ABSTRACT

Building on a tantalizing footnote by Anne-Marie Christin, my article analyses the illustrated editions of André Gide's Le Voyage d'Urien in tandem. It looks at the 1893 edition, a collaboration between Gide and Maurice Denis, and the 1928 edition, featuring illustrations by Alfred Latour. I explore the impact the two sets of illustrations might have on our reading of Urien's travels, demonstrating the potential these divergent visuals have to (re)shape our perceptions of the narrative's central journey. The co-existence of these editions also helps us ask how the illustrations add to and even disrupt conceptions of the reading process.

KEYWORDS:

In 1984, an article entitled ‘Un livre double: Le Voyage d’Urien par André Gide et Maurice Denis (Citation1893)’ appeared in Romantisme. In this article, Anne-Marie Christin dissects the collaboration of the writer and the artist on the original 1893 edition published by the Librairie de l’Art Indépendant, uncovering what Mitchell (Citation1986) will go on to decry as the paragonal struggle for dominance that can occur between text and image.Footnote1 Gide and Denis, at the former’s behest, are given equal billing on the work’s title page, and thus the book might be seen as something of a case study for artist and writer collaboration, although later editions will move, perhaps unsurprisingly, to drop the costly illustrations (which comprise thirty lithographs in total). In 1928, however, the only other illustrated edition of Le Voyage d’Urien appears with the Maastricht-based Halcyon Press, featuring striking original illustrations by the French painter Alfred Latour (woodcuts, with initials by Alphonse Stols). In the aforementioned article, Christin notes the work’s potential significance in publishing history (indeed, it might even be said to prefigure the rise of the livre d’artiste in the twentieth century [Brown Citation2013]). She also suggests that studying the text’s various editions, or ‘ces variantes’, would bring an ‘éclairage très intéressant au Voyage’ (Citation1984, 74). My article therefore proposes to do just that, in part: to shed light on the impact the above two sets of illustrations might have on our reading of Urien’s travels, while also demonstrating the power of these divergent visuals to (re)shape our perceptions of the key moments of the narrative’s central journey. In Le Voyage d’Urien, the envoi pointedly tells us we have never left ‘la chambre de nos pensées’ (2009, 230). Valérie Michelet Jacquod has consequently argued that Le Voyage d’Urien, in all its self-awareness, functions as a ‘voyage dans l’écriture’ (Citation2008, 425). However, I extend this to suggest that Gide’s narrative, all the more so when bolstered by the illustrations of Denis or Latour, ultimately amounts to a journey that explores reading itself. Frédéric Canovas has previously proposed that ‘book illustration can be construed, for better or worse, as a form of reading and interpretation and, in the case of Gide’s Voyage d’Urien, as a form of conscious misreading and calculated misinterpretation’ (Citation2009, 122). Instead, I shall pursue a line of inquiry where Denis’s efforts are not viewed as deliberately recalcitrant but are interpreted more so as products of an assertive taking of liberties on the part of the illustrator, which is wholly encouraged by Gide – and therefore certainly not in wilful defiance of the latter, nor their future readers. The co-existence of the two illustrated editions of Le Voyage d’Urien also means that we can ask ourselves to what extent do the illustrated versions of this text add to and even disrupt any conception of the reading process? Might the mysterious figure who is found encased in a block of ice towards the culmination of Urien’s journey, a man clutching a blank page, even be seen to represent the illustrator at work as much as the writer? And how might the discussions prompted by Gide, Denis and Latour around Le Voyage d’Urien shed light on the role of book illustration – and that of the reader – more generally?

