?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose – This study aims to assess the challenges and critical success factors for agile transformation in an Irish manufacturing organisation.

Design/methodology – Mixed-methods approaches were used to collect data for this study. A quantitative survey utilising the novel Kano model and qualitative analysis using semi-structured interviews with middle and senior managers were employed as part of a case study.

Findings – Critical success factors are identified, analysed and prioritised based on the opinions of members of the organisation studied. The conclusions of this study show that factors such as people, culture, and leadership are critical to agile transformation. The most important components, in particular, are team empowerment, team flexibility, competency development, and creating and communicating a vision.

Research limitations/implications – This research focuses on a single-site case study capturing context-specific data from an organisation that recently embarked on an agile transformation.

Originality/value – This study bridges the gap between academia and practice by providing valuable insights to guide leaders in their journey to agile transformation. The findings provide new knowledge to leaders and academics concerning the most critical factors for a successful transformation.

1. Introduction

Currently, established companies are being impacted by significant societal changes and rapid technological transformations. However, many firms are struggling to adapt to these changes. With a radical change in the business environment requiring a comprehensive response, companies acknowledge the urgent need to adapt and become more agile (Khalili-Damghani et al., Citation2011). Agile organisations deploy teams, networks and ecosystems of people, some external to the organisation, who are coordinated horizontally and deliver new value to customers in an interactive fashion (Denning, Citation2016).

However, the pace of adoption of agile principles, often referred to as agile transformation, varies across different sectors (Perkin, Citation2020). Agile principles often remain poorly understood, undervalued or badly applied. Although a growing body of literature is available on the topic, an understanding of the barriers and critical success factors is still limited (Kumar et al., Citation2021). Additionally, as more established organisations experiment with this new approach, additional difficulties emerge.

Firstly, agile transformation is still a relatively new phenomenon gaining traction in traditional industries. For example, Naslund and Kale (Citation2020) found that most of the articles published using the term ‘Agile’ were published three years before their study. There is a need to better understand the concepts and theories and determine precisely how they relate to business performance and customer satisfaction (Zakrzewska et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, much prior research is related to the software development industry and its particularities (George et al., Citation2018). While empirical research has been conducted on applying agile practices outside of this domain, particularly in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing (Sindhwani et al., Citation2020; Dowlatshahi & Cao, Citation2006) -it is not always customisable and generalisable to individual organisations. This must gap must be rectified.

Secondly, there is a need to provide companies with an appropriate framework to strategically guide them to deploy practices in the industry. According to De Smet et al. (Citation2018), agile transformation is a high priority for a rapidly increasing number of organisations. Consequently, it is necessary to understand the variables involved in its implementation and management and their relationships with each other. However, Perkin (Citation2020) suggests that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Nevertheless, having mapped the landscape, it is possible to create frameworks and methodologies. However, it is imperative to investigate the enablers and inhibitors for value creation capabilities.

Third, there is a lack of management tools to guide businesses to implement agile beyond its traditional role (Ciric et al., Citation2018). In other words, there is a lack of tools to enable organisations to implement agile beyond projects and use it as a strategic tool for organisational development (Fuchs & Hess, Citation2018). Also, one study has identified more than 100 critical success factors for Agile implementation (Naslund and Kale, Citation2020). To do this, there is a need to investigate agile transformation in practice to identify context-specific requirements. However, this area is underdeveloped, and a good set of practices is still far from being agreed upon by practitioners (Kalenda et al., Citation2018). To bridge this gap, more work is needed to capture context-specific insights and analyse empirical real-world data. Thus the authors of this study are engaged with a manufacturing company to establish the most suitable agile practices to be developed according to their specific needs, so that they can improve their innovation capabilities to deliver more value to customers and stakeholders. Following the literature review the research questions will be refined with reference to the case study and presented. The goal is to contribute significantly by bridging the gap between theory and practice to aid a manufacturing company in their Agile transformation study as well as aiding other organisations in their journey to become agile.

2. Literature review

Naslund and Kale (Citation2020) state that from a transformation perspective, agile is not only suitable for projects but the entire organisation. Agile organisations are characterised as a network of small teams operating in fast learning and decision-making cycles, also known as Scrums (Sutherland, Citation2014). They are lauded for flexibility and speed (Khalid et al., Citation2020). This approach differs from traditional organisations, which are less dynamic and have siloed departments and strict hierarchy. Agile techniques improve technology projects’ performance by enhancing the stakeholders’ feedback loop and increasing organisational competitive advantage through better corporate change management, communication, and teamwork (Frankl & Paquette, Citation2016).

In contrast to agile, the traditional methodology for project management, known as Waterfall, is typically structured around plans, schedules and Gantt charts. Waterfall demands the collection of all requirements, the contractual agreement, and the definition of deliverables against a plan within the triple constraints, including time, scope and schedule through a linear set of sequential activities (Frankl & Paquette, Citation2016). Perkin (Citation2019) states that the waterfall methodology is designed to mitigate change and adaptation. Requirements are defined at the initiative's start in great detail and remain mostly unchanged throughout the project. Nerur et al. (Citation2005) compare the agile and traditional approaches and conclude that the two diverge in several aspects: management style, communication style, development life cycle, organisational culture and technology. Kotter (Citation2014) argues that to create true agility and responsiveness, businesses need to create a ‘dual operating system’ designed to sustain the rapid development of new ideas and models while still maximising the operations and efficiencies required to manage the business as usual.

A study conducted by the management consulting group KPMG (Citation2019) shows that 68% of businesses expect faster product delivery as one of the critical drivers for agility, better response to changing customer needs, and increased flexibility to adapt when facing change. In fact, companies that succeeded at achieving more significant agility benefit from faster time to market, at a rate of 60% and improved customer experience and product quality (Forbes Insights, Citation2018). Bazigos et al. (Citation2015) assert that agile organisations appear to have strong capabilities for learning, top-down innovation, capturing external ideas and knowledge sharing.

Agile transformation is gaining traction in multiple sectors. From Saab, which is producing new fighter jets to John Deere, which is developing new machines, the agile approach is accelerating growth and changing the management mindset (Rigby et al., Citation2016). Recent worldwide market research shows that out of the 274 companies surveyed, 69% of the enterprises are on the journey to implement agile for less than three years (Business Agility Institute, Citation2019). Another report suggests that 63% of the firms surveyed stated that it is a strategic priority to become an agile organisation (KMPG, Citation2019).

Despite its increased importance, the journey to becoming agile is challenging. Most traditional companies have faced significant obstacles in achieving their desired goals (Bucy et al., Citation2016). Handscomb et al. (Citation2018) have found seven common missteps in an agile transformation that companies often face. In reality, sustaining a transformation typically requires a significant mindset and behaviour change, which few leaders successfully achieve.

Another challenge faced by many firms is that the pace of change in organisations moves slower than the pace of technological development. Perkin and Abraham (Citation2017) explain that most companies are simply too slow to respond and adapt to these technological challenges. They are too slow to adapt processes, too slow to reorganise around opportunity and too slow to make decisions. In summary, organisations require a new kind of strategy, culture and skills more suited to this fast-changing world. However, it is important to note that there is a difference between doing agile and becoming agile. In a world where businesses are facing a changing environment, strength and growth come from adaptability. Successfully transitioning from a hierarchical and rigid framework to one more fluid and adaptable, that enables constant change depends mainly on the people's skills, attitudes, and behaviours (Perkin & Abraham, Citation2017). The importance of investing in culture and change on the journey to agility cannot be overstated. Agile is, above all, a mindset (Brosseau et al., Citation2019).

