Abstract

The paper aims to elicit the understanding of process improvement (PI) project success by researching the effects of organisational – motivation and coordination in continuous improvement (CI) implementations in the financial services sector. The data analysed using structural equation modelling (SEM) comes from a sample of 198 survey respondents in financial service organisations that have implemented CI. This research shows that a strong organisational motivation is driving the embeddedness of PI methodology in, and alignment with the CI implementation of, the organisation and thus affecting PI project success. In addition, central coordination is found to affect the alignment of the organisation to the CI implementation activities and objectives and affects PI project success. These findings show how the organisational level constructs of organisational – motivation and coordination affect PI project success following the mediating constructs of alignment, embeddedness, and routinisation specifically in the context of financial services. Thus, the work provides a better understanding of how organisational level drivers affect the organisational context of PI projects and consequently affect PI project success. There is little empirical research on determinants of PI project success. Our work explains how factors in the organisational context in which PI projects take place are affecting project outcome.

1. Introduction

The organisational ability to continuously improve and optimise services, processes and products is defined by Bessant et al. (Citation1994) as ‘a company-wide process of focused and continuous incremental innovation’ and is commonly embodied by process improvement (PI) methodologies such as Lean, Total Quality Management, Six Sigma, Kaizen and Lean Six Sigma. These PI methodologies were developed in manufacturing environments and became widely adopted in service sectors (Sanchez & Blanco, Citation2014; Prashar & Antony, Citation2018), such as financial services (Vashishth et al., Citation2019). Irrespective of success stories, literature reports high CI implementation failure rates citing limited availability and quality (evidence) of directions for CI implementation processes (McLean et al., Citation2017; Bhamu & Singh Sangwan, Citation2014; Chakravorty, Citation2009). These mixed results provide the motivation for this research. This paper contributes to the empirical literature on continuous improvement (CI) implementation by examining how performance improvement is achieved. The effect of important organisational level drivers on the outcome of PI projects is tested by a sample of financial service organisations in Europe that have conducted CI implementation. The financial industry is subject to heavy changes due to increased regulatory requirements and the rise of non-traditional competition coming from among other the technology sector. This demands more reliable and faster digital processes. Additionally, the increases in price transparency and zero-interest policies posed by central banks have required more cost efficient operations. To cope with these challenges, many organisations in the financial sector have started to implement CI programmes and have adopted CI methodologies in totality (Hayler & Nichols, Citation2007). Therefore, this industry provides relatively many mature and hence interesting study objects.

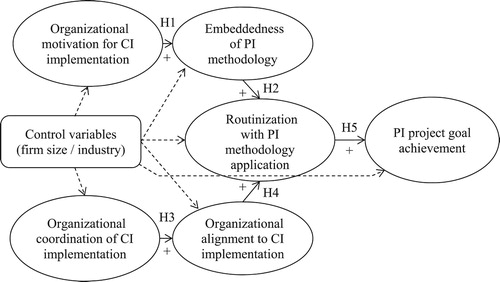

The process of implementing CI is recognised as a multilevel initiative that consists of activities at the organisational – and the project level (Nair et al., Citation2011; Linderman et al., Citation2010; Anand et al., Citation2009; Schroeder et al., Citation2008; Zu et al., Citation2008; Choo et al., Citation2007a; McAdam & Lafferty, Citation2004). On one hand there are organisational level activities, whereby senior management takes on pivotal challenges such as creating the motivation for change, setting adequate goals and subsequently coordinating the organisational change process. On the other hand, CI implementation is commonly shaped in a project-by-project fashion, designed to continuously seek and exploit process improvement opportunities (Matthews & Marzec, Citation2017). The actual improvements are delivered at the project level where project leaders are trained and take up a leading role. Thereby project leaders are positioned as change agents that have a driving role. Despite this multilevel character, most research on CI implementation adopts a single unit of analysis, either the organisational level (Shafer & Moeller, Citation2012; Swink & Jacobs, Citation2012) or at the project level (Linderman et al., Citation2003; McAdam & Lafferty, Citation2004; Linderman et al., Citation2006; Choo et al., Citation2007a; Zu et al., Citation2008; Schroeder et al., Citation2008). Interaction effects between organisational – and project level activities in CI implementations are researched by Nair et al. (Citation2011), who subsequently call for research into success at the project level and how this is affected by organisational level constructs. The purpose of this research is to understand how organisational – motivation and coordination at the organisational level affect PI project outcome. To understand how these two organisational level constructs affect PI project success, three mediating constructs are designed.

