Abstract

Although leadership is consistently found to be the main success factor for lean transformations, our knowledge about how to develop the necessary leadership competences at the level of the individual and the organisation remains limited. Based on an action-research study of lean leadership development in a Norwegian high-tech manufacturer, this article proposes an integrated model for how to develop corporate lean leadership. The model combines earlier research on ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ leadership competencies and individual versus collective competency development in a two-dimensional framework, which highlights four areas of intervention. We argue that conventional lean leadership training should be supplemented by insights and practices from human resource management and organisational development. Hence, lean professionals (coaches and trainers) should reach out to HR-professionals often organised in different functional departments. The model might guide future practical interventions. We encourage further research to investigate the model with respect to its wider applicability.

Introduction

Research has consistently identified leadership as the main success factor for lean transformations, as well as the primary cause for failed transformations (Netland et al., Citation2019). A growing literature investigates which leadership behaviours are more aligned with the lean concept (e.g. Dombrowski & Mielke, Citation2013; Liker & Convis, Citation2012; Seidel et al., Citation2017) and how those behaviours differ from traditional leadership (Emiliani, Citation2003). Universal and highly abstract models of lean leadership (e.g. Liker & Convis, Citation2012; Spear, Citation2004) have been supplemented by more specific models on how those lean leadership principles should be enacted at different hierarchical levels (Netland et al., Citation2019) or at different stages in the transformation process (Holmemo et al., Citation2018; Poksinska et al., Citation2013).

Despite the significance of lean leadership, the question about how the necessary leadership competencies are developed at the level of the individual and the organisation has received only marginal attention in the academic literature (Sisson, Citation2019; Spear, Citation2004). In practice, organisations seem to rely on conventional leadership development (Lacerenza et al., Citation2017), which however useful, might not be sufficiently adapted to the lean content. Specifically, courses and training sessions may fall short of inducing the required cultural change (Dahlgaard & Dahlgaard-Park, Citation2006) or fostering an integrated management approach (Danese et al., Citation2018).

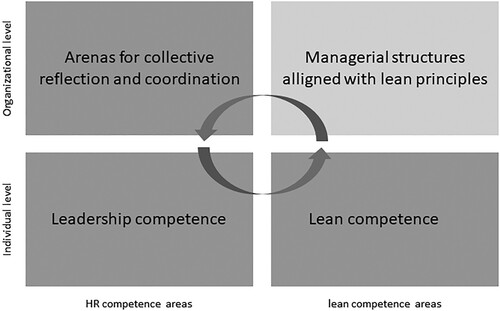

In this article the question of how to build lean leadership is approached through an action-research study (Shani & Coghlan, Citation2021). Over a period of two years, the authors followed and intervened in the lean transformation of a Norwegian high-tech manufacturer, which involved three levels of corporate managers. As the managers’ appreciation of lean leadership and their own roles as change agents grew, it became clear that developing corporate lean leadership involved working along two dimensions. First, along the competency dimension, leaders should learn both the lean principles and general leadership competencies. Second, along the organisational dimension, individual development should be supplemented by arenas for collective alignment and measures to eliminate structural and cultural barriers for lean. We suggest that when both dimensions are attended to over time, companies may succeed in building lean leadership.

Our findings advance current knowledge by investigating a relatively unexplored phenomenon. By proposing an integrated model for corporate lean leadership, we synthesise earlier research on ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ leadership competencies and individual versus collective competency development. The framework may guide practical interventions. Specifically, we suggest that lean leadership development should integrate insights and practices from human resource management on individual development and insights from change management on organisational development.

Lean leadership

The popularity of lean flourished after Womack et al. (Citation1990) described the production system of Toyota Motor Company, and Womack and Jones (Citation1996) further presented it as a universal solution for improved productivity and quality independent of industry or geography. Lean as an organisation concept continues to evolve and propagate across sectors in organisations worldwide, evidenced with a growing number of publications on the subject (Benders et al., Citation2019; Danese et al., Citation2018; Netland & Powell, Citation2017).