De Smet et al. (Citation2018) found that one of the greatest challenges to a successful agile transformation is transforming the culture and ways of working, a misalignment of ways of working includes a lack of collaboration and employees’ resistance to change. To overcome these challenges, Mohanarangam (Citation2020) suggests that training and management buy-in can support wider acceptance, as team members become more aware and knowledgeable about the new practices. As outlined in , there are a number of challenges to Agile manufacturing, some involving cultural and people-related challenges such as motivation of teams, encouraging team collaboration, encouraging problem solving, and having a conflict resolution process. Most critically having strong leadership and a strong organisational culture to promote an agile mindset, thus resulting in mitigating the aforementioned challenges, was critical. Most recently also, with the advent of agile-green and Industry 4.0 digitisation, sustainability, environmental and technological challenges to agile manufacturing have come to the fore (Ding et al., Citation2021; Hashem & Aboelmaged, Citation2013; Sindhwani et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. Challenges to Agile Manufacturing.

When reviewing 23 recent articles dealing with success factors for agile, Naslund and Kale (Citation2020) identified 103 essential success factors. The most frequently cited relate to people or culture, including factors such as top management support, engagement and motivation of employees and a cultural shift to a new mindset. Other authors reinforce these findings, as summarised in , thus showing that culture, people, leadership and organisational support-related factors are critical to a successful transformation.

Table 2. Critical success factors for agile transformation from the literature research.

To shape the culture for agile transformation, De Smet et al. (Citation2018) highlight three leadership approaches: role modelling, fostering understanding and building capabilities. Role modelling refers to the collective behaviour of leaders. Naslund and Kale (Citation2020) reflect that changing organisational culture is a long process, which requires transparency and persistence on multiple levels of the organisation, thus it takes time, is hard to maintain and often fails. Siakas and Siakas (Citation2007) contextualise and consider the agile approach to be a culture of its own, with a set of shared practices, including vision, principles, ideals, and methods, which emerge from the interaction of the team members (Chandra Misra et al., Citation2010). Leadership teams must actively engage in the cultural transformation and proactively promote, reward, mentor, coach and recognise the attributes that can support it Campanelli et al. (Citation2017). Cultural transformation has a critical influence on the dominant patterns existing in the business (Kalenda et al., Citation2018).

People and teams are at the core of agile organisations, so it is critical to understand and help teams work in new and more nimble ways. As Highsmith and Cockburn (Citation2001) assert, agile processes are designed to capitalise on each individual and each team’s unique strengths, therefore agile transformation should focus on increasing both individual competencies and collaboration levels. Training is an essential factor highlighted by Dikert et al. (Citation2016), who quotes from different studies and conclude that training on agile methods improved the chances of succeeding in the transformation.

The result of an agile transformation can be measured by how fast things are moving and how people are developed and engaged. Denning (Citation2019) emphasises that to become agile people must think differently. As coined by the author, the law of the small team breaks down big and complex plans into small batches of work, small units, short cycles, and quick feedback. This approach provides invaluable flexibility to the teams to adapt and react to the learning at each cycle. In contrast, Dikert et al. (Citation2016) alert to the fact that, in many cases, agile introduces flexibility at the team level, and warns that if the surrounding organisation is not responsive enough, it can create a conflict of dependencies that must be resolved.

Migrating from traditional to agile management attitudes can be difficult. It requires a management shift toward servant leadership and an introduction of more decentralised decision-making processes (Naslund & Kale, Citation2020). The leadership team is responsible for supporting team members to make the cultural shift from command and control to one more focused on collaboration (Measey, Citation2015). Hamman and Spayd (Citation2015) underline the need for leaders to shift from managing results to designing environments that create results. In other words, leaders must find the right balance between oversight and autonomy. Birkinshaw (Citation2018) also highlight that one of the risks of agile is that employees may become too task-oriented and results-focused.

Even after implementing agile, it is common in some organisations for management to continue to work according to the old waterfall structure and continue advocating bureaucratic policies (Dikert et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the entire organisation must embrace agile. To shape a new culture, it is crucial to be aware of the organisation's structures: hierarchy, strategy, and management support. Bazigos et al. (Citation2015) emphasise that part of what makes agile companies successful is their ability to balance speed and adaptability, on the one hand, with organisational clarity, stability, and structure, on the other. Overall, culture and structure should reinforce each other.

To conclude, organisational transformation towards agile practices and business agility is characterised by establishing a new corporate culture, ensuring people are at the heart of the transformation, shifting the leadership mindset, and providing organisational support. These critical factors work together to enable the transformation to occur successfully. In this view, success is less dependent on agile-specific aspects, such as methods and tools, and more on how organisations prepare for the change.

Within the literature it is clear that agile practice is complex and multifaceted, and not straightforward it is important to have studies that provided practical evidence of real life deployments, challenges, experiences and lessons learned. However there are gaps in the literature, in terms of the uncertain future as to how Agile will embrace green, sustainability, and increasing digitalisation. While much of the literature discussed organisational culture in terms of teamworking, agile roles, collaboration and having an agile mindset – there is no easy or uniform method to ensure this. One study identified 103 factors for agile implementation so organisations can struggle with what to prioritise from an Agile implementation point of view as they may be limited in resources. Thus the gap in the literature is summarised also as being one of a lack of practical case studies of deployments. This study fills a gap by adding to the real life state of the art a practical application study of a company deploying Agile.

Hence we outline and put forward our RQ’s having completed the literature review.

RQ1 What are the main challenges for agile implementation enterprise-wise?

RQ2 What are the critical success factors for agile transformation?

RQ3 How do the critical success factors identified in the literature apply to a manufacturing company in Ireland?

3. Methodology

The purpose of this study is to determine the main barriers and critical success factors that should be considered to ensure the successful implementation of agile practices organisation wide. To do this, a case study analysis was employed. Data were collected using both quantitative and qualitative methods from a single-site manufacturing company in Ireland. The study was developed in sequential mixed methods stages. Stage one is characterised by assessing the relevant literature available. Stage two comprises a quantitative survey of the company studied to gather relevant data, and stage three consists of semi-structured interviews with key informants. First, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify the main barriers and critical success factors to agile transformation. This analysis followed a deductive approach and provided a context to the research relative to previous studies conducted in the field of agile transformation. Saunders et al. (Citation2007) explain that this approach uses the literature to develop the theory for further testing in the case study. A single case study was deemed the best method to examine the CSF’s for Agile deployment at an individual level in a specific context of a single organisation. However a single case study can raise the question of generalisability. However a case study is that it can zone in on real-life situations and test these situations and events directly as they unfold in real time (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006). Yin (Citation2014) considers the single case study an experiment and supports the claim that they lead to generalisation of a concept at a higher level than the case study. He further elaborated that analytical generalisation is based on a) corroborating, editing, disputing or by other methods putting forward and advancing concepts related to theory that were researched in the design of the case study or b) new theoretical concepts that arose within the study completion (Yin Citation2014).

