ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the concept and analysis of photographic encounters which we utilised in an interview study to explore experiences of psychotherapy environments. Our study involves a dual perspective design (a sample of therapists, and a sample of clients). Interviews incorporating photographic encounters were transcribed, and then analysed with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Nine therapists and five clients were recruited from a voluntary counselling service in the West Midlands. Two of the therapists first took photographs of the setting. These photographs were used in the study. Interviews involved participants viewing the photographs and then choosing images to discuss. A theoretical framework for analysing the photographic encounters was incorporated alongside IPA analysis. We show how photographic encounters facilitated insights about how participants were experiencing new, layered and embodied engagement with the therapy environment. We argue that photographic encounters in qualitative interviews can foster awareness of tacit experiencing, and that IPA is an effective and complementary approach for working with such data. Our use of photographic encounters contributes to the existing literature on generating multi-modal accounts of experience using visual methods. This paper also offers a distinctive, conceptually-based framework for use alongside IPA to analyse photographic encounters.

Introduction

Photographs are increasingly drawn upon in qualitative research as one amongst several visual methods, such as video walking (Pink Citation2007), video diaries (Pini and Walkerdine Citation2021), drawing (Boden, Larkin & Iyer, Citation2019), community mapping (Duff Citation2012). These methods are used across a range of disciplines such as Psychology (Attard, Larkin, Boden & Jackson, Citation2017; Boden and Eatough Citation2014; Reavey Citation2021; Shinebourne and Smith Citation2011), Social Sciences (Duff Citation2012; Pink Citation2007) and Geography (Emmison and Smith Citation2000). Visual methods are utilised in these research domains to explore areas such as experiences of psychosis (Attard et al., Citation2017), addiction and recovery (Shinebourne and Smith Citation2011), mental health recovery in the community (Duff Citation2012) and experiences of placemaking (Pink Citation2007).

The function and rationale for using photographs in qualitative studies

The function and rationale for using photographs as a visual method varies across empirical studies (Pain Citation2012). Some studies that incorporate photographs do so by using photographs alongside other visual methods and verbal interview data. The function of this is to facilitate rich accounts of experience (Pain Citation2012). A key rationale for the use of photographs also involves epistemological positioning relating to the method and topic (Reavey Citation2021). Phenomenological epistemologies are used in some studies which draw on photographs to explore experience (Pink Citation2009). These approaches incorporate assumptions about ‘lived experience’- that is, how people orient towards the world and how they experience other people, places, objects and occurrences/events (Van Manen Citation1990). Reavey (Citation2021) suggests that lived experience can be reflected across multiple modes and not only via verbal accounts. That is, to understand ‘an experience’ we should consider visual, spatial, embodied and multi-sensory aspects that comprise the nature of everyday experiencing and the meanings we make of them.

The use of photographs in some studies involves drawing upon already existing images (photo-elicitation, Mannay Citation2010; Reavey Citation2021). In other studies, photographs may be created for the study (photo-production, for example, Duff Citation2012). In either case, photographs may offer reesearchers a means of engaging with their participants’ tacit experiences (Pain Citation2012; Reavey Citation2021). Tacit experiences are those which may not have been articulated or recognised. They can be described as areas that may be difficult to explore due to social or psychological barriers (Pain Citation2012) or they may be difficult to put into words, or they may simply be background phenomena which have remained unnoticed. For example, some aspects of experience are implicit due to their familiarity and we do not readily reflect upon them as being a part of our experiencing (Mannay Citation2010). One aspect of implicit experiencing is how we experience the environments we inhabit.

Challenges in capturing experiences of inhabiting environments

Experiences of inhabiting places are often out-of-awareness (Van Manen Citation1990). Inhabiting can be understood as holistically experienced and is considered phenomenologically across different disciplines (Del Busso Citation2021; Merleau-Ponty Merleau-Ponty, Citation[1945] 2004; Tuan Citation1977). To explore experiences of inhabiting is to reach for something that is often implicit. One concept may begin to illustrate this relationship to our environments. Merleau-Ponty, Citation[1945] 2004, 36) refers to a ‘postural schema’ to illustrate how we are not in an environment, but bodily and perceptually inhabiting it. This also means that this ‘inhabiting’ relationship is not about discerning objective points of reference within an environment. It is between our bodies, our situated positioning, and the point of reference which may be our focus, at a given moment. This focus (on an environmental feature, upon ourselves, or upon another person) involves perceptual choices. That is, what we choose to draw towards us by increasing focus, and what then blurs and recedes to the periphery of our attention. This perceptual activity tells us something about how we are experiencing our inhabiting, in a particular moment. This has implications for developing a study design and for drawing forth participants’ accounts of inhabiting therapy spaces.

Our inhabiting is afforded new meaning for us, at each new intersection of temporality and spatiality. We draw upon many layers of previous inhabiting experiences. We gather them up, as we implicitly make sense of occupying and navigating through familiar or new spaces. This means we integrate many bodily, sensory, perceptual, affective and interpretative components into our inhabiting and we may not be consciously aware that we are doing so. Van Manen (Citation1990) describes this as ‘lived space’, a felt and pre-reflective aspect of our existence. Paradoxically then, inhabiting is for each of us a function of a unique constellation of subjectivities, and yet may also be outside of our awareness for much of the time. Using images which evoke some of these subjectivities in their spatial contexts may help qualitative researchers to foreground these experiences for their participants.

