ABSTRACT

A growing body of work suggests that co-research with older adults contributes to a better understanding of later experienced health and social problems. Yet, few studies have involved minoritised older people as co-researchers, and there has been a lack of critical appraisal of challenges encountered in the process. In response, this paper presents lessons from a project which was aimed at co-producing research to explore experiences of loneliness with and by ethnically and sexually minoritised older people (50+) in Greater Manchester (United Kingdom). The paper presents findings based upon field notes and focus groups with ten older co-researchers reflecting on their motivations,roles, and responsibilities. Four themes will be critically assessed: power and privilege; co-research as an extractive process; co-ownership; and time and financial constraints. At the core of this paper is an examination of how the power held by academics shape opportunities for individuals to meaningfully engage in co-research.

Introduction

Co-research is a participatory method of research that places participants as joint contributors, involving them throughout all stages of the research process from the design through to dissemination of findings. With this approach, the life experiences of participants make them experts and therefore ‘co-researchers’ in the process of gathering and interpreting data (King Citation2000). The term ‘co-research’ is often used as an umbrella term to encompass a family of approaches such as ‘participatory’, ‘emancipatory’, and ‘inclusive’ research (James and Buffel Citation2022), all of which are linked to a set of core principles that emphasise the value of lived experience, collaboration, building on capabilities, creativity, and delivering support and action (Moll et al. Citation2020). One of the main philosophies of co-research methodologies includes promoting the development of equitable and mutually beneficial academic-community collaborations, addressing community socioeconomic inequalities (Felner Citation2020). The popularity of co-research methodologies has recently risen in response to the growing need for more inclusive and responsive policies and services that meet the direct needs of communities (Clarke, Waring, and Timmons Citation2019; James and Buffel Citation2022). Yet there continues to be a lack of clarity around what co-research approaches should involve as well as debates around whether individuals are meaningfully engaged in the process.

Several reviews have evaluated studies involving community citizens as co-researchers. Stoecker (Citation2009), for example, analysed 232 research applications sent to the Sociological Initiatives Foundation that proposed implementing a co-research approach. He found that most proposals emphasised neither participation nor action; most co-researchers were limited to collecting data and were rarely involved at the crucial decision stages of research. Furthermore, the purpose of the majority of the research was to produce papers, presentations, or websites rather than supporting community action. This is in line with Littlechild, Tanner, and Hall (Citation2015) review that found that the most common forms of engagement amongst older people were skewed towards a tokenistic approach. A more recent systematic review that explored how older people had been involved in research also found evidence that studies often keep individuals at the ‘lower end of the participation ladder’, as described by Arnstein (Citation1969, Citation2022). The authors analysed 27 academic papers that involved older people as co-researchers across more than one stage of the research process (James and Buffel Citation2022). The results showed that very few studies reported how co-researchers were involved in developing the study. While most studies included co-researchers in recruitment, data collection, and data analysis, it was often unclear how this was done. In the majority of studies, co-researchers’ involvement appeared to gradually fade when data were being analysed, written up, and disseminated. The authors conclude with four lessons if co-research is to reach its full potential including: developing diversified structures of involvement which allow co-researchers to decide on their level of participation; supporting co-researchers and fostering a culture of trust, openness, and co-learning; embedding principles for improving the rigour of co-research including the need to gather direct perspectives from co-researchers themselves; and ensuring co-ownership of change, including the involvement of co-researchers in evaluating the impact of co-research both in terms of their own experience and the project outcomes.

This paper responds to these recommendations, drawing on a co-research study exploring loneliness among minoritised older people, with the aim of critically reflecting on our practice of co-research to promote mutual learning. In particular, this paper aims to highlight the politics, practice, and consequences of involving minoritised older people in co-research. This is important as people with minoritised identities are largely underrepresented in the co-research literature, yet these populations are most affected by injustice and thereby may benefit the most from being involved in co-research (Ellins and Glasby Citation2016).

The next section will explore how previous studies have used co-research methodologies with minoritised populations and will further highlight how this paper aims to advance knowledge and understanding of using co-research with such groups. This will then be followed by an examination of how a co-research approach was implemented in the study under discussion that investigated the lived experiences of loneliness amongst minoritised older people including an overview of the background of the study, details of the methods, and associated ethical challenges. Next, co-researchers’ critical reflections on being involved in this study will be discussed. Drawing upon focus group data, challenges associated with: power; co-research as an extractive process; co-ownership; and time and financial constraints will be examined. Finally, the authors’ reflections will be discussed in relation to these themes, while providing recommendations for future researchers.

Co-research with minoritised populations

Co-research methodologies aim to prioritise collective decision-making and devolved power, with attempts to empower community citizens and to promote knowledge production within communities (Ward and Barnes Citation2016). Such methodologies are therefore particularly important when working with minoritised populations whose voices are typically neglected in traditional research (Ellins and Glasby Citation2016). Minoritised populations include individuals who are often labelled as ‘vulnerable’, not because of individual characteristics but as a result of social and systemic barriers (Rogers and Lange Citation2013). Minoritised individuals may be discriminated against because of their age, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, and/or socioeconomic status (Gunaratnam Citation2003). A distinctive feature of participatory methods, as described by Haarmans et al. (Citation2022), is the ‘repoliticising of participation where those most affected by injustice are central in both producing knowledge about injustice and implementing solutions.’ Yet minoritised groups are underrepresented in co-research, with only a handful of studies including minoritised individuals as co-researchers (Buffel Citation2018, Citation2019; Ellins and Glasby Citation2016; Tanner Citation2012). This further contributes to the power imbalances that stem from an accumulation of disadvantage across the life course for such groups (Kalathil Citation2013).

One study that amplified the voices of minoritised individuals by including them as co-researchers explored experiences of hospital and discharge process among ethnic minority groups including Asian, Black, and Gyspy/Travellers (Ellins and Glasby Citation2016). They reported that co-researchers were more likely to be able to elicit richer and more nuanced insights from interviewees due to their shared experiences and minoritised identities. However, the authors did not gather direct perspectives from co-researchers or interviewees; instead, the authors assumed what the benefits of involving co-researchers were based on previous research. Buffel (Citation2018, Citation2019), however, did interview co-researchers directly about their experiences of being involved in a research project exploring age-friendly communities. A group of 18 older people (from White British/White Irish/Asian/Black backgrounds) reported that the main benefit of their involvement was their ability to develop trust with interviewees due to shared experiences, as well as having the opportunity to develop new and existing personal skills. The project’s findings benefited the local communities involved as it contributed to the restoration of a much-valued bus service. These findings suggest that co-research has the potential to benefit minoritised individuals and the communities in which they live, suggesting that such methodologies could be used to ensure that services and organisations better meet their needs (Jagosh et al. Citation2012). The next sections of this paper will explore the practice and politics of using a co-research approach in a study which explored the experiences of loneliness amongst minoritised older people.

Co-research in practice

Background of the research study

In response to the opportunities and challenges of an ageing population in Greater Manchester, the Greater Manchester Ageing Hub was set up by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA). The ageing hub brings together partners across Greater Manchester to support and improve the lives of older people across the region. The current research was conducted in partnership with a programme called Ambition for Ageing – which, as a partner of the ageing hub, aimed to tackle social isolation in later life, empowering people to live fulfilling lives as they age.

