ABSTRACT

In the face of newly emerging practices and shifting conceptual boundaries in translation and interpreting studies, the article engages with two recent theoretical proposals aiming at a reconceptualization of translation from the perspectives of semiotics and accessibility studies. The biosemiotic theory by Kobus Marais based on Peircean semiotics and Gian Maria Greco’s universalist conception of accessibility grounded in human rights are explored with reference to interpreting, and their theoretical, terminological, professional and academic implications are discussed. In addition, a conceptual mapping of various forms of media access services, including speech-to-text interpreting, serves as a basis for discussing ongoing redefinition efforts in the context of international standardization, highlighting the complex interplay of different stakeholders, including scholars, service providers, service users, and regulators.

Introduction

Enabling communication between parties speaking different languages has long been conceptualized as interpreting, with the implication that interpreting is an essentially oral form of language use. This sets it apart from the activity known as translation, generally understood to involve different written languages. Given its reliance on writing as a secondary modality of language, translation is predated by interpreting, which can therefore claim primary or primordial status. At the same time, the significance of written language in human civilization (see Ong Citation1982) has increasingly relegated interpreting to the status of a secondary concept that can be subsumed under the wider notion of translation – that is, as a concept relating to one of many different forms of translation. It is this latter view, necessarily, that underlies the present contribution to the discussion about the conceptualization of translation in translation studies. More specifically, my main goal and task will be to question current assumptions about interpreting as summarized in the first lines of this article, and to propose ways in which the concept of interpreting could or should be redefined.

As evident from my title, I see a need for rethinking and redefining the concept of interpreting. This need arises from the emergence of new social practices that are regarded or designated by some as “interpreting” but deviate from some of the concept’s defining characteristics. As some of these novel professional practices are made possible by advances in digital technology, such reconceptualization also involves the nature of human agency and meaning-making. To conduct this rethinking in a particularly broad and innovative theoretical framework, I have chosen to engage with two recent proposals that decidedly transcend commonly accepted conceptual boundaries in translation studies: the biosemiotic theory put forward by Kobus Marais (Citation2019) on the basis of Peircean semiotics and Gian Maria Greco’s (Citation2018) universalist conception of accessibility grounded in human rights.

Before entering into the conceptual discussion, I reflect on my positionality in this endeavour in order to set the stage for subsequent arguments about wider social dynamics and professional implications. This meta-level reflection on stakeholder perspectives will be the subject of the following section. Subsequent sections are then devoted to the state of the art (“interpreting as we know it”) and to the way in which two recent scholarly proposals (Greco Citation2018 and Marais Citation2019), on the one hand, and novel social practices, on the other, have come to challenge widely held conceptualizations. Using the example of speech-to-text interpreting, I highlight the conceptual debate among stakeholders and then discuss the implications of a redrawing of conceptual boundaries for the profession and the academic discipline.

Perspectives

Scholars and (other) stakeholders

Working within the scholarly community of an academic discipline, there is generally no need to explain or justify why one would want to question or reconsider the concepts established for one’s object or field of study. Rather, such (re-)thinking would be regarded as the scholar’s main task, if not primary responsibility. Less so, perhaps, in a “human science” and empirical discipline (Pöchhacker Citation2011) like interpreting studies, which owes its existence to a previously emerged social practice that involves a set of stakeholder groups with their own legitimate interests. Specifically, the two groups most immediately involved in interpreting practices are the providers of interpreting services, on the one hand, and the users of such services, on the other. Each of these stakeholder positions can be analysed more closely and allows for relevant distinctions. Providers can be conceived of as individuals with the necessary qualifications, as agencies providing such services, or indeed as “the profession”, which can in turn be broken down into different professional domains, such as international conference interpreting and community interpreting. Users can in turn be broken down in various ways and thought of as individuals or groups with specific communication needs but also as client organizations commissioning interpreting services.

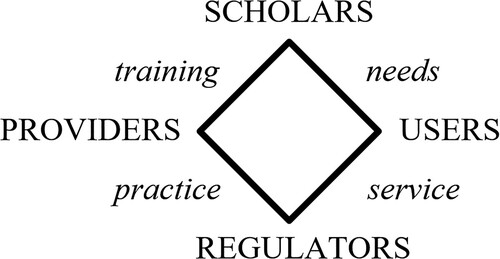

Beyond the set of relations holding between providers and users, each of the two principal stakeholders may be linked to the position of scholars in various ways (see ). Examples typical of the field of interpreting include academics who serve as trainers of future professionals and, conversely, practitioners who are also engaged in academic training and research. For these and other, more practical reasons, the relationship between the positions of scholars and service providers tends to be much closer than that between scholars and users, which typically finds expression in reception research on user needs and expectations.

A stakeholder position with particular potential to shape the social practices in question is that of a policy-maker, which I suggest could be labelled here as a “regulator”, in a broader sense. This could include any institution or organization issuing guidance, legal provisions or standards regulating the social practice in question. In the field of legal interpreting, for instance, this would include the lawmakers adopting legislation governing who can serve as an interpreter in court, or the fees to be paid for such service; in healthcare, this could be an individual hospital issuing a policy banning the use of children as interpreters.

Even more so than the other positions depicted in , the role of regulators can be instantiated by a variety of social agents, some of which may pertain also – or mainly – to the other stakeholder groups. Examples include an association of the Deaf issuing a code of conduct for signed language interpreters, and scholars intent on redefining the nature and scope of professional service provision, as is the case with the present article.

Positionality

In the framework of the above sketch of stakeholder relations, I can characterize my positionality as that of a scholar of interpreting who is also engaged in interpreter education. More specifically, my scholarly stance favours reaffirming the specificity of interpreting within the broader field of translation studies as well as vis-à-vis related disciplines. This position is undoubtedly shaped to a considerable extent by my professional training and experience as a conference and media interpreter and my membership of an association representing the interests of the interpreting profession. As an interpreter educator, on the other hand, my interest lies in ensuring that graduates can find gainful employment thanks to the professional (and academic) competence developed while working toward their Master’s degree. More broadly, I am committed, as a scholar and as a trainer of future service providers, to the viability of interpreting as a profession – as long as a case can still be made for the need for this profession in society.

As a scholar and educator (and former professional), I cannot claim any persistent direct relation with the service-user position; I can merely endeavour to be mindful of user needs and interests indirectly, by working toward the availability of the professional services required. A more direct route would be empirical reception studies, but this is not the task defined for this theoretical article. Another indirect route consists in providing regulators with theoretical arguments that can serve to define and specify the nature of the service, and this is indeed one of the purposes that this article is intended to serve.

