ABSTRACT

The resilience approach has recently emerged as a new topic of EU foreign policy debates and research. This paper adopts a complexity theory perspective to analyze the operationalization of the resilience approach in the EU response to crisis in Ukraine during 2014–2021. Building upon this theory, this paper distinguishes between resilience-as-quality of a complex system and resilience-as-thinking about a complex system. The empirical analysis focuses on the complexity features of non-linearity and self-organizing localization of EU interventions undertaken in the framework of the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP). It concludes that the emerging system of intervention displays some complexity qualities, yet the EU crisis response follows the linear and top-down logic embedded in the project-based practices.

1. Introduction

The resilience approach is considered as one of the key developments in the evolution of the EU foreign policy doctrines. Resilience emerged as a central concept in the EU Global Strategy (EUGS) (High Representative/Vice-President Citation2016) after being included in the EU development and humanitarian aid policies (European Commission Citation2012, Citation2013; Council of the European Union Citation2013) and European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) (European Commission/High Representative Citation2015). The broad initial understanding of resilience as ‘the ability of an individual, a household, a community, a country or a region to withstand, to adapt, and to quickly recover from stresses and shocks’ (European Commission Citation2012, 5) was subsequently summarized in the EUGS as ‘the ability of states and societies to reform, thus withstanding and recovering from internal and external crises’ (High Representative/Vice-President Citation2016, 23). As explained by the EUGS penholder, resilience constituted an integrating policy concept that provided ‘a common lexicon across policy communities’ of compartmentalized domains of EU foreign policy (Tocci Citation2020, 178).

The adoption of EUGS catalyzed a new wave of research on the strategic outlook of EU foreign policy, given both the innovative process of its elaboration and its policy content, arguably setting new directions for EU foreign policy (Tocci Citation2017; Morillas Citation2019). Resilience as a ‘novel discourse’ was considered a potential paradigm-shift for existing EU foreign policy practices in general (Juncos Citation2017) and a source for another change in the ENP (Korosteleva Citation2020a). Doctrinal change would come from adopting a new post-liberal thinking about external interventions that should empower local self-governance of communities and emphasize their internal capabilities and capacities to face the conditions of contemporary uncertainties and complexity (Chandler, Citation2014; Juncos Citation2017; Korosteleva, Citation2020a). However, other contributions were more skeptical about the EU approach to resilience given its adaptation to the existing liberal EU paradigm supporting external interventions to spread universal solutions to emerging threats (Joseph and Juncos, Citation2019; Wagner and Anholt Citation2016). Indeed, some early assessments of the implementation of the resilience approach suggest that the rise of the resilience narrative in policy documents hardly changed previous policy practices (Petrova and Delcour Citation2020; Romanova Citation2019). Despite the obvious inspiration of resilience conceptualization in complexity thinking, an analysis of complexity features is a rarely explored perspective to better understand the approach to resilience in the EU policy.

This paper investigates the extent to which the EU has embraced a genuine resilience approach as envisaged by complexity thinking in its crisis response and peacebuilding interventions. Complexity theory in natural and social sciences examines the constitution and evolution of systems as self-organizing emergent phenomena evolving in a non-linear way (Mitchell Citation2009; Morçöl Citation2012). It has been argued that complexity thinking underpins resilience in liberal and post-liberal approaches, yet in significantly different ways (Chandler Citation2014, 19–69). ‘Simple complexity’ thinking underpinning the (neo-)liberal approach to resilience stresses an exogenous perspective on the support for adaptation of closed systems in view of adversities. ‘General complexity’ thinking of the post-liberal approach to resilience stresses on emergent processes of relational adaptation in evolving systems without subject-object hierarchies (Chandler Citation2014, 27–28).

To address the operationalization of resilience by the EU, this paper distinguishes between resilience-as-quality of a complex system and resilience-as-thinking about a complex system based on differences between ‘simple’ and ‘general’ complexity thinking (Chandler Citation2014; Korosteleva and Flockhart Citation2020). To analytically operationalize this distinction, the paper assesses the presence of complexity features in the specific practices embedded in these interventions and quality of the overall system emerging from the set of EU peacebuilding interventions . In this way, it illustrates that the incipient emergence of resilience-as-quality in the peacebuilding landscape does not originate from, nor is translated into, resilience-as-thinking about the interventions. Therefore, the apparent persistence of a liberal resilience approach leads to the absence of genuine local self-organization and non-linearity in the practices of EU peacebuilding interventions. Even though the emerging system of intervention displays some complexity qualities as rather unintended consequences of the intensity of the EU involvement in Ukraine, resilience in the EU crisis response follows a linear and top-down logic embedded in the project-based practices.

To illustrate this argument, the paper traces the complexity features in the practices of interventions and the emerging system of the EU crisis response interventions in the crisis in Ukraine during 2014–2021. The crisis in Ukraine is significant in this context since it constituted an influential context for policy deliberations on the renewed ENP and EU Global Strategy (Tocci Citation2017). Russia’s occupation of the Ukrainian Peninsula of Crimea and active support toward the upheaval in the Eastern Ukrainian region of Donbass constituted a major conflict in Europe. As a result, the EU intervened with a multidimensional strategy to support the new Ukrainian authorities and stabilize the conflict in Eastern Ukraine (Youngs Citation2017). This case also captures whether complexity informed resilience shaped the EU approach to Ukrainian local actors active in peacebuilding efforts (Bazilo and Bosse Citation2017; Kyselova Citation2017) and facilitated the process of peacebuilding aimed at creating the space for local societies rather than interfering too much and undermining self-organizing processes necessary for resilient societies (De Coning Citation2016b).

The focus of this analysis is on 19 European Commission Decisions adopting Exceptional Assistance Measures (EAMs) undertaken in the framework of the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP). The very purpose of the IcSP is to support EU external policies in the areas of ‘crisis response, conflict prevention, peacebuilding and crisis preparedness, and in addressing global and trans-regional threats’ (European Union Citation2014, Art. 1.1). This instrument provides the most direct response to the conflict in Ukraine with the aim of contributing to the alleviation of its consequences. Other resources employed by the EU in Ukraine, within the framework of the European Neighbourhood Instrument, supported state-level institutional agenda of policy reforms to facilitate the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement commitments rather than any direct consequences of war. The only exception was the program EU4ResilientRegions adopted in 2020 focusing on the Eastern and Southern parts of Ukraine with the aim of enhancing their overall resilience and peacebuilding capacity (European Commission Citation2020).

The remainder of the paper proceeds in four sections. Section 2 presents the analytical perspective on the resilience approach emerging from complexity thinking. Section 3 introduces the practices embedded in the IcSP interventions in response to the crisis in Ukraine to assess the complexity features and presence of resilience-as-thinking. Section 4 shows the incipient emergence of resilience-as-quality in the EU intervention in the framework of IcSP in response to the crisis in Ukraine. The final section summarizes the findings and outlines further lines of research.

