ABSTRACT

This article uses intimacy and architecture as a way to tell the lesser-known story of men and the domestic in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Belgium. Drawing upon little-known interior design and architecture magazines, domestic manuals and photographs, I highlight how male architects and critics of architecture contributed to the making of domesticity. I show how ‘intimacy’ was used as a deceptive concept to frame the home as a restful refuge, as well as a catalyst for creative experimentation.

Introduction

‘Separation from the workplace, privacy, comfort and focus on the family’: in his introduction to Not at Home. The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, Reed associates these values with domesticity and the home. He argues that: ‘the home has been positioned as the antipode to high art. Ultimately, in the eyes of the avant-garde, being undomestic came to serve as a guarantee of being art.’ (Citation1996, 7). While he acknowledges that ‘the domestic realm has offered specific artists or groups the potential to evade aesthetic and social conventions’ (Reed Citation1996, 16), these attempts failed to significantly alter the paradigm opposing modernism to the domestic in the long run. The opposition modernism/domestic follows typical gender divisions: women, the home and the domestic; men, art and the public. This article destabilises this opposition by focusing on Belgian male architects and critics of architecture who contributed to the making of domesticity by designing and writing about the home. I retrace their involvement with the domestic by studying little-known Belgian interior design and architecture magazines (L’Émulation, 1874–1914 and 1921-1939; Le Cottage, 1903–1905 and Le Home, 1908–1915 and 1920-1926). These publications show that homes were at the heart of lively societal debates, in which a large number of men participated. It contradicts both the myths that the public and the private realms were distinct and that men were almost exclusively involved with the public sphere. However, these magazines reveal what I identify as a male perspective on domesticity, which largely ignores the messiness of ‘mundane’ housekeeping. Homes are framed as a place of comforting intimacy for men which means that the labour necessary in producing and maintaining the illusion of a flawless domestic environment is rendered invisible.

The definition of the domestic as ‘belonging or relating to the home, house or family’ (Cambridge English Dictionary Citation2020) encompasses the values listed by Reed while also leaving room to think about the ways in which some of these values are actively upheld.Footnote1 Intimacy is one of the notions at the core of this process: by branding the home as an ‘intimate refuge from work’ for men, domestic manuals and architecture and design magazines implicitly excluded them from participating in domestic work. Intimacy was also a prism through which male architects thought about the layout of houses. Rather than aiming to impress the occasional visitor, they advocated for homes to cater to their inhabitants’ needs, discarding at the same time the need for domestic servants. Homes became more rational and practical, but also more ‘intimate’ as a result.

Furthermore, I consider how domesticity is staged in Art Nouveau architecture and contemporary interior photographs through an emphasis on the visual qualities of interior spaces. This aesthetic and distanced point of view fits a larger story according to which men are outsiders to the domestic interior. Domestic interiors become spaces to look at rather than to live in. Having established the relevance of considering men and domesticity in nineteenth-century debates and architecture practices, I turn to further questioning the association between domesticity and conformity, highlighted by Fraiman (Citation2017). I show how a progressive domestic environment could also support artistic creation which subverted values traditionally associated with domesticity and the home. ‘Comfort’, in the realm of fashion design, was radically reinterpreted by the architect Henry van de Velde and his wife Maria Sèthe, in a way that was fostered by the intimacy of their home. These considerations help to enrich the meanings of domesticity and intimacy, by showing how ‘intimacy’ can both be a deceptive concept to frame the home as a restful refuge, as well as a catalyst for creative experimentation.