The environment and wellbeing

The environment may help or hinder our progress towards wellbeing. This has been explored empirically in the context of psychotherapy environments (Morrey, Larkin, and Rolfe Citation2020; Pressly and Heesacker Citation2001); psychiatric healthcare (McGrath and Reavey Citation2019; Papoulias et al. Citation2014) and physical healthcare environments (Dijkstra, Pieterse, and Pruyn Citation2006). Here, we will focus briefly on psychotherapy environment research: two systematic reviews of psychotherapy environment research (Morrey, Larkin, and Rolfe Citation2020; Pressly and Heesacker Citation2001) highlight research that identifies the environment as a relevant influence in psychological experiencing. Pressly and Heesacker (Citation2001) conclude that physical features may influence psychological and bodily responses in therapy environments (for example, brighter colours may be associated with more positive emotional experiences). Morrey, Larkin, and Rolfe (Citation2020) in their review emphasise the way in which psychological experiencing, which is the purpose for being in the therapy environment, influences the experiencing of that environment. The authors (Citation2020, p.9) develop a therapy environment experiencing model, drawn from the findings in the systematic review, as a way of conceptualising this process as a mereological system. This refers to the way that a person and environment shape each other and together constitute a whole. This experiences of purposive inhabiting within a therapy setting can be helpfully explored in qualitative studies that facilitate the expression of implicit experiences.

Using photographs to facilitate reflection on implicit inhabiting experiences

Visual methods – such as photography – can draw into the foreground the inherently relational and material contexts of our experiences of environments (Reavey Citation2021). Photographs can make familiar environments strange, in order to foster reflection on inhabiting (Mannay Citation2010; Moore et al. Citation2013). One way the use of photographs can disrupt the familiar is through drawing our embodied and inhabiting experiences to the fore (Del Busso Citation2021). This is because taking, using or selecting photographs involves making choices and responding to what is seen. Reavey (Citation2021) suggests that photographs are interpreted, do not contain innate or true meaning and are not neutral. The use of photographs can also create a recollective pause and bring into awareness our movements and positions in spaces (Reavey Citation2021). This can highlight some of the ways we inhabit spaces intentionally.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis and photo-based methods

IPA (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) is a suitable partner for photo-based methods because images do not contain unequivocal meaning, they are interpreted (Reavey Citation2021). IPA similarly gives psychological emphasis to participants’ sense-making.

When using visual methods alongside IPA, Kirkham, Smith, and Havsteen-Franklin (Citation2015, 400) suggest that this facilitates the interpretative process of a “triple hermeneutic. That is, the participant and researcher’s verbal sensemaking and visual data sensemaking are further facilitating exploration of a specific aspect of the participant’s lived experience. The three layers in the interpretative triple hermeneutic process are, firstly, the participant making sense of their experience, secondly, the participant making sense of the visual representation of the environmental space in the photograph, and thirdly, the researcher making sense of the participant’s sensemaking in both of the first two layers of the interpretative endeavour.

The concept of ‘photographic encounters’

We have found it helpful to think of the interviews that utilise photographic data as a ‘Photographic Encounter’, this is aiming to encapsulate the three-dimensional nature of engaging with photographs in qualitative studies. We conceptualise these three dimensions as attuning, enriching and accumulating. Attuning involves purposively reaching for visual expression or resonance, through creating or selecting photographic data. Qualitative accounts are enriched by drawing on photographs and verbal accounts. The co-created research encounter thus involves interpersonal and intrapersonal space for reflection. The third dimension is accumulating – facilitating the simultaneous experiencing of the current, the memoried and the embodied in a ‘newly figural instance’, where all are present together, perhaps for a first time. This may generate a shared sense of ‘atmosphere’ between participant and researcher. The researcher is also making sense of the participant’s photographic encounter and using a ‘critical visuality’ to do so. This photographic encounter concept is best understood through a phenomenological paradigm. The concept of the ‘figural instance’ (a meaning which is crystallised in a moment of visual recognition) is one that we draw on throughout this paper, as a parallel to the more typical unit of the ‘insight’ or ‘meaning’, that might be used when focusing more on verbal semantics.

In the examples in this paper about inhabiting a therapeutic space, we also reflect on the process of the researcher and participant responding to the interview space, the photographs and to each other. The photographic encounter encompasses the holistic nature of this process and underlines that this process is three-dimensional – a live and layered dynamic, facilitating the exploration of ‘inhabiting the therapy space’ as a topic.

Our aims in this paper are, firstly to report and reflect on the use of photographic encounters as a method that can be incorporated into IPA research, and secondly, to show how in our study of therapy environments, these encounters helped to foreground participants’ tacit experiences of that environment. The former has implications for multi-modal methods in IPA research. The latter has implications for how and where we provide psychological therapies.

Method

Study design

The study involved a dual perspective design (a sample of therapists, and a sample of clients). Both samples took part in a photographic encounter interview. An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) photo-production based approach was adopted for this study. The combination of IPA with photo-production based interviews facilitated ‘photographic encounters’ for participants and the researcher during the interview process. The IPA approach emphasises persons as bodily and psychological beings who encounter the world, and the objects which constitute it. People make sense of these encounters, and their relationships to them, as experiences. There are three key conceptual perspectives in IPA: phenomenology, (the focus on what a specific lived experience is like), hermeneutics, (the focus on interpretation – how the researcher is making sense of the participant making sense of their own experience), and idiography (a focus on the particular – this person’s experience of this phenomenon). Together, these provide a complementary, multi-dimensional way of exploring individuals’experiencing. IPA is combined with a way of viewing photographs that has a ‘critical visuality’ (Reavey, Citation2011, p.4). IPA is a suitable partner for this process because psychological emphasis is given to participants’ meaning making about the photographic selections and about their experiences of the therapy environment and the researcher is making sense of the participant’s explorations of this sensemaking. This is the ‘triple hermeneutic’ that Kirkham, Smith, and Havsteen-Franklin (Citation2015, 400) refer to in relation to using drawings alongside IPA and it is equally relevant in the context of selecting and interpreting photographs.

Ethical review

The Research Study Proposal was reviewed by the National Health Service Health Research Authority. The NRES Committee West Midlands – Coventry and Warwickshire. The Committee granted ethical approval for the study on 6 March 2014.