The structure of this paper comprises the conceptual development in Section 2. In this section the theory is discussed and hypotheses are drawn. Section 3 presents the research methods applied and provides discussion of the sample and survey – and construct development. Analysis of the data and SEM fit indices are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the results and the theoretical – and managerial implications and section 6 provides the conclusion, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Theoretical background

CI implementations are performed in organisations worldwide, ranging from manufacturing industries to professional service environments (Sanchez & Blanco, Citation2014). In order to better understand success or failure of CI implementation processes scholars started to investigate these processes and their outcomes. Systematic literature reviews have emerged in which critical success – and failure factors for CI implementation are summarised (Arumugam et al., Citation2014; Albliwi et al., Citation2014). Two interesting points stand out in these reviews. First, the reviews confirm that organisational level factors have an important effect: among others management commitment, links to corporate strategy and human resource management strategies are named. The other interesting point is the acknowledgement of project level factors, such as the rightful selection of projects, the adequacy of project leader skills, and the structured approach of PI projects (Arumugam et al., Citation2014; Albliwi et al., Citation2014). Hence CI implementation outcome is thus for one determined by organisational level factors and by factors at the project level.

2.1. The role of projects in continuous improvement implementation

Organisations that commence CI implementation commonly form a portfolio of PI projects that are selected and initiated based on their impact on corporate strategic objectives (Choo et al., Citation2007a; McAdam & Lafferty, Citation2004). Such PI projects are led by project leaders (e.g. for Six Sigma they are known as Green – or Black Belts) who have had extensive training. The improvement teams that support the project commonly comprises operational staff and other trained improvement specialists. The PI projects are structured by problem solving frameworks and apply statistical and non-statistical tools to learn about the problem, generate suitable improvements and achieve project goals (Zu et al., Citation2008; Linderman et al. Citation2006, Citation2003). Hence PI projects are a dominant manifestation of CI implementation in organisations and are recognised as an important determinant of organisation performance in CI implementations (Matthews & Marzec, Citation2017). Better understanding how organisational level activities affect operational level PI project results has important implications for managing CI implementations in organisations.

2.2. Organisational motivation and embeddedness

The first organisational construct of interest is the organisational motivation for implementing CI. Organisational motivation is about clarity of the need for CI implementation, and the degree of understanding and acceptance in the organisation (Albliwi et al., Citation2015; Kotter, Citation1995). Prior research has highlighted strong management commitment and the importance of making CI implementation part of business strategy as manifestations of organisational motivation (Arumugam et al., Citation2014; Albliwi et al., Citation2014; Laureani & Antony, Citation2018). The change management literature has recognised motivation for change as one of the first priorities (Kotter, Citation1995). As a strong and widely felt motivation is likely to influence how organisational actors will behave and affect PI project outcomes (see Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980, for their Theory of Reasoned Action), the argument here is that strong and lasting organisational motivation for CI implementation drives the embedding of PI methodologies in the organisation. Embeddedness of the methodology is about the degree of acceptance and adoption (McAdam & Lafferty, Citation2004). This line of reasoning is derived from research by McAdam and Lafferty (Citation2004). These authors have found that a holistic approach (inclusion of people and organisational criteria instead of a mere focus on tools) needs organisation wide support and commitment for the implementation, and this enabled the embedding of PI methodology in the organisation. Embedding is the process whereby organisational staff is empowered and provisioned with the appropriate PI methodologies and tools to be used in an empowered manner (Lleo et al., Citation2017). Thereby the organisations’ CI implementation objectives were found to be achieved (McAdam & Lafferty, Citation2004).