Case studies are particularly appropriate when the issue under investigation is exploratory and when there is a dearth of knowledge on the subject (Yin, Citation2011). Additionally, a single site case study is appropriate when the phenomenon under investigation is unique, critical, and revelatory (Dubé & Paré, Citation2003) as it does not separate the issue under investigation from the context. The organisation analysed is a large multisite medical device company that employs several thousand people worldwide. As this research focuses on the motivation and involvement of the entire team as a single case study in one organisation, representatives from a variety of functions in the company were included in the study. A single-case study can capture and suggest explanations for interdependencies and interactions within a particular context (Retolaza & San-Jose, Citation2017). Single-case researchers can craft the case and match it to the theoretical framework. This is carried out in order to make sense of the empirical data and develop theory, specifically in this organisation. According to Anderson et al. (Citation2020) developing theory based on single-case research provides the researcher with rich opportunities to ground the meaning of concepts in empirical observation and description. This organisation was chosen as a suitable single case study as there was an opportunity to gather information from a large team of cross functional departments within the company would aid the research objective (Retolaza & San-Jose, Citation2017).

3.1. Quantitative stage – Kano model

A survey targeting senior managers, team leaders, and team members was constructed based on the results of the literature review to assess how the population sampled perceives the critical success factors identified. The survey was targeted at members of the organisation that are familiar with new product development (NPD), new product introduction (NPI) activities and general operations. The Kano model was applied to classify the respondent’s perceptions and prioritise those based on their likelihood of agreeing or disagreeing with the factors (Gill et al., Citation2019). This advanced model is designed to prioritise features based on the degree to which they are likely to satisfy or delight stakeholders (Kano et al., Citation1984), as explained in . The model requires that each item measured contains a pair of questions. First in a functional form, which captures employees’ reactions when the requirements are fulfilled and second in a dysfunctional form, which captures reactions when the requirements are not fulfilled (Matzler et al., Citation1996). This innovative method was used over other traditional methods such as Likert scales to measure responses, as it allows features to be sorted into meaningful categories and offers a process for gaining a deep understanding of stakeholders’ requirements (Berger et al., Citation1993). In other words, it enables the separation of essential (must-have) features from peripheral, non-essential elements. The Kano evaluation table was used to analyse how different questionnaire responses interacted with each other, as shown in .

Table 3. Description of Kano categories (Coy and Cormican, Citation2014).

This approach has already been tested in manufacturing industry case studies (Lo et al., Citation2016; Gill et al., Citation2019). In the context of this research, the model is used to identify the level of satisfaction with the proposed factors, and it is expected that some specific factors will produce higher levels of satisfaction than others, allowing us to determine the relative interdependencies of the elements (). As a result, a set of recommendations can be defined to support the organisation's transformation.

Table 4. Kano evaluation table (adapted from Berger et al., Citation1993).

The survey was pre-tested following good practice and pilot-tested with six members of the organisation. Accessibility to the survey link was confirmed, the length of the questionnaire was validated, and the clarity and order of the questions were assessed (Forza, Citation2002; McDermott et al., Citation2022). The feedback was taken into consideration and minor amendments were made to improve the clarity and likelihood of completion. Before distributing the questionnaire, permission was sought by top management, including the Vice President of the organisation.

The prioritisation of factors () is calculated based on the following formula (1) as defined by Berger et al. (Citation1993):

Kano category = if (A + O + M) > (I + Q + R) then grade is Maximum (O, A, M)

(1)

(1)

The results were further analysed, evaluating their impact on respondents’ Satisfaction (Si) and Dissatisfaction (Di). According to Matzler and Hinterhuber (Citation1998), the Si and Di coefficients are calculated based on the formula (2). Ai, Oi, Mi and Ii represent the frequency of the responses in each question, i = 1, … , n, being on the total amount of questions in the questionnaire.

(2)

(2)

3.2. Qualitative stage – individual interviews

Following the analysis of the Kano survey, semi-structured interviews were conducted. This approach is often associated with an interpretive philosophy (Denzin and Lincoln, Citation2011). Six middle and higher managers from the organisation, who served as a sample for the leadership team, participated in individual semi-structured interviews.

The interview subjects were chosen based on their direct involvement in the agile implementation and their in-depth familiarity with the relevant contextual and cultural elements. provides information about the interviews.

Table 5. Interview participants’ details.

The interviews followed a semi-structured protocol. A total of 10 pre-determined open questions were used to guide each interview. The questions were focused on the challenges, critical factors and benefits expected from the agile transformation. This approach was employed as these interviews are lauded to yield quality contributions from those who participate (Creswell & Poth, Citation2016). The main findings were categorised and coded and keywords were highlighted (Cascio et al., Citation2019). The intention is to compare the interview findings with the literature review and Kano survey findings.

4. Results

4.1. Introduction

The study aimed to identify the critical success factors to support agile transformation in the context of the manufacturing company researched. The study comprised a Kano survey and interviews with middle and senior managers. It aimed to ascertain the critical factors that are essential for agile transformation. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first set of questions captured demographic characteristics such as function, role, experience, and knowledge of agile processes. The second part was related to specific agile success factors organised in four main categories namely culture, organisational support, leadership and people based on the findings from the literature review. The interviews comprised ten open questions related to the challenges, success factors and benefits of agile transformation.

4.2. Survey sample and demographics

Purposive sampling was used in this study. The survey was distributed to 65 members of the organisation, representing relevant departments and hierarchy levels, from team members to senior managers and with various levels of relevant working experience. The survey's effective response rate was 80% (52 out of 65). Of these, 88% completed all survey questions within the survey responses, whilst 12% only partially completed the survey or left some incomplete questions. According to Easterby-Smith et al. (Citation2012), 88% is more than adequate as a response rate therefore further analysis was conducted.

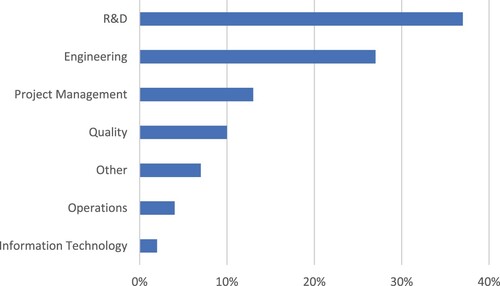

Most respondents are located in Ireland; however, the survey was also distributed to some team members situated in other sites within the organisation based in the United States, Thailand and the Philippines. The majority of the respondents’ functions were related to research & development (R&D) activities, 37%, while 27% were associated with engineering. 13% and 10% described their function as project management and quality, respectively, as seen in . The purpose of identifying the different roles across the organisation was to ensure data were captured from relevant functions involved in agile transformation.