Sampling and recruitment

Participants

We used purposive sampling to recruit nine therapists and five client participants from Oak Tree Counselling Centre (pseudonym) which is a voluntary sector counselling service in the West Midlands. Both therapist and client participants were recruited in this dual perspective design because the focus of the study was on the experiences of inhabiting the environment for those giving and receiving therapy. Each participant group (therapists, clients) was considered and analysed separately using IPA. Therapists were recruited for the interview through email and poster advertisements. Client participants were recruited via communications between the centre manager and therapists. Nine therapist participants took part in the study. Two participants were male and seven were female. Therapist participants were aged between twenty-eight and sixty-three years of age. Participants had been working as therapists at Oak Tree Counselling Centre for between ten months and nine years. Six therapist participants described their therapeutic modality as integrative and three described their approach as Person-Centred.

Five client participants were recruited for the study. One participant was male and four were female. Client participants were aged between thirty-eight and fifty-four years of age. Participants had attended therapy at Oak Tree Counselling Centre for varying lengths of time, this ranged from eight weeks to six months. The length of therapy provision is determined by the manager in conjunction with the therapist and client need. Three participants had received therapy in other organisations previously. Two clients had not received therapy before. Extracts from some of the client and therapist participants are reported here.

Photographers and photographic selections

We chose not to take the photographs at the setting ourselves so that the ‘lens-eye view’ was an ‘insider’ view of the environment (Fetterman Citation2010). Photographing may be experienced as intrusive so the selection of photographers and timing of photographing was considered carefully. The Manager approached two experienced therapists who had worked at the location for several years to take the photographs. These two therapists agreed to take the photographs. The Photo Production and Encounter Process is outlined in . The photographers were given an information sheet about what sort of photographs they might take. Points for consideration included:

Taking general photographs of key spaces as these may be helpful for all participants to consider during interviews. These include: photographs from the doorway of all the therapy rooms, photographs from the therapist chair and the client chair in each therapy room, photographs of all shared staff spaces (including kitchen, administration room, meeting room(s) and all shared client spaces, such as waiting areas and corridors). Photographs outside the building and of entrances/exits outside and within the building.

Considering spaces, objects and layouts in the setting and the different positions from which therapists and clients may view them.

Thinking about the angles from which photographs could be taken – familiar and less familiar as long as they were recognisable.

Taking photographs from close-up, wide angle, further away.

Imagining what is experienced in these spaces. Photographing on the basis of what is seen or what is experienced.

Thinking about photographic choices that can be based on a variety of perspectives, clients, therapists and the photographers’ own personal choices.

Personal choices of photographs may be inspired by a variety of areas such as: level of familiarity with a particular space, routine use of a particular space, objects that seem relevant in particular spaces, understanding of the spaces as a therapist, memories, own experiences.

The first author accompanied the photographers as they took the photographs but was non-directive and answered queries about the photographing, as needed.

Procedure for photographic encounter interviews

An interview schedule was used for the Photo-Production IPA interviews. This included the following questions:

During the interviews photographs of spaces at Oak Tree Counselling centre were displayed on the floor. Photographs were set out randomly. That is they were placed on the floor of the interview room in no particular order, rather than in the order in which the spaces might be inhabited by the participant. The aim was to trouble familiar and potentially unreflected upon visual trajectories and inhabiting. Participants made selections of photographs based on the interview schedule questions, some of these questions and selections also involved selecting captions for the choices made. The first author took photographs of these selections and these were then discussed with participants.

Data transformation and management

Transcription

All photographic encounter interviews were between one hour and one hour and a half hours duration. Due to the large volume of data we used a professional company to transcribe the data verbatim, following a confidentiality agreement.

Data analysis

Interview data – analysis procedures

The primary analysis we present here is the inductive IPA account, but in order to further explore this analysis we present a secondary dialogue with a theoretical framework we also used to analyse the photographic encounter interviews (see ). This framework was used alongside IPA as a complementary theoretical lens through which to analyse the photographic selections and transcripts of the interviews. This framework sits in tandem with IPA analysis as it is clustering questions and concepts that highlight phenomenological aspects of viewing and reflecting on the photographs in the photographic encounters.

The IPA analysis process (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) involved printing and annotating the transcript with notes about descriptive, linguistic and conceptual features within the data. This is alongside emergent themes that may be suggested by clusters of these annotations. We also then used the Theoretical Framework (see ). This framework drew upon questions relating to temporality, spatiality, multi-sensoriality, embodiment, emplacement and researcher reflexivity. Master Tables of multi modal superordinate themes and themes were then developed through a process of abstraction for each participant. This was in line with an IPA focus upon how the researcher is making sense of the participant’s sense-making, about the phenomenon of inhabiting a therapy environment. Relevant photographs and participant responses were also included in each Master Table.

Extracts from results: photographic encounters – a way of exploring dimensions of tacit experiencing

Photographic encounters seem to involve a process that facilitates the participant and researcher to get in touch with tacit experiencing. These can be understood as dimensions of experience. The process of attuning to photographic data through facilitating and making sense of visual resonance, enriching embodied imagining through the shared photographic encounters and accumulating gathered experience. That is, facilitating the simultaneous experiencing of the current, memoried and embodied in a ‘newly figural instance’ where all may be present together.

These dimensions seem to be interconnected so that the focus in the photographic encounter interviews shifts between an exploration of the lived experience of the participant facilitated through selecting and reflecting on photographs and the co-created nature of the photographic encounter where the researcher and participant are both active agents in this process. Extracts from the findings presented here highlight this meta process of attuning, enriching and accumulating which illustrates the utility of photographic encounters.