2. Resilience as a feature of complex social systems

Resilience has become a key conceptual point of reference in the research and practice of international politics. Following Bourbeau (Citation2018, 3), resilience can be defined as ‘the process of patterned adjustments adopted in the face of endogenous or exogenous shocks, to maintain, marginally modify, or to transform a referent object’. It implies the study of reactions to critical events and phenomena. It suggests that these critical phenomena for resilient actors do not lead to fatal collapse. Therefore, resilience in conflict and peace research can be understood as ‘the ability of individuals or a community to cope with or adapt to violent conflicts in order to foster a more sustainable peace’ (Joseph and Juncos Citation2020, 289) or more broadly as ‘the ability of social institutions to absorb and adapt to the shocks and setbacks they are likely to face’ (De Coning Citation2016a, 29).

The distinction between resilience-as-quality and resilience-as-thinking (Korosteleva and Flockhart Citation2020; Chandler Citation2014) captures very well the descriptive and performative aspects of this concept. On the one hand, resilience-as-quality describes general features of entities, such as systems, organizations, and agents. In this approach, resilience characterizes such an entity by ‘having necessary elements in place that can facilitate reflexivity and self-organization, to amplify an entitys’ inherent strength, awareness of the outside (Anthropocene) and its purpose and ambition’ (Korosteleva and Flockhart Citation2020, 158). Resilience-as-thinking enables ‘governing to become more reflective and adaptive’ through prioritizing self-governance at local and individual levels (Korosteleva and Flockhart Citation2020, 159). It empowers agents with inherent abilities to adapt and learn from within to maintain their vital functions in view of adversities.

Such a conceptualization of resilience is associated with complexity thinking (Chandler Citation2014; De Coning Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Complexity is a heterogeneous interdisciplinary approach to natural and social sciences that focuses on the constitution and evolution of systems (Mitchell Citation2009; Morçöl Citation2012). Complex is ‘a system in which large networks of components with no central control and simple rules of operation give rise to complex collective behaviour, sophisticated information processing, and adaptation via learning or evolution’ (Mitchell Citation2009). De Coning (Citation2016a, 20) defines complexity as a way of thinking and perceiving reality from a systemic perspective that

refers to a particular type of system that has the ability to adapt, and that demonstrates emergent properties, including self-organising behaviour. It comes about, and is maintained, as a result of the dynamic and non-linear interactions of its elements, based on the information available to them locally, and as a result of their interaction with their environment, as well as from the modulated feedback they receive from the other elements in the system.

Complexity theory translated into the field of International Relations emphasizes distinct ontological and epistemological premises for thinking about international politics (Kavalski Citation2007; Jervis Citation1997; Bousquet and Curtis Citation2011). Relational ontology (Kurki Citation2020; Jackson and Nexon Citation1999) stresses continuously self-organizing, adapting, and co-evolving global system, nested in and organically connected to sub-systems and networks of interacting units. The emergence of such entangled systemic forms is non-linear and uncertain.

Complexity insights offer a comprehensive theoretical framework by taking a holistic systemic perspective on peace and conflicts in societies. They develop insights that challenge different approaches to liberal peacebuilding, prescribing universalistic solutions to conflicts (Richmond Citation2006, Citation2010; Paris Citation2010; Chandler Citation2014). Instead, complexity theory emphasizes deep uncertainty as an intrinsic quality of social systems, which limits our ability to prescribe exogenous solutions to conflicts. Therefore, the debates about whether a liberal peace approach works better should consider that the behavior of complex social systems is difficult to control and predict; hence, it is impossible to apply any universal recipes for peace (de Coning, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). In contrast to liberal approaches, complexity theory stresses bottom-up self-organization as a precondition to sustainable peace, opposed to any external solutions based on pre-designed doctrines.

The resilience approach depends on the acknowledgment of world complexities since ‘without complexity there would be no demand for resilience’ (Chandler Citation2014, 19). Following this understanding, the resilience approach , one the one hand, is the awareness of complexity of governance and, on the other hand, emerges from embracing complexity thinking in practice (Chandler Citation2014). Building upon simple complexity thinking, the liberal approach to resilience focuses on the capacities of subjects to withstand external shocks. This liberal approach is considered reductionist and tends to be associated with top-down linear causalities and responsibilities within a system that is exogenous to the governing actor (Chandler Citation2014, 27). The post-liberal approach to resilience emphasizes the ongoing participatory and self-organizing processes empowering local agents (Korosteleva Citation2020b). For such resilience to emerge, practices embrace and enhance the complexity of a social system featuring non-linear causality and localization. Resilience in thinking arises from self-organizing bottom-up practices rather than from the hierarchically imposed liberal policy ideal (Chandler Citation2014, 27). As argued by De Coning Citation2016a, 29), ‘from this perspective peacebuilding should be about stimulating and facilitating the capacity of societies to self-organize, so that they can develop their own resilience and internal complexity’.

Complexity thinking appears in resilience approach in two distinct ways. In the first place, resilience-as-thinking is reflected when such complexity thinking informs the practices of interventions. Practices might be defined as ‘temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed nexus of doings and sayings’ (Schatzki Citation1996, 89), giving equal importance to speech acts and human actions. Therefore, besides speech acts, the study of practices looks at repetitive performances as an expression of tacit background knowledge reflecting human thinking. To study them, the focus is on repetitive patterns in ‘a routinized type of behaviour which consists of several elements interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, “things” and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotions and motivational knowledge’ (Reckwitz Citation2002, 249).

In the second place, the relations between specific interventions might display complexity features characterizing resilience-as-quality. The representation of aggregated causal relations between actors and objectives of interventions might visualize an emerging system of interventions. A system is a performing arrangement of relations between elements displaying holistic properties. The following features characterize complex systems: 1) the interdependence of the group of elements of the system with holistic properties that are more than a sum of the properties of its elements, 2) nonlinear relations, and 3) openness to the external environment (Morçöl Citation2012, 48). Networks analysis is a popular method of analysis in the study of complex systems since it captures an emerging system of relations where different elements are interdependent (Morçöl Citation2012, 210–221).

