Abstract

This paper aims at examining how the relationship between research and practice on Operational Excellence (OE) occurs. For that, a qualitative, empirical approach was conducted in which 25 experts (12 academics and 13 practitioners) from both emerging and developed economies were interviewed. Content analysis of the collected data was framed within an ecological view of the knowledge management (KM) activities. Findings indicate that, despite the growing efforts to strengthen their relationship in the past decade, there is still a gap between the knowledge of both academia and industry on OE. Nevertheless, both academics and practitioners seem to be fairly aware of the needed countermeasures to mitigate such gap in the future. Based on the commonalities found among experts’ opinions, four propositions for future theory testing and validation were formulated to stress the relationship between OE’s research and practice from the ecological perspective of KM activities. With the competitiveness increase, the search for OE is mandatory for any organization that wishes to remain active in its market. Thus, strengthening the collaboration between industry and academia may facilitate the achievement of OE, avoiding the development of isolated and/or outdated initiatives from both researchers and practitioners, being an original contribution of this study.

1. Introduction

Operational Excellence (OE) represents the consistent and reliable execution of the business strategy. The scope of OE expands on the traditional event-based model of improvement as it involves a long-term shift in the organizational culture (Asif et al., Citation2010; Carvalho et al., Citation2019). Two main aspects characterize firms in pursuit of OE: (i) systematic management of business and operational processes, and (ii) development of a culture that underpins the continuous improvement activities (Bigelow, Citation2002; Sony, Citation2019). Moreover, OE integrates operational and business performance across revenue, cost and risk (Gólcher-Barguil et al., Citation2019), fostering the organizational focus on customers’ needs and expectation (Burton & Pennotti, Citation2003; Tortorella et al., Citation2021a). OE combines a set of interlinked practices and principles that support the continuous improvement of organizations, enabling their adaptation and management in the pursuit of performance results that are sustainable in the long term (Carvalho et al., Citation2019).

Nevertheless, it is still not clear the interdependence of those practices and principles (Found et al., Citation2017), which suggests that there may be more than one approach to achieve OE (Tortorella et al., Citation2021a). This can cause confusion and misinterpretation on OE, potentially leading to a misalignment and distance between the concepts and theories discussed research-wise and the actual practice observed in organizations (Slack et al., Citation2004; Latham, Citation2008; Carvalho et al., Citation2019; Botchie et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have raised the attention to this issue in fields of knowledge intrinsic to OE, such as quality (Grant et al., Citation1994; Soltani, Citation2005; Bossert, Citation2021), supply chain (Chandra & Kumar, Citation2000; Prockl, Citation2005; Sriyakul et al., Citation2019), performance measurement (Soboh et al., Citation2009; Zanon et al., Citation2021) and sustainability (Sony, Citation2019; Mangla & Luthra, Citation2022). More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted organizations and supply chains worldwide, reducing operational efficiency and margins due to workforce shortages and supply chain instability (Deloitte, Citation2021). Hence, the implications caused by the pandemic have exposed additional gaps in OE knowledge (Tortorella et al., Citation2021b), highlighting the need for an even closer relationship between researchers and practitioners. Therefore, there is a clear gap in the literature related to studies that approach the convergences and differences of OE in research and practice. Such a scarcity of evidence motivated this study. Based on these arguments, following research question arises:

RQ. How has the relationship between research and practice in OE been perceived by both academics and practitioners?

The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it sheds light on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) associated with the existing relationship between research and practice in OE. Second, the identification of commonalities among responses of researchers and practitioners was categorized according to KM activities allowed the formulation of propositions that may support the development of a closer relationship between OE’s research and practice. Thus, those propositions establish research opportunities for future theory testing and validation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the background on the research and practice on OE, and the ecological view of KM. Section 3 describes the research method, whose results are displayed in Section 4 and further discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the article and highlights the study limitations and future research opportunities.

2. Background

2.1. Research on OE

Research on OE has been prolific, and its underpinning theories have evolved over the past decades. In the mid-1990s, Treacy and Wiersema (Citation1995) conceptualized OE as the strategy for organizations to concurrently deliver quality, price and ease of purchase, and service, at levels which competitors cannot match. Complementarily, Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park (Citation1999) provided an OE conceptualization based on ‘the 4Ps’: people, partnerships, processes and products (and services). More recently, Tortorella et al. (Citation2021a) highlighted that organizations that seek OE must adapt their processes, partnerships, products and services to lead in the current digitalization era. Regardless of the theoretical frame, attaining OE often implies the execution of broadly applicable and interdependent practices and principles, as opposed to concepts and principles specific to one domain of knowledge.

Previous research (e.g. Bigelow, Citation2002; Burton & Pennotti, Citation2003; Carvalho et al., Citation2019) suggested that OE may be successfully achieved through the adoption of some enablers. Additionally, OE has been more commonly evidenced when performance improvement was integrated across different indicators (Moktadir et al., Citation2020). In this sense, the means to OE achievement are not about coping with the existing trade-offs between performance indicators and enablers; they require a systemic approach that yields improvements in the entire organization (Soto, Citation2017). Nevertheless, Found et al. (Citation2018) and Gólcher-Barguil et al. (Citation2019) emphasized that the interrelationship among those enablers may impose nontrivial adoption challenges, and studies on this regard have not yet gotten proper attention.

consolidates some of the most recent studies on OE, i.e. works published in the last three years. Three main streams of research on OE stand out. The first stream encompassed the theoretical models that underpin OE achievement. Researchers (e.g. Edgeman, Citation2018; Found et al., Citation2018) attempted to identify the practices, elements, interactions, synergies and regularities that characterize OE achievement. The second stream approached OE from a circular economy/sustainability perspective. Studies from Sony (Citation2019) and Moktadir et al. (Citation2020), for instance, aimed at examining how OE practices can promote sustainability in industries. The third prominent and recent research stream on OE investigates the effects of digital technologies integration into existing OE strategies. Tortorella et al. (Citation2021a) sought to conceptualize OE in the current digital transformation era, while Bag et al. (Citation2020) and Dev et al. (Citation2020) combine the technological advances from Industry 4.0 with the circular economy/sustainability concepts to obtain OE. In general, OE has been directly and indirectly discussed in the literature, and researchers’ interest in this topic has been consistently growing over the past decades.

