Abstract

This study investigates the reasons for Lean deployment in Micro Enterprises, the types of tools used, the challenges involved and the results obtained in Micro Enterprises in Ireland. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 22 Micro Enterprises in Ireland that have started Lean implementation over the last three years. Lean offers many benefits to Micro Enterprises similar to those observed in larger-sized enterprises, including improved productivity, quality and reduced costs. In addition, leadership support for Lean in Micro Enterprises is not a challenge for Lean deployment as many Micro Enterprises are owner-managers and thus embrace and facilitate the deployment of Lean in organisations. Furthermore, a Critical success factor for Lean in Micro Enterprises is government support and availability of Lean mentorship. Further longitudinal studies on Micro Enterprises would help study how Lean evolves in these organisations over time especially in enterprises who have employed Lean for several Leans. This is one of the first studies specific to the practical application of Lean in ME’s in Ireland and globally. For academics and practitioners and informing government funding policy, this study demonstrates that Lean can successfully be deployed in Micro Enterprises. This study demonstrates that government supports can aid Lean and enhance economic competitiveness.

Introduction

Organisations strive to improve revenue and market share in an increasingly globally competitive world. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are an important component of the economy in developed and developing countries (Müller, Citation2019). The definition of a Micro Enterprise (ME) is one which has between 1 and 10 employees and less than 2 million annual turnover (EU Commission, Citation2003). There are a quarter of a million micro-businesses in Ireland, employing almost 400,000 people (Central Statistics Office, Citation2019). Micro Enterprises rely on self-employment and operations as their only source of income, and given the level of competition from large-scale industrial outfits, most MEs are finding it difficult to compete in terms of quality or price (Prasad & Tata, Citation2009).

Lean is an effective and tested method of reducing operating costs and removing waste from operations. Lean implementation has become common in many industry sectors, including manufacturing (Antony, Setijono, et al., Citation2016), service sectors such as healthcare (Antony et al., Citation2019), financial (Leyer et al., Citation2021), public sector organisations (Antony, Rodgers, et al., Citation2016), (Juliani & de Oliveira, Citation2019), medical device (Iyede et al., Citation2018), pharmaceutical (McDermott, Antony, Sony, and Daly, Citation2022) and aerospace (Garre et al., Citation2017), industries. However, these aforementioned sectors are typically LE and SME-type organisations. Research conducted by Alkhoraif et al. (Citation2019) highlighted the lack of information and knowledge concerned with the implementation of Lean in Small-Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in comparison with implementation among Large Enterprises (LEs).

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) would not often consider Lean a competitive strategy as opposed to Lean applications in LEs, where it is integrated into strategy (Alkhoraif et al., Citation2019). Many governments have implemented government support and funding to aid Lean deployment in Micro Enterprises (Bhat et al., Citation2019). Since the early 2000s, the Irish government has supported all Irish businesses (MEs, SMEs, LEs) through the Irish Department of Enterprise. This support has been via funding, grants, training courses and access to Lean consultants to help train, mentor and implement Lean management. This initiative has been deemed to provide significant gains such as productivity up 20%, sales up 40%, delivery adherence up 43%, product and service quality up 30%, and employment up 11% across all sized enterprise sectors (Lean Business Ireland, Citation2022). However, the impact on MEs is unknown, as are the specific challenges this Micro Enterprise size faces.

Limited literature is available on Lean application in MEs globally and in Ireland (Shah & Shrivastava, Citation2013; Alkhoraif et al., Citation2019; O’Reilly et al., Citation2021). Hence as ME’s can be considered a subset of SME’s learnings from the literature on Lean deployment in SMEs are considered relevant to ME organisations.

Bhat et al. (Citation2021) have discussed Lean application in SME’s, and ME’s in India to highlight the resulting competitiveness and economic successes in order to encourage government support. O’Reilly et al.’s (Citation2021) study carried out a survey focused on Lean deployment in ME’s in Ireland; and found that Lean can be successfully applied in ME’s. However, O’Reilly et al.’s study focused more on the motivations for utilising Lean in ME’s and on the different reasons for utilising Lean tools within ME’s. Thus, this study expands a research gap and carries out a more in-depth analysis of the challenges and benefits of Lean deployment in MEs.

A qualitative study around Lean deployment within 22 MEs in Ireland who participated in the Irish government Enterprise Ireland Lean programme will be the main focus of this study. This study will provide a detailed insight on Lean deployment within Irish ME’s to ascertain the challenges and benefits encountered. The main research questions that will be addressed are:

What are the reasons for and challenges to implementing Lean in MEs?

What are the main Lean tools and techniques used by the MEs?

What benefits and results did the MEs experience after using Lean tools and techniques?

The remainder of this paper is arranged further in five sections. Section ‘Literature review’ discusses a literature review of Lean and its applications and deployment in MEs, SME’s and LEs. Section ‘Research methodology’ presents the methods approach adopted in the study. The research findings and analysis based on the interviews are presented in Section ‘Results/findings’. Finally, the discussion and interpretation of the results are examined in Section ‘Discussion’, while the conclusions are presented in Section ‘Conclusion’.

Literature review

With its origins in the manufacturing floor of the Toyota production system, Lean has become particularly essential in services and consequently gained popularity (Antony et al., Citation2020; Byrne & Womack, Citation2012). Given the origins of Lean in LE’s, subsequent deployment of Lean initiatives has tended to be in LE’s and then SME’s rather than in micro organisations (Alkhoraif et al., Citation2019). ME’s unique characteristics, available resources and capabilities differentiate them from SMEs significantly (Ravi & Ramesh, Citation2017). Voss et al. (Citation1998) stated that the owner of a Micro Enterprise can be a manager who makes strategic decisions as well as a forklift driver who loads the delivery trucks. In relation to the research question, the literature on Lean application in the ME sector is sparse and an under-explored area.