The positive effect of embedding PI methodologies on organisational performance is well supported by operations management literature (Belekoukias et al., Citation2014; Fullerton et al., Citation2003; Jayaram and Droge, Citation1999) and is also criticised by several researchers (Dow et al., Citation1999). Our primary interest is in how embedding of PI methodology leads to improved performance, and the research by Choo et al. (Citation2007a) on PI project execution revealed how learning and the creation of knowledge plays a pivotal role. The researchers revealed how a process of trial-and-error resulted in accumulated knowledge about how to best apply PI methodologies in practice. Based on this finding it is argued that the gradual embedding or adoption of PI – philosophies, principles and routines drives a change from an ‘old way’ of working a ‘new way’ of working where PI methodologies are part of everyday work at the process level. Thereby a growing number of regular staff involved in the CI implementation has gone through multiple learning cycles of how to apply PI methodology. Thereby knowledge (learning) and routinisation (experience) in the application of PI methodologies starts to grow. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed (see ):

H1. Organizational motivation for CI implementation is positively related to the degree of embeddedness of PI methodology in the organizational operations.

H2. Embeddedness of PI methodology in the organizational operations is positively related to the degree of organizational routinization in PI methodology application.

2.3. Organisational coordination and alignment

The second construct, organisational coordination, is about the degree of central coordination in CI implementation processes, manifested by the amount and centrality of coordinating staff (Schroeder et al., Citation2008). Coordinating activities are among others central corporate training programmes, communication strategies and leadership development. Earlier research emphasised the importance of coordinated selection and prioritisation of PI projects and training of PI project leads, which are important manifestations of coordination (Arumugam et al., Citation2014; Albliwi et al., Citation2014). Additionally, prior research recognised the importance of a parallel-meso CI management structure for the coordination of implementation efforts (Schroeder et al., Citation2008). Such a management structure is parallel to, but outside of, the organisational structure and integrates multiple levels of seniority by the use of teams, improvement specialists, steering committees and other structures, roles and methodologies (Schroeder et al., Citation2008). Here it is argued that the degree of central coordination by means of a central core-team positively impacts the degree of organisational alignment to the CI implementation. Organisational alignment boils down to the degree of PI methodology dissemination throughout the organisation in terms of business units involved, organisational staff trained and perceived importance of CI for the organisation. As suggested by Kwak and Anbari (Citation2006), organisation's need to have a clear communication plan and channels to motivate individuals to overcome resistance and to educate employees at different hierarchical levels on the benefits of CI implementation. Hence we argue that central coordination in CI implementation processes affects the degree of organisational alignment and consequently organisational routinisation. Subsequently it is argued that widespread organisational alignment and involvement of the organisation in CI implementation leads to more experience (routinisation) with PI methodology application throughout the organisation, operationalised by the construct of routinisation. Therefore we propose:

H3. Organizational coordination of the CI implementation is positively related to the degree of organizational alignment to the CI implementation.

H4. Organizational alignment to the CI implementation is positively related to the degree of organizational routinization in PI methodology application.

2.4. Organisational routinisation and improvement project success

Several empirical studies have related routinisation and improvement in ability over time (i.e. learning-by-doing; see Ittner & Larcker, Citation1997; Upton & Kim, Citation1998). Recent work by Easton and Rosenzweig (Citation2012) showed the effect of multiple types of routinisation on PI project success. The authors find that project leader routinisation and organisational routinisation are explaining the outcome of such projects. Here it is argued that organisational routinisation is determining project success, because the experience of an organisation with the application of PI methodology affects the ability and willingness of organisational staff to contribute, as project team – leads and members, to PI projects. As more operational staff, stakeholders and selected CI specialist involved in PI projects possess a degree of accumulated learning, experience, and knowledge on how to effectively execute PI projects, the chances for success are argued to be higher, hence:

H5. Organizational routinization in PI methodology application is positively related to the degree of PI project success.

3. Data and research methodology

3.1. Data sample

To test the proposed hypotheses, survey research amongst respondents from financial service organisations in Europe, Asia and North America comprising both banks and insurance firms was conducted (). The respondents were selected via the authors’ university CI alumni networks and professional social networks of LinkedIn and Xing. Searches for discussion forums containing ‘Lean’ or ‘Six Sigma’ or ‘TQM’ or ‘improvement’ in combination with ‘deployment’ or ‘implementation’ or ‘implementing’ in the title were performed.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (*including respondents from multiple subsectors).