Table 1. Some recent research on OE (works published in the last three years – from 2018 on).

2.2. Practice on OE

The first step for an organization that seeks OE is to properly define the concept of OE within the context in which the organization is inserted (Soto, Citation2017). Lack of clarity about what OE really means to the organization is one of the main reasons for failures in attaining OE (Fok-Yew & Ahmad, Citation2014). The development of a measurable and actionable definition of OE is relevant to ensure organizational alignment around operational methods and practices, and results achievement (Roth et al., Citation2020). However, as management practices, technologies and customer’s requirements advance, operational expectations and standards are likely to change the perception on the attributes and performance results (Shingo, Citation2014; Sartal & Vázquez, Citation2017). Not only the attributes and results may change, but also the management terms used to refer to OE have a limited lifecycle. Hence, aspects and characteristics that once stood for OE might not indicate it today (Found et al., Citation2018).

In practical terms, several improvement approaches have been referred to as part of OE. Practices and principles derived from Lean Manufacturing (LM), Total Quality Management (TQM), Reengineering, Supply Chain Management (SCM), Six Sigma, and Statistical Process Control (SPC) have been systematically adopted to support OE achievement (Bigelow, Citation2002; Basu, Citation2004; Oakland, Citation2014; Mangla et al., Citation2020; Botchie et al., Citation2021). Such adoption has significantly favored the improvement of organizations in the last decades, being claimed as success factors for OE in organizations (Asif et al., Citation2010; Found et al., Citation2018). A recent trend in the pursuit of OE has been the integration of new digital technologies into those practices and principles as part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Tortorella et al., Citation2020a; Bittencourt et al., Citation2021).

Despite those efforts, the current state of the global economy, which has been facing extremely high levels of uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic, has made manufacturing leaders resize their firms and revise their OE roadmap to meet realistic levels of demand and resources (Fettermann, Citation2021). According to the annual global CEO survey reported by PwC (Citation2020) OE strategies must focus on creating agility, which is likely to allow manufacturers to pivot and adapt to the constantly changing conditions on the ground. This can be attained through (i) strengthening technological capabilities across functions, (ii) reorganizing global supply chains and (iii) building a workforce with the Fourth Industrial Revolution skill sets. In the same vein, after surveying more than 500 US executives and senior leaders, Deloitte (Citation2021) indicated that the OE achievement in the upcoming years will rely on five trends: (i) preparation for the future of work and talent scarcity, (ii) re-design supply chains for advantages beyond the next disruption, (iii) accelerated digital technology adoption, (iv) new preparedness levels to rising cyberattacks and (v) investments to advance in sustainability.

At a first glance, the trends reported for the manufacturing industry and the research topics approached in the recent literature seem to be fairly aligned. However, the participation of manufacturing industry (percentage of gross domestic product) in most economies has been consistently decreasing over the past years (The World Bank, Citation2021). This suggests that, despite the increasing research efforts, the outcomes and recommendations for OE achievement are not closely linked with the actual results from manufacturing industry. Further, data from Dieppe’s (Citation2021) report indicate that productivity growth in both emerging and developed economies has slowed sharply since 2007, conflicting with the advances observed in OE theory in the same period. Therefore, although many OE concepts have firstly emerged from practical application and observation in the manufacturing industry, there seems to be a mismatch between what has been researched in academia and practiced in most organizations.

2.3. Ecological view of knowledge

Organizational knowledge processes encompass the creation, distribution, use and exchange of knowledge for purposes of value creation. These processes are best understood with the ecology and ecosystem metaphors (Shrivastava, Citation1983; Lista & Tortorella, Citation2022; Tortorella et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). The concept of a knowledge ecosystem is a stream of KM which fosters the dynamic evolution of knowledge interactions between entities to improve decision-making and innovation based on improved evolutionary networks of collaboration (Bray, Citation2007; Durst & Zieba, Citation2019). Knowledge ecosystems claim that knowledge strategies must support more enabling self-organization in response to changing environments (Yang et al., Citation2009; Järvi et al., Citation2018). The combination between knowledge and faced problems determines the degree of ‘fitness’ of a knowledge ecosystem (Chen et al., Citation2010; Farooq, Citation2018).

To comprehend knowledge ecology from a productive operation perspective, it is important to approach the knowledge ecosystem that lies at its core. Knowledge ecosystems have inputs, throughputs and outputs operating in an open exchange relationship with their environments (Cheng & Leong, Citation2017). In this scenario, several layers and levels of systems might be combined to compose an entire ecosystem (Durst & Zieba, Citation2019). These systems comprise interlinked knowledge resources, databases, human experts and artificial knowledge agents that collectively provide knowledge on the performance of organizational activities (Shrivastava, Citation1998; Järvi et al., Citation2018; Farooq, Citation2018).

The ecological perspective of KM as an organic and interactive environment has been widely investigated in the literature (Järvi et al., Citation2018; Farooq, Citation2018; Durst & Zieba, Citation2019). For instance, Shrivastava (Citation1998) stated that the key elements of a knowledge ecosystem include aspects related to technology, learning community and organizational dimensions. Malhotra (Citation2002) provided a knowledge ecology that considers not only the human but also their actions and performance. Chen et al. (Citation2010) suggested an ecological model for KM that comprises knowledge distribution, interaction, competition and evolution. Chang and Tan (Citation2013) proposed the utilization of practice and leverage of organizational knowledge as ecosystems that might be improved via collaborative learning. Cheng and Leong (Citation2017) assessed the KM activities (i.e. creation, retrieval, transfer and application) from the bottom up rather than from the top down within an ecological environment.

3. Method

Due to the exploratory and descriptive nature of our research question, a qualitative study was carried out (Voss et al., Citation2002; Barratt et al., Citation2011), in which a priori theorization was used to frame the research design (Ketokivi & Choi, Citation2014). This approach provided a more in-depth comprehension about the issues that distance research and practice in OE, generating new insightful findings to the body of knowledge. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that those findings cannot be statistically generalized.

The methodological design comprised four main steps: (i) determination of the ecological environment, (ii) definition of selection criteria, (iii) interviews with experts; and (iv) analysis of content and formulation of propositions. These steps are detailed next.