This article focuses on Belgium as a country where the domestic context was a crucial site for artistic innovation and sociability (Brogniez Citation2018). Art Nouveau architecture flourished with the construction of private houses; avant-garde exhibitions were held in galleries that looked like private houses (Block Citation1991) and artists built or decorated their own homes (Draguet Citation2018; Moran Citation2018), to name but just a few examples. A broader analysis considering the role played by the domestic sphere in artistic creation and discourses on architecture and design has yet to be undertaken. Moreover, centring men and their role in the ‘making’ of domesticity is unprecedented in the case of fin-de-siècle Belgium. It allows for a reconsideration of the dynamics at the intersection of gender, modernity, the private and the public sphere and of the ways the notions of intimacy and domesticity can uphold or subvert values traditionally associated with the home. This rethinking of the intimate domestic sphere as both modern and non-modern is crucial to our understanding of the late nineteenth century home.

Men and the Domestic

The traditional association of women with the home has obscured men’s involvement with the domestic. At the same time, it has reinforced ‘bias against domesticity as spaces and practices strongly associated with women’ (Fraiman Citation2017, 3). As a result, male modernists’ involvement with the domestic sphere has been underexplored even though modernist artists did not erase the domestic and the intimate from their work. Pioneering work has been done by Kuenzli in The Nabis and Intimate Modernism (Citation2017), where she writes about the site-specific works the French group of painters created for private interiors. For Kuenzli, the Nabis have been overlooked because of their involvement with the decorative and the domestic, which was dismissed as passive and ‘a turning away from the modernist dream of public art’ (Kuenzli Citation2017, 11). She insists on the important legacy of the Nabis, in particular how they influenced later artists by aiming at creating unified environments (Kuenzli Citation2017, 19–20). Ultimately, she seeks to expand what modernism might encompass:

Instead of restricting domestic space to women, my work […] challenges the following binaries that have structured seminal accounts of modernism: pictorial/decorative, active/passive, masculine/feminine, public/private, heroism/housework. (Kuenzli Citation2017, 13)

Scholars have long debated whether the notion of separate spheres, according to which men and women are allocated different spheres of action and influence, reflected what was happening at the time or was designed to influence society, whether in the nineteenth century or more recently (Berry Citation2006, 171; Wolff Citation2008, 22–23). Beyond the debate concerning the ideological or natural character of this framework, Marcus (Citation1999) has suggested the value of critical scepticism when it comes to its hegemony. It applied specifically to one class, the bourgeoisie, but it might not even be representative in that case (Marcus Citation1999, 7).Footnote2 Fraiman has identified several significant trends in the scholarship that attempt to go beyond this framework, for example by ‘providing more complex accounts of female lives and domestic realities across the centuries,’ including those of women marginalised by their class, race and/or sexuality. She mentions other approaches such as documenting ‘women’s experiences beyond the domestic sphere as well as the overlap between public and private life’ and formulating ‘an appreciative understanding of domestic knowledge, rituals, and relationships’ (Citation2017, 2). Other scholars have questioned the definition of the public sphere and its identification with political and/or economic aspects (those being less accessible for women) (Balducci and Belnap Jensen Citation2017, 3). Recent interest in shaping a more critical understanding of nineteenth-century masculinities has also proven crucial in reassessing the relevance of the separate spheres model (Balducci, Belnap Jensen, and Warner Citation2010).

Fraiman’s approach in Extreme Domesticity is particularly persuasive as she maps ‘domesticity from the margins’ to ‘contest received ideas about where and with whom domesticity lies’ (Citation2017, 5). She focuses on women that are not conforming to the traditional expectation of their gender and class but also includes male homemakers. Her aim is to undo the link that connects women and domesticity, on the one hand, and conformity, on the other hand, arguing that domesticity is not conservative per se. Other researchers point towards the relevance and creative potential of the home in modernism. Rosner considers writers, both male and female, that were offering ‘new proposals for domesticity’ and were searching for ‘new artistic forms of representing intimacy and daily life’ (Citation2005, 13). She states: ‘[m]odernist literature is broadly informed by – and indeed contributes to- the project of reconstruction of form, function and meaning of the home to meet the demands of modernity’ (Citation2005, 13). However, following Brown and her interpretation of Bernard Yack, it is important to state that my interest lies in the tensions between modern and non-modern practices associated with the home, domesticity and men, recusing the idea of modernity as a ‘coherent whole’ (Brown Citation2012, 215–17). In the following section, I discuss the architect Victor Horta and critics of architecture who did not necessarily try to subvert the binaries associated with modernity or show the creative potential of the home. They were involved with their domestic environment but were actively upholding the conservative values of domesticity. Re-examining these famous or anonymous men leads me, for example, to highlight the untold story of the interior design of an Art Nouveau house, which reinforced conservative hierarchies, and to reveal how critics of architecture pushed for changes in the hope of aligning more closely their stereotypical idea of the home as a ‘refuge’ with a rapidly evolving society.