Attuning to participants’ visual resonance

The process of selecting a photograph, displaying it on a whiteboard and then talking about that selection seemed to elucidate the meanings of visual resonance for participants. Connecting to their resonance participants picked up particular photographs. The photograph seems to facilitate participants to bodily reimagine themselves in the space so that they have the photographer’s eye view of a space and visual trajectory that they are familiar with. From this resonating moment of choosing and reimagining, articulation seemed to unfold about what it is in their experience of inhabiting that space that is resonating. The photographic encounter seems to facilitate explicit exploration of implicit experience.

One good example of this in the study was client participant Colin’s resonance with the photograph of the Counselling Centre reception desk. Colin selected a photograph of the reception desk:

(Ph2_p.34, l.846)

This environmental feature seemed to provide a preparatory tool for him because he had this visual trajectory when he was sitting on a waiting room chair. He explained that the desk helped him to get ready for his therapy session:

… it just reaffirms the order, um, of the place … That- the fact that it’s it’s tidy and it kind of prepares me for the session (Ph2_p.34-35, l.847-850).

Viewing the photograph led Colin to reflect on the process that occurred as he looked at the reception desk, whilst physically waiting for therapy. He reimagined himself on the waiting area chair with the same visual trajectory in the photograph. It was not the desk itself that resonated for Colin. It was his engagement with his own psychological distress as he, simultaneously, gazed towards it. Viewing the photograph led him to articulate this ‘in the moment’ process.

He seemed to interpret the ordered desk that he was now viewing in the photograph in two ways. Firstly, he was implying that it was confirming the orderly nature of the counselling service (‘reaffirming’). Secondly, looking at the tidy desk helped Colin to calm himself and prepare his mind. That is, he recalled that it helped him to psychologically ‘tidy’ or focus his experiencing a little, in preparation for therapy. For example, after selecting the photograph Colin then articulated further the intrapersonal process that the visual trajectory of the tidy reception desk meant for him:

It represents an order … and I think that’s what I’m looking for in my counselling – is order to life to give me some kind of reference points … from the past – and um, into the future … (Ph2_p.30-31, l. 750-759).

Selecting a photograph with a visual trajectory that resonated for Colin in his therapy experience seemed to draw together his lived experience of waiting for therapy, his way of utilising the visual trajectory to ready himself for therapy and his capacity to draw on the photographic representation to elucidate his own symbolic interpretation of its meaning: ‘It represents an order’ (Ph2, p.30, l.750). This seemed to be the process for Colin as he selected and attuned to this embodied visual trajectory in the photograph and reflected on what it meant for him whilst waiting for therapy. The different levels of order that Colin articulated seemed to suggest that this service could provide safe containment and a sense of calm for his, less ordered, psychological experiencing.

Enriching accounts of experience through shared embodied imagining

The co-created encounter between researcher and participant also seemed to involve layered embodied imagining. We are referring here to a phenomenological concept expressed by the visual sociologist Pink (Citation2009, 39), developed in sensory ethnographic work where ‘embodied imagining’ is seen as a situated everyday practice in the context of our material and relational environments. It is more than a visual response and not only a cognitive response. This concept is a useful lens for describing what may be occurring for Laura and the first author at this moment in the interview. It involves imagining how it feels to experience something in an embodied and sensory way. The concept of layering refers to the way that these kinds of ‘feelings towards’ can be elaborated and developed through conversation, such as in the exchange described below.

Layered embodied imagining seemed to enrich the exploration of experience. A good example of this was in two separate explorations of the same photograph selected by therapist participants Laura and Teresa. On top of a bookcase that separates the staff area from the reception area and waiting area in Oak Tree Counselling Centre, there were some items on display. Responses to a photograph of one of these objects facilitated a shared embodied imagining and was evaluated against counselling values.

(Ph2_p.41, l.1008–1011)

The photograph was a close-up of a woolly fireman and a squeezy rugby ball, sitting in a wine cooler. Laura suggested:

It feels like some parts of my house where I’ve put things, I just chuck them in a jug because I don’t know where to put them or I’ll put them somewhere better tomorrow and tomorrow never happens (Ph2_p.41, l.1008-1011).

Here, Laura was indicating that this object evoked a homelike environment, but not the part of the environment that you necessarily have on display for guests. The comment that ‘tomorrow never comes’ was acknowledging the capacity to casually put objects in places, and then cease to ‘see’ them. Not ‘seeing’ them meant that they were not evaluated for any sense of purpose. As Laura and the first author looked at this photograph we both now ‘saw’ the object. The process of selecting the photograph as the first author looked on, then both of us gazing at the photograph seemed to facilitate Laura’s verbal expression about her choice. The photographic close-up, the choice of this photograph and the shared engagement with it, foregrounded the object that was represented. For Laura this seemed to lead her to an embodied imagining, a ‘what is this like’ nature of her experience as she compared it with the placing of what then become ‘forgotten objects’ at home.

The first author, on listening to Laura, felt recognition at this experience drawing on home experience of such objects that cease to be seen. The phrase ‘cobweb corner’ came to mind for the first author. This photographic encounter drew the first author and Laura towards our own embodied imagining. This seemed to be an experience-near moment for Laura and for the first author. We shared the embodied imagining of this moment, drawing on our own experiences and imaginings of the presence of forgotten objects. We both seemed to arrive at this shared perception point as we looked at the photograph and Laura says: ‘It feels like some parts of my house where I’ve put things … tomorrow never happens’ (Ph2_p.41, l. 1008).

What Laura’s response to the photograph also highlighted, was that these objects were actually visible to all in the shared areas of the therapy environment. The photograph showed that this object was on display and that when it was not intentionally focused upon it was still on display but we may not have been noticing it or noticing the messages it might convey. The shared photographic encounter holds the process of ‘seeing’ and ‘not seeing’ the object in tandem. This seemed to facilitate a space for embodied imagining that helped the first author and participant to connect to the experience of ‘seeing’ and ‘not seeing’ this object in this place. Laura also indicated that this photograph was like an absent-minded organisational message, ‘we haven’t noticed that we need to sort this out for you’. As a therapist Laura was interpreting this environmental feature as contradicting the person-centred ethos of the therapy service.