Gide’s book focuses on Urien, an initially solitary figure whose vivid dream transports him from his bedchamber on a quest-like journey through a variety of seascapes and landscapes, accompanied by a crew of sailors.Footnote2 I have written elsewhere (Geary Keohane Citation2013) about the artfulness involved in Gide’s slippery and yet largely overlooked text. In a later interview with Jean Amrouche (Marty Citation1987, 160–161), Gide would dismiss this early work as youthful experimentation on his part, but to see it solely in this vein would be to take from the innovativeness that characterizes the extensive collaboration between Gide and Denis. Christin’s assertion that the original collaboration between Gide and Denis constitutes a ‘livre double’ is an especially tantalizing one. The expression naturally suggests duality, doubling up (repetition and overlap) and coupling up (close collaboration) – but it also hints at the potentially more disruptive dédoublement, a splitting into two parts. Christin mentions the term dédoublement only once, however, in reference to Gide’s insistence that Denis be given a co-author credit on the book’s title page:

Commentant ce dédoublement de l’auteur, dont il avait pris lui-même l’initiative, Gide écrivait à Denis au moment où ils recevaient les premières épreuves de l’ouvrage: ‘Cela ne vous plaît-il pas plus que “illustrations de etc.”? Car enfin c’est une collaboration, et ce mot d’illustrations semble indiquer une subordination de la peinture à la littérature qui me scandalise.’ (Christin Citation1984, 74)

We might say that there are two sections through the substance of the world: the longitudinal section of painting and the transverse section of certain graphic works. The longitudinal section seems representational – it somehow contains things; the transverse section seems symbolic – it contains signs. Or is it only in our reading that we place the pages horizontally before us? (Citation1996, 82, emphasis in original)

The symbiotic relationship between text and image in an illustrated book is perhaps a given, but it is nonetheless useful to be reminded of our continuing dependency on textual referents when encountering an image. In his 1964 essay ‘Rhétorique de l’image’, Roland Barthes writes: ‘il n’est pas très juste de parler d’une civilisation de l’image: nous sommes encore et plus que jamais une civilisation de l’écriture’ (Citation1964, 43), a statement that will be pithily echoed by Michel Butor in his 1969 text Les Mots dans la peinture: ‘notre vision n’est jamais pure vision’ (Citation1969, 5). The inevitability of the verbal should also be set into a wider context, one where the purported divide between text and image is constantly – and perhaps even baselessly – rehearsed, as Mitchell notes:

The history of culture is in part the story of a protracted struggle for dominance between pictorial and linguistic signs […] At some moments this struggle seems to settle into a relationship of free exchange along open borders; at other times (as in Lessing’s Laocoön) the borders are closed and a separate peace is declared. Among the most interesting and complex versions of this struggle is what might be called the relationship of subversion, in which language or imagery looks into its own heart and finds lurking there its opposite number. (Citation1986, 43)

[T]he paragone or debate of poetry and painting is never just a contest between two kinds of signs, but a struggle between body and soul, world and mind, nature and culture. The tendency of poetry and painting to mobilize these hosts of opposing values is perhaps becoming more evident to us now just because we live in a world where it seems a bit odd to think of the realm of aesthetic signs as divided between poetry and painting. (Citation1986, 49)

With Denis’s observations about illustration, we thus move beyond any initial concern about the dédoublement and compartmentalizing of the creative forces behind the work to the idea of multiplying possibilities for their reader – collaboration not just as the meting out of clearly delimited roles, but as creating something that can be appreciated as indivisibly greater than the sum of its parts. In a letter to Gide dated 11 August 1892, as their collaboration slowly progresses, Denis informs his collaborator of the creative process he intends to adopt while engaging with Gide’s drafts: ‘je me laisserai aller […] à la plus libre fantaisie’ (Citation1957, 106). As readers of the product of their collaboration, then, wherein individual flights of fancy have been actively acknowledged and encouraged as a fundamental part of the joint creative process, we are privy to the artistic journeys of both Gide and Denis; in this way, their individual perspectives combined can only enhance our own engagement with the work.