Staging Domesticity

Although the family was a much-debated ideological notion at the time, a significant part of the contemporary discourse on this matter specifically focused on the role of women (Cheysson Citation1904, 341; Perrot Citation1999, 97; Silverman Citation1994, 69–81; Heymans Citation2018, 198–200; Singletary Citation2008, 41). Belgian domestic manuals and schoolbooks regularly reasserted that the morality, behaviour, and role of women at the centre of their family was supposed to be the basis in order to maintain society:

Après une journée de rude labeur, le mari n’est-il pas plus content lorsque, près d’une table bien servie, il trouve une épouse qui l’accueille le sourire sur les lèvres? Il se sent si heureux qu’il oublie ses fatigues, et, savourant les douceurs de l’intimité, il n’a nulle envie d’aller au dehors chercher des distractions. (Detienne and Voituron-Liénard Citation1901, 6)

Le bon gîte, hygiénique et confortable, est, comme le pain, nécessaire à la vie. Il enclot l’existence de la famille, le bonheur du ménage, l’intimité où l’on se retrempe dans la tendresse pour de nouveaux labeurs. Et ce n’est pas seulement la santé physique qu’il favorise c’est aussi la satisfaction morale qui découle normalement du bien-être. La maison morne et lamentable, le taudis de misère sale et ravagé, le galetas où l’indigence s’exaspère dans l’effroi des murs nurs, des meubles rares, tout cela c’est de l’exaltation pour la pauvreté et une souffrance nouvelle pour les malchanceux. La vie y paraît plus morne, parce que ce décor semble y exalter la détresse. La hargne y encolère bien mieux les caractères déjà aigris, et c’est le découragement que le travailleur y trouve au retour du labeur, au lieu de l’intimité heureuse qui est le réconfort des âmes simples. (Dupont Citation1908, 3)

At the end of the nineteenth-century, architecture was a profession in the making. Several architects achieved success with building private houses. Victor Horta, an Art Nouveau architect, is known to have made what he called ‘portrait houses’ which were tailored to the needs of his (mostly male) clients. The house he built for himself and his family () functioned partly as a showroom for demonstrating his talents, especially for the bel-étage, which is the most luxurious. However, the whole house demonstrates a close knowledge of household processes and habits. Careful attention has been given to ‘mundane’ details such as different methods of keeping dishes warm on their way to the dining room. A male toilet was built in the wall next to the bed for pressing morning needs. A column-shaped heater at the base of the staircase would allow his wife to stay warm while waiting for the carriage or the car. Technical innovations were used to streamline domestic tasks. Yet much of the attention Horta gave to such processes contributed to rendering them invisible. As in most bourgeois houses of the time, the servants’ quarters were carefully concealed, with a separate staircase serving the basement kitchen and the attic bedrooms. A buffet with a built-in hatch allowed dishes to be handed to the dining room without requiring a servant to walk into the room. Small details mentioned above, such as the toilet or the heating, were equally hidden: the toilet in a cupboard, and the heating in a decorative element. The result is a house where much of the actions that ‘belong to the family of gestures indispensable to survival and fundamental to culture’ (Fraiman Citation2017, 8) are pushed to the margins: cleaning, buying groceries, preparing food, providing warmth to the house, and so on. While the house is radically modern in its design, with an innovative use of steel, skylights and room partitions, it is nonetheless organised according to a strict hierarchy of spaces, people and tasks. It stages an illusion of a type of friction- and labour-less domesticity where basic needs can be ignored and still provided for, which is perpetuated by architecture and interior design magazines.