MEs are identified as owner-manager entrepreneurs (OME)-centric (Gherhes et al., Citation2016). In the ME model, the OME is frequently in charge of all the activities related to running and managing their business (O’Dwyer & Ryan, Citation2000). Thus, the OME capabilities will be important in Lean deployment. However, the literature regarding ME’s has indicated that ME’s usually hesitate to grow and are often limited in crucial professional business functions such as planning, marketing, networking, human resource management and application of information technology (Chaston, Citation2000; Greenbank, Citation2000). While there are many benefits of Lean deployment and challenges and critical success factors (CSFs) to its implementation, small organisations such as MEs need external government support with funding (Lande et al., Citation2016). Ireland and Irish businesses are well placed in that the state assists and recognises the need and competitive benefit of Lean and funds its deployment (Brennan, Citation2018; Keegan, Citation2014).

Companies that are ready for Lean and overcome challenges to the transformation will be rewarded with lower defect and failure rates and a competitive advantage in the form of greater customer satisfaction and improved operational efficiency (Duarte et al., Citation2012). Many LEs have used Lean to gain that advantage, but it is noticeable that the level of integration of Lean manufacturing in SMEs and, by inference, ME’s is quite low and that even knowledge of it is poor also (Thanki & Thakkar, Citation2019). Thanki and Thakkar (Citation2019) found that in a study of Indian-based manufacturing SME’s that despite the importance of this sector to the economy and government investment in Lean schemes, there was a very sparse uptake and lack of awareness of such initiatives and subsequently, a lack of integration of Lean in aiding to expand economic competitiveness.

In Lean application in MEs, some challenges exist that are not necessarily there in LE’s, such as processes being less defined, less permanent and difficulty collecting data (Dora et al., Citation2013). There are also misconceptions that Lean requires complicated statistical tools and techniques in a company’s processes. Yet, the simple tools of Lean, such as process mapping, cause and effect analysis, Pareto analysis, and control charts, can resolve the majority of quality problems (Reda & Dvivedi, Citation2022). Nevertheless, many challenges have been identified for smaller organisations implementing Lean management due to resource-based factors (Antony et al., Citation2018). Lack of personnel, a lack of training and cultural barriers, are deemed the biggest roadblocks to the adoption of Lean, and to initiate Lean, a company should start with proper understanding, education and attitude (Antony et al., Citation2020; Byrne et al., Citation2021; McDermott, Antony, Sony, and Healy, Citation2022b). However, these challenges are compounded in smaller organisations with fewer resources, such as ME's.

In addition, facilitating just-in-time purchasing and production were also identified as other major challenges for implementing Lean in automotive component manufacturing SMEs (Sahoo, Citation2020; Albalkhy & Sweis, Citation2021).

Several critical factors that determine the success of implementing the concept of lean manufacturing within SMEs have been identified. Leadership, management, finance, organisational culture and skills and expertise, amongst other factors, are classified as the most pertinent issues critical for the successful adoption of lean manufacturing within the SME environment (Gherhes et al., Citation2016; Bhat et al., Citation2021).

To be sustainable, Nguyen (Citation2015) argued that adopting Lean practices in SMEs should start with basic and inexpensive tools such as 5S, Kaizen and visual inspection and then later deploy more sophisticated tools such as Kanban and batch reduction. Research conducted by Hu et al. (Citation2015) found that Lean in SMEs is more applicable to internal improvement than external improvement, and the most used tools by SMEs are the simplest and cheapest ones, such as value-stream mapping, 5S, Kanban and total productive maintenance (Hu et al., Citation2015)

There are many CSFs for Lean implementation for which leadership and management involvement and commitment are critical to the success of the lean programme (Albliwi et al., Citation2014). However, while these CSFs can be common to all organisational sizes, they can vary for LE’s v’s SMEs and ME’s (Belhadi et al., Citation2019). The CSFs of Lean implementation within SMEs include organisational culture, financial position, expertise and skills, leadership style and management, employee professionalism and ability are the most important aspects for an SME to take into account when trying to implement Lean successfully (Alkhoraif et al., Citation2019). Top management commitment, understanding of the Lean methodology, tools and techniques, integration of Lean to business strategy, organisational cultural change and training and education were the key success factors (Al-Balushi et al., Citation2014; Belhadi et al., Citation2019). Organisational strategy, lack of top management support, expensive cost for Lean projects, unclear prioritisation of Lean projects and cost-effectiveness were the most important failure factors influencing Lean implementation (Iyede et al., Citation2018). Micro enterprises lack the critical resources and company culture to easily adapt to these initiatives (Inan et al., Citation2021).

A summary of the literature reviewed in relation to Lean deployment in SMEs and ME’s is summarised in .

Table 1. Literature themes related to Lean deployment in SME’s & Micro Enterprises.

Research methodology

Case settings

This study specifically looked at Irish Micro Enterprises and selected Micro Enterprises involved in the Enterprise Ireland (EI) Lean for Micro Programme. The Irish government, through EI, has been supporting Irish enterprises with Lean introduction, and in 2015 Lean for Micro Enterprises was set up as a specific initiative. This initiative aimed to introduce Micro sized Irish companies to Lean concepts. The goal was that these ME’s would gain an understanding of Lean and that the Lean tools and techniques could be of benefit for process improvements, cost reduction, productivity improvements and, ultimately, competitiveness (Enterprise Ireland, Citation2022). Since its introduction, the Lean for Micro programme run through Local Enterprise Offices (LEO’s) has had over 750 companies benefitting from its expertise and principles (Lean Business Ireland, Citation2022).

Once the ME decides to join the Lean for Micro programme, they obtain sponsored Lean training and complete an organisational-based project utilising Lean tools aided by the support of a LEO Lean consultant. In this research, the authors contacted ME organisations who had participated in the Lean for Micro programme funded by Enterprise Ireland by email to request their participation in interviews.

Sample selection

The Enterprise Ireland website has a directory or list of participating ME’s in their Lean for Micro programme, and thus a sample of these organisations was approached. As over 750 companies had participated in the EI LEO programme, the researchers selected a potential interview sample based on geographical location, type of business and LEO office involved.