To assess complexity thinking in the EU crisis response in Ukraine in the practices of intervention and emerging system of interventions, we will analyze the manifestations of two interdependent complexity features: 1) nonlinear causal processes such as feedback loops and equifinality and 2) sensitivity to local self-organization and non-imposition of central control. Non-linear causal processes are fundamental features of complex social systems. A complex systemic effect emerges from the relational dynamics between different elements rather than as a sum of individual features or actions. The emergence of complex macro system properties is not reducible to individual micro factors given that the relations between properties are disproportional. Disproportionality means that there is a permanent imbalance between different observable elements: small changes may have big effects, big changes may have small effects; or effects come from unanticipated factors (Morçöl Citation2012, 28). The relations between elements in a complex system are dynamically asymmetrical and it is difficult to anticipate cause-and-effect paths (De Coning Citation2016a, 22–23). Non-linear causality implies that systemic effects are attributed to multiple, multi-level causal variables simultaneously and causal relations are multidirectional and/or circular. In practice, it leads to the study of positive and negative causal feedback loops (Morçöl Citation2012, 206–209), and equifinality causal paths (Kapsali Citation2013).

Localization as a feature of resilience from a complexity perspective is associated to the phenomenon of self-organization (De Coning, Citation2016a). Self-organization means that the regulation of interactions takes place from a bottom-up perspective as a spontaneous phenomenon, and it exhibits sustaining patterns without central authority or controlling agents. As argued by Cilliers (Citation1998, 90), self-organization of complex systems is a property ‘which enables them to develop or change internal structure spontaneously and adaptively in order to cope with, or manipulate, their environment’. Self-organization is associated with endogenous and autonomous causes of systemic processes rather than exogenous causes; however, it does not mean that it develops in isolation from the environment.

Building upon this conceptual discussion, the next two sections analyze the extent to which nonlinear causal processes and sensitivity to local self-organization inform EU peacebuilding interventions in Ukraine. First, the analysis of the practices of intervention in Ukraine looks at the discursive framing and organizational scripts underpinning them. Second, the emerging system of EU interventions is analyzed from the perspective of networks of relations between different elements of these interventions.

3. Resilience-as-thinking in the EU peace-building interventions

This section assesses resilience-as-thinking by analyzing complexity features in EU peace-building practices in Ukraine. It analyzes whether the EU approach reflects non-linearity and localized self-organization, both in the documents framing the interventions in Ukraine and in the organizational practices of preparing and implementing the interventions on ground.

3.1 Resilience thinking in EU statements

The EU approach on resilience is founded on a general acknowledgement of the complex qualities of the international system. Complexity awareness features in many EU strategic documents, such as the EU comprehensive approach to external conflicts and crises (European Commission/High Representative Citation2013), the European External Action Service strategic assessment (Council of the European Union Citation2015), the ENP (European Commission/High Representative Citation2015), and EUGS (High Representative/Vice-President Citation2016). For example, the Eastern Partnership Riga Summit mentioned ‘the importance of strengthening the resilience of Eastern European partners faced with new challenges for their stability’ (Eastern Partnership Citation2015), and the renewed ENP (European Commission/High Representative Citation2015) included a few mentions of resilience. However, in both cases the concept of resilience is presented as an instrument to preserve the integrity of states in view of crises rather than an avenue to empower communities affected by destabilizing violence and threats.

The EaP summit in 2017 reaffirmed ‘the importance of strengthening state, economic and societal resilience both in the EU and the partner countries’ (Council of the European Union Citation2017, 2). The ambition of ‘strengthening our common resilience’ (Council of the European Union Citation2017, 11) also framed the pursued deliverables in policy areas of economy, governance, connectivity, and society, together with targets for the cross-cutting issues of gender, civil society, media and strategic communication adopted during this summit. Resilience was declared again as ‘an overriding policy framework’ towards Eastern Partnership partners in a March 2020 Joint Communication (European Commission/High Representative Citation2020; Council of the European Union Citation2020). However, mentions to resilience did not, until 2021, have a clear translation into changes in the areas of cooperation, objectives, mechanisms, and instruments of the EaP. Therefore, resilience might be seen as another rhetorical device rather than a novel policy approach.

Finally, despite these general declarations, resilience did not appear explicitly in the framework of EU–Ukraine relations in general or in the EU response to the crisis in Ukraine until late 2021. The EU response to the crisis in Ukraine involved numerous political, diplomatic, economic and developmental measures. The EU provided generous emergency economic measures to support the extremely fragile Ukrainian economy, deployed a special CSDP (Common Security and Defence Policy) mission to Ukraine, finalized the process of entering into force of the Association Agreement, sent special experts’ missions to support Ukrainian reforms, and introduced sanctions against Russia and separatist entities (Youngs Citation2017; Karolewski and Davis Cross Citation2017; Natorski and Pomorska Citation2017). However, the dominant framing of EU policy toward the crisis in Ukraine was stabilization and de-escalation along with enhanced EU-Ukraine cooperation, rather than resilience (Natorski Citation2020). In this general framing, the EU emphasized a top-down coercive approach to conflict management marginalizing local perspectives. The ideas of ensuring full protection of minority rights, including linguistic rights, and the decentralization in Ukraine presented as ways to address bottom-up sensitivities in post-Maidan Ukraine were contested, as they were considered to be as a way to deteriorate Ukraine national cohesion and, as a result, they remained marginal in the overall state-level focus of the EU policy. Only the approval of a new Multiannual Indicative Programme for Ukraine for 2021–2027 emphasized resilience across economic, institutional, security, environmental, climate, digital, and societal domains (European Commission Citation2021). However, these plans were abruptly disrupted by the Russian military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

3.2 The logic of cause-effect linearity in IcSP interventions

The European Commission adopted 19 Decisions approving Exceptional Assistance Measures during 2014–2020 in the framework of the IcSP (see Annex 1) to support peacebuilding and stabilization in Ukraine.Footnote1 Within these 19 Decisions, we identified 29 different interventions in total, which is our unit of analysis.Footnote2 Interventions are projects consisting of distinctive activities, target groups and beneficiaries, budget, expected results, and specific objectives, eventually sharing with other interventions only a general rationale, overall objectives, and assumptions.Footnote3 They are the most encompassing expression of direct EU peacebuilding efforts in Ukraine. However, following the general trend, only three Decisions (on civilian protection, de-mining, and socio-economic data in the Azov Sea region) explicitly mentioned resilience in their titles and only two Decisions (on community-led peacebuilding and the reintegration of veterans; and on counteracting disinformation) included resilience in their general objectives. Such absence of in-depth resilience thinking is not surprising given that the process of planning of these projects does not reflect the complexity features underpinning resilience thinking.

The planning of IcSP projects follows standardized process codified in the so-called Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) Manual (European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments Citation2018b). This organizational handbook specifies predefined procedures and templates for planning projects within the FPI Services of the European Commission that are in charge of managing IcSP. The detailed methodology follows the managerial technocratic tools of Project Cycle Management and displays a linear thinking, envisaged in the sequence of pre-defined actions. In general, IcSP interventions constitute a defined set of patterned and planned activities to accomplish some unique goals and ambitions within a fixed period and with the limited resources available. Given these standardized pre-defined qualities, EU development projects might be considered as an expression of an embedded neo-liberal technocratic approach to deliver support to other countries (Kurki Citation2011), which does not support complexity features of non-linearity and localization.