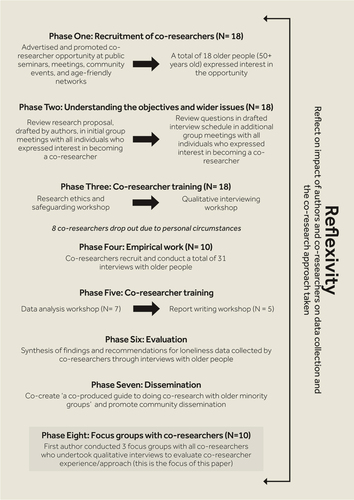

There were three distinct but related parts of the current research (see ): first, a narrative review of the literature on social isolation and loneliness among older people was conducted, highlighting the gaps in the academic literature. Second, a group of older co-researchers was recruited, trained, and supported to develop and refine the research aims and conduct and analyse interviews with older people. The aim of this work was to explore the experiences, drivers, and ways of coping with loneliness amongst minoritised older people. Using an emancipatory framework amplified the voices of minoritised older people involved, providing them with the opportunity to become a co-researcher on a project working to further understand loneliness within marginalised communities. The purpose of this was to promote the participation of groups who may be more vulnerable to loneliness in the design and development of interventions aimed at combatting loneliness (Akhter-Khan and Au Citation2020; Gardiner, Geldenhuys, and Gott Citation2018).

Third, focus groups were conducted with the co-researchers to explore their experiences of being involved in the research while discussing challenges, benefits, and ways of facilitating future involvement. The purpose of this was to interrogate our own practice of co-research, encouraging mutual learning and furthering our understanding of how co-research can be implemented in different populations. The data collected in this phase (Phase Eight in ) are largely used in this paper to form the critical reflections of both co-researchers and authors.

Involving older people as co-researchers

Recruitment of co-researchers

Co-researchers were recruited from established community groups, community meetings, and public seminars using criterion, opportunity, and snowballing sampling techniques. Inclusion criteria were that they had to be aged 50 or over, live in Greater Manchester, and have an interest in conducting research. In line with Greater Manchester’s age-friendly policy frameworks, an older person included anyone aged 50 and over in this study. A recruitment leaflet and poster advertised the opportunity to become a co-researcher in a project examining experiences of loneliness in older age. This advertisement was distributed to community centres, local GP surgeries, and sheltered housing schemes. It was also distributed online via several newsletters through Greater Manchester’s age-friendly networks. Most individuals expressed an interest in the opportunity via email or face-to-face contact. They were then given additional information about the opportunity, an equality and diversity monitoring form, and a contact form requesting their contact details and preferences. This was returned via email or face-to-face meeting. Those who had expressed an interest were then invited to attend the first training session.

Mandatory training for co-researchers prior to conducting interviews

In total, 18 co-researchers completed three mandatory interactive research training sessions prior to conducting interviews. These sessions aimed to enhance and share knowledge between co-researchers about research processes including ethical practice, safeguarding, and qualitative interviewing techniques. The first session encouraged co-researchers to refine the focus of the research and to create an initial interview guide. The narrative review published in the first part of the programme of work was presented to the co-researchers, making them aware of the gaps in the academic literature and allowing them to make decisions on refining the focus of the research. For example, co-researchers jointly decided that the project would focus on loneliness rather than social isolation as the initial proposal had planned. A focus on ethnically and/or sexually minoritised groups was also jointly decided upon and specific research questions were co-created. The second session covered ethical research practice and safeguarding protocols. The final session covered qualitative interviewing techniques including how to listen, probe for further information, and how to approach potentially sensitive topics (see for full training schedule). Co-researchers refined and finalised the interview schedule as a collective three weeks after the first training session.

Table 1. Co-researcher training schedule.

Each session was delivered by the first author at three community centre locations: a centre for Chinese elders, a centre for older South-Asian women, and a general community centre (LGBTQ+ and White British older people attended this session). The groups were trained separately due to the need for translation in the Chinese and South-Asian sessions. Though all co-researchers were fluent English speakers, some preferred to have a translation in their native language to ensure full understanding of written materials. The respective community group coordinator provided oral translations within the sessions. Members of both the Chinese and South-Asian groups volunteered to translate the written materials including the interview schedule, consent forms, and participant information sheets. Community groups were paid for all translation work that was required. Following completion of the three mandatory training sessions, four male and four female co-researchers decided not to participate any further in the research project. This was due to their personal circumstances, health issues, or having other commitments.

Optional training sessions for co-researchers post-interviews

Following best practice, co-researchers were given a choice regarding their level of involvement and engagement (James and Buffel Citation2022). Following data collection, two optional training sessions focusing on data analysis and dissemination were offered to co-researchers. In total, seven out of the ten co-researchers attended the data analysis session and five attended the dissemination workshop. The data analysis session focused on how to use thematic analysis, a method of analysing qualitative data which results in a rich, yet accessible account of the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Co-researchers were taught how to make sense of the data and to report patterns inherent within it, reading and coding a sample of anonymised transcripts. Thematic analysis was used because this is an accessible, flexible, and interactive qualitative analysis technique that allows for a diverse group of older people to be involved (Buffel Citation2018). A dissemination workshop was also held, with co-researchers discussing how the project findings could be presented to the city council, community groups, and the public. This later resulted in a co-produced pamphlet about how researchers can facilitate co-research with minoritised older people.

Co-researchers conducting interviews

Following completion of the mandatory training, the data collection phase of the research project commenced. A final group of ten co-researchers participated in this phase (see for sociodemographic characteristics of co-researchers). Co-researchers were aged between 50 and 79 years old (average = 65 years); seven were female. Co-researchers were from a diverse range of ethnically and sexually minoritised backgrounds, self-identifying as Pakistani (3), White British (3), Chinese (2), Indian (1), and East-African Asian (1). Most were regularly involved in social clubs (9) and lived alone (6). Most reported good health (7), with one person reporting excellent health and two reporting fair health. Most co-researchers’ highest level of education was secondary school (6), with three being university-educated, and one leaving education after completing primary school. Co-researchers were mostly heterosexual (7), with two White British men identifying as gay, and one preferring not to say.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of co-researchers.

The main role of the co-researchers was to each recruit and interview at least two older people aged 50 or over who lived independently (i.e. not in residential care) in Greater Manchester. The exclusion criteria for interviewees were: if the individual was younger than 50 years old, if they lived in a residential care, or if they lived outside of Greater Manchester. The inclusion criteria were intentionally kept rather broad to ensure that all co-researchers were able to find someone to interview. The initial focus was on recruiting older adults who did not regularly attend organised social activities. However, co-researchers decided that this criterion was not appropriate as people could still be lonely despite being socially active. It was therefore agreed that older people who attended social groups could be interviewed, but there would be more of a retrospective focus on the times in their lives when they felt lonely. Co-researchers identified interviewees via their social networks (acquaintances rather than relatives or close friends), with interviews being conducted between January and June 2019. Interviews were semi-structured through the use of a written interview guide that was collaboratively created and refined by the co-researchers. The interview guide was piloted by the co-researchers with three community group co-ordinators. Questions deemed to be too restrictive and/or leading were made clearer and more open-ended; if a co-researcher did not collect information on something they deemed to be important, a new question was added following approval from the rest of the group. The final interview guide contained open questions that covered the individual’s personal background and demographics, community involvement, social relationships, experiences of loneliness, and ways of coping. Co-researchers arranged to collect interviewing materials including an audio-recording device (digital dictaphone) prior to their first interview. One-to-one drop-in sessions were offered throughout the data collection phase to provide co-researchers with the opportunity to reflect on their role and discuss any challenges, as and when necessary. Over half of the co-researchers requested feedback on the first interview they conducted, providing them with an opportunity to reflect on the impact of their role on the data collected, enabling to build their confidence. Co-researchers were reimbursed for travel expenses and received a £10 gift voucher for each interview conducted.

