ABSTRACT

In the era of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automation, studying human behaviour is becoming ever more pressing. The variety of human behaviour within translation studies (TS) research has been given some attention, but the area of individual differences in translators, especially regarding their translation-oriented research activities, has received little consideration in either TS or Information Behaviour (IB) studies. This article reports on a quasi-naturalistic, observational, mixed methods study of professional translators’ research activities designed to capture the similarities and differences in how those activities are carried out. The outcome is a taxonomy of translation-oriented research styles which illustrates the wide spectrum of research behaviours as observed and reported by sixteen participants, but the article also points towards a potential tendency for the homogenization of translation-oriented research behaviour in the digital age.

Introduction

With the recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), insights into human factors are needed more than ever if we want to “go digital, [but] stay human” (Kromme Citation2017). Those insights are important to inform future system designs and to determine what features of human performance are key for future tasks, including translation tasks. In particular, insights are needed into human–computer interactions and, by extension, into human-information interactions in digital environments. Translation, as an activity underpinning global trade, knowledge exchange, and international relations, relies on a constant interaction with information in the pursuit of its ultimate goal – connecting with audiences. Furthermore, because translators can work with any imaginable kind of text, the need for efficient and effective use of information becomes extremely important to achieve this connection. Therefore, we need to continuously improve our understanding of how translators interact with information, how they use resources that contain this information, and, more broadly, how they carry out research for translation.

In the current “man vs machine” dichotomy underpinning much of public discourse, it is easier than ever to forget about the inherent variability of human behaviour. Although we can say that there are “general laws and universal mechanisms underlying human behaviour” (Szalma Citation2009, 383), people differ in the way they behave, learn, translate, or look for information. Hence the existence of two broad approaches to studying human behaviour – the universal and the individual, known in psychology as nomothetic and idiographic approaches, respectively (DeFreese and Nissley Citation2020). Although both approaches are represented in translation studies, more attention has so far been paid to the universal and shared aspects, thus creating a need to balance it with research on what is individual and personal. According to Hansen, we need to study diversity and individuality in order to gain “better knowledge about the structure of individual translation processes and personal translation styles” (Citation2013, 88). Research activities, whether acquiring background information about the topic, checking the exact meaning of the source word or phrase in context or looking for an equivalent in the target language, constitute an important part of the translation process. The present study responds to Hansen’s call and investigates the individual traits exhibited by sixteen translators working with different language pairs and directions when engaged in research activities. In turn, and building on notions of style employed in information studies and translation studies, the article attempts to systematise the individual differences, offering a first of its kind taxonomy of translation research styles; not only to draw attention to the variety of human behaviour in this area, but also to highlight the potential tendency for homogenization of this behaviour in the digital age.

Previous literature on styles and individual differences

Inspired by sciences of mind and behaviour, there has been an abundance of empirical research and conceptual theorization about styles. According to Zhang, Sternberg, and Rayner (Citation2012, 1), in psychology, the notion of style was first introduced in 1937 by Allport who referred to “styles of life” which can be understood as a “means of identifying distinctive personality types or types of behaviors”. Since then, various style constructs referring to “one’s preferred way of processing information and dealing with tasks” have emerged (Zhang and Sternberg Citation2005, 2). In Information Science, those which draw on psychology and on the observation of various information-focussed occupations can be subsumed under the more general term “information styles” (Spink and Heinström Citation2011, 128). In information behaviour (IB), more specifically, a style can be seen as “an instinctive human mechanism, developed and expressed in interaction with the environment” (Spink and Heinström Citation2011, 5). For the present research, the important aspects of this mechanism are that it can respond to various needs (e.g. solving translation problems) and that it can be influenced by individual differences. This “instinctive human mechanism” can thus be used as a lens to study how translators carry out research for translation.

Literature from IB, especially studies concerned with information behaviour patterns, or information styles, of other professions can help understand translator information behaviour and potentially reveal shared characteristics between translators and other user groups. Case and Given (Citation2016, 278) report that approximately half of all IB studies have an occupational sample, including scientists, engineers, scholars, health care workers, managers, journalists, lawyers, farmers, artists, and other professions. However, no studies on language workers have been included in the latest edition of the Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs and Behaviour (Case and Given Citation2016). This is surprising, since the area of human information behaviour is concerned with “how people need, seek, manage, give and use information in different contexts” (Fisher, Erdelez, and McKechnie Citation2006, xix), and translators represent a group of professional workers whose work heavily relies on information and who are considered information users, processors, and producers (Pinto and Sales Citation2008, 413).

One of the professions most studied in IB literature is scientists (Case and Given Citation2016). Palmer (Citation1991), for example, studied sixty-seven scientists’ information styles and, based on two different methodologies, identified two typologies. Through a statistical cluster analysis, Palmer identified “non-seekers” (who did little information gathering), “lone, wide rangers” (who consulted a wide range of resources and worked alone), “unsettled, self-conscious seekers” (conscientious seekers, but anxious about underusing resources), “confident collectors” (who felt in control of their research strategies), and “hunters” (with narrowly defined goals, but industrious, organized, predictable and in control). However, a different taxonomy emerged through the analysis of interviews with the scientists on their information habits. The following styles emerged: “information overlord” (who operates an extensive and controlled information environment); “information entrepreneur” (who creates an information-rich environment using many sources and strategies); “information hunter” (organized and predictable information gatherer with a narrow focus); “information pragmatist” (occasional gatherer of information, only when the need arises); “information plodder” (who rarely seeks information, relying on their own knowledge or personal contacts); and “information derelict” (non-user of information with no apparent information need or system for searching or organizing). Such typologies, as Palmer observes, are context-dependent, but they could also represent the innate characteristics of information seekers and could therefore potentially apply to other professions.

