ABSTRACT

The so-called ‘migration crisis’ facing the EU between 2015 and 2017 divided EU Member States and caused a rise in populist and racist discourses. Countries like Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic refused to participate in the EU relocation scheme. This paper explores what enabled this opposition to the EU. It analyses the securitising move of the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS) in constructing migrants as a security threat. It studies the adopted discourse and the effectiveness of the securitisation process, applying the Copenhagen School Approach to securitisation theory. Through an in-depth discourse analysis of a wide range of texts, we argue that the PiS discourse enabled the securitisation of migration and the subsequent decision to refuse the EU relocation scheme.

Introduction

At the height of the ‘migration crisis’Footnote1 in 2015, over one million migrants from the Middle East and North Africa reached the European Union (EU) in a single year. The increase in the number of asylum applications that accompanied this wave of migration into Europe presented a challenge for the EU. It not only tested the EU’s operational and technical capabilities but also the level of solidarity amongst Member States. As Zaun (Citation2018) points out, the lack of effective cooperation and responsibility-sharing not only harmed the Schengen regime and EU trade but also sent out ‘a negative signal about the status of the European integration project’.

Although several Member States were opposed to the EU’s new permanent quota system to relocate refugees (Zaun Citation2018), those most vocal in their opposition were three members of the Visegrad Group (V4); Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, which all refused to accommodate the refugees allocated to them. In response, the European Commission referred them to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in December 2017, and in April 2020, the ECJ ruled that all three Member States had breached their obligations under EU law (Court of Justice of the European Union Citation2020). With the current refugee flow from Ukraine, migration will continue to be a challenge for the EU. Understanding Member States’ responses to migration is therefore important.

The importance of addressing the Member States’ responses to the EU’s migration management plans has been recognised by several scholars. Zaun (Citation2018) discusses the difference between V4 countries and countries such as Germany, Austria and Sweden. Drawing upon Moravcsik’s Liberal Intergovernmentalism, Zaun highlights national electoral pressures in relation to Member States’ responses to migration. Barlai et al. (Citation2017) address the perspectives on the ‘migration crisis’ of eighteen countries, including Poland and Hungary. For Hungary, Barlai and Sik (Citation2017, 152), indicate how the Government endeavoured to generate a ‘moral panic’, despite public opinion on migration already reflecting xenophobia. Bocskor (Citation2018), and Szalai and Gőbl (Citation2015), also address the securitisation of migration in Hungary, focussing on discourse and practice respectively. Both emphasise the construction of immigration as a national security issue and a cultural and economic threat. Vezovnik (Citation2018) analyses the media’s securitising discourse on refugees in Slovenia and confers the representation of refugees as criminals and a health risk. The securitisation of migration has also been studied on the EU level. Interestingly, while Huysmans (Citation2000), Karamanidou (Citation2015), Vaughan-Williams (Citation2015) and Horii (Citation2016) notice signs of the EU’s securitisation of migration before 9/11, Léonard and Kaunert (Citation2019) claim that asylum seekers have not been presented as a threat to the EU before the ‘migration crisis’. Léonard and Kaunert (Citation2019) also discuss the UK and Spain, with Spain refraining from securitising migration on both national and EU level, while the UK associating migration to terrorism on the domestic level but not in the EU.

Uncovering constructions of migration in Member States’ discourse can enable the desecuritisation of migration which in turn can inform EU coordination in migration management. While securitising discourse adopted in Hungary was studied by various scholars (Szalai and Gőbl Citation2015; Barlai and Sik Citation2017; Bocskor Citation2018), there is little research on Poland. Nevertheless, Poland led the V4 in 2016–2017, following the height of the 2015 ‘migration crisis’. It also has a long history of emigration, a pro-European attitude (see below), has had a considerably small population of immigrants (The Office for Foreigners Citation2020) – at least prior to millions of refugees entering Poland fleeing the Russian invasion in Ukraine, and faces labour shortages (Polskie Radio24.pl Citation2018). In addition, contrary to Hungary, Poland was not directly affected by the ‘migrant crisis’. While Sadowski and Szczawińska (Citation2017) in Barlai et al. (Citation2017) discuss the migration context of Poland, their consideration of political discourse is limited. This article uses securitisation as a theoretical framework and, following Lijphart’s typology of case studies (Citation1971), presents Poland as an interpretative case study. As such, the case study analysis does not aim to offer generalisations but instead focuses on Poland specifically in order to enhance the understanding of its refusal to help refugees in 2015 and its opposition to the EU relocation scheme. The article contributes to the literature by analysing the discourse of the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS),Footnote2 on the ‘migration crisis’. It also considers the audience’s acceptance of the securitising move. The article first discusses the Copenhagen School’s approach to securitisation, which serves as the framework of analysis, and the method of discourse analysis. The second section applies discourse analysis to understand how PiS framed the ‘migration crisis’ and presented immigrants as a threat to Polish society, thereby securitising the ‘migrant other’. The final section reflects on the securitising move in terms of audience acceptance.

The securitisation framework: the Copenhagen school and discourse analysis

The securitisation of migration is not a new phenomenon. It gained significant academic attention after 9/11, but the ‘migration crisis’ has boosted interest in the matter (see for example Lazaridis and Wadia Citation2015; Squire Citation2015; Vezovnik Citation2018; Léonard and Kaunert Citation2020). Whereas there are different variants of securitisation theory (Balzacq Citation2010a), we apply the most prominent approach (according to for example Hansen Citation2012; Sperling and Webber Citation2019), developed by the Copenhagen School (CS), which originally coined the term ‘securitisation’. This ‘philosophical’ or ‘linguistic’ approach, as it used to be categorised, draws on Austin’s speech act theory, and assumes the performativity of utterance. It defines securitisation as a process where, through a speech act, the securitising actor labels something as an existential threat to the referent object and argues for the use of extraordinary measures to counter the threat (Wæver Citation2000). This securitising move is successful when the presented problem is accepted as a security issue by a relevant audience. According to the CS, securitisation is an intersubjective process (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998), implying there are no security issues in themselves, and anything can become a security issue when labelled as such (when fulfilling conditions). Importantly, the securitising actor does not have to be a state (although this is considered the ideal case) but it must have authority and power (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998).

