, pp. 398–406.

- Kirova, A & Emme, M 2006, ‘Using photography as a means of phenomenological seeing: “doing phenomenology” with immigrant children’, Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, vol. 6, Spec. Ed., pp. 1–12.

- Kvale, S & Brinkman, S 2009, InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing, Sage, London.

- Lakoff, G & Johnson, M 2008, Metaphors we live by, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Malchiodi, CA 2005, ‘Expressive therapies: history, theory, and practice’, in CA Malchiodi (ed.), Expressive therapies, The Guildford Press, New York, pp. 1–15.

- Merleau-Ponty, M 1968, The visible and the invisible (A Lingis, Trans. & C Lefort, Ed.), Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL. (Original work published in 1964)

- Merleau-Ponty, M 2002, Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.), Routledge, London. (Original work published in 1945)

- Moreno, JL 1951, Sociometry, experimental method and the science of society, Beacon House, Oxford.

- Nizza, IE, Smith, JA & Kirkham, JA 2017, ‘“Put the illness in a box”: a longitudinal interpretative phenomenological analysis of changes in a sufferer’s pictorial representations of pain following participation in a pain management programme’, British Journal of Pain [Online first], doi:10.1177/2049463717738804

- Petitmengin, C 2007, ‘Towards the source of thoughts: the gestural and transmodal dimension of lived experience’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 54–82.

- Ratcliffe, M 2008, Feelings of being: phenomenology, psychiatry and the sense of reality, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Reavey, P (ed.) 2012, Visual methods in psychology: using and interpreting images in qualitative research, Routledge, London.

- Rose, G 2001, Visual methodologies, Sage, London.

- Schneier, S 1989, ‘The imagery in movement method: a process tool bridging psychotherapeutic and transpersonal inquiry’, in RS Valle & S Halling (eds.), Existential–phenomenological perspectives in psychology: exploring the breadth of human experience, Plenum Press, New York, pp. 311–28.

- Shinebourne, P & Smith, JA 2009, ‘The communicative power of metaphors: an analysis and interpretation of metaphors in accounts of the experience of addiction’, Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, vol. 83, pp. 59–73.

- Shinebourne, P & Smith, JA 2011, ‘“It is just habitual”: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of long-term recovery from addiction’, International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 282–95.

- Silver, J & Farrants, J 2016, ‘“I once stared at myself in the mirror for eleven hours”: exploring mirror gazing in participants with body dysmorphic disorder’, Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 21, no. 11, 2647–57.

- Smith, JA 2011, ‘“We could be diving for pearls”: the value of the “gem” in experiential qualitative psychology’, QMiP Bulletin, vol. 12, pp. 6–18.

- Smith JA, Flowers, P & Larkin, M 2009, Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method, research, Sage, London.

- Stelter, R 2000, ‘The transformation of the body experience into language’, Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, vol. 31, pp. 63–77.

- Svendler Nielsen, C 2009, ‘Children’s embodied voices: approaching children’s experiences through multi-modal interviewing’, Phenomenology and Practice, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 80–93.

- Temple, M & McVittie, M 2005, ‘Ethical and practical issues in using visual methodologies: the legacy of research-originating visual products’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 2, pp. 227–39.

- Todres, L 2007, Embodied enquiry: phenomenological touchstones for research, psychotherapy and spirituality’, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- Wiles, R, Prosser, J, Bagnoli, A, Clark, A, Davies, K, Holland, S & Renold, E 2008, Visual ethics: ethical issues in visual research, ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, viewed on 1 September 2012, eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/421/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-011.pdf

- Williamson, I 2018, ‘“I am everything but myself”: exploring visual voice accounts of single mothers caring for a daughter with Rett syndrome’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, pp. 1–25.