The backbone of project planning and management in the EU practices of designing peacebuilding interventions is the so-called Theory of Change (ToC) approach (European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments Citation2018b). The ToC is associated with policy evaluation practices aimed at uncovering causal relationships between public policies and their effects. Such kind of program theories are ‘more modest than fully fledged social science theories’ (Knill and Tosun Citation2012, 186). The ToC as a practical analytical tool is widely employed by practitioners in the development and peacebuilding fields to plan interventions and it is ‘a set of beliefs about how change happens’ (Church and Rogers Citation2006, 11). Based on individual and organizational experiences and following standardized procedures of participatory analysis, the ToC focuses on the critical analysis of cause-and-effect relations and assumptions underpinning a process of accomplishing desired short-term (outcomes) and mid-term (impact) effects of intervention. The ToC may picture apparently linear relations between inputs, outputs, outcomes and impact. Usually, this thinking tends to be summarized in the simple hypothetical belief of causality that ‘if some results (outputs) are accomplished, then some effects (outcomes) will be produced’ (Stein and Valters, Citation2012). While this approach may be also employed ‘to explore and represent change that reflects more complex and systemic understanding of development, rather than portraying a linear process’ (James Citation2011, 3), the practice of designing the ToC in the IcSP project displays a clearly linear approach to cause-effect relations.

All 19 European Commission Implementing Decisions and annexed EAMs Action Fiches that were analyzed provide very similar comprehensive and comparable information about the institutionalized beliefs on the cause-and-effect relations in specific projects since they follow the same template (European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments Citation2018a). As a result, they identify the ‘why, what, who, when and how’ of the intervention by including standard sections summarizing the action, its background and rationale, risks and assumptions, overall and specific objectives, actions components and expected results, implementation modalities, organizational set-up, monitoring and evaluation and complementarity and coordination with other actions. The logic of these actions is based on the cascading effect of specific activities that will contribute to the accomplishment of short- and long-term effects. In this way, the analyzed documents also offer comparable and accurate information about the design framework for the implementation practices and consequently establish the boundaries for the implementation of the resilience approach in practice. Given that any significant deviations would require the approval of the European Commission, it is highly probable that implementation practices follow the initial design included in the analyzed documents.

3.3. The logic of top-down thinking about stakeholders in IcSP interventions

The standardized process of preparation and implementation of the IcSP exposed in the institutional handbook also illustrates that the process of localization and self-organization empowerment does not feature as a part of the organizational methodology (European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments Citation2018b). The process of involvement of different stakeholders in EU interventions is decided by the staff of the European Commission (FPI Project Managers) and the EEAS, both in the headquarters in Brussels and EU Delegations. For example, as a part of the process of identifying a possible project, the analysis of possible stakeholders is conducted based on the pre-defined needs that should correspond to the EU strategy and specific mandate (Ibidem, p. 52). Indeed, the specific objective of IcSP is, among others, to contribute ‘swiftly to stability by providing an effective response designed to help preserve, establish and re-establish the conditions essential for the proper implementation of Union’s external policies’ (European Union Citation2014, Art. 1.4.a). Therefore, the consideration of possible stakeholders only depends on whether they are ‘involved in the needs or in their resolution’ (European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments Citation2018b, 57). The description of such ‘needs’ to be addressed in an IcSP project is conducted by EU staff employing several analytical tools such as ‘Political Economy Analysis’, ‘Conflict analysis’, ‘Cultural dimensions analysis’ and ‘SWOT analysis’.

Following such outside-in analysis, consulted stakeholders ‘validate that all the different perspectives and points of view have been taken into account in the context analysis and that the needs identified correspond to the reality and are the ones that matter’ (Ibidem, p. 68). Such analysis also determines the roles of different stakeholders ‘because they are a part of the problem and/or a part of the solution’ (Ibidem, p. 68). Furthermore, a separate process of ‘stakeholder analysis’ exogenously identifies those actors that can provide further information for the intervention and eventually become part of the implementation plan. Stakeholders might be any actors interested or affected by the intervention and there is no clear indication that local actors should be prioritized (Ibidem, p. 68–77). As a result, all 29 analyzed EU interventions in Ukraine do not report any genuine process of consultations that would reflect a space for embracing local concerns and priorities. The reported rationales of interventions indicate standardized narratives and that many project ideas emerged from different types of studies and reports, frequently for other International Organizations, central administration prioritiesand preparatory field missions of EU staff.

Similar deficits in terms of the localization and self-organization approaches dominate in the phase of project implementation. The analysis of the design of all 29 intervention suggests traditional activities of training and the provision of equipment for local agents. In several projects, the idea of more community-led activities involves some transfer of skills and knowledge under supervision of external actors rather than support for self-organization of local actors to pursue their endogenously developed initiatives. Moreover, state institutions such as Ministries appear as a key point of reference to be empowered with means for building their capacity to inform and organize their stakeholders, as well as gain awareness about relevant information to transfer them later for the benefit of other local target groups and local populations as a final beneficiaries.

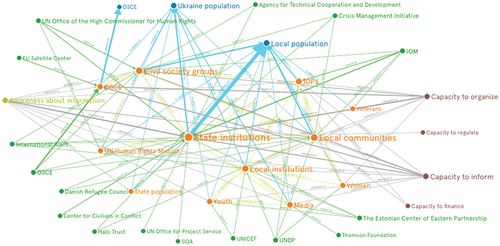

The interventions follow the EU institutional script in terms of the proposed approach, objectives, procedures and involved actors, while the involvement of the Ukrainian side is limited to the reception of the proposed projects, which remain managed by the EU Delegation in Kyiv. At the same time, however, while the EU remains the ultimate controlling agent hierarchically supervising other actors, it also shows its strong dependence on other implementing actors. Many implementing actors (green in ), in particular, other international organizations such as Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), International Organization for Migration (IOM), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) are highly specialized to perform the tasks defined by the EU. The EU provides material and technical support to the observation of ceasefire by the OSCE, support for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) by the IOM, and engagement with local communities by UNDP, given that these organizations can quickly mobilize the expertise and their local networks to perform the expected activities. In particular, the highly autonomous role of OSCE in all ceasefire monitoring activities benefited from the EU support, but the EU does not control these activities since the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission depends on OSCE’s mandate. While the EU, as a key financial provider, plans and controls different interventions, each intervention depends on the implementers rather than on the hierarchical imposition by the EU supervising officer. Nevertheless, local initiatives remain hierarchically dependent on external actors providing pre-defined assistance.