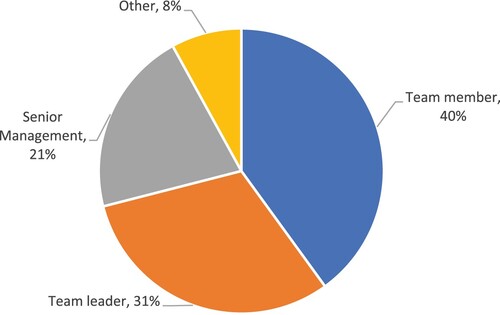

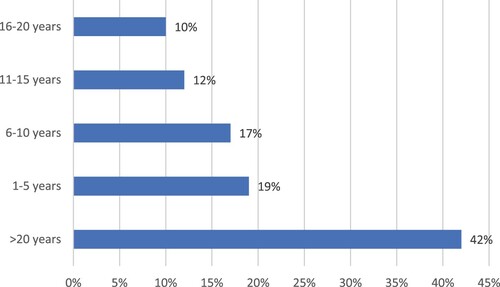

While 40% of the respondents identified themselves as team members, 31% identified as team leaders, and 21% were senior managers, as seen in . This information is important as respondents’ roles can influence their view on the contributing factors to agile. When asked about the length of relevant work experience, most (42%) had over 20 years of experience. Over half of all respondents had more than 16 years of relevant work experience see . This was important to ascertain as the level of experience could influence whether respondents were open to new ways of work or whether they were resistant to change.

42% of respondents declared that they had a moderate knowledge of agile principles and frameworks, while, equally, the same percentage stated that they had a basic knowledge of the domain. 10% of respondents had no knowledge of agile and 6% reported advanced knowledge. These results confirm that the company is still evolving their processes to increase awareness and develop agile capabilities.

4.3. Kano model survey findings

The second part of the survey captured data relating to the four critical areas that were found to influence agile transformation from the literature: culture, organisational support, leadership and people. The groups and dimensions are summarised in . Each item comprised a pair of questions, one in a positive (functional) form and another in a negative (dysfunctional) form, to check for consistency and determine the participant's perception of a particular factor. According to the Kano model the scale used is as follows ‘I Like it’, ‘I expect it’, ‘I am neutral’, ‘I can tolerate’ and ‘I dislike it’.

Table 6. Survey topics.

The survey results were captured online through SurveyMonkey® and consolidated in Excel, showing the percentage of answers per question in each of the five different possible answer alternatives and their interaction. If a respondent’s answer to a functional form of one question is ‘I expect it’, and the dysfunctional state of the question is ‘I dislike it’, that question is characterised as a ‘Must-be’ requirement, based on previously demonstrated. Following this process, results were then classified as Must-be (M), One-dimensional (O), Attractive (A), Indifferent (I), Reverse (R) and Questionable (Q), as defined previously in . As explained by Berger et al. (Citation1993), sometimes, for detailed questions, each individual will have a specific opinion, which can increase the ‘noise level’ to a point where most requirements are considered indifferent.

summarises the consolidated results following Berger’s formula (1). Therefore, for those questions where (A + O + M) > (I + Q + R), the relevant Kano category was selected from the highest frequency of the first group (Maximum of (A, O, M)). For example, question 1 is classified as Attractive, and as (A + O + M) > (I + Q + R), thus Attractive has the highest response frequency among the (A, O, M) group. The reasoning is that although 48% of people classify this factor as Indifferent, a sum of 52% of answers characterise this factor as important in one way or the other. Similarly, question 4 is classified as Indifferent as (A + O + M) ≤ (I + Q + R), as the highest frequency from the (I, Q, R) group is Indifferent.

Table 7. Summary Survey Results.

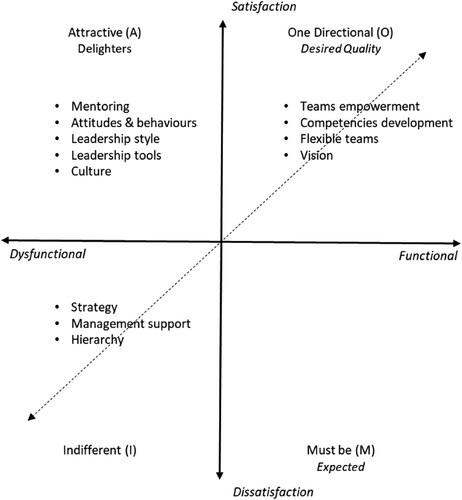

The results show that the people-related factors such as team empowerment, team flexibility and competencies development, in addition to vision, are considered One-Directional factors to the respondents. This means that the more functional the factor is, the more satisfied the employee is. On the contrary, the less functional the factor, the less satisfied the respondent is, and critically, the absence of these factors generates greater dissatisfaction.

Factors related to leadership, namely leadership tools, leadership style and mentoring, as well as culture match and attitudes and behaviours, were all classified as Attractive. These factors provide extra satisfaction when present, their presence causes a positive reaction from employees as they are usually unexpected, but when not present, they do not tend to generate dissatisfaction.

Three organisational support factors were considered Indifferent. These include strategy, management buy-in and hierarchy. This means that these factors generate neither satisfaction nor dissatisfaction if they are present or absent. According to the respondents, these factors do not make a difference or respondents do not care about them. Based on the frequency of answers and highest percentage results, the factors could be ranked from high to low priority as presented in .

Table 8. Factors ranked.

Following the formula (2) established by Matzler and Hinterhuber (Citation1998), the level of satisfaction with each item was analysed. A Si closer to 1 represents a high level of satisfaction, while a Di closer to −1 represents a high level of dissatisfaction. These coefficients reflect if the requirements are fulfilled or not. In addition to that, the greater the absolute value of Si and Di, the greater the importance of the question. According to the formula, the Si and Di from each question were calculated. summarises the results. The items highlighted in bold are the results that stand for relatively essential questions, where the level of satisfaction and dissatisfaction are greater than the average of the values. The average satisfaction is 0.466, and the average dissatisfaction is −0.393. Therefore, questions related to factors #2, #3, #7, #8, #9, #10 and #12 are considered important and should be explored further .

The 12 factors were plotted in a graph based on their results and related to Kano’s categories, following the axis of satisfaction and dissatisfaction (Y-axis) and functional and dysfunctional (X-axis), as seen in .

Table 9. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction coefficient results.

4.4. Interview findings

Twelve interviews were conducted within the case study company to obtain middle and senior management’s perspectives and insights relating to the challenges to agile, their success factors and expected benefits. All managers confirmed that they are either directly or indirectly involved in the implementation of agile. They are aware of the importance of this transformation for the organisation's long-term success. The semi-structured interviews started by introducing the topic, defining the research objectives, and reviewing some of the main findings from the Kano Survey. The open questions were applied consistently throughout all of the interviews. A total of 10 questions were posed to the interviewees relating to the challenges and success factors and the main benefits expected by the organisation associated with the agile transformation.

4.5. Main challenges to agile transformation

There is broad agreement among the management team that agile is essential to the company's future. Despite Agile’s recent introduction to the organisation in the second quarter of 2020, it is believed to support innovation and strengthen its position as the market leader. Interviewees believe that the ‘old way’ of doing things is no longer suitable given the requirements of stakeholders, including customers, society and regulatory bodies as well as the market's ever-increasing competitiveness. It is acknowledged that the company must leverage agile practices to become nimbler in product and process development. The organisation currently applies lean development principles, combined with some scrum techniques. However, all managers concur that the path to becoming more agile comes with many challenges.

When asked about the main challenges to implementing agile throughout the entire organisation, the factors highlighted included buy-in from top management. Respondents concur that agile is not fully aligned among senior managers or between senior and middle managers. Furthermore, respondents believe that a clear vision should be in place to promote the dissemination of agile initiatives as a business strategy to be executed throughout the entire organisation, rather than as a departmental process restricted to the R&D and engineering departments. The organisation's senior managers and various teams face some obstacles as a result of the current top-down strategy ().