Securitisation theory, while growing in popularity, has also faced criticism. This has included its focus on discourse which may lead to the omission of securitisation taking place through practices (Balzacq Citation2008), its applicability beyond Western countries (Wilkinson Citation2007; Barthwal-Datta Citation2009), the need for adjustments when applied to the EU (Neal Citation2009; Baker-Beall Citation2010) and questions about the role of the audience (Balzacq Citation2005). In fact, various questions have been asked about the audience acceptance in the literature, such as ‘which audience is when and why most relevant?’ (Stritzel Citation2007b, p. 363), ‘[h]ow does the power of the audience relate to the decisionism of the speech act event?’ (Stritzel Citation2007b, p. 363), and ‘what exactly constitutes audience acceptance?’ (Balzacq, Léonard, and Ruzicka Citation2016, 449). Balzacq (Citation2010a) distinguishes two types of audience support: formal and moral. While formal support is essential and provides a mandate to adopt a policy, the lack of moral support can undermine the success of the securitising move. Balzacq (Citation2008) also notes that securitisation can take place even without the consent of an identifiable audience.

In this article, the relevant audience is understood as Polish citizens who can grant both moral and formal support through the elections. As suggested by Balzacq (Citation2010b), the acceptance by the audience should not only be based on polls, and this article measures acceptance in three ways. First, it considers the success of the securitising actor (PiS) in the 2015 parliamentary elections when PiS’ campaign focused heavily on the ‘migration crisis’. Second, it analyses the Poles’ attitude towards refugees based on data from the Public Opinion Research Center (CBOS),Footnote3 and third, it considers civil society support for or opposition to government actions. The securitising actor is here PiS, which had authority and power being one of the two main parties in Poland which won the elections and formed a government, with a majority of ministers, the prime minister and the president allocated to PiS. The referent object is identified as Polish societal security, health security and national security (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998). Finally, the extraordinary measure is the opposition to the EU relocation scheme. While Poland did not reintroduce border controls at the EU’s internal borders,Footnote4 it introduced other measures such as strengthening external border controls, extensions of the detention time at the border, and changes in counter-terrorism legislation.Footnote5 However, these measures have contributed to the securitising discourse and are therefore not considered as extraordinary measures requiring legitimisation.

This article applies discourse analysis, the most commonly used method in securitisation studies (Balzacq Citation2010b). Whereas there are multiple variations of discourse analysis (Shepherd Citation2008), discourse is understood here as an ‘institutionalized way of talking (…) that regulates and reinforces action and thereby exerts power’ (Link cited in Jäger and Maier Citation2009, 35). The method used involves a three-step process – preceding the analysis presented in this article – that draws on the technique of Baker-Beall (Citation2010). The first step involved the selection of texts. The authors identified 23 texts (see annexe A) from the period between 2015 and 2019, which present the discourse of PiS. Importantly, the understanding of ‘text’ is broad, including oral speeches (transcribed), existing transcripts of speeches, media interviews (videos and texts), media summaries of interviews, twitter posts and campaign adverts (videos). This allowed for greater representativeness in the sample, avoiding over-reliance on a specific politician or type of text. The text selection was based only on their focus on either immigrants, the ‘migration crisis’, or migration management, not on a search for securitising discourse. All selected texts have been transcribed and translated. The second step was what Baker-Beall (Citation2010, 65) calls mapping the discourse, where a direct examination of these texts leads to the identification of key words, assumptions, terms and phrases, which are then categorised into themes. All texts have been analysed independently by both authors to distinguish the most dominant themes. The search was concluded when including more texts did not result in the identification of new themes. The third step focussed on intertextuality and the interrelations across different texts, more specifically the patterns and connections between themes identified within those texts.

The discourse on the ‘migration crisis’ in Poland

This section analyses the identified themes from the three-step process discussed above. Upon mapping PiS’ discourse on the ‘migration crisis’, the following five dominant themes were identified by both authors: ‘Security’, ‘Muslim other’, ‘We want to help, but … ’, ‘The EU has gone astray’, and ‘Our other’. The analysis and author discussions concluded that limiting the focus to discourse on migrants would be inadequate. PiS not only securitised migrants by framing them as a threat, but its rhetoric on help, Muslims, security and the EU also contributed to the securitisation of migration. PiS furthermore not only presented immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa as a threat but also compared them to immigrants from eastern Europe, which further strengthened the portrayal of the Muslim as a dangerous other. An additional theme was identified in the PiS’ discourse: the response of the opposition party to the ‘migration crisis’. This theme was however excluded from the analysis as it does not add new material and focuses on discrediting the opposition for their initial declaration to accept refugees while repeating other identified themes.

1. ‘Security’

This first theme demonstrates how migration was presented as a threat to health security, a terrorist threat, and a threat to societal security. In the statements analysed, PiS politicians commonly referred to migration as a security threat, directly or indirectly. PiS has stated that providing security is a priority for the Party. As early as September 2015, PiS Chairman Jarosław Kaczyński, linked migration management to security by presenting people arriving in the EU as criminals:

It is a serious danger that a process will start which, in a nutshell, will look something like this: first the number of foreigners increases rapidly, then they do not obey, (…) they declare that they will not obey our laws, our customs. And later, or simultaneously, they impose their sensitivity and their requirements in public space, in various areas of life, and in a very aggressive and violent way (Text 3 2015).

This example demonstrates that the narrative constructing migrants as a security threat, was established before the Paris terrorist attacks (December 2015) and subsequent attacks in Europe. This narrative of migration as a threat to security was articulated in different ways, with migrants constructed as a threat to health security, a potential terrorist threat, and a threat to societal security.

Regarding the construction of migrants as a threat to health, Kaczyński referred to cases of diseases amongst asylum seekers to create an atmosphere of fear:

And threats exist. There are already symptoms of very dangerous diseases that have not been seen in Europe for a long time: cholera on the Greek islands, the dysentery in Vienna. There are some talks about other, even more serious diseases. Well, there are also some differences related to geography, various types of parasites, protozoa, which are often in the bodies of these people, they can be dangerous here. (…). (Text 5 2015).