An interest in private houses and the domestic can also gradually be seen in the journal L’Émulation (1874–1939), published by the architectual organisation Société centrale d’architecture de Belgique. It began to include plans for private houses and then photographs of interiors, from the 1890s (Citation1891; Citation1892; Citation1896). However, these pictures focused on interior décor and were devoid of the traces of human lives. Very little in the pictures testify to the fact that these interiors were inhabited (). The photograph of the dining room of Mr Vanderkindere in L’Émulation does not show any trace of a dining table and the layout of the furniture seems to actively engage a viewer.Footnote3 Interior spaces are represented as seen from an external point of view rather than through the inhabitants’ intimate perspective. Similarly, Art Nouveau architect Victor Horta took care to open up perspectives for the gaze in his interior, putting an emphasis on vision as a way to embrace several spaces at the same time. In those cases, interiors are mainly presented as spaces to think about and to look at rather than to live in.

Figure 2. Salle à manger de Mr L. Vanderkindere, published in L’Emulation, June 1896, n° 6, pl. 50. ©CIVA.

Other journals go further in revealing a male perspective on domesticity. In the first issue of Le Cottage (1903-1905), its programme stated that its intended readership were ‘homeseekers’:

Homeseeker est une expression anglaise qui caractérise ‘une personne qui est à la recherche d’un home’, qui se demande où, quand, comment elle pourra établir son intérieur, son foyer, son home enfin, puisque la langue française a adopté ce mot charmant, qui signifie à lui seul et la maison et la maisonnée, le contenant physique, l’habitation claire et joyeuse, enfouie dans la verdure au milieu d’un grand jardin, bien saine et bien confortable, et le contenu moral, le foyer où l’on vit heureux au milieu de ceux qu’on aime.(‘Notre Programme’ Citation1903)

Because of its title, the magazine Le Home (1908-1915 and 1920-1926) seems broader in scope. It was mainly intended for a male readership. From 1910 on, a few pages were specifically marketed to women, typically focusing on fashion, crafts or housekeeping (‘Les Pages de la Femme’ Citation1913), whereas Le Cottage’s readership was not explicitly gendered. An additional step is taken with the magazine’s subtitle as it was rebranded as ‘revue illustrée de la famille’ in 1911. These changes corresponded to shifts in the editorial line as the magazine progressively went on to cover art and literature topics as well.

In both these journals, the range of topics covered is broad, ranging from architecture to urban planning, gardening, hygiene, furniture shopping and including reviews of exhibitions and conferences. A wide range of concerns are associated with the home and fit uneasily into a distinction between the private and public. While Le Cottage is led by a more progressive editorial board,Footnote4 Le Home takes on a more conservative approach. Yet, in both cases, ‘mundane’ details related to the activities of daily life (e.g. cleaning) are mostly left aside, either ignored or circumscribed to the women’s pages. Domestic work however, is discussed in several articles:

Nos habitations n’en deviendront que plus belles en devenant plus simples. Il ne faut pas croire que ces prévisions soient de simples suppositions; tous les architectes vous diront par exemple que le nombre des maisons nouvelles où l’on ne réserve plus de salon augmente de jour en jour, et c’est surtout dans les habitations des gens riches que cela se constate le mieux. Nos maisons, faites alors pour nous qui les habitons, non plus pour la montre, pour le paraître, n’en seront qure plus personnelles, plus intimes. Forcément elles deviendront plus en plus [sic] rationnelles et pratiques, de telle façon qu’elles nous donneront le maximum de confort avec le minimum d’effort: et ce résultat excellent sera dû, en grande partie, à ce que nous considérons aujourd’hui, peut-être à tort, comme une nuisance: la pénurie des domestiques. (‘Les Domestiques’ Citation1904, 138)

