ABSTRACT

A new participatory ecology of translation facilitated by digital technologies has significant implications for understanding translation and translators. This article examines YouTube comment translation on Bilibili in China to reconceptualize translation and translators by taking the Will Smith-Chris Rock confrontation at the Oscars 2022 and the assassination of Shinzo Abe as two illustrative case studies. It demonstrates that Chinese netizens participate in civic engagement and translate verbal and written YouTube comments into a multimodal text with various technological tools. Based on the emergent properties of YouTube comment translation, we argue that translation can be reconceptualized as an assemblage of multimodal resources that reconstitute and extend the original meanings of the source text. We also propose to expand the concept of translators to encompass both human and non-human translators, challenging the anthropocentric bias in translator studies. Finally, a post-humanist approach is suggested to reconceptualize translation and translators in the digital age.

Introduction

The discipline of translation studies (TS) has undergone significant developments in recent decades by drawing upon and bringing into play a wealth of approaches, concepts and frameworks from other disciplines such as cultural studies, sociology, communication studies and information technology. It has experienced an array of “turns” ranging from a cultural turn (Bassnett and Lefevere Citation1990), a power turn (Tymoczko and Gentzler Citation2002), a sociological turn (Wolf and Fukari Citation2007) to a technological turn (Cronin Citation2010; Jiménez-Crespo Citation2020), which have helped to facilitate its development from a marginal sub-discipline within linguistics to an autonomous and fully-fledged discipline in its own right. In this respect, it should be noted that each new turn in TS, unlike Kuhnian paradigm change characterized by revolutionary replacement, coexists with its previous turns rather than superseding them as if TS were a linear set of obsolete turns (Gambier and van Doorslaer Citation2016, 2–3; Zwischenberger Citation2019, 259).

However, despite this rapid and impressive development, TS is still considered too narrow, linguicentric and Eurocentric. It has been noted that the field of TS, in general, has become “too closed a circle” (Bassnett Citation2012, 22) and “mired in its own polemics” without giving rise to much new thinking about translation that interacts with other disciplines (Bassnett and Johnston Citation2019, 184). In consideration of the current theory of translation being not broad enough, Kobus Marais (Citation2019, 70–71) argues that the moves away from linguistic theories of translation to cultural theories of translation, social theories of translation, and power theories of translation have not been as clean as TS scholars think, since they, in essence, have failed to transcend the domain of interlinguistic translation. In response to anthropocentric and glottocentric biases prevalent in current studies, he advocates expanding the scope of TS by adopting a (bio)semiotic theory of translation based on the developments in biosemiotics and Peircean thought on semiotics (Marais Citation2019). In a similar fashion, several other scholars have shown a keen awareness of the importance of bi-directional exchanges between TS and other disciplines, having looked outwards to address the issue of translation outside its disciplinary borders (Blumczynski Citation2016; Gambier and van Doorslaer Citation2016; Bassnett and Johnston Citation2019; Vidal Claramonte Citation2022; Zwischenberger Citation2023). Moreover, new forms of translation practice facilitated by technological innovation and globalization also call into question the traditional understanding of translation and translators, compelling us to reexamine such concepts in line with these new developments (Cronin Citation2010; van Doorslaer Citation2020; Gambier and Kasperẹ Citation2021; Yang Citation2020; Yang Citation2021). In addition, Eurocentrism is a persistent problem in TS, which even runs the risk of “instantiating a form of twenty-first century colonialism” (Bassnett and Johnston Citation2019, 181). Therefore, it is imperative to absorb a plurality of voices from across the global community to facilitate the geographical extension and internationalization in the theorization and conceptualization of translation and translators, taking into account the different cultural climates and traditions (Tymoczko Citation2010; Bassnett and Johnston Citation2019, 181; van Doorslaer and Naaijkens Citation2021). In this context, it is time for translation scholars to expand their ideas about translation beyond glottocentric and Eurocentric perspectives, and to seek a reconceptualization of translation and translators emanating from new translation phenomena and practices.

New media cultures and technologies have offered fertile ground for the emergence of novel translation phenomena and practices, constituting the most promising critical line for rethinking translation and translators (O’Hagan Citation2020; Mus Citation2021; Bielsa Citation2022). It is also noteworthy that, although translator studies have gained momentum in recent years, most studies have focused on literary translators with little attention paid to a broader sense of translators represented in the digital age (Chesterman Citation2009; Kaindl Citation2021). Given such a context, the present study focuses on YouTube comment translation (thereafter, YCT) on Bilibili, a popular video-sharing social media website in China, to shed light on the impact of digital technologies in redefining the concept of translation and translators. Specifically, the present study will examine the characteristics of YCT by drawing on two vlogs on Bilibili, about the Will Smith-Chris Rock confrontation at the 94th Oscars ceremony, and the assassination of Shinzo Abe, as illustrative cases. By probing into this new translation practice, conducted voluntarily by grassroots Chinese netizens, this study aims to reconceptualize translation and translators in tune with the multimodal communications prevailing in the digital age.

Research background

The development of digital technologies and proliferation of social media platforms in the twenty-first century have exerted a significant impact on translation practice, contributing to a rethinking of what constitutes translation and the role and position of the translator (Cronin Citation2010, 1; van Doorslaer Citation2020, 142). The affordances of digital technologies not only provide new platforms and media through which translation activity is undertaken but also facilitate the digital convergence between production and consumption, enabling the consumers of translations to become translators. Consequently, the translator no longer employs a target-oriented model of translation in the service of an audience, but rather the audience produces their own self-representation as a target audience (Cronin Citation2013, 100). In the era of Web 2.0, the second generation of the internet that is characterized by its open, participatory and interactive nature, a myriad of new forms of translation practice such as fan translation, volunteer translation and online social translation have been thrust into the limelight (Olohan Citation2014; McDonough Dolmaya and del Mar Sánchez Ramos Citation2019; Wongseree Citation2020). These new translation practices are mainly carried out by non-professional translators in a collaborative way, which spurs scholars in TS to extend their focus from professional translators and their solitary practice to include non-professional translators and online collaborative translation (Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva Citation2012; Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017; Zwischenberger Citation2022).