Similarly, several statements mentioned the terrorist threat. For PiS, accepting refugees and asylum seekers meant inviting terrorists into Poland. The threat of terrorist attacks like those seen in Paris or Brussels were articulated as a reason for refusing asylum seekers under the relocation scheme. This explanation was given in Parliament by Deputy Minister Jakub Skiba:

Firstly, the implementation of this relocation decision cannot take place if Poland would be exposed to any danger. In the face of a situation in which terrorist acts become a certain norm, Poland can’t allow such a threat to appear on our territory (Text 9 2015).

Minister of Internal Affairs Mariusz Błaszczak argued that terrorists are among the migrants coming to Europe, which would justify closing the borders to provide security:

(…) as part of this migration of people from 2015 also terrorists took the route through the Balkans and they later participated in the terrorist attacks in France. There is no doubt because it is a fact that we have a state of emergency in France. And my job, as the Minister of Internal Affairs and Administration, is to ensure security in Poland by sealing procedures, making borders safe. (Text 10 2017).

Interestingly, although relocating immigrants has been explicitly connected to terrorism, Minister of Foreign Affairs Waszczykowski admitted that Poland is not particularly at risk of terrorist attacks (Text 11 2017). Furthermore, even though the terrorist threat was repeatedly invoked by PiS, it was not central to its securitising narrative. The real threat was presented as uncontrolled migration, predominantly of Muslims, who may not all be terrorists but will disrespect Polish law and culture. PiS frequently used the numbers of asylum seekers to be relocated to Poland to convince the Polish people that the wave of Muslim immigrants poses a threat to Polish society. Kaczyński stated the following:

I will remind you that Finland has accepted 100 [refugees], today it has 26,000, a conversion rate of 1: 260. For us, a much smaller conversion would be enough to create a big problem related firstly to security, and this is not just about terrorism, I am talking about ordinary everyday safety. There is no reason for us to radically lower the quality of our lives. (Text 18 2017).

PiS presented migrants as difficult to control, as angry men who fight with each other and with the security services. In 2017, Minister of Internal Affairs Błaszczak stated:

(…) if there was a crisis, such as in Hungary in 2015, when clashes between the refugees (…) and the Hungarian police (…) took place on the Serbian-Hungarian border. Well, the point is to be prepared for such a situation in a way of having places where those who broke the law would wait for deportation (Text 12 2017).

The ‘security’ theme represents a crucial element of the PiS discourse. By constructing migration as inseparable from security, PiS achieved three effects. First, it securitised irregular migration by presenting it as a significant danger to national security (the terrorist threat), societal security and health security. Second, PiS’ rhetoric helped justify the decision to oppose the EU by revoking fundamental Polish values, and by presenting PiS as a defender of the nation. Third, constructing migration as a security issue allowed PiS to present the EU as lost and irresponsible, which further legitimised their rejection of the EU relocation scheme. These themes are further discussed below.

2. ‘Muslim other’

As discussed, PiS has represented migrants as a threat to national, health, and societal security, particularly targeting male Muslim immigrants. On many occasions, PiS has claimed that they are not refugees but economic immigrants. PiS has presented them as people who exploit the conflict in the Middle East and the ‘real’ victims of conflict, and cause chaos on the borders to enter the EU. For the Party Chairman Kaczyński, they represent the opposite of the Polish emigrants who work hard and with humility (Text 3 2015). This section presents two representations of Muslim immigrants in PiS’ rhetoric: capable terrorists and uneducated barbarians.

The terrorist depiction of Muslim immigrants gained traction because of two arguments: first, ISIS fighters have claimed to reach the EU through migration routes and second, PiS, has labelled radical Islam to be a religion of war. According to MP Stanisław Pięta:

[…] Islam is not a religion of peace, but a totalitarian society management system. There isn’t the slightest possibility of working out a peaceful agreement. The Islamists came here to kill Europeans and subordinate those who they will not be able to kill (Text 16 2017).

This terrorist threat posed by Muslims was, according to Pięta, strikingly neglected by left-wing governments of Western European countries.

We must show the disgusting, hideous political alliance between the leftist political circles of Western Europe and the groups of Muslims. We must remember that Muslims who have already acquired electoral rights, actively participate in political life and vote for left-wing groups. Let’s remember that in the last presidential election in France, the candidate of the left, Macron was supported by all Islamic groups and associations in France. The Left feeds on the support of Islamists and allows for terrorist organizations to function (…) (Text 16 2017).

He further claimed that Muslims support terrorism and cannot be integrated into European societies:

Let’s remember that in the classes attended by Islamic youth there were explosions of enthusiasm and joy after the attacks in Brussels or Paris. (…) The leaders of European countries should realize that any integration of radical Islam is impossible. Muslims living in Europe despise Europeans, reject liberal value systems and are more and more confrontational (Text 16 2017).

PiS Politicians have also aimed to dehumanise Muslims by presenting them as uncivilized. An especially vulgar description of the Muslim world was presented by Waldemar Bonkowski, Senator from PiS:

(…), it seems that it was Ms Pomaska or someone else has said that they [immigrants] should come to Poland and we should, as she said, enrich ourselves culturally. I would propose that Sejm [the Lower House] should organise a trip for the totalitarian opposition to Egypt, to Cairo, or to Luxor, and if they do not want, to the Holy Land. And it is enough if they go to Eilat and cross the border with Aqaba … It is literally … I do not want to offend Polish piggery, … as if from the living room they entered the pigsty. No! Because a Polish pigsty is clean, it is tidy. If you think that these people are able to enrich us culturally, I feel sorry for you, (…) These people cannot be civilized. They cannot even be integrated, because their religion does not allow them to integrate with us. (Text 20 2017).