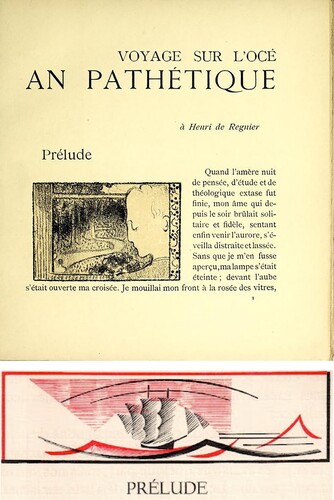

Since Denis, in Définition du néo-traditionnisme, theorizes illustration in a clear-sighted way it is also helpful to take on board some of his points when considering the 1928 Latour contribution. Of course, it is hardly a surprise that the radically different styles of Denis and Latour themselves have a significant impact on the way we might approach Gide’s text. shows their contributions to the opening page of the Prélude section of ‘Voyage sur l’Océan Pathétique’. Denis’s Post-Impressionist Nabi style pays homage to the oneiric qualities of Gide’s text, which, as we have noted, recounts a lengthy lucid dream; delicate curvilinear forms reign supreme across all Denis’s illustrations for the book. The two-dimensional vegetal border on the right-hand side of this particular illustration, a feature used repeatedly throughout the text by Denis, underscores the purely decorative purpose Denis claims for illustration alongside the wider visual narrative created by the ensemble of illustrations headed up by this example. Latour’s minimalist modernist style is in general much starker.Footnote6 His illustration for the opening page of the text showcases the advantage of using a bright attention-grabbing colour, setting it apart from the text in a much more pronounced way than Denis’s illustration for this section. This visual impact is furthered by the three-dimensional effect achieved by the combination of red and black bordering surrounding the image, which injects dynamism into the illustration, so that it almost appears to leap off the page. In relation to Denis’s opening illustration, which replaces the usual embellished initial with which a text at this time might be expected to start, Christin writes: ‘L’absence de lettre oblige le regard à prendre en compte le voisinage de la figure et du texte en tant que tel, et à s’interroger simultanément sur un voir et sur une lecture […]’ (Citation1984, 78). Whereas the typical initial serves to pitch the reader immediately into a reading of the text at hand, the illustration that sets into motion the Prélude sees our journey start off somewhat less assuredly, as we oscillate between this image and the first line of text. As Barthes writes, our approach to reading will always hinge on the following question, which again utilizes the vocabulary of doubleness: ‘L’image double-t-elle certaines informations du texte […] ou le texte ajoute-t-il une information inédite à l’image?’ (Citation1964, 43) It might therefore be argued that the reader themselves experiences a dédoublement of sorts when faced with the illustration that supplants the initial – a dividing of our attention and focus that can be said to mirror Urien’s shift from bedchamber to boat in the opening pages of the text. For Christin, there are nonetheless some advantages to this creative decision: ‘L’idée d’ouvrir le texte, en lieu et place d’une lettrine, par une image initiale, avoisinant comme elle l’écriture et s’inscrivant dans son corps, permettait de donner à l’illustration une valeur tout à fait exceptionnelle de plénitude et d’ambiguïté’ (Citation1984, 78). Whilst I would tend to echo this perspective, it also might be seen as the illustration asserting itself in spite of the text, offering an alternative point de départ for a simultaneous journey that takes us from one illustration to the next. Although Christin continues to highlight the jarring nature of this decision to replace an initial with an image, she does concede that it has the potential to boost the role of the illustration in new and unexpected ways:

l’image ne feint plus d’appartenir au texte, pourtant elle reste soumise à lui, en s’insérant dans les données structurelles qui sont propres à celui-ci […]. Mais d’autre part, l’infidélité éventuelle […] des motifs de cette image par rapport au texte qu’elle accompagne impose à ce texte un éclairage tout à fait nouveau et déroutant. (Citation1984, 78)

Pour détourner le lecteur de tout soupçon de réalisme, n’était-il pas indiqué de recourir alors à une illustration qui serait elle-même doublement désancrée, et par rapport au monde réel, et par rapport au texte, ne copiant ni l’un ni l’autre mais s’affirmant comme l’expression sur le plan visuel de la même émotion que celle que le récit suggérait? (Citation2006, 10)