The questionnaire was developed based upon a review of the existing literature related to CI implementation and PI project success. After designing the questionnaire, it was pre-tested by a total of eight CI practitioners for validity, clarity and user friendliness. In the process of data preparation, incomplete responses were completely deleted and the imputation of missing values for less than 5% of the remaining sample by means of single regression imputation in IBM AMOS 25 was performed (Kline, Citation2001). A total sample of 198 usable cases for data analysis remained (see ). To assure sample size is not jeopardising the reliability of the findings, composite factors were modelled following the final structural regression model design to reduce the number of free parameters and test model fit, which is good and indicates reliable results. Unfortunately, not all regions are equally represented in the final sample and we acknowledged this limits the generalizability of the results. Further, non-response bias might limit the generalizability of the findings, as the descriptive statistics show a relatively high level of homogeneity among the respondents.

3.2. Measures

Although sufficient research has addressed the topics of study, it was concluded that to date no research could provide appropriate scales for this specific study. Scales were developed according to the sequence of item generation, scale development and finally scale evaluation (Hensley, Citation1999). The first step in item generation was creating focus groups from the population to gain practical knowledge (Flynn et al., Citation1994). A total of 12 brainstorming sessions were facilitated, each comprising a minimum of 4 participants, where the theoretical definitions of the constructs were presented (). This first stage resulted in over 20 items per construct.

Table 2. Theoretical definition of constructs.

After having established a first set of items per construct, subsequent content validity assessment was performed. Teams of 4 experts that are active both in academics and in the field of study were grouped to perform double blind sorting of items to one of the five constructs (1–5 in ) (Hinkin, Citation1995). After the second round, 7–18 items per construct remained (see ). For construct 6, it was decided to compute this variable as the product of the degree of centrality – and full time equivalent staff that is coordinating the CI implementation. Thereby organisational coordination is measured as continuous variable and suitable for Maximum Likelihood structural regression modelling (Kline, Citation2001). Additionally, control variables were included. Firm size (number of employees, see ) and type of subsector (banking, insurance, or other) are added (Sousa & Voss, Citation2008).

Table 3. Questionnaire constructs and items, item factor loadings (>0.5), Cronbach's Alpha (α) values and convergent validity (>0.5) values.

After the data was gathered the stability of the scales was determined. Following Hensley (Citation1999), principal component analysis (Varimax rotation) in IBM SPSS 24, to assess factor loadings was applied (: PCA1). Loadings below 0.5 were eliminated (Kline, Citation2001). Items that remained after principal component analysis were subjected to Cronbach's Alpha (α) assessment (Cronbach, Citation1951). All the resulting values are well above the applied 0.6 threshold (Jones & James, Citation1979), meaning the constructs are all represented by high inter-item homogeneity and consistency.

Finally, common method bias was excluded by using Harman's single factor test (explained variance of 22.1%). Additionally, common latent factor analysis was performed and revealed common latent factor variance explanation of 0.026%. Hence, common method bias is not a concern (Richardson et al., Citation2009).

4. Data analysis

Structural equation modelling was performed in a sequence of path model identification, optimisation and finally structural regression model testing (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). Kline (Citation2001) is followed for reporting model fit indices. Reported and recommended values for model fit are presented in .

Table 4. Goodness of fit statistics of the model.

4.1. Path model identification and optimisation

Initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model identification was performed and convergence was achieved using maximum likelihood analysis after 11 iterations. Convergent validity assessment and modification indices revealed several items eligible for elimination (R2 < .5, see : CFA2) and high covariance between items (indicated by ‘+’ in ). For the constructs motivation and embeddedness, convergent validity R2 values slightly below .5 were accepted to ensure the construct are minimally measured by 3 items and ensure model reliability (Kline, Citation2001). To exclude the risk of non-normality, bootstrapping was performed (200 samples) and resulted in good final CFA model fit indices (see ). Finally, discriminant validity of the constructs was good (all constructs < .85 correlated) (Kline, Citation2001).

