ABSTRACT

Grounded in Zola’s art criticism, this article analyses for the first time his writing on Fromentin over the decade 1866–76. It explores the diverse reasons for a hostility that is inseparable from a wider frame of reference in which Orientalism is perceived as emblematic of a Romantic aesthetic opposed by Zola. Paradoxically, however, Zola’s engagement with Fromentin’s Les Maîtres d’autrefois, opposed to modernist innovation, coincides with his own increasing disenchantment with Impressionism. His simultaneous re-evaluation of the Old Masters allows us to discern shared pictorial priorities which bring Zola and Fromentin into the same critical frame.

Across Émile Zola’s voluminous literary criticism and writing on the visual arts, references to Eugène Fromentin (1820–1876) are few and far between, although the latter’s virtually unique contemporary profile as author and artist might have qualified him for inclusion in both. Some are merely incidental, such as summative reports on the auctions of various private collections which included a number of Fromentin’s paintings, the prices for which were noted by Zola with barely-concealed astonishment.Footnote1 Equally revealing of his attitude towards the painter’s popularity and commercial success is the short piece he devoted to the posthumous sale of the contents of Fromentin’s studio, extended over four days (30 January–3 February 1877), which raised ‘la somme énorme’ of 433,725 francs: ‘de simples dessins sont montés à mille francs. On s’arrachait les moindres bouts de toile’ (Zola Citation2021, 660). The most substantial mention, however, is to be found in a text published a couple of months before Fromentin’s death on 27 August 1876. This appeared in the June issue of Le Messager de l’Europe (Vestnik Evropy), the St Petersburg periodical to which Zola contributed between 1875 and 1879. Occasioned by the Salon of 1876 as well as the second Impressionist exhibition, thereby explaining its title of ‘Deux expositions d’art au mois de mai’, Zola’s long article offered his Russian readers an overview of recent developments in French painting. It is here that he writes of Fromentin as ‘un peintre qui jouit d’une grande renommée’ (336) and ‘un des maîtres de nos jeunes peintres […] un homme remarquable qui a remporté de beaux succès. Il s’est fait une spécialité des Arabes’ (330). But he goes on to say of Fromentin’s pictures shown at that year’s Salon – Le Nil (Haute-Égypte) (Cairo: Musée Mahmoud Khalil) and Souvenir d’Esneh (Haute-Égypte) (Paris: Musée d’Orsay) – that ‘c’est un art délicat auquel on ne peut reprocher que de nous représenter un Orient faux, adapté au goût bourgeois; son Orient est banal et ses Arabes sont peints de chic’.Footnote2 And this denigration of Fromentin’s pictorial talents is immediately followed by a decidedly lukewarm reference to his also being ‘un écrivain non dépourvu de mérite’, the double negative exacerbated in an allusion to his Dominique being ‘un roman, à la vérité médiocre’, which, given the specific focus of Zola’s review, seems almost gratuitously hostile. The aim of the present essay, with recourse to the ‘interconnections’ of a critical context in which the particular case of Fromentin has to be inserted, is to explore the imbricated frames of such opposition. But it will also suggest, in its conclusion, the ways in which a reframing of perspectives illuminates those paradoxically shared by Fromentin and Zola himself.

One of Zola’s very first remarks about Fromentin, in L’Événement of 20 May 1866, sets the tone. To describe Fromentin as ‘le dieu du jour’ (Zola Citation2021, 167) was as ironic as lauding ‘les quatre génies de la France’ hyperbolically celebrated at the Universal Exhibition of 1867 and whose inflated reputations Zola (528–540) could not therefore resist the temptation to demolish: Ernest Meissonier (1815–91), Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) and Théodore Rousseau (1812–67). For it was also in 1866 that Zola formulated a rule of thumb positing an inverse relationship between creative originality and artists catering for the tastes of a philistine public: ‘c’est que l’admiration de la foule est toujours en raison indirecte du génie individuel’ (162). That Fromentin’s paintings were fashionable in the 1860s is not in doubt. No less open to Zola’s pejorative commentary were his social status and political affiliations, as detailed in Barbara Wright’s magisterial study of his life and work (Citation2000). By the time he came to Zola’s attention, Fromentin was an establishment figure. He had made his Salon debut in 1847 with two of his three pictures on display heralding the Orientalist manner on which his fame was to rest: Mosquée près d’Alger (location unknown); and Vue prise dans les Gorges de la Chiffa (province d’Alger) (Private Collection). Two years later all five of his canvasses were admitted and the award of a Second Class Medal exempted him from in future having to submit his paintings to the admissions jury. During the next decade, in every year he sent works to the Salon; these were therefore all available for viewing. At the official exhibition of 1850, postponed from its traditional May date until December (and designated as the Salon of 1850–51 because of the turmoil following the two 1848 revolutions), he had eleven paintings on show. And his profile was consecrated by the Salon of 1859, the ‘Salon-roi dans l’œuvre de Fromentin’ as noted by his first admiring biographer (Gonse Citation1881, 60), at which his five paintings were greeted with acclaim. In addition to receiving a First Class Medal, he was nominated for the first rung of the Légion d’Honneur. In 1863, while Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and paintings by Cézanne, Pissarro, Whistler and Fantin-Latour were relegated to the Salon des Refusés, Fromentin’s Chasse au faucon: la curée (Paris: Musée d’Orsay) was purchased by the State for 7000 francs and hung in the Luxembourg, the ‘waiting-room’ for the work of living artists in anticipation of being posthumously transferred to the Louvre. And a second Orientalist submission to the official exhibition, Fauconnier arabe (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum) (), was snapped up by a private buyer. What Wright describes as his initially ‘apolitical’ stance (Citation2000, 205–206) does not seem to have survived his entry at this same moment into the Bonapartist circle of Princesse Mathilde and Napoléon III’s invitations to Compiègne. These brought him into contact with the most influential of the Second Empire’s arbiters of public taste, starting with Comte Nieuwerkerke, given the aptly-named title of Surintendant des beaux-arts in 1863, who made a point of personally making the award when Fromentin was promoted to the rank of Officier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1869. This was also the year that he figured on the imperial guest-list to attend the opening of the Suez Canal, alongside art critics as prominent, and as unrelentingly conservative, as Charles Blanc (1813–82). It was not by chance that Fromentin was a member, alongside other approved painters like Meissonier and Gérôme, of the committee charged in 1866, by the Marquis de Chennevières (Nieuwerkerke’s protégé and, under the Third Republic, successor), with considering reforms to Salon regulations. And nor is it by chance that Blanc and Chennevières, two crucially important administrators of the contemporary fine arts, should be the repeated targets of Zola’s polemical journalism during the period 1866–75.