This narrative claimed that even if initial numbers of refugees would be small, they would rapidly increase as many immigrants have large families. In a 2015 political advert, immigrants were presented as predominantly adult Arabic men that form an enormous, uncontrolled mass of people. The video shows a temporary camp that is neglected, indicating that they do not care about their environment (Text 4 2015). Another PiS political advert from 2018 shows what Poland could look like in 2020 if it would take refugees. It shows long queues of Arabic men watched by police (suggested) wearing face covering (Text 22, 2018). It also shows immigrants who try to run away and fight, resulting in chaos on the streets: riots, fires, people killing each other. The narrator talks about everyday sexual attacks, attacks of aggression and residents living in fear (Text 22 2018).

PiS Chairman Kaczyński has also mentioned the Muslim attitude towards gender equality, pointing out a paradox in European values: on one hand, Western countries support this equality, even homosexual relations (which according to Kaczyński should be tolerated but not supported) and on the other hand, they invite cultures to Europe that disrespect gender equality (Text 23 2019).

In short, PiS adopted securitising discourse that constructed Muslim immigrants as a danger to national security, due to the terrorist threat, and to Polish identity and culture. These two constructions allowed PiS to present immigrants as criminals that should not receive help and should not have been considered asylum seekers in the first place. Simultaneously, PiS sought to present itself as a humanitarian actor willing to help those who need it and are not considered a threat.

3. ”We want to help, but … ”

PiS entered the debate about the relocation of refugees with a very strong ‘no’ to any number and category of refugees. However, after winning the elections, there was a shift from ‘we won’t take any refugees’ to ‘we want to help, but … ’. PiS could not completely say ‘no’ to refugees and therefore presented itself as willing to help despite refusing to implement EU decisions. PiS declared a willingness to help refugees on several occasions. Already in autumn 2015, Prime Minister Beata Szydło reportedly had stated that Poland cannot ignore the problem, ‘which is a problem of the whole of Europe. [Poland] cannot turn [its] back on people who save lives by escaping death’ (Text 1 2015).

The PiS rhetoric emphasises its willingness to help and offers several reasons to object to the EU relocation scheme. The seven most common justifications to oppose the scheme are discussed here. First, the main ‘but’ was always security. PiS repeatedly stated that it would not compromise the security of Poles. Polish authorities argued that security could only be guaranteed if immigrants’ identities were verified, which they claimed was impossible due to fake or contradicting documents, as emphasized by Deputy Minister for Internal Affairs Skiba (Text 9 2016). Secondly, immigrants were presented as exploiting conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa, to relocate to Europe and improve their quality of life. The Polish Government repeatedly stated that Poland cannot be forced to relocate what they consider economic migrants, as the competences in this area lie with the Member States (Text 2 2015).

Third, PiS has frequently claimed that the ‘migration crisis’ is a German problem. As PiS MP Lichocka said, Poland could not accept economic migrants that try to reach Germany:

And they want to go to Germany. Even those who stay for a moment in other countries where they are admitted (…). Well, this is Eldorado for them. We have to remember that it is primarily a German problem (Text 1 2015).

And who created this magnet, this big, huge magnet that attracts economic migrants? Germany. And it is their problem. Orban was right about it. It is their problem, not ours. We can help, but I will repeat: only in a way that will be safe for Poles (Text 3 2015).

Fourthly, as stated by PiS Chairman Kaczyński, there were also ‘moral-historical’ objections to the relocation scheme:

There are also different arguments of moral or moral-historical nature. The first of them is colonialism. For the life of me, Poland didn’t take part in it. The second argument refers to the policies of some European countries and of the United States in the Middle East in recent years (…). Poland did not participate in this either (Text 3 2015).

This argument, however, is somewhat surprising given that Poland was part of the ‘Coalition of the willing’ for the 2003 Iraq invasion and sent troops to Afghanistan (2002–2021).

The fifth ‘but’ focuses on the ‘desirable’ group of immigrants. As Deputy Minister of Interior and Administration Skiba said, Polish migration policy prioritizes help to the most vulnerable group (Text 9 2016), including women, children, the elderly, and minorities (in this case the Christians). Prioritising Christians was justified in two ways. First, as Skiba stated, Christians are among those most persecuted in the Middle East (Text 9 2016). PiS tried to present itself as wanting to help the ‘real victims’, as opposed to economic immigrants in search of social benefits, who will threaten European culture. The second justification for prioritising Christians concerned integration within Polish society. According to Skiba, given the Polish attachment to Christianity, sharing the same beliefs would guarantee better integration (Text 9 2016).

Further, PiS’ idea of help was based on humanitarian aid, not on accepting refugees in Europe. PiS emphasized repeatedly that Poland will take responsibility by offering financial help, but without media hype and political fireworks (Text 11 2017). Regarding those who had already arrived, Minister of National Defence Błaszczak said that Europe should follow Australia’s example; providing shelter, food and water, and send them back to the place where they came from (Text 13 2017).

The last ‘but’ involves PiS’ argument that refugees did not want to come to Poland in the first place. Therefore, the Government had to oppose any mechanism that would relocate refugees to Poland by force, as according to Minister of Foreign Affairs Waszczykowski, this would mean forced resettlement (Text 11 2017).

The rhetoric ‘We want to help, but … ’ allowed PiS to present itself as willing to support the ‘real’ victims without undermining Polish national and societal security, something – according to PiS – the EU was unable to do. The critique on the EU’s response to the ‘migration crisis’ is another distinguishable theme in the PiS narrative, which we turn to next.

4. ‘The EU has gone astray’

PiS’ rhetoric on refugees continuously emphasised the mistakes on the part of the EU. Although Poland has been a largely euro-enthusiastic country (according to Eurobarometer, above the average in terms of trust in the EU between 2005 and 2020; see Annex B), during the ‘migration crisis’, the Government openly and directly criticized EU decisions. It argued that the EU was to blame for Poland’s unwillingness to relocate refugees, as it did not provide a safe way to do so. The Government spokesperson, Rafał Bochenek, said:

(…) the mechanism promised by the European Union for verification of people who were coming from the Middle East, doesn’t work at all. It turned out that those people that have been assigned to us, had several passports. We couldn’t verify their real names, their family connections. It shows that the system, which we have talked about from the very beginning, the relocation system that is proposed by the EU institutions, is firstly ineffective and secondly does not guarantee the security of citizens of the Member States (Text 14 2017).