4.2. Structural regression model identification and optimisation

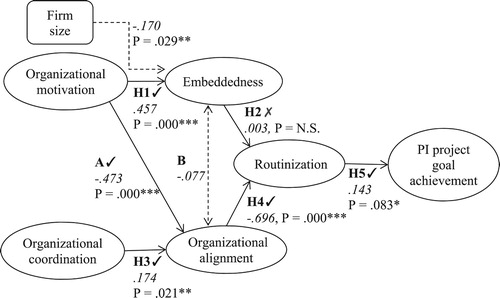

Following sufficient CFA model fit, a structural regression (SR) model to test the hypothesised causal relations was developed. The model modification indices signalled potential direct effects between embeddedness and organisational alignment, and between organisational motivation and organisational alignment. Testing both effects simultaneously yielded only deteriorated model fit for removing embeddedness – alignment and not for motivation – alignment. Hence, the effect of embeddedness – motivation on model fit seems stronger. For the intermediate SR model, the hypothesised relations were followed and the discovered direct positive effect of motivation on alignment was added (‘A’ in ; organisational alignment is reversely scaled), which resulted in good model fit. As presented in , four of the five hypotheses are confirmed.

4.3. Analysis of the results and further model optimisation

First, we found that the degree of organisational motivation to implement CI significantly and positively influences the degree of embeddedness of PI methodology (Hypothesis 1 confirmed), which subsequently does not significantly influence routinisation (Hypothesis 2 not confirmed). As discussed before, embeddedness is not directly related to organisational alignment. Model comparison with an indirect relation (correlation) between embeddedness and alignment yields non-significant model deterioration and better model fit indices. Hence, we concluded that embeddedness indirectly affects routinisation and is included in the model (‘B’ in , negatively correlated). Although the effect is minor, the more embedded PI methodology is, the less the important further dissemination of CI in the company is perceived to be. A control variable for firm size (ranging from 1–5) was added to test for common variance and revealed relatedness to embeddedness. The larger the organisation, the lower the degree of embeddedness is expected to be. Explanation for this phenomenon is rather intuitive, as larger firms have larger amounts of organisational staff that must be reached, trained, and adhered to adopting PI methodology. Additionally, controlling for financial subsector yielded insufficient model fit. It was concluded that the model and sample did not allow for group comparison. Final SR model fit is good (). The resulting model is presented in . Each path in the figure represents the corresponding hypothesis, the estimated path coefficient and significance of the relation.

Next it was found that coordination of the CI implementation significantly affects organisational alignment (Hypothesis 3 confirmed). This effect only occurs when the discovered direct effect between organisational motivation and alignment (‘A’ in ) is added. Hence, when the organisational motivation to implement CI is not present, coordination has no significant effect on the degree of organisational alignment. Further, the effect of coordination on alignment slightly deteriorates when the indirect relation with organisational embeddedness (‘B’ in ) is included. Hence, when embeddedness of PI methodology in the organisation is lower, coordination combined with a strong motivation is positively affecting the degree of organisational alignment to the CI implementation and vice versa.

Third, the degree of organisational alignment to the CI implementation is significantly affecting routinisation (Hypothesis 4 confirmed). This relation is positive as organisational alignment is inversely scaled. Finally, routinisation is found to significantly and positively affect PI project goal achievement (Hypothesis 5 confirmed).

5. Discussion and future research directions

The objective of this research is to study the effects of organisational motivation and coordination on PI project success in CI implementations. This research contributes to the literature on understanding the effects of the organisational context in which PI projects are executed.

The first contribution is that strong and widely shared organisational motivation to engage in CI implementation positively influences the embedding of PI methodology in organisations. This implies that a strong and widely felt motivation to implement CI leads to greater adoption and embedding of PI methodologies by organisational staff in day-to-day operations. This effect is negatively related to firm size: achieving higher degrees of embeddedness need more organisational motivation in larger firms (the findings suggest roughly above 2000 employees). The concept of motivation as prerequisite for organisational transformation processes is widely acknowledged (Todnem By, Citation2005). For Lean Six Sigma implementation specifically, the need for change has been recognised as first implementation step by Kumar et al. (Citation2011), Antony et al. (Citation2016) and McLean and Antony (Citation2017). Their findings are corroborated by this research and provide empirical insight into factors that specifically create a compelling need for change. Future research should focus not so much on identifying if – but more on extending our understanding on what else – is most persuasive in creating the organisational motivation for CI implementation.