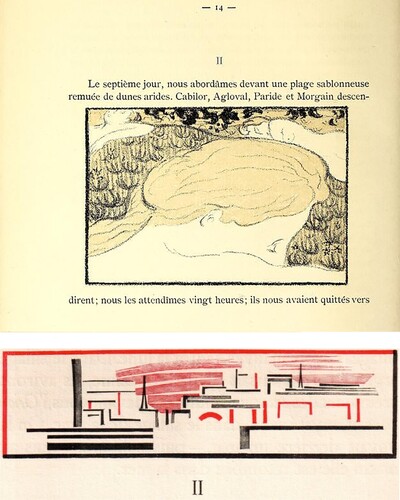

The opening page of Section II similarly showcases the diverging approaches of Denis and Latour (). In the case of Denis’s illustration, a group of naked women languishing in a marine setting, almost obscured by the foregrounded head of a bashful member of their company, contrasts with Latour’s bustling townscape viewed from afar: ‘C’est alors qu’elle nous apparut, cette prodigieuse cité, non loin de nous, dans une immense plaine […]. Au-dessus de la ville flottaient des brouillards en nuages que déchiraient les minarets pointus’ (Citation2009, 189). Having been warned by one of the sailors, Paride, that these women are, in fact, sirens (Citation2009, 188), the remaining crew subsequently learns that the town these sailors appear to happen upon is but a mirage conjured by the sirens’ enchanting songs (Citation2009, 190). Latour then sets up the reader to share in this mirage before it is revealed as such, and therefore to fall into the trap set by the sirens in the text (drawing on illustration’s ludic potential). Denis, however, allows the reader to see the sirens at rest, and we are thus not made unwitting victims of this illusion. These very different approaches show, in Latour’s case, illustration’s capacity to aid and abet the text and, in the Denis example, to act as an occasionally defiant corrective to the vagaries of the narrative.

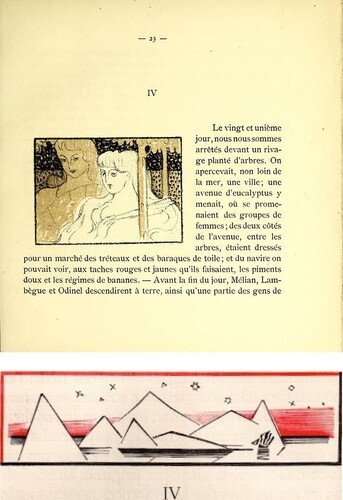

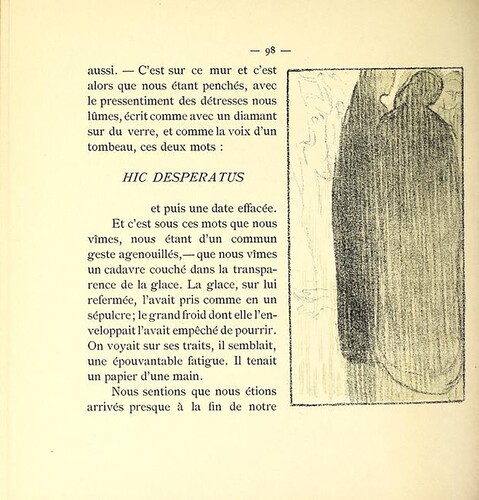

The contrast we see here is later reflected in the illustrations for the opening page of Section IV (). Denis focuses on presenting an image of the women who are mentioned in the text as walking on the shoreline (whose mirror-like pairing would seem to foreshadow the entwined figures that appear on the later Hic desperatus page, as we shall see), whereas Latour begins the section with a stark landscape in his pared-back scheme of black, white and red (black, white and blue are also to be found in other vignettes for this edition). At each turn, Denis populates his illustrations with the characters alluded to in the text, whereas Latour keeps the reader at a distance from the narrative with his illustrations, which, largely focused on the boat itself, often tend to pitch the reader’s gaze into the middle distance. Denis invites us into Gide’s text with a selection of intimate illustrations depicting the folds of human bodies, for instance, whereas Latour consistently keeps us at bay, such as in this illustration where the boat manned by the main characters is but a blot near the horizon. These opposing dynamics are testament to the power of illustration to involve us and draw us in but, conversely, they also make clear to us the extent to which illustrations can tantalize us and keep us at one remove from proceedings, omniscient observers whose all-seeing eye nonetheless is forced to depend on the text to supplement the overview offered by the illustration. While Barthes and Butor have strenuously argued that the visual cannot exist in a non-verbal vacuum, as mentioned earlier, illustration’s inherent power may well be that it precisely is what keeps driving us and rerouting us towards the text to unlock further detail and clarification. Illustration is, to revisit Denis’s insistence that the latter be ‘sans servitude du texte’ (Citation1920, 11), something which instead can equally be said to employ the text to do its bidding, setting up the text as a means of decoding it rather than the other way round, as we might traditionally expect.