PiS found multiple faults in the EU’s ability to manage the ‘migration crisis’, like failure to close the external borders, risking the security of European citizens and not confirming the immigrants’ identities. It also claimed that the relocation scheme in fact worsened the situation, as immigrants – now convinced they will be allowed to enter the EU – risked their lives during the journey. PiS has furthermore stated that the scheme has strengthened smugglers’ networks, and that it breaks EU law, as it is the Member States’ competence to decide on accepting economic migrants. Minister of Internal Affairs Błaszczak, also accused the EU of funding NGOs that help economic immigrants apply for asylum:

some of the NGOs, financed by the European Union, organise trainings for economic emigrants from Asia, to show them how to effectively apply for international protection, i.e. how to deceive Polish border guards (Text 10 2017).

Generally, the EU is presented as lost and in need of guidance due to blind political correctness and its neglect of Christian values. PiS MP Pięta stated:

Western Europe lost its identity fighting against Christianity. The European left destroyed the spirit of community. Social egoism, which is the leading idea of the liberal-left states of the Old Continent, turns out to be deadly for Western communities. It turns out that Western European societies have lost their instinct for self-defence, and despite the deaths of hundreds of innocent people, they still intend to plunge into the absurdities of false tolerance and political correctness (Text 16 2017).

PiS blamed the European left-wing parties and accused Macron of supporting Islamist groups (Text 16 2017). It urged the EU to ‘wake up’ and realize that their idea of a united Europe has failed. According to Prime Minister Szydło, the EU had to take immediate action to provide security and to stop more people from dying (Text 15 2017). He suggested for Europe to follow Poland, which prioritises security and strengthens the army. This critique, however, did not imply that PiS no longer supported Polish EU membership, as pointed out by Prime Minister, Szydło:

We do welcome all the benefits related to membership of the European Union. Therefore, we shall strive to increase the effectiveness of EU efforts. To ensure full compliance with the European acquis and the principles that underlie the process of European unification (Text 7 2015).

This led to a presentation of PiS as the leader and defender of the EU based on the ‘right’ values. This narrative may seem surprising, given that the European Commission has taken Poland to the ECJ on several occasions, but according to PiS, this gave Poland a stronger voice in the EU. As seen in Waszczykowski’s evaluation:

After twelve months, we can confidently say that Poland has become more secure. (…) In the Union itself, in the debate about the future of the European project, our voice is heard, and our arguments are considered. We could have seen this during the last visit of Chancellor Angela Merkel in Warsaw (…). Instead of standing on the side and cheering for the main players – we ourselves entered the game on the international arena. It turned out that we can develop tactics, present arguments, and convince people of them. We can withstand the first wave of reluctance, attacks and even assaults. We can build coalitions and win. This was the case for (…) the presence of NATO troops in Poland and the migration problem (Text 11 2017).

In fact, PiS considered the Polish response to the ‘migration crisis’ and their refusal to relocate refugees as one of their main achievements. According to PiS, they have saved Europe from continuing this mistaken policy. As Prime Minister Szydło argued, the EU should follow Poland and reject political correctness:

Because being in the European Union does not mean agreeing on political correctness, but it means taking responsibility also when the political elite in Brussels cannot do it, blinded by political correctness, scared and letting others take the wind out of the sails. (…) we must take care of security, because it is fundamental (Text 15 2017).

To convince voters that the Polish Government was not alone in their position regarding the ‘migration crisis’, PiS posted statistics presenting the disapproval of the EU’s response on Twitter, under the title ‘Do not let yourself be told that aversion to refugees is something bad. Poles are no exception in Europe. Pass it on!’. And below it: ‘Most Europeans disagree with Brussels’ immigration policy’ (Text 17 2017).

Further, PiS Chairman Kaczyński, responding to claims that Poland, as one of the biggest recipients of the European funding, should show more solidarity, argued that Poland does not owe the EU anything. He makes the point that the pre-accession funding was modest, and the Polish economy was exploited by the EU:

Poland opened its market 12 years before joining the European Union. Well, there were pre-accession measures [funding], but they were quite modest, and they came much, much later. The cheap Polish labour force, still cheap today, also serves those economies. When it comes to using European funds, companies from those countries benefit to a large extent. (…) Well, tens of billions of zlotys are transferred to the West every year from Polish enterprises, (…) tax-free. (…) And that is why I repeat, nobody will impose on us – because we receive funds – a situation in which we will have to decide on [how to deal with] a social catastrophe (Text 18 2017)

In addition to this, he also referred to World War II and Poland being excluded from the Marshall Plan. The cost of these events, according to Kaczyński, was further proof that Poland not only deserved the received EU funding but also could not be obliged to relocate refugees because of it (Text 18 2017).

This theme shows how PiS opposed the EU while trying to preserve the pro-European rhetoric to avoid losing voters. It framed this narrative by presenting an ‘EU in crisis’, in need of help and guidance from Poland because of left-wing and non-Christian influences. The rhetoric on the EU not only contributed to the construction of Poland as a victim of the past that became strong and independent without help from the EU but also implicitly securitised migration as the primary threat that the EU is unwilling to see. It sought to convince Polish society that the EU’s way of managing the crisis is incorrect and that Poland does not have the legal or moral obligation to accept this response. In short, references to the EU were used to legitimise the extraordinary measure to refuse refugees and to achieve public acceptance for this decision.

5. ‘Our other’

The last theme identified is the construction of ‘our’ other. In contrast to the aggressive, violent, difficult to control ‘Muslim other’, PiS presented a ‘desirable’ other. This represented immigrants that were welcome in Poland as they ‘fit’ Polish society and – with a similar culture – could more easily be integrated. Therefore, not posing a threat to Polish identity, they were labelled as ‘our’ other. In this group included refugees that were Christian, female, children, and elderly people, as well as immigrants from Eastern Europe.