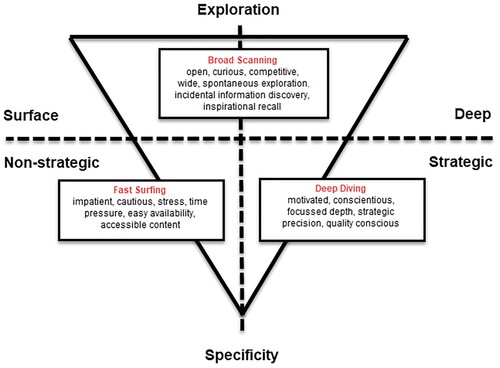

Another research project investigated the information seeking patterns of MA students in relation to their discipline of study, approach to studying, and personality (Heinström Citation2006). Based on two predominant cognition and problem-solving styles the convergent-rational and divergent-intuitive (Edwards Citation2003) and the analytical framework based on the “broadness versus specificity” (Heinström Citation2006, 1440), three information seeking styles were identified: “broad scanning”, “fast surfing”, and “deep diving” (see ).

Figure 1. Information seeking styles of MA students. Adapted from Heinström (Citation2006, 1449).

Similarly, broad patterns were reported by White and Drucker (Citation2007) who identified two general types of users: “navigators”, whose web search patterns are highly consistent, and “explorers”, whose interactions are highly variable.

Furthermore, Kohnen and Mertens (Citation2019) report on a study of expert information seekers such as journalists, librarians, and writers. The study found that, despite having “unique communities of practice and activity systems for their work, [the information seekers] appeared to share a generalist or expert information-seeking identity”, and described their traits as innate (Kohnen and Mertens Citation2019, 292).

The IB literature may therefore suggest that, on the one hand, information behaviour can be context-, environment- or discipline-specific, but, on the other, there seem to be some shared characteristics amongst the different user groups. Therefore, it can by hypothesized that translators might have their own unique behaviours associated with their community of practice, but they might also share some behaviours with information seekers more generally, pointing towards a set of innate characteristics.

Within the discipline of translation studies, studies concerned with the use of resources or, more broadly, with the information behaviour of translators can be categorized into two types: “user-centred” and “system-centred” (Case and Given Citation2016). Of interest to this study are the “user centred” studies, i.e. those addressing process-related translator behaviours or working styles that focus on individual users and their needs, rather than on information sources and how they are used. Such “user-centred” studies have focussed on web search behaviour (Cui and Zheng Citation2021; Enríquez Raído Citation2011; Shih Citation2019), information literacy and pedagogical aspects of its implementation (Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow Citation2011; Sales and Pinto Citation2011), the development of competences to carry out translation-oriented research (Hurtado Albir Citation2017; Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018; Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow Citation2011; Pinto and Sales Citation2008; Pinto et al. Citation2010, Citation2014), and cognitive effort when using resources (Hvelplund Citation2019). However, within the “user-centred” studies in translation-oriented research, there has been little focus on a systematic examination of individual differences.

The earliest mention of individual differences in translator research behaviour can be seen in data obtained by Nord in 1997, in a study of the use of resources by professional translators in the pre-internet era (Nord Citation2009). Several more recent articles also make references to this aspect; for example, Kuznik and Olalla-Soler (Citation2018, 46) admit that individual differences in student translators “almost certainly exist”, but were not examined in their study. Indeed, the existence of such individual differences could be supported by their findings in which no difference was found between research patterns and quality of produced translations, which could mean that translators arrive at acceptable solutions in a variety of ways, regardless of how many searches were performed or what resources were used.

Considerable variety in translator behaviour during research activities was also reported by Hvelplund (Citation2017, 83), indicating that “the number of different types of digital resources used by a translator may be an indicator of their search profile”. Enríquez Raído’s (Citation2011) study also suggests the existence of certain patterns associated with the intensity of translators’ search activities. Enríquez Raído’s “shallow” style was associated with horizontal “checking and comparing type of search behaviour … [involving] easy, fast, and more or less cursory visits to a few selected websites” (Enríquez Raído Citation2014, 139–140) and can be compared to Heinström’s “fast surfer”. The “interactionistic” style involving a type of search based more on browsing, i.e. following internal links, performing site queries, and spending more time reading to acquire background information (139–140), can be likened to Heinström’s “deep diver”. The styles identified by Enríquez Raído’s were, however, not linked to the “inherent human mechanism”, but to factors such as the level of expertise and declarative knowledge of translation of the individual participants.

When considering taxonomizing individual differences, insights from these studies are limited since their main focus was not to uncover any potential similarities, groupings, or styles amongst translators. The only comprehensive study on research styles by Sycz-Opoń (Citation2021) revealed six styles based on a direct observation of 104 translation students in a lab setting, where think-aloud protocols were used. The styles included: “traditionalists” (mostly experienced users of dictionaries and printed sources), “digital natives” (who only use online resources, often indiscriminately), “minimalists” (who only consult resources when needed and often rely on internal resources), “true detectives” (who carry out frequent, in-depth consultations), and “habitual doubters” (who are frequent information seekers due to lack of trust in their internal and external resources). In terms of overlaps with IB studies, Sycz-Opoń’s (Citation2021) “minimalists” can be compared to Palmer’s (Citation1991) “non-seekers” or “information plodders”. Sycz-Opoń’s study offers a classification based on qualitative observations in a lab setting and, despite an impressive sample, focussed on students, not professional translators. To the best of my knowledge, no mixed-methods study focussing on individual differences of professional translators’ research activities in a naturalistic setting has so far been conducted.

This study responds to Heinström’s call for more research “related to work tasks” (Citation2006, 1449) of other professions and addresses a research gap in translation studies and information behaviour studies by investigating research activities of professional translators through direct observation in a non-laboratory setting. The value of this study lies in its novel, mixed methods approach designed to capture the richness and the complexity of the translation-oriented research activities from the quantitative and qualitative perspective. Furthermore, by studying commonalities and differences between participants, this study attempts to taxonomize this diversity, which is seen in science as a “fundamental task [that] provides reference models for many fields of research and applied settings” (Uher Citation2018). The methodology developed for this study made it possible to arrive at a spectrum of behaviours onto which the individual translators were mapped, culminating in a taxonomy of translation research styles. It is proposed that profession-focussed styles can reflect both the innate and the acquired characteristics of human behaviour, including the way we interact with technology. Hence, the proposed taxonomy is an attempt at representing the innate and acquired aspects of translator behaviour during their translation-related research activities, thus contributing to a more holistic understanding of how translators approach and carry out translation-oriented research activities and what are the similarities and differences of their research behaviour.