Despite such efforts to broaden the object of research in TS outline above, some scholars (e.g. Vassallo Citation2015; Mossop Citation2017) continue to display a persistent penchant for a narrow understanding of translation as interlingual transfer and emphasize equivalence and the transmission of invariant and stable meaning during the translation process. However, such a restricted conception of translation and translators, as Zwischenberger (Citation2019, 266) argues, is “particularly damaging to the discipline because it perpetuates perceptions of ‘translation proper’ and consequently also of TS as outdated”. Resonating with Zwischenberger’s opinion, we argue that it is necessary to update our understanding of translation and translators in light of the new translation landscape resulting from the development of digital technologies, to help TS become more inclusive and heuristic. We also support the view that translation is an open, complex and polymorphous concept in a perpetual state of flux, defying a comprehensive and clear-cut definition, as it always needs to be negotiated and questioned based on the data, research methods and perspectives selected by the scholars (Tymoczko Citation2010, 53; Hermans Citation2013, 75; Blumczynski Citation2016, xii; Gambier and Kasperẹ Citation2021, 48). In this regard, instead of carving out a one-size-fits-all definition of translation and translators for universal use, we aim to provide a new understanding of these concepts by examining YCT emerging from China’s Bilibili, thereby enriching our perception of the multifariousness of translation and translators in the digital age.

Participatory translation in the digital culture

The development of digital technologies has brought about a new participatory ecology of translation in the era of Web 2.0 which encourages netizens to participate in social networking, share ideas and generate their own works. Digital technologies have also transformed the way in which translations are produced, distributed and consumed. Commonly acknowledged as a professional activity, translation has conventionally been carried out by trained translators who had previously acquired the relevant expertise. By contrast, with digital technologies permeating all aspects of our life and society nowadays, an increasing number of non-professional translators, equipped with translation technologies such as translation memories, terminology corpus and machine translation tools, are embarking on executing complex translation tasks. They often act as initiators of translation projects, personally claiming the right to decide what is to be translated in their own hands; this stands in stark contrast to the scenario in the age of print when patrons always had overwhelming power in the translation process. They translate for free and distribute their translations online through various social media platforms for the consumption of other users in order to share interests, spread knowledge and build community.

To describe such new translation practices arising from the burgeoning digital technologies, scholars have coined a plethora of new terms based on their various research foci and perspectives. Drawing on the concept of “user-generated content”, Minako O’Hagan (Citation2009, 97) invented the term “user-generated translation” to indicate “a wide range of Translation, carried out based on free user participation in digital media spaces where Translation is undertaken by unspecified self-selected individuals”. Later, O’Hagan (Citation2011) proposed the term “community translation” that accentuates the connections between these new forms of translation and online communities in the context of Web 2.0. Luis Pérez-González and Şebnem Susam-Saraeva (Citation2012) chose the concept “non-professional” or “amateur translation”, bringing to the fore the growing body of non-professional translators engaging in translation activities in the digital age. Paying special attention to the participatory and interactive nature of the Web 2.0, Miguel Jiménez-Crespo (Citation2017) uses the terms “translation crowdsourcing” and “online collaborative translation”, pointing to the collaboration among translators as the intrinsic feature of online translations. In a similar fashion, focusing on the translation that takes place on social media platforms, Julie McDonough Dolmaya and María del Mar Sánchez Ramos (Citation2019) advocate for the term “online social translation” for designating such translation practice and view collaboration as its visible and inherent feature. With the aim of reflecting the technological turn in TS and the role of social media as a medium for translation, Gernot Hebenstreit (Citation2019) proposes the top-level term “social-media-driven translation”.

These terms are somewhat overlapping and intimately bound up with each other. According to O’Hagan (Citation2011, 11), community translation is viewed “more or less synonymously with such terms as translation crowdsourcing, user-generated translation and collaborative translation”. Translation crowdsourcing is not only closely related to online collaborative translation, but also can be subsumed under the latter category, since both of them are primarily carried out by volunteers with no, or extremely low, monetary compensation and all “crowdsourcing” efforts are basically collaborative in essence (Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017, 19–20). Built upon O’Hagan’s concept of “community translation”, “online social translation” overlaps to a great extent with “translation crowdsourcing” and “online collaborative translation” in that it includes both bottom-up translation initiatives self-organized by web users and top-down translation initiatives with the locus of control residing in the organizations and companies calling for translation (Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017, 25; McDonough Dolmaya and del Mar Sánchez Ramos Citation2019, 132–133). In addition, most of these new translation practices online, ranging from “user-generated translation”, “community translation” and “online collaborative translation” to “online social translation”, fall within the category of non-professional translation, albeit potentially with the involvement of some professional translators.

At the same time, apart from their connections and similarities, these terms have nuanced differences. Drawing on a fine-grained and comparative analysis of such terms as “community translation”, “user-generated translation”, “translation crowdsourcing”, “online social translation” and “online collaborative translation”, Zwischenberger (Citation2022) elucidates the focus and characteristics of each term and spells out the differences among them. For example, with regard to the difference between “community translation” and “translation crowdsourcing”, Zwischenberger (Citation2022, 4) points out that “the various forms of unsolicited and self-managed online collaborative translation such as fansubbing are based on a community with a group consciousness and self-management”, whereas “translation crowdsourcing” usually involves a large and unspecified mass of people or crowd who are managed by the instigating institution and do not themselves decide which text to translate. Viewing collaboration as a common denominator of the new ways of doing translation online, Zwischenberger (Citation2022, 7) argues that “online collaborative translation” is the most suitable superordinate concept to cover all the new translation practices that take place on the online platforms.

It is undeniable that collaboration constitutes a salient feature of online translation activity, as has been shown by an array of scholars (Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017; Hebenstreit Citation2019; McDonough Dolmaya and del Mar Sánchez Ramos Citation2019). However, as O’Hagan (Citation2011, 16) points out, whether translation has truly become collaborative in involving the masses on the internet remains an open question that needs to be further explored. In this respect, we argue that not all translations carried out online are necessarily collaborative. In fact, none of the aforementioned terms accurately describes YCT on Bilibili which, as will be demonstrated, is carried out voluntarily by grassroots users in cyberspace, and is in most cases an individual rather than a collaborative act of civic participation in China.

YouTube comment translation on Bilibili

As elements of foreign popular culture, cultural products and media are imported into China on a massive scale, it is noteworthy that Chinese government exercises direct or indirect state control and censorship to ensure that circulated media products are in line with its dominant political ideology (Zhang and Mao Citation2013, 49; Wang and Zhang Citation2017, 303–305). Wary of the impact of foreign audiovisual products on YouTube, a video-sharing platform controlled by the American conglomerate Alphabet, China is one of a small number of countries in the world where the operation of YouTube is blocked by the government. By so doing, the Chinese government aims to preempt the potential negative influence on its citizens of the wide circulation of online contents on YouTube, thus curtailing the soft power produced by Western cultures and ideologies. Consequently, the online contents on YouTube are inaccessible to users in China through its official outlet. YCT on Bilibili is thus a distinctive translation practice in China afforded by digital technologies, since it enables viewers in China to access foreign contents from a banned social media platform.