Leaving aside the wider political context in which Zola’s writing in the opposition press made it inevitable that artists associated with Napoléon III’s regime were thereby implicitly complicitous, with what he termed the complementary ‘dictatorship’ of the École des Beaux-Arts, the particular instance which brought Fromentin within Zola’s ‘sights’ was the painter’s membership of the Salon jury of 1866, ‘truly representative of its bemedalled and decorated constituency’ (Mainardi Citation1987, 130). While artists came and went (elected or not by their peers), Fromentin sat on the admissions jury from 1864 until his death twelve years later, after which it was lamented in some quarters that ‘le jury du Salon a perdu en lui un des organes les plus actifs et les plus éclairés’ (Gonse Citation1881, 104). This was certainly not Zola’s view; he did not even acknowledge Fromentin’s partial redemption in being one of only two members of the 1872 jury, on which he served as vice-president, to vote for Gustave Courbet’s admission notwithstanding his association with the Commune. For the jury system itself, from Zola’s perspective, was so pernicious that unquestioning adherence to it, such as Fromentin’s, simply perpetuated the reach of institutional structures designed to exert State control of artistic expression. His survey of the Salon of 1866 is prefaced by a ferocious ad hominem attack on the prejudices and regressive criteria of a jury which had rejected Manet’s two submissions, Le Joueur de fifre (Paris: Musée d’Orsay) and L’Acteur tragique (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art). Of its twenty-one members who were artists in their own right (leaving aside the other seven government appointments), only Camille Corot (1796–1875) and Charles-François Daubigny (1817–78) were spared Zola’s fury. As well as being damned by association (as a ‘grand ami’ of Alexandre Bida (1823–95), deemed to be totally unqualified to judge the work of others), Fromentin is primarily attacked through his paintings, having returned from North Africa with ‘de délicieux sujets de pendule’: ‘ses Bédouins sont d’un propre à manger dans leurs assiettes’; and Zola extends the metaphor by categorising Fromentin as one of those ‘artistes suaves qui comprennent la poésie, qui déjeunent d’un rêve et qui dînent d’un songe, [qui] ont de saints effrois à la vue des toiles leur rappelant la nature, qu’ils ont déclarée trop sale pour eux’ (Zola Citation2021, 140). This antipathy feeds into Zola’s subsequent assessment of Fromentin’s own submissions which had once again been admitted to the annual Salon ( and ). While claiming that only the premature end to his sequence of Salon reviews (in the face of pressure from subscribers to L’Événement outraged by his unorthodox views) prevented him from exploiting his notes on Fromentin to the full, Zola falls back on the culinary ‘sauce épicée dont il assaisonne la peinture’;Footnote3 but an equally contrary aside is that ‘ce peintre nous a donné un Orient qui, par un rare prodige, a de la couleur sans avoir de la lumière’ (167). The least negative assessment is his comment that Fromentin’s Souvenir d’Algérie, securing the highest price of all those at an 1873 auction designed to raise funds for the forcibly displaced French citizens of Alsace-Lorraine: ‘très lumineux et très coloré, une des excellentes toiles de la vente’ (595).Footnote4 But this was undercut by Zola’s prefatory remark that he would restrain from any criticism of the 280 works generously offered by so many artists, his ‘prose aimable’ being consistent with the occasion: ‘On ne discute pas une aumône. […]. Je crois faire, moi aussi, une œuvre de charité, en me montrant doux pour tout le monde’ (593).Footnote5

Figure 3. Eugène Fromentin, Tribu nomade en marche vers les pâturages du Tell (1866, Atlanta, GA: High Museum of Art).

That there is something quite distinct about Zola’s long-held lack of sympathy for Fromentin is brought into sharper relief by juxtaposing his remarks on other painters on the 1866 jury. Daubigny, for example, was also an established artist benefitting from official approval as well as the huge popular success making him, like Fromentin indeed, one of the most affluent painters of the period.Footnote6 He was excepted from Zola’s diatribe by virtue of a stated awareness that his best paintings were commercial failures so that ‘M. Daubigny a contenté la foule sans trop mentir à lui-même’ (Citation2021, 168). But, over and above this artistic integrity, reinforced on a personal level (as Zola pointed out) by withdrawing from deliberations when the submissions of his son