Methodology

The typology of translator research styles presented in this paper is based on a quasi-naturalistic, observational study of sixteen professional freelance translators who were tasked with translating a 412-word financial text on Bitcoin and the concept of digital currency (Summerfield Citation2013) from English into their mother tongue. The observation via screen recordings and think-aloud protocols was complemented with profile questionnaires and post-tasks interviews. The translators had varying levels of experience (three to thirty years) and their mother tongues were Spanish (n = 6), Polish (n = 3), Portuguese (n = 2), Brazilian Portuguese (n = 1), French (n = 1), Dutch (n = 1), Hungarian (n = 1), and Indonesian (n = 1). The participants carried out the task in their usual place of work, using their usual tools and resources. It was noted that four translators used translation memory tools and four used machine translation, and only one used a paper resource such as a dictionary. The translators screen-recorded their tasks and made the audiovisual data available for the analysis. Out of the sixteen participants, six reported having a prior understanding of the topic. Since at the time of the data collection the concept of Bitcoin was still relatively novel, the assumption was that it would present numerous opportunities for the translators to conduct translation-oriented research activities (TRA). This includes terms like “crypto-currency”, “fiat money”, “gold standard”, “hard currency”, and “peer-to-peer”, as well as words with multiple meanings like “haircut” and “mining”. The world “disruptive” was also considered noteworthy due to its new connotation related to technology and innovation. Additionally, the text featured named entities such as “WIR Bank”, “Liberty Reserve”, and “Ithaca Hours” which, despite sounding like financial institutions, are alternative currency systems. Phrases like “wild swings” and “the rise of” were also identified as rich points since they require some adaptation when translated in the context of digital currency.

Several tools were used to collect and analyze the data. MAXQDA, a software programme for qualitative and mixed method analysis, was used to code and analyze the data collected from questionnaires, screen recordings, and TAPs. The screen recordings were captured using the Screencast-O-Matic platform.

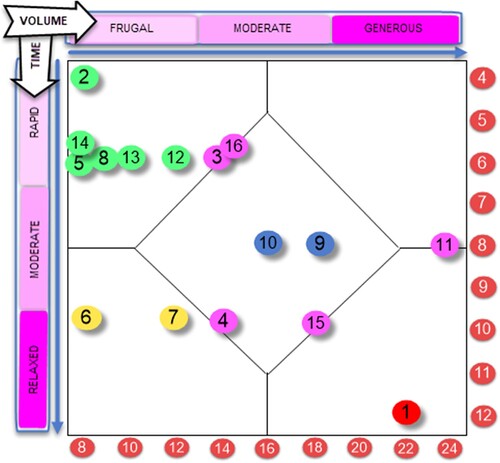

Two groups of categories of translator research behaviour, primary and secondary, were created as part of the analytical framework. The primary categories were based on a quantitative analysis and were derived from the many aspects of research behaviour observed in the screen recordings. The primary categories were further divided into two groups, volume-related and time-related, as illustrated in .Footnote1

Table 1. Primary categories and their sub-categories.

Primary categories, apart from Research Unit Volume, comprised sub-categories, and each sub-category was further divided into high, medium, and low values which were based on the range of numerical values that were observed for each sub-category. For example, as seen in , the Research Time category was composed of: (1) research time in hours, minutes, and seconds; and (2) research time as a percentage in relation to the whole translation task. The numerical range observed for each sub-category was divided into three values – high, medium, and low, according to the observed ranges.

Table 2. Example of the subdivision of a Primary Category into sub-categories and their categorisation into high, medium, and low values depending on the numerical values observed in the screen recordings.

The values of the sub-categories were aggregated and given descriptive labels: “generous”, “moderate”, and “frugal” for the volume-related categories, and “relaxed”, “moderate”, and “rapid” for the time-related categories. See for an example.

Table 3. Example of how descriptive labels were assigned based on the low, medium and high values.

Then, the descriptive labels were assigned weight scores as follows:

Frugal and Rapid – a score of 2

Moderate – a score of 4

Generous and Relaxed – a score of 6

This was done in order to create numerical ranges for time- and volume-related axes (see for an example) which allowed translators to be placed on a two-dimensional TTRS (Typology of Translation Research Styles) grid with volume-related features on the x-axis and the time-related features on the y-axis, as shown in .Footnote2

Figure 2. TTRS grid showing the positioning of individual translators according to their weight scores for primary categories.

Table 4. Example of how weight scores were assigned to descriptive labels in order to create numerical ranges for time- and volume-related axes on the TTRS grid.

Secondary, qualitative categories were obtained from screen recordings, profile questionnaires, and post-task e-mail questionnaires, and were coded on an ad hoc basis, assigning them to participants who displayed behaviours related to those categories. displays the fourteen secondary categories that were identified from the data.

Table 5. Secondary categories and their description.

The secondary categories were assigned to translator’s profiles in a graded way, based on the degree of presence of a particular secondary category in each translator’s research activities. The weight scores, as shown in , established ranges that were categorized into three levels of presence: weakly present (WP), moderately present (MP), and strongly present (SP). A weight of 1 was assigned for weak presence, 2 for moderate presence, and 3 for strong presence.

Table 6. Weight system for assigning secondary categories to translators' profiles.

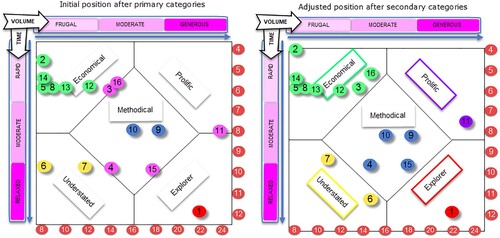

Each individual translator was evaluated for the presence of secondary categories, which either reinforced their current position on the TTRS grid or caused borderline translators to move to a neighbouring area of the grid, as illustrated in .Footnote3 Subsequently, style labels such as “prolific”, “explorer”, “methodical”, “economical”, and “understated” were assigned to each section of the grid, in order to capture the most prominent characteristics of each style.