Teresa also selected this photo and chose a caption for it which read – ‘Incongruous’:

(Ph2_p.84, l.1989–1990)

She commented that this was part of ‘the left over from the jumble sale sort of feeling for me’ (Ph2_p.84, l.1990). This time the close-up photo drew a sense of not just a forgotten, but also a discarded object. As the photograph of the object was a close-up, in the first author’s embodied imagining it was like we had walked up to the actual object together and taken a closer look. We were imagining the object in another setting and shared the visual trajectory of a close-up view. Seeing the object afresh in embodied imagining, seemed to really fit the single word caption – ‘Incongruous’. The object evoked thoughts of a different kind of environment where you might see random objects piled together, such as the bric-a-brac stall at a jumble sale. The object and the word together at this point felt shocking. A little like the headline and photograph as they appear together on the front page of a newspaper. Not only made figural, but vigorously declared. This emphasised Teresa’s strength of feeling about the object being out of place. She began to unpack what seemed to be an implicit message about service provision that contradicted her values and organisational values:

… just a really … a really random collection of leftover objects … it’s indicating a lack of … a lack of … a lack of care maybe? This space isn’t really very important (Ph2_p.77, l.1798-1818).

It was like the shared embodied imagining arising from looking at the photograph facilitated connection to a dynamic and passionate engagement with the object and drew out its implicit messages about the therapy space.

Accumulating – reflective processes that lead towards ‘newly figural instances’

This is referring to the way that a photograph can have meaning because it seems to gather reflections on experience in a particular environment that can be both memoried and current. By ‘memoried’ we refer to not one remembered circumstance but a cluster of cumulative memories relating to experiencing the same therapy environment within a session and across therapy sessions, week in and week out.

The visual trajectory seemed to enable some participants to revisit a previous experience with a current gaze and voice. The revisiting seemed to coalesce with the visual trajectory provided in the photographer’s eye view. For some participants this combination illuminated how the environment intertwined with their experience in a way that seemed to take a newly acquired shape in the research interview. Two good examples that illustrated this are client participant Colin’s viewing of a photograph of his therapy room chair and client participant Ann’s selection of three photographs that illustrate the throughflow of light in the therapy centre.

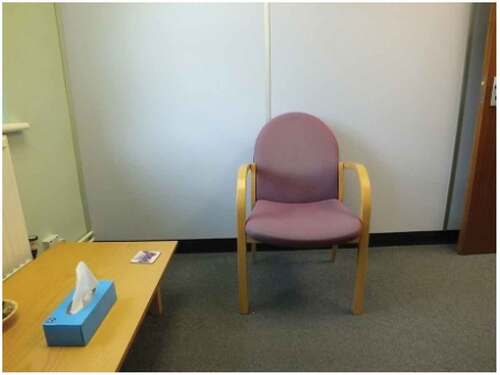

Colin selected a photograph of a therapy room chair for his photo grouping.

(Ph2_p.54, l.350)

The photo was selected because it resonated with the more difficult aspects of Colin’s psychological experiencing in the therapy room. As Colin looked at the photograph, he began to realise it was his therapy room chair. The angle of the photograph, which would be taken from the therapist’s eye view, seemed to lead Colin, not towards the therapist’s perspective, but towards his own emotional experiencing:

It’s only just when I look at it, I think yeah, that is actually this room. The chair I sit in but it, it just … It … I think that – the culmination of the tissues ready to pick up and the chair isolated, it’s not a good feeling for me. It’s not a good … it’s not a good view for me (Ph2_p.53, l.315-321).

It was like Colin was looking at the chair in the photograph, but he was seeing himself. He seemed to be reconnecting to some of his emotional turmoil and feelings of isolation. His repetition of ‘it’s not good’ sounded like a growing and unpleasant emotional reconnection, as he talked about the photograph. This culminated in his comment: ‘I mean that just screams isolation to me’ (Ph2_p.54, l.1350–1351). Colin then explained that isolating himself when he is psychologically struggling is a familiar experience for him:

… because when the … the position I’ve been in the past, isolation is where I go … I do that I take myself away. I go, I go to a very dark place (Ph2_p.55, l.1359-1363).

This then led Colin towards his current psychological experience as he reflected on it during our interview:

I’m in a place at the moment where I don’t - come in bits. I don’t come here (for therapy) in bits. I’m doing ok. I suppose that (photograph) is the opposite of what I want to view from this place (Ph2_p.56, l. 1402-1406).

This photograph of his therapy room chair resonated with Colin and seemed to ‘make visible’ his psychological distress. This may be occurring through merging three perspectives. Firstly, Colin was a viewer of the photograph as the first author accompanied him. Secondly, he also had the therapist’s eye view in the photographic perspective. And finally, he was resituating himself as the person on the chair. This illustrates a signifying moment in the photographic encounter where the photograph prompts Colin to have both a memoried and current experiencing of ‘being in that chair’ during his therapy.

Colin’s reflections on the photograph seem to not just be about the visual orientation of the image but also about his perception of it. The photograph is a representation. It is not his actual therapy room chair, but it is symbolic: the chair representing his psychological dark isolation. It is also cumulatively recollective – it facilitates an experience of his psychological journey that is holistically experienced in his awareness, in this moment, in the interview. In the instant of the encounter with the image Colin is confronted with the depth of this dark place in himself from a place, during the interview, that currently feels ‘ok’. It is a discomforting and rich photographic encounter that makes figural his own dark place and ‘screaming isolation’ from a place in himself that does not now feel that way. Perhaps he is feeling more able psychologically to tolerate difficult feelings, because the therapy is helping him to engage with them. In therapy, one way of describing this according to integrative therapist Ingram (Citation2012, 188) is through the idea of being able to feel the feelings in awareness, not just cognitively describe feelings that were then and there in the past. This may also be an important part of this newly figural instance in the interview.