Liker and Convis (Citation2012) summarised four prescriptions for Toyota-way lean leadership: (1) commit to self-development towards certain lean principles (2) coach and develop others (3) support daily improvement and (4) create vision and align goals. The literature on lean beyond Toyota suggests aiming for a systemic and integrated managerial approach containing both ‘hard’ tools and measurable benefits of cost and speed, and ‘soft’ practices and qualities like quality of work and commitment (Danese et al., Citation2018). Emiliani (Citation2003) also underlines that managers’ beliefs, behaviours and competencies should be aligned, so that lean fosters humble, relation-building, explorative and development-oriented leaders.

There seems to be consensus that coaching, supporting, being visible and attendant, and clear and consistent are favourable to exercising lean leadership (Laureani & Antony, Citation2017; van Assen, Citation2018). Furthermore, van Dun et al. (Citation2017) argue that operative leaders need high-level relational skills, such as active listening and encouraging improvement to succeed. Nevertheless, Tortorella et al. (Citation2018) found that task-orientation is essential in leading lean organisations successfully. In conclusion there are arguments supporting elements of both transformative and transactional leadership in lean leadership practice (Laureani & Antony, Citation2017).

We have seen that lean leadership consists of competencies and behaviours which may not be readily found in most organisations embarking on lean transformations. An important question follows immediately: how can these competencies and behaviours be developed?

Developing lean leadership

Early treatments of how lean leadership develops emphasised Toyota’s strong corporate culture, and how novice or prospective managers were socialised into a distinct way of thinking and behaving under the guidance of superiors or sensei (Ballé et al., Citation2019; Spear, Citation2004). Hence, the development of lean leaders appears as an ongoing everyday activity within the managerial hierarchy, supported by predictable employment and career paths (Ingvaldsen & Benders, Citation2016). However, as stated by Holmemo et al. (Citation2018), contemporary Western organisations are not structured like Toyota, and cannot copy Toyota’s success by emulating their practices. Although coaching through the hierarchy may be a universally sound approach (Rother, Citation2010), Western organisations will likely rely primarily on internal or external leadership development courses (Gilpin-Jackson & Bushe, Citation2007; Lacerenza et al., Citation2017).

Due to methodological difficulties, research has not yet established whether leadership development programmes have a positive effect on leadership performance and organisational outcomes. Yet, Lacerenza et al.’s (Citation2017) meta-analysis of publications between 1951 and 2014 concludes on an optimistic note: as long as programmes are based on needs analysis, have holistic content balancing technical and inter-relational leadership topics, are designed with multiple delivery methods (especially practical training and feedback), have a structured and face-to-face based form, and happen on-site, one can expect effects on both the individual- and organisational levels.

Sisson’s (Citation2019) action research project was designed with best practices for training transfer and demonstrated a positive outcome of front-line managers involving employees in daily improvement activities through the application of lean principles. Similarly, we have been seeking in-depth knowledge on how to design an effective development programme for lean leadership. We have been building on the best practices described by Lacerenza et al. (Citation2017) using action research to tailor the programme to the needs of the participating managers.

Research approach

This article reports an action-research study from a global technology company situated in Norway. Action research implies several iterations of a participatory processes between researchers and organisational members which support organisational development and contribute to building scientific knowledge (Shani & Coghlan, Citation2021). After two years of inquiry, we take a step back to study our common learning process for scientific validation and contribution.

The research was initiated through a national research programme between our university and several manufacturing companies in Norway. In this company our aim was to increase the leadership competence and responsibility in the company’s unfolding lean programme. Our case company has over 700 employees worldwide and approx. 430 employees located at the divisional headquarters in Norway. The company is part of a larger Norwegian organisation with over 10,000 employees located in more than 30 countries worldwide. The lean programme manager has had responsibility of developing and deploying the lean programme across the division since 2014. The lean programme consists of several lean principles to guide the lean transformation as well as a model for lean leadership based on six lean leadership practices: Hoshin Kanri, Kaizen, A3 Management, Coaching, Daily stand-up meetings and Gemba walks. Before our interventions, these principles had been presented in a brochure and on posters at the divisional headquarters, and there had been several training sessions as well as implementation activities. The practical challenge was to increase the managers’ perceived ownership of the lean leadership principles and more generally, the lean transformation.

