Adequate management of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) is an unmet need. As commonly seen in clinical practice, the risk of a subsequent occurrence of CDI increases with the number of times a patient has CDI [Citation1–3]. Trials and guidelines addressing rCDI make distinctions between first recurrence and multiple recurrences in terms of treatment strategies [Citation1–3]. Many terms have been used to describe rCDI, including second or subsequent CDI recurrence, ≥1 recurrence of CDI, ≥3 confirmed occurrences, ≥2 recurrences, or multiply recurrent [Citation1–6]. Unfortunately, the myriad of ways to describe at what point preventative therapy should be considered for a patient with rCDI can be confusing.

Fecal microbiota spores, live-brpk (VOWST™ [Seres Therapeutics]; formerly SER-109; now VOS for Vowst Oral Spores) is a microbiota-based therapeutic characterized by a bacterial spore suspension of Firmicutes in capsules for oral administration indicated to prevent the recurrence of CDI in individuals ≥18 years of age after completing antibacterial treatment for rCDI [Citation7]. Data are published on the safety and efficacy of VOS for adults after a first recurrence [Citation6] and those who have had CDI ≥ 3 times within a finite time frame (up to 12 months) [Citation4–6]. We consider prescribing VOS for patients with rCDI, regardless of the number of prior recurrences especially in the context of infection severity and individual patient needs.

Treatment and prevention should be aimed at individuals with active infection versus those who are simply colonized [Citation2,Citation3]. Diagnostic accuracy, in addition to physician discretion, is important for identifying patients with CDI and candidates for prevention. Strategies to prevent recurrence may include using narrow-spectrum antibiotics, restoring the microbiome, or enhancing the immune system of the patient [Citation1,Citation2]. It is key to identify those who are truly at risk of future recurrence and not those merely colonized with Clostridioides difficile when considering the use of therapeutics intended to prevent recurrence. VOS trials identified patients with CDI in 3 ways: 1) symptomatically with ≥ 3 unformed bowel movements over 2 days, 2) objectively with a positive Clostridioides difficile toxin test (toxin enzyme immunoassay or cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay) or toxin gene detection via polymerase chain reaction, and 3) in response to antibiotic treatment [Citation4–6].

The primary concerns of the treating clinician are therapeutic efficacy and safety considerations. VOS, after standard-of-care antibiotics, reduced the risk of CDI recurrence by 68% compared with antibiotics alone [Citation4]. The rate of recurrence in patients receiving VOS was 12% versus 40% in the placebo arm (relative risk, 0.32; 95% confidence interval, 0.18–0.58; P < 0.001) [Citation4]. Serious adverse effects and deaths occurring in trials were not considered by the study investigators to be related to VOS [Citation4,Citation6].

Infections caused by pathogen transmission are a concern for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Although they can be mitigated by strict screening of donor and donor fecal specimens according to US Food and Drug Administration guidance [Citation8,Citation9], the concern remains. A microbiota-based therapeutic for oral administration such as VOS where, as part of the manufacturing process, the Firmicutes spore suspension is treated with ethanol to kill organisms that are not spores, followed by filtration steps to remove solids and residual ethanol, mitigates this concern [Citation7]. Expected and common adverse events (AEs) are generally similar among the microbiome therapeutics (irrespective of the route of administration) and include gastrointestinal AEs [Citation4–6,Citation10,Citation11]. Common AEs previously reported as possibly related to FMT were transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, constipation, and excess flatulence [Citation10], whereas common AEs occurring at a higher rate versus placebo were abdominal pain, diarrhea, abdominal distension, flatulence, and nausea for RBX2660 (also known as fecal microbiota, live-jslm or FMBL) [Citation11,Citation12] and abdominal distension, constipation, and diarrhea for VOS [Citation4].

Shared decision making between providers and patients is key in selecting a treatment by considering additional factors, such as potential improvements to quality of life, consideration of mild to moderate safety concerns, and the logistics of administration. The negative effect of rCDI on a patient’s quality of life and functioning should not be overlooked [Citation13,Citation14]. VOS improved overall health-related quality of life and individual domain scores (physical, mental, and social) of the disease-specific Clostridioides difficile Quality of Life Survey (Cdiff32) 1 week after treatment and up to 8 weeks after treatment versus placebo in patients in the phase 3 ECOSPOR III trial [Citation13]. This could potentially translate to fewer missed days at work; however, more information on indirect costs is needed.

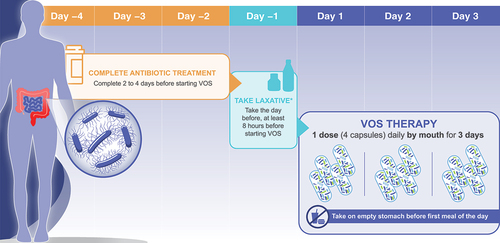

Logistically, several administration factors should be kept in mind when using microbiota-based therapeutics, including VOS. Limitations of existing microbiome therapies are the clinic resources (ie, staff and facility) needed to store, prepare, and administer FMT rectally, via nasogastric tube, or via colonoscopy (including the need for anesthesia), or FMBL rectally [Citation11,Citation15]. FMBL also requires storage in an ultracold freezer, unless used within 5 days [Citation11]. VOS is initiated 2 to 4 days following completion of antibiotic treatment. On the day before starting VOS, the patient needs to take a laxative (10 oz magnesium citrate or based on medical judgment, 250 mL of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution) to remove any residual antibiotic that may inactivate the live Firmicutes spores [Citation7]. At least 8 hours following the laxative, VOS is taken orally as 4 capsules for 3 consecutive days [Citation7] () and can be self-administered by the patient, thus offering a more convenient option for the patient, clinician, and their staff. VOS is comprised of live Firmicutes spores that can be stored at room temperature (36°F–77°F) [Citation7]. Except for cases where a patient cannot swallow, it is likely that most patients will prefer an oral option.