Evidence for the subsequent effect of embeddedness on routinisation is not found. Greater embeddedness is however related to the degree of organisational alignment. Our second contribution is in complementing previous findings by McAdam and Lafferty (Citation2004). In their research on Six Sigma implementation, the importance of embedding PI methodologies and tools in organisational staff their day-to-day operations is signalled (also previously recognised by Wilkinson et al., Citation1997). The authors report that by extending the scope of the implementation from just solving the problem or defect areas (the instrumentalist approach) to empowering organisational staff in resolving and preventing root causes of defect areas (joint people and process approach), CI objectives were achieved. This finding provides understanding of how the empowerment of organisational staff may contribute to PI project goal achievement. Namely by first creating a degree of management attention and perceived importance (alignment), leading to acceptance and consecutive routinisation or experience of organisational staff with PI methodology.

Third, the results show a positive causal relation between the degree of coordination of the CI implementation and the degree of organisational alignment to the CI implementation. Our contribution lays in providing empirical support and corroboration of prior case based research that acknowledged the value of central coordination by selection, prioritisation and coordination of PI projects (Schroeder et al., Citation2008; Brun, Citation2011). Previous research proposed that a parallel-meso hierarchal structure where business leaders initiate and review PI projects and where more senior project leaders coach and support junior project leaders creates value in CI implementations (Schroeder et al., Citation2008). We found that in case of little motivation to implement CI, the effect of a core-team leading the implementation becomes insignificant. Future research opportunities lay in understanding how the value of central coordination is created and should focus on the specific activities or roles that central coordination fulfils over time.

The fourth contribution is the finding that increasing organisational alignment affects the degree of routinisation or experience with PI methodology application by organisational staff, and positively affects PI project goal achievement. Hence, increased organisational staff experience with PI methodology and PI projects is positively affecting PI project outcome. Research by Easton and Rosenzweig (Citation2012) examined how various types of experience affect the success of PI projects and concluded that especially experience of the project leader and organisational experience is crucial. Our findings corroborate the importance of experience in the organisation, though does not specify the type of experience and the exact workings. Prior case-based research did acknowledge that routinised PI methodology application is associated with knowledge creation and learning (Choo et al., Citation2007b; Linderman et al., Citation2010). Future research opportunities lay in further empirical examination and understanding of how increased organisational routinisation leads to the success of PI projects.

6. Conclusions, implications and limitations

This study contributes to the empirical knowledge of PI project outcome in CI implementations. Specifically, it showed the positive effects of strong organisational motivation and central coordination on PI project success resulting from organisational alignment to – and experience with PI methodology.

6.1. Implications

The study has several implications for managing the CI implementation process. First, CI implementation leaders are advised to ensure strong organisational motivation and support for the implementation. Finding a convincing and compelling need to engage in the organisational transformation process is prerequisite for PI project success. Second, the installation of a central core-team directing and overseeing the CI implementation process is advised. It is important to maintain focus on the strength of the perceived need for change, as this is conditional for the effectiveness of a central core team. Finally, a focus on embedding PI methodology influences the level of experience with PI methodology application, and thereby supports PI project goal achievement. Additionally, when the degree of embeddedness increases, the effectiveness of a central core-team decreases. Hence, a focus on gradually shifting the responsibility to drive and lead further CI implementation from a central core-team to regular business management seems wise, on the condition that a certain degree of embedding of – and routinisation with PI methodology is achieved.

6.2. Limitations

Although attention is paid to developing valid scales, the process of model identification revealed several items that displayed limited explanatory power for their respective constructs. These construct validity concerns limit the reliability of the findings and identify a need for further research and strengthening of the scales. Another limitation is the generalizability of the results. Despite the fact that data from multiple continents was gathered, it was not possible to make comparisons between different groups due to the dominancy of German and Dutch respondents from the financial services sector. Hence the applicability of the findings for CI implementations outside of Western Europe and in other industries remains uncertain. Future research opportunities lay in larger samples that are more evenly distributed geographically. This will help in meaningful explanation of differences due to cultural inherencies.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, B.A. Lameijer. The data are not publicly available due to participant privacy restrictions (presence of information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Albliwi, S., Antony, J., Abdul Halim Lim, S., & van der Wiele, T. (2014). Critical failure factors of Lean Six sigma: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 31(9), 1012–1030. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-09-2013-0147

- Albliwi, S. A., Antony, J., & Lim, S. A. H. (2015). A systematic review of Lean Six Sigma for the manufacturing industry. Business Process Management Journal, 21(3), 665–691. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-03-2014-0019

- Anand, G., Ward, P. T., Tatikonda, M. V., & Schilling, D. A. (2009). Dynamic capabilities through continuous improvement infrastructure. Journal of Operations Management, 27(6), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.02.002

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Ansari, SM, Fiss, PC, & Zajac, EJ. (2010). Academy of management review (Vol. 35, pp. 67–92).