4. Resilience-as-quality in an emerging system of EU interventions in Ukraine

This section focuses on resilience-as-quality by analyzing the complexity features in the emerging network of connections and causalities between the aggregated elements of the ToC embedded in project Action Fiches of 29 IcSP EU interventions. The analysis of codified information about post-crisis needs, means, and involved actors visualizes the rather incipient nature of non-linearity and local self-organization.Footnote4

4.1. Non-linearity in the EU interventions

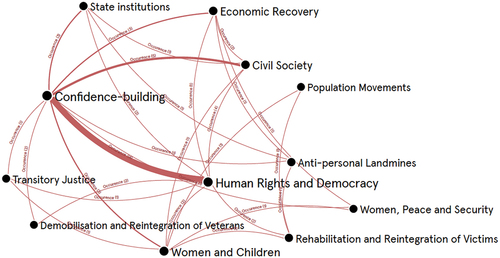

The feature of equifinality of EU interventions is already implied in the legal basis. The IcSP distinguishes 17 different technical and financial assistance areas in response to a situation of crisis or emerging crisis (art. 3.2 of Regulation), which can be combined in different configurations with the very aim of contributing to stability in a situation of crisis or emerging crisis to facilitate the implementation of EU external policies. Each Exceptional Assistance Measure may combine different technical areas without any specific limitations. The analyzed 19 Commission Decisions include 10 types of assistance in different configurations. Only one case has only one type of assistance (anti-mines action), while in other cases there is a combination of different types of assistance. On average each Decision involves three types of assistance. The co-occurrence of different formal bases of intervention for each of the External Assistance Measures illustrates two features of equifinality from a complexity perspective ().

On the one hand, based on the degree of centrality measurement, there are three key assistance nodes: confidence-building (nine connections), human rights and democracy (eight connections) and women and children (seven connections). A central axis of assistance is the support for international and regional organizations, the State and civil society actors to promote confidence-building, mediation, dialogue and reconciliation (European Union Citation2014, Art. 3.2 a); and to the support for promotion and defense of human rights and fundamental freedoms, democracy, and the rule of law (European Union Citation2014, art. 3.2 m). The confidence-building assistance appears in 16 Decisions and 14 times in conjunction with the promotion of human rights and democracy. In addition, both types of assistance co-occur frequently (five and four times, respectively) with the assistance in benefit of civil society organizations, including independent media.

On the other hand, however, this central axis co-exists with numerous adjacent types of assistance constituting a network of interrelated fields of assistance. The relationship between these different nodes shows a relevant degree of systemic interconnectedness and interdependence between different assistance measure types. The equally distributed degree of centrality of measures in support of women and children (7), civil society (5), economic recovery (5), rehabilitation and reintegration of victims (4), anti-personal landmines (4), and state institutions (4) shows a high degree of diversity of planned measures.

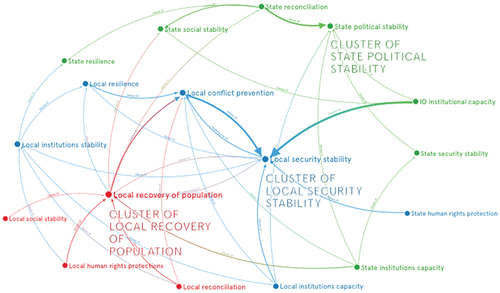

Non-linear features, such as feedback loops and equifinality are displayed to some degree in the interconnections between specific and overall objectives and assumptions and risks of each EU intervention codified as post-crisis security, politico-economic or social needs corresponding to different types of peacebuilding approaches (Richmond Citation2006; Richmond, Björkdahl, and Kappler Citation2011; Natorski Citation2011). Security needs are coded as security stability or conflict prevention; politico-economic needs as political stability, institutional stability, institutional capacity, institutional commitment, and economic recovery; and social needs as social stability, resilience, reconciliation, and human rights protection.

The relations between them illustrate the emergence of an expanding and interconnected system of EU interventions in Ukraine. One intervention suggests rather simple linear cause-effect relationships between specific objectives and overall objectives, but the connections established between the different crisis needs (nodes of the network) of all 29 interventions (see ) show an emerging and cumulative network of relationality and interdependence between the accomplishment of different needs constituted over time. At the same time, however, the distribution of connections between different needs is uneven. The local recovery of population, local security stability, local conflict prevention, local institutions stability, and state political stability nodes occupy central positions, both in terms of degree of centrality and betweenness between different nodes. In equifinality terms, different crisis needs have different weights as, for example, the need of local conflict prevention can be accomplished through six other needs, such as local recovery of population or local reconciliation.

Nevertheless, shows only two feedback loops where different needs are directly and mutually dependent: 1) local conflict prevention and local security stability and 2) local security stability and local recovery of population. In addition, there are two more developed feedback loops involving the relations between the nodes of local recovery of population, resilience, conflict prevention, and security stability and the nodes of local institutions stability, resilience, conflict prevention and security stability. These five nodes feature the highest degrees of centrality in this network together with the node of state political stability.

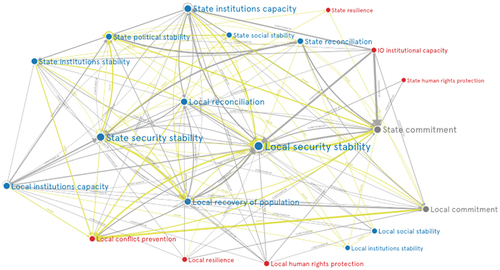

Following this simple cause–effect relationship between needs, elaborates more on non-linear causal relations by introducing the distinction between the relations of causality and conditionality between different crisis needs. Action Fiches include a section of assumptions that specify pre-conditions external to the intervention that are at the same time conditioning the successful implementation of an intervention. Therefore, with the introduction of this factor codified also as crisis needs, the causal logic is that an accomplishment of a need X conditioned by the presence of a need Y, will contribute to the accomplishment of a need Z. As a result, as visualized in , the same crisis need can have three different roles in a network of causal chains of an intervention and be internal or external to the intervention itself. With the introduction of the distinction between the needs as assumptions and needs as objectives, the connections between different needs increased significantly. In fact, only two needs (state and local commitment) appeared as an assumption for the interventions and not a direct or indirect objective. As a result, the non-linearity in terms of feedback loops and equifinality increases as well.