Table 10. Challenges to agile transformation.

4.6. Critical success factors to agile transformation

The respondents concurred that senior management support is essential when evaluating the main factors that could successfully contribute to the implementation of agile throughout the entire organisation. The role of senior leaders is to remove obstacles, set the vision and influence others. Communication is also recognised as a moderator that must be improved. Other factors highlighted were training, performance systems, and the need to achieve small wins so the new practices can gain momentum ().

Table 11. The role of senior management.

The interviews focused on the seven most important factors according to the respondents’ satisfaction level in light of the Kano survey’s findings namely vision, attitudes and behaviours, leadership style, mentoring, leadership tools, team empowerment and competencies development. There was agreement on their level of importance and the need for a structured approach to their application.

It is generally acknowledged that having a clear vision is essential for implementing agile throughout the organisation. The rationale for pursuing the new practices and the expected results must be aligned and communicated to all, a roadmap must be in place to guide towards the vision, and adjustments should be made accordingly. This vision should reinforce the company’s culture. However, most managers recognised that currently, the vision is neither clear nor well communicated in the organisation ().

Table 12. The importance of vision.

It was also mentioned how important it was for team members’ attitudes and behaviours to be in line with agile. There was consensus among the interviewees that the agile mindset should drive team members’ attitudes and behaviours (). Those working with agile should expect to shift their mindset. Their attitudes should reflect an open perspective that accepts failure as a learning opportunity and is adaptable to change.

Table 13. The role of culture.

When examining leadership factors, such as leadership style, mentoring, and leadership tools, there was broad agreement on the importance of the leadership role in agile development. The interviewees also agreed that the organisation's leadership style needed to alter in order to support agile principles. More specifically, it must switch from a command and control management style to one that clearly empowers and leads the teams. Aligned with previous critical factors discussed, leaders should also be responsible for fostering the vision and setting goals and targets. Findings from the interviews also reaffirmed the need for management tools such as control systems, key performance indicators (KPIs) and balanced scorecards (BSC), which should be in place to monitor and promote improvements in the agile implementation process .

Table 14. Leadership style and roles.

Likewise, the examination of people factors, such as team empowerment and competencies development, provoked some contrasting findings. While some emphasised the importance of empowering teams, others believe that having the right people on the teams, with cross-functional experts capable of making decisions is more important than giving teams the authority to do so (). Also, they emphasised the necessity of transparent governance for decision-making, in which the responsibility of the decision-maker is clearly defined.

Table 15. The role of teams.

Additionally, the discussion on the value of developing competencies revealed a variety of viewpoints. While some support the importance of providing training to develop competencies related to agile and confirmed that the company has been providing that to a larger group, others believe that agile training serves as a mechanism to promote awareness of the methodologies (). All agreed that it is challenging to change mindsets.

Table 16. Training and its role in agile transformation: Opinions from interviewees.

4.7. Main benefits

Finally, the interviewees were asked for their opinions on the main benefits expected from the implementation of agile in the organisation. Their responses concur with the literature review findings (). Interviewees highlighted that benefits include faster product delivery, improvement in organisational learning capability and fewer resources wasted on unsuccessful projects.

Table 17. Benefits of agile transformation.

The typical product development cycle in the organisation varies from 12 to 18 months. In a rapidly changing world, this could mean that by the time the product is released, it is no longer relevant or that the competitor has already surpassed its technological features. Therefore, reducing the time to market is critical to the company's success. Agile promotes an early and continuous feedback loop with customers during product development, embedding the concept of rapid iterations and prototypes in its principles. Consequently, as highlighted by one senior manager, it allows the organisation to learn rapidly continuously and it provides the ability to adapt and react to customer needs change quickly, with less rework. Another benefit highlighted is that by constantly iterating, it is easier to allocate the right resources at the right time. Furthermore, the findings reveal that agile practices enable faster decision-making. Specifically, the interviews highlight that agile practices enable decision makers to identify whether or not a project is meeting its requirements. If it is not, it should be terminated earlier, because doing so is less expensive and enables prompt resource reallocation.

5. Discussion

Based on the major variables identified in the literature review, the study findings established the critical success factors for agile transformation.

5.1. Culture

The importance of organisational culture for a successful agile transformation is frequently emphasised in the literature (Naslund & Kale, Citation2020; Chandra Misra et al., Citation2010; Kalenda et al., Citation2018). In this research, the presence of a vision was found to be the most important cultural-related factor. The survey respondents agreed that having a clear vision for agile is essential. Additionally, during the interviews, this factor was also extensively reinforced. A clear vision must be in place to guide expectations and set the roadmap to achieve them, ultimately guiding cultural change. This is confirmed by Naslund and Kale (Citation2020), who state that creating a vision and strategy for agile transformation is critical. However, it is also important to note that insights from our interviews show that there is a concern amongst managers that a clear vision is currently not in place in the organisation. It is equally evident that the future state is not clearly defined or extensively communicated despite senior managers’ encouragement and promotion of agile. Many people considered cultural fit, attitude, and behaviour as attractive factors, which can cause delight if the organisation's culture supports agile. However, a cultural shift is yet to occur in the organisation.

Currently, only a few departments have an agile mindset and the traditional project management model is prevalent throughout the organisation. Consequently, interviewees advise that team members’ attitudes and behaviours must shift to a more open mindset, that is adaptable, optimistic and embraces changes in order to support the cultural transformation. According to Sommer (Citation2019), when agile is implemented across many departments, changes occur not just in the processes but also in the attitudes and behaviours of the people. The organisation under investigation is aiming for this kind of reform.

These findings are significant because they identify the importance of creating and communicating a vision for agile transformation. It is considered to be the most crucial factor to help a cultural shift. Without a clear context and direction, it is difficult for employees to embrace the transformation and reorient their attitudes and behaviours towards agile practices. Therefore, every effort should be made to ensure that a clear vision is in place and that it is clearly communicated. According to Dikert et al. (Citation2016), leaders must constantly remind employees of the vision.

5.2. People

People are central to successful agile transformation (Perkin, Citation2020). Team empowerment, flexibility and competency development were all classified as One-Directional in our survey. In other words, they are important since they inherently produce a high degree of satisfaction when functional. These results are in line with a growing body of literature that discusses the value of people in agile transformation. Denning (Citation2019) affirms that agile practitioners share the belief that work should be done in small, autonomous, cross-functional teams while working in short cycles and that team members receive continuous feedback from the ultimate customer or end-user.

The importance of giving teams the freedom to make decisions and function autonomously was considered to be essential by survey respondents. Results from the interviews also found that managers stressed the importance of the need for faster decision-making in the innovation process, with less bureaucracy and fewer external decision-makers.

In agile teams, once it is decided at the beginning of each short cycle what to do, the teams themselves have the autonomy to determine how the work is actually done. Perkin (Citation2020) found that there is a high correlation between the degree of empowerment present in teams and how quickly the organisation can make decisions and, therefore, how quickly it can adapt. Our findings support these expected benefits.