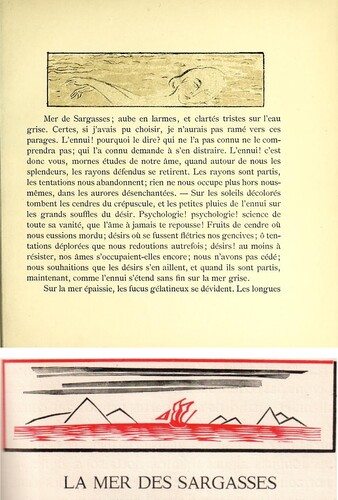

The ‘La Mer des Sargasses’ chapter is another notable example where both artists offer comparable illustrations that encompass entirely different approaches (). Denis’s illustration depicts a figure peacefully bobbing in the waves, echoing the undulations that prevail across the ensemble of his lithographs, whereas once again Latour’s vignette shows us the ship from a considerable distance, making its way across a new seascape, the furthest point to which the sailors shall travel. The contrast here perhaps further underlines Denis’s inventiveness – instead of opening the section with a general illustration of the sailors’ progress, as Latour does, we appear to be ushered immediately into the action of the chapter. Yet we will scan many pages of text before arriving at the scene potentially alluded to in this illustration, Urien’s memory of his fellow sailor Morgain at an earlier location being the primary contender:

L’eau de la mer devint peu à peu si limpide que les roches du fond parurent. Songeant à tout l’ennui d’hier, aux bains parfumés de jadis, je regardais la plaine sous-marine; je me souvenais que Morgain, aux jardins d’Haïatalnefus, était descendu sous ses ondes […] (2009, 214–215)

The Denis illustration that accompanies the discovery of the figure encased in a block of ice (see ) offers a crucial insight into the culmination of the sailors’ journey. In Gide’s text, the sailors quickly come to discover that this figure is clutching a blank page in his hands. I have previously suggested that this character represents the writer figure who is grappling with their process and perhaps struggling to create (and therefore reflective of Gide’s own state at the time of writing) (2013, 75). However, I think it might also be argued that this figure can equally be said to represent the illustrator awaiting or perhaps even defying instruction, the blank page that both parties might appropriate acting as a metaphor for the endless possibilities of collaboration. Denis’s illustration accompanying this episode shows two figures that are shadowy and turn away from the reader; although in conversation with one another, they almost appear to be a single entity. While Christin sees this pair as potentially representing Gide and Denis, she describes this in fraternal terms: ‘Ce sont ces frères […] dont la silhouette sombre est, fait unique dans le volume, repoussée à droite du texte où s’inscrit le “hic desperatus” fatal’ (Citation1984, 87). However, I would argue that this illustration comes across as far more ambivalent: the illustration depicts the way the writer and illustrator of the text strike a balance between being at once a double act – collaborators – and, suggestive of dédoublement, two independent operators working in two different mediums. In their introduction to the Gide-Denis correspondence, Masson and Schäfer state: ‘Le surprenant, c’est de voir Gide se lancer dans cette collaboration alors qu’il n’a pas terminé la première des trois parties de son texte. Même s’il peut indiquer à Denis les grandes lignes de son livre, il n’en connaît pas encore la portée finale’ (Citation2006, 13). However, can we really be surprised at the open-ended nature of this collaboration, given the willingness of both Gide and Denis to inform each other’s process by granting both space and freedom to their collaborator? Moreover, we must not lose sight of the fact that Denis accompanies Gide not only as his illustrator but as an intent reader, watchful as Gide’s writing progresses. This of course comes with its own drawbacks, as Denis notes, in a letter dated 2 September 1892: ‘J’ai bien peur de ne pouvoir exprimer toutes les choses que j’ai senties à la lecture de votre Voyage’ (Citation2006, 53). Denis’s fear that he will not have adequately expressed his own reactions through the work he produces for Gide is something Gide might be seen to address obliquely in the 1896 preface to the second edition of Le Voyage d’Urien (which, as previously noted, does not contain Denis’s illustrations). Gide writes eloquently about the way an emotion, once born, cannot die away, but will instead undertake a journey of transformation: ‘[i]ci paysage, là geste, plus loin onde, plus loin harmonie, enfin œuvre d’art et poème’ (Citation2009, 234). The suggestion here, particularly when it comes to ‘enfin œuvre d’art et poème’, is that the relationship between text and image, when tasked when conveying emotion, is one of mutual ease, and one of considerable fluidity. It therefore might be said that even though Denis’s illustrations do not feature in this subsequent edition, the porous spirit of the latter’s collaboration with Gide very much lives on in Gide’s new preface to the text.