Both state and local security stability are two central nodes in the networks of causalities of the system of EU intervention in response to the crisis in Ukraine. Both are frequently self-referential since an assumption of local/state stability is expected to increase further local/state stability, but they are also connected in different ways to other post-crisis needs displayed in the EU interventions. The high degree of centrality of these nodes reflects that they are both an effect and a cause for other effects in causality chains. As a result, the number of feedback loops emerging from the causal connection between different nodes increased significantly. For example, the need of local security stability depends directly on 10 simple feedback loops, the need of state security stability depends on 7 simple feedback loops and the need of local recovery of populations depends on 6 simple feedback loops. Therefore, the density of interconnectedness between different needs is very high. Moreover, given the density of connections between different nodes and their different roles in causal chains, the number of multipart feedback loops is also significant. The in- and out-centrality degrees are significant for many networks nodes. In total, 10 nodes have 8 or more of in-degree centrality connections and 9 nodes have 8 or more of out-degree connections.

4.2. Localization and self-organization in EU interventions

The nature of the sensitivity to localization of post-crisis needs in Ukraine and space for self-organization in EU interventions is significantly more ambiguous. The networks of relations between different crisis needs distinguish local and state levels to verify localization sensitiveness to specific needs. Both illustrate very clearly the co-existence and close interrelation of both levels in planned interventions. The EU interventions displayed significant sensitivity to the local nature of post-conflict needs while focusing also on the state level nature of these needs. For example, the network in illustrates concentration on localization in terms of accomplishing security stability, recovery of population and conflict prevention. However, shows that the interdependence between state and local levels is very strong. There is significant cluster symmetry between state and local levels since four key clusters are state andlocal security stability and state andlocal institutions capacities respectively. Therefore, the local aspects of different needs are embedded in and connected to a broader state-level network of causalities between different levels of needs.

The above-mentioned ambiguities related to localization sensitivity and support for self-organization can also be observed by analyzing the involvement of actors distinguished (see ) between the target groups (orange), the beneficiary (blue), and the implementers (green). Target groups are actors directly affected by an intervention as recipients of means to address existing needs. They are codified as institutions (local, state), society (civil society, IDPs, veterans, women, media youth, and local communities) and two specific international organizations (OSCE and UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission). The codification of a local population as a final beneficiary emphasizes the localized nature of benefiting communities, while codification of the Ukraine population as a final beneficiary suggests very generic not-localized state-wide nature of societal actors benefiting from an intervention in the long term. Finally, implementers – specific actors hired to undertake activities – were codified also in terms of international, state, and local governmental or non-governmental entities.

The network of relations between these actors can be summarized as a flow of influence originating from international actors as implementers to either state institutions or local actors as targets groups to benefit the local or the whole Ukraine population as final beneficiaries. All implementers of projects are international actors, either recognized international organizations or transnational specialized NGOs. They engage with different target groups by linking local and state levels. Significant efforts to localize many interventions in Eastern Ukraine are significantly affected by the consequences of the conflict by involving different societal groups and entities. Local communities, civil society groups, IDPs, youth, women and media as target groups are supposed to be involved directly in the intervention activities. However, the connection between state institutions as the target groups and the local population as the final beneficiary is the most significant in comparison to any other relations in the network. State institutions, such as Ministries, are connected during different interventions with local communities, civil society groups, veterans, IDPs, and media to engage in the interventions’ activities. This shows a centralized, rather than localized, approach to addressing local actors and their needs. The local population as a final beneficiary dominates in comparison to the Ukraine population as a final beneficiary. As displayed in , the weight of 78 connections to the local population is significantly higher in comparison to 34 connections to the Ukraine population. However, these connections originate from 11 and 9 different target groups, respectively. At the same time, however, a significant number of interventions in support of the OSCE monitoring of the ceasefire in Ukraine and human rights situation omit references to the population as a final beneficiary and emphasize the OSCE as a final beneficiary.

Given the above network of relations between different actors, there is only limited space for local self-organization of actors. International implementers are supposed to provide target groups with specific means to address the needs. The means as a response to the needs are codified following Hood’s and Margetts (Citation2007) categorization of policy tools. Therefore, the codification distinguishes between 1) the means empowering actors’ capacity to act in view of adversities and 2) and the means enhancing actors’ awareness. Furthermore, the codification of means distinguishes between the resources of regulation, organization, finances and information (based on Hood and Margetts Citation2007; Howlett Citation2004; Natorski Citation2013).Footnote5 Following this categorization, shows that there is a clear tendency to concentrate on three types of means that can potentially can reinforce local self-organization: the capacity to inform, the capacity to organize, and the awareness about relevant information. Based on the means, local actors may be more knowledgeable in relation to the activities to be pursued and have enhanced capacity to organize their activities, even though it seems that the knowledge is to be transferred, rather than locally developed. Different actors are expected to reinforce their different resources to benefit the population as the final beneficiary of these interventions. The empowerment implied in these projects originates, however, from the expertise of implementers from international organizations and transnational NGOs.

5. Conclusion

This paper analyzes complexity features in EU peacebuilding interventions in Ukraine after 2014 to better understand better the implementation of the resilience approach. Given the affinity between the notion of resilience and complexity approaches, the analysis distinguishes between resilience-as-quality of a complex system and resilience-as-thinking about a complex system based on differences between ‘simple’ and ‘general’ complexity thinking. To illustrate this argument, the focus is on the complexity features of non-linearity as well as localization and self-governance in the practices of intervention and the emerging systems of EU peace-building interventions funded by the IcSP.

Following previous academic observations, the scrutiny of this emerging system shows an ambivalent approach to the implementation of resilience. Some element characteristics of the resilience approach, such as incipient non-linearity of the system of interventions, co-exist with policy practices supporting causal linearity and an outside-in approach to local needs addressed by exogenous implementers and central state institutions, rather than by self-organizing local agents. The ambivalence of resilience implementation in the EU peacebuilding interventions can be attributed to the absence of complexity features in the dominant project management practices of EU intervention. The standardized institutional templates of project planning and implementation determine a linear and top-down approach to post-conflict actions. Given this limited presence of resilience-as-thinking in the practices, there is very limited space for enhancing positive feedback loops and drawing from genuine local knowledge and self-organization.

Conversely, the analysis of resilience-as-quality of the entire system emerging from the connections and interdependencies between individual EU interventions suggests some incipient features of complexity. Several elements of non-linearity are embedded in this system of intervention, suggesting equifinality in bringing about post-conflict change and possible positive feedback loops between different elements of individual interventions. However, they appear more as an unintended consequence of the overlap between different interventions than as result of planned design and thinking about resilience in terms of complexity.