Co-researchers analysing interviews

In total, co-researchers conducted 31 interviews with 18 in English, three in Urdu, four in Punjabi, three in Hindi, one in Cantonese, and two in Mandarin (see for sociodemographic characteristics of interviewees). Interviews were transcribed verbatim after each interview recording was received – though with those interviews conducted in a language other than English, the respective community group coordinator met with the first author and provided oral translations while the translations were typed up. These meetings were organised with the respective community group coordinator, as and when necessary. Transcripts and original interview recordings were checked by professional interpreters for translation accuracy and meaning equivalence.

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of interviewees.

In line with the emancipatory framework used, co-researchers were given the opportunity to analyse the data. This is a novel aspect of the project that many studies involving co-researchers do not fulfil (James and Buffel Citation2022). In total, seven co-researchers analysed purposefully selected samples of data (samples were taken from 60% of the interviews collected given time constraints) using thematic analysis in an interactive workshop. A coding schedule was established collectively and was guided by the research questions. Broad themes around the factors shaping experiences of loneliness (poor health, difficulties accessing health services, discrimination, digital exclusion, poverty, access to public transport, and type of neighbourhood in which an individual lived) and coping strategies (psychological techniques, finding comfort in religion, identity affirmation, volunteering, and obtaining and providing social support) were created. One interview contained solely yes/no responses and was excluded from further analysis (in total, 30 interviews were analysed). A summary of the findings was shared with the co-researchers and interviewees prior to using data for academic publications.

Ethics of involving co-researchers

Ethical approval for this project was granted by the School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Manchester. The project used a form of negotiated consent, prioritising consensus-building around the role of the co-researcher group and the research objectives. Co-researchers agreed on group principles around maintaining confidentiality, trust, respect, anonymity, and empathy throughout and beyond the project. There was a continuous and reflexive engagement with the principle of informed consent; for example, consent was (re)negotiated before, during, and after each stage of research. Information sheets were given to co-researchers and interviewees, and consent forms were signed by both groups; the completed paperwork was then kept in a locked office on the university campus. Identifiable information was removed from transcriptions and pseudonyms were assigned to ensure anonymity of data. As requested by most of the co-researchers, this included the names of co-researchers in order to protect their privacy. Co-researchers/interviewees held the right to withdraw their involvement and/or data at any time.

Critical reflections: Focus groups with co-researchers

The next part of the paper will present four critical reflections from the co-researchers based on their involvement in the project. This information was collected via focus groups conducted with the co-researchers as the participants. The details of those focus groups and the analysis of the data will now be discussed, before moving on to report the reflections that came from those focus groups.

Conducting focus groups with co-researchers as participants

Focus groups were conducted to explore co-researchers’ experiences of being involved with the project, their thoughts on the benefits and challenges they faced during the research process, how they felt about the research process, their involvement, and the responsibilities that they had. The co-researchers also developed recommendations on how to include diverse groups of participants in future co-produced projects. In total, three focus groups were conducted – one for each group of the ten co-researchers who conducted interviews (South-Asian, Chinese, and a LGBTQ+/White British group). The groups were kept separate as they were based in different neighbourhoods and therefore it was difficult to find one venue that could easily be accessed by all individuals; but also, it was considered best to meet separately so that the groups could reflect on particular issues such as racism, homophobia, and classism in a safe shared space. Focus groups were conducted face-to-face in private community centre spaces and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, with a mean duration of 72 minutes. The focus group topic guide was informed by findings from Buffel’s (Citation2018) co-research and was drafted and later refined. It was piloted with three older community group coordinators who were not co-researchers. The guide was then adjusted accordingly. The focus groups were conducted in English, semi-structured, and included open questions such as ‘what challenges did you face as a co-researcher on this project?’ Co-researchers also completed a brief socio-demographic questionnaire. Focus groups were audio-recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis of focus groups with co-researchers as participants

Transcripts of the focus groups with the co-researchers were iteratively and systematically coded and analysed using thematic analysis. Excerpts in the qualitative data were systematically categorised in order to find themes and patterns, while being guided by the following research questions: 1) what factors shaped the co-researchers’ experiences of being involved in this research?; (2) what challenges are associated with co-research with minoritised older people?; and (3) How can researchers facilitate meaningful involvement of minoritised older people in future research? The codes assigned to the excerpts of data were then sorted into broader themes such as ‘issues of power’, ‘challenges around co-ownership’, and ‘limits on time and finances’. The final themes that are included in this article were summarised and sent to the co-researchers for approval via e-mail.

Co-researcher reflections

Co-researchers mostly reported that they had benefited from their involvement through learning new skills, meeting new social connections, and feeling that they had made a difference to their community. They also discussed several benefits they felt their involvement brought to the project too, including gathering more in-depth understandings of loneliness among minoritised older people given that they shared similar backgrounds, identities, and experiences with interviewees. For example, Stuart, a 71-year-old White British man who identified as gay, explained how having a similar life experience to an individual he was interviewing aided his interview performance as he ‘just knew how to approach certain questions’:

‘Being a gay man who was very lonely in the past made me a better interviewer I think as I just knew how to approach certain questions, you know, I could sense which ones I had to be a bit more careful about and move on if they didn’t want to talk about something that made them uncomfortable with me’ [Stuart, Male, 71-years-old, White British]

Another benefit to the project included the ability to amplify voices of more marginalised individuals; for example, individuals who did not speak English or those who were socially isolated. Shakiba, a 50-year-old Pakistani woman, explained how her ability to fluently speak four different languages (Arabic, Urdu, Punjabi, English) enabled us to reach women who did not speak English and therefore gather new knowledge on loneliness within these groups:

‘these women would not be able to speak to you in English, so they would be missed if I couldn’t speak different languages. […] They are important as they do not go out much because of the barrier in language, you see? So we got to tell their stories, instead of just missing them out.’ [Shakiba, Female, 50-years-old, Pakistani]

Other reported benefits included: co-researchers being able to offer different interpretations of findings; co-researchers building trust more easily with interviewees which enabled higher-quality data to be collected; and co-researchers being able to disseminate research findings more easily within the community given their established connections. In terms of the factors that had shaped co-researchers’ involvement, four key themes emerged from the focus group data. The themes critically reflect on issues with: power; co-research as an extractive process; co-ownership; and time and financial constraints. Each of these themes will now be reviewed in turn.