In his first letter to Denis regarding their then upcoming collaboration, Gide states: ‘mon texte ne sera vraiment définitif que lorsque tout le bouquin sera complètement achevé, car toutes les parties doivent influer plus ou moins les unes sur les autres. Pourtant, je ne pense pas le modifier beaucoup, car ce que je vous livre je l’ai déjà beaucoup travaillé (Citation1957, 104). The tentative undertones to this handover – and the extent to which this act might itself function as a creative impetus for the writer at work – would later find an echo in what Gide writes (albeit in a much more assured fashion) in the highly self-aware foreword to his 1895 text Paludes:

Avant d’expliquer aux autres mon livre, j’attends que d’autres me l’expliquent. Vouloir l’expliquer d’abord c’est en restreindre aussitôt le sens […]. Et ce qui surtout m’y intéresse, c’est ce que j’y ai mis sans le savoir, – cette part d’inconscient […]. Un livre est toujours une collaboration, et tant plus le livre vaut-il, que plus la part du scribe y est petite […]. (Citation2009, 259)

In this article we have looked at collaboration, both in practice and in theory, in terms of Gide and his illustrators, but we have also taken into consideration the part the reader might choose or indeed be invited to play. As the above foreword attests, the reader’s role in imbuing the finished product with meaning is never far from Gide’s mind; indeed, the envoi of Le Voyage d’Urien pointedly reminds us of the centrality of the reader by reducing the preceding narrative to this simple act: ‘Nous lisions’ (Citation2009, 230). The ‘nous’ here would seem to suggest that we, alongside Urien, are very much foregrounded in this act. In this article, we have also seen that both Gide and Denis, through their collaboration, invite us to revisit our conceptualizations of painting and illustration more generally. While there can be no doubt that this joint work constitutes a particularly rich contribution to book illustration in the nineteenth century, its timelessness is very much rooted in the way it boldly invites reflection on illustration’s wider capacity to assert itself, that is, to find and take up space for itself, and to renegotiate the dynamics of text-image relations. This in turn paves the way for Denis’s contribution to create a model of sorts for a wider discussion of the role of illustration, whether the enterprise be undertaken by a different artist, such as Latour for the same text thirty-five years later, or even dispensed with entirely, as would occur in the subsequent publishing history of Le Voyage d’Urien.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Geary Keohane

Elizabeth Geary Keohane is a Lecturer in French at the University of Glasgow. Her undergraduate and postgraduate studies were undertaken at Trinity College Dublin, with a stint at Université de Paris 7. She mainly works on travel writing and text-image studies, especially in a late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century context. Her research has been published in journals including French Studies and Studies in Travel Writing. She is currently working on a project looking at Gide’s influence in relation to Scottish literature, which is funded by the Carnegie Trust.