Language

Beyond my affiliation with the academic field of interpreting (and translation) studies, my epistemic perspective is constrained in significant ways by my linguistic repertoire as a native speaker of German engaged in a debate that is conducted in English as the dominant vehicle of scholarly communication. Given the importance of terminology in this endeavour, issues of language acquire particular complexity, all the more so since some of the social practices under study are variously perceived and labelled in their respective linguistic and cultural context.

My limited linguistic horizon, which unavoidably amounts to a “Western” – and a European – perspective, is thus a further aspect of my positionality that shapes my attempt at (re)definition. As Klaus Kaindl (Citation2020, 53) reminds us, definitions “are not neutral, innocent acts, but attempts to ‘discipline’ an object of research, which [are] always guided by particular interests”.

Conceptions

In line with the inclusion of the present reflections in the broader debate about the conceptualization of translation in translation studies, the basic idea about interpreting, or supermeme (Pöchhacker Citation2022a, 58), is that it is a form of translational activity, or “Translation” with a capital “T” to indicate its status as a superordinate term. While this obviates the need to define interpreting “from scratch”, it makes interpreting scholars dependent on the conceptualizations of those who would define translation in general. For instance, in the German school of functionalist translation theory (for an overview, see Martín de León Citation2020), Translation (including interpreting) might be defined as interlingual text production with the aim of fulfilling a specified communicative purpose, whereas in Gideon Toury’s (Citation2012) attempt to avoid fixing conceptual boundaries a priori, interpreting (as any translation) would be whatever is presented or regarded as such in a particular place at a given point in time (see Toury Citation2012, 27). These conceptual approaches will be complemented below with more recent definitional proposals. First, however, I will summarize what many would regard as a highly stable conception of interpreting within translation studies.

Interpreting as we know it

Taking as point of departure the assumption of translation as an interlingual text-processing activity in which a source-language “text” (in any linguistic modality) is transformed into a target-language text fulfilling certain requirements, Otto Kade (Citation1968) distinguishes interpreting from translation on account of its immediacy, in the temporal sense: the source text is presented or available only once, and the target text is produced “here and now”, in real time, and therefore not available for reviewing or revision (see Pöchhacker Citation2022a, 11). Although Kade affirms that the source text in interpreting is “typically oral”, his early definition is open toward other linguistic modalities and accommodates the real-time rendering of a written text as well as interpreting from, into or between signed languages.

The full potential of Kade’s definition was not evident at the time, as interpreting was seen as an essentially oral activity that was practiced for thousands of years before it was propelled to professional recognition around the mid-twentieth century, when the original “consecutive” mode of target-language re-expression was joined and largely displaced by its simultaneous variant. Regardless of the institutional settings in which interpreting came to proliferate toward the end of the twentieth century, it remained a stable concept, characterized as “an activity in which a bilingual individual enables communication between users of two different languages by immediately providing a faithful [oral] rendering of what has been said.” (Pöchhacker Citation2019, 46).

Over the past few decades, the (professional) practice of interpreting has undergone several “shifts” (Pöchhacker Citation2022b) that have softened some of the previously solid conceptual boundaries. For one, interpreting in the signed modality of language has become acknowledged on a par with the oral-aural route of mediated communication. This integration is reflected in academic reference volumes (e.g. Pöchhacker Citation2015a) as well as general standards for interpreting services (ISO Citation2019). Moreover, the use of digital technologies to support the interpreting process and to enable the delivery of interpreting services has given rise to new forms of professional practice, leading some to claim a “technological turn” (Fantinuoli Citation2018) with profound impacts on working conditions and delivery modes. Nevertheless, the conceptual implications of technology use have been relatively minor and mainly relate to the defining characteristic of immediacy: the use of digital recording in such working modes as simultaneous consecutive (Pöchhacker Citation2015b) and previewed TV news interpreting (Tsuruta Citation2015) has relaxed the criterion of temporal immediacy, and video-mediated remote interpreting (Braun Citation2015) has eliminated the traditional spatial constraints on interpreter-mediated communication. Interpreting is no longer limited to a performance “here and now”, but the conception of interlingual processing by human agents with proficiency in two different (spoken or signed) languages has remained intact.

Moving boundaries

More severe challenges to the traditional conception of interpreting have come from the emergence of new forms of practice featuring novel manifestations of language and linguistic modality. As presented and illustrated more extensively elsewhere (Pöchhacker Citation2019), inter- and intralingual processing are variously combined with intra- and intermodal language use to yield such types of translational performance as Deaf interpreting (from a written text or another interpreter’s signed rendering) and live subtitling. The latter, in particular, has become prominent in recent decades in connection with the high demand for prepared subtitles for deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers, also known as SDH. What Deaf (relay) interpreting and live subtitling have in common is that they are typically done intralingually, within the same signed language and spoken/written language, respectively. Since these translational activities are intralingual, those providing such services do not necessarily need to be proficient in more than one language.

Moreover, most producers of SDH for media broadcasts have come to rely on respeaking with speech recognition software (Romero-Fresco Citation2015, Citation2019), making this a human performance that is crucially dependent on digital technology. Given the rapid progress of speech (recognition) technologies over the past decade, the respeaking component of live subtitling has increasingly been replaced by fully automatic (speaker-independent) speech recognition, moving this machine-assisted or machine-driven process toward a largely automatic one in which human agency is required only for (live) editing.

A more automation-resistant form of human media-content processing that is equally monolingual and intermodal is live audio description (AD). Unlike (intralingual) live subtitling, however, which encompasses two modalities of the same language, spoken and written, live AD involves the semiotic (sub)mode of moving images as well as the spoken modality of language.

These examples of less typical translational activities, which nevertheless retain such defining features of interpreting as real-time performance and simultaneous processing, go beyond the long-established conceptual boundaries of interpreting and constitute ample grounds to search for new approaches to conceptualization. Such new avenues have recently been opened up by scholars in translation studies and related fields, and I will examine two of these proposals for redefining what used to be understood as translation (and interpreting).

Redefinitions

Before engaging with the more far-reaching recent conceptual proposals, I would also like to consider the case against the need for redefinition. One might contend that, with regard to intralinguality, intermodality and automation, the early proposals by Roman Jakobson (Citation1959) and James Holmes (Citation1972) could be relied on to obviate the need for a broadening of definitional boundaries. After all, Jakobson (Citation1959, 233) asserted that translation (and interpreting) could also be “intralingual” and “intersemiotic”, and Holmes (Citation1972) made allowance for translation by machine in his “medium-restricted” theoretical domain. While Jakobson’s tripartite division has been referred to quite frequently in recent years, it has also been criticized (e.g. by Toury Citation1986) for prioritizing language (without reference to its nonverbal components) and making the distinction between intra- and interlingual at the same level as that between language and other semiotic modalities. The strict separation between human and machine translation in Holmes’s (Citation1972) taxonomy, on the other hand, makes it difficult to account for translation (and interpreting) processes in which human agency and artificial intelligence are variously combined in compound workflows.