3.1. Determination of the ecological environment

According to Cheng and Leong’s (Citation2017) suggestions, the determination and understanding of the ecological environment is a step that needs to be firstly addressed to properly analyze KM. This step involves the selection of disciplines being examined, the basic operations within each discipline, the power relations between them, and how they connect to each other. Due to the specificities of the contextual environment and different natures of issues (Järvi et al., Citation2018; Farooq, Citation2018; Tortorella et al., Citation2022a), there is no formal procedure for the preliminary step. Generally, the most common approaches comprise literature review and a pilot study with associated subjects. The ecological environment was determined based on the lore of knowledge of the correlated disciplines and their contexts of application.

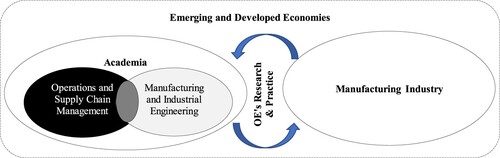

In this study, the ecological environment involved the interrelationship of knowledge on OE development between academia and industry on OE development. More specifically, in academia, two main disciplines were selected: (i) operations and supply chain management, and (ii) manufacturing and industrial engineering. Over the past decades, these two disciplines have been the main vehicles for conducting studies in OE, as evidenced in studies from Bigelow (Citation2002), Found et al. (Citation2018) and Tortorella et al. (Citation2021a). In terms of industry, we focused on manufacturing companies, since many of the widely deemed OE management approaches, such as LM (Womack et al., Citation2007; Sawhney et al., Citation2020), Six Sigma (Montgomery & Woodall, Citation2008; McDermott et al., Citation2021) and, more recently, Industry 4.0 (Lasi et al., Citation2014; Lista & Tortorella, Citation2022), have been originally conceived in such environment. As manufacturers have traditionally led the development of cutting-edge practices and approaches that were later expanded to other industry sectors (Chiarini & Kumar, Citation2020), it seems reasonable to obtain the perceptions of senior managers from this context when discussing OE achievement. Overall, knowledge on OE can move from either academia to industry, or vice-versa, which justifies the selected ecological environment for investigation. The conceptual model of the ecological environment examined in this research is displayed in .

3.2. Definition of selection criteria

To select the interviewees, a few criteria were determined. First, because it was wanted to confront theoretical and practical perceptions on OE, both academics who have investigated OE for at least 10 years, and experienced practitioners (i.e. minimum of 15 years of experience) who have played key leadership roles (e.g. manager or director) in large-sized companies (i.e. > 500 employees) were invited. As suggested by Tortorella et al. (Citation2021a), combining different perspectives would allow a broader understanding of the investigated topic. Second, all involved practitioners should work in manufacturers that have consistently implemented OE practices, techniques, or approaches, such as LM, Six Sigma, TQM, etc. Third, since it was aimed to conceive a generalizable understanding of how OE is perceived in both research and practice, academics and practitioners from different nationalities were sought. As national culture and socioeconomic context may imply different challenges to research and practice in OE (Sriyakul et al., Citation2019; Henríquez-Machado et al., Citation2021), the expectation was to identify certain variations in interviewees’ perceptions.

To identify experts who would meet all the selection criteria, it was relied on the international network of the authors who performed this study. This experienced group of authors has been collaborating and performing industry-oriented research over the last decades, which allowed the development of an extensive network with manufacturers and researchers located in several countries. Each author assessed their network and screened potential interviewees that met all the aforementioned requisites. An invitation email with a consent form and a plain language statement, which informed that participation was voluntary and the information provided would be kept anonymous, was sent to the potential interviewees. In total, 25 academics and 34 practitioners were initially contacted; of those, 12 and 13, respectively, agreed to join the study and participate in the interviews.

The profiles of the 25 interviewees are displayed in . Experts presented balanced characteristics in terms of experience, socioeconomic context (emerging and developed economies), backgrounds and roles, which met the defined selection criteria and ensured the quality and legitimacy of their responses (Shetty, Citation2020). Previous qualitative studies (e.g. Guest et al., Citation2006; Fugard & Potts, Citation2015; Braun & Clarke, Citation2016; Boddy, Citation2016) have suggested a sample size of at least twelve interviewees to achieve data saturation among a relatively homogeneous population. Hence, the sample size was large enough to explain the phenomenon of interest and address the investigated research question, avoiding repetitive data, and attaining theoretical saturation (Vasileiou et al., Citation2018).

Table 2. Profiles of the interviewed experts.

3.3. Interviews with experts

Data was collected through online interviews between September and November 2021. The data collection method was based on theoretical sampling. Following Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008, p. 143), its purpose is to ‘collect data from places, people, and events that will maximize opportunities to develop concepts in terms of their properties and dimensions, uncover variations, and identify relationship between the concepts’. The distinction between theoretical sampling and conventional methods of sampling is that the former is responsive to the data rather than established before the research begins. In other words, it was about discovering important concepts and their characteristics and dimensions.

Individual interviews followed a semi-structured protocol with open-ended questions (see Appendix). Questions were divided into four main parts. The initial part asked about the professional background of interviewees. The second part had questions on their understanding of OE in manufacturing environments. Although the discussion on the OE concept was not the focus of this research, responses to this part served as a preliminary check in which it was examined whether interviewees had a homogeneous definition of OE, regardless of their background. The third part comprised questions about how they perceive the existing relationship between OE’s research and practice, indicating its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

All interviews were audio-recorded and followed the same semi-structured protocol, lasting from 30 to 60 min. It was not introduced any ideas from previous interviews into subsequent ones, as suggested by Guest et al. (Citation2017). Each interview was attended by at least two of the authors, so that our ability to handle contextual information confidently was enhanced (Dubé & Paré, Citation2003).

3.4. Analysis of content and formulation of propositions

To allow the development of a chain of evidence that would support the formulation of propositions for future theory testing (Carter et al., Citation2014), a content analysis of information gathered in interviews was performed. This content analysis occurred during the second half of November 2021. Interview coding, cross-interview analysis and fact checking to interpret data were performed. Idiosyncratic information was neglected to ensure the focus on the prevailing patterns among interviewees. Data from interviews were transcribed and subsequently examined and discussed, yielding summaries that were then merged after consensus was reached (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994; Tortorella et al., Citation2020a; Alemsan et al., Citation2022). Due to the ease of organizing, words and short phrases were utilized as labels to code the qualitative data and identify different themes and their relationship (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). These codes were divided into groups based on how different and related they were. This generated a narrative made up of the transcriptions plus ideas and insights, helping to organize findings into meaningful information blocks.