All ethical considerations were considered, participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality, and informed consent was gained. Also, as the study was part of an Irish university research study, ethical approval procedures for university research studies were followed.

Qualitative Interview research was considered over a quantitative survey as interviews provide a richness of data (Opdenakker, Citation2006). In addition, interviews allow the research to explore many themes more in-depth (Saunders et al., Citation2018).

Data collection

The final interviews were conducted with 22 ME participants across Ireland in various micro-enterprise service providers and manufacturers (). Only one individual from each ME organisation was selected for interview as the authors felt that given the ‘micro’ nature of ME’s with <10 employees and often as little as one to two employees, one person was a representative sample in terms of discussing the Lean programme therein. Employees in ME’s, given the small scale of ME’s are typically cross trained in many roles and jobs, and the micro nature aids change management and improved communications and teamwork.

Table 2. Study participants by sector type with the Irish Micro Enterprise.

The interviews were scheduled via Microsoft Teams™ or Zoom™. The interviews were not scheduled to be too long as ME’s typically have less than 10 employees, are typically owner-managed and are busy due to limited resources. The questions were open-ended, allowing the participants to expand on their own views and experiences.

This interview format facilitated open discussion (Potter & Hepburn, Citation2005), allowing the participants to discuss their business context and underlying reasons that prompted them to avail of government support to introduce Lean. These provided insight into key reasons for Lean deployment, the benefits of the Lean deployment, the types of Lean tools used and the results and challenges to Lean deployment faced by these ME’s enterprises.

In terms of the motivations for implementing Lean, the benefits, the challenges involved and CSF’s for deployment, the literature informed the selection of these themes as well as a question around Lean tools utilised (Trubetskaya et al., Citation2022) was presented to the respondents to identify and discuss the motivation for the choice of the selection of lean tools used. In addition, an open interview question on the types of tools allowed respondents to list any tools also employed.

Data analysis

The interview results were recorded and, once complete, were transcribed and documented and then uploaded to ATLAS Ti9™ software using participant numbers (P numbers) to maintain anonymity. All participants publicly discussed their Lean experiences on the Lean Business Ireland website, aided by the LEO-sponsored Lean consultants. However, the researchers felt that offering anonymity to the participants might ensure more upfront, frank and reflective discussions about Lean in the interviews with the researchers. Once the researchers had completed 22 interviews, no new themes emerged, and saturation was achieved as no new themes emerged (Gupta et al., Citation2020; Saunders et al., Citation2018). Qualitative data collection usually depends on interpretation and organising and analysing themes helps aid understanding. Thus, thematic selection was used to perform qualitative analysis (Hussein et al., Citation2020). Thematic analysis of data in this research relied on systematic processes common to the grounded theory (Tuckett, Citation2005). Vaismoradi et al. (Citation2016) discussed how the key characteristics of thematic analysis are the systematic process of coding, examining of meaning and provision of a description of the social reality through the creation of theme as well as the description and interpretation of participants’ perspectives are features of all qualitative approaches.

Thus, similar themes for example benefits and challenges were identified via open coding utilising ATLAS. Ti9™ software (Cascio et al., Citation2019). Axial coding, the categorisation and sub-categorisation, and the selection of master themes were linked (Cascio et al., Citation2019; Charmaz & Belgrave, Citation2007). Finally, memoing was utilised to verify the data and help keep track of the Lean benefits, challenges, tools used and results in themes while coding with triangulation by multiple research team members (Creswell, Citation1999).

Results/findings

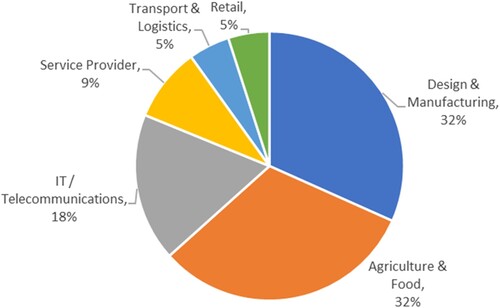

The survey was divided into two sections a demographic section and background and a section on the Lean programme deployment; the questions are outlined in the Appendix. Within the research participants, there was representation from design and manufacturing (32%), agriculture and food (32%), IT/telecommunications (18%), service providers (9%), retail (5%), and transport and logistics (5%) (). Seventy per cent of the participants were from family-run businesses, and the remaining 30% were from small-scale consultants or suppliers of goods and services. Seventy-seven per cent of micro-businesses in Ireland are family-owned (Enterprise Ireland, Citation2022). Within the Agriculture and Food section, the participants were farms, small-scale confectionery and food manufacturers. Many food-related businesses were run out of small family farms, often with just three to five employees.

The IT/Telecommunications sector contained website designers, communications providers, IT consultants and IT skills trainers. The commonality among all participants was that they were ME’s with less than 10 employees, nearly all owner run and managed businesses and were trying to increase profits and customer base. Therefore, resources for Lean deployment in this ME sector would be deemed a critical factor for deployment (Shah & Shrivastava, Citation2013).

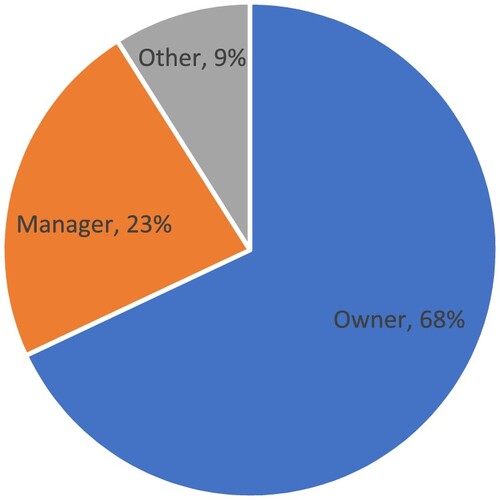

A further demographic question was asked whether the interviewee from each ME participant organisation was an owner, manager or employee (). Sixty-eight per cent of participants were owners (owner-managers) who also played a role in the day-to-day running of the ME, while 23% were managers who did not own the business but had a managerial role (often a family member). In comparison, 9% fell into the other category (non-manager, employee, family member, administrator, etc.).