Figure 3. TTRS grids showing repositioning of translators due to the influence of secondary categories.

The study has several limitations primarily associated with its ecological validity, which was not completely achieved due to various factors. First, the text was predetermined and arguably too short to be considered a realistic assignment. Secondly, the sample of participants was relatively low and unevenly distributed across different language pairs and directions. Moreover, the extensive data collection of the translation process in terms of volume and time-related categories inevitably led to other aspects of analysis not being given due attention. These include the translators’ external environment such as availability and quality of sources in different language pairs, specific working conditions, and their internal environment such as memories, predispositions, motivations, etc. (Case and Given Citation2016, 48). This is a significant limitation given Spink and Heinström’s (Citation2011) definition of style as being developed and expressed in interaction with the environment. Nevertheless, the results of this study can provide a hypothesis that can be further tested by including more participants and additional variables related to the external environment of the participants.

Findings

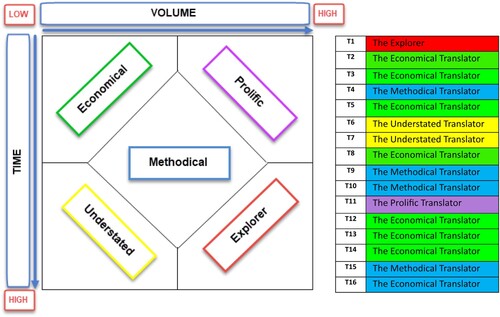

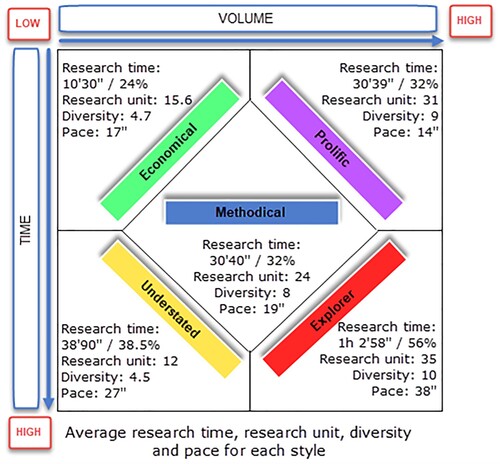

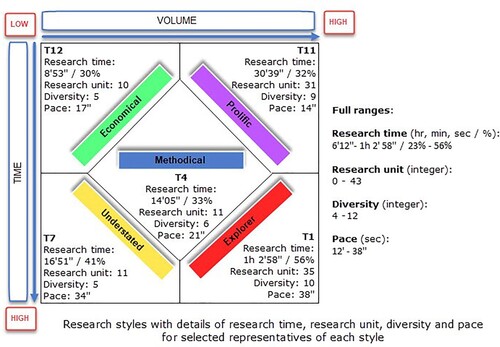

Based on the observed and reported research behaviour of the sixteen translators who took part in this study, the following five research styles emerged: the “prolific translator”, the “explorer”, the “methodical translator”, the “economical translator”, and the “understated translator”. shows the final classification of the sixteen translators according to their research style.

Although taxonomies based on small samples can be seen as simplistic representations of complex phenomena (Bailey Citation1994, 15), they can also be very effective in bringing order out of chaos given their capacity to “transform the complexity of apparently eclectic congeries of diverse cases into well-ordered sets of a few rather homogeneous types, clearly situated in a property space of a few important dimensions” (33). In the present study, this eclectic mix of professional translators was organized into groups based on the similarity or dissimilarity of the various aspects of their online research behaviour, but they do not necessarily exhibit all behaviours assigned to the category they belong to. It is also important to acknowledge that the taxonomy does not represent all possible aspects of such behaviour; it only represents the spectrum of behaviours of this particular sample as a starting point for further research. Below, each research style is described in terms of the shared aspects of the research behaviour of its members (or distinct aspects of this behaviour where there is only one member), followed by a description of the most prototypical members of the categories who are described as “cases”.

The explorer

Explorers enjoy researching and prioritize perfection over efficiency. They research not just to satisfy their research needs but also to go on a journey of discovery. The main feature of this style is the considerable effort that is put into the research activities. Explorers research many words, terms, and expressions using a broad variety of resources to look for ideas and inspirations, and they are keen to understand the nuances rather than settle for shallow comprehension. Their translation-oriented research is characterized by deep searches and a relaxed pace. Many of their research episodes are short as explorers like to check and double check their solutions as well as refine their choices. However, due to their inquisitive nature, explorers can also have some very long research episodes, in terms of both the number of steps and the time taken to find a solution. Therefore, their overall research intensity can be classified as medium. Search paths are often meandering and branch out, and sometimes explorers prolong their research just to satisfy their curiosity or deepen their subject knowledge. They like to record their findings in termbases or glossaries and are likely to engage in communities. They can be very organized in their approach to research, but their research behaviour can sometimes appear chaotic due to the lack of routines. This could be due to their more creative style which favours an individual approach to each translation problem rather than following pre-established research paths. The explorer could be loosely compared to Sycz-Opoń’s “true detective style” (Citation2021, 144–145) or Palmer’s “information entrepreneur” (Citation1991, 123). A combination of broad scanning and deep diving characteristics proposed by Heinström (Citation2006) could also be attributed to the explorer.

The explorer in this sample is T1, a sworn-certified English to Spanish translator and interpreter aged 50–59, with over thirty years of experience in healthcare/medical, security/military, legal, finance/business, and literary translation. In the post-task questionnaire T1 reported a high level of experience in financial translation and being comfortable with the text despite not having much previous experience with digital currency.