Furthermore, to minimize the potential bias existing in interviewees’ opinions, responses were cross compared based on their respective socioeconomic contexts (emerging or developed economy) and background (academic or practitioner). Arguments that were equally mentioned by interviewees from the same group were regarded, and it was avoided the ones that were loosely cited within each group. Two of the authors individually analyzed the transcripts from the interviews. Whenever they did not agree on a certain aspect, a third author was involved to untie the decision (Tortorella et al., Citation2020b), so that the reliability was increased and biased findings minimized. Information on the relationship between research and practice on OE was initially grouped following the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) framework (Humphrey, Citation2005). This information was also distinguished between experts’ background and socioeconomic context.

Insights derived from this categorization were then checked for commonalities among experts. Items that were mentioned by experts with different backgrounds or located in different socioeconomic contexts were consolidated and classified according to the main KM activities (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001; Lista & Tortorella, Citation2022; Tortorella et al., Citation2022b): (i) knowledge creation, (ii) knowledge retrieval, (iii) knowledge transfer and (iv) knowledge application. The identification of commonalities among all information sources was categorized in three classes: ‘not explicitly referred to’, ‘briefly referred to’ and ‘emphatically referred to’. To support this classification, previously mentioned narratives (e.g. details in examples provided, arguments used by interviewees and observed characteristics) were revisited to determine data documentation, including all comments, ideas and insights (Narasimhan, Citation2014). It is worth mentioning that we only considered items that were either briefly or emphatically mentioned by at least two different groups of experts, i.e. academics from emerging economies (AEE), practitioners from emerging economies (PEE), academics from developed economies (ADE) and practitioners from developed economies (PDE).

Based on this emphasis assessment, general propositions were formulated to stress the relationship between OE’s research and practice from the ecological perspective of KM activities.

4. Results

With respect to interviewees’ understanding about OE definition, responses presented a reasonable level of similarity. Both academics and practitioners acknowledged the fact that OE involves more than just a set of practices, principles and techniques. They emphasized the systematic and continuous search for improvement at all levels as part of the culture of an organization that pursues OE. In fact, some practitioners, such as P1, P4 and P11, suggested that OE may be conceptualized more as a state to be pursued than a state to be, since the search for excellence is incessant. Moreover, some academics highlighted that a true OE should expand beyond the organizational limits towards the entire supply chain. As stated by A8:

Companies are not isolated islands; the effectiveness of their management approaches and success of their operational performance are influenced by factors that go beyond their walls. The pursue for excellence must necessarily consider the supply chain development as whole.

Overall, the provided responses for OE’s definition were consistent among interviewees and presented the expected level of conceptual depth. These indicated homogeneity in experts’ understanding, meeting the requirements to proceed with the next questions of the interview.

In terms of the experts’ perceptions about the relationship between OE’s research and practice, shows some key comments categorized according to the SWOT framework. First, concerning the strengths of such relationship, academics and practitioners from both emerging and developed economies recognized that, although far from the ideal situation, there has been a growing tendency to value the interaction between academia and industry. In academia, some key performance indicators have been changing to consider the interaction between research and practice. These initiatives intend to encourage OE researchers to work closely with industry so that practical implications become just as important as theoretical contributions. In industry, some manufacturers have established formal continuous improvement departments or teams, which have been displaying a greater propensity to engage with academics. Such engagement has been particularly mentioned when coping with higher complexity issues in the industry. Particularly mentioned by academics from developed economies, the existence of structured research centers in OE funded by a set of companies seems to be a gateway to strengthen the collaboration industry. This was not observed in the comments of academics from emerging economies.

Table 3. Interviewees’ perceptions on the relationship between OE’s research and practice.

With regards to the current weaknesses of the relationship between OE’s research and practice, poor communication appears to be a prominent issue. Academics (e.g. A3 and A9) argued that the findings from most research in OE are shared through the publication of journal articles, which are something that are not usually read by practitioners. In addition, confidentiality agreements impair greater transparency in the communication and dissemination of learning. On the other hand, practitioners commented that they are not often aware of what researchers have been developing, undermining the incorporation of the knowledge in OE raised from research. Further, they mentioned that there seems to be still a delay between the research and practice in OE; what academics are currently studying may not be today’s focus of practitioners. Another comment that came up consistently from both practitioners and academics was related to the lack of empathy between them. While some researchers have little experience in a manufacturing shopfloor, practitioners appear to be oblivious to research in OE. Overall, all these weaknesses seem to be somewhat associated with poor communication between both.

In terms of opportunities, academics (e.g. A1 and A5) highlighted the need to merge the short-term needs and goals from manufacturers with the long-term perspective from research in OE. This seems to converge to practitioners’ view, as some of them mentioned that the manufacturing shopfloor must be seen as a place to run experiments that can embrace both OE’s research and practice interests. Additionally, practitioners (e.g. P8, P12 and P13) appear to recognize that, as competitiveness increases and profit margins reduce, they must foster a collaborative relationship with researchers so that they can collaboratively develop and incorporate cutting-edge OE techniques and methods into their processes, products and services. At the same time, academics realized that industry-oriented research has been more appealing for publication in high-impact journals.

Finally, regarding threats, one of the issues raised by practitioners is related to academia’s responsiveness. According to P7 and P10, as part of the OE strategies, the industry must provide solutions in a short time slot so that customers are satisfied and competitors overcome. In opposition, academics are used to having longer times to develop countermeasures, which might become a reason for procrastination. On the other hand, academics (e.g. A2, A3 and A4) have emphasized that, because practitioners are usually consumed by their daily routine activities, they tend to struggle to anticipate problems. This may generate a reactive behavior that undermines the development of consistent long-term solutions. In general, both academics and practitioners argued that the lack of a common ground for discussing OE advances may be a critical threat, since it can distance them even further.