Efforts to give translation a broader and more solid theoretical foundation have centred on the semiotic dimension, which has gained renewed prominence in the twenty-first century thanks to the notion of multimodality (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2001) and the theory of social semiotics. This “semiotisation”, in the sense of disciplinary orientation, has been pursued in particular by Marais (Citation2019) in his (bio)semiotic theory of translation. As will become clear, and as found already in Jakobson’s (Citation1959, 233) wording of “translation” being “an interpretation of verbal signs”, the semiotic account tends to raise special terminological challenges for the notion of interpreting.

Translation and interpreting as meaning-making

Taking a deductive approach rather than relying inductively on what is labelled as translation, Marais (Citation2019, 7) aims at “the broadest possible conceptualization of translation” and focuses on the processes of “producing and interpreting signs” (5) beyond the bounds of language and the human species. Revisiting Jakobson’s (Citation1959) definitions, he goes back to their foundations in Peircean semiotics, in which translation is used as the technical term for the triadic semiotic process which relates an object, a sign representing it, and the meaning afforded by that sign, to one another. In this conception, “translation relates to the process of creating meaning”, and the “outcome” of the perceptual and analytical processes that (inter)relate sign and object is an “interpretation” (Marais Citation2019, 104).

Noting the conceptual proximity of “translation” and “interpreting”, Marais acknowledges a degree of fuzziness in Peircean thought when the two terms are used interchangeably. Elsewhere, before defining translation as creating meaning, he himself equates “interpreting” with “understanding” (Citation2019, 55). Most strikingly, though, considering the many anecdotal references to interpreting (in refugee, religious and other public service settings) in an earlier chapter his book, Marais chooses to ignore what he calls “the dictionary use of ‘interpretation’ or ‘interpreting’ for oral translation”, relegating it to a footnote that characterizes it as an unwelcome complication (Citation2019, 82).

Irrespective of the innovative potential of Marais’s (Citation2019) comprehensive theoretical framework (see Marais Citation2022), his semiotic reconceptualization of translation without reference to “interpreting as we know it” might seem to have little relevance for the present discussion – unless one were to tweak the Peircean account by prioritizing interpreting rather than translation. Embracing the view that interpreting relates to the process of meaning-making and results in an interpretation (understanding), one can propose a (bio)semiotic theory of interpreting in analogy to the theoretical framework of Marais (Citation2019).

Mindful of the unbounded scope of Marais’s (Citation2019) theory of translation, my analogous proposal for interpreting equally centres on a generic semiotic process that is based on the interrelations between an object (of perception), a sign in some semiotic mode(s) and the interpretation derived from them. It is assumed to apply to any semiotic modality and mode of sensory perception by some form of living organism interacting with an environment. Beyond the most fundamental bio-cognitive level, the focus could be set to interaction between different species and then also to the level of literally specific interaction – that is, specific to a given species (see Marais Citation2019, 71, 78). Concerns about anthropocentrism notwithstanding, one might choose to focus on meaning-making processes by and among humans and thus apply the biosemiotic conception in the framework of human communication. Under this heading, a relevant distinction can be made between receptive (“meaning-taking”) and productive processes (“meaning-making”), typically involving some sort of sign or mode of semiotic resources.

Marais (Citation2019, 142) derives three categories of translation from the components of the semiotic process, depending on whether there is a change to the sign (“representamen”), to the object or to the representation (“interpretant”). As he acknowledges, “Translation of the representamen [is] what is currently studied in translation studies, adaptation studies, multimodality studies, and multimedia studies” (Citation2019, 146). Marais goes on to distinguish subcategories of representamen translation with regard to sensory modalities (“visual, aural, tactile, olfactory, gustatory”), which points to the notion of semiotic modes in current multimodal accounts of translation (e.g. Kaindl Citation2020) and interpreting (e.g. Pöchhacker Citation2021).

In order to connect the general biosemiotic theory of interpreting to the specific conception of translation (and interpreting) as multimodal text processing, the scope needs to be narrowed to the human species, and hence to human language and communication. Maintaining the term “interpreting” also for the focus on the generic representamen, the term “translation” could finally be introduced when the sign (representamen) is conceived of as a (multimodal) text. At this more specific level of theorization, translation scholars can, for instance, rely on Kaindl (Citation2020, 58) for an understanding of translation as “a conventionalised cultural interaction in which a mediator transfers texts in terms of mode, medium, and genre across semiotic and cultural barriers for a new target audience”. While one might take issue with the transfer metaphor in this formulation and opt for terms like “reconstitution” (Carreres and Noriega-Sánchez Citation2020, 198) or “transposition” (Kress Citation2020), this kind of generic definition of translation can serve as a broad foundation for distinguishing relevant subcategories of “translation as we know it”. The question here will be whether or in what way the notion of “interpreting as we know it” – that is, interpreting in the translational sense – is still needed and useful.

Translation, interpreting and access

Whereas the key terms in Marais’s (Citation2019) biosemiotic theory of translation and my interpreting-based analogue are not used in a metaphoric sense, the discussion in this section could be said to hinge on metaphor. A most appropriate cue and link is the notion of “barriers” in Kaindl’s (Citation2020) definition above. A barrier is defined as something that blocks movement or hinders access. Literally as well as metaphorically, a barrier is a hindrance or obstacle to be overcome, as in the well-worn expression “overcoming language barriers”. Germane to the idea of multimodality and the theorizing done above, Kaindl’s definition speaks of “semiotic barriers”, which might be construed as blocking access to meaning as a result of linguistic and sensory (perceptual) barriers alike.

The focus on access across sensory barriers came to the fore early in the millennium when the rights of persons with disabilities were at last enshrined in a world-wide convention (United Nations Citation2006). Access to media content emerged as a core area of what came to be referred to as “accessibility”, and it was scholars of audiovisual translation (AVT) who took an interest in such access services as SDH (closed captioning), which had been pioneered by broadcasters in the US and the UK decades earlier. Jorge Díaz Cintas, Pilar Orero and Aline Remael (Citation2007, 13) suggest that “accessibility […] can be compared, to a certain extent, to translation and interpreting”, arguing that as translation allows access to publications and the written heritage, interpreting permits access, for instance, to conference speeches, healthcare consultations and live media broadcasts. They go on to note the expansion of the field of AVT by “new professional translation processes” (Citation2007, 11) such as the live subtitling of TV programmes using speech technologies, and audio description. These AVT scholars evidently embrace both intralingual and intermodal forms of translation (and interpreting) alongside the established forms of interlingual translation in the media (i.e. prepared subtitling and dubbing).