The issue of power

The inherent power held by academic institutions, and therefore researchers, is one of the main barriers to achieving equity in co-research approaches (Malone et al. Citation2006; Minkler Citation2004). Power is multi-dimensional and relates to all stages of the research process; thus, it is a challenge that underlies all subsequent themes in this paper. Our aim as academic researchers was to redistribute the power and overcome the participant to research partner divide. As co-researchers reflected on their involvement in the research process, some demonstrated that they may have felt more like participants rather than equitable research partners. For example, Binita, a 59-year-old Indian woman, referred to the first author who delivered the training sessions as ‘teacher’ and described refining the interview guide as ‘homework’. Whilst it was emphasised that the co-researchers were experts, and had been chosen due to their lived experience, this did not seem to change some co-researchers’ perspectives as they continued to use hierarchical language which suggested that they continued to view themselves as ‘students’. This was a particular challenge when working with co-researchers whose first language was not English as they assumed that the first author was more of an expert than them given that English is her first language. This is demonstrated in the quotes below from two Chinese co-researchers, Tsey and Zhan:

‘You’re born here so you know, it is easy for you, my English needs improving so we follow you [laughs] […] Since being a researcher, you know, I’ve been speaking to so many more people who are not Chinese. […] I feel more comfortable practicing English because of speaking to you and doing training, interviews.’ [Tsey, Female, 67-years-old, Chinese]

‘You taught me so much new words in English, research words. […] you’re the expert in researching!’ [Zhan, Female, 72-years-old, Chinese]

At the same time, however, Tsey referred to herself as ‘being a researcher’, which suggests that she felt more than a participant on the project and identified as a researcher. This suggests that she does feel at least partially responsible for the project, demonstrating that at least some power had been redistributed. Yet it was clear that she internalised an academic/research hierarchal structure when she explained why the Chinese co-researchers did not contribute to refining the interview schedule:

‘you being the lead researcher means you are respected already, and we agreed your ideas sounded great’ [Tsey, Female, 67-years-old, Chinese]

Zhan echoed the point that they did not want to ‘offend’ the first author when asked to review the interview guide despite being encouraged to do so. This internalisation of hierarchy and power is a major challenge to truly collaborative co-research (Grant, Nelson, and Mitchell Citation2008).

On reflection, the way in which the training was carried out may have also reinforced the internalisation of hierarchy. Training sessions, meetings, and one-to-ones were mostly delivered in a traditionally academic format. For example, meetings took place in community centres with PowerPoint slideshows, paper materials, and a dictaphone to record the sessions. Such meetings may be referred to as ‘micro-practices’ of power (Foucault Citation1979), where existing power structures are reproduced. To some extent, the current analysis further reinforces this point, as we (academic researchers) are now reflecting on their (co-researchers’) experiences of being involved in the project.

Power differentials also existed between the co-researchers and interviewees, replicating the more traditional researcher-participant hierarchy. Co-researchers used participatory and inclusive language, for example, calling interviews ‘conversations’ to help build a more equal relationship with the interviewee; yet many co-researchers used an investigative interviewing tone, as well as reading from the interview guide. Co-researchers also required interviewees to read and sign participant information and consent forms, as well as seeking consent to record the conversations with dictaphones. Margaret, the only White British female co-researcher, explains how she felt like a journalist, a profession she had left decades ago:

‘It reminded me of my younger days, you know? I forgot how difficult it was. […] I did tell my interviewees this [that she had to keep the interview on track].’ [Margaret, Female, 79-years-old, White British]

Margaret, here, refers to the people she interviewed as ‘my interviewees’ suggesting she feels she holds some power, responsibility, and ownership over them. A main philosophical principle of co-research, and one of its major reported benefits, is that it should address structural injustice, working towards reducing health and social inequalities; yet in this case, those inequalities may have just been reproduced by making the co-researchers the privileged group and the interviewees the less privileged individuals. Of the ten co-researchers who conducted interviews, eight had participated in research as participants or data collectors before; all but one were regularly socially active within community groups; and, all spoke English fluently. This suggests that the co-researchers began the research as a more privileged group despite their minoritised identities, and their interviewer role in the project may have accentuated this privilege rather than fostering equity.

Co-research as an extractive process?

A main principle of co-research is that the research is collaborative and should empower and benefit local communities (Durose et al. Citation2011). The opposite approach to this is often coined ‘the extraction model of research’, where academics enter marginalised communities to research and feedback to institutions with little input or follow-up from the people they worked with (Markowitz Citation2021). Chambers (Citation2008) describes this as ‘outsiders obtaining information rather than local people gaining and using it’. In this study, local people were recruited as co-researchers with most reporting that they felt that the project was different to previous projects they had been involved in as they believed they were more ‘like equal partners’ than subjects of research. Yet the extent to which the co-researcher’s involvement with the interviewees was empowering is questionable. The role of the co-researchers could be seen as extractive as the interviewees did not appear to benefit from being interviewed. Only co-researchers received gift vouchers and expenses for their participation; though most donated their vouchers to community groups. Frank, a 65-year-old man, donated his to the LGBTQ+ group he attends and expressed how he felt that interviewees should have received an incentive:

‘I think the people we interviewed should have got the vouchers as a thank you. […] It was a nice touch for us, but it didn’t affect my involvement in the project. It’s not like it made me take part. There are groups who need it more, like the one I go to!’[Frank, Male, 65-years-old, White British]

He continued to say he felt like he ‘took the information from them’, which may be indicative of how some co-researchers felt that they were trained to extract data from their communities with little benefit to the interviewees. However, other co-researchers contradicted this viewpoint; for example, Shakiba emphasised the importance of telling others’ stories and how this was one of the most important outcomes of the project:

‘The main benefit for me is the fact we will have made a difference to the people we interviewed by retelling their stories … their own words – they deserve it.’ [Shakiba, Female, 50-years-old, Pakistani]

Shakiba felt that story-telling enabled people, who are not currently included in research and policy, to have a voice and express their own feelings, experiences, and narratives using their own words. Wilmsen (Citation2008) notes that research may be extractive when it is carried out but can later be used to empower communities and provide long-lasting benefits. He uses the example of old ethnographies that now provide benefits to Native American communities who are using them to relearn and revitalise their traditional cultures. In contrast, however, Bermingham, Porter, and Cropper (Citation2007) argue that ultimately, most research with marginalised communities reinforces the ‘stigmatising label of deprivation’ instead of making a beneficial difference to people’s lives.

Albeit, some co-researchers reported that the project had benefited minoritised communities by raising awareness of the importance of acknowledging and tackling loneliness in these groups. Stuart gave an example where he had asked the coordinator of a large LGBTQ+ group in the city centre to host an event focusing on loneliness in older LGBTQ+ people on the weekend. This was because several interviewees had reported that the weekend was when they felt most lonely, as is consistent with other research (Qualter et al. Citation2021):

‘it’s been absolutely fantastic for me. I’ve even asked [LGBTQ+ group coordinator] whether we can do an event at the weekend. I’d love to be involved again in another one [co-research project] […] Honestly, just holding events like this in the gay community, I know will help so many lonely people out there.’ [Stuart, Male, 71-years-old, White British]

In summary, co-researchers reported benefiting both socially and financially (through receipt of expenses/vouchers). Co-researchers also spoke of the potential for the re-telling of interviewees’ lived experiences, as well as demonstrating some tangible community changes (i.e. Stuart hosting a weekend event for lonely older LGBTQ+ people).

Co-ownership or not?