The war launched by Russia against Ukraine in February 2022 offers an additional illustration to better understand the contribution of complexity perspective on resilience. The initial phase of this war exemplified that the Ukrainian capacity to resist brutal military invasion also emerged from Ukrainian society’s local self-organization to continue providing basic social services as well as organize territorial defense. Local leaderships of mayors and bottom-up civil society entities reinforced general resilience of Ukraine to combat the Russian army and provided additional means for central authorities to preserve the continuity of state functions (Romanova Citation2022). It also emphasized that the feedback loop of the symbolic continuity of central authorities, headed by President Zelensky, facilitated the functioning of a state system reinforced by local resilience. While it is currently difficult to assess the contribution of external actors’ pre-war interventions to societal resilience, it is a plausible hypothesis that they contributed to Ukraine’s preparedness. For example, numerous projects supporting the integration of IDPs after the occupation of Crimea and Donbass rebellion, reinforced the local capacity to channel the displacement of more than 8 millions Ukrainian citizens (around 20% of country population) in the first two months of war, avoiding major humanitarian catastrophe.

A complexity thinking approach opens several future lines for research regarding the emergence and implementation of the resilience approach in the realm of the EU foreign policy. While this paper focuses on the system of EU intervention in the case of Ukraine, to substantiate further these findings, this insight can be employed in different cases of crisis in which the EU has been significantly involved. The conducted analysis focused on the design of peacebuilding interventions, but future analysis of their implementation can offer additional perspectives on EU practices of field implementation of resilience approach featuring local self-organization. It would be relevant to assess the scope of the adaptation and flexibility of pre-design measures to local conditions and empowerment of local actors in relation to the implementers and donors. Future analyses can potentially include other EU policy instruments employed in response to crises, such as humanitarian aid, technical assistance, and macro-economic aid. Similarly, EU interventions should also be connected to the potential operation of other actors engaged in crisis management and peacebuilding. Nevertheless, the most important avenue for future research is related to the systematic study of practices to take account of multiple ambiguities, dialectical relations and continuous evolution of EU foreign policy. While policy doctrines may provide a sense of institutional identity, they emerge from the frequently disperse, confusing, and contradictory realities of the EU engagement in the world.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ana Juncos, Leonie Holthaus, Frank Gadinger, Heidi Maurer, and Anna Herranz-Surrallés as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Two additional Decisions adopted by the European Commission amended previous decisions by only extending the available budget. Therefore, they were not included in the final dataset.

2 For example, the Commission Decision ‘Support to conflict-affected populations in Ukraine’ (C(2016) 123) included, in fact, support to four different interventions: 1) support to the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission, 2) support for regional media as a way for reconciliation, 3) psychosocial support to promote reintegration and recovery of groups affected by the conflict, and 4) de-mining actions.

3 Two Decisions included two different EAMs, which are the basic form of intervention funded by the IcSP in cases of urgency, crisis and emerging crisis. These measures can be adopted for the period of 18 months and extended twice up to 30 months. In the cases of protracted crisis and conflict, the Commission may adopt a second EAM of a duration of up to 18 months, the Commission adopted Decision that provided continuity to five previously adopted EAMs and also adopted, in 2018, a Decision on Interim Response Programme to continue the support for OSCE Special Monitoring Mission provided since 2014.

4 The visualization of these elements is conducted with the online freeware GraphCommons (https://graphcommons.com) which allows mapping and analyzing of simple networks.

5 Regulatory resources refer to the use of legal acts to regulate activities. Organizational resources refer to bureaucratic and administrative capacities, including equipment and infrastructure. Financial resources mean positive and negative material incentives to steer the behaviour of actors. Finally, information resources involve all sources of knowledge related to reporting, training, advice, research, education, and publications.

References

- Bazilo, G., and G. Bosse. 2017. “Talking Peace at the Edge of War: Local Civil Society Narratives and Reconciliation in Eastern Ukraine.” Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal 3: 91–116. doi:10.18523/kmlpj120118.2017-3.91-116.

- Bourbeau, P. 2018. On Resilience. Genealogy, Logics and World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bousquet, A., and S. Curtis. 2011. “Beyond Models and Metaphors: Complexity Theory, Systems Thinking and International Relations.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 24 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1080/09557571.2011.558054.

- Chandler, D. 2014. Resilience. The Governance of Complexity. London and New York: Routledge.

- Church, C., and M. M. And Rogers. 2006. Designing for Results. Integrating Monitoring and Evaluation in Conflict Transformation Programs. Washington: Search for Common Ground. https://www.sfcg.org/Documents/manualpart1.pdf

- Cilliers, P. 1998. Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems. London: Routledge.

- Council of the European Union. 2013 28 May. Council Conclusions on EU Approach to Resilience. Brussels.

- Council of the European Union. 2015. The EU in a Changing Global Environment - a More Connected, Contested and Complex World . Brussels: 8956/15

- Council of the European Union. 2017. Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit (Brussels, 24 November 2017), 14821/17 . Brussels.

- Council of the European Union. 2020. Council Conclusions on Eastern Partnership Policy beyond 2020. Brussles: 7510/1/20

- De Coning, C. 2016a. “Implications of Complexity for Peacebuilding Policies and Practices.” In Complexity Thinking in Peacebuilding. Practice and Evaluation, edited by E. Brusset, C. de Coning, and B. Hughes, 19–48. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- De Coning, C. 2016b. “From Peacebuilding to Sustaining Peace: Implications of Complexity for Resilience and Sustainability.” Resilience 4 (3): 166–181. doi:10.1080/21693293.2016.1153773.

- Eastern Partnership. 2015. Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit Accessed 21-22 May 2015. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21526/riga-declaration-220515-final.pdf

- European Commission. 2012. EU Approach to Resilience: Learning from Food Security Crises. COM(2012) 586. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2013. Action Plan for Resilience in Crisis Prone Countries 2013-2020. SWD(2013) 227 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2020. Commission Implementing Decision of 28.7.2020 on the Financing of the Annual Action Programme, Part 2, in favour of Ukraine for 2020 to be fnanced under the General Budget of the Union. Brussels, Annex 1. C: (2020) 5161 final.

- European Commission 2021. “Commission Implementing Decision of 13.12.2021.” Multi-annual Indicative Programme (2021-2027) for Ukraine. C(2021) 9351. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/comitology-register/screen/documents/077545/2/consult?lang=en

- European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments. 2018a. Manual of Indicators for the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace – IcSP. Prepared by Karen McHugh. https://ec.europa.eu/fpi/sites/fpi/files/documents/manual_of_indicators_1.pdf

- European Commission. Service for Foreign Policy Instruments. 2018b. FPI Manual on FPI Strategic Plan, project management, monitoring, evaluation and reporting. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/fpi/sites/fpi/files/fpi-manual-july-2018_en.pdf

- European Commission/High Representative. 2013. The EU’s Comprehensive Approach to External Conflict and Crises. Brussels: JOIN(2013)30

- European Commission/High Representative. 2015. Review of the European Neighbourhood Policy. Brussels: JOIN(2015)500

- European Commission/High Representative. 2020. Eastern Partnership Policy beyond 2020. Reinforcing Resilience - an Eastern Partnership that Delivers for All. Brussels: JOIN(2020) 7 final

- European Union. 2014. “Regulation 230/2014 Establishing an Instrument Contributing to Stability and Peace.” Official Journal of the European Union L 77. 1–10 , March 15.