As regards interpreting, it must be noted here that when the topic of language transfer in audio-visual communication came to attract widespread scholarly attention in the mid-1990s, interpreting in the media had considerable visibility – despite a rather narrow focus on media interpreting in spoken languages (e.g. Translatio Citation199Citation5). Its scope expanded with the emergence of signed language interpreting of live media broadcasts, and Yves Gambier (Citation2003) drew up a comprehensive list of “types of AVT” that included various forms of translation as well as interpreting. What is more, he complemented the “dominant” forms of AVT – including interlingual subtitling and dubbing but also interpreting in different modes and modalities – with “challenging” ones such as “live or real-time subtitling”. Some two decades later, however, the status of (media) interpreting in the field of AVT has become highly uncertain. In the Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation (Pérez-González Citation2019), for instance, there is not a single mention of the term “media interpreting” in the entire 571-page volume, and the three occurrences of “interpreting” listed in the book’s index refer mainly to respeaking. Nor does media interpreting fare much better in a similar and even more voluminous anthology published by Palgrave (Bogucki and Deckert Citation2020). It appears from these reference volumes that AVT has been reconceived as translation in the narrower sense (with a lower-case “t”), no longer including interpreting. At the same time, AVT has been complemented by media accessibility (MA), which was originally claimed as a subfield of AVT (e.g. Orero Citation2004: viii) but is now often juxtaposed with it. This is reflected in the title of the Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility (Bogucki and Deckert Citation2020), whose introductory chapter leaves the relationship between the two largely unspecified (see Deckert Citation2020, 3).

In a far-reaching deductive account grounded in human rights, Greco (Citation2018) points to the vast scope of access issues that have attracted researchers from many different fields, among whom translation scholars are but a small group. While acknowledging that MA was “born and bred” within the field of (audiovisual) translation studies, Greco argues that MA needs to break free of the bounds of translation and find its rightful place in accessibility studies. The main reason for his dissatisfaction with AVT as a home to MA is the “particularist” focus on sensory and linguistic barriers: “children, the elderly, and persons with cognitive disabilities, for example, as well as any service that makes media artefacts accessible to them, are thus excluded from the visible horizon of MA” (Citation2018, 218). Greco therefore concludes that “MA is wider than AVT and cannot be merely reduced to a sub-area of TS [translation studies]. It is a broader, interdisciplinary area[] that criss-crosses many well-established fields, including translation studies and AVT” (218).

Greco’s view of disciplinary overlap and stratification opens up new perspectives but remains vague when it comes to specific conceptual relationships. Leaving aside his juxtaposition of translation studies and AVT, it remains unclear, for instance, whether a service such as live subtitling should still be considered a form of AVT and whether AVT would be regarded as a sub-area of translation studies or accessibility studies, or both. Most importantly for the present discussion, one might ask whether live subtitling would be defined as a form of interpreting. If so, and considering that interpreting has been displaced from AVT, would such interpreting still be part of translation studies or would it be conceived of as a “media accessibility service”?

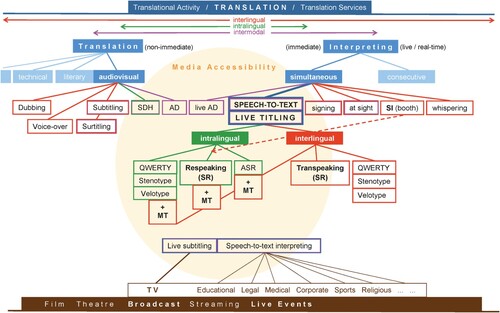

Questions like these prompted a joint effort at conceptual mapping within the EU-funded project ILSA (Interlingual Live Subtitling for Access) completed in 2020 (ILSA Citation2020). The map, finalized by Pablo Romero-Fresco and myself, is reproduced as and is intended to highlight some of the conceptual and terminological issues under discussion.

The map depicted in is meant to account for translational activities in the broader sense, as commonly defined within translation studies. In terms of the biosemiotic theory, this corresponds to the level of representamen interpreting, or translation. In a multimodal account, it refers to the reconstitution of a complex sign that amounts to the re-expression of meaning based on understanding and therefore constitutes a multiple process of meaning-making. Reading the map from top to bottom, it is important to note that translation extends along the interlingual and intralingual as well as the intermodal dimension, colour-coded as red, green and purple, respectively. The top-level taxonomic distinction, based on the criterion of immediacy, or live performance and use, is between translation, on the one hand, and interpreting, on the other. In the area of translation, shown on the left-hand side, AVT is foregrounded as one of many areas of translation, of which only few are listed, for reasons of space. In contrast, the area of interpreting, shown on the right-hand side, is subcategorized by temporal working mode rather than genre or setting.

The subtypes branching out from the foregrounded (sub)forms – audio-visual translation and simultaneous interpreting – are positioned in such a way as to move from interlingual ones in the outer areas toward intralingual and intermodal ones in the centre. Four-and-a-half types of translational activity are found in the conceptual space of media accessibility, indicated as a creme-coloured sphere. These include SDH and AD as subtypes of AVT and different kinds of simultaneous interpreting processes: live AD, “live titling” (speech-to-text) and, to some extent, interpreting into signed language (“signing”), which is not limited to media settings or the voice-to-sign mode.

As indicated by the dark-blue line and boxes, the focus in this map is on what is designated, somewhat inconsistently, as “speech-to-text” together with the neologism “live titling” (Pöchhacker and Remael Citation2019). The main inconsistency here, aside from the rather casual labelling of simultaneous interpreting forms to the right, is that “speech-to-text” serves as a generic label for intermodal processes that can be intra- and interlingual alike. It is only in the lower part of the diagram that current labels – and settings – for such activities (“live subtitling”, “speech-to-text interpreting”) are mentioned, associated with the generic label by the dark-blue box.

In the centre of the diagram, the two variants of live titling, shown in green and in red, are analysed further with regard to production technique and technology use. What is evident – and significant – here is that all forms of live titling use some form of technology, from computer keyboards to machine translation (MT). The diagram also shows that live titling is mainly done using speech recognition (SR) technologies and that both its intralingual and its interlingual form can be accomplished by a human agent (using SR) or be fully automatic. (In the variant shown with a broken red line, interlingual live titles are created by respeaking of a simultaneous interpretation produced by a spoken-language interpreter from a booth.)