Co-researchers were unable to be involved in the early planning stages of the project as the focus of the study had been predetermined by the academic institution and then advertised as a PhD opportunity. This meant that the main decisions of the research design had been decided in advance, yet once co-researchers had been recruited they were able to further refine and re-design the study aims, focus, and procedures. For example, co-researchers chose to focus on ‘loneliness’ rather than ‘social isolation’ as originally planned given that they felt a focus on subjective experiences was more useful information to collect. They also influenced the focus on people with ethnically or sexually minoritised identities as many of the co-researchers identified as having a minoritised identity themselves and viewed loneliness as an important yet neglected topic within their communities. However, data collection methods and the format of the training sessions were pre-determined and no opportunities to change these methods were given to the co-researchers. Despite this, many co-researchers felt that they were given an appropriate amount of control and that they felt like authentic researchers on a co-designed project. For example, Ibrahim, a 68-year-old man who identified as East-African-Asian, noted:

‘I think we had the right amount of responsibility. I did feel like I was co-researching loneliness with you and the others, yes.’ [Ibrahim, Male, 68-years-old, East-African-Asian]

Other co-researchers stated how they valued the choice to ‘pick and choose’ what parts of the project to be involved with, for example, some co-researchers chose not to partake in the analysis or dissemination stages of the research, as Margaret demonstrates here:

‘I didn’t analyse the interviews. It’s not my thing! I’ll leave that to you and will read it after. It’s not to say I didn’t appreciate the invite though!’ [Margaret, Female, 79-years-old, White British]

As stated by James and Buffel (Citation2022) in their recent systematic review, diversifying co-researcher roles and structures of involvement, as well as being attentive to different contributions that co-researchers feel comfortable making, is vital for enabling participatory methods to reach their full potential.

It could be argued, however, that individuals were given the sense of ownership and control within the context of constraints based on power. Ozer et al. (Citation2013) use the term ‘bounded empowerment’ to describe this. Co-researchers were not able to access data as it was locked in a cabinet within an office on the university campus. Co-researchers were also not given the opportunity to co-author academic publications given that they contributed to the first author’s doctoral thesis. Thus, the extent to which co-researchers could be considered to be ‘co-owners’ of the project is questionable.

Furthermore, although co-researchers stated that they benefited personally from being co-researchers on the project, for example by increasing social networks, learning new skills, and making a difference to their communities; the first author benefited both personally and professionally, by gaining new transferable skills and ultimately achieving a PhD with the data collected. One of the allures of co-research approaches is the opportunity in which community partners and academic researchers equally contribute to and benefit from the research, thus, demonstrating their co-ownership (Felner Citation2020). Yet this research demonstrates the difficulties around assessing equal benefits given that different types of roles reflected different types of benefits. It was not clear whether all co-researchers benefited from being involved in the current study. Sonya seemed unsure of whether she benefited from being a co-researcher:

‘I’m not sure I did learn more about loneliness, which is why I joined at the beginning … hmmm. I helped to tell the lady’s stories for them?’ [Sonya, Female, 65-years-old, Pakistani]

Perhaps individuals’ expectations matching the benefits they received was most important, as Frank comments:

‘I knew what to expect from the beginning, I knew I wasn’t expected to publish a paper with you. I’m not fussed about that. For me it was about giving something back and really making sure that loneliness in my community is, shown awareness of. So people know actually, older gay men can be very lonely and need help.’ [Frank, Male, 65-years-old, White British]

Time and financial constraints

Given that the project was part of an academic dissertation, there were significant time and budgetary constraints that limited how truly collaborative the partnership with the co-researchers could be. Criticism from the co-researchers related to the lack of time or funding secured for the study. The quote from Margaret below demonstrates the time pressures many of the co-researchers felt:

‘I sort of thought we didn’t have enough time to look back at the interviews we did – months had passed and we were acting against a deadline. […] I could have probably done with more time for interviews too – it was a really busy week for me and I’m not sure if I put my all into it to be completely honest with you.’ [Margaret, Female, 79-years-old, White British]

Several other co-researchers also stated that their ideas and performance were bounded by time. Co-researchers were given six weeks to recruit interviewees and conduct interviews and a further eight weeks to analyse data and attend the optional training sessions. This timeframe included translation as and when necessary. When asked if they would do things differently if there was more time, Sonya added:

‘yes, more time is needed. Definitely. On a project looking at loneliness in ethnic minority communities? Of course. I could find ladies who never go out, don’t speak any English and struggle with everything they do. Different strategies could be used … but it was a rush and I couldn’t do that, sorry.’ [Sonya, Female, 65-years-old, Pakistani]

Sonya therefore believes that the short timeframe limited the recruitment strategies she could use, highlighting the academic constraints and pressures that shaped the co-researchers’ involvement.

Furthermore, limited funding was secured for the study given it was a dissertation project and this also impacted the co-researchers’ involvement. To illustrate, Frank suggested that more funding would have helped to build a better co-researcher network, enabling him to feel more like he was a member of a team:

‘I think if you had money to do events for us as co-researchers, and we could invite the people we interviewed too. It would have felt more like a team, yeah. I sort of felt like I was working alone sometimes, and I never met the other groups [of co-researchers]. I just reported back to you, and that was that, if you know what I’m trying to say?’ [Frank, Male, 65-years-old, White British]

It was made clear from the beginning of the project that there were no funds to sustain the project after disseminating the findings. This is not in line with the philosophical principles of co-research that suggest that co-research projects should consider the sustainability of a project. Nonetheless, Stuart’s motivation to run an event in order to highlight the issue of loneliness among older LGBTQ+ individuals may have contributed to temporarily improving the wellbeing of his local community.

Budgetary constraints also meant that co-researchers were not paid for their contributions, and instead received travel expenses and gift vouchers for their participation. As mentioned previously, this highlights the unequal power dynamics and brings into question whether the co-researchers co-owned the project. Past studies have, however, reported practical challenges when paying co-researchers for their contributions. For example, Clark et al. (Citation2009) underestimated the amount of time needed to check individuals’ contributions against their allocated time sheets, as well as managing expectations of both co-researchers and the university financial systems that were not geared up to respond to individuals not accustomed to working within such large systems. McLaughlin (Citation2010) further emphasises the importance of any system of payment and reimbursement being quick and responsive – this is often a challenge within university financial systems. When the co-researchers of this study were asked about how they felt about the travel expenses and gift vouchers they received, most appeared indifferent and no-one considered financial payment as essential to their future involvement. Shakiba elaborated:

‘look, we decided ourselves to take part in this project, didn’t we? So it obviously does not matter to us. There are other reasons for us [to participate] [Shakiba, Female, 50-years-old, Pakistani].

Motivations to participate included a will to learn and develop skills, a personal interest in loneliness research, and wanting to ‘help out’ and make a difference. Although the co-researchers did not expect financial payment for their contributions, the lack of financial resources may have excluded some groups within the older population from participating and therefore may have further contributed to power imbalances, ethical issues, co-ownership, and the potentially extractive nature of the approach that was taken.