- High Representative/Vice-President. 2016.Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. Brussels.

- Hood, C. C., and H. Z. Margetts. 2007. The Tools of Government in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howlett, M. 2004. “Beyond Good and Evil in Policy Implementation: Instruments Mixes, Implementation Styles, and Second Generation Theories of Policy Instrument Choice.” Policy and Society 23 (2): 1–17. doi:10.1016/S1449-4035(04)70030-2.

- Jackson, P. T., and D. H. Nexon. 1999. “Relations before States: Substance, Process and the Study of World Politics.” European Journal of International Relations 5 (3): 291–332. doi:10.1177/1354066199005003002.

- James, C. 2011. Theory of Change Review. A report commissioned by Comic Relief. http://www.actknowledge.org/resources/documents/James_ToC.pdf

- Jervis, R. 1997. System Effects. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Joseph J and Juncos A E. (2019). Resilience as an Emergent European Project? The EU's Place in the Resilience Turn. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57(5), 995–1011. 10.1111/jcms.12881

- Joseph, J., and A. E. Juncos. 2020. “A Promise Not Fulfilled: The (Non)implementation of the Resilience Turn in EU Peacebuilding.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 287–310. doi:10.1080/13523260.2019.1703082.

- Juncos, A. E. 2017. “Resilience as the New EU Foreign Policy Paradigm: A Pragmatist Turn?” European Security 26 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09662839.2016.1247809.

- Kapsali, M. 2013. “Equifinality in Project Management. Exploring Causal Complexity in Projects.” Systems Reseearch and Behavioral Science 30 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1002/sres.2128.

- Karolewski, I. P., and M. K. Davis Cross. 2017. “The EU’s Power in the Russia-Ukraine Crisis: Enabled or Constrained?” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (1): 137–152. doi:10.1111/jcms.12446.

- Kavalski, E. 2007. “The Fifth Debate and the Emergence of Complex International Relations Theory: Notes on the Application of Complexity Theory to the Study of International Life.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 20 (3): 435–454. doi:10.1080/09557570701574154.

- Knill, C., and J. Tosun. 2012. Public Policy. A New Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Korosteleva, E. A., and T. Flockhart. 2020. “Resilience in EU and International Institutions: Redefining Local Ownership in a New Global Governance Agenda.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 153–175. doi:10.1080/13523260.2020.1723973.

- Korosteleva, E. A. 2020a. “Paradigmatic or Critical? Resilience as a New Turn in EU Governance for the Neighbourhood.” Journal of International Relations and Development 23 (3): 682–700. doi:10.1057/s41268-018-0155-z.

- Korosteleva, E. A. 2020b. “Reclaiming Resilience Back: A Local Turn in EU External Governance.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1080/13523260.2019.1685316.

- Kurki, M. 2011. “Governmentality and EU Democracy Promotion: The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights and the Construction of Democratic Civil Societies.” International Political Sociology 5 (4): 349–366. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00139.x.

- Kurki, M. 2020. International Relations in a Relational Universe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kyselova, T. 2017. “Professional Peacemakers in Ukraine: Mediators and Dialogue Facilitators before and after 2014.” Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal 3: 117–136. doi:10.18523/kmlpj120119.2017-3.117-136.

- Mitchell, M. 2009. Complexity. A Guided Tour. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morçöl, G. 2012. A Complexity Theory for Public Policy. New York and London: Routledge.

- Morillas, P. 2019. Strategy-Making in the EU. From Foreign and Security Policy to External Action. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Natorski, M. 2011. “The European Union Peacebuilding Approach: Governance and Practices of the Instrument for Stability.” In PRIF Report. Vol. 111. Frankfurt am Main: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt.

- Natorski, M. 2013. “Reforms in the Judiciary of Ukraine: Domestic Practices and the EU’s Policy Instruments.” East European Politics 20 (3): 358–375. doi:10.1080/21599165.2013.807805.

- Natorski, M., and K. Pomorska. 2017. “Trust and Decision-making in Times of Crisis: The EU’s Response to the Events in Ukraine.” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1111/jcms.12445.

- Natorski, M. 2020. “United We Stand in Metaphors: The EU Authority and Incomplete Politicization of the Crisis in Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration 42 (5): 733–749. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1792461.

- Paris, R. 2010. “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding.” Review of International Studies 36 (2): 337–365. doi:10.1017/S0260210510000057.

- Petrova, I., and L. Delcour. 2020. “From Principle to Practice? The resilience-local Ownership Nexus in the EU Eastern Partnership Policy.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 336–360. doi:10.1080/13523260.2019.1678280.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002. “Toward A Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Richmond, O. P. 2006. “The Problem of Peace: Understanding the ‘Liberal Peace’.” Conflict, Security and Development 6 (3): 291–314. doi:10.1080/14678800600933480.

- Richmond, O. P. 2010. “Resistance and the Post-liberal Peace.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 38 (3): 665–692. doi:10.1177/0305829810365017.

- Richmond, O. P., A. Björkdahl, and S. Kappler. 2011. “The Emerging EU Peacebuilding Framework: Confirming or Transcending Liberal Peacebuilding?” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 24 (3): 449–469. doi:10.1080/09557571.2011.586331.

- Romanova, T. 2019. “The Concept of ‘Resilience’ in EU External Relations: A Critical Assessment.” European Foreign Affairs Review 24 (3): 349–366. doi:10.54648/EERR2019029.

- Romanova, V. 2022. “Ukraine’s Resilience to Russia’s Military Invasion in the Context of the Decentralisation Reform.” Forum Idei. Warsaw: Stefan Batory Foundation. https://www.batory.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Ukraines-resilience-to-Russias-military-invasion.pdf

- Schatzki, T. R. 1996. Social Practices. A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Stein, D., and C. Valters 2012. “Understanding ‘Theory of Change’ in International Development: A Review of Existing Knowledge.” Paper 1, London: LSE, Justice and Security Research Programme.

- Tocci, N. 2017. Framing the EU Global Strategy. A Stronger Europe in A Fragile World. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tocci, N. 2020. “Resilience and the Role of the European Union in the World.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 176–194. doi:10.1080/13523260.2019.1640342.

- Wagner, W., and R. Anholt. 2016. “Resilience as the EU Global Strategy’s New Leifmotif: Pragmatic, Problematic or Promising?” Contemporary Security Policy 37 (3): 414–430. doi:10.1080/13523260.2016.1228034.

- Youngs, R. 2017. Europe’s Eastern Crisis. The Geopolitics of Asymmetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.