In addition to highlighting the role of digital technologies, the map is intended to show, with some regrettable inconsistencies, how various forms of translation and interpreting, produced with specific techniques and human skills as well as technologies, are employed to provide access to media content. These types of translation and interpreting can therefore be seen as serving media accessibility. At the same time, they are also practiced beyond media settings, as mentioned above for signed language interpreting and as indicated by the elements lying partly outside the sphere of media accessibility. (This applies equally to intralingual speech-to-text interpreting but is not shown for the elements in green due to graphic constraints.)

From speech to text

Based on the map described above, it seems superfluous to discuss the redefinition of interpreting under yet another heading. accounts for interpreting as a form of translation (“as we know it”) in and between any linguistic modalities as well as for transmodal semiotic processes such as rendering (moving) images as speech. Simultaneous speech-to-text processing emerged clearly and cleanly from the taxonomy as a form of interpreting. And yet it cannot be defined as such in international standards.

Having engaged with scholarly proposals for the reconceptualization of translation and interpreting, my aim in the present section is to extend, or bring down, the discussion to the position of regulators as shown in . The regulatory body in this case is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), more specifically, its technical committee (TC) number 37 on language and terminology. TC 37, whose official remit is “Terminology and other language and content resources”, has five subcommittees, the fifth of which (SC5) is devoted to “translation, interpreting and related technology”. The list of some two dozen standards drafted and published by SC5 ranges from the specifications for interpreting booths (ISO 2603 and 4043) to general and setting-specific “requirements” for interpreting services (e.g. ISO 18841, 13611, 20228, 21998, 23155) and to technical specifications for simultaneous interpreting delivery platforms (SIDPs) (ISO 24019). It was in connection with work on the SIDP standard for distance interpreting that the inclusion of speech-to-text interpreting (STTI) was discussed, as this form of simultaneous interpreting can also be delivered in distance mode. As it happened, STTI could not be accommodated in the published standard (ISO Citation2022) because it does not fit the definition of interpreting in the TC37 framework of standards. What, then, is interpreting, for the purposes of standards adopted by SC5?

In ISO 20539, the “vocabulary” standard of SC5 that underlies all ISO translation and interpreting standards, “interpreting” or “interpretation” is defined under item 3.1.10 as “rendering spoken or signed information from a source language […] to a target language […] in oral or signed form” (ISO Citation2019). Thus, this main part of the definition is concerned solely with the “linguality” (Pöchhacker Citation2019, 47) of interpreting, without any explicit reference to translation nor to the process-related features that would set the two apart. Without considering other semiotic modes, the definition merely specifies the applicable linguistic modalities (spoken and signed) and reaffirms the criterion of interlinguality (“from one language to another”). Not surprisingly, the definition of translation (item 3.1.8) takes the same approach, specifying the target-language form as “written”. However, translation is also envisaged into signed language, accommodating signed language translation from a written text. In fact, the standard also includes an entry for “sight translation” (3.4.16), defined as “rendering written source language content” in the form of spoken or signed language (ISO Citation2019). The fact that this item is listed under the heading of “concepts relating to interpreting” as well as the addition of “sight interpreting” as a synonym in related documents strongly suggest that interpreting as defined in ISO 20539 does accommodate the written modality of language. According to ISO standards, interpreting can be “text-to-speech”; it just cannot be “speech-to-text”.

It bears repeating that the ISO definitions, which are derived from a consensus-building process involving a range of different stakeholders, do not distinguish between translation and interpreting on the basis of process-related features, such as immediacy or real-time performance. The only condition set in the remainder of the definition for interpreting is “conveying both the language register […] and meaning of the source language content” (ISO Citation2019). Rather strikingly, however, this sort of “fidelity” requirement for interpreting is conspicuously absent from the definition of translation. In fact, the two occurrences of the word “meaning” in the definitions of “interpret” (3.1.9) and “interpreting/interpretation” (3.1.10) are the only ones in the entire ISO document on the basic concepts and vocabulary of translation and interpreting. More puzzling is the fact that “meaning” is practically the only term for which there is no reference to a definition (as dealt with by bracketed omissions in the quotations above). However unwittingly, the standard appears to highlight that interpreting, more so than translation, is inextricably bound up with meaning.

Implications

Having explored ways of (re)defining and reconceptualizing interpreting from very different perspectives, the present section will seek to integrate the various insights and theoretical options in a discussion that would ideally lead to an enriched understanding of the concept of interpreting and an awareness of the implications of one stance or another for the interpreting profession(s) and for interpreting (and translation) studies as a discipline. As in the previous section, I will proceed from the scholarly perspective to the down-to-earth concerns of communication-service stakeholders, and from the wider theoretical framework to specific social needs and practices.

Interpreting as meaning-making

In the face of the sometimes interchangeable use of “translation” and “interpretation” in Peirce’s theory of semiotic processes, I have followed Marais (Citation2019, 60) in “assign[ing] technical meanings to these terms within the field of translation studies” and suggested, all too casually perhaps, to prioritize “interpreting” over “translation” at the most general, (bio)semiotic level of analysis. This has a number of conceptual, terminological and disciplinary implications.

Building on semiotic theory makes the notion of interpreting “visible” in different dimensions within a single integrated conception. Though not used in a metaphorical sense as profusely as translation (e.g. Zwischenberger Citation2017), interpreting/interpretation has a fundamentally “hermeneutic” dimension – as in “interpretation (understanding)” (Marais Citation2019, 55) – that can establish common ground for apparently disparate professional activities. In this sense, a relative or next of kin that has been completely ignored in interpreting studies to date is heritage interpretation, an educational activity in which an individual with special training helps visitors understand and appreciate a particular site, such as a park or a museum. The academic foundations of this practice are evident from the fact that the Journal of Interpretation Research has been published, by Sage, for more than a quarter-century (Powell and Stern Citation2021).