Our collaboration was planned as an open-ended series of leadership seminars with training and team reflection between seminars. The intervention period lasted from January 2017 to April 2019, during which we had four seminars. The participants were representatives from three levels of the management hierarchy, from frontline supervisors to the division manager. The research team planned the seminars together with the lean programme manager on basis of the feedback and the reflections from the managers in the development programme. The researchers attended every seminar as observers, having a passive role apart from in seminar 2, where one of us gave a lecture in change management. The researcher team evaluated the seminars during the intervention period. This was done by first collecting the participants’ instant reactions at the end of each seminar by a questionnaire, adopted from Grohmann and Kauffeld (Citation2013). The questionnaire, with the original English-language items is shown in . 4–7 weeks later, we followed up by an individual Skype interview (video and audio) addressing learning outcomes, practical transfer and identified learning needs. These responses formed important input in planning the subsequent seminars in the series. Following the last seminar, the questionnaire was not distributed, but the interviews were performed after 2–3 weeks.

Table 1. Reaction survey.

At the end of the intervention period we analysed our 37 transcribed interviews and field notes from seminars and meetings. These were coded in Nvivo12. Nodes were analysed thematically (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), and topics concerning participants’ reflections on leadership responsibilities and development needs were grouped for each seminar and used to assess the progress during the intervention period.

The lean-leadership journey

During the two-year period, the managers and the researchers embarked on a journey to develop lean leadership by recurring seminars. In the following we present contemporary reflections and retrospective insights as a chronological process illustrated with quotations from the interviews.

Seminar 1: Nice repetition of mandatory production methods

The first seminar we participated was held by the lean programme manager. It was built around the lean leadership platform with the six previously identified practices. The programme manager communicated a wide understanding of lean leadership and focused on how the lean methods should be used in coaching the workers. Nevertheless, the tangible aspects of lean and the practical lean tools attracted the focus of the attending managers both during and after the seminar. The managers discussed the applicability of the lean methods in the operational practice and in the interviews, most of them expressed that the seminar was a repetition, although a necessary one as the methods were not fully implemented and risked being forgotten. As one of the participants explained:

Well, I did not feel I learned something new, but the seminar helped to refresh my memory. Especially as we do not have the routines in our daily work, it is nice to have repetition on how to use the tools.

Several signalled that they had been through the lean training exercises (e.g. folding paper planes) repeatedly during the last years. Some of them had already established daily stand-up meetings prior to the seminar and a few used A3 problem solving on smaller issues. No one reported that the seminar had led to changes in their behaviour.

As the managers were leaving the seminar, they were overall quite pleased (Average 6.9/STD 1.4 on the statement ‘I enjoyed the training very much’). Having time to train and reflect together with peers on three levels was a welcomed break from the everyday routine. They appreciated the opportunity for repetition as illustrated by one of managers:

I believe it’s really important to have occasional seminars like this as a reminder. Otherwise lean will sink into oblivion.

Nonetheless, after some weeks the majority did not remember much of the main messages, they had not had time to do their ‘homework’ and reported no practical changes resulting from the seminar.

I remember deciding to start [problem solving method] as I had thought about it for a while. Otherwise … I don’t remember much, I’m afraid. (…) [why?] (…) My workday is just so busy going in and out of meetings, I have no time to reflect on things.

Our impression was that the managers took little responsibility in the lean implementation and did not reflect much on their role as leaders. Some of the participants found it unfair that their employees did not receive the same amount of training from the programme without considering self-ownership for this:

I have been through this [training] five times while my employees have not been involved even once. It doesn’t help if I see the value [of lean] if 13 people don’t.

Several said they were too insecure to lead mandatory lean processes against resistance from their subordinates, and requested more assistance from management or the lean programme manager in their lean activities on the shop floor:

I know [program manager] has a lot to do, he says he will be there to help, but when I need him, he is not. Then I feel insecure. I get through it somehow, but it’s not optimal.

Some of them [managers] have been workers and became managers. It is important to raise their awareness of their responsibility, and that the whole management group gathers and experiences support for a common grounds and attitude [towards lean].