Reasons for implementing a lean initiative

The ME participants were each asked, ‘What were your reasons for implementing Lean or starting training in Lean?’

Many participants commented that they did not ‘really know too much about Lean’ but understood or had ‘heard it could be helpful’ in solving their problems. A service provider ME commented, ‘before beginning the programme, we had never heard of Lean and were under the impression that it could only be applied to manufacturing businesses’(P1). However, they were unanimous (100% of interviewees) in relation to views of Lean offering the possibility to be competitive in terms of quality of products and services. A concern for ME’s was competing against larger organisations like SMEs.

Many participants mentioned that they wanted to ‘improve their stock management’ (P4) and ‘reduce congestion in the order preparation area’ (P7), and ‘make more space’(P12). While these might be reasons for LE’s and SME’s to adopt Lean also, it must be remembered that ME’s are typically family-owned and managed small businesses often run from the family home, farm, office in a house or small retail space. Thus, the environment in which they operate is ‘micro’.

External factors and pressures such as COVID-19 and Brexit were cited as reasons for looking for something ‘different’ to help the business ‘survive’. However, economic factors were cited by many. Indeed, some participants cited how both Brexit and COVID-19 happening over the same two to three year period ‘nearly closed the business’ (P7).

One participant stated, ‘we commenced our Lean journey after being hit hard by the Brexit where sales dropped by 50%’ (P17), and another participant stated, ‘our UK market disappeared overnight’ (P2). A small portion of the ME’s interviewed were exploring and had secured new markets in larger economies such as the US. New markets meant larger orders, and ‘we needed production processes that could scale up to meet demands in productivity and delivery targets’ (P12).

In terms of COVID-19, this affected the different participants differently depending on the sector involved. For example, having requirements for staff health & safety and relaying out the production and office/admin areas to aid staff working within safe distances from each other, setting up sanitising stations and ensuring PPE are available were all cited as challenges by the participants. ‘The Lean consultant helped us with layout and flow during COVID-19 to reduce chances of transmission, but the actions taken solved other problems and made us Lean by default!’ (P18).

‘Streamlining processes’ (P1, P4, P6, P11, P21) to have a positive impact right through their organisation on costs, productivity and quality was seen as the overarching reason for Lean implementation after ‘increasing competitiveness’ (almost all participants).

In summary, there were several reasons for Lean deployment in Irish ME’s. The ethos of ‘doing more with Less’ (P15) and ‘making things simpler’ (P17) reflected similar literature on Lean in ME’s in other countries. A summary of the reasons is demonstrated in .

Table 3. Key reasons for Lean initiative deployment in Irish ME’s obtained from interviews

Lean tools utilised by Irish MEs

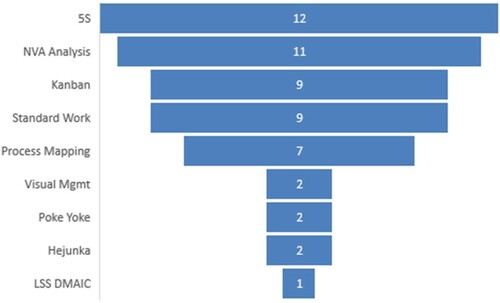

The next question asked was, ‘What Lean tools did you use and implement and why?’ This was an opened ended question to help the interviewees discuss and elaborate on the use of the particular tools and their applications in their own organisations. The tools most mentioned were non-value add waste analysis which involved identifying wastes related to Transport, Inventory, Motion, Waiting, Over-production, over-processing, and defects or TIM WOODSs. 5S, analysis, process map studies, Kanban, standardisation and Kaizen were next most mentioned. The findings in this question for ME’s correlated somewhat with Alkhoraif et al.’s (Citation2019) findings as the primary Lean tools used by ME’s in this study were simple seven waste’s analysis of value add versus non-value add wastes, standardisation, 5S and improved layouts.

The ME’s in this study chose tools focussing on efficiency, aided space utilisation, improved layout, reduced handling and stock control. Notably, as highlighted in , very straightforward and basic Lean tools were deployed. However, as these Lean deployments were new to the ME’s – more time-consuming Lean tools, e.g. Value Stream Mapping (VSM), Kaizen and Hoshin Kanri, were not utilised by all participants.

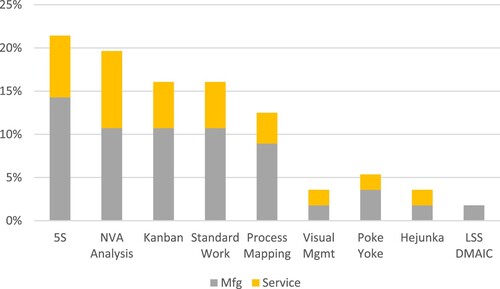

When analysing the types of Lean tools by sector the manufacturing/food sector utilised 5S, NVA analysis, Kanban’s, standardised work and Process Mapping in almost equal measures (). However, the Service sectors relied primarily on NVA analysis and 5S.

Challenges to Lean deployment within Irish MEs

The ‘micro’ characteristics of MEs in terms of the small number of employees alone are the primary difference between them and SME’s and LE’s. On the other hand, lean projects take time and require a positive organisational culture, resources, teamwork, training, leadership commitment and alignment with customers’ needs and strategy (Albliwi et al., Citation2014; Douglas et al., Citation2017).