In a second example of accumulating reflective processes towards a newly figural instance, Ann selected three photographs in sequence to illustrate her experience of light and through flow in the therapy centre.

(Ph2_p.19, l.502–510)

(Ph2_p.19, l.520)

(Ph2_p.19, l.521)

The selection of these three photographs in sequence illustrates how Ann was using the photographs to show movement and throughflow of light, like a storyboard sequence of something that was sensorially experienced and dynamic. One photograph was placed and then the next and then the third so that her movements in selecting and placing the photographs also embodied the throughflow of light. In the first photograph the window was further away and faced the front of the building. The second photograph showed a therapy room window from the doorway. The third photograph was a closer view from the therapy room window. The photographic angles and the choices of these photographs in sequence, seemed to capture the idea of physical movement through the building. It also captured the throughflow of light as this was experienced through the windows as she reimagines physically moving through the therapy centre. There seems to be a progressive movement towards the light, by the third photograph:

… you’re still in contact in a way in what’s going on externally type of thing through the windows and the light and I find that important … as part of my journey and experience … there’s quite a flow, there’s quite a flow through everything … (Ph2_p.19, l.502-510).

A second way in which Ann seemed to accumulate reflective processes is through what the photographs seemed to mean for her in terms of her psychological experiencing. She looked to connect to the external environment. For Ann, the throughflow of light, was also a way of grounding herself in order to manage her psychological experiencing. She described the therapy room layout and lack of stimuli as ‘sterile’ (Ph3_p.40, l.213). The throughflow of light mattered to her. Like the throughflow suggested in her sequencing of photographs, her repetition of ‘there’s quite a flow, there’s quite a flow through everything’ (Ph2_p.19, l.510), seemed to capture this process, involving a sense of fluidity, movement and light flowing from the outside world into the therapy centre and out again.

Ann’s placing of the photographs and her reflection on them seemed to be capturing a newly figural instance where her experience became central rather than tacit through the photographic encounter. Anne was reflecting in the photographic encounter on the then and there meaning of the throughflow of light as she had experienced it during her therapy. She was also showing through her engagement with the photographs and reflection in the research interview the meaning of lightflow for her. In a further layer, Ann also referred in the interview to facilitating her ‘thoughts to flow’ (Ph3_p.5, l.150–151) as she waited for therapy and then moved into the therapy room. These accumulating aspects highlighted a parallel process between lightflow and thoughtflow for Ann.

The concept of a parallel process here (drawn from Doehrman Citation1976) illustrates how a psychological domain might resonate with an environmental one. For example, Ann explained that the need for thoughtflow is about connecting with herself intrapersonally:

… the rooms are fairly sparse so you’re kind of just with yourself and your thoughts and your feelings as opposed to maybe lots of stimuli (Ph 2_p.7, l.197-199).

In a further layer it is also about the co-created therapy process – as an interpersonal flow between therapist and client:

… the connection that that room enables you to have with a counsellor and with your thoughts and feelings … (Ph3_p.42, l.1268-1270).

Ann further illustrates the relevance of ‘natureflow’ and thoughtflow in her comments about her therapy room window and what she can see as she describes the movement of greenery outside the window. Watching the movement of greenery seems facilitate her capacity to articulate her experiencing from thoughtflow to ‘word flow’:

I think the fact that there is some greenery outside and you can kind of see the movement of that can help just the thought process. If you’re taking a few minutes to articulate (Ph2_p.7, l.206-209).

She further highlights the relevance of lightflow and thoughtflow through considering the alternative of not having a window in view:

… and I think the window bit for me is that I like light, I don’t like to be enclosed or feel teemed in and I think that’s more likely to make me kind of close down (Ph2_p.8, l.221-224).

Here, Ann imagined how a lack of opportunity to engage with lightflow or the movement of greenery outside the window may have led to her closing down her capacity to engage in the therapeutic process intrapersonally: ‘kind of close down’ (Ph2_p.8, l.2240). The blended experience of lightflow (and nature flow), thoughtflow (and word flow) seemed to be illustrated in several different ways in the process of selecting, placing and reflecting on the photographs. This seemed to show a current and memoried encounter with the environment of therapy that was accumulative and generated a newly figural instance during the photographic encounter.

Discussion

Photographic encounters seem to offer a three-dimensional approach to reflecting upon lived experience in IPA interviews. This process seems to draw tacit experiencing into the foreground, making it available for reflection. The examples in this paper show how using photographs can draw forth tacit experiencing for reflection and also show that the environment of therapy may be an inextricable part of the therapeutic process, which is drawn upon in different ways by participants. These different ways included Laura’s, Teresa’s and my own embodied imagining in relation to the photograph of the woolly fireman and squeezy rugby ball in a wine cooler which these therapists both experienced as out of place. We also considered Ann’s layered experiences of lightflow and thoughtflow as a way of simultaneously describing her parallel experiences of her therapy and her environment. Colin’s reflections on the ordered reception desk photograph illuminated his way of helping his mind to achieve an order and readiness for his therapy. He also had a surprising experience through selecting a photograph of his therapy room chair which drew to the fore his tacit experiencing of deep isolation earlier in his therapy.