5. Discussion

summarizes the commonalities among experts (academics and practitioners from both emerging and developed economies), categorizing according to the main KM activities. From a knowledge creation perspective, no characteristic in the SWOT framework was either briefly or emphatically mentioned by all groups of experts. Both ADE and PDE recognized the growing incentives for more industry-oriented research on OE. Although this strength may be more prominent in developed economies’ context, a similar phenomenon has been observed in emerging economies too. For instance, data from the World Bank (Citation2019) indicated that China’s spending on research and development has gone from 0.5% of its gross domestic product to 2.2% in less than 20 years, and its body of researchers and annual number of patents is currently higher than that of the USA. Such trend has also been argued by Anand et al. (Citation2021). With respect to the weaknesses in knowledge creation, AEE and PEE emphasized the lack or little awareness of the current OE’s research and practice activities. This may aggravate the disconnection between both worlds (research and practice), yielding narrow approaches to OE. Nevertheless, experts’ opinions converged more frequently when considering opportunities and threats. Particularly for opportunities, PEE, ADE and PDE briefly or emphatically acknowledged that the novel digitalization trends implied by I4.0 have been encouraging a closer collaboration between industry and academia. This outcome is somewhat aligned with findings from Erro-Garcés (Citation2019), which highlighted the need to combine academic and practitioner efforts to better understand the implications of I4.0 to OE. Although I4.0 is a widely discussed topic, both practitioners and researchers still struggle to grasp its concepts (Fettermann et al., Citation2018), raising opportunities for the development of synergistic initiatives towards knowledge creation. Regarding threats, AEE, ADE and PDE claimed that the differences between the short-term focus from practitioners and academics’ long-term orientation could undermine this relationship. Slack et al. (Citation2004) and PwC (Citation2020) raised a similar concern by indicating that the working horizons from industry and academia may differ, leading to conflicting ambitions. Against this backdrop, the following proposition on OE knowledge creation was formulated:

Table 4. Commonalities in the relationship between OE’s research and practice according to KM activities.

Proposition 1

The OE knowledge creation is likely to be strengthened by the increasing incentives for industry-oriented research, weakened by the little awareness on current research and practice activities, enhanced by the digital transformation trends, and threatened by the differences between practitioners’ short- and researchers’ long-term orientation.

From the knowledge retrieval standpoint, both ADE and PDE agreed that manufacturers have been increasingly recruiting researchers (former PhD candidates) to be part of their workforce. In fact, McCarthy and Wienk (Citation2019) reported that universities are no longer the main career option for researchers in Australia. Complementarily, Ori (Citation2013) informed that at least half of PhD graduates in many countries (e.g. the USA, Germany, Australia and Italy) do not aspire to an academic career, nor to find employment in academia. The knowledge economy increasingly requires the acquisition of specific skills on the part of graduates to compete in knowledge-intensive labor markets, which has increased the need for closer cooperation between education and the labor market. This resulted in the rise of hybrid doctoral degrees, also denoted as such as professional doctorates, work-based doctorates and industrial PhDs, that combine academic research with practical elements. Such fact is also associated with the opportunities commented by AEE and ADE, who highlighted the development of industry-oriented PhDs. In terms of weaknesses, there seems to be a consensus that the existing systematics for dissemination of learning in OE are not enough to support a close relationship between researchers and practitioners in this ecosystem. A poor learning dissemination may imply ambiguity, problems with knowledge absorption and, subsequently, difficulties with the knowledge application. Another cause for this issue might be associated with the misalignment in the form of knowledge registration in both academia and industry, which was also evidenced by Gerbin and Drnovsek (Citation2020). PEE and ADE suggested that this misalignment can threaten the effectiveness of OE knowledge retrieval as academics and practitioners often utilize different means to register the information. Thus, the following proposition is developed:

Proposition 2

The OE knowledge retrieval is likely to be strengthened by the insertion of researchers as part of the industry workforce, weakened by poor knowledge sharing, enhanced by the development of industry-oriented PhDs, and threatened by the misalignment in the knowledge registration.

Knowledge transfer seeks to organize, create, capture or distribute knowledge and ensure its availability for whomever may need (Foray & Lundvall, Citation1998). Both AEE and ADE indicated that one of the aspects that strengthens the activity between OE’s research and practice is the current revision of academics’ performance indicators. As universities’ performance management systems advance, metrics related to industry engagement have been incorporated as part of researchers’ goals, fostering more active participation with industry (Mercer, Citation2019). In opposition, limitations imposed by confidentiality agreements between industry and academia impair a smoother OE knowledge transfer. PEE and PDE claimed that an opportunity to enhance such OE knowledge transfer relies on the incoming workforce. Millennials and post-millennials are already the largest portion of the workforce in the USA since 2016 (Fry, Citation2018). According to Tortorella et al. (Citation2019), members from these generations are usually well-educated, rapid learners who are more familiar with OE cutting-edge practices and technologies, increasing the likelihood to transfer knowledge from research to practice. As for the threats, miscommunication between researchers and practitioners and existing terminology issues may jeopardize knowledge transfer. For instance, Marxt and Hacklin (Citation2005) argued that differences in terminologies can negatively impact activities related to product design and development, leading to redundancies and misinterpretations that may delay the time-to-market. Therefore, these arguments give rise to the following proposition:

Proposition 3

The OE knowledge transfer is likely to be strengthened by the revision of academics’ performance indicators, weakened by the limitations imposed by confidentiality agreements, enhanced by the highly skilled incoming workforce, and threatened by miscommunication and terminology issues.

Finally, the application of OE knowledge appears to be the activity in which there was the greatest agreement level between academics and practitioners. First, experts from all groups acknowledged that the relationship between OE’s research and practice can support the solution of complex industry problems. Such recognition clearly indicates a strength of this relationship in terms of knowledge application. Further, regarding the weaknesses, AEE, ADE and PDE commented that there is still a lack of empathy between OE’s research and practice. This can reduce the openness to new ideas and, hence, mitigate the OE knowledge application. Nevertheless, experts’ comments raised a relevant alternative to curb this. As the manufacturing companies face an increasing competitiveness, margins are reduced and new management approaches should be conducted to keep the business profitable. This creates a great opportunity to strengthen the ties between OE’s research and practice, so that novel techniques, methods and approaches conjointly developed by both can be incorporated into practice. Rogers (Citation2016) highlighted that in the manufacturing industry, chemical, computer and electronic products, pharmaceutical and medicines, automotive and aerospace, and machinery are the sectors that have been heavily investing in research and development due to quality, productivity and sustainability performance requirements. With regards to threats, interviewees mentioned that the difference between academia and industry responsiveness can affect OE knowledge application. This responsiveness differences tend to become more apparent when involving problem-solving activities, in which the behaviors from researchers and practitioners often differ in the ecosystem. This responsiveness difference may be intrinsically related with the short- and long-term orientation from practitioners and researchers, respectively. Hence, to better investigate these facts, the following proposition was raised:

Proposition 4

The OE knowledge application is likely to be strengthened by the need to solve complex problems through the relationship between research and practice, weakened by the lack of empathy between researchers and practitioners, enhanced by the high competitiveness industry requirements, and threatened by the different responsiveness levels between academia and industry.