When asked whether training was available to develop agile competencies, over two-thirds of respondents evaluated this item as either a requirement or an essential. Additionally, this component got one of the highest satisfaction ratings on the list. A lack of training may cause team members to be unprepared for the transformation and even demotivate them from adopting agile methods (Perkin, Citation2020). There is a correlation between capabilities developed and an acceptance to adopt and apply agile techniques. Capabilities also are directly related to mindset. In other words, if employees have the competence and capabilities they have a better chance of pivoting to a new mindset.

The feedback from managers revealed that training had been provided to different team members in the organisations. They understood, nevertheless, that it must reach out to a wider audience because it is still overly focused on technical teams. Campanelli et al. (Citation2017) found that small teams with heavy workloads and organisations with limited resources may find it particularly difficult to conduct training.

Survey data suggest that respondents believe that flexible teams are beneficial. Agile organisations are built around small, adaptable units. This finding may differ from the way the company currently operates. It currently adheres to the traditional project team management model and uses large multifunctional teams, organised in a top-down hierarchical structure that adopts the Waterfall approach. A lack of flexibility is a big problem for teams. The leadership team emphasised that members of an agile team must be adaptable and have a positive outlook while dealing with change. Perkin (Citation2020) found that flexibility is related to adapting methods or processes and maximising value creation for customers.

To conclude, this research extends the evidence regarding the benefits of moving from traditional teams to small and flexible groups, empowered to self-adapt.

5.3. Leadership

Organisations that undergo an agile transformation must change their leadership approach from ‘command and control’ to ‘leadership and collaboration’. The findings from this research concur with those of other similar studies (Gandomani et al., Citation2013). The results indicate that the more functional the leadership factors are, the more satisfied the employees. Our results revealed that mentoring was the highest ranking factor in importance. However, Campanelli et al. (Citation2017) found that coaching and mentoring are one of the most challenging success factors to implement. It appears that attitude adjustment and team acceptability are related to mentoring. In other words, a positive attitude and team acceptability towards agile are essential for mentoring to succeed.

Leadership tools were also highlighted as an Attractive factor. Respondents believe that leaders should deploy the appropriate tools to support a change in organisational culture. These findings support Denning's (Citation2019) assertion that using the right leadership tools is the most effective way to alter culture.

A balanced scorecard and appropriate KPIs must be created to support and monitor the transformation, according to the interviews’ findings. It is also evident from Denning (Citation2019), who observes that one of the main mistakes made while altering the organisational culture is starting with a vision and a plan but failing to implement a management system that consolidates the behavioural changes. Responses to these findings may demand clear and structured strategic planning to consolidate the transformation.

Evidence from the survey and interviews suggests that a leadership style that encourages agile is beneficial to the organisation. It implies that a lack of encouragement could significantly constrain the teams and their ability to make decisions autonomously. Additionally, it may result in an atmosphere that discourages creativity and collaboration.

These findings concur with those of Rigby et al. (Citation2016, Citation2020), who suggest that leaders in agile organisations should lead with questions rather than orders. These findings have some managerial implications. They offer practical insights to team leaders and senior managers in the process of shifting from a traditional management approach to one that encourages agile and fosters collaboration.

5.4. Organisational support

Campanelli et al. (Citation2017) state that management support is a prerequisite for the agile transformation process. In contrast to previous studies, our findings from the survey and the interviews elicited a range of viewpoints. While survey respondents were indifferent to management support for the agile transformation, managers interviewed reinforced the importance of top management buy-in. According to the interviews, buy-in from senior managers is not evident, and differences exist between senior directors regarding the transformation approach taken. Additionally, there is evidence of a latent gap between middle and senior managers relating to the vision of the future state.

While the managers who were interviewed are more closely and actively involved in the transformation, they are more sensitive to the difficulties caused by a lack of support from top management. At the same time, the survey respondents do not have a strong view or give this factor a lot of weight.

The necessity for a clear plan is a crucial success factor, according to Naslund and Kale (Citation2020), who also emphasise the significance of strategy in transformation planning and the stages that come before the change. The traditional waterfall strategy still predominates even though the organisation has been through an agile transformation for several months. In addition, the transformation lacks a sense of urgency. All these aspects could influence the outcome. In contrast to similar studies, the survey revealed that respondents are indifferent to agile as a strategic priority. The fact that most team members are not directly participating in the transformation may be an issue. Alternatively, others believe that the transition is taking place for political reasons, which may be at odds with the organisation's strategy, rather than for a significant reason.

Additionally, hierarchy emerged as another factor that respondents are indifferent to. According to the findings, a change from traditional reporting structures to a flatter or networked approach, does not appeal to the organisations’ members. The fact that the transformation is still in its early stages may be the cause of the disparity in the findings. It may be seen as more relevant once networked teams become commonplace in the organisation.

5.5. Summary of Kano findings

As a result of the analysis of the Kano survey, four factors were considered to be the most critical: team empowerment, competencies development, team flexibility and vision, in this particular order. The more functional these factors are, the more satisfied the individuals in the company are. On the other hand, leaders must be aware that the absence of these factors can generate greater dissatisfaction. Management should therefore concentrate their efforts on these factors to optimise added value.

The findings highlight the importance of focusing on how agile teams work and the importance of changing the current teams’ structure in the organisation surveyed. These findings align with those highlighted in the literature review. The management team agrees that putting people at the centre of the transformation is crucial. To benefit from more flexible and autonomous teams, engagement and empowerment should be given top priority. his will enable faster decision-making to boost innovation.

Five factors were considered to be Delighters, meaning that they provide extra satisfaction when present. The factors are mentoring, leadership tools, attitudes and behaviours, leadership style and culture match. These factors would undoubtedly contribute to the transformation. Fulfilling these factors would lead to a greater level of satisfaction and support the teams’ engagement. There is evidence that the organisation's team members and leaders value agile. The aim is to transform the business into a better collaborative working environment, ultimately improving the company’s innovation capabilities. Moreover, three factors – hierarchy, management buy-in and strategy – were considered Indifferent, meaning they produced neither satisfaction nor dissatisfaction. Although this deviates from the findings in the literature, it exemplifies that each organisation is unique and that factors considered critical in some organisations may not be in others. It also highlights the importance of context when evaluating the critical success factors. Leaders’ feedback during the interviews stressed the importance of management buy-in. Differences in findings may be attributable to the fact that these particular managers interviewed are closer to the transformation. Therefore, they might have a different perspective from other team members. Response to these findings may demand a deeper analysis with a larger sample in the organisation. It can also be interpreted as a current evaluation, which can change over time as the other factors are reviewed and implemented further.

5.6. Contributions to theory

This study demonstrates how Kano analysis can be utilised to aid Agile deployment by focusing on the VOC. The Kano application can improve understanding on the subject and provide further insights into agile transformation in the real-world context and thus contribute of the current literature and research in the field.

5.7. Contributions to practice and policy

All organisations are difference and this study provides a customisable approach to establish Agile success factor and directions. The study demonstrates importantly that it cannot be assumed all CSF’s are equal in an organisational. Individual organisations may need to understand and customise Agile deployment to their own cultural and organisational resources and strengths. It is important that management understand the context of Agile deployments in relation to their respective organisations.