Author reflections and recommendations

This article reflects on how a co-research methodology was implemented in a research project exploring experiences of loneliness amongst minoritised older people. In particular, it highlights how the underlying issues of power and privilege held by academic researchers shaped the opportunities for individuals to engage authentically in co-research, attempting to avoid tokenistic involvement. It addresses the paucity of academic research on co-research practice, responding to the call for increased reflection on implementing such methodologies (Amann and Sleigh Citation2021; James and Buffel Citation2022). The current findings suggest that co-research methodologies offer the potential to amplify the voices of minoritised groups, encouraging individuals to make small community changes. However, there were also fundamental challenges that constrained the opportunities that the co-researchers had in this project including issues around: power, co-research as an extractive method, co-ownership, and time and financial constraints. We now share some of our own reflections and recommendations for future researchers.

Negotiating power: engage ‘experts by experience’ as early as possible and for as long as possible

A core challenge of co-research, as discussed previously, relates to the redistribution of power through overcoming the participant-partner divide. Upon reflection, it is clear that power could never be completely shifted to the co-researchers as it is inherent within the academic institution. The use of participatory language had limited effect on redistributing power in practice, with many co-researchers never accepting the ‘partner’ role (e.g. the Chinese co-researchers who declined to amend the interview guide). The same power dynamics as in traditional research appeared to be reproduced but the language used was co-opted to describe the methods. It was even more of a challenge to shift the power to interviewees who were in less privileged positions than the co-researchers themselves. This was likely due to the internalisation of the hierarchical structure; as demonstrated in several previous co-research studies, community citizens may feel that they lack a sense of legitimacy and therefore rely on the guidance of ‘expert’ researchers (Grant, Nelson, and Mitchell Citation2008; Haarmans et al. Citation2022). This can reproduce or perpetuate inequalities – the opposite of what a co-research approach aims to achieve (Parveen et al. Citation2018). However, one co-researcher suggested that the project was simply ‘drawing on everyone’s strengths’ as they perceived the first author to be an ‘expert in research’ and perceived themselves to be an ‘expert in life/by experience’. Instead of perceiving a power imbalance, they viewed themselves as having different but equally important roles as the first author, reflecting the different roles within the team.

It is therefore recommended that future researchers ensure that they recognise the different power structures within co-research teams and discuss these openly with co-researchers. We encourage co-researchers to reflect on their own positions in relation to the academic researchers and other co-researchers, encouraging open discussions on how power imbalances could be disrupted in training sessions. For example, having official research roles titled ‘expert by experience’ could help to reorganise and equalise the academic hierarchy as they could be more involved in the first planning stages of research prior to approval from ethical review boards. It is advised that potential community partners are involved as early as possible and for as long as possible, while researchers should be transparent about any pre-planned procedures to promote more equal power distribution. In order for this to happen, academic researchers must focus on striking a balance between meeting the principles of co-research with commitment to research governance standards, funder expectations, and institutional priorities. Previous research with disabled young people has successfully set up ‘co-researcher collectives’, contesting the traditional elitist ways in which research funding bids are generated by including community members as ‘co-researchers’ at the inception of the research process and thus promoting a shared distribution of responsibility from the outset (Liddiard et al. Citation2019a). The collective is now a funded and integral part of the Research Management Team at the University of Sheffield, demonstrating that it is possible to meaningfully include co-researchers in all stages of research (Liddiard et al. Citation2019b).

More than storytelling: encourage partnership working to improve research impact

Critical participatory action research approaches centre community partners’ contributions and plan for mutually and equitably beneficial outcomes (Torre et al. Citation2012). We reflect upon the complexities of the term ‘equitable beneficial outcomes’; for example, who assesses the value of beneficial outcomes? Can beneficial outcomes ever be equitable? How do we assess the value of these outcomes for different people? In our study, different individuals received different benefits and most importantly, all co-researchers reported that their involvement had met (or exceeded) their initial expectations. Several co-researchers stated that they benefited from being involved in the project, though others seemed unsure whether they had personally benefited. Unfortunately, it is not possible to assess whether interviewees or the co-researchers only involved in the initial training sessions benefited as these data were not collected. What is known is that the project had a beneficial impact within the older LGBTQ+ community, as one co-researcher organised a weekend event focused on increasing awareness around loneliness within the community. The co-researcher since reported that the LGBTQ+ organisation now hosts regular events at the weekends to alleviate loneliness. The findings also had an academic impact, addressing several gaps in knowledge within the research community including creating a co-produced guide on facilitating co-research in minoritised populations (Cotterell et al. Citation2022). This guide was disseminated by the co-researchers to local community organisations to promote the inclusion of older minority groups in research and practice. It is perhaps too early to confirm its impact on Greater Manchester policy, though we argue that there is the potential for this research to make an impact because of the advocacy of academics and the authentic voices of minoritised older people.

We recommend that future researchers unpack what community participation is (and is not), while partnership working to promote tangible community impacts should be encouraged. Involving charities, grassroots organisations, and local governments/authorities would further increase the reach of findings, encouraging larger changes within communities. It would also contribute to providing more opportunities to secure funding and resources to improve the scale of research outputs (INVOLVE Citation2020).

Promote co-ownership: use different forms of recognition

The challenge of co-ownership is strongly tied into previous discussions around power, bounded empowerment, internalisation of academic hierarchies, and extractive processes. Given that the project formed the basis of the first author’s PhD by publications, it was not considered possible for co-researchers to co-author the academic papers. Yet members of the academic supervision team were co-authors, further highlighting the inherent power and internalisation of academic hierarchies. Co-researchers instead were given the opportunity to co-author the ‘grey literature’ – a co-produced guide facilitating co-research with minoritised groups that was disseminated to community organisations and networks (Cotterell et al. Citation2022). Upon reflection, this suggests that the co-researcher’s involvement was bounded and they were not treated as equal partners; they were restricted to the ‘community aspect’ of the project rather than contributing to the academic impact and therefore did not benefit professionally from the work as the academics did. Thus, in future research, we advise that researchers offer different forms of recognition – monetary and non-monetary. This could include fair payments, co-authorship of main publications, or recognising them as official members of the research team as has been done in a small number of previous studies (Ayre, Wallis, and Daniell Citation2018; Minogue et al. Citation2019). There is a need, however, for academic institutions to recognise the value of participatory methodologies and community knowledge in order to make this possible.

Importance of time and resources: plan for the unexpected

Although all research projects are subject to time and financial constraints, this study formed part of a doctoral thesis which meant that both funding and time were especially tight. This clearly impacted the way in which the co-research approach was implemented; for example, further training sessions (beyond the three mandatory and two optional workshops) were not possible due to the limited time and finances. Yet two co-researchers suggested that they would have benefited from having more than one session on qualitative analysis techniques. More time and financial resources would have provided opportunities for co-researchers to be more involved in the decisions around the methods and analysis techniques used. To illustrate, one co-researcher who did not continue with their role after the initial training sessions suggested making a video documentary over conducting semi-structured interviews. Ultimately, the academic institution had the final say in which methods could be used given the time and financial constraints; thus, highlighting that the roles of the academics and co-researchers involved were not equal. These constraints also appeared to impact the co-researchers’ involvement, particularly who they were able to recruit – many recruited individuals known to local organisations or services and therefore missed opportunities to reach more socially isolated individuals. The limited financial resources also meant that only more privileged individuals could volunteer to become a co-researcher as there was no income attached to the role. In line with previous research (Clark et al. Citation2009), we recommend that universities offer flexible and creative administrative arrangements to renumerate co-researchers for their contributions. We also advise that future researchers conduct thorough cost-benefit analyses, forecasting for any potentially unexpected additional costs prior to implementing a co-research approach. Future researchers should carefully plan each stage of research on a timeline, setting realistic goals, and allowing for unexpected delays. The extent of co-researchers’ involvement at each stage should be made clear prior to recruiting individuals. We do recognise the difficulties of planning for unexpected expenses and time delays and therefore we expect that co-research methods will only reach their full potential when used on longer term projects.