Seminar 2: An arena for discussing problems

After our evaluation of the first seminar, the focus at the next seminar four months later was changed from ‘how to manage doing lean’ to ‘how to make improvements happen’. The seminar design was more spacious with focus on change management and problem solving, where we steered the problem-solving exercises towards issues of coordination between units and making sustainable changes. The participants were marginally happier than with the previous seminar (average 7.3/STD 1.5), and in the follow-up interviews, the managers expressed their appreciation of an arena for common discussion and reflection around real problems. The following quote is representative:

I absolutely see the need for gatherings where we discuss problems and develop a common understanding of how things should be done.

We heard several similar reflections. Firstly, the managers had seen that they could get feedback and help in solving specific problems within their areas of responsibility and receive advice from peers with more lean experience. Secondly, some managers underlined the importance of solving shared problems and improving the processes through coordinated actions. Finally, we found arguments for the need for an arena to develop a stronger culture around the transformation and to receive support for facing resistance that may present itself among their employees. Although the material showed that the managers were still asking for technical training in tools for both lean and managerial problem solving, we noticed an increased awareness of their responsibilities as leaders and the need for developing leadership competence. One participant said:

You can tidy your workstation, and everything looks fine. But when it comes to the things that really matter in their workday, they meet adversity. Then it is hard for a manager to motivate his people.

The division manager challenged us to push managerial responsibilities even harder:

Some managers are brilliant in defining problems, but they have no solutions. I think we ought to work on this matter. It is too easy to pass every problem to their seniors.

Seminar 3: From lean practices to leadership behaviour

At this point we started investigating the records of leadership development in the company. The division manager told us that he had been following several corporate-wide leadership development programmes during the years, but due to cutbacks, managers on lower levels had not been given such training in recent years. Together with the lean programme manager we contacted the corporate human resource (HR) function, which hosted the providers of the leadership development programme within the organisation. Initially, the leadership development experts seemed vigilant towards a lean-programme training manager – was this properly performed according to the corporate leadership platform? However, they became intrigued by the idea of a collaboration as a pilot study and decided to participate in two subsequent seminars.

Inviting the HR Leadership development team changed the focus during the next lean leadership seminar. The leadership training part focused on leadership as behaviour on the individual level, and concerned relational-, communication- and coaching skills. The participants were invited to reflect on their different personality types (marked by colours). The managers also reflected over how people learn from experience and reflection, and how the participants could themselves be more self-conscious in communication and employee feedback.

We observed that even if we had succeeded in bringing the divisional lean programme manager and corporate HR leadership development experts in the same room and ‘on the same page’, there were still two independent messages to the participants, one about lean and another about leadership. This point of view was reflected in most managers’ reflections:

I separate those two with the best intentions. I focus on lean and I focus on leadership. Independently.

Lean was, as another manager put it: ‘a toolbox for best practice leadership’. Given this perspective, the managers urged for input concerning leadership in general and were quite pleased with this turn in the seminar series (average 8.3/STD 1.3). This time, the following period was filled with signs of individual reflection, collective discussions, and furthermore, actions from the management group. The managers reported that they found it useful to reflect on the different personality types in practical situations, and a couple used their ‘colour’ to explain their own reactions and decisions in the interviews. One told that the different personality types had become a common language in the management team that they referred to during internal discussions. One manager told us:

It is useful to get feedback on how others perceive your behaviour and the differences between blue, red and green personalities (…) We [team of managers] sat down and discussed it, it was highly relevant, and even cleared up some misunderstandings.

With a clear perspective of leadership being detached from lean, the managers reported instances where internal communication and reflection on different personal preferences had brought up problems to be systematically solved and coordinated throughout the value stream as illustrated by this example:

Communication is essential. But, I can agree with my manager, and him partly with his. On the way up, information disappears. We need to improve our documentation practices. The manager on the top distributing the resources cannot see the problem without sufficient documentation.

Seminar 4: Lean as a corporate leadership system?

The increased level of discussions about the meaning of ‘lean leadership’ and the differences between that and the corporate leadership platform that HR had communicated challenged both the HR team and the lean programme manager to collaborate more closely in preparing the final seminar. This time, the relevance of leadership skills for living the lean principles or implementing the lean tools worked its way to the surface, as well as the understanding that lean leadership supported the corporate leadership platform. Reflecting on their learning, a couple of the managers expressed that these leadership skills should have been the foundation for being able to implement lean in their teams, and that they now were more competent in adapting the main message from the lean leadership programme.