The Polish Government defended its decision regarding the relocation scheme by stating that Poland was already taking refugees and economic migrants from Ukraine. This served as an additional justification of non-compliance with EU policy. Below are two statements made by Minister Waszczykowski:

A separate issue is the perception of Poland’s contribution to the management of migratory pressure from the East by some Western European politicians. More than one million people, mainly citizens affected by war and the economic crisis in Ukraine, live and work in our country. This enormous number shows that the Polish policy in this field is effective, however, we achieve our goals in different ways (Text 11 2017).

Poland is the host country of immigrants. I will remind you that last year Poland issued 1,267,000 visas only to Ukrainians, and this year, in the first six months, we issued another 750,000 visas, and a large number of visas were issued to Belarusians and other Eastern societies. Therefore, Poland is open to visits but also to migration because many of these visas were supplemented with the right to take up employment (Text 19 2017).

PiS presented Ukrainian immigrants as people who do not cause problems, could easily be integrated within the society. This was directly contrasted with Muslim immigrants who were presented as violent men posing a threat to Polish women and children, unable to integrate into Polish society, as claimed by Minister Błaszczak:

We have no problems when it comes to integration with people who come to Poland and are citizens of Ukraine, many of them are looking for Polish roots. Integration is a problem in the West of Europe in relation to those who for years have not assimilated to European society, more – who impose their own sensitivity, their own rights on the hosts … (Text 12 2017).

Immigrants from Eastern Europe, especially Ukraine, were not only portrayed as welcome in Poland but this construction was also accompanied by changes in the law that were to facilitate their influx to help resolve demographic challenges and labour shortages. This indicates the importance of identity, religion and culture for PiS, emphasising the narrative that not all immigrants pose a threat; mainly Muslims do.

The securitising move and the audience’s response

The PiS speech act not only directly securitised immigrants invoking national, societal, and health security, but also with rhetoric on help, the EU, and immigrants from Eastern Europe. Following Balzacq (Citation2010b), to determine whether this securitising move can be considered successful, we not only analyse the public opinion on migration before and during the ‘migration crisis’, but we also consider that the securitising actor (PiS) won the 2015 parliamentary elections, and the lack of significant civil society opposition to subsequent government actions.

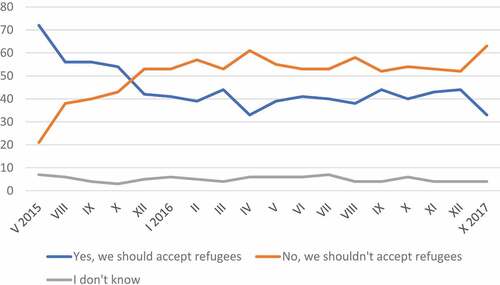

Noteworthy, since 2004 a majority of Poles have been generally supportive of helping refugees when the country of origin was not explicitly stated. In 2004, 48% of Poles supported the refugees’ right to settle in Poland and 27% the right to stay until they can return to their countries (75% overall) (CBOS Citation2015b). In 2015, these views were held by respectively 54% and 22% (76% overall) (CBOS Citation2015b). During the ‘migration crisis’, some changes in the numbers can be observed (see chart no. 1). While in 2015, 72% of the respondents agreed that Poland should accept refugees from countries affected by armed conflicts, at the end of 2017 this was only 33% (CBOS Citation2018).

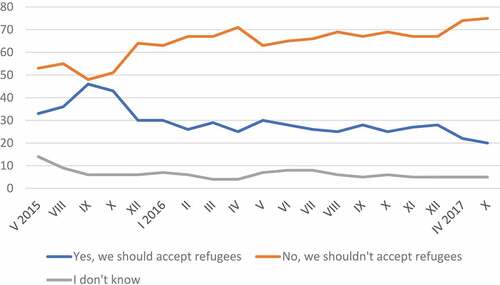

In addition, already in 2004, when respondents were asked whether the presence of foreigners is beneficial or detrimental, the results presented significantly less favourable attitudes towards certain groups, especially Arabs. By May 2015, 63% of respondents considered the presence of Arabs in Poland as detrimental (CBOS Citation2015a, 2). Before the ‘migration crisis’, in May 2015, only 33% agreed Poland should accept refugees from the Middle East and Africa (see chart no. 2), and at the end of 2017, this had dropped to 22% (CBOS Citation2018). At the same time, in May 2015, 53% of respondents were against accepting refugees and this number increased to 75% in October 2017 (CBOS Citation2018).

These numbers indicate two important conclusions. First, they show a strong negative attitude towards Arab refugees already before the summer of 2015. presented a significant drop from 72% of respondents supporting refugees in general to 33% for refugees from the Middle East and Africa. Even though both numbers decreased significantly in 2017, it shows that already before PiS’ securitising speech act, irregular immigrants from the Middle East and Africa were less welcome.

Chart 1. Attitude towards refugees (without stating their country of origin).

Chart 2. Attitude towards refugees from the Middle East and Africa.

Second, both present a significant change throughout the ‘migration crisis’. While chart 1 shows the significant drop before the electoral campaign and the discussion about the ‘migration crisis’ (August/September 2015), shows an increase of support for accepting refugees during the spring and summer of 2015. Nevertheless, it dropped significantly at the time of the elections and this trend continued throughout the ‘migration crisis’ (until the end of 2017) in both cases.

Although it is difficult to determine whether this decrease of willingness to accept refugees was a direct effect of the PiS’ securitising speech, three indicators suggest a successful securitising move. First, the time frame of this decline coincides with the time of the securitising move. Second, PiS won the parliamentary elections (with the highest number of votes – 37,58%, and 235 seats) with a campaign that was primarily focused on managing the ‘migration crisis’. Third, Poland did not relocate refugees, and this decision did not cause significant opposition from Polish society.Footnote6

Conclusion

This article discussed the Polish ruling party’s discourse on the ‘migration crisis’ from 2015 to 2017, which enabled its opposition to the EU relocation scheme. While the PiS securitising discourse on the ‘migration crisis’ was not unexpected, the analysis demonstrates that in addition to the discourse on migrants and refugees, factors such as the rhetoric on the EU and immigration from Eastern Europe also played a role in PiS’ securitising speech act. The approach identified five different themes: ‘Security’, ‘Muslim other’, ‘We want to help, but … ’, ‘The EU has gone astray’ and ‘Our other’.