In the field of interpreting studies, the conception of interpreting as meaning-making obviously connects directly with the meme of making sense (Pöchhacker Citation2022a, 61–62) that lies at the heart of the “interpretive approach” to translation and interpreting (Salama-Carr Citation2009) championed by the “Paris School” (Lederer Citation2015). On the other hand, foregrounding the theoretical (semiotic, hermeneutic) sense of interpreting alongside with its conception as a more or less professional social practice carries the risk of making the concept all too fluid to ensure effective technical communication. A radical solution for this would be to invert previous usage and largely reserve the term “interpreting” for the general theoretical level and replace it with a synonym when referring to the practice of enabling communication in real time. At the level of translation as specified above, an appropriate label for interpreting could be “live translation”. The qualifier “live” can be assumed to be readily understood in today’s strongly mediatized culture (e.g. Hjarvard Citation2013) and covers such welcome semantic traits as real-time co-present performance and direct broadcasting at the time of production (Merriam-Webster Citation2022). In an equally relevant sense, “live” refers to production and reception at the same time and lends itself very well to foregrounding the user perspective, not least in relation to an understanding of live translation as a communication access service that consists in re-expression for immediate use.

(Live) translation for access

Greco’s (Citation2018) universalist account of accessibility has special appeal for its fundamental grounding in human rights and the notion of access as a requirement for enjoying these rights and safeguarding human dignity. His approach to media accessibility from what he envisages as the interdisciplinary field of accessibility studies moves the users of such services, including translation services, centre-stage. It aspires to eliminate what Greco identifies as a persistent “maker–user gap” which results from the design and provision of services “according to the makers’ interpretation of users’ needs and capabilities” (Citation2018, 212). Nevertheless, regulatory efforts for access services must necessarily encompass the maker and user perspectives alike. This is evident from the European Accessibility Act (European Union Citation2019), which first and foremost seeks to harmonize accessibility requirements for products and services so as to ensure the proper functioning of the internal market. Although building on the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations Citation2006), Paragraph (1) of the Directive’s preamble speaks of “barriers” not to equal participation in society but “to the free movement of certain accessible products and services”. The preamble goes on to mention also “barriers to accessing content” (41) faced by persons with disabilities, but it is only in Section IV of Annex I that specific accessibility requirements are formulated. Paragraph (b)(ii) specifies technical quality requirements for audio-visual media “access services […] such as subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing, audio description, spoken subtitles and sign language interpretation”. It remains unclear whether the first two forms of access service in the list are to be understood in the broader sense, in each case including non-immediate as well as live production (i.e. audio-visual translation and simultaneous interpreting as mapped in ), or whether they are in fact limited to AVT with a lower-case “t”, so that the Directive would fail to direct media service providers to provide also for live translation.

Since Article 3 (Definitions) is limited to the same exemplary enumeration, the Directive fails to provide a full description or even mapping of access services to ensure media accessibility, let alone their characterization as translation-based or not (see Greco and Jankowska Citation2020) or as provided live or not. It will be up to legislators in EU member states to adopt the necessary legal provisions in yet another example of regulatory efforts in which the result will be determined by the variable interplay of stakeholder interests and contributions. It is doubtful that scholars (and their academic publications) will play a leading role in this endeavour, just like they appear to have little impact on the (re)drafting of international standards regarding translation and interpreting services, which, ideally, could be incorporated into legislation by way of reference and thus become even legally binding.

Conflicting views of scholars on the one hand and regulators on the other are part and parcel of the interrelations depicted in and, under propitious circumstances, can lead to a newly negotiated consensus. The challenge involved can be demonstrated by considering the European Directive in relation to Greco’s (Citation2018) universalist conception of accessibility. While acknowledging in its preamble that persons other than those with disabilities, such as the elderly, can also benefit from accessibility services (4), the Accessibility Act is clearly particularist, in Greco’s (Citation2018) terms, whereas the notion of universal accessibility demands “access for all”, whatever the reason(s) for not being able to fully access (media) products and services.

The universalist conception of accessibility thus clashes with regulations targeting particular groups, such as persons with sensory impairments or even those facing linguistic barriers. Moreover, it has relevant theoretical implications. While Greco (Citation2018) considers audio-visual translation and interpreting too narrow to sustain media accessibility, the universalist demand that media products need to be made accessible to any audience not capable of fully accessing them “in their original form” (Greco Citation2018, 211) implies that this could be achieved largely or even particularly through translation, defined as reconstituting (multimodal) texts “for a new target audience” (Kaindl Citation2020, 58). Greco may have a point when it comes to such technology-based access techniques as clean audio (Jankowska Citation2020), even though such signal reprocessing to make audio content more understandable might also be seen as a process of semiotic change; however, the role of translation extends to many more walks of life than media services, so that it seems misguided to relativize the role of translation, whether live or not, as a service to provide access for all to information and communication of any kind. After all, it is for translational activities that most societies have developed an institutional infrastructure devoted to the training of professional communication (access) service providers. Greco (Citation2018, 216) points to ongoing efforts by MA scholars to respond to educational needs for providers of MA services, but it is not clear that these would (need to) be essentially distinct from current training opportunities in AVT and signed- as well as spoken-language interpreting.

Translation machines and (human) interpreters

My final set of reflections here relates not to the processes and services under discussion but to the agents by whom, or by which, they are performed (see also Olohan Citation2011). This is evidently connected with the training issues mentioned above, particularly when it comes to labels for distinct professional identities, but it applies to the general theoretical level as well.

In the biosemiotic conception, there is little need to dwell on the justification for designating any meaning-maker as an interpreter. Given the ubiquity of semiotic processes in the way living organisms interact with their environment, there are at least as many interpreters as there are signs. More controversially, one might even lift the restriction of the theory to biosemiotics and extend its scope to include such sign transformation processes as the conversion of high-level programming language (source code) into machine-readable processing instructions (machine code) while the programme is being executed. The computer programme accomplishing this is called an interpreter (e.g. Marciniak Citation2002) – in other words, an interpreter is a computer programme.

Without carrying the beyond-bio argument too far, the reference to software engineering serves to highlight two points of great relevance to the present discussion: translation (representamen interpreting) can be done by machine, and such sign processing can be done while the response processes are carried out. More pointedly, machine translation of this sort, or indeed of any sort, can be construed as simultaneous interpreting.

Before returning to this issue, I will pursue the topic of agent labels also within the second major theoretical proposal featured in this paper. Anchoring his deductive reasoning not in semiotics but in accessibility, Greco (Citation2018) makes a highly original proposal for designating the providers of user-oriented access services. With reference to Otto (and Marie) Neurath, the creator(s) of Isotype, a pictorial language devised some 100 years ago as the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics, he finds the origins of the “accessibility expert” in the role of “transformer” (Citation2018, 221). In this account, the transformer, as part of an interdisciplinary team, is the expert capable of understanding the source data, deciding what to transmit and how to make the content understandable by expressing it with non-verbal semiotic resources. Here again, the notion of making information accessible is germane to Kaindl’s definition of translation as multimodal text processing in any “mode, medium, and genre across semiotic and cultural barriers” (Citation2020, 58).