Yet, these few days of reflection and training did not work wonders. Our interpretation of the data is that we see a movement in level of awareness and reflection of being leaders after the two last seminars and a growing maturity towards lean leadership However, as we packed up the last seminar, the lean programme manager proclaimed: ‘We are ending this story with a huge cliff hanger, God knows what will happen next?!’

His concern was supported by the interview material. We had identified further needs for repeated practical training sessions, both concerning lean techniques and leadership skills, and shared arenas for collective reflection and problem solving. Corporate HR had been involved and the leadership development programme had been aligned with the principles of lean leadership, but still the lean transformation strategy was divisional and solutions to problems identified by divisional managers were owned on a corporate level.

The participating managers persistently expressed concerns about obstacles beyond their control and beyond what could be dismissed as disclaimers of responsibility for successful lean implementation. Issues like the physical layout of the division site being unsuitable for manufacturing activities, lack of alignment in current infrastructure (e.g. ERP-system), a quality system which prohibited the same person that reported the problem from owning the solution, and so on.

It is chaos here and we have no support from the top right now (…) There are so many factors and processes, so many people, so many steps, machines and key personnel you are 100% dependent on – a complex picture. You need to be able to implement the solutions to solve the problems, and now we only get halfway there.

An important concern was whether the managers on the two lower levels of the hierarchy had the support of the higher managerial levels outside the division to resolve these issues.

I think that people on the top have misunderstood lean (…) It’s not enough to hire a lean expert and tell us to work with lean. You actually need resources behind the words, investments, competence, systems and a lean philosophy early on.

Discussion

The need for improved leadership competence in lean transformations is well documented (Netland et al., Citation2019). A natural response is leadership development programmes. We found that leadership programmes can indeed foster a positive development in the managers’ awareness of their individual and collective responsibilities, followed by a real change in behaviour. However, we also found that the managers’ application of new leadership competences is counteracted by the existing organisation culture, structures and systems. Hence, our findings suggest that companies should take a broad, multipronged approach to developing lean leadership.

In , we propose an integrated model for developing corporate lean leadership, in which organisations work along two dimensions. First, along a competence dimension (x-axis in ), lean training should be combined with general leadership development. Second, along an organisational dimension (y-axis in ), individual development should be supplemented by arenas for collective reflection, alignment and measures to eliminate structural and cultural barriers for lean. Our documented journey shows how the company step-by-step addressed three of the cells in the model (dark grey). Further advances would likely be made if the fourth cell (light grey) is also addressed.

Uniting the foci of HR and lean production

Our story initially showed a typical separation of leadership development (responsibility of HR) and lean training (responsibility of the lean promotion office). The extant literature also reflects a similar separation, as studies of leadership development and studies of lean training are published in different academic journals with limited cross-fertilisation. Although the role of HR in leadership development is well established (Davenport, Citation2015) and poor understanding of human aspects has been identified as a problem in lean transformations (Hopp, Citation2018), HR professionals are often absent in lean transformation processes (Thirkell & Ashman, Citation2014).

Holmemo and Ingvaldsen (Citation2016) showed how organisations tend to structure lean experts in a separate organisational unit alongside finance, IT or HR. This might be an explanation for non-coordinated activities towards the same group of managers. Our case study shows that involving corporate HR leadership-development specialists can advance the level of competence and responsibility awareness of managers in the lean journey. The same message in the same room is even better than simply gathering two silos in the same room. We therefore recommend an integrated and aligned concept for lean leadership development.

Leadership beyond individual competency

The challenges of lean leadership have recently brought attention to contextual factors (Seidel et al., Citation2019) and the need for co-creation and culturally aligned lean leadership development programmes (Ingelsson et al., Citation2020). Similarly, our model for lean leadership development highlights the organisational dimension.

Changing habitual patterns of action is a process where both action and thought are combined in a ‘reflective conversation with the situation’ (Schön, Citation1983, p. 268). As our story illustrates, the participating managers appreciated the opportunity to meet and reflect. Furthermore, they reported a higher satisfaction of being giving the extra time during the seminars to reflect on important issues concerning leadership and organisational practice, not just being taught a shared, yet rigid, curriculum. Managers often face transfer problems after attending leadership development programmes, which can be reduced if managers attend to these programmes with sub-ordinates, peers and super-ordinates (Gilpin-Jackson & Bushe, Citation2007).