T1 researched a total of thirty-five research units using nineteen resources. Due to the high number of RUs and high resource volume, their overall research volume fell into the generous range. T1’s resource diversity was very high as they accessed many specific resources (19), as well as a wide variety of resource types (10) and used them frequently (100 instances of resource use in the task). The total research time for T1 was 1 h 0’ 58” which was by far the longest recorded time for the task. Admittedly, the reported internet connection was slow, which had an impact on the length of the process. However, given that in the post-task questionnaire T1 reported not completing the usual QA steps (which could require more time for research), it could be said that T1’s research time was generous.

Due to the extensive use of resources, T1’s research patterns were characterized by many breaks in the flow of the translation, with frequent flicking between the texts and resources, although the actual duration of many research episodes was relatively long. The intensity of T1’s research appears to be moderate due to the balance between the number of long, medium, and short, one-step consultations. Considering all this complex research activity, T1 was very organized, with all resources neatly arranged in a specially created tab listing all frequently used sources. A colour-coding system was also used to help T1 remember which parts of the translated text they needed to revisit. T1 kept a record of the solutions and often saved them in a personal glossary. T1 also contributed to community-based resources such as ProZ Glossaries and was observed to cast a vote on community-based sites. T1 followed many meandering research paths and moved in a sequential manner (i.e. opening one tab at a time) but no repetitive behaviour was observed within the sequences. Instead, T1 tended to rely on the strategies they had developed to find the type of knowledge required. T1 knows their resources well, understands what to expect from them, and uses them to “find a better or a more specific term” in the often-lengthy pursuit of the perfect solution, which frequently includes an emotional assessment of the solution as well.

The prolific translator

The prolific translator is in many ways similar to the explorer. The prolific translator enjoys the discovery process and adopts a creative rather than routinized way of finding information. The wide range of specific resources and types of resources used, as well as the high frequency of resource use, are also evidence of their high research volume. However, prolific translators process their high RU volume much faster than explorers, which is expressed in their high research intensity. Their approach is characterized by research episodes that are moderate in length and comprise a moderate number of research steps, but these episodes are shorter than those of the explorer, resulting in a moderate to rapid research pace. A prototypical prolific translator would, therefore, process a great number of RUs using a high number of varied resources in a relatively short time. Similar to the explorer, they have a tendency to go deeper in their search; however, that depth is not related to the time expended but rather to the volume of material consulted. Prolific translators might exhibit some meandering research paths and squirrelling behaviour, but when consulting vast amounts of resources in a short period of time, they will mostly use techniques such as parallel search or snippet viewing to maximize the recall and, consequently, their exposure to potential solutions. They might also use machine translation for the same purpose. This style could be loosely compared to Palmer’s “information overlord” style (Citation1991, 123). A combination of broad scanning and fast surfing characteristics explored by Heinström (Citation2006) could also be attributed to the prolific translator.

The dataset did not, however, reveal a clear prolific translator. The closest to this style was T11 who is an English into Polish translator aged 30–39 with five years of experience. T11 specializes in law, business, and administration and has an MA in Translation. This translator reported having no previous experience with digital currency but had translated business material and felt relatively comfortable about the text.

T11 researched thirty-one research units and used nine types of resources and twenty-eight specific resources which were accessed on 138 occasions. The total recording time was second longest (1h 58’ 23”), with translation taking 1h 04’ 57” and research 30’ 39”. T11’s research was characterized by a prolific use of parallel texts and frequent consultations in Google Translate (GT). T11’s use of dictionaries and other termino-lexicographic resources was limited; instead, information was gathered from the many parallel texts T11 had read in advance and during the translation task. Another search strategy frequently utilized by T11 was to consult GT, often out of curiosity or to find collocations, by putting words, phrases and even sentences to see “how it [GT] would translate it”, followed by a search in Google and Wikipedia or in an already open parallel text. T11 displays characteristics of an explorer, such as meandering, squirrelling (by adding words to the Word dictionary during the spellchecker), and affective assessment (especially regarding GT output), but they also performed a lot of parallel searches, with a score of twenty-one instances, the highest in the sample. T11’s modus operandi when searching through Google results was to click on the links of possible interest and open them in separate windows, sometimes three or four from a single page of Google results. T11’s browser was always full of opened tabs, and a separate “tab closing” action had to be performed during the task. The results pertaining to the primary categories positioned T11 on the border of the explorer and the prolific. However, the distinctive feature of high research intensity combined with relatively fast processing of such a high number of consultations per research unit moved T11 up the “time” axis to be classified a prolific translator.

The methodical translator

The methodical translator carries out research in a systematic mode rather than in a discovery mode. The main characteristic of this type is moderation, which is often self-imposed by means of self-organization and planning in the initial phase or by having clear strategies for dealing with various types of translation problems. Advanced search is also often used as part of the planned strategies. The methodical type has moderate research volume and research time, although sometimes this may fall towards the lower end of the scale. The diversity of the resources is also mid-range and the searches moderate in depth. Overall, the methodical translator tends to display research behaviour that centres on the middle ranges. Search paths are mostly straight, resources are accessed in a sequential manner, and open browser tabs are kept to a minimum. All four methodical translators self-declared that they were innovators/early adopters. This style could be loosely compared to Palmer’s information “hunter style” (Citation1991, 123).

The most prototypical translator in this category is T4, an English to Spanish translator aged below 29 who holds two MAs in Translation – Audiovisual and Medical – and now specializes in those domains. Having researched eleven units, T4’s research volume was at the lower end of the spectrum. Despite having no experience with the subject of digital currency, T4 was “still comfortable with the text” as it “did not present too many problems”. T4 is a typical planner who read the text systematically, highlighted the RUs that would be researched, and then methodically proceeded with the translation, not researching anything else but the highlighted RUs. While translating, T4 displayed strategic behaviour in repetitively formulating queries in the same way and using advanced Google searches. T4 proceeded in a straight path and in a sequential manner; they did not diverge from anything that was not planned at the beginning of the task.