Reflect on who is interviewing who: acknowledge how characteristics shape data

It is also important to reflect upon the impact of the demographic characteristics of the co-researchers and authors on the data obtained, as it enables us to recognise the biases that are present in our findings. Though co-researchers did not discuss this issue in the focus groups, academic papers have highlighted the need for increased reflexivity in co-research studies in order to improve the rigour of the methodology (James and Buffel Citation2022). We recognise that the experiences and constructed social realities of both co-researchers and interviewees in this study are not fully representative of other ethnically or sexually minoritised older people given their level of privilege and involvement in university research. We also recognise that having ten individuals conduct interviews meant that different data were collected in different ways and that the quality of the interview data varied. Furthermore, the first author, who conducted and analysed the focus groups, is a White British, straight, cisgender woman in her early-30s and the study referred to in this article was the basis of her doctoral research. Not only will there have been some researcher bias towards how the focus groups and data were analysed, but the co-researchers’ perceptions of the first author may have influenced their responses within the focus groups (Wuyts and Loosveldt Citation2020). A selection of quotes collected from the co-researchers support this theory:

‘you young people have it tough these days. I wouldn’t want to be you. I do feel for you.’ [Margaret, Female, 79-years-old, White British]

‘you’re white, English, so young. I wouldn’t expect you to begin to understand it all.’ [Noor, Female, 58-years-old, British Pakistani]

‘my son has recently been through this [writing an academic dissertation] and I saw the stress impact on him. I will do anything to make it easier for you and that’s why I decided it was a good opportunity for me to help you.’ [Shakiba, Female, 50-years-old, Pakistani]

‘you’ve got enough on your plate and to be getting on with!’ [Frank, Male, 65-years-old, White British]

We recommend that future researchers foster critical reflection of the validity of their own data by examining the positionality and demographics of all those involved. This is especially important when working with minoritised populations given the significant power differentials that may exist between the researchers and the researched (Amann and Sleigh Citation2021; Littlechild, Tanner, and Hall Citation2015).

Limitations

This article has made some novel contributions to the co-research literature, though the study is not without limitations. A key limitation is that co-researchers were recruited from established community groups and were therefore not necessarily fully representative of the minoritised populations included. Mathie et al. (Citation2014) argue that this could reinforce the views and priorities of articulate and more privileged groups who may formally satisfy the criterion of belonging to a minoritised group, yet do not truly represent the views of that population. For example, all co-researchers spoke fluent English but some interviewees spoke little English; furthermore, all co-researchers had been involved in previous research projects or regularly attended social groups but some interviewees had never done either of those things, thus, it is likely that they had different levels of privilege. There may, as a result, be an issue with equity of access with recruiting co-researchers from established community groups. Another limitation is that interviewees were not asked about their perspectives of the co-research approach. A previous study found that some older women reported that they did not want to be interviewed by someone from their own community (Warren and Cook Citation2005). It would be useful for future research to explore how co-research is perceived by interviewees, as well as examining the benefits and challenges for them. This would further contribute to the knowledge on co-research methodologies, helping researchers to weigh up the costs and benefits of the approach for all those involved.

Conclusion

This article responds to the calls for the need for more reflection when using co-research approaches in order to promote knowledge exchange and mutual learning over the design of prescriptive rules. It addressed the gap in the co-research literature as few studies, to date, have reflected on how the co-research approach was implemented. This paper explored the practice of co-research in a study investigating loneliness amongst minoritised older people and then examined co-researchers’ reflections on being involved in the process. At the core of this paper was an examination of how inherent power and privilege from academic researchers and institutions underlie other challenges such as co-research being an extractive process, co-ownership, and time and financial constraints. It is clear that co-research methodologies should not be viewed as panaceas to institutional racism and structural injustice – using such methodologies can exacerbate inequalities rather than working to reduce them. We have suggested some ways in which to negotiate power with community partners, highlighting the importance of changing institutional expectations, priorities, and hierarchies to reflect an approach that is more aligned with the collaborative nature of co-research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Natalie Cotterell is a multi-disciplinary researcher who adopted a co-research methodology for her PhD at the University of Manchester. Her doctoral research explored experiences of loneliness among minoritised older people. Her specific research interests include working towards reducing health inequalities, using participatory methods, and improving population health.Tine Buffel is Professor of Sociology and Social Gerontology at the University of Manchester, where she leads the Manchester Urban Ageing Research Group. Issues of inequality, ageing in place, and underlying processes of spatial and social exclusion in later life have been the primary focus of her research activities. Much of her work has involved co-production methodologies, building on partnerships with older people, local authorities, and community organisations, to study and address equity and justice issues in urban environments.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akhter-Khan, S. C., and R. Au. 2020. Why loneliness interventions are unsuccessful: A call for precision health. Advances in Geriatric Medicine and Research 2 (3):e200016.

- Amann, J., and J. Sleigh. 2021. Too vulnerable to involve? Challenges of engaging vulnerable groups in the co-production of public services through research. International Journal of Public Administration 44 (9):715–27. doi:10.1080/01900692.2021.1912089.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4):216–24. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Ayre, M. L., P. J. Wallis, and K. A. Daniell. 2018. Learning from collaborative research on sustainably managing fresh water. Ecology and Society 23 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-09822-230106.

- Bermingham, B., A. Porter, and S. Cropper. 2007. Engaging with communities. Cropper, S., Porter, A., Williams, G, Carlisle , S., Moore, R., O'Neill, M., Roberts, C., Snooks, H. Community Health and Wellbeing: Action Research on Health Inequalities, Bristol, UK.: Policy Press, pp. 105–28. 9781447301936.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buffel, T. 2018. Social research and co-production with older people: Developing age-friendly communities. Journal of Aging Studies 44:52–60. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2018.01.012.

- Buffel, T. 2019. Older co-researchers exploring age-friendly communities. An ‘insider’ perspective on the benefits and challenges of peer-research. The Gerontologist 59 (3):538–48. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx216.

- Chambers, R. 2008. PRA, PLA and pluralism: Practice and theory. The Sage Handbook of Action Research Participative Inquiry and Practice 2:297–318.

- Clarke, J., J. Waring, and S. Timmons. 2019. The challenge of inclusive coproduction: The importance of situated rituals and emotional inclusivity in the co-production of health research projects. Social Policy & Administration 53 (2):233–48. doi:10.1111/spol.12459.

- Clark, A., C. Holland, J. Katz, and S. Peace. 2009. Learning to see: Lessons from a participatory observation research project in public spaces. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 12 (4):345–60. doi:10.1080/13645570802268587.

- Cotterell, N., S. Calway, A. Boswick, A. Chaudry, and W. Cudmore . 2022. Doing research together: A co-produced guide on working with older people from minority groups.