PiS entered the electoral campaign with discourse that was to securitise immigration and legitimise the opposition to EU decisions on the relocation of migrants. This discourse was further sustained throughout the time of the ‘migration crisis’ and when Poland was taken to the ECJ. The fact that Polish society was prejudiced against immigrants from the Middle East and Africa but is at the same time also largely pro-EU is important in explaining PiS’ rhetoric. The Party capitalised on the already less welcoming Polish attitude towards Arab refugees by presenting all asylum seekers as Muslims, and constructed them as a threat to national, societal, and health security. Understanding the Polish attitude to ‘our other’ and the ‘Muslim other’ requires further research, especially considering recent events on the borders with Belarus and Ukraine.

PiS also needed to include the EU in its discourse, given the generally pro-EU Polish attitude. While the EU as such could not be securitised, sympathy towards left-wing parties and values, multiculturalism and tolerance was used to demonstrate the EU had lost its way. The rhetoric of financial support to humanitarian aid and of welcoming immigrants from Eastern Europe helped PiS to construct itself as a party in solidarity with those fleeing war, while still protecting Polish citizens.

The presented themes not only contributed to the construction of the ‘Muslim other’ as a threat but also to the representation of Poland as a strong and independent European country that will take the lead in the EU and help those in actual need. Even though Polish society, according to the data from CBOS, displayed anti-Muslim sentiment prior to the ‘migration crisis’ and the adoption of the securitising discourse, a further decline in accepting migrants from the Middle East and Africa can be observed. Moreover, while Poles generally supported the acceptance of refugees (when their origins were unknown), this drastically changed during the analysed time period. In combination with the electoral result, this shows that there is no indication, such as significant opposition from civil society, that the audience did not accept the extraordinary measure, i.e. the opposition to the EU relocation scheme.

This analysis raises questions for the wider region. Although methodological differences prevent a direct comparison of discourses in Poland and Hungary (Szalai and Gőbl Citation2015; Barlai and Sik Citation2017; Bocskor Citation2018), two remarks can be made. First, both Poland and Hungary constructed migrants as a threat to national and societal security, which as seen in Barlai et al. (Citation2017) may be common for many European countries. Second, while the Hungarian discourse mentions the threat to the labour market (Szalai and Gőbl Citation2015; Barlai and Sik Citation2017; Bocskor Citation2018), this argument is absent in the Polish context, due to existing labour shortages. Still, PiS’ rhetoric favoured immigrants from eastern Europe which can fuel the othering of Muslims. Also, the Hungarian discourse analysed by Szalai and Gőbl (Citation2015), Barlai and Sik (Citation2017) and Bocskor (Citation2018) did not give particular importance to the EU, which would be interesting to further explore to enhance our understanding of EU-Member States relations in the region.

The adopted discourse not only securitised migration but also convinced Poles that Poland can oppose the EU. This raises the question whether the aim of the Party was the securitisation of migration in itself or the legitimisation of opposition to the EU. Further research – studying other Member States’ political rhetoric and other areas of securitisation – can help us better understand how securitising language can help oppose (or perhaps support) EU decisions, and influence relationships and power dynamics within the EU.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge dr Christopher Baker-Beall for his support for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. This article refers to ‘immigrants’ and ‘migration crisis’ rather than to ‘refugees’ or ‘asylum seekers’ and ‘refugee crisis’ to reflect the discourse in Poland, in particular the language used by the Law and Justice Party.

2. The Government formed in 2015 was a coalition of the Law and Justice Party – Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) (with majority), Poland Together – Polska Razem (PR) and United Poland – Solidarna Polska (SP).

3. In Polish, Centrum Badania Opinii Spolecznej.

4. The controls at the internal border were only introduced between 04/07/2016 and 02/08/ 2016 due to NATO Summit, World Youth Day and visit of Pope as well as between 22/11/2018 and 16/12/2018 due to the climate conference (COPT).

5. Among others, Act on anti-terrorist activities (DZ.U. 2016 poz. 904) included inter allia, secret surveillance of conversations over devices, non-public places, correspondence, data contained on data carriers, telecommunications terminal devices, information and tele-information systems and parcels of a person who is not a Polish citizen in order to identify, prevent or combat crimes of terrorist character, ordered by the Head of the Internal Security Agency for a period not longer than 3 month and Regulation on the catalogue of incidents of a terrorist nature (Dz.U. 2016 poz. 1092) referred to 15 incidents connected to foreigners.

6. This is substantially different from the Polish civil society’s visible opposition to the recent changes in the abortion law, for example.

References

- Baker-Beall, C. (2010) “The European Union’s fight against terrorism: a critical discourse analysis”. Thesis. Loughborough University. Available at: https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/thesis/The_European_Union_s_fight_against_terrorism_a_critical_discourse_analysis/9467069

- Balzacq, T. 2005. “The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience and Context.” European Journal of International Relations 11 (2): 171–201. doi:10.1177/1354066105052960.

- Balzacq, T. 2008. “The Policy Tools of Securitization: Information Exchange, EU Foreign and Interior Policies*.” Journal of Common Market Studies 46 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00768.x.

- Balzacq, T. 2010a. “A Theory of Securitization:origins, Core Assumptions, and Variants.” In Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, edited by T. Balzacq, 1–30. London: Routledge.

- Balzacq, T. 2010b. “Enquiries into Methods: A New Framework for Securitisation Analysis.” In Securitization Theory : How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, edited by T. Balzacq, 31–54. London: Routledge.

- Balzacq, T., S. Léonard, and J. Ruzicka. 2016. ““Securitization” Revisited: Theory and Cases.” International Relations 30 (4): 494–531. doi:10.1177/0047117815596590.