The economical translator

Economical translators are characterized by a pragmatic attitude towards research. The key factors driving their research are time and efficiency, and their research effort is inversely proportional to that of the explorer. They are fast-paced and only research essential items in the source text; therefore, there is little checking or confirming behaviour in their searches that are mostly shallow, composed of few steps, and they follow straight paths. This style is characterized by routine behaviour where searches are frequently initiated using the same resource or the same combination of resources, sometimes independently of the type of knowledge sought. Economical translators have high retentive memory,Footnote4 which might contribute to their low research needs. They tend to use machine translation to aid their research process or speed up the translation process. They are often end-revisers and five out of eight economical translators performed rapid draft translation with long end-revision. To summarize, the economical translator is a fast researcher for whom research is not an activity they delve into deeply. This style could be loosely compared to Sycz-Opoń’s “minimalist” style (Citation2021, 142–143) and Palmer’s “information pragmatist” style (Citation1991, 123).

An example of economical style is T16, who is an English to Spanish translator, aged 30–39, with six to ten years of experience, specializing in business and marketing, IT, and healthcare alongside doing a lot of general translations. T16 has an MA in Translation and Interpreting and reported being familiar with the subject matter and comfortable with the text, due to having previously read about the topic.

In the translation task, T16 was observed to investigate eight research units using seven types of resources and eleven specific resources. T16’s timings were the shortest of all participating translators,Footnote5 with the total recording time of 28’ 33” (translation time 16’ 44” and research time 6’ 12”). The searches were fast, shallow, and cursory, carried out to obtain only the most necessary information.

In the post-task questionnaire, T16 declared to be neither research-intense nor methodical, but generally tried to acquire as much information as possible beforehand. At the same time, T16 recognizes that “ultimately, there will be [unforeseen] problems during the translation process […], so there is no point spending a lot of time trying to foresee those”. Lastly, during the TAP, T16 talked about efficiency and how, due to time pressures in the industry, they felt the need to adapt to a different way of dealing with source texts, i.e. faster, and more efficient. Being initially positioned on the border with the methodical style, T16’s position was adjusted to fit the economical style due to the strong influence of secondary categories.

The understated translator

The main characteristic of the understated translator can be summed up by the “less is more” maxim. Frugality is the main feature of this type of translator; they will only research items that are absolutely necessary to achieve the goal of their translation. Therefore, they research few words or terms and have at their disposal only a handful of resources which they access routinely to satisfy their research needs. Although they use few resources, the ones they do use are of different types, providing a variety to choose from depending on the research need. Understated translators’ searches might be sporadic, but they are marked by a high proportion of deep searches and indirect, serendipitous research. Understated translators are driven by perfection, but rather than progressing in an exploratory manner, they will use advanced search queries or well-established strategies to make sure their research needs are fully satisfied. To sum up, understated translators research little using a handful of reliable resources, but their research is thorough and exhaustive. This style displays the characteristics of “deep divers” explored by Heinström (Citation2006).

A good example of an understated translator is T7, who is a 50–59-year-old English to Brazilian Portuguese translator with eleven to twenty years of experience, specializing in IT, ERP software, and life sciences. They have a degree in engineering, but also attended unspecified translation courses. T7 was comfortable with the text and confirmed that the task resembled a real-life assignment, apart from not running a quality assurance (QA) tool.

T7 researched eleven research units using five specific resources, each of a different type, accessing them on thirty-one occasions during the task. T7’s total recording time was 46’ 03” (translation time 24’ 38” and research time 16’ 51”). The main characteristics of T7’s research were a moderate to relaxed pace and clear-cut strategies for dealing with word and world knowledge, e.g. the consistent use of a three-step strategy (find a definition in a monolingual resource, find an equivalent in a bilingual resource, confirm the equivalent in parallel texts in the target language).

Summary

As illustrated in , half of the sample clusters around the economical style. The second most populated category is the methodical style, accounting for 25% of the sample. The other styles have fewer representatives, and it is important to note that the prolific style did not have a clear representative after the initial positioning. Two translators (T3 and T6) were problematic regarding the final positioning. T3 displayed characteristics of the economical as well as the methodical style but scored slightly higher on the economical one and was therefore moved accordingly. T6, although initially positioned as understated, displayed strong secondary characteristics of the explorer and was therefore positioned very close to the explorer border to reflect this.

provides a summary of the most prominent characteristics of each research style which includes the primary characteristics, secondary attributes, and some additional descriptors for each style.

Table 7. Summary of characteristics of research styles.

Discussion

A systematic analysis of various aspects of the research behaviour of the translators taking part in this study revealed not only a wide range of different behaviours, but also a broad spectrum of these differences. For example, the average research time of the economical translator was 10’ 30” compared to 1 h 2’ recorded for the explorer. Similarly, the average number of Research Units of the economical translator was 15.6 compared to the 35 Research Units researched by the explorer. When the full spectrum of the differences is represented in a grid, the idea of “styles’ becomes conceivable, as illustrated in and .

Figure 5. Comparison of research styles according to average data based on selected primary categories.

Figure 6. Comparison of research styles according to data from selected representatives of each style based on primary categories.

The consideration of research styles as a factor impacting the translation process can contribute to a better understanding of that process. It is suggested that the variations in translators’ research behaviour may not be entirely dependent on variables such as expertise or domain knowledge but may also be influenced by personal preferences and natural predispositions. Furthermore, as seen in , the style does not seem to depend on the language, experience, or age of the participants, perhaps with the exception of methodical translators who belong to the younger age group (20–40) with 6–10 years of experience. These hypotheses should be further tested on larger samples or, ideally, repeated with the same sample on different text types and under different conditions.

Table 8. Comparison of styles against the age, language, and length of experience of translators.