6. Conclusions

This research examined the relationship between research and practice on OE. A qualitative, empirical approach was conducted in which experts from academia and industry located in both emerging and developed economies were interviewed. Content analysis of the collected data was framed within an ecological view of the KM activities, giving rise to four propositions for further theory testing and validation. Findings present contributions to both theory and practice, which are discussed as follows.

From a theoretical point of view, this investigation indicated that, despite the efforts to expand the knowledge on OE in the past decades, there is still a gap between in the relationship between research and practice. Such gap may be aggravated by the way both academics and practitioners have performed the creation, retrieval, transfer and application of OE knowledge. Nevertheless, there seems to be a common awareness about this gap, which represents an important step towards its mitigation. Additionally, academics and practitioners appear to understand the required countermeasures to reduce the distance between OE’s research and practice, regardless of the socioeconomic context in which they are inserted. This may lead to more cohesiveness between what is developed in theory and what is observed in practice, resulting in a more effective knowledge ecosystem.

In terms of practical implications, due to the growing complexity of problems faced by organizations and their supply chains, such as severe material disruptions, workforce shortage, high competitiveness, advanced technologies integration, etc., the development of research on OE has been more important than ever. Nevertheless, it is imperative that such research assertively approaches those problems in a coherent manner. This study contributes to the development of a more collaborative relationship between OE’s research and practice, which may positively impact the performance of manufacturing industries. Therefore, strengthening the collaboration between industry and academia may facilitate the achievement of OE, and avoid the development of isolated and/or outdated initiatives from both researchers and practitioners.

A few limitations are worth mentioning. First, being a qualitative study, the data collection and analysis are usually reasons for concern. Although all required countermeasures to ensure reliability and consistency in the analysis were performed, the consolidation of the data is subject to authors’ interpretation. Further studies utilizing complementary data collection methods could be carried out to crosscheck the results and validate our propositions. Second, the ecosystem analyzed in this study encompassed academia and industry as main agents for knowledge creation, retrieval, transfer and application. However, there may be other important agents, such as government institutions, regulatory agencies and non-profit organizations. Future research could expand the ecosystem to further involve these agents when discussing the knowledge in OE.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 25(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

- Alemsan, N., Tortorella, G., Rodriguez, C., Jamkhaneh, H.B., & Lima, R. (2022). Lean and resilience in the healthcare supply chain–a scoping review. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 13(5), 1058–1078. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-07-2021-0129

- Anand, J., McDermott, G., Mudambi, R., & Narula, R. (2021). Innovation in and from emerging economies: New insights and lessons for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(4), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00426-1

- Asif, M., Fisscher, O., Bruijn, E., & Pagell, M. (2010). Integration of management systems: A methodology for operational excellence and strategic flexibility. Operations Management Research, 3(3-4), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-010-0037-z

- Bag, S., Wood, L., Xu, L., Dhamija, P., & Kayikci, Y. (2020). Big data analytics as an operational excellence approach to enhance sustainable supply chain performance. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104559

- Barratt, M., Choi, T., & Li, M. (2011). Qualitative case studies in operations management: Trends, research outcomes, and future research implications. Journal of Operations Management, 29(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.06.002

- Basu, R. (2004). Six-sigma to operational excellence: Role of tools and techniques. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, 1(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSSCA.2004.005277

- Bigelow, M. (2002). How to achieve operational excellence. Quality Progress, 35(10), 70.

- Bittencourt, V., Alves, A., & Leão, C. (2021). Industry 4.0 triggered by lean thinking: Insights from a systematic literature review. International Journal of Production Research, 59(5), 1496–1510. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1832274

- Boddy, C. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053

- Bossert, J.L. (2021). Quality function deployment: A practitioner's approach. CRC Press.

- Botchie, D., Damoah, I.S., & Tingbani, I. (2021). From preparedness to coordination: Operational excellence in post-disaster supply chain management in Africa. Production Planning & Control, 32(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1680862

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis) conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’(2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588

- Bray, D. (2007). SSRN-knowledge ecosystems: A theoretical lens for organizations confronting hyper turbulent environments. Papers. ssrn. com.

- Burton, H., & Pennotti, M. (2003). The enterprise map: A system for implementing strategy and achieving operational excellence. Engineering Management Journal, 15(3), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2003.11415211

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Carvalho, A., Sampaio, P., Rebentisch, E., Carvalho, J., & Saraiva, P. (2019). Operational excellence, organisational culture and agility: The missing link? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(13-14), 1495–1514. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1374833

- Chandra, C., & Kumar, S. (2000). Supply chain management in theory and practice: A passing fad or a fundamental change? Industrial Management & Data Systems, 100(3), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570010286168

- Chang, V., & Tan, A. (2013). An ecosystem approach to knowledge management. In 7th international conference on knowledge management in organizations: Service and cloud computing (pp. 25–35). Springer.

- Chen, D., Liang, T., & Lin, B. (2010). An ecological model for organizational knowledge management. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 50(3), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2015.11645767

- Cheng, L., & Leong, S. (2017). Knowledge management ecological approach: A cross-discipline case study. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(4), 839–856. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2016-0492

- Chiarini, A., & Kumar, M. (2020). Lean six sigma and industry 4.0 integration for operational excellence: Evidence from Italian manufacturing companies. Production Planning & Control, 1–18.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

- Dahlgaard, J., & Dahlgaard-Park, S. (1999). Integrating business excellence and innovation management: Developing a culture for innovation, creativity and learning. Total Quality Management, 10(4-5), 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954412997415

- Deloitte. (2021). 2022 Manufacturing industry outlook. Accessed November 22, 2021, from https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/energy-and-resources/articles/manufacturing-industry-outlook.html

- Dev, N., Shankar, R., & Qaiser, F. (2020). Industry 4.0 and circular economy: Operational excellence for sustainable reverse supply chain performance. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104583

- Dieppe, A. (2021). Global productivity: Trends, drivers, and policies. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1608-6.