‘Ménagère, tu te plains des marches et de contre-marches fatigantes que ton ministère de chaque jour t’impose du matin au soir. Je n’ai pas craint parce que homme, d’en essayer cette besogne et il serait à souhaiter que tous mes frères en fassent autant durant quelques jours. Bien peu résisteraient à cette tâche surhumaine que la femme fournit toute l’année durant. Oui, je sais. Il y a les bonnes … Dans mon nid, cette étrangère, cette ennemie!!! me gâter mes meilleures moments, par cette présence!!! Non! Partageons la tâche, composons notre home en vue du travail. A côté du Hall, de la Chambre commune, aux dimensions maxima, donnant sur la rue, donnant sur le jardin, concentrant la vie totale de la famille, mettons la cuisine, mettons le laboratoire où s’élabore la force et la santé.’ (Heim Citation1910, 11–13)

On the basis of these journals, which have not been systematically investigated so far,Footnote5 it appears that men were far from having entirely severed their links with the domestic. It is therefore worth reconsidering the separation between the public world of work and the private home by investigating the perspective of both genders. These types of primary sources prove crucial in this endeavour. The question of what made a good home, as well as its ideal location, architecture and interior design were discussed at length. However, certain domestic tasks were contained within limits, whether on dedicated pages in magazines or in discussions of the servant’s quarters in architecture. This attempt at circumscribing mundane tasks to the margins turns domesticity into an image, rather than the repetition of gestures intended for maintaining daily life. Intimacy is a crucial notion in both erasing the work needed to produce and maintain a home and in promoting changes towards a more rational and practical interior (such as the suppression of the salon). In the name of ‘intimacy’, writers in Le Cottage and Le Home promoted changes that aimed to preserve the illusion of the home as a place for rest and ‘douceur’. Intimacy was hailed as the reason for drawing men to and keeping them in the home, as if they did not belong there in the first place. The next section looks at an artistic couple who, on the contrary, embraced the intimacy provided by the home to create a modern and creative lifestyle, which pushed back against and questioned the links between domesticity and conformity.

Subverting the Values of Domesticity

This section highlights the creative possibilities the domestic environment provided for an artist, through the example of the architect and designer Henry van de Velde and his wife, Maria Sèthe. Considering men’s involvement with the domestic helps to shed light on the creative partnerships with the women in their lives, which sustained their artistic careers. I subscribe to the notion of a ‘messy history’ (Scotford Citation1994), allowing us to discover all the significant ways women have participated in their male family members’ work and career. Partaking in ‘messy history’ aims to put all the meaningful partnerships artists have formed and that have supported them in their accomplishments in a fairer light, in a further undoing of binaries and oppositions. Roles, even traditional ones, cannot be dismissed (Scotford Citation1994, 382).

Not only could the home provide the ideal environment for creation – it could also be a freer space in which to experiment. Henry van de Velde and Maria Sèthe built their first home, the Bloemenwerf, in 1895, two years after they got married. It was Henry van de Velde’s first architectural creation. Determined to bring beauty in every aspects of life (Van de Velde Citation1992, 217), the couple took particular care in supervising the work and refining every detail. Van de Velde created several pieces of furniture while Sèthe designed the garden (Van de Velde Citation1992, 289). The house is well known for its organisation around a central hall. It was the heart of the house: it contained, amongst other things, a piano, an instrument which Maria Sèthe played regularly. The internal organisation of the house was characterised by fluidity: Van de Velde eliminated doors where they were not necessary. The journey through the building was conceived as a circular ‘promenade’, leading from the staircase to an upstairs gallery, with different viewpoints. The internal organisation also favoured a life centred around art, where both husband and wife took part in artistic creation – replacing a traditional hierarchisation of spaces with an emphasis on rooms dedicated to work and to family life (studio, hall, dining room, kitchen).