5.8. Limitations of the study and future research directions

As the study is a single case study it can be seen as not generalisable however the case study as presented was specific to this specific organisational context and environment. Also the authors focused on certain CSF’s as opposed to others within the Kano analysis. The authors would like to expand the study to investigate the status of Agile deployment within the organisation after 12–18 months to establish progress. This research is limited to a single case study in Ireland. Although valuable to this particular organisation, this study's scope generalisation is naturally limited. The study was also conducted in an organisation that has only recently embarked on the agile transformation, therefore, its applicability in other contexts may differ. Data gathered during a more extended period would have benefited the research. For future research, researchers could apply this innovative method to a more extensive sample size across several industries to compare results. Further research could involve a comparative analysis with different organisations in Ireland or globally to develop a framework for the industry.

6. Conclusion & recommendations

This research examined the challenges (RQ1) and the critical success factors of agile transformation (RQ2) and how they apply in a specific manufacturing company in Ireland (RQ3). This research provides a real-world understanding of the success factors and their relationship with each other in the manufacturing industry and may help leaders in this domain. It also has some practical implications, and leaders should not assume that all factors are equally critical. Thus, this study provides valuable and unique insights to help the management in the field while adding real-world empirical data to the body of knowledge related to agile transformation. Furthermore, this study also makes a methodological contribution. The methodology employed provides researchers and leaders with a tool that can be applied in different industries. The application would enrich the discussion on the subject, provide further insights into agile transformation in real-world contexts, and contribute further to the literature in the field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Baik, O., & Miller, J. (2015). The kanban approach, between agility and leanness: A systematic review. Empirical Software Engineering, 20(6), 1861–1897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-014-9340-x

- Anderson, R. M., Heesterbeek, H., Klinkenberg, D., & Hollingsworth, T. D. (2020). How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet, 395(10228), 931–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5

- Bazigos, M., Smet, A., & Gagnon, C. (2015). Why Agility pays. McKinsey Quarterly December 2015.

- Berger, C., Blauth, R., Boger, D., Bolster, C., Burchill, G., Du Mouchel, W., Pouliot, F., Richter, R., Rubinoff, A., Shen, D., Timko, M., & Walden, D. (1993). Kano's method for understanding customer-defined quality. Center for Quality of Management Journal, 2(4), 3–36.

- Birkinshaw, J. (2018). How is technological change affecting the nature of the corporation?. Journal of the British Academy, 6(s1), 185–214.

- Brosseau, D., Ebrahim, S., Handscomb, C., & Thaker, S. (2019). The journey to an agile organisation. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-journey-to-an-agile-organization

- Bucy, M., Finlayson, A., Kelly, G., & Moye, C. (2016). The ‘how’ of transformation. McKinsey. Retrieved August 4, 2022 from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-how-of-transformation

- Buvik, M. P., & Tkalich, A. (2021). Psychological safety in agile software development teams: Work design antecedents and performance consequences. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Campanelli, A., Bassi, D., & Parreiras, F. (2017). Agile transformation success factors: A practioner’s survey. International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering – Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 10253, pp. 364-379.

- Cao, L., Mohan, K., Ramesh, B., & Sarkar, S. (2013). Adapting funding processes for agile IT projects: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Information Systems, Taylor & Francis, 22(2), 191–205.

- Cascio, M. A., Lee, E., Vaudrin, N., & Freedman, D. A. (2019). A team-based approach to open coding: Considerations for creating intercoder consensus field methods. SAGE Publications Inc, 31(2), 116–130.

- Chandra Misra, S., Kumar, V., & Kumar, U. (2010). Identifying some critical changes required in adopting agile practices in traditional software development projects. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 27(4), 451–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656711011035147

- Ciric, D., Lalic, B., Gracanin, D., Palcic, I., & Zivlak, N. (2018). Agile project management in new product development and innovation processes: Challenges and benefits beyond software domain. 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (TEMS-ISIE) pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMS-ISIE.2018.8478461.

- Coy, R., & Cormican, K. (2014). Determinants of foreign direct investment: An analysis of Japanese investment in Ireland using the Kano model. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 11(1), 8–17.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

- Davies, R. (2009). Agile coaching. Pragmatic Bookshelf.

- Deja, M., Siemiątkowski, M. S., Vosniakos, G.-C., & Maltezos, G. (2020). Opportunities and challenges for exploiting drones in agile manufacturing systems. Procedia Manufacturing, 51, 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.10.074

- Denning, S. (2016). How to make the whole organisation ‘agile’. Strategy & leadership. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 44(4), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-04-2019-0052

- Denning, S. (2019). Lessons learned from mapping successful and unsuccessful agile transformation journeys. Strategy & Leadership, 47(4), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-04-2019-0052

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. eds. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

- Deshpande, A., Sharp, H., Barroca, L., & Gregory, P. (2016). “Remote working and collaboration in agile teams”.

- De Smet, A., Lurie, M., & St George, A. (2018). Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st-century organisations October 2018.

- Dikert, K., Paasivaara, M., & Lassenius, C. (2016). Challenges and success factors for large-scale agile transformations: A systematic literature review. Journal of Systems and Software, 119, 87–108.

- Ding, B., Hernandez, X., & Jane, N. (2021). Combining lean and agile manufacturing competitive advantages through industry 4.0 technologies: An integrative approach. PRODUCTION PLANNING & CONTROL, 34, 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1934587

- Dowlatshahi, S., & Cao, Q. (2006). The relationships among virtual enterprise, information technology, and business performance in agile manufacturing: An industry perspective. European Journal of Operational Research, 174(2), 835–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.02.074

- Dubé, L., & Paré, G. (2003). Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices, trends, and recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 597–636. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036550

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2012). Management research. SAGE.

- Eilers, K., Peters, C., & Leimeister, J. M. (2022). Why the agile mindset matters. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 179, 121650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121650

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). From Nobel Prize to project management: Getting risks right. Project Management Journal, 37(3), 5–15.

- Forbes Insights. (2018). The allusive agile enterprise: How the right leadership mindset, workforce and culture can transform your organisation. https://forbes.com/forbes-insights/

- Forza, C. (2002). Survey research in operations management: A process-based perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), 152–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210414310

- Frankl, M., & Paquette, P. (2016). Agile project management for business transformational success. Business Expert Press New York.

- Fuchs, C., & Hess, T. (2018). Becoming agile in the digital transformation: The process of a large-scale agile transformation. International Conference on Interaction Sciences.

- Gandomani, T. J., Zulzalil, H., Ghani, A. A. A., Sultan, A. B. M., & Nafchi, M. Z. (2013). Obstacles in moving to agile software development methods; at a glance. Journal of Computer Science, 9(5), 620–625. https://doi.org/10.3844/jcssp.2013.620.625

- George, J. F., Scheibe, K., Townsend, A. M., & Mennecke, B. (2018). The amorphous nature of agile: No one size fits all. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 20(2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSIT-11-2017-0118

- Gill, A., Cormican, K., & Clohessy, T. (2019). Walking the innovation tightrope: Maintaining balance with an ambidextrous organisation. International Journal of Technology Management, 79(3/4), 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2019.099611

- Gren, L., & Ralph, P. (2022). What makes effective leadership in agile software development teams?. 2022 IEEE/ACM 44th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 2402–2414.

- Gunasekaran, A., Yusuf, Y. Y., Adeleye, E. O., Papadopoulos, T., Kovvuri, D., & Geyi, D. G. (2019). Agile manufacturing: An evolutionary review of practices. International Journal of Production Research, 57(15–16), 5154–5174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1530478

- Hamman, M., & Spayd, M. (2015). The agile leader (pp. 1–16). Redmond, WA: Agile Coaching Institute.