- Dubé, L., & Paré, G. (2003). Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices, trends and recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 597–635. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036550

- Durst, S., & Zieba, M. (2019). Mapping knowledge risks: Towards a better understanding of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1538603

- Edgeman, R. (2018). Excellence models as complex management systems: An examination of the Shingo operational excellence model. Business Process Management Journal, 24(6), 1321–1338. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-02-2018-0049

- Erro-Garcés, A. (2019). Industry 4.0: Defining the research agenda. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 28(5), 1858–1882. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-12-2018-0444

- Farooq, R. (2018). Developing a conceptual framework of knowledge management. International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(1), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-07-2018-0068

- Fettermann, A. (2021). 5 Industrial manufacturing trends impacting your operations. Godfrey, Industry and Research. Accessed November 22, 2021, from https://www.godfrey.com/insights/industry-and-research/5-manufacturing-trends-impacting-your-operations

- Fettermann, D., Cavalcante, C., Almeida, T., & Tortorella, G. (2018). How does industry 4.0 contribute to operations management? Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 35(4), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2018.1462863

- Fok-Yew, O., & Ahmad, H. (2014). Management of change and operational excellence in the electrical and electronics industry. International Review of Management and Business Research, 3, 723–739.

- Foray, D., & Lundvall, B. (1998). The knowledge-based economy: From the economics of knowledge to the learning economy. In The economic impact of knowledge (pp. 115–121).

- Found, P., Lahy, A., Williams, S., Hu, Q., & Mason, R. (2018). Towards a theory of operational excellence. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(9-10), 1012–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1486544

- Found, P., Samuel, D., & Lyons, J. (2017). From lean production to operational excellence. In M. Starr, & S. Gupta (Eds.), The Routledge companion to production and operations management (pp. 234–253). Routledge.

- Fry, R. (2018). Millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. Labor force. Pew Research Center. Accessed November 26, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/11/millennials-largest-generation-us-labor-force/

- Fugard, A., & Potts, H. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453

- Gerbin, A., & Drnovsek, M. (2020). Knowledge-sharing restrictions in the life sciences: Personal and context-specific factors in academia–industry knowledge transfer. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(7), 1533–1557. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2019-0651

- Gólcher-Barguil, L., Nadeem, S., & Garza-Reyes, J. (2019). Measuring operational excellence: An operational excellence profitability (OEP) approach. Production Planning & Control, 30(8), 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1580784

- Grant, R., Shani, R., & Krishnan, R. (1994). TQM's challenge to management theory and practice. MIT Sloan Management Review, 35, 25.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Guest, G., Namey, E., Taylor, J., Eley, N., & McKenna, K. (2017). Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: Findings from a randomized study. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1281601

- Henríquez-Machado, R., Muñoz-Villamizar, A., & Santos, J. (2021). Sustainability through operational excellence: An emerging country perspective. Sustainability, 13(6), 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063165

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Humphrey, A. (2005). SWOT analysis. Long Range Planning, 30, 46–52.

- Järvi, K., Almpanopoulou, A., & Ritala, P. (2018). Organization of knowledge ecosystems: Prefigurative and partial forms. Research Policy, 47(8), 1523–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.007

- Ketokivi, M., & Choi, T. (2014). Renaissance of case research as a scientific method. Journal of Operations Management, 32(5), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.03.004

- Lasi, H., Fettke, P., Kemper, H., Feld, T., & Hoffmann, M. (2014). Industry 4.0. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(4), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-014-0334-4

- Latham, J. (2008). Building bridges between researchers and practitioners: A collaborative approach to research in performance excellence. Quality Management Journal, 15(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2008.11918053

- Lista, A.P., & Tortorella, G. (2022). Integration of industry 4.0 technologies and knowledge management systems for operational performance improvement. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 55(10), 2042–2047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.10.008

- Malhotra, Y. (1999). Knowledge management for organizational white waters: An ecological framework. Knowledge Management, 2, 18–21.

- Malhotra, Y. (2002). Information ecology and knowledge management: Toward knowledge ecology for hyperturbulent organizational environments. In Encyclopedia of life support systems (EOLSS). UNESCO.

- Mangla, S., Kusi-Sarpong, S., Luthra, S., Bai, C., Jakhar, S., & Khan, S. (2020). Operational excellence for improving sustainable supply chain performance. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, 162, 105025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105025

- Mangla, S., & Luthra, S. (2022). When challenges need an evaluation: For operational excellence and sustainability orientation in humanitarian supply and logistics management. Production Planning & Control, 33(6-7), 539–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1834129

- Marxt, C., & Hacklin, F. (2005). Design, product development, innovation: All the same in the end? A short discussion on terminology. Journal of Engineering Design, 16(4), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544820500131169

- McCarthy, P., & Wienk, P. (2019). Who are the top PhD employers?. Advancing Australia’s knowledge economy. Accessed November 26, 2021, from https://amsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/advancing_australias_knowledge_economy.pdf

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., & Douglas, J. (2021). Exploring the use of operational excellence methodologies in the era of COVID-19: Perspectives from leading academics and practitioners. The TQM Journal, 33(8), 1647–1665. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-01-2021-0016

- Mercer. (2019). Keys for successful industry-education engagement. Accessed November 26, 2021, https://www.mercer.com.au/content/dam/mercer/attachments/asia-pacific/australia/our-thinking/au-2019-universities-pov-brochure-july-2019.pdf

- Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Moktadir, M., Dwivedi, A., Rahman, A., Jabbour, C., Paul, S., Sultana, R., & Madaan, J. (2020). An investigation of key performance indicators for operational excellence towards sustainability in the leather products industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3331–3351. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2575

- Montgomery, D., & Woodall, W. (2008). An overview of six sigma. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique, 329–346.

- Narasimhan, R. (2014). Theory development in operations management: Extending the frontiers of a mature discipline via qualitative research. Decision Sciences, 45(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12072

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- Oakland, J. (2014). Total quality management and operational excellence: Text with cases. Routledge.

- Ori, M. (2013). The rise of industrial PhDs. University World News. Accessed November 26, 2021, from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20131210130327534

- Prockl, G. (2005). Supply chain diagnostics to confront theory and practice—Re-questioning the core of supply chain management. In Research methodologies in supply chain management (pp. 397–412). Physica-Verlag HD.