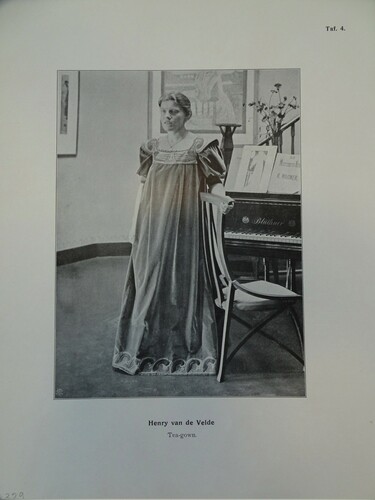

With the Bloemenwerf, scholars have underlined how van de Velde attempted to create a gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art unifying fashion, arts, interior decoration and architecture (Kuenzli Citation2017, 165). Van de Velde designed dresses specifically so that his wife could accessorise the house he built – flowy and comfortable dresses echoing the flexibility and functionality of the house. While it is unclear to what extent Maria Sèthe participated in the design process, a photographic album about women’s fashion published with her foreword identifies her as the maker of the dresses (Van de Velde Citation1900). In his memoirs, van de Velde highlighted the key inspiration Sèthe provided in his ideas for renewing or ‘reforming’ fashion, because she was already making her own dresses and hats before they met (Van de Velde Citation1992, 297). Interestingly, the dresses that she and her husband created are notably more progressive when they are conceived for the domestic environment, as opposed to city or reception dresses. They have a flowing line and are not restricted around the waist (). The dresses that the van de Velde made were supposed to free women from certain constraints, incarnated by a constricted waistline. In them, women could move comfortably and therefore undertake tasks that might not have been available to them otherwise. Maria Sèthe makes the connection between fashion, society and women’s emancipation in her introduction to the album mentioned earlier:

I am convinced [that] women will help bring about a reform in their clothing in an artistic sense and will gain the courage to overturn the laws of fashion. Courage is required. In no other field has conformity so much blunted personality, and nowhere does society exercise such a tyranny as in the realm of fashion. (Van de Velde Citation1900) [my translation]

Figure 4. Album moderner nach Künstler-Entwerfen ausgefürther Damenkleider, with an introduction of Maria Van de Velde, 1900, Dusseldörf: Verlag von Friedr. Wolfrum, pl. 4. ©KBR.

Que la ménagère veille toujours à être sur elle-même d’une propreté irréprochable! Que sa mise du matin soit simple, mais convenable; qu’elle ne se permette jamais de conserver dans l’intérieur une toilette avec laquelle elle rougitait de se montrer! (Destexhe and Marcelle Citation1896, 76)

Conclusion

This article explored the involvement of Belgian male architects and critics of architecture with the domestic sphere, in relationship to the themes of modernity, gender and the interactions of the public and private sphere. Homes were at the heart of crucial social debates on topics such as hygiene and wellbeing, as well as architectural and artistic reforms. Highlighting the importance of the domestic environment to discussions on fin-de-siècle architecture contributes to dismantling the conservative and progressive dichotomy of the female home and the male public sphere.

Contrasting domestic manuals with architecture and interior design magazines has proven useful in uncovering overlapping discourses on homes and domesticity. In these magazines, as well as in Art Nouveau architecture, domestic chores and duties were rendered invisible. Staging, through the concealment of the details of day-to-day housekeeping, and the conscious involvement of a viewer, by presenting interiors mostly as spaces to look at, was a crucial element in the construction of a male perspective on domesticity. Architectural critics used the notion of intimacy to both evoke the ideal home atmosphere, from a men’s point of view, as well as to find new ways to perpetuate its reality.