Some scepticism about the challenges of allocating resources to work on Lean was initially mentioned by the interviewees with statements that, for example, ‘employees were under considerable pressure to manage and execute all office tasks’ (P1). However, the overall consensus from the from the non-OME participants/employees was that while they thought ‘Lean might take time’ (P4) and ‘we are busy’ (P21) but that once changes such as 5S were implemented, ‘it became easy to maintain’ (P16). Despite being an enabler and readiness factor for Lean (Albliwi et al., Citation2014), a receptive organisational culture was not cited as a major challenge or theme in the responses from ME’s. This was attributed to the fact that even though there were fewer employees and resources, there was more of a ‘we are all in it together’ (P14) mentality and attitude. In addition, employees working in close proximity meant ‘consensus’ (P10) was achieved more easily. However, ME’s are typically owner-managed; therefore, they deployed and led the Lean initiatives themselves with the support of the Enterprise Ireland consultant. ME owners/managers stated, ‘I was actively involved in the Lean deployment’ (P9), ‘I brought in the lean consultant, and I had to make this work’ (P13). ME interviewees spoke of having the autonomy to make changes with Lean; ‘I own the business, I decided I wanted to try Lean, and thus we brought it in’ (P4). One ME stated, ‘if we make mistakes, our customers suffer, they know us personally, and we know them, we do not want to damage our relationship with them’ (P20).

The researchers did not find that the ME’s cited that they encountered major obstacles and challenges to the Lean initiative. However, as the participants interviewed were owner-managers, they very much led and owned the Lean initiatives and supported them with the consultants aid-management support was not a problem.

However, as outlined in the questions on Lean tools used, the Lean tools used were not complex or time-consuming tools such as Value Stream Mapping (VSM), Kaizens, Hoshin planning or Total Preventative Maintenance (TPM). The ‘micro’ environment lent itself to be easier to implement changes and teamwork, leadership support and a positive organisation culture with a customer focus.

Results of Lean deployments

The next question was, ‘What types of results did you get with using and deploying Lean in your business?’ In this question, the researchers also asked the participants for examples of how they achieved these improvements using Lean.

In terms of the results of Lean deployment in the case study organisations, there were several benefits put forward by participant ME organisations. For example, in terms of quantitative benefits, improved productivity, reduced waste, cost reductions, improved quality and elimination of customer complaints were all listed.

These quantitative benefits included ‘15% increase in output and efficiency by eliminating waste’ (P1), and ‘eliminated manual paper based orders and implemented an online ordering system – saving on average 10,000 euro yearly in office stationary and administration salary costs’ (P3). Having implemented Lean one organisation stated, ‘we improved workplace organisation and increased available floor space by 30% in our workshop and 40% in stores and reduced rework from 20% to 5% – this saved us €42,000 annualised’ (P17). An example of some of the benefits stated is shown in .

Table 4. Sample results of Lean deployments in Irish MEs case study

However, from an organisational and qualitative point of view, several other resulting and often intangible benefits were verbalised, including ‘increased employee engagement’ (P1,P2, P11, P21), ‘improved organisational culture for problem-solving’ (P2, P6, P11, P12), ‘education in Lean and continuous improvement’ (almost all participants cited this), ‘improved team engagement’ (P1, P2, P5, P13, P19) and an ‘alignment with future strategy’ (P14, P1, P21) to name but a few benefits.

The results presented in indicated that the key results for Lean deployment in MEs were reduction of wastes, increased productivity, faster turnaround times, less administration and improved layouts both the office and production area. There are plentiful case studies available to show that Lean Deployment is predominantly introduced successfully in large corporations (Sunder M. & Mahalingam, Citation2018) and from this study it is very evident that it is and can be successful in smaller or ME companies.

However Irish government support for example was cited by the interviewees as integral to their Lean deployment.

Reflection on the involvement with the Irish government’s ‘Lean for Micro’ programme

The Irish government’s support via Enterprise Ireland’s ‘Lean for Micro’ programme had led to the initial involvement of the ME’s in this study in Lean methods deployment. Hence the researchers asked the questions, ‘Was the Enterprise Ireland support an enabler for Lean in your organisation?’ and ‘Would you have implemented Lean without it or had you planned to implement Lean?’. Most interviewees (over 70%) had stated that they had not heard of Lean prior to deployment. However, even those that had heard of Lean stated that they probably would not have implemented Lean if not approached by their Local enterprise office and asked to attend an information session. ‘The subsequent training and mentor support was invaluable’ (P13), ‘ having a business project to complete using Lean tools aided me and motivated me to deploy lean methods – but the mentor support was vital for me personally’ (P22).

Discussion

The reasons and motivations for Lean deployment in ME’s are similar to those in larger enterprises. However, the Micro nature of ME’s meant that competitiveness was deemed a key reason by 100% of the ME organisations in this study for commencing and considering looking into Lean implementation. Summarily, in one of the very few studies available on Lean adoption in ME’s in Ireland, O’Reilly et al. (Citation2021) found that the main reason for Lean adoption in Irish ME’s was the drive for competitiveness. A similar study by Kruger (Citation2018) on Lean adoption in South African ME’s also cited the drive for competitiveness as a key motivation for lean adoption.

While economic drivers have always been cited as a main driver of Lean implementation amongst other drivers (Byrne et al., Citation2021; Antony et al., Citation2007) the nature of micro organisations means day-to-day survival and competitiveness is more of a driver for Lean adoption in ME’s than elsewhere (Keegan, Citation2014; O’Reilly et al., Citation2021; Kruger, Citation2018).

Also, the fact that government-aided grant support is provided by Enterprise Ireland in its Lean for Micro programme was a key factor in the decision to implement Lean. This result echoes that of other studies (O’Reilly et al., Citation2021) where government support was deemed to aid and enable Lean deployment in ME’s.

Training, time for training and opportunities to work on projects have been much cited as CSF’s and readiness factors for Lean deployment (Belhadi et al., Citation2019; Douglas et al., Citation2017). While resource issues such as time for training and time to implement Lean changes were cited as a challenge initially by the ME’s, it was found that the changes once made and at a steady pace aided consensus, teamwork and engagement. The micro nature of the organisations facilitated an organisational culture of readiness and engagement that disseminated quickly through the ME due to its small size (Kruger, Citation2018; Bhat et al. Citation2021).