- Antony, J., Vinodh, S., & Gijo, E. V. (2016). Lean six sigma for small and medium sized enterprises: A practical guide. CRC Press.

- Arumugam, V., Antony, J., & Linderman, K. W. (2014). A multilevel framework of Six Sigma: A systematic review of the literature, possible extensions, and future research. Quality Management Journal, 21(4), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2014.11918408

- Belekoukias, I, Garza-Reyes, JA, & Kumar, V. (2014). The impact of lean methods and tools on the operational performance of manufacturing organisations”. International Journal of Production Research, 52(18), 5346–5366. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.903348

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., & Gilbert, J. (1994). Mobilizing continuous improvement for strategic advantage. EUROMA, 1, 175–180.

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., & Gilbert, J. (1996). Learning to manage innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 8(1), 59–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329608524233

- Bhamu, J., & Singh Sangwan, K. (2014). Lean manufacturing: Literature review and research issues. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34(7), 876–940. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-08-2012-0315

- Brun, A. (2011). Critical success factors of Six Sigma implementations in Italian companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 131(1), 158–164. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.05.008

- Chakravorty, S. S. (2009). Six Sigma programs: An implementation model. International Journal of Production Economics, 119(1), 1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.01.003

- Choi, B., Kim, J., Leem, B. H., Lee, C. Y., & Hong, H. K. (2012). Empirical analysis of the relationship between Six Sigma management activities and corporate competitiveness: Focusing on Samsung group in Korea. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(5), 528–550. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211226489

- Choo, A. S., Linderman, K. W., & Schroeder, R. G. (2007a). Method and psychological effects on learning behaviors and knowledge creation in quality improvement projects. Management Science, 53(3), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0635

- Choo, A. S., Linderman, K. W., & Schroeder, R. G. (2007b). Method and context perspectives on learning and knowledge creation in quality management. Journal of Operations Management, 25(4), 918–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.08.002

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Dow, D., Samson, D., & Ford, S. (1999). Exploding the myth: Do all quality management practices contribute to superior quality performance? Production and Operations Management, 8(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.1999.tb00058.x

- Easton, G. S., & Rosenzweig, E. D. (2012). The role of experience in six sigma project success: An empirical analysis of improvement projects. Journal of Operations Management, 30(7-8), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.08.002

- Flynn, B. B., Schroeder, R. G., & Sakakibara, S. (1994). A framework for quality management research and an associated measurement instrument. Journal of Operations Management, 11(4), 339–366. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(97)90004-8

- Fullerton, R. R., McWatters, C. S., & Fawson, C. (2003). An examination of the relationships between JIT and financial performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21(4), 383–404. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(03)00002-0

- Hatch, N. W., & Mowery, D. C. (1998). Process innovation and learning by doing in semiconductor manufacturing. Management Science, 44(11-part-1), 1461–1477. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.44.11.1461

- Hayler, R., & Nichols, M. (2007). Six Sigma for financial services: How leading companies are driving results using lean, six sigma, and process management. McGraw Hill Professional.

- Hensley, R. L. (1999). A review of operations management studies using scale development techniques. Journal of Operations Management, 17(3), 343–358. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00051-5

- Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management, 21(5), 967–988. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639502100509

- Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (1997). The performance effects of process management techniques. Management Science, 43(4), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.43.4.522

- Jackson, D. L. (2003). Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N: Q hypothesis. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(1), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_6

- Jayaram, J., Droge, C., & Vickery, S. K. (1999). The impact of human resource management practices on manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(99)00013-3

- Jones, A. P., & James, L. R. (1979). Psychological climate: Dimensions and relationships of individual and aggregated work environment perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23(2), 201–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(79)90056-4

- Kennedy, M. T., & Fiss, P. C. (2009). Institutionalization, framing, and diffusion: The logic of TQM adoption and implementation decisions among US hospitals. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 897–918. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44633062

- Kline, R. B. (2001). Principles and practices of structural equation modelling. The Guilford Press.