The term “transformer” is akin to “translator” but foregrounds the semiotic (sign-form) dimension of the process. Alternative terms for the process of semiotic reconstitution, such as transposition (Kress Citation2020), resemiotization (Iedema Citation2003) or simply re-expression, are not as easily turned into labels for the agent role. Moreover, any of these options would seem highly generic and unspecified compared to the role of translator. Such vagueness would be problematic at the level of social practices, including communication access services, where provider–user relations are founded on well-defined expectations that can generate professional trust. Laying down the competence requirements and recommended professional practices is crucial to immediate-stakeholder relations, and research-informed curricula are as vital to achieving this goal as are regulatory efforts such as the adoption of standards.

Recalling the definitional incongruities discussed in relation to current ISO standards, the issue of appropriate labels for agent roles must again be referred back to the quadrangular interplay of stakeholders as depicted in . Scholarly proposals must be acceptable to service providers and meaningful to users, and both immediate stakeholder groups as well as scholars would ideally partake in regulatory efforts such as the drafting of international standards defining (communication access) services and the requirements for providing them at a specified level of quality (accessibility).

In the specific case of STTI, the standard-setting process remains heavily biased in favour of the service provider perspective, with limited input from scholars (not least for lack of research findings on user reception) and little, if any, representation of service-user interests. In addition to the wide “maker–user gap” (Greco Citation2018, 212), there are also rifts among different service-provider groups, such as spoken-language conference interpreters, live sub-titlers (respeakers) and technology companies offering access services by machine. Such conflicts of interest, particularly between human and automated service provision, take this discussion back to the human–machine relations featured in the title of this section. There is no space here for an extensive discussion of this complex topic, so I will end these reflections with a final conceptual and terminological proposal.

Most forms of translation (“translation as we know it”) nowadays involve the use of digital language-processing technologies, if not some form of machine-translation engine, and it is a truism that an ever-increasing share of translations is produced in part or solely by machines drawing on previously recorded translation solutions. The definitional challenge, therefore, arises not from translators working with machines but from machines working essentially without human agency. The Congress of the European Society for Translation Studies (EST) held in Oslo in June 2022 devoted an entire thematic session to the question “Is machine translation translation?” The analogous question here is whether real-time or live translation by machine (“machine interpreting”) is interpreting. I would suggest that the biosemiotic theoretical framework as well as the distinctly user-oriented approach from accessibility offer some grounds for questioning the capability of machines to engage in target-oriented meaning-making. Having made interpreting as meaning-making the centre of its conceptualization, it seems better justified to claim that human (i.e. embodied and situated) live translation is conceptually distinct from non-human automated sign manipulation. I therefore propose to acknowledge that live translation can be accomplished by humans and machines alike, but that only human live translation is based so crucially on multiple, complex meaning-making processes as to deserve to be called interpreting.

Conclusion

Mindful that defining interpreting as “Translation” (translational activity) exposes interpreting scholars, in a productive sense, to advances in conceptualizing the superordinate concept, I have explored two far-reaching deductive proposals – Marais’s (Citation2019) biosemiotic theory based on Peircean semiotics and Greco’s (Citation2018) universalist conception of (media) accessibility grounded in human rights. Neither theoretical framework has much regard for interpreting “as we know it”, which appears peripheral and tends to become displaced by “translation” and “access(ibility)”. In line with the options provided by Peircean usage as discussed in Marais (Citation2019), I have suggested repositioning interpreting in the broader theoretical framework and foregrounding “translation” to denote the basic-level concept of communication-enabling or access services, while ultimately reaffirming the place of “interpreting” in the terminology of translation studies.

In discussing recent forms of communication access services such as live subtitling and speech-to-text interpreting, I have drawn attention to the need for placing scholarly proposals in the broader social context and negotiating theoretical stances in interrelation with other stakeholder positions, such as various types of service providers and user groups. Introductory reflections on my positionality in this endeavour – as an interpreting scholar, educator, trained professional interpreter and member of a national standards committee – should help appreciate the set of interests that cannot easily be dissociated from this contribution to academic debate. Even so, it may be hard to say where scholarly argument ends and “boundary work” (Grbić Citation2010) in the interpreting profession(s) begins.

As also acknowledged at the outset, the epistemic position adopted in the present discussion is shaped to a considerable extent by the language of publication. Much of my case for reconceptualising interpreting rests on the English terms at the heart of Peircean semiotics; the approach from the notion of accessibility to define interpreting as a human live communication-access service would require different wording if it originated from the corresponding German term Barrierefreiheit; and the struggle to get intralingual STTI accepted as a form of interpreting might succeed more easily for its well-established German designation as Schriftdolmetschen (“written interpreting”). It will be worth monitoring whether or how the scholarly discourse on reconceptualisation will be taken up and develop in other linguistic and sociocultural contexts, its outcomes ideally made accessible to other members of the scientific community by means of translation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Franz Pöchhacker

Franz Pöchhacker is Professor of Interpreting Studies in the Center for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna. Trained as a conference interpreter, his interests have expanded to include issues of interpreting studies as a discipline, media interpreting and community interpreting in healthcare, social service and asylum settings. His more recent work involves video remote and speech-to-text interpreting. He has lectured and published widely, his English books including The Interpreting Studies Reader (2002), Introducing Interpreting Studies (2004/32022) and the Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies (2015). He is co-editor, with Minhua Liu, of Interpreting: International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting.

References

- Bogucki, Łukasz, and Mikołaj Deckert, eds. 2020. The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2.

- Braun, Sabine. 2015. “Remote Interpreting.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by Franz Pöchhacker, 346–348. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Carreres, Ángeles, and María Noriega-Sánchez. 2020. “Beyond Words: Concluding Remarks.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 198–203. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Deckert, Mikołaj. 2020. “Capturing AVT and MA: Rationale, Facets and Objectives.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility, edited by Łukasz Bogucki, and Mikołaj Deckert, 1–8. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2_1.

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge, Pilar Orero, and Aline Remael. 2007. “Media for All: A Global Challenge.” In Media for All: Subtitling for the Deaf, Audio Description, and Sign Language, edited by Jorge Díaz Cintas, Pilar Orero, and Aline Remael, 11–20. Amsterdam: Rodopi. doi:10.1163/9789401209564_003.

- European Union. 2019. Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the Accessibility Requirements for Products and Services. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/882/oj. Accessed 30 November 2022.