An interesting observation can be made regarding the clustering around the economic style. Half of the sample congregates in one section of the matrix and displays economical research behaviour linked to low research volumes and low research times. This is important for the understanding of the impact of the realities of the translation market on the translation process and can possibly point towards the homogenizing effects of technology and market forces. This also mirrors what Kohnen and Mertens (Citation2019, 285) have highlighted as the interdependence between time limitations and level of depth of research in relation to expert information seekers more generally. Since no previous studies of the present type exist, it is difficult to ascertain whether this represents a compromise between a translator’s natural working style and market demands. The only evidence to support this is T16’s reported admission of feeling the need to adapt to the way the industry works by dealing with the source text in a more efficient way, for example by skipping the orientation phase. Interestingly, T16 was originally placed on the border with the methodical style which is associated with a more careful planning of research activities and was also close to the border with the prolific translator style due to the volume-related aspects of their research activities. This could mean that market demands might interfere with translators’ natural predispositions and working styles and could be linked to research into the so-called Google generation where shallow, horizontal, “flicking” search behaviour has been attributed to all web users: “all of us have changed the way they seek information. We are all the Google generation, the young and the old, the professor and the student and the teacher and the child” (Rowlands et al. Citation2008, 308). Perhaps the clustering of the professional translators in the economical section of the matrix supports their observations.

The second most densely populated section in the grid is the methodical translator who needs a degree of structure and planning in their research. The need for planning as a risk management strategy has been proposed by Gouadec (Citation2007, 70–73) who supports the extensive planning approach to translation by means of consulting translation briefs, carrying out pre-translation analysis, acquiring the knowledge and information required, setting up templates, terminology, etc. This is designed to reduce translation and research effort. Pym (Citation2010, np) disagrees with this excessively systematic approach arguing that the procedures are unnecessarily long and costly in relation to the potential risk, i.e. “the possibility of not fulfilling the translation’s purpose”, and that there “must still be room for experience, pragmatism, justified non-translation, creativity and inspiration”. The results of the present research would suggest that both Gouadec and Pym have a point in that how translators manage their translation process might depend on both their translation style and their research style. Therefore, any discussion around risk reducing strategies and management of the translation process also needs to take into account the fact that translators are not a homogeneous group, but rather individuals with their own preferences and styles.

Thus, it could be argued that methodical translators will thrive in an environment where some planning is required, for example, in technical or medical areas where terminology work is more strategic. In contrast, explorers might struggle to plan as they work in a discovery rather than a planning mode and would therefore be suited to a less time-constrained types of work, for example literary translation or transcreation. Similarly, while explorers are likely to make poor MT post-editors, economical translators will be more suited to this kind of work, being efficiency-driven and having no desire to wander off the chosen path.

Having said that, it is also possible that most translators can adapt to the external environment, i.e. to the demands of a particular task, moving along the volume- and time-related spectrum according to the individual circumstances of the assignment or the availability of resources in the given language pair. Such skills need to be considered in translator training. Nevertheless, the idea that professional translators can attune their performance to market demands should not obfuscate the fact that, in more ideal conditions, translators are likely to display their natural styles in accordance with their inherent predispositions because information behaviour, as Spink and Heinström (Citation2011) suggest, is an innate feature of human behaviour. It follows that all types of research behaviours need to be valued and encouraged to thrive, unless we resign ourselves to becoming more machine-like in our working patterns and fully yielding to certain pressures and demands of the market.

Finally, in the age of translation automation, what will distinguish texts created by humans from those created by AI are their higher levels of accuracy, nuance, creativity, and empathy. To achieve this, translators need to be able to look for information to satisfy more complex research needs, which in turn might involve research activities beyond quick, shallow, or cursory consultations for the most essential research units. Furthermore, if we agree that in the future we will still need human translators to deal with highly sensitive, impactful, or return on investment-dependent texts, we need to allow these translators to have some form of job satisfaction, part of which lies in knowledge acquisition, especially in the form of developing of existing or new specialisms. Translators look for information not only to satisfy immediate requirements of the text, but also to satisfy their curiosity, to learn something new, or to counteract other repetitive and tedious tasks. This was evident in the type of research T6 engaged in (see Gough Citation2019, 351). Restricting or discouraging individual, explorative, or prolific research tendencies through new technologies, workflows, or market demands, might have consequences not only for the quality of produced texts, but also on the availability of future human translators to carry out the most demanding translation tasks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joanna Gough

Joanna Gough is a lecturer in translation studies at the University of Surrey. Her research interests encompass a variety of language and technology related subjects, such as tools and resources for translators, process-oriented translation research, technology supported collaborative translation, and many more. She is also interested in the business and industry aspects of the translation profession and is a keen advocate of cooperation between academia and industry. She is involved in the ITI Professional Development Committee and is a LocLunch Ambassador.

Notes

1 See Gough (Citation2016, 63–65) for detailed definitions of concepts in and Gough (Citation2016, 196–213) for detailed descriptions and analysis of the primary categories.

2 See Gough (Citation2017, 20–28) for further details of the categories and the scoring model.

3 For detailed descriptions of the primary and secondary categories see Gough (Citation2017, 20–28).

4 Four out of eight identified economical translators said in the post-task questionnaire that their retentive memory is high (5 on a 1–5 scale, 5 being the highest).

5 Apart from T2, who did not carry out any research.

References

- Bailey, Kenneth D. 1994. Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Techniques. London: Sage Publications.

- Case, Donald O., and Lisa M. Given. 2016. Looking for Information. 4th ed. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Cui, Yixiao, and Binghan Zheng. 2021. “Consultation Behaviour with Online Resources in English-Chinese Translation: An Eye-Tracking, Screen-Recording and Retrospective Study.” Perspectives 29 (5): 740–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1760899.

- DeFreese, Elvis W., and Gerald E. Nissley. 2020. “Idiographic vs. Nomothetic Research.” In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Measurement and Assessment, edited by Bernardo J. Carducci, Christopher S. Nave, Jeffrey S. Mio, and Ronald E. Riggio, 19–23. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Edwards, John A. 2003. “The Interactive Effects of Processing Preference and Motivation on Information Processing: Causal Uncertainty and the MBTI in a Persuasion Context.” Journal of Research in Personality 37:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00537-8.