- Kotter, J. P. (1995, March-April). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, pp. 59–67.

- Kumar, M., Antony, J., & Tiwari, M. K. (2011). Six Sigma implementation framework for SMEs–a roadmap to manage and sustain the change. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5449–5467. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.563836

- Kwak, Y. H., & Anbari, F. T. (2006). Benefits, obstacles, and future of six sigma approach. Technovation, 26(5-6), 708–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.10.003

- Laureani, A., & Antony, J. (2018). Leadership–a critical success factor for the effective implementation of Lean Six Sigma. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(5-6), 502–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2016.1211480

- Linderman, K. W., Schroeder, R. G., & Choo, A. S. (2006). Six Sigma: The role of goals in improvement teams. Journal of Operations Management, 24(6), 779–790. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.08.005

- Linderman, K. W., Schroeder, R. G., & Sanders, J. (2010). A knowledge framework underlying process management. Decision Sciences, 41(4), 689–719. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00286.x

- Linderman, K. W., Schroeder, R. G., Zaheer, S., & Choo, A. S. (2003). Six Sigma: A goal-theoretic perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 21(2), 193–203. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00087-6

- Lleo, A., Viles, E., Jurburg, D., & Lomas, L. (2017). Strengthening employee participation and commitment to continuous improvement through middle manager trustworthy behaviours. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(9-10), 974–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1303872

- Matthews, R. L., & Marzec, P. E. (2017). Continuous, quality and process improvement: Disintegrating and reintegrating operational improvement? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(3-4), 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1081812

- McAdam, R., & Lafferty, B. (2004). A multilevel case study critique of Six Sigma: Statistical control or strategic change? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(5), 530–549. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570410532579

- McLean, R. S., & Antony, J. (2017). A conceptual continuous improvement implementation framework for UK manufacturing companies. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(7), 1015–1033. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-02-2016-0022

- McLean, R. S., Antony, J., & Dahlgaard, J. J. (2017). Failure of continuous improvement initiatives in manufacturing environments: A systematic review of the evidence. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(3-4), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1063414

- Nair, A., Malhotra, M. K., & Ahire, S. L. (2011). Toward a theory of managing context in six sigma process-improvement projects: An action research investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 29(5), 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.11.014

- Prashar, A., & Antony, J. (2018). Towards continuous improvement (CI) in professional service delivery: A systematic literature review. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1438842

- Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109332834

- Sanchez, L., & Blanco, B. (2014). Three decades of continuous improvement. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(9-10), 986–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.856547

- Schroeder, R. G., Linderman, K. W., Liedtke, C., & Choo, A. S. (2008). Six Sigma: Definition and underlying theory. Journal of Operations Management, 26(4), 536–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.06.007

- Shafer, S. M., & Moeller, S. B. (2012). The effects of Six Sigma on corporate performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 30(7-8), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.10.002

- Sousa, R., & Voss, C. A. (2008). Contingency research in operations management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.06.001

- Swink, M., & Jacobs, B. W. (2012). Six Sigma adoption: Operating performance impacts and contextual drivers of success. Journal of Operations Management, 30(6), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.05.001

- Todnem By, R. (2005). Organizational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010500359250

- Upton, D. M., & Kim, B. (1998). Alternative methods of learning and process improvement in manufacturing. Journal of Operations Management, 16(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00028-4

- Vashishth, A., Chakraborty, A., & Antony, J. (2019). Lean Six Sigma in financial services industry: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(3-4), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1308820

- Wilkinson, A., Godfrey, G., & Marchington, M. (1997). Bouquets, brickbats and blinkers: Total quality management and employee involvement in practice. Organization Studies, 18(5), 799–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069701800505

- Zu, X., Fredendall, L. D., & Douglas, T. J. (2008). The evolving theory of quality management: The role of Six Sigma. Journal of Operations Management, 26(5), 630–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.02.001