- Barlai, M., B. Fähnrich, C. Griessler, and M. Rhomberg, eds. 2017. The Migrant Crisis: European Perspectives and National Discourses. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Barlai, M., and E. Sik. 2017. “A Hungarian Trademark (A “Hungarikum”): The Moral Panic Button.” In The Migrant Crisis: European Perspectives and National Discourses, edited by M. Barlai, et al., 147–169. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Barthwal-Datta, M. 2009. “Securitising Threats without the State: A Case Study of Misgovernance as A Security Threat in Bangladesh.” Review of International Studies 35 (2): 277–300. doi:10.1017/S0260210509008523.

- Bocskor, Á. 2018. “Anti-Immigration Discourses in Hungary during the “Crisis” Year: The Orbán Government’s “National Consultation” Campaign of 2015.” Sociology 52 (3): 551–568. doi:10.1177/0038038518762081.

- Buzan, B., O. Wæver, and J. de Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- CBOS (2015a) Polish Public Opinion. Immigrants in Poland, 7/2015. Available at: https://www.cbos.pl/PL/publikacje/public_opinion/2015/07_2015.pdf (Accessed 4 May 2020).

- CBOS (2015b) “Polish Public Opinion. Opinions about refugee crisis, 6/2015”. Available at: https://www.cbos.pl/PL/publikacje/public_opinion/2015/06_2015.pdf

- CBOS (2018) Stosunek Polaków i Czechów do przyjmowania uchodźców, Komunikat z badań 87/2018. Available at: http://www.cbos.pl (Accessed: 28 May 2019.

- Court of Justice of the European Union (2020) “Judgment in Joined Cases C-715/17, C-718/17 and C-719/17 Commission V Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, PRESS RELEASE No 40/20’”.

- Hansen, L. 2012. “Reconstructing Desecuritisation: The normative-political in the Copenhagen School and Directions for How to Apply It.” Review of International Studies 38 (3): 525–546. doi:10.1017/S0260210511000581.

- Horii, S. 2016. “The Effect of Frontex’s Risk Analysis on the European Border Controls.” European Politics and Society 17 (2): 242–258. doi:10.1080/23745118.2016.1121002.

- Huysmans, J. 2000. “The European Union and the Securitization of Migration.” Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (5): 751–777. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00263.

- Jäger, S., and F. Maier (2009) “Theoretical and Methodological Aspects of Foucauldian Critical Discourse Analysis and Dispositive Analysis”, In R. Wodak and M. Meyer (eds.) Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Second. SAGE, pp. 34–61.

- Karamanidou, L. 2015. “The Securitisation of European Migration Policies: Perception of Threat and Management of Risk.” In The Securitisation of Migration in the EU: Debates since 9/11, edited by G. Lazaridis and K. Wadia. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lazaridis, G., and K. Wadia, eds. 2015. The Securitisation of Migration in the EU. Databes Sinse 9/11. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Léonard, S., and C. Kaunert. 2019. Refugees, Security and the European Union. New York: Routledge.

- Léonard, S., and C. Kaunert. 2020. “The Securitisation of Migration in the European Union: Frontex and Its Evolving Security Practices.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851469.

- Lijphart, A. 1971. “Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method.” American Political Science Review 65 (3): 682–693. doi:10.2307/1955513.

- Neal, A. W. 2009. “Securitization and Risk at the EU Border: The Origins of FRONTEX.” Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (2): 333–356. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.00807.x.

- Polskie Radio24.pl (2018) Będą zachęty dla obcokrajowców na polskim rynku pracy - Gospodarka - polskieradio24.pl. Available at: https://www.polskieradio24.pl/42/273/Artykul/2077843,Beda-zachety-dla-obcokrajowcow-na-polskim-rynku-pracy (Accessed 10 September 2021).

- Sadowski, P., and K. Szczawińska (2017) “Poland’s Response to the EU Migration Policy”, In M. Barlai, et al. (eds.) The Migrant Crisis: European Perspectives and National Discourses. Berlin: LIT Verlag, pp. 211–234. Available at: https://books.google.es/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PhwmDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA59&dq=discourse+on+migration++during+the+crisis&ots=XonrJNgEnh&sig=nDq9Qg0yNS90LiG4be65wXl6XtQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=discourseonmigrationduringthecrisis&f=false (21 January 2022).

- Shepherd, L. 2008. Gender, Violence and Security: Discourse as Practice. London: Zes Books.

- Sperling, J., and M. Webber. 2019. “The European Union: Security Governance and Collective Securitisation.” West European Politics 42 (2): 228–260. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1510193.

- Squire, V. 2015. “The Securitisation of Migrations: An Absent Presence?” In The Securitisation of Migration in the EU. Debates since 9/11, edited by G. Lazaridis and K. Wadia, 19–36, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stritzel, H. 2007. “Towards a Theory of Securitization: Copenhagen and Beyond.” European Journal of International Relations 13 (3): 357–383. doi:10.1177/1354066107080128.

- Szalai, A., and G. Gőbl (2015). “Securitizing Migration in Contemporary Hungary”. Available at: https://cens.ceu.edu/sites/cens.ceu.edu/files/attachment/event/573/szalai-goblmigrationpaper.final.pdf (Accessed 22 April 2020).

- The Office for Foreigners (2020) MIGRACJE.GOV.PL. Available at: https://migracje.gov.pl/en/statistics/scope/world/type/statuses/view/tables/year/2015/ (Accessed 29 June 2020).

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2015. Europe’s Border Crisis: Biopolitical Security and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747024.003.0002.

- Vezovnik, A. 2018. “Securitizing Migration in Slovenia: A Discourse Analysis of the Slovenian Refugee Situation.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 39–56. doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1282576.

- Wæver, O. 2000. “The EU as a Security Actor. Reflections from a Pessimistic Constructivist on post-sovereign Security Orders.” In International Relations Theory and the Politics of European Integration : Power, Security and Community, edited by M. Kelstrup and M. Williams, 250–294. London: Routledge.

- Wilkinson, C. 2007. “The Copenhagen School on Tour in Kyrgyzstan: Is Securitization Theory Useable outside Europe?” Security Dialogue 38 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1177/0967010607075964.

- Zaun, N. 2018. “States as Gatekeepers in EU Asylum Politics: Explaining the Non-adoption of a Refugee Quota System.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 44–62. doi:10.1111/jcms.12663.