- Enríquez Raído, Vanessa. 2011. “Investigating the Web Search Behaviours of Translation Students: An Exploratory and Multiple-Case Study.” PhD diss., Universitat Ramon Llull.

- Enríquez Raído, Vanessa. 2014. Translation and Web Searching. New York: Routledge.

- Fisher, Karen E., Sanda Erdelez, and Lynne McKechnie. 2006. Theories of Information Behavior. Medford: Information Today.

- Gouadec, Daniel. 2007. Translation as a Profession. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gough, Joanna. 2016. “The Patterns of Interaction between Professional Translators and Online Resources.” PhD diss., University of Surrey.

- Gough, Joanna. 2017. “Investigating the Use of Resources in the Translation Process.” In Trends in E-Tools and Resources for Translators and Interpreters, edited by Gloria Corpas Pastor, and Isabel Durán-Muñoz, 9–36. Leiden: Brill Rodopi.

- Gough, Joanna. 2019. “Developing Translation-Oriented Research Competence: What Can We Learn from Professional Translators?” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 13 (3): 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1656404.

- Hansen, Gyde. 2013. “The Translation Process as Object of Research.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Carmen Millán, and Francesca Bartrina, 88–101. London: Routledge.

- Heinström, Jannica. 2006. “Broad Exploration or Precise Specificity: Two Basic Information Seeking Patterns among Students.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (11): 1440–1450. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20432.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo. 2017. Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hvelplund, Kristian Tangsgaard. 2017. “Translators’ Use of Digital Resources during Translation.” HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business 56: 71–87. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i56.97205.

- Hvelplund, Kristian Tangsgaard. 2019. “Digital Resources in the Translation Process–Attention, Cognitive Effort and Processing Flow.” Perspectives 27 (4): 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1575883.

- Kohnen, Angela M., and Gillian E. Mertens. 2019. “‘I’m Always Kind of Double-Checking’: Exploring the Information-Seeking Identities of Expert Generalists.” Reading Research Quarterly 54 (3): 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.245.

- Kromme, Christian. 2017. Humanification – Go Digital, Stay Human. The Choir Press.

- Kuznik, Anna, and Christian Olalla-Soler. 2018. “Results of PACTE Group’s Experimental Research on Translation Competence Acquisition. The Acquisition of the Instrumental Sub-Competence.” Across Languages and Cultures 19 (1): 19–51. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.1.2.

- Massey, Gary, and Maureen Ehrensberger-Dow. 2011. “Investigating Information Literacy: A Growing Priority in Translation Studies.” Across Languages and Cultures 12 (2): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.12.2011.2.4.

- Nord, Britta. 2009. “In the Year 1 BG (before Google): Revisiting a 1997 Study Concerning the Use of Translation Aids.” In Translatione via Facienda. Festschrift Für Christiane Nord Zum 65. Geburstag, edited by Gerd Wotjak, 203–217. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Palmer, Judith. 1991. “Scientists and Information: I. Using Cluster Analysis to Identify Information Style.” Journal of Documentation 47 (2): 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026873.

- Pinto, Maria, and Dora Sales. 2008. “INFOLITRANS: A Model for the Development of Information Competence for Translators.” Journal of Documentation 64 (3): 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810867614.

- Pinto, María, Javier García-Marco, Dora Sales, and José Antonio Cordón. 2010. Interactive Self-assessment Test for Improving and Evaluating Information Competence. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36 (6): 526–538. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.08.009.

- Pinto María, Francisco Javier García Marco, Ximo Granell, and Dora Sales. 2014. “Assessing Information Competences of Translation and Interpreting Trainees: A Study of Proficiency at Spanish Universities Using the InfoliTrans Test.” Aslib Journal of Information Management, 66: 77–95.

- Pym, Anthony. 2010. Text and Risk in Translation. Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group Universitat Rovira i Virgili. http://usuaris.tinet.cat/apym/on-line/translation/risk_analysis.pdf.

- Rowlands, Ian, David Nicholas, Peter Williams, Paul Huntington, Mmaggie Fieldhouse, Barrie Gunter, Richard Withey, Hamid R. Jamali, Tom Dobrowolski, and Carol Tenopir. 2008. “The Google Generation: The Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future.” Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives 60 (4): 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530810887953.

- Sales, Dora, and Maria Pinto. 2011. “The Professional Translator and Information Literacy: Perceptions and Needs.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 43 (4): 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000611418816.

- Shih, Claire Y. 2019. “A Quest for Web Search Optimisation: An Evidence-Based Approach to Trainee Translators’ Behaviour.” Perspectives 27 (6): 908–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1579847.

- Spink, Amanda, and Jannica Heinström. 2011. Library and Information Science: New Directions in Information Behaviour. Bingley: Emerald Insight.

- Summerfield, Richard. 2013. “The Rise of the Digital Currency.” Financier Worldwide. https://www.financierworldwide.com/the-rise-of-the-digital-currency#.ZDbLZXbMIuU.

- Sycz-Opoń, Joanna Ewa. 2021. “Trainee Translators’ Research Styles: A Taxonomy Based on an Observation Study at the University of Silesia, Poland.” The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research 13 (2): 136–163. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.113202.2021.a08.

- Szalma, James L. 2009. “Individual Differences in Human–Technology Interaction: Incorporating Variation in Human Characteristics into Human Factors and Ergonomics Research and Design.” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 10 (5): 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639220902893613.

- Uher, Jana. 2018. “Taxonomic Models of Individual Differences: A Guide to Transdisciplinary Approaches.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 373:20170171. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0171.

- White, Ryen W., and Steven M. Drucker. 2007. “Investigating Behavioral Variability in Web Search.” 16th International World Wide Web Conference, WWW2007, 21–30.

- Zhang, Li-fang, and Robert J Sternberg. 2005. “A Threefold Model of Intellectual Styles.” Educational Psychology Review 17 (1): 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-1635-4.

- Zhang, Li-fang, Robert J. Sternberg, and Stephen Rayner. 2012. Handbook of Intellectual Styles: Preferences in Cognition, Learning, and Thinking. New York: Springer.