Lack of management commitment, lack of management support for training, time for training and linking Lean to strategy have been cited as one of the key CSF’s in deploying Lean in organisations (Antony et al., Citation2018; Albliwi et al., Citation2014). Due to the micro nature of the ME – all ME’s are either owner managed or have a manager directly involved in its day-to-day operations. The ME owner or managers who participated in this study made the decision to engage in the Lean programme and thus worked with the Enterprise Ireland Lean consultant to deploy Lean, motivate the team and implement Lean. Lack of management support which is cited often as a challenge and Critical failure factor (CFF) or barrier for Lean in LE’s and SME’s (Douglas et al., Citation2017; Byrne et al., Citation2021) was not a factor in the ME organisations in this study.

Within the study, the authors did not find significant differences in reasons for some MEs embracing Lean versus others. For example, those in IT services and those in Agriculture and food highlighted the same type of reasons for embracing Lean. However, there was a slight difference in the type of tools implemented. Service or office-type environments concentrated more on Lean tools with an aim to reduce administration time and invoicing (i.e. 5S and 7 wastes NVA analysis) whereas manufacturing, agriculture and food ME’s for example focused on improving flow and productivity via re-layouts and stock Kanban’s (utilising 5S, NVA, Kanban’s, Process, Mapping and standardised work in almost equal proportions).

The importance of government supports and a Lean mentor/consultant hugely aided Lean deployment in ME’s in this study and by association with the other organisations who have taken part in the Enterprise Ireland Lean for Micro Programme. Given that almost all participant ME’s stated they would not have deployed Lean if not for the government supports this support is a CSF Lean deployment within the ME environment.

In relation to the Lean tools utilised, all ME’s implemented the less time-consuming Lean tools such 5S, improved process flow, standardised work and non-value add waste analysis. Alkhoraif et al. (Citation2019) found that organisations need to tailor and align Lean tools to suit their individual structure, resources and needs and this ‘tailoring’ or ‘choosing’ of relevant tools was reflected in the findings. Bhasin (Citation2013) discussed the unpopularity of some tools among smaller enterprises compared to the popularity of those same tools among LEs. Lean in smaller organisations is mainly focused on efficiency incentives such as for example decreases in stock, storage, time (i.e. substitution time, distribution time, lead time and throughput time) and the price of products, all of which, if successful, can provide huge benefits to these organisations (Boughton & Arokiam, Citation2000).

Thus, similarly to the aforementioned studies, the ME’s in this study chose tools which focussed on efficiency, aided space utilisation, improved layout, reduced handling and stock control and could be adapted and implemented in their particular micro-environments.

In terms of benefits of Lean in the ME’s in this study, improved productivity, reduced waste, cost reductions, improved quality and reduction of customer complaints were all listed. The participant ME’s were unanimous in their support and enthusiasm for Lean. The benefits of Lean put forward by the ME’s were comparable to those benefits outlined in the literature related to SME’s and LE’s albeit on a more ‘micro’ scale (Keegan, Citation2014; O’Reilly et al., Citation2021). However, it should be re-emphasised that the ‘micro’ nature of ME’s was conducive to improved teamwork, embracing of changes, good communications and receptive organisational culture.

Theoretical implications

The paper contributes to the literature on Lean in relation to ME’s in several ways. First, it provides implications for considering CI as a viable strategy in the ME especially in light of the vast amount of literature on Lean in LE’s and SME’s. Secondly, the study demonstrated that different Lean tools were utilised or tailored depending on the organisation’s needs. This was in line with Trubetskaya et al. (Citation2022) who investigated Lean deployment in SME’s and LE’s and who emphasising how SMEs and smaller resourced organisations have to tailor the Lean tools deployed to suit resource constraints. In addition, this study enhances the body of knowledge on how leadership-led Lean projects directly benefit and enhance embracing of lean initiatives and thus their success. Finally, the study demonstrates simple Lean programmes can aid competitiveness and profitability.

Managerial implications

Practically, this study proposes recommendations and evidence that government supports can aid deployment and success of Lean programmes in ME’s and thus enhance competitiveness. Embracing of the EI LEO programmes for Lean during and in the aftermath of COVID-19 is an opportunity to rethink business strategies and plans in response to the crisis by becoming Lean. An important challenge for ME’s management is to develop processes that are efficient and value add and in line with a study by McDermott and Nelson (Citation2022) many Irish ME’s are only deploying Lean in the last two years and primarily for competitiveness. Lean can make ME’s more efficient and government-supported initiatives aid the integration of Lean into ME’s.

Conclusion

The study is one of the first in-depth qualitative studies looking at the experiences of Lean deployment in ME’s from a number of areas including benefits, challenges, CSF’s and types of tools utilised under the lens of government-sponsored and supported lean initiatives. The authors argue that this study adds to the state of the art and can be utilised as a benchmark and can inform further government policy and investment. The study further demonstrates that Lean can be applied successfully in any organisational size. ME’s have different characteristics to LE’s and SME’s and thus must tailor the deployment of Lean somewhat differently and on a smaller scale. While the benefits of Lean in ME’s are analogous to those observed in larger enterprises and in other sectors, the challenges and tools utilised can differ somewhat. Lean in ME’s tends to be introduced, led, deployed and supported by owner and managers and thus lack of management commitment is not a barrier. The micro nature of ME’s with a small number of employees aids achieving consensus and engagement more expediently and enables fast improvements. However, government support is instrumental in aiding and providing support and structure to ME organisations. In this study, the ME mentoring approach aided by an Enterprise Ireland consultant was instrumental, as it introduced Lean principles and translated it into action-based projects with clear linkages to the ME’s strategy. This reflects the management and leadership commitment and strategy alignment which have been identified as CSF’s in Lean deployment in larger organisations. In the ME’s ‘Lean for Micro’ programme, the Lean consultant ensured a very active, hands-on training, consultation and implementation of changes over a short period of time. This access to government supports and a Lean mentor provides future opportunities related to CSF’s of Lean in ME’s.