Figure 1. Prescribing considerations for VOS (formerly SER-109). *296 mL (10 oz) of magnesium citrate. Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution was used for participants with impaired kidney function in trials (250 mL GoLYTELY, not approved for this use).

Two factors will be key to support VOS use in routine clinical practice: 1) education, and 2) accessibility. Clinicians treating patients with CDI regularly are likely open to prescribing VOS. Identifying the right patient and using the drug correctly will require education on how to diagnose rCDI accurately, when to use VOS, and how to prescribe it. Education should be aimed not only at prescribers, but also nurses, pharmacists, and clinic or other support staff who help monitor patients for AEs, identify completion of antibiotic treatment, remind patients to take a laxative the day before, and support treatment adherence. Patients should be educated on when and how to take VOS and provided with expectations for efficacy and safety. Setting up streamlined processes on paper, in the electronic medical record, or in the office can help manage the burden of prior authorizations and/or appeals; these are strategies that clinicians can implement to improve accessibility. It is recognized that all microbiome therapies for rCDI will involve some sort of logistical consideration and planning. We hope that highlighting some of the practical considerations () will help clinicians think preemptively about VOS implementation and lessen the barriers to adopting the use of this microbiota-based therapeutic for oral administration in clinical practice.

Table 1. Practical questions and answers for clinicians when using VOS (formerly SER-109).

Declaration of interest

J Rosenberg has participated on an advisory board for Aimmune Therapeutics, a Nestlé Health Science company. T Ritter has participated on an advisory board for Aimmune Therapeutics, a Nestlé Health Science company. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or material discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium for their review work. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Stephanie Phan, PharmD, and Cheryl Casterline, MA (Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, USA), and funded by Aimmune Therapeutics, a Nestlé Health Science company and Seres Therapeutics.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johnson S, Lavergne V, Skinner AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 7;73(5):755–757. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab718

- Kelly CR, Fischer M, Allegretti JR, et al. ACG clinical guidelines: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jun 1;116(6):1124–1147. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001278

- van Prehn J, Reigadas E, Vogelzang EH, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 update on the treatment guidance document for Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Dec;27 Suppl 2:S1–S21.

- Feuerstadt P, Louie TJ, Lashner B, et al. SER-109, an oral microbiome therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jan 20;386(3):220–229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2106516

- McGovern BH, Ford CB, Henn MR, et al. SER-109, an investigational microbiome drug to reduce recurrence after Clostridioides difficile infection: lessons learned from a phase 2 trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 15;72(12):2132–2140. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa387

- Sims MD, Khanna S, Feuerstadt P, et al. Safety and tolerability of SER-109 as an investigational microbiome therapeutic in adults with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a phase 3, open-label, single-arm trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Feb 1;6(2):e2255758. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55758

- VOWST (fecal microbiota spores, live-brpk) capsules, for oral administration. Prescribing information. [updated Apr 2023; cited May 3, 2023]. Available from: https://www.serestherapeutics.com/our-products/VOWST_PI.pdf

- Food and Drug Administration. Fecal microbiota for transplantation: safety alert - Risk of serious adverse events likely due to transmission of pathogenic organisms. [updated Apr 7, 2020; cited May 3, 2023]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fecal-microbiota-transplantation-safety-alert-risk-serious-adverse-events-likely-due-transmission

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Enforcement policy regarding investigational new drug requirements for use of fecal microbiota for transplantation to treat Clostridioides difficile infection not responsive to standard therapies: Guidance for industry. [updated Nov 2022; cited May 3, 2023]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/86440/download

- Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016 Jan 12;315(2):142–149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18098

- REBYOTATM (fecal microbiota, live - jslm) suspension, for rectal use [prescribing information]. [updated Nov 2022; cited May 4, 2023]. Available from: https://ferringus2.corporate-us.ferring.tech/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/12/9009000002_REBYOTA-PI_11-2022.pdf

- Khanna S, Assi M, Lee C, et al. Efficacy and safety of RBX2660 in PUNCH CD3, a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with a bayesian primary analysis for the prevention of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Drugs. 2022 Oct;82(15):1527–1538.

- Garey KW, Jo J, Gonzales-Luna AJ, et al. Assessment of quality of life among patients with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection treated with investigational oral microbiome therapeutic SER-109: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jan 3;6(1):e2253570. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53570

- Hengel RL, Schroeder CP, Jo J, et al. Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection worsens anxiety-related patient-reported quality of life. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022 May 14;6(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00456-9

- Sandhu A, Chopra T. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile, safety, and pitfalls. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211053105.