It is widely recognised that becoming a lean organisation requires a shift of management paradigm, including going from individual learning to team-based and organisational learning (Mitki et al., Citation1997), even inter-organisational learning (Powell & Coughlan, Citation2020). Organisational learning is a social process with both tacit and explicit elements at multiple levels of analysis (Crossan et al., Citation1999). The presence of the common conversation, a reflective dialogue where people representing different perspectives and cultures meet in the same room to listen to themselves and others, is seen as an essential element in organisational learning (Isaacs, Citation1993). In our case, the managers urged for an arena to share issues and to coordinate their operational activities. Organisational learning systems à la Toyota are highly situational and aligned with the systems of coordination (Rother, Citation2010). Thus, we suggest that managers need shared arenas not just for temporal development programmes, but as a regular and frequent practice.

Lastly, lean should be approached as a management system, including the alignment of structures and corporate strategies across the entire management chain (Liker & Convis, Citation2012). As we experienced, despite the participation of three managerial levels, participants soon encountered obstacles beyond their field of authority. As such, we suggest that building lean leadership should include the synchronous development of managerial structures like strategy, accounting and performance management systems, as well as the physical layout and infrastructure.

Fail again, and fail better

The lean leadership journey we have documented was not, nor was it ever intended to be, completed. As Dunphy et al. (Citation1997, p. 242) concluded: ‘Corporate competencies take time to build and therefore cannot be quickly acquired’. One significant aspect of the change processes of adapting lean is patience and a mindset of long-term development. Thus, lean leadership development programmes should not be seen as single events, but rather as ongoing continuous improvement.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature on lean leadership beyond searching for the ideal lean leadership style or ideal lean managerial practices. We have suggested an integrated model for corporate lean leadership development which crosses the boundaries between conventional HR approaches to leadership development and lean training practices. Our research is limited by being based on a single Norwegian production firm, and thus generalisations based on our findings outside this context should be carefully judged. Yet, we hope to have generated actionable knowledge that might guide future interventions and theory development. We encourage further research to investigate the model with respect to its wider applicability.

The main managerial implication of our work is that organisations should move beyond sending individual managers to external courses (e.g. ‘black belt’ certification) when training them for the lean transformation. Rather, organisations should build a capacity for continuous development where leadership development is addressed holistically, that is building personal and interpersonal skills as well as improving managerial structures and practice to be aligned with lean thinking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Christian Vaage and Asle Fyllingen, who assisted us with data collection and data analysis during their master studies at NTNU.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ballé, M., Chartier, N., Coignet, P., Olivencia, S., Powell, D. J., & Reke, E. (2019). The lean sensei. Lean Enterprise Institute.

- Benders, J., van Grinsven, M., & Ingvaldsen, J. A. (2019). The persistence of management ideas: How framing keeps ‘lean’ moving. In A. Sturdy, S. Heusinkveld, T. Reay, & D. Strang (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of management ideas (pp. 271–285). Oxford University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202135

- Dahlgaard, J. J., & Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. (2006). Lean production, six sigma quality, TQM and company culture. The TQM Magazine, 18(3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780610659998

- Danese, P., Manfè, V., & Romano, P. (2018). A systematic literature review on recent lean research: State-of-the-art and future directions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 579–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12156

- Davenport, T. O. (2015). How HR plays its role in leadership development. Strategic HR Review, 14(3), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-04-2015-0033

- Dombrowski, U., & Mielke, T. (2013). Lean leadership – fundamental principles and their application. Procedia CIRP, 7, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2013.06.034

- Dunphy, D., Turner, D., & Crawford, M. (1997). Organizational learning as the creation of corporate competencies. Journal of Management Development, 16(4), 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719710164526

- Emiliani, M. L. (2003). Linking leaders’ beliefs to their behaviors and competencies. Management Decision, 41(9), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740310497430

- Gilpin-Jackson, Y., & Bushe, G. R. (2007). Leadership development training transfer: A case study of post-training determinants. Journal of Management Development, 26(10), 980–1004. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710710833423