The practical implications of this research are that it provides evidence that Lean can be deployed successfully in ME’s and identifies the importance of government support and mentorship and this can aid ME’s who are considering whether to embark on a Lean journey. From a theoretical implications aspect, this is one of very few studies on Lean deployment in ME’s at this level of case study analysis and thus can be used to compare Lean in ME’s with Lean in LE’s and SME’s as well as identifying CSF’s for Lean in ME’s. The research emphasises the importance and success of government-aided support structures for Lean deployment and their role in improving economic competitiveness.

Future opportunities are to carry out further case study research on how the Lean journey has evolved in ME’s who have deployed Lean for more than two years. The expansion of this research on Lean deployment in ME’s to other countries could expand understanding of Lean in ME’s given the place of the ME in global economies. Also, the impact of Lean as an enabler for Industry 4.0 and increased digitalisation in ME’s is an opportunity for further study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Balushi, S., Sohal, A.S., Singh, P.J., Al Hajri, A., Al Farsi, Y.M., & Al Abri, R. (2014). Readiness factors for lean implementation in healthcare settings – A literature review. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 28(2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-04-2013-0083

- Albalkhy, W., & Sweis, R. (2021). Barriers to adopting lean construction in the construction industry: A literature review. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 12(2), 210–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-12-2018-0144

- Albliwi, S., Antony, J., Lim, S.A.H., & Wiele, T.V.D. (2014). Critical failure factors of lean Six Sigma: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 31(9), 1012–1030. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-09-2013-0147

- Alkhoraif, A., Rashid, H., & McLaughlin, P. (2019). Lean implementation in small and medium enterprises: Literature review. Operations Research Perspectives, 6, Article 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orp.2018.100089

- Antony, J., Downey-Ennis, K., Antony, F., & Seow, C. (2007). Can Six Sigma be the ‘cure’ for our ‘ailing’ NHS? Leadership in Health Services, 20(4), 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511870710829355.

- Antony, J., Gupta, S., Sunder M.V., & Gijo, E.V. (2018). Ten commandments of lean Six Sigma: A practitioners’ perspective. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(6), 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-07-2017-0170

- Antony, J., Psomas, E., Garza-Reyes, J.A., & Hines, P. (2020). Practical implications and future research agenda of lean manufacturing: A systematic literature review. Production Planning & Control, 0(0), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1776410

- Antony, J., Rodgers, B., & Gijo, E.V. (2016). Can lean Six Sigma make UK public sector organisations more efficient and effective? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(7), 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2016-0069

- Antony, J., Setijono, D., & Dahlgaard, J.J. (2016). Lean Six Sigma and innovation – An exploratory study among UK organisations. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 27(1–2), 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2014.959255

- Antony, J., Sunder M.V., Sreedharan, R., Chakraborty, A., & Gunasekaran, A. (2019). A systematic review of lean in healthcare: A global prospective. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 36(8), 1370–1391. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-12-2018-0346

- Belhadi, A., Touriki, F.E., & Elfezazi, S. (2019). Evaluation of critical success factors (CSFs) to lean implementation in SMEs using AHP: A case study. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 10(3), 803–829. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-12-2016-0078

- Bhasin, S. (2013). Analysis of whether lean is viewed as an ideology by British organizations. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 24(4), 536–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381311327396

- Bhat, S., Antony, J., Gijo, E.V., & Cudney, E.A. (2019). Lean Six Sigma for the healthcare sector: A multiple case study analysis from the Indian context. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 37(1), 90–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-07-2018-0193

- Bhat, S., Gijo, E.V., Rego, A.M., & Bhat, V.S. (2021). Lean Six Sigma competitiveness for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME): An action research in the Indian context. The TQM Journal, 33(2), 379–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-04-2020-0079

- Boughton, N.J., & Arokiam, I.C. (2000). The application of cellular manufacturing: A regional small to medium enterprise perspective. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 214(8), 751–754. https://doi.org/10.1243/0954405001518125

- Brennan, P. (2018). What is the experience of Irish manufacturing SMEs in overcoming the Key barriers to sustaining a lean journey beyond initial stages? Dublin Business School. https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/3540

- Byrne, A., & Womack, J.P. (2012). Lean turnaround. McGraw-Hill.

- Byrne, B., McDermott, O., & Noonan, J. (2021). Applying lean Six Sigma methodology to a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility: A case study. Processes, 9(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9030550

- Cascio, M.A., Lee, E., Vaudrin, N., & Freedman, D.A. (2019). A team-based approach to open coding: Considerations for creating intercoder consensus. Field Methods, 31(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X19838237

- Central Statistics Office. (2019). Small and medium enterprises – CSO – Central statistics office. Cso.Ie. CSO. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-bii/bii2015/sme/

- Charmaz, K., & Belgrave, L.L. (2007). Grounded theory. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology.

- Chaston, I. (2000). Organisational competence: Does networking confer advantage for high growth entrepreneurial firms? Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/14715200080001538.

- Creswell, J.W. (1999). Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In G. Cizek (Ed.), Handbook of educational policy (pp. 455–472). Elsevier.

- Dora, M., Van Goubergen, D., Kumar, M., Molnar, A., & Gellynck, X. (2013). Application of lean practices in small and medium-sized food enterprises. British Food Journal, 116(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2012-0107

- Douglas, J., Muturi, D., Douglas, A., & Ochieng, J. (2017). The role of organisational climate in readiness for change to lean Six sigma. The TQM Journal, 29(5), 666–676. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-04-2017-0046

- Duarte, B., Montgomery, D., Fowler, J., & Konopka, J. (2012). Deploying LSS in a global enterprise – Project identification. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 3(3), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/20401461211282709

- Enterprise Ireland. (2022). LeanStart – Enterprise Ireland. Enterprise Ireland.Com. https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/Productivity/Lean-Business-Offer/Lean-Start.shortcut.html

- EU Commision. (2003). Commission recommendation concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises 41.