- Durose, C., Y. Beebeejaun, J. Rees, J. Richardson, and L. Richardson. 2011. Towards co-production in research with communities. Swindon, UK: Connected Communities, Arts and Humanities Research Council.

- Ellins, J., and J. Glasby. 2016. “You don’t know what you are saying ‘Yes’ and what you are saying ‘No’to”: Hospital experiences of older people from minority ethnic communities. Ageing & Society 36 (1):42–63. doi:10.1017/S0144686X14000919.

- Felner, J. K. 2020. “You get a PhD and we get a few hundred bucks”: Mutual benefits in participatory action research? Health Education & Behavior 47 (4):549–55. doi:10.1177/1090198120902763.

- Foucault, M. 1979. The history of sexuality, part 1. London: Allen Lane.

- Gardiner, C., G. Geldenhuys, and M. Gott. 2018. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health & Social Care in the Community 26 (2):147–57. doi:10.1111/hsc.12367.

- Grant, J., G. Nelson, and T. Mitchell. 2008. Negotiating the challenges of participatory action research: Relationships, power, participation, change, and credibility. Reason, P., Bradbury-Huang, H. The Sage Handbook of Action Research, London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 589–607. 9781446206584 .

- Gunaratnam, Y. 2003. Researching“race” and Ethnicity: Methods, knowledge and power. London: Sage Publications.

- Haarmans, M., J. Nazroo, D. Kapadia, C. Maxwell, S. Osahan, J. Edant, J. Grant-rowles, Z. Motala, and J. Rhodes. 2022. The practice of participatory action research: Complicity, power and prestige in dialogue with the ‘racialised mad’. 44 (S1): 106–23. Manuscript submitted for publication. 10.1111/1467-9566.13517.

- INVOLVE. 2020. Guidance on co-producing a research project. London: Author.

- Jagosh, J., A. C. Macaulay, P. Pluye, J. O. N. Salsberg, P. L. Bush, J. I. M. Henderson, E. Sirett, G. Wong, M. Cargo, C. P. Herbert, et al. 2012. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. The Milbank Quarterly 90 (2):311–46. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x.

- James, H., and T. Buffel. 2022. Co-research with older people: A systematic literature review. Ageing & Society 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0144686X21002014.

- Kalathil, J. 2013.Hard to reach? Racialised groups and mental health service user involvement. Staddon, P. Mental Health Service Users in Research: Critical Sociological Perspectives, Bristol, UK: Policy Press, pp. 121–33. 9781447307358.

- King, N. 2000. Commentary-Making ourselves heard: The challenges facing advocates of qualitative research in work and organizational psychology. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 9 (4):589–96. doi:10.1080/13594320050203166.

- Liddiard, K., K. Runswick-cole, D. Goodley, S. Whitney, E. Vogelmann, and L. Watts. 2019a. “I was excited by the idea of a project that focuses on those unasked questions” Co-producing disability research with disabled young people. Children & Society 33 (2):154–67. doi:10.1111/chso.12308.

- Liddiard, K., S. Whitney, K. Evans, L. Watts, E. Vogelmann, R. Spurr, C. Aimes, K. Runswick-Cole, and D. Goodley. 2019b. Working the edges of Posthuman disability studies: Theorising with disabled young people with life-limiting impairments. Sociology of Health & Illness 41 (8):1473–87. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12962.

- Littlechild, R., D. Tanner, and K. Hall. 2015. Co-research with older people: Perspectives on impact. Qualitative Social Work 14 (1):18–35. doi:10.1177/1473325014556791.

- Malone, R. E., V. B. Yerger, C. McGruder, and E. Froelicher. 2006. “It’s like Tuskegee in reverse”: A case study of ethical tensions in institutional review board review of community-based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health 96 (11):1914–19. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.082172.

- Markowitz, D. M. 2021. The meaning extraction method: An approach to evaluate content patterns from large-scale language data. Frontiers in Communication 6:13. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.588823.

- Mathie, E., P. Wilson, F. Poland, E. McNeilly, A. Howe, S. Staniszewska, M. Cowe, D. Munday, and C. Goodman. 2014. Consumer involvement in health research: A UK scoping and survey. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (1):35–44. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12072.

- McLaughlin, H. 2010. Keeping service user involvement in research honest. British Journal of Social Work 40 (5):1591–608. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp064.

- Minkler, M. 2004. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior 31 (6):684–97. doi:10.1177/1090198104269566.

- Minogue, V., M. Cooke, A. L. Donskoy, and P. Vicary. 2019. The legal, governance and ethical implications of involving service users and carers in research. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 32 (5):818–31. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-07-2017-0131.

- Moll, S., M. Wyndham-West, G. Mulvale, S. Park, A. Buettgen, M. Phoenix, R. Fleisig, and E. Bruce. 2020. Are you really doing ‘codesign’? Critical reflections when working with vulnerable populations. BMJ Open 10 (11):e038339. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038339.

- Ozer, E. J., S. Newlan, L. Douglas, and E. Hubbard. 2013. “Bounded” empowerment: Analyzing tensions in the practice of youth-led participatory research in urban public schools. American Journal of Community Psychology 52 (1–2):13–26. doi:10.1007/s10464-013-9573-7.

- Parveen, S., S. Barker, R. Kaur, F. Kerry, W. Mitchell, A. Happy, G. Fry, V. Morrison, R. Fortinsky, and J. R. Oyebode. 2018. Involving minority ethnic communities and diverse experts by experience in dementia research: The caregiving HOPE study. Dementia 17 (8):990–1000. doi:10.1177/1471301218789558.

- Qualter, P., K. Petersen, M. Barreto, C. Victor, C. Hammond, and S. A. Arshad. 2021. Exploring the frequency, intensity, and duration of loneliness: A latent class analysis of data from the BBC loneliness experiment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (22):12027. doi:10.3390/ijerph182212027.

- Rogers, W., and M. M. Lange. 2013. Rethinking the vulnerability of minority populations in research. American Journal of Public Health 103 (12):2141–46. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301200.

- Stoecker, R. 2009. Are we talking the walk of community-based research? Action Research 7 (4):385–404. doi:10.1177/1476750309340944.

- Tanner, D. 2012. Co-research with older people with dementia: Experience and reflections. Journal of Mental Health 21 (3):296–306. doi:10.3109/09638237.2011.651658.

- Torre, M. E., M. Fine, B. G. Stoudt, and M. Fox. 2012. Critical participatory action research as public science. In C. Harris, C. M. Paul, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Shered. APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological, Washington, DC.: American Psychological Association, pp. 171–184.

- Ward, L., and M. Barnes. 2016. Transforming practice with older people through an ethic of care. British Journal of Social Work 46 (4):906–22. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcv029.

- Warren, L., and J. Cook. 2005. Working with older women in research: Benefits and challenges. In Involving service users in health and social care research, ed. L. Lowes and I. Hulatt, 171–89. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wilmsen, C. 2008. Extraction, empowerment, and relationships in the practice of participatory research. Boog, B., Slager, M., Preece, J., Zeelen, J. In Towards quality improvement of action research: Developing ethics and standards, pp. 135–46. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

- Wuyts, C., and G. Loosveldt. 2020. Measurement of interviewer workload within the survey and an exploration of workload effects on interviewers’ field efforts and performance. Journal of Official Statistics 36 (3):561–88. doi:10.2478/jos-2020-0029.