Notes

1 Barbara Wright and Anne-Marie Christin were friends over many decades.

2 See Ursula Franklin, who speaks about the model of ‘a questing voyage’ (Citation1979, 260).

3 The collaboration was Gide’s suggestion, made through his publisher, as Christin notes (Citation1984, 74).

4 Patricia Mainardi’s Citation1993 study The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic offers an extensive insight into the both the power and decline of the Salon, shedding light on the state’s abandonment of the annual Salon model in 1880, and the subsequent Triennale, held in 1883, which was meant to replace this system.

5 This is similar to the way ekphrasis frequently tries to disengage itself from the work of art that inspires it, an argument I have previously made in relation to Henri Michaux’s Magritte-inspired ekphrastic work (Geary Keohane Citation2010).

6 The boat and stark seascapes that predominate in Latour’s woodcuts for the 1928 edition of Le Voyage d’Urien are a much more restrained vision of the marine world than what we see in his 1921 work, Mer et coquillages, although a recognizable continuity of style remains.

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1964. “Rhétorique de l’image.” Communications 4: 40–51. doi:10.3406/comm.1964.1027.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1996. “Painting and the Graphic Arts.” In Selected Writings: 1913–1926. Vol. 2. 4 vols., edited by Marcus Bullock, and Michael W. Jennings, 82. Cambridge; Mass.: Belknap Press.

- Brown, Kathryn, ed. 2013. The Art Book Tradition in Twentieth-Century Europe. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Butor, Michel. 1969. Les Mots dans la peinture. Geneva: Skira.

- Canovas, Frédéric. 1997. “Urien l’innommable, Gide l’insaisissable. Les noces difficiles du texte et de l’image.” Word & Image 13 (1): 58–68. doi:10.1080/02666286.1997.10434267.

- Canovas, Frédéric. 2009. “From Illustration to Decoration: Maurice Denis’s Illustrations for Paul Verlaine and André Gide.” In Models of Collaboration in Nineteenth-Century French Literature: Several Authors, One Pen, edited by Seth Whidden, 121–135. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Christin, Anne-Marie. 1984. “Un livre double: Le Voyage d’Urien par André Gide et Maurice Denis (1893).” Romantisme 43: 73–90. doi:10.3406/roman.1984.5447.

- Denis, Maurice. 1920. Théories 1890-1910: Du symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique. Paris: Rouart.

- Denis, Maurice. 1957. Journal (1884–1904). Vol. 1. 3 vols. Paris: La Colombe, 1957–1959.

- Franklin, Ursula. 1979. “Urien’s Anti-Quest: Gide’s Parting Statement to Symbolism.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 7 (3–4): 258–271.

- Geary Keohane, Elizabeth. 2010. “Ekphrasis and the Creative Process in Henri Michaux’s En rêvant à partir de peintures énigmatiques.” French Studies 64 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1093/fs/knq032.

- Geary Keohane, Elizabeth. 2013. “A Return Trip in the Writer’s Imagination: Gide’s Le Voyage d’Urien (1893).” In Aller(s)-Retour(s): Nineteenth-Century France in Motion, edited by Loïc Guyon, and Andrew Watts, 62–78. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Gide, André. 1893. Le Voyage d’Urien. Paris: Librairie de l’Art Indépendant.

- Gide, André. 1928. Le Voyage d’Urien. Maastricht: Halcyon.

- Gide, André, and Maurice Denis. 2006. Correspondance 1892–1945, edited by Pierre Masson, and Carina Schäfer. Paris: Gallimard.

- Gide, André. 2009. Romans et récits. Œuvres lyriques et dramatiques, edited by Pierre Masson, Jean Claude, Alain Goulet, David H. Walker, and Jean-Michel Wittmann. Paris: Gallimard.

- Mainardi, Patricia. 1993. The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marty, Éric. 1987. André Gide – Qui êtes-vous? Lyon: La Manufacture.

- Michelet Jacquod, Valérie. 2008. Le Roman symboliste. Un art de l’“extrême conscience”. Geneva: Droz.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.