The emergence of media and digital technologies provides the Chinese government with new tools to enforce censorship on the media in the cyberspace. In parallel, these tools also allow the grassroots Chinese netizens to participate in the creation and distribution of media content that circumvents the restrictions imposed by the government. As Dingkun Wang and Xiaochun Zhang (Citation2017, 305) point out, it is often the case that “the very same technologies harnessed for political and ideological control may be utilized by audiences to gain freedom from state domination”. These Chinese netizens are no longer passive consumers but rather become active producers or prosumers, who have a good knowledge of the needs of their audience and make every effort to satisfy them.

As the largest video-sharing platform in China, Bilibili acts as one of the facilitators for user-generated contents, boasting all kinds of video genres uploaded by users including anime, comic, video games, music, technology, documentaries and news. With the aid of Bilibili and various digital technologies, Chinese netizens contribute to the dissemination of knowledge and information from the otherwise banned YouTube website via translating its comments in a creative way. The translated comments from YouTube on Bilibili cover topics ranging from pleasure-seeking entertainment to cultural and social events in China and overseas. Their extensive coverage on the topics of cultural and social events in addition to the entertainment reflects the translators’ engagement with cultural and social issues for the public good, which can be seen as an embodiment of their efforts for civic engagement (Zhang and Mao Citation2013, 54). The translators often do not expect any material rewards for their work and devote themselves to helping people gain access to different ideas and perspectives, although it is the case that they may be rewarded with e-gifts by their fans and ordinary viewers on Bilibili. Regardless of the topics of the YouTube comments they select for translation, the very action of translating comments from YouTube videos and uploading them on Bilibili to share knowledge and create diversity of viewpoints also has civic implications. In this regard, YCT on Bilibili can be understood as a civic translation that is vulnerable to censorship in the Chinese context, although it is not an explicitly politically-driven activity.

YCT on Bilibili refers to the practice whereby grassroots users of the social media platform Bilibili translate verbal comments on the videos from YouTube into multimodal texts, with recourse to a variety of semiotic resources, catering to the recipients’ demands for Web-based multimodal materials and the community-building cultivated by the new media and participatory ecology of the digital age. It thus involves not only interlingual rendition but also intersemiotic transfer, traversing linguistic and semiotic boundaries. The translations are carried out by these users of Bilibili in a spirit of volunteerism, do-it-yourself and sharing. The creation of the multimodally translated product of YouTube comments is a complicated process that encompasses the steps of searching for relevant videos on YouTube, selecting comments, translating and editing them, and making videos with the help of diverse digital tools and software. In this regard, it is tempting to assume that such a complicated translation process is completed by a team with various skills and that the translated product is the result of online collaborative translation.

However, based on the information attached to the videos of YCT on Bilibili and the uploaders’ interactions with their audience in the user comment sections identified in the present study, the translations seem much more likely to be individual rather than collaborative acts, which resonates with the outcomes of other scholars’ investigations. In their survey via questionnaires and interviews of how comment translation activity (including YCT) on Bilibili is conducted, Ding et al. (Citation2021, 183) reveal that 25 out of 30 participants completed the entire translation process on their own, although assisted by machine translation tools and video-editing software. Notably, their survey also indicates that most of the participants have received higher education with bachelor’s, master’s and even doctoral degrees, but only two of them have received professional training in translation and dedicated themselves to a translation-related work (Ding et al. Citation2021, 179–180). Hence, although the survey data were not exhaustive, it is reasonable to argue that YCT on Bilibili is most likely contributed by individual non-professional translators with digital support, who do not necessarily have excellent language competence typical of professional translators.

As a translation practice carried out by self-selected individuals, YCT on Bilibili has the following characteristics. Firstly, the initiator of the translation is primarily an individual netizen who simultaneously assumes the roles of commissioner, translator and consumer, rather than corporations or institutions such as Facebook translation and TED translation. By contrast, online collaborative translation such as fansubbing, community translation or crowdsourced translation is often initiated by a self-organized community, a company or an organization, which invites translators to complete a translation task in a collaborative way (O’Hagan Citation2011; Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017). In the latter practices, the translation activities are well organized with translation management systems that control the translation process and allocate different roles and responsibilities to relevant participants, resulting in a hierarchy among the translation participants (Jiménez-Crespo Citation2017, 22; Wang and Zhang Citation2017, 309). Unlike such online collaboration translation, individual translators in YCT have overall control of the translation process, deciding what comments from YouTube are to be translated and how to translate them. The translation products can thus reflect the translators’ own viewpoints and willingness to reach out to certain target audience.

Secondly, the translators of YCT on Bilibili work as multitaskers. According to Gunther Kress (Citation2020, 42), “translation is the reconstitution of meaning for specific others”. Following this reasoning, YCT is an act of translation that reconstitutes the meaning of the comments from YouTube for Chinese netizens by means of semiotic resources. Furthermore, the translators go beyond the transfer of the linguistic meaning of the comments by capitalizing on a variety of semiotic resources such as sounds, colors, images and music for making meanings, transforming the verbal YouTube comments into an aural and visual experience. In order to combine the various modalities to generate a composite translation product, the individual translators become multitaskers who play multiple roles such as translating the comments from YouTube, remixing videos and images, and recording voices and editing videos by leveraging the affordances made available via digital technologies. Therefore, it is essential for the translators to simultaneously possess linguistic, cultural, technological, editorial and presentational skills.

Thirdly, digital technologies play a crucial role in facilitating the YCT on Bilibili. As YouTube is banned in China, Chinese netizens use VPNs (virtual private networks), masking their location and bypassing the government-enforced firewall, to seek out a wider palette for information through accessing social media platforms such as YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. The wide and free availability of machine translation tools such as Youdao Translate, Baidu Translate and Google Translate allow netizens who are not fully conversant with foreign languages and cultures to engage in the translation of YouTube comments, although the translation quality may not reach professional standards. The availability of video-editing software makes it possible for the translators to assemble different resources related to the selected YouTube comments and to create extended and expansive semiotic repertoires around the translated comments to circumvent governmental control. Finally, Bilibili acts as a viewing and sharing platform where the multimodal translated YouTube comments can be disseminated and consumed by netizens. It is worth noting that Bilibili is renowned for its danmu (a commenting facility, literally “bullet curtain”) function, which allows viewers to upload live comments onto the video to interact with other viewers, contributing to the construction of virtual community (R. Wang Citation2022). In this sense, Bilibili also acts as a community-building platform for like-minded users to come together and develop relationships. Its community-building function serves as a driving force for other netizens to join them to translate and share YouTube comments.

In the next two sections, we will look in more detail at two case studies of YCT on Bilibili to explore how multimodal translation is created for civic engagement in China and reveal the significance of the collaboration between human and non-human actors in translation. The rationale for selecting the following two videos for our case studies is twofold. First, both of them present recent incidents that have gained global attention. Second, they both contain new translation practices that are conducive to the rethinking of translation and translators that is central to our study. Based on the two case studies, we aim to gain new insights into translation from a multimodal perspective and expand the concept of translators to encompass non-human actors in the digital age.

Case 1: Will Smith-Chris Rock confrontation at the 2022 Oscars

At the Oscars ceremony on March 27, 2022, an event unfolded in an unpredictable way: the Best Actor winner Will Smith slapped the presenter Chris Rock across the face live on camera. Rock was invited to attend the Oscars to announce the winner for the Best Documentary. Before his announcement of the award, Rock, as a comedian, made several jokes about the guests present at the ceremony, with one of the jokes directed towards Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith, associating her bald head with that of Demi Moore in the 1997 movie G.I. Jane. It is known to the public that Jada has been battling with alopecia, a disease leading to hair loss, which forces her to shave her head. Although initially laughing from his seat when hearing the joke, Will Smith suddenly made his way onto the stage and smacked Chris Rock across the face when he became aware of the annoyed expression on Jada’s face, and further cursed Rock loudly back in his seat after the slap. This incident brought an unanticipated surprise to the Oscars telecast, which attracted worldwide attention. The recorded video clip about Smith’s violent encounter with Rock at the awards show immediately caused a sensation on YouTube and gave rise to many comments. This incident also drew the attention of grassroots Chinese netizens, who uploaded their translated versions of some YouTube comments on Bilibili to help other Chinese netizens to access alternative perspectives of the incident.

This section will take a vlog of translated YouTube comments on the event of Smith’s slapping Rock at the 2022 OscarsFootnote1 as a case study, aiming to provide a new perspective on translation and translators in the digital age. The vlog begins with an edited and dubbed video clip of Smith slapping Rock to contextualize the translation of the YouTube comments that ensued. Instead of translating the original spoken dialogue in the video, the dubbing is in fact a gist translation, which is an emergent and popular form of translation in the digital age (Cronin Citation2013, 7). It retells the main narrative provided by the video: Will Smith walked onstage and slapped comedian Chris Rock across the face in front of the Oscars ceremony audience after Rock made a joke about Smith’s wife shaved head. Meanwhile, it also translates the characters’ facial expressions and dynamic actions into words and speech. As a result, the translator has produced a translation that combines verbal, visual, acoustic and kinesic elements in a creative manner to convey the import of the incident.

Approaching the end of the video clip, the translator observes, “该事件迅速引起美国民众的热议/下面是一些美国网友评论/一起来看看吧” (“this incident immediately spawned a heated discussion among American people / What follows are some comments from American netizens / Let’s have a look”). The sentence, “Let’s have a look”, indicates the translator’s eagerness to directly engage with audience and interact with them, reducing the distance between translator and audience. Following this observation, the translator also asks the audience to note that, “中美文化,价值观不同/主流观点和中国不同” (“due to the differences in values between Chinese and American cultures / the mainstream opinions are different from those in China”). With a view to attracting audience’s attention to this note, the translator uses technological means to insert three dynamic dashed arrows to mark it (see ). In this way, the translator introduces an additional layer of representational content and offers interpretations of the ensuing comments on the incident, setting in motion the narrative of the vlog in a more participatory and immersive way. This unconventional note also facilitates a creative interaction between the translator and the audience, allowing the translator’s personal thoughts and opinions to strike a chord with the audience. In this regard, it can be argued that the observation and creative note together serve as a vehicle for the translator to express personal opinions and foster a sense of community.

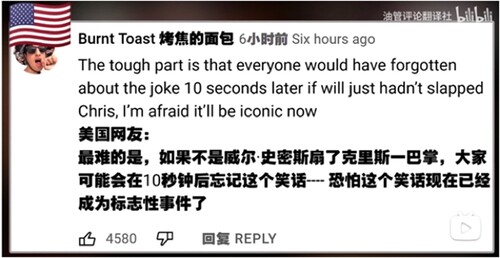

Following the video clip, the vlog presents eleven translated YouTube comments on the incident, which are selected by the translator from the copious comments on the YouTube website. Relying on their technological expertise, the translator creates parallel and bilingual versions of these YouTube comments, with the original English comment displayed together with its Chinese translation (see ).

When examining the translation of tweets in Spanish digital newspapers, María José Hernández Guerrero (Citation2020, 382) argues that “the reproduction of the original tweet strengthens its credibility and the coexistence of the original and the translation in the same space affects the visibility of translation and the audience’s perception of it”. From this perspective, with the original English comment as a credibility indicator, the uncensored nature of the translation is brought to the fore, which makes the translation more reliable and trustworthy for the audience to access alternative perspectives and broaden their horizons. By selecting the YouTube comments for translation and presenting their translations in a credible way, the translator takes on a civic responsibility, spreading alternative views for the public good. Furthermore, the translator uses bold font to highlight the translation and inserts an image of the American flag at the top left side to indicate the nationality of the netizen who provides the comment. In addition to presenting the translation in a written form, the translator also reads out the translation for the audience, with background music. The melodious sound in the background adds an extra performative element to the translator’s oral presentation of the translation, contributing to an enhancement of the overall auditory experience for the audience. In this way, the translator has strategically rendered the monomodal text of a YouTube comment into a multimodal text that combines sound, image and written words, creating an entire multi-sensory experience for the target audience for the otherwise inaccessible contents.

Case 2: the assassination of Shinzo Abe

Japan’s former Prime Minster Shinzo Abe was assassinated on 8 July 2022 when he was giving an Upper House election campaign speech in Nara. In the aftermath of the unprecedented shooting of Abe, people from many countries expressed shock and grief, praying for his recovery, although no vital signs were detected by the time he was transferred for treatment (Tan and Murphy Citation2022). In a similar vein, acknowledging Abe’s contribution to the improvement of China–Japan relations, the Chinese President Xi Jinping “extended deep condolences on the sudden and unfortunate passing of Abe on behalf of the Chinese government and people and himself, and expressed sympathies to the family of Abe” (Xu Citation2022). However, due to Abe’s complex legacy and the longstanding historical fissures between China and Japan, divided reactions towards his assassination appeared in China, with many Chinese netizens showing little sympathy for him and offering hostile comments over his death on Weibo, a prominent social media platform in China (W. Wang Citation2022; White Citation2022).

Like Chinese netizens, people in other countries also paid significant attention to the breaking news of the attack on Abe and his death, contributing their views in the comment section on YouTube. Some Chinese netizens thus selected and translated the YouTube comments in a tactical and creative way on Bilibili to circumvent censorship and open novel pathways for the presentation of Western views on the incident. This section will draw on a vlogFootnote2 about the translated YouTube comments on the incident of Shinzo Abe’s assassination to provide a fresh understanding of translation and translators. While the original YouTube comments are available in written and spoken forms, the translation is presented in a multimodal format with a combination of images, sound and written words, achieved via technology-mediated interventions by the translator.

The vlog starts with a remix of footage of Abe giving his speech on the street, the chaotic situation caused by the shooting and the security guard’s tackling of the suspected gunman at the scene of the attack, which is accompanied by the translator’s voice-over. The voice-over provides a concise introduction to the incident noting that Japan’s former Prime Minster Shinzo Abe was attacked and died in spite of rapid medical treatment. Regarding its shortness of the introduction to the incident, it explains that “为了过审尽量简短介绍” (“keeping the introduction as succinct as possible aims to ensure its passage through censorship”) (see ). This explanation reveals the translator’s full awareness of the sensitiveness of the incident in China and possible censorship of the translation. Despite the potential censorship, the translator continues to resist the dominant and hostile narratives concerning Abe that circulated on the Chinese internet by translating favorable comments about him from other countries in a tactical way, delivering them to the target constituencies. In this way, the translator becomes an important player in Chinese civic life, practising “nonconfrontational activism” that makes incremental and piecemeal changes for the social good (Wang Citation2019, 56). Hence, facilitated by digital technologies, the remix of footage interspersed with the translator’s explanation opens up “new possibilities for more democratic spectatorial engagement by bringing the world of the story closer to the space of the audience” (Pérez-González Citation2020, 105). Moreover, the translator also addresses directly target audience in the vlog by greeting them with, “大家好欢迎来到YouTube网友评论” (“Hello everyone, welcome to netizens’ comments on YouTube”). By so doing, the translator opens up an affinity space with the audience of the translated audiovisual text in question.

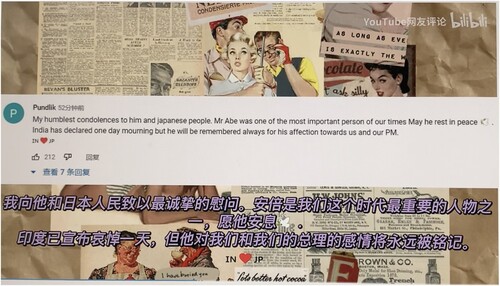

Ensuing from the remix of footage, translated YouTube comments on the assassination and death of Abe constitute the rest of the vlog. With technological tools, the translator incorporates moving images of a countdown from three to one into the translation to facilitate the transition from the introduction of the incident in the remix to the comments on it, thereby channeling the audience’s attention onto the translations of the YouTube comments. As exemplified by the comment shown in , the selected YouTube comments are primarily from Indian netizens who show respect for Abe and send condolences to his family and the Japanese people, which is diametrically opposite to the condemnation of Abe’s unforgiveable behaviors and the celebration of his death displayed on China’s internet (W. Wang Citation2022). It is also worth particular attention that, as shown in , the bilingual version of the YouTube comment is presented in the middle against a background consisting of several still images that include elements such as sexy women, smiling faces, hugs, tea drinking and tabloids. These background images generate an atmosphere of happiness, comfort and enjoyment, which stands in striking contrast to the sadness and seriousness displayed in the comment. By juxtaposing these background images with the comment using technological devices, the translator invests conflicting attitudes and feelings into the original perspective, producing a sardonic and ironic translation congruent with the dominant and hostile discourse on Abe’s assassination in China’s internet environment (White Citation2022). In sum, having mastered the art of exploiting semiotic resources to the fullest extent, the translator opens up a translational space where written and spoken language interacts with still and moving images and sound in productive ways, creating a multimodal translation with civic implications.

Discussion: reconceptualizing translation and translators

Digital technologies are increasingly bringing about a world that is moving towards multimodal communication. To reconceptualize translation and translators in the digital era, it is necessary to be “aware of surroundings as well as the context of social and technological change in which the translator currently works” (Vidal Claramonte Citation2022, 15). As our cases demonstrate, the grassroots Chinese netizens are able to exploit various technological tools to translate English YouTube comments into a coherent multimodal text with recourse to visual, auditory and other sensory channels, making available the otherwise inaccessible content to Chinese audience via the internet. Like a screen adaptation of a novel, YCT incorporates new modes that are not used in the original text. As shown in , the translators have mobilized visual and auditory modes as meaning-making resources to complement the translation of YouTube comments at the linguistic level. In this sense, YCT on Bilibili is not a linear source-to-target transmission but rather embodies a rhizomatic development fostering connections with the source text “in different directions and evolving new, nonlinear formations” (Lee Citation2023, 380). Consequently, it goes beyond interlinguistic translation and produces multimodal translation by drawing on the full range of non-linguistic meaning-making resources afforded by the Chinese language, diverse modes and the Bilibili platform.

The development of digital technologies also foregrounds the role of non-professional translators and the interactions between human and non-human actors in the translation process. Translators in the digital age move away from “the monadic subject of traditional translation agency – Saint Jerome alone in the desert – to a pluri-subjectivity of interaction” (Cronin Citation2013, 102). In the case of YCT on Bilibili, it is often carried out by individual non-professional translators with the assistance of non-human actors such as the Bilibili platform, machine translation tools, video editing software and recording devices. The non-human actors equip translators with new resistant and subversive resources which enable them to produce translational remixes to create hybrid narratives and negotiate alternative interpretations in response to censorship in China (D. Wang Citation2022, Citation2023). The translators act as designers of the translation product, and exercise full discretion over which YouTube comments are to be translated and how.

As our cases demonstrate, by utilizing various technological tools to mobilize semiotic resources such as dynamic dashed arrows, bilingual presentation and images, the translators creatively engage with the original English YouTube comments for the purposes of self-expression, community-building and civic engagement. While official channels like the WeChat subscription account of Reference News promote mainstream ideologies via careful selection of overseas netizens’ comments (Zeng and Li Citation2023), the YCT on Bilibili allows translators to contest dominant narratives of the incidents in China. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that their translations are not inherently activist, and can be considered as a combination of resistance and compliance. The YCT related to the Will Smith-Chris Rock confrontation demonstrates sympathy for Rock by turning the viewers’ attention to his identity as a comedian and actor, challenging the mainstream support for Smith for protecting his family in China. By contrast, the YCT concerning the assassination of Abe reflects the translator’s paradoxical attitudes towards Abe by displaying favorable comments about him in a sarcastic way, echoing the hostile narratives of Abe dominant in the Chinese internet.

Despite the fact that the translators have much control over their translation activities and are empowered by the technologies in our case studies, “the control exercised by the technology itself should not be underestimated” (Hebenstreit Citation2019, 146). As a video-sharing and community-building platform, on the one hand Bilibili provides a venue for translators to share their translated YouTube comments in China, and on the other it determines the multimodal outcomes of their translations in meeting the expectations of their potential audience. From this perspective, Bilibili plays a crucial role in shaping the production of the YCT. Moreover, it is also impossible for grassroots Chinese netizens to provide a composite and multimodal translation product of YouTube comments without resorting to these various technological tools which thus serve as important instruments for the translators’ civic engagement, helping them to circumvent state censorship and access the otherwise banned contents.

Based on the above two case studies, we argue that translation in the digital age is much more complicated in meaning-making than the established notion of interlinguistic transfers, encompassing the transformation of modalities derived from the interactions of human translator and technology. It is noteworthy that some scholars have paid attention to the role of non-human actors in translation studies. For example, Wenyan Luo (Citation2020) elaborates on the role of non-human actors, such as the Second World War, the source texts and translations, and letters between major human actors in Arthur Waley’s English translation of the Chinese classic Journey to the West. Some scholars examine the implication of non-human actors, such as technological tools, translation project communities and digital software, on translation practices taking place online (Cronin Citation2013; Kung Citation2021; Lee Citation2023; Mihalache Citation2021). However, while recognizing the role of non-human actors in the translation practice, these studies do not fully acknowledge the “non-human agency”, and thus still stop short of viewing non-human actors and human actors on an equal footing. By contrast, as our case studies demonstrate, the non-human actors, such as machine translation tools, Bilibili platform and video-editing software, play as important role as non-professional human translators in creating a multimodal translated version. Moreover, with the development of artificial intelligence, big data and cloud computing, we are entering an era of automation in which machine translation becomes increasingly sophisticated, even penetrating translation of literature and other creative texts (Hadley et al. Citation2022), and engendering the possibility of human-machine parity in translation (Läubli et al. Citation2020).

In this context, we argue that it is time to apply post-humanist perspective, which has widely been used in disciplines such as science and technology studies, cultural studies and sociology (Latour Citation1993; Hayles Citation1999; Wolfe Citation2010; Braidotti Citation2013), to translation studies as well. Adopting a post-humanist perspective offers a new epistemology for translation studies that contributes to the breakdown of the traditional boundaries between the human and the technology, and to the cultivation of the symbiotic relationship between them (O’Thomas Citation2017; Carl Citation2022). From this perspective, rather than seeing non-human actors as important factors that affect translation, we propose to conceptualize non-human actors as translators in their own right. In line with the way of viewing animals as non-human translators in the inter-species translation (Cronin Citation2017; Marais Citation2019; van Vuuren Citation2022), the proposal of non-human translators including technological artefacts and digital tools in our study, does not mean an abolition or replacement of the role of human translators but an expansion of the terrain in which it is constituted, offering a spectrum through which we can capture the complexity of emergent translation practices in the digital age. As such, the concept of translators is expanded to include both human and non-human translators, challenging the anthropocentric bias in current translator studies (Chesterman Citation2009; Kaindl Citation2021).

Conclusion

The irreversible trend of increasingly powerful digital technologies becoming available to netizens has torn down the boundary separating consumers and producers of translations, and bestowed agency on non-professional translators for civic engagement. As our research reveals, by taking advantage of various digital technologies, the grassroots Chinese netizens have become prosumers of YCT on Bilibili. Acting as translators, they employ highly interventionist mediation strategies to take on civic responsibilities, making banned YouTube comments available to their Chinese audience through multimodal translation. Drawing on a spectrum of semiotic resources, the translators add more meaning to the original YouTube comments by translating them into a composite and multimodal text, and creating a multi-sensory experience for their target audience. They enjoy great visibility and freedom in the translation process, exploiting translation as a means of self-expression, community-building and nonconfrontational activism. Our study also highlights the importance of non-human actors such as the Bilibili platform, machine translation tools and video-editing software, which determine how translations are produced, presented, distributed and consumed. Based on these emergent properties of YCT on Bilibili, we argue that translation has ceased to be merely interlinguistic transfer and can be reconceptualized as an assemblage of multimodal resources that reconstitute and extend the original meanings of the source text. With regard to the concept of translators, we challenge the fetishization of human translators and suggest embracing and recognizing the importance of a collaborative translation approach between human and non-human actors in the digital age.

By reconceptualizing translation from a multimodal perspective, our study is conducive to fostering multimodal translation studies. Meanwhile, our expanded understanding of translation and translators is derived from our study of YCT on Bilibili in the Chinese context, which is thus not a static truth, but needs to be constantly reflected upon and critically reevaluated in terms of different translation practices and contexts. In this regard, since YouTube is also banned in other countries such as Iran, South Sudan and Turkmenistan, it is important to examine how far similar translation practices take place in these countries expanding non-European understanding of translation and translators in the digital age. In addition, the concept of translation will surely continue to evolve in line with the development of new digital technologies, making the reconceptualization of translation and translators a never-ending topic.

In a world in which translation is ubiquitous (Blumczynski Citation2016), it is natural that translators will also become ubiquitous with human translators increasingly living in synergy and partnership with non-human translators. Correspondingly, we propose to adopt a post-humanist approach to conceptualizing translation and translators. From this perspective, we are able to dissolve the subjectivity/objectivity boundary between human translators and non-human translators, and foster trans-disciplinary translation studies to cope with the trend of de-centering of the human in translation practices in the age of automation and digitalization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Binghan Zheng

Binghan Zheng is Professor of Translation Studies at Durham University, where he is the Director of the Centre for Intercultural Mediation. His research interests include cognitive translation/interpreting studies, neuroscience of translation, and comparative translation/interpreting studies. His recent publications appeared in journals such as Target, Across Languages and Cultures, Journal of Pragmatics, Brain and Cognition, Perspectives, Translation and Interpreting Studies, and Foreign Language Teaching and Research. He has guest-edited the special issue “Towards Comparative Translation & Interpreting Studies” (2017) of Translation and Interpreting Studies (with Sergey Tyulenev), and his monograph Translation Process Research: Theories, Methods and Issues is forthcoming in 2023.

Jinquan Yu

Jinquan Yu is a postdoctoral researcher at Sun Yat-sen University, China, who received his PhD in translation studies from Bangor University, UK. His research interests include media and translation, translation and paratexts, and sociology of translation. His recent works have been published in journals such as The Journal of Specialised Translation, Perspectives, Babel, Archiv Orientalni, and Translation Quarterly.

Boya Zhang

Boya Zhang holds a PhD in museum studies from Durham University. Her research interests include museum exhibition and translation, visual arts and cultures, and art history.

Chunli Shen

Chunli Shen received her PhD in translation studies from Bangor University, UK. She is currently a lecturer in School of Foreign Languages and Literatures at Hangzhou Dianzi University, China. Her research interests include translation and reception, translation and ideology, and translation and gender.

Notes

1 See https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV16S4y1N7wa?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=aa867d48161daf9094e83c3a76e8dc22, accessed on June 18, 2022.

2 See https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV13a411p7sd?spm_id_from = 333.337.search-card.all.click&vd_source = aa867d48161daf9094e83c3a76e8dc22, accessed on July 11, 2022. This video was later found to be removed by the uploader for unknown reasons. Readers who are interested in viewing this video could request for it from the corresponding author, and the video is for private use only.

References

- Bassnett, Susan. 2012. “Translation Studies at a Cross-roads.” Target 24 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1075/target.24.1.02bas.

- Bassnett, Susan, and David Johnston. 2019. “The Outward Turn in Translation Studies.” The Translator 25 (3): 181–188. doi:10.1080/13556509.2019.1701228.

- Bassnett, Susan, and André Lefevere, eds. 1990. Translation, History and Culture. London: Pinter.

- Bielsa, Esperança, ed. 2022. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Media. London: Routledge.

- Blumczynski, Piotr. 2016. Ubiquitous Translation. London: Routledge.

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

- Carl, Michael. 2022. “An Enactivist-Posthumanist Perspective on the Translation Process.” In Contesting Epistemologies in Cognitive Translation and Interpreting Studies, edited by Sandra L. Halverson, and Álvaro Marín García, 176–189. London: Routledge.

- Chesterman, Andrew. 2009. “The Name and Nature of Translator Studies.” HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business 42: 13–22. doi:10.7146/hjlcb.v22i42.96844.

- Cronin, Michael. 2010. “The Translation Crowd.” Revista Tradumàtica. Traducció i Tecnologies dela Informació i la Comunicació 8: 1–7. https://raco.cat/index.php/Tradumatica/article/view/225900.

- Cronin, Michael. 2013. Translation in the Digital Age. London: Routledge.

- Cronin, Michael. 2017. Eco-Translation Translation and Ecology in the Age of the Anthropocene. London: Routledge.

- Ding, Ning, Zhimiao Yang, Sida Li, and Ailing Zhang. 2021. “Where Translation Impacts: The Non-professional Community on Chinese Online Social Media – A Descriptive Case Study on the User-generated Translation Activity of Bilibili Content Creators.” Global Media and China 6 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1177/20594364211000645.

- Gambier, Yves, and Luc van Doorslaer. 2016. “Disciplinary Dialogues with Translation Studies: The Background Chapter.” In Border Crossings: Translation Studies and Other Disciplines, edited by Yves Gambier, and Luc van Doorslaer, 1–21. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gambier, Yves, and Ramunė Kasperẹ. 2021. “Changing Translation Practices and Moving Boundaries in Translation Studies.” Babel 67 (1): 36–53. doi:10.1075/babel.00204.gam.

- Hadley, James Luke, Kristiina Taivalkoski-Shilov, Carlos S. C. Teixeira, and Antonio Toral, eds. 2022. Using Technologies for Creative-Text Translation. London: Routledge.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Hebenstreit, Gernot. 2019. “Coming to Terms with Social Translation: A Terminological Approach.” Translation Studies 12 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1080/14781700.2019.1681290.

- Hermans, Theo. 2013. “What Is (Not) Translation.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Carmen Millán, and Francesca Bartrina, 75–87. London: Routledge.

- Hernández Guerrero, María José. 2020. “The Translation of Tweets in Spanish Digital Newspapers.” Perspectives 28 (3): 376–392. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2019.1609535.

- Jiménez-Crespo, Miguel A. 2017. Crowdsourcing and Online Collaborative Translations: Expanding the Limits of Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Jiménez-Crespo, Miguel A. 2020. “The Technological Turn in Translation Studies: Are We There Yet? A Transversal Cross-disciplinary Approach.” Translation Spaces 9 (2): 314–341. doi:10.1075/ts.19012.jim.

- Kaindl, Klaus. 2021. “(Literary) Translator Studies: Shaping the Field.” In Literary Translator Studies, edited by Klaus Kaindl, Waltraud Kolb, and Daniela Schlager, 1–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kress, Gunther. 2020. “Transposing Meaning: Translation in a Multimodal Semiotic Landscape.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 24–48. London: Routledge.

- Kung, Szu-Wen. 2021. Critical Theory of Technology and Actor-network Theory in the Examination of Techno-empowered Online Collaborative Translation Practice TED Talks on the Amara Subtitle Platform as a Case Study.” Babel 67 (1): 75–98. doi:10.1075/babel.00206.kun.

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Läubli, S., Sheila Castilho, Graham Neubig, Rico Sennrich, Qinlan Shen, and Antonio Toral. 2020. “A Set of Recommendations for Assessing Human-Machine Parity in Language Translation.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 67: 653–672. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2004.01694.

- Lee, Tong King. 2023. “Distribution and Translation.” Applied Linguistics Review 14 (2): 369–390. doi:10.1515/applirev-2020-0139.

- Luo, Wenyan. 2020. Translation as Actor-networking: Actors, Agencies, and Networks in the Making of Arthur Waley’s English Translation of the Chinese Journey to the West. London: Routledge.

- Marais, Kobus. 2019. A (Bio) Semiotic Theory of Translation: The Emergence of Social-cultural Reality. London: Routledge.

- McDonough Dolmaya, Julie, and María del Mar Sánchez Ramos. 2019. “Characterizing Online Social Translation.” Translation Studies 12 (2): 129–138. doi:10.1080/14781700.2019.1697736.

- Mihalache, Iulia. 2021. “Human and Non-Human Crossover: Translators Partnering with Digital Tools.” In When Translation Goes Digital: Case Studies and Critical Reflections, edited by Renée Desjardins, Claire Larsonneur, and Philippe Lacour, 19–43. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mossop, Brian. 2017. “Invariance Orientation: Identifying an Object for Translation Studies.” Translation Studies 10 (3): 329–338. doi:10.1080/14781700.2016.1170629.

- Mus, Francis. 2021. “Translation and Plurisemiotic Practices: A Brief History.” The Journal of Specialised Translation 35 (January): 2–14. https://www.jostrans.org/issue35/art_mus.php.

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2011. “Community Translation: Translation as a Social Activity and its Possible Consequences in the Advent of Web 2.0 and Beyond.” Linguistica Antverpiensia. New Series – Themes in Translation Studies 10: 11–23. doi:10.52034/lanstts.v10i.275.

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2009. “Evolution of User-generated Translation: Fansubs, Translation Hacking and Crowdsourcing.” The Journal of Internationalization and Localization 1: 94–121. doi:10.1075/jial.1.04hag.

- O’Hagan, Minako, ed. 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Technology. London: Routledge.

- Olohan, Maeve. 2014. “Why Do You Translate? Motivation to Volunteer and TED Translation.” Translation Studies 7 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1080/14781700.2013.781952.

- O’Thomas, Mark. 2017. Humanum ex Machina: Translation in the Post-global, Posthuman World.” Target 29 (2): 284–300. doi:10.1075/target.29.2.05oth.

- Pérez-González, Luis. 2020. “From the “Cinema of Attractions” to Danmu: A Multimodal-theory Analysis of Changing Subtitling Aesthetics Across Media Cultures.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 94–116. London: Routledge.

- Pérez-González, Luis, and Şebnem Susam-Saraeva. 2012. “Nonprofessionals Translating and Interpreting: Participatory and Engaged Perspectives.” The Translator 18 (2): 149–165. doi:10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506.

- Tan, Yvette, and Matt Murphy. 2022. “Shinzo Abe: Japan Ex-leader Assassinated while Giving Speech.” BBC, July 8. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62089486.

- Tymoczko, Maria. 2010. Enlarging Translation, Empowering Translators. London: Routledge.

- Tymoczko, Maria, and Edwin Gentzler, eds. 2002. Translation and Power. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- van Doorslaer, Luc. 2020. “Translation Studies: What’s in a Name?” Asia Pacific Translation and Intercultural Studies 7 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1080/23306343.2020.1824761.

- van Doorslaer, Luc, and Ton Naaijkens. 2021. “Temporal and Geographical Extensions in Translation Studies: Explaining the Background.” In The Situatedness of Translation Studies Temporal and Geographical Dynamics of Theorization, edited by Luc van Doorslaer, and Ton Naaijkens, 1–13. Leiden: Brill.

- van Vuuren, Xany Jansen. 2022. “Translation Between Non-humans and Humans.” In Translation beyond Translation Studies, edited by Kobus Marais, 219–230. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Vassallo, Clare. 2015. “What’s So “Proper” about Translation? Or Interlingual Translation and Interpretative Semiotics.” Semiotica 206: 161–179. doi:10.1515/sem-2015-0022.

- Vidal Claramonte, MªCarmen África. 2022. Translation and Contemporary Art: Transdisciplinary Encounters. New York: Routledge.

- Wang, Jing. 2019. The Other Digital China: Nonconfrontational Activism on the Social Web. London: Harvard University Press.

- Wang, Dingkun. 2022. “Chinese Translational Fandoms: Transgressing the Distributive Agency of Assemblages in Audiovisual Media.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 25 (6): 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877922110297.

- Wang, Rui. 2022. “Community-Building on Bilibili: The Social Impact of Danmu Comments.” Media and Communication 10 (2): 54–65. doi:10.17645/mac.v10i2.4996.

- Wang, Wen. 2022. “Chinese People’s Reaction to Abe’s Death Is Real.” Global Times, July 10. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202207/1270176.shtml.

- Wang, Dingkun. 2023. “Countering Political Enchantments in Digital China: With Reference to the Fan-remix Meeting Sheldon.” Translation Studies 16 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1080/14781700.2022.2067221.

- Wang, Dingkun, and Xiaochun Zhang. 2017. “Fansubbing in China: Technology-Facilitated Activism in Translation.” Target 29 (2): 301–318. doi:10.1075/target.29.2.06wan.

- White, Edward. 2022. “Callous Messages Following Abe’s Death Highlight Anti-Japanese Sentiment in China.” Financial Times, July 23. https://www.ft.com/content/7051bb56-094b-4ad5-b3df-de318bf09774.

- Wolfe, Cary. 2010. What is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Wolf, Michaela, and Alexandra Fukari, eds. 2007. Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Wongseree, Thandao. 2020. “Understanding Thai Fansubbing Practices in the Digital Era: A Network of Fans and Online Technologies in Fansubbing Communities.” Perspectives 28 (4): 539–553. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2019.1639779.

- Xu, Wei. 2022. “Xi Sends Condolences on Abe’s Death.” China Daily, July 9. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202207/09/WS62c90a99a310fd2b29e6b6e0.html.

- Yang, Guobin. 2020. “Communication as Translation: Notes toward a New Conception of Communication.” In Rethinking Media Research for Changing Societies, edited by Matthew Powers, and Adrienne Russell, 184–194. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yang, Yuhong. 2021. “Danmaku Subtitling: An Exploratory Study of a New Grassroots Translation Practice on Chinese Video-sharing Websites.” Translation Studies 14 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/14781700.2019.1664318.

- Zeng, Weixin, and Dechao Li. 2023. “Presenting China’s Image through the Translation of Comments: A Case Study of the WeChat Subscription Account of Reference News.” Perspectives 31 (2): 313–330. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2021.1960397.

- Zhang, Weiyu, and Chengting Mao. 2013. “Fan Activism Sustained and Challenged: Participatory Culture in Chinese Online Translation Communities.” Chinese Journal of Communication 6 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1080/17544750.2013.753499.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia. 2019. “From Inward to Outward: The Need for Translation Studies to Become Outward-going.” The Translator 25 (3): 256–268. doi:10.1080/13556509.2019.1654060.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia. 2022. “Online Collaborative Translation: Its Ethical, Social, and Conceptual Conditions and Consequences.” Perspectives 30 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2021.1872662.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia. 2023. “On Turns and Fashions in Translation Studies and Beyond.” Translation Studies 16 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2022.2052950.