These results show that tacit experiencing of implicit phenomena, such as inhabiting, can be understood more fully through the use of photographic encounters in qualitative interviews. This concurs with Pain’s (Citation2012) results in her literature review suggesting that facilitating expression of tacit experiencing is one of the reasons researchers’ state for incorporating visual methods in study designs. Reavey (Citation2021) highlights how tacit experiencing can be drawn to the fore and explored holistically through gathering multi-modal accounts in qualitative studies via the use of visual methods, such as photographs. This approach recognises that experience is multimodal (visual, spatial, embodied and multi-sensory). Across disciplines such as Psychology (Reavey Citation2021) and Social Anthropology (Pink Citation2009) some qualitative researchers emphasise the relevance of making sense of our multimodal experiencing through utilising visual methods. Such multimodal accounts envelop embodying and inhabiting as part of the holistic, contextual and memoried nature of experience. The extracts drawn from this study highlight these aspects and offer a close-up of the processes that are occurring in the encounters with the photographs.

Using visual methods alongside Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) is a pertinent combination. This is because IPA focuses upon phenomenological accounts of subjective experiencing alongside a psychological emphasis on interpreting participants’ sensemaking. Other papers that use this combination of methods include studies focusing on IPA and drawings (Attard, et al., Citation2017; Boden, Larkin, and Iyer Citation2019; Shinebourne and Smith Citation2011). In these studies getting closer to experiences such as adaptation following first episode psychosis (Attard et al., Citation2017) and idiographic accounts of addiction recovery (Shinebourne and Smith Citation2011) are enriched through the use of drawings. A further rationale for the methodological combination of IPA and drawings concurs with the use of IPA and photographs in this study. That is, focusing on experiences that may be difficult to capture. Boden, Larkin, and Iyer (Citation2019) for example, explore disruptions in relational networks across two different studies. Verbal data, images and mapping data were used in combination to get closer to the lifeworld experiences of participants.

As photographs are understood not to contain innate meaning but subjective interpretations (Reavey Citation2021), IPA is well placed to reflect on the processes involved in sensemaking through its focus on the double hermeneutic (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) and the triple hermeneutic in some IPA studies that utilise drawings (Kirkham, Smith, and Havsteen-Franklin Citation2015). Unlike participant drawings however, photographs are not involving the embodied process of drawing and shaping spatially on paper. Instead photographs are involving a particular focus and engagement with a lens-eye view of something. When participants are the photographers this involves embodied movements. When participants are not the photographer but the viewers of the images, this seems to involve a focus on or troubling of visual trajectories, interpretations and embodied imagining. For example, in Mannay’s (Citation2010) ethnographic paper the researcher draws on photographic data to render the familiar strange for herself and her participants. There is something about the photographic gaze and viewer responses that may have the capacity to illuminate familiar unreflected-upon-experiencing so that it becomes more available for meaning-making. In this study the use of IPA alongside a complementary theoretical framework to analyse the photographic encounters has been fruitful in drawing to the fore some of the constitutive processes that make up inhabiting experiences of the participants.

One area that is distinctive about the use of photographic encounters in this study is the theoretical and conceptual structure used to analyse the photographic encounters about the phenomenon of inhabiting. The theoretical framework used alongside IPA for analysis in this study draws on cross disciplinary phenomenological concepts (embodiment, Merleau-Ponty Merleau-Ponty, Citation[1945] 2004; emplacement, Pink Citation2009; multi-sensoriality, Reavey Citation2021; spatiality, Van Manen Citation1990; temporality, Citation1990) to ask questions of the photographic encounters in the study. The study design and shaping of the semi-structured interview schedules was also theoretically-driven with the photographic encounter interview taking place first, followed by a verbal IPA interview. This was in order to trouble familiar inhabiting trajectories of the therapy setting by clients and therapists in order to experience the environment afresh and draw tacit inhabiting experiences to the foreground (Tuan Citation1977).

There are also potentially important implications when considering the experience of inhabiting an environment, such as a therapy environment, for a specific purpose. For therapists, service managers and policy makers in the counselling and psychotherapy field, the findings in this study indicate that the therapy environment may form part of clients’ psychological experiencing or ways of managing their distress as they attend therapy. For therapists, the environment may also contain features that are experienced as at odds with the purpose of therapy. Features of therapy environments may more, or less helpfully, be an implicit or explicit part of clients’ therapeutic process and therapists’ experience of the environment as matching or hindering its therapeutic purpose. Therefore layout, furnishings, and so forth, can be usefully re-evaluated in different therapy settings because environmental experiencing may be an inherent part of the therapy process. Such reflections may lead to reconsidering the environmental lay-out in cost effective ways which may facilitate the therapeutic process without necessarily fully refurbishing the setting.

Conclusion

Photographic encounters seem to draw into conscious reflection implicit dimensions of experience. The photograph itself is a representation, a tool and a frozen moment that is dynamic when encountered through gaze and interpretation (Reavey Citation2021). We can capture holistic aspects of lived experience through image encounters (Del Busso Citation2021). These dynamic dimensions seem to be shaped by a meta process of attuning, embodied imagining and accumulating during photographic encounter interviews. These findings indicate that this can enrich accounts of experience. Visual trajectories afforded by photographic angles involve a photographer and a choice of photographic gaze. Participants seem to echo or reposition this gaze in their mind’s eye to resonate more closely with their embodied subjective experience. This may elucidate what Reavey (Citation2021, 4) describes as a process of ‘critical visuality’, thus creating a space for tacit experiencing to be seen. These photographic encounters may make figural meanings that are implicit or sensorially experienced in particular spaces. This seems to ‘get under the skin’ of what it is like for participants referred to in this paper to purposively inhabit the therapy environment.

When photographic encounters are used in qualitative studies they may facilitate exploration of tacit and layered dimensions of experiencing. This works well in IPA studies. This may be because the encounters seem to help participants slow down constitutive processes, such as connecting with visual trajectories and embodied imagining. In the examples in this paper this leads towards experience accounts that become more clearly resonant with the participants’ photographic choices.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing experiences of their therapy environments.