Looking at the ‘making of domesticity’ results both in interrogating how the values with which it is associated were actively enforced, as well as how they could be subverted. Comfort in the home could be reinterpreted by artistic innovation and instrumentalised for the purpose of women’s emancipation, as seen in the example of Maria Sèthe and Henry van de Velde. Their domestic environment was not a site of conformity but proved to be an ideal space for artistic experimentation, specifically because of the intimacy it fostered.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Apolline Malevez

Apolline Malevez is a Marie Sklodowska-Curie PhD Student in French at Queen's University Belfast. Her research project (entitled: 'Interior Spaces in Belgian Art and Architecture (1880–1914): Domesticity, Materiality and Intimacy') deals with the concepts of domesticity, materiality and intimacy, with a particular emphasis on men's involvement with the domestic sphere, the material culture of artists' homes and the meanings of threshold spaces in the representation of interiors.

Notes

1 Entries for ‘domestique’ in nineteenth-century French dictionaries also refer to the house, housekeeping or the family, see ‘Dictionnaires d’autrefois’ in the database of the ARTFL project (University of Chicago): (“Dictionnaires d’autrefois” Citation2020).

2 Beyond it not being representative, it might also be counterproductive as a conceptual device. Vickery has questioned whether the separate spheres framework holds any analytical power, as it can be roughly be applied to many centuries and cultures, see: (Vickery Citation1993)

3 Jeremy Aynsley has analysed how vision was prioritized above other senses in the spatial display of objects, for example in museums, exhibitions and department stores: (Aynsley Citation2006)

4 Including Art Nouveau architects Victor Horta and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy, important socialist figures such as Emile Vandervelde and information sciences’ pioneer Paul Otlet.

5 They were in all likelihood disregarded by academic critics in favour of more established and/or progressive artistic magazines (such as L’Art Moderne, published between 1881 and 1914).

References

- Adriaenssens, Werner, Thomas Fölh, and Sabine Walter. 2013. Henry van de Velde. Passion, fonction, beauté. Tielt: Editions Lannoo.

- Aynsley, Jeremy. 2006. “Imagined Interiors. Displaying Design for the Domestic Interior in Europe and America, 1850-1950.” In Imagined Interiors: Representing the Domestic Interior since the Renaissance, edited by Jeremy Aynsley, Charlotte Grant, and Harriet McKay, 190–215. London: V&A Publications.

- Balducci, Temma, and Heather Belnap Jensen. 2017. Women, Femininity and Public Space in European Visual Culture, 1789-1914. London: Routledge.

- Balducci, Temma, Heather Belnap Jensen, and Pamela J. Warner, eds. 2010. Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France, 1789–1914. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, VT: Routledge.

- Berry, Francesca. 2006. “Lived Perspectives: The Art of the French Nineteenth-Century Interior.” In Imagined Interiors: Representing the Domestic Interior since the Renaissance, edited by Jeremy Aynsley, Charlotte Grant, and Harriet McKay, 160–83. London: V&A Publications.

- Block, Jane. 1991. “La Maison d’Art. Edmond Picard’s Asylum of Beauty.” In Irréalisme et Art Moderne. Mélanges Philippe Roberts-Jones, edited by Michel Draguet, 145–57. Brussels: Université Libre de Bruxelles.

- Brogniez, Laurence. 2018. “De l’intérieur d’artiste à l’intérieur artiste: l’atelier d’artiste, entre pierre et papier, dans le Bruxelles fin de siècle.” Dix-Neuf 22 (3–4): 245–61.

- Brown, Kathryn. 2012. Women Readers in French Painting 1870-1890: A Space for the Imagination. Aldershot [etc.]: Ashgate.

- Cambridge English Dictionary. 2020. “Domestic.” Cambridge English Dictionary. 2020. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/domestic.

- Cheysson. 1904. “Le Foyer, aujourd’hui, autrefois.” Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, October, 339–41.

- Clapham Lander, H. 1904. “Les Avantages des habitations coopératives.” Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, February, 45–51.

- Destexhe, S., and M. Marcelle. 1896. Economie domestique, hygiène, alimentation et horticulture. Liège: H. Dessain.

- Detienne, Louise, and Zélie Voituron-Liénard. 1901. Cours complet d’économie domestique et d’alimentation. Pour l’enseignement moyen, les écoles normales primaires et les écoles ménagères. Namur: A. Wesmael-Charlier.