- Garre, P., Nikhil Bharadwaj, V.V.S., Shiva Shashank, P., Harish, M., & Sai Dheeraj, M. (2017). Applying lean in aerospace manufacturing. International Conference on Advancements in Aeromechanical Materials for Manufacturing (ICAAMM-2016): Organized by MLR Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, 4(8), 8439–8446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.07.189

- Gherhes, C., Williams, N., Vorley, T., & Vasconcelos, A.C. (2016). Distinguishing micro-businesses from SMEs: A systematic review of growth constraints. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(4), 939–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2016-0075

- Greenbank, P. (2000). Micro-business start-ups: Challenging normative decision making? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 18(4), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500010333415

- Gupta, S.K., Antony, J., Lacher, F., & Douglas, J. (2020). Lean Six Sigma for reducing student dropouts in higher education – An exploratory study. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 31(1–2), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1422710

- Hu, Q., Mason, R., Williams, S.J., & Found, P. (2015). Lean implementation within SMEs: A literature review. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 26(7), 980–1012. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-02-2014-0013

- Hussein, F., Stephens, J., & Tiwari, R. (2020). Grounded theory as an approach for exploring the effect of cultural memory on psychosocial well-being in historic urban landscapes. Social Sciences, 9(12), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120219

- Inan, G.G., Gungor, Z.E., Bititci, U.S., & Halim-Lim, S.A. (2021). Operational performance improvement through continuous improvement initiatives in micro-enterprises of Turkey. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration Ahead-of-Print (Ahead-of-Print), https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-11-2020-0394

- Iyede, R., Fallon, E.F., & Donnellan, P. (2018). An exploration of the extent of lean Six Sigma implementation in the west of Ireland. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 9(3), 444–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-02-2017-0018

- Juliani, F., & de Oliveira, O.J. (2019). Synergies between critical success factors of lean Six Sigma and public values. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(15–16), 1563–1577. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1383153

- Keegan, R. (2014). Improving competitiveness using lean principles – The Irish experience. Guimaraes, Portugal. https://www.scribd.com/document/363404911/BookofProceedings-ICOPEV2014

- Kruger, D. (2018). Implementation of lean manufacturing in a small, medium and micro enterprise in South Africa: A case study, 1–10. Portland. https://doi.org/10.23919/PICMET.2018.8481937

- Lande, M., Shrivastava, R.L.., & Seth, D. (2016). Critical success factors for lean Six Sigma in SMEs (small and medium enterprises). The TQM Journal, 28(4), 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-12-2014-0107

- Lean Business Ireland. (2022). Lean for micro. Lean Business Ireland. https://www.leanbusinessireland.ie/funding-supports-overview/are-you-a-local-enterprise-office-client/lean-for-micro/

- Leyer, M., Reus, M., & Moormann, J. (2021). How satisfied are employees with lean environments? Production Planning & Control, 32(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1711981

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Sony, M., & Daly, S. (2022). Barriers and enablers for continuous improvement methodologies within the Irish pharmaceutical industry. Processes, 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10010073

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Sony, M., & Healy, T. (2022). Critical failure factors for continuous improvement methodologies in the Irish MedTech industry. The TQM Journal, 34(7), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-10-2021-0289

- McDermott, O., & Nelson, S. (2022). Readiness for industry 4.0 in west of Ireland small and medium and micro enterprises. Report. College of Science and Engineering, University of Galway. https://doi.org/10.13025/8sqs-as24.

- Müller, J.M. (2019). Business model innovation in small- and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(8), 1127–1142. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-01-2018-0008

- Nguyen, D.M. (2015). A new application model of lean management in small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Simulation Modelling, 14(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.2507/IJSIMM14(2)9.304

- O’Dwyer, M., & Ryan, E. (2000). Management development issues for owners/managers of micro-enterprises. Journal of European Industrial Training, 24(6), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590010373334

- Opdenakker, R. (2006). Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.4.175

- O’Reilly, S., Freeman, D., & Dooley, L. (2021). LSS implementation in micro enterprises: Adoption of tools to support competitiveness. In emerging trends in LSS. Purdue University Press Journal. https://doi.org/10.5703/1288284317326.

- Potter, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(4), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp045oa

- Prasad, S., & Tata, J. (2009). Micro-enterprise quality. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 26(3), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656710910936717

- Ravi, A., & Ramesh, N. (2017). Enhancing the performance of micro, small and medium sized cluster organisation through lean implementation. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 21(3), 325. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2017.10005234

- Reda, H., & Dvivedi, A. (2022). Decision-making on the selection of lean tools using fuzzy QFD and FMEA approach in the manufacturing industry. Expert Systems with Applications, 192(April), Article 116416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116416

- Sahoo, S. (2020). Assessing lean implementation and benefits within Indian automotive component manufacturing SMEs. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(3), 1042–1084. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2019-0299

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Shah, P.P., & Shrivastava, R.L. (2013). Identification of performance measures of lean Six Sigma in small- and medium-sized enterprises: A pilot study. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, 8(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSSCA.2013.059768

- Sunder M., V., & Mahalingam, S. (2018). An empirical investigation of implementing lean Six Sigma in higher education institutions. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 35(10), 2157–2180. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-05-2017-0098

- Thanki, S., & Thakkar, J.J. (2019). An investigation on lean–green performance of Indian manufacturing SMEs. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(3), 489–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-11-2018-0424

- Trubetskaya, A., Manto, D., & McDermott, O. (2022). A review of lean adoption in the Irish MedTech industry. Processes, 10(2), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10020391

- Tuckett, A.G. (2005). Applying thematic analysis theory to practice: A researcher’s experience. Contemporary Nurse, 19(1–2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.19.1-2.75

- Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., & Snelgrove, S. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis.

- Voss, C., Blackmon, K.L., Cagliano, R., Hanson, P., & Wilson, F. (1998). Made in Europe: Small companies. Business Strategy Review, 9(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8616.00078