- Handscomb, C., Jaenicke, A., Kaur, K., Vasquez-McCall, B., & Zaidi, A. (2018). How to mess up your agile transformation in seven easy (mis)steps. McKinsey Company, Organization Practice April 2018.

- Hashem, G., & Aboelmaged, M. (2013). Leagile manufacturing system adoption in an emerging economy: An examination of technological, organisational and environmental drivers. Benchmarking: An International Journal, Emerald Publishing Limited, 22, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.9

- Highsmith, J., & Cockburn, A. (2001). Agile software development: The business of innovation. Computer, 34(9), 120–127.

- Kalenda, M., Hyna, P., & Rossi, B. (2018). Scaling agile in large organisations: Practices, challenges, and success factors. Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, 30(10), e1954–e1n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/smr.1954

- Kano, N., Seraku, N., Takashi, F., & Tsuji, S. (1984). Attractive quality and must-be quality. The Journal of the Japanese Society for Quality Control, 14(2), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.20684/quality.14.2_147

- Khalid, A., Butt, S. A., Jamal, T., & Gochhait, S. (2020). “Agile scrum issues at large-scale distributed projects: Scrum project development at large”, international journal of software innovation (IJSI). IGI Global, 8(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijsi.2020040106

- Khalili-Damghani, K., Taghavifard, M., Olfat, L., & Feizi, K. (2011). A hybrid approach based on fuzzy DEA and simulation to measure the efficiency of agility in supply chain: Real case of dairy industry. International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, 6(3), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509653.2011.10671160

- Kotter, J. (2014). Accelerate building strategic agility for a faster-moving world. Harvard Business Review Press.

- KPMG. (2019). Agile Transformation – From Agile experiments to operating model transformation: How do you compare to others?. Retrieved February 10, 2021, from https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pe/pdf/Publicaciones/TL/agile-transformation.pdf

- Kropp, M., Meier, A., Mateescu, M., & Zahn, C. (2014). Teaching and learning agile collaboration. presented at the 2014 IEEE 27th conference on software engineering education and training (CSEE&T), IEEE, pp. 139–148.

- Kumar, R., Singh, K., & Jain, S. K. (2021). An empirical investigation and prioritisation of barriers toward implementation of agile manufacturing in the manufacturing industry. The TQM Journal, 33(1), 183–203. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ul.ie/10.1108/TQM-04-2020-0073

- Leybourn, E., & Elatta, S. (2019). State of Business Agility, Business Agility Institute 24.

- Lo, S. M., Shen, H. P., & Chen, J. C. (2016). An integrated approach to project management using the Kano model and QFD: An empirical case study. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(13–14), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2016.1151780

- Matzler, K., & Hinterhuber, H. H. (1998). How to make product development projects more successful by integrating kano’s model of customer satisfaction into quality function deployment. Technovation, 18(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(97)00072-2

- Matzler, K., Hinterhuber, H. H., Bailom, F., & Sauerwein, E. (1996). How to delight your customers. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 5(2), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610429610119469

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Sony, M., & Daly, S. (2022). Barriers and enablers for continuous improvement methodologies within the Irish pharmaceutical industry. Processes, 10(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10010073

- McDonald, K. J. (2015). Beyond requirements: Analysis with an agile mindset. Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Measey, P. (2015). Agile foundations BCS. The Chartered Institute for IT.

- Mohanarangam, K. (2020). Transitioning to agile-In a large organisation. IT Professional, 22(2), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITP.2019.2902345

- Naslund, D., & Kale, R. (2020). Is agile the latest management fad? A review of success factors of agile transformation. International Journal of Quality and Sevice Sciences, 12(4), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-12-2019-0142

- Nerur, S., Mahapatra, R., & Mangalaraj, G. (2005). Challenges of migrating to agile methodologies. Communications of the ACM, 48(5), 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1145/1060710.1060712

- Parizi, R. M., Gandomani, T. J., & Nafchi, M. Z. (2014). Hidden facilitators of agile transition: Agile coaches and agile champions. presented at the 2014 8th. Malaysian Software Engineering Conference (MySEC), IEEE, pp. 246–250.

- Perkin, N. (2019). Agile transformation: Structures, processes and mindsets for the digital Age. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Perkin, N. (2020). Agile transformation – structures, processes and mindsets for the digital Age. Kogan Page Limited.

- Perkin, N., & Abraham, P. (2017). Building the agile business through digital transformation. Kogan Page Limited.

- Retolaza, J. L., & San-Jose, L. (2017). Single case research methodology: A tool for moral imagination in business ethics. Management Research Review, 40(8), 890–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-07-2016-0179

- Rigby, D., Elk, S., & Berez, S. (2020). Doing agile right – transformation without chaos. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Rigby, D., Sutherland, J., & Takeuchi, H. (2016). Embracing Agile. Harvard Business Review May.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2007). Research methods. Business Students (4th ed., Vol. 6, pp. 1–268). England: Pearson Education Limited.

- Siakas, K., & Siakas, E. (2007). The agile professional culture: A source of agile quality. Software Process: Improvement and Practice, 12(6), 597–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/spip.344

- Sindhwani, R., Lata Singh, P., Kaushik, V., Sharma, S., Kumar Phanden, R., & Kumar Prajapati, D. (2020). Ranking of factors for integrated lean, green and agile manufacturing for Indian manufacturing SMEs. presented at the Advances in Intelligent Manufacturing: Select Proceedings of ICFMMP 2019, Springer, pp. 203–219.

- Singh, P. L., Sindhwani, R., Dua, N. K., Jamwal, A., Aggarwal, A., Iqbal, A., & Gautam, N. (2019). Evaluation of common barriers to the combined lean-green-agile manufacturing system by two-way assessment method. presented at the Advances in Industrial and Production Engineering: Select Proceedings of FLAME 2018, Springer, pp. 653–672.

- Sommer, A. F. (2019). Agile transformation at LEGO group. Research-Technology Management, 62(5), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2019.1638486

- Steghöfer, J.-P., Knauss, E., Alégroth, E., Hammouda, I., Burden, H., & Ericsson, M. (2016). Teaching agile-addressing the conflict between project delivery and application of agile methods. presented at the 2016 IEEE/ACM 38th International Conference on Software Engineering Companion (ICSE-C), IEEE, pp. 303–312.

- Stray, V., Tkalich, A., & Moe, N. B. (2020). The agile coach role: Coaching for agile performance impact”, ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2010.15738.

- Sutherland, J. (2014). Scrum – the art of doing twice the work in half of the time. Random House Business.

- Yin, R. K. (2011). Qualitative research from start to finish. The Guilford Press. pp. xx, 348.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case Study Research Design and Methods (5th ed., p. 282). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Younus, D. A. M., & Younis, H. (2021). Conceptual framework of agile project management, affecting project performance, key: Requirements and challenges. SSRN Scholarly Paper, Rochester, NY, 10 July.

- Zakrzewska, M., Jarosz, S., Piwowar-Sulej, K., & Sołtysik, M. (2022). Enterprise agility – its meaning, managerial expectations and barriers to implementation – a survey of three countries. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(3), 488–510. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ul.ie/10.1108/JOCM-02-2021-0061