- “Dictionnaires d’autrefois.”. 2020. 2020. https://artflsrv03.uchicago.edu/philologic4/publicdicos/query?report=bibliography&head=domestique&start=1&end=14.

- Didier, Charles. 1904. “La Maison de demain. Un projet du Cottage.” Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, August, 296–300.

- Dr N., Ensch. 1903. “Le Retour aux champs.” Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, July, 2–5.

- Draguet, Michel. 2018. Fernand Khnopff le maître de l’énigme. Paris: Petit Palais. Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris.

- Dupont, Paul. 1908. “Les Habitations ouvrières.” Le Home: Revue mensuelle illustrée de l’habitation et du foyer, May, 3–5.

- Fraiman, Susan. 2017. Extreme Domesticity: A View from the Margins. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Heim. 1910. “Mon Home.” Le Home: Revue mensuelle illustrée de l’habitation et du foyer, April, 11–13.

- Heymans, Vincent. 2018. “Les Intérieurs historiques. Là où bat le coeur du patrimoine.” Bruxelles Patrimoines (29 (December)): 6–23.

- Kuenzli, Katherine M. 2017. The Nabis and Intimate Modernism: Painting and the Decorative at the Fin-de-Siècle. London: Routledge.

- “Les Domestiques.”. 1904. Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, April, 133–38.

- “Les Pages de la Femme.”. 1913. Le Home, no. 1 (January).

- Marcus, Sharon. 1999. Apartment Stories: City and Home in Nineteenth-Century Paris and London. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Moran, Claire. 2018. “Fernand Khnopff and the Aesthetics of Intimacy.” Dix-Neuf 22 (3-4): 204–221.

- “Notre Programe.”. 1903. Le Cottage: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, June.

- Perrot, Michelle. 1999. Histoire de la vie privée. De la Révolution à la Grande Guerre. Histoire de la vie privée. Paris: Ed. du Seuil.

- Reed, Christopher. 1996. Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Rosner, Victoria. 2005. Modernism and the Architecture of Private Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Scotford, Martha. 1994. “Toward an Expanded View of Women in Graphic Design: Messy History vs. Neat History.” Visible Language 28 (4): 367–87.

- Silverman, Debora. 1994. L’Art nouveau en France : Politique, psychologie et style fin de siècle. Paris: Flammarion.

- Singletary, Suzanne. 2008. “Le Chez Soi. Men ‘At Home’ in Impressionist Interiors.” In Impressionist Interiors, edited by Janice MacLean, 31–51. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland.

- Société centrale d’architecture de Belgique. 1891. “Plate 21.” L’Emulation, no. 12 (December).

- Société centrale d’architecture de Belgique. 1892. “Plate 44-45.” L’Emulation, no. 12 (December).

- Société centrale d’architecture de Belgique. 1896. “Plate 50-52.” L’Emulation, no. 6 (June).

- Van de Velde, Maria. 1900. Album Moderner, Nach Künstlerentwürfen Ausgeführter Damenkleider. Dusseldorf; Krefeld: Verlag von Friedr. Wolfrum; J.B. Klein’sche Buchdruckerei, M. Buscher.

- Van de Velde, Henry. 1992. Récit de ma vie: Anvers, Bruxelles, Paris, Berlin I. 1863-1900. Edited by Anne Van Loo. Bruxelles; Paris: Versa; Flammarion.

- Vickery, Amanda. 1993. “Golden Age to Separate Spheres? A Review of the Categories and Chronology of English Women’s History.” The Historical Journal 36 (2): 383–414.

- Wolff, Janet. 2008. “Gender and the Haunting of Cities (or, the Retirement of the Flâneur).” In The Invisible Flaneuse? Gender, Public Space and Visual Culture in Nineteenth Century Paris, edited by Aruna D’Souza, and Tom McDonough, 18–31. Manchester: Manchester University Press.