- Grohmann, A., & Kauffeld, S. (2013). Evaluating training programs: Development and correlates of the questionnaire for professional training evaluation. International Journal of Training and Development, 17(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12005

- Holmemo, M. D.-Q., Powell, D. J., & Ingvaldsen, J. A. (2018). Making it stick on borrowed time: The role of internal consultants in public sector lean transformations. The TQM Journal, 30(3), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-09-2017-0106

- Holmemo, M. D. Q., & Ingvaldsen, J. A. (2016). Bypassing the dinosaurs? – How middle managers become the missing link in lean implementation. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 27(11-12), 1332–1345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1075876

- Hopp, W. J. (2018). Positive lean: Merging the science of efficiency with the psychology of work. International Journal of Production Research, 56(1–2), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1387301

- Ingelsson, P., Bäckström, I., & Snyder, K. (2020). Adapting a lean leadership-training program within a health care organization through cocreation. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 12(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-09-2019-0107

- Ingvaldsen, J. A., & Benders, J. (2016). Lost in translation? The role of supervisors in lean production. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 30(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002215625893

- Isaacs, W. N. (1993). Taking flight: Dialogue, collective thinking, and organizational learning. Organizational Dynamics, 22(2), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(93)90051-2

- Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D. L., Marlow, S. L., Joseph, D. L., & Salas, E. (2017). Leadership training design, delivery, and implementation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(12), 1686–1718. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000241

- Laureani, A., & Antony, J. (2017). Leadership characteristics for lean six sigma. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(3-4), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1090291

- Liker, J. K., & Convis, G. L. (2012). The Toyota way to lean leadership. McGraw-Hill.

- Mitki, Y., Shani, A. B., & Meiri, Z. (1997). Organizational learning mechanisms and continuous improvement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 10(5), 426–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819710177530

- Netland, T. H., & Powell, D. J. (Eds.), (2017). The Routledge companion to lean management. Routledge.

- Netland, T. H., Powell, D. J., & Hines, P. (2019). Demystifying lean leadership. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 11(3), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-07-2019-0076

- Poksinska, B., Swartling, D., & Drotz, E. (2013). The daily work of lean leaders – lessons from manufacturing and healthcare. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 24(7–8), 886–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.791098

- Powell, D. J., & Coughlan, P. (2020). Rethinking lean supplier development as a learning system. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(7/8), 921–943. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2019-0486

- Rother, M. (2010). Toyota kata: Managing people for continuous improvement and superior results. MacGraw Hill.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Seidel, A., Saurin, T. A., Marodin, G. A., & Ribeiro, J. L. D. (2017). Lean leadership competencies: A multi-method study. Management Decision, 55(10), 2163–2180. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2017-0045

- Seidel, A., Saurin, T. A., Tortorella, G. L., & Marodin, G. A. (2019). How can general leadership theories help to expand the knowledge of lean leadership? Production Planning & Control, 30(16), 1322–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1612112

- Shani, A. B., & Coghlan, D. (2021). Action research in business and management: A reflective review. Action Research, 19(3), 518–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319852147

- Sisson, J. A. (2019). Maturing the lean capability of front-line operations supervisors. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 10(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-02-2017-0016

- Spear, S. (2004). Learning to lead at Toyota. Harvard Business Review, 82(5), 78–86. https://hbr.org/2004/05/learning-to-lead-at-toyota

- Thirkell, E., & Ashman, I. (2014). Lean towards learning: Connecting lean thinking and human resource management in UK higher education. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(21), 2957–2977. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.948901

- Tortorella, G. L., de Castro Fettermann, D., Frank, A., & Marodin, G. (2018). Lean manufacturing implementation: Leadership styles and contextual variables. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(5), 1205–1227. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-08-2016-0453

- van Assen, M. F. (2018). Exploring the impact of higher management’s leadership styles on lean management. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(11–12), 1312–1341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2016.1254543

- van Dun, D. H., Hicks, J. N., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2017). Values and behaviors of effective lean managers: Mixed-methods exploratory research. European Management Journal, 35(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.05.001

- Womack, J. P., & Jones, D. T. (1996). Lean thinking: Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Simon & Schuster.

- Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (1990). The machine that changed the world. Simon & Schuster.