Disclosure statement

This research was part of a PhD study funded by the first author. There is no financial interest or benefit that has arisen in relation to this research.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tara Morrey

Tara Morrey is a trained English teacher with experience co-ordinating two middle school English Departments in Worcestershire. She then carried out further training as an Integrative Counsellor. She worked as a counsellor for the NHS in primary care and in the voluntary sector with Women’s Aid. Tara completed a PhD in Psychology at the University of Birmingham in 2018 with supervisors Dr Michael Larkin, Aston University and Dr Alison Rolfe, Newman University. This is exploring clients’ and therapists’ experiences of the therapeutic setting and therapeutic space in psychotherapy. She is interested in qualitative research, particularly interpretative phenomenological analysis, ethnography and visual methods in qualitative research.

Michael Larkin

Michael Larkin is Reader in Psychology, in the Phenomenology of Health and Relationships group. He is a qualitative researcher, whose work often focuses on people’s experiences of psychological distress and psychological services, and in the relational context of coping. He is interested in creative methods and in collaborative and co-design approaches for research and practice.

Alison Rolfe

Alison Rolfe is Head of Counselling & Psychotherapy at Newman University Birmingham, UK. Her main current research interests are in qualitative accounts of clients’ experiences of counselling and psychotherapy. She has previously worked extensively in research in applied psychology, publishing primarily in the areas of addictions, motherhood and sexuality. She also works as an analytical psychotherapist and psychodynamic counsellor in private practice.

References

- Attard, A., M. Larkin, Z. Boden, and C. Jackson. 2017. Understanding adaptation to first episode psychosis through the creation of images. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation in Mental Health 4 (1):73–88. doi:10.1007/s40737-017-0079-8.

- Boden, Z., M. Larkin, and M. Iyer. 2019. Picturing ourselves in the world: Drawings, interpretative phenomenological analysis and the relational mapping interview. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16 (2):218–36. doi:10.1080/14780887.2018.1540679.

- Boden, Z., and V. Eatough. 2014. Understanding more fully: A multimodal hermeneutic approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology 11 (2):160–77. doi:10.1080/14780887.2013.853854.

- Del Busso, L. 2021. Using photographs to explore the embodiment of pleasure in everyday life. In Visual methods in psychology, ed. P. Reavey, 70–82. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dijkstra, K., M. Pieterse, and A. Pruyn. 2006. Physical environmental stimuli that turn healthcare facilities into healing environments through psychologically mediated effects: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 56 (2):166–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03990.x.

- Doehrman, M. 1976. Parallel processes in supervision and psychotherapy. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 40:9–104.

- Duff, C. 2012. Exploring the role of ‘enabling places’ in promoting recovery from mental illness: A qualitative test of a relational model. Health & Place 18 (6):1388–95. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.07.003.

- Emmison, M., and P. Smith. 2000. Researching the visual: Introducing qualitative methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Fetterman, D. M. 2010. Ethnography – Step by step. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ingram, B. 2012. Clinical case formulations – Matching the integrative treatment plan to the client. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Kirkham, J., J. Smith, and D. Havsteen-Franklin. 2015. Painting pain: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of representations of living with chronic pain. Health Psychology 34 (4):398–406. doi:10.1037/hea0000139.

- Boden ,Z., Larkin, M. & Iyer, M. (2019). Picturing ourselves in the world: Drawings, interpretative phenomenological analysis and the relational mapping interview. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16 (2):218–236.

- Mannay, D. 2010. Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research 10 (1):91–111. doi:10.1177/1468794109348684.

- McGrath, L., and P. Reavey, Eds. 2019. The handbook of mental health and space - community and clinical applications. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. [1945] 2004. Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Basic Writings. In ed. T. Baldwin. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Moore, A., B. Carter, A. Hunt, and K. Sheikh. 2013. ‘I am closer to this place’ – Space, place and notions of home in lived experiences of hospice day care. Health & Place 19:151–58. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.11.002.

- Morrey, T., M. Larkin, and A. Rolfe. 2020. What claims are made about clients and therapists’ experiences of psychotherapy environments in empirical research? A systematic mixed-studies review and narrative synthesis. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 20 (4):666–79. doi:10.1002/capr.12336.

- Pain, H. 2012. A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 11 (4):303–19. doi:10.1177/160940691201100401.

- Papoulias, C., E. Csipke, D. Rose, S. McKellar, and T. Wykes. 2014. The psychiatric ward as a therapeutic space: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry 205 (3):171–76. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144873.

- Pini, M., and V. Walkerdine. 2021. Girls on film: Video diaries as ‘autoethnographies’. In Visual methods in psychology, ed. P. Reavey, 187–201. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pink, S. 2007. Walking with video. Visual Studies 22 (3):240–52. doi:10.1080/14725860701657142.

- Pink, S. 2009. Doing sensory ethnography. London: SAGE Publication Ltd.

- Pressly, P., and M. Heesacker. 2001. The physical environment and counselling: A review of theory and research. Journal of Counseling and Development 79 (Spring):148–60. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01954.x.

- Reavey, P., Ed. 2021. Visual methods in psychology – Using and interpreting images in qualitative research. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shinebourne, P., and J. Smith. 2011. Images of addiction and recovery: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of addiction and recovery as expressed in visual images. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 18 (5):313–22.

- Smith, J., P. Flowers, and M. Larkin. 2009. Interpretative phenomenological analysis – Theory, method and research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Tuan, Y. 1977. Space and place – The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

- Van Manen, M. 1990. Researching lived experience. London: The University of Western Ontario.

Appendix

Appendices to be placed in sections indicated in red within the paper

Table(s) with Caption(s) (on individual pages)

Table 1. Theoretical framework for analysing photographic encounters.

Table 2. The photo-production encounter and process.

Table 3. Photo encounter – semi-structured interview schedule.