- PwC. (2020). Industrial manufacturing trends 2020: Succeeding in uncertainty through agility and innovation. Accessed November 22, 2021, from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceo-survey/2020/trends/industrial-manufacturing-trends-2020.pdf

- Rogers, S. (2016). Top 10 Industries that Hire Research and Development Employees. Interesting Engineering. Accessed November 26, 2021, from https://interestingengineering.com/top-10-research-development

- Rosenberg, M. (2001). E-Learning: Strategies for delivering knowledge in the digital Age. McGraw-Hill.

- Roth, N., Deuse, J., & Biedermann, H. (2020). A framework for system excellence assessment of production systems, based on lean thinking, business excellence, and factory physics. International Journal of Production Research, 58(4), 1074–1091. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2019.1612113

- Sartal, A., & Vázquez, X. (2017). Implementing information technologies and operational excellence: Planning, emergence and randomness in the survival of adaptive manufacturing systems. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 45, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2017.07.007

- Sawhney, R., Treviño-Martinez, S., de Anda, E., Tortorella, G., & Pourkhalili, O. (2020). A conceptual people-centric framework for sustainable operational excellence. Open Journal of Business and Management, 8(3), 1034–1058. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2020.83066

- Shetty, S. (2020). Determining sample size for qualitative research: What is the magical number. InterQ. Accessed January 26, 2021, from https://interq-research.com/determining-sample-size-for-qualitative-research-what-is-the-magical-number/

- Shingo Institute. (2014). Shingo Institute – Shingo Model. Utah, USA. Retrieved from Shingo Institute – Utah University. https://shingo.org/model

- Shrivastava, P. (1983). A typology of organizational learning systems. Journal of Management Studies, 20(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1983.tb00195.x

- Shrivastava, P. (1998). Knowledge ecology: Knowledge ecosystems for business education and training. Unpublished, last edited Jan. Accessed November 11, 2021, from https://web.archive.org/web/20170825081451/http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/shrivast/KnowledgeEcology.html

- Slack, N., Lewis, M., & Bates, H. (2004). The two worlds of operations management research and practice: Can they meet, should they meet? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(4), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570410524640

- Soboh, R., Lansink, A., Giesen, G., & Van Dijk, G. (2009). Performance measurement of the agricultural marketing cooperatives: The gap between theory and practice. Review of Agricultural Economics, 31(3), 446–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2009.01448.x

- Soltani, E. (2005). Conflict between theory and practice: TQM and performance appraisal. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 22(8), 796–818. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656710510617238

- Sony, M. (2019). Implementing sustainable operational excellence in organizations: An integrative viewpoint. Production & Manufacturing Research, 7(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693277.2019.1581674

- Soto, F. (2017). A better definition of operational excellence. Wilson Perumal & Company. Accessed October 2, 2020, from https://www.wilsonperumal.com/blog/a-better-definition-of-operational-excellence

- Sriyakul, T., Singsa, A., Sutduean, J., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2019). Effect of cultural traits, leadership styles and commitment to change on supply chain operational excellence. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 16(7), 2967–2974. https://doi.org/10.1166/jctn.2019.8203

- The World Bank. (2019). Research and development expenditure (% of GDP) – China and WEF report published 2019. NOTE data points in the WEF 2019 report were from the GERD % of GDP dataset from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

- The World Bank. (2021). Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP). Accessed November 22, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS

- Tortorella, G., Cauchick-Miguel, P., Frazzon, E., Portioli-Staudacher, A., & Kumar, M. (2022b). Teaching and learning of industry 4.0: Expectations, drivers, and barriers from a knowledge management perspective. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1–16.

- Tortorella, G., Cauchick-Miguel, P., Li, W., Staines, J., & McFarlane, D. (2021a). What does operational excellence mean in the fourth industrial revolution era? International Journal of Production Research, forthcoming.

- Tortorella, G., Fogliatto, F., Vergara, A., Vassolo, R., & Sawhney, R. (2020b). Healthcare 4.0: Trends, challenges and research directions. Production Planning & Control, 31(15), 1245–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1702226

- Tortorella, G., Miorando, R., Meiriño, M., & Sawhney, R. (2019). Managing practitioners’ experience and generational differences for adopting lean production principles. The TQM Journal, 31(5), 758–771. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-02-2019-0041

- Tortorella, G., Narayanamurthy, G., & Staines, J. (2021b). COVID-19 implications on the relationship between organizational learning and performance. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 19(4), 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1909430

- Tortorella, G., Pradhan, N., Anda, E., Martinez, S., Sawhney, R., & Kumar, M. (2020a). Designing lean value streams in the fourth industrial revolution era: Proposition of technology-integrated guidelines. International Journal of Production Research, 58(16), 5020–5033. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1743893

- Tortorella, G., Prashar, A., Vassolo, R., Cawley Vergara, A.M., Godinho Filho, M., & Samson, D. (2022a). Boosting the impact of knowledge management on innovation performance through industry 4.0 adoption. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1–17.

- Treacy, M., & Wiersema, F. (1995). The discipline of market leaders: Choose your customers, narrow your focus, dominate your market. Perseus Books.

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Voss, C., Tsikriktsis, N., & Frohlich, M. (2002). Case research in operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210414329

- Womack, J., Jones, D., & Roos, D. (2007). The machine that changed the world: The story of lean production–Toyota's secret weapon in the global car wars that is now revolutionizing world industry. Simon and Schuster.

- Yang, J., Chae, S., Kwak, W., Kim, S., & Kim, I. (2009). Agent-based approach for revitalization strategy of knowledge ecosystem. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan, 78(3), 034803–034803. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.78.034803

- Zanon, L.G., Ulhoa, T.F., & Esposto, K.F. (2021). Performance measurement and lean maturity: Congruence for improvement. Production Planning & Control, 32(9), 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1762136

Appendix: Semi-structured interview protocol

What is your professional background? Please, provide a brief description of your professional experience.

How do you define Operational Excellence? Please, justify your answer and give examples.

Regarding both the research and practice on Operational Excellence in manufacturing environment, please, tell us how you perceive their relationship according to the following aspects:

Strengths

Weaknesses

Opportunities

Threats

Please, justify your answer and give examples.