- Fantinuoli, Claudio. 2018. “Interpreting and Technology: The Upcoming Technological Turn.” In Interpreting and Technology, edited by Claudio Fantinuoli, 1–12. Berlin: Language Science Press.

- Gambier, Yves. 2003. “Introduction. Screen Transadaptation: Perception and Reception.” The Translator 9 (2): 171–189. doi:10.1080/13556509.2003.10799152.

- Grbić, Nadja. 2010. “‘Boundary Work’ as a Concept for Studying Professionalization Processes in the Interpreting Field.” Translation and Interpreting Studies 5 (1): 109–123. doi:10.1075/tis.5.1.07grb.

- Greco, Gian Maria. 2018. “The Nature of Accessibility Studies.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 1 (1): 205–232. doi:10.47476/jat.v1i1.51.

- Greco, Gian Maria, and Anna Jankowska. 2020. “Media Accessibility within and beyond Audiovisual Translation.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility, edited by Łukasz Bogucki, and Mikołaj Deckert, 57–81. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2_4.

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The Mediatization of Culture and Society. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203155363.

- Holmes, James S. 1972/2000. “The Name and Nature of Translation Studies.” In The Translation Studies Reader, edited by Lawrence Venuti, 172–185. London: Routledge.

- Iedema, Rick. 2003. “Multimodality, Resemiotization: Extending the Analysis of Discourse as Multi-Semiotic Practice.” Visual Communication 2 (1): 29–57. doi:10.1177/1470357203002001751.

- ILSA. 2020. “ILSA Project: Interlingual Live Subtitling for Access.” http://ka2-ilsa.webs.uvigo.es/project. Accessed 30 November 2022.

- ISO. 2019. ISO 20539:2019 Translation, Interpreting and Related Technology – Vocabulary. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- ISO. 2022. ISO 24019:2022 Simultaneous Interpreting Delivery Platforms – Requirements and Recommendations. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- Jakobson, Roman. 1959. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” In On Translation, edited by Reuben A. Brower, 232–239. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674731615.c18.

- Jankowska, Anna. 2020. “Audiovisual Media Accessibility.” In The Bloomsbury Companion to Language Industry Studies, edited by Erik Angelone, Maureen Ehrensberger-Dow, and Gary Massey, 231–259. London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781350024960.0015.

- Kade, Otto. 1968. Zufall und Gesetzmäßigkeit in der Übersetzung. Leipzig: Verlag Enzyklopädie.

- Kaindl, Klaus. 2020. “A Theoretical Framework for a Multimodal Conception of Translation.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 49–70. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429341557-3.

- Kress, Gunther. 2020. “Transposing Meaning: Translation in a Multimodal Semiotic Landscape.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 24–48. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429341557-2.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

- Lederer, Marianne. 2015. “Paris School.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by Franz Pöchhacker, 295–297. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Marais, K. 2019. A (Bio)Semiotic Theory of Translation: The Emergence of Social-Cultural Reality. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315142319.

- Marais, Kobus, ed. 2022. Translation beyond Translation Studies. London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781350192140.

- Marciniak, John J., ed. 2002. Encyclopedia of Software Engineering. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471028959.

- Martín de León, Celia. 2020. “Functionalism.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, 3rd ed., edited by Mona Baker, and Gabriela Saldanha, 199–203. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315678627-43.

- Merriam-Webster. 2022. “Live.” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/live. Accessed 30 November 2022.

- Olohan, Maeve. 2011. “Translation and Translation Technology: The Dance of Agency.” Translation Studies 4 (3): 342–357. doi:10.1080/14781700.2011.589656.

- Ong, Walter J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen. doi:10.4324/9780203328064.

- Orero, Pilar. 2004. “Audiovisual Translation: A New Dynamic Umbrella.” In Topics in Audiovisual Translation, edited by Pilar Orero, vii–xiii. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.56.01ore.

- Pérez-González, Luis, ed. 2019. Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315717166.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2011. “Researching Interpreting: Approaches to Inquiry.” In Advances in Interpreting Research: Inquiry in Action, edited by Brenda Nicodemus, and Laurie Swabey, 5–25. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.99.04poch.

- Pöchhacker, Franz, ed. 2015a. Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315678467.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2015b. “Simultaneous Consecutive.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by Franz Pöchhacker, 381–382. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2019. “Moving Boundaries in Interpreting.” In Moving Boundaries in Translation Studies, edited by Helle V. Dam, Matilde Nisbeth Brøgger, and Karen Korning Zethsen, 45–63. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315121871-4.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2021. “Multimodality in Interpreting.” In Handbook of Translation Studies. Volume 5, edited by Yves Gambier, and Luc van Doorslaer, 151–157. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/hts.5.mul3.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2022a. Introducing Interpreting Studies. 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003186472.

- Pöchhacker, Franz. 2022b. “Interpreters and Interpreting: Shifting the Balance?” The Translator 28 (2): 148–161. doi:10.1080/13556509.2022.2133393.

- Pöchhacker, Franz, and Aline Remael. 2019. “New Efforts? A Competence-oriented Task Analysis of Interlingual Live Subtitling.” Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series ‒ Themes in Translation Studies 18: 130–143. doi:10.52034/lanstts.v18i0.515.

- Powell, Robert B., and Marc J. Stern. 2021. “Journal of Interpretation Research: Research is Necessary to Underpin the Field in Evidence.” Journal of Interpretation Research 26 (2): 47–48. doi:10.1177/10925872211067833.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo. 2015. “Respeaking.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by Franz Pöchhacker, 350–351. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo. 2019. “Respeaking: Subtitling through Speech Recognition.” In Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation, edited by Luis Pérez-González, 96–113. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315717166-7.

- Salama-Carr, Myriam. 2009. “Interpretive Approach.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, 2nd ed., edited by Mona Baker, and Gabriela Saldanha, 145–147. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Toury, Gideon. 1986. “Translation: A Cultural-Semiotic Perspective.” In Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, edited by Thomas E. Sebeok, 1111–1124. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Toury, Gideon. 2012. Descriptive Translation Studies – and beyond. Revised Edition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.100.

- Translatio. 1995. Audiovisual Communication and Language Transfer. Special Issue of Translatio: Nouvelles de la FIT–FIT Newsletter 14 (3/4).

- Tsuruta, Chikako. 2015. “News Interpreting.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by Franz Pöchhacker, 276–277. Abingdon: Routledge.

- United Nations. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Resolution 61/106 Adopted by the General Assembly. New York: United Nations.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia. 2017. “Translation as a Metaphoric Traveller across Disciplines. Wanted: Translaboration!” Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 3 (3): 388–406. doi:10.1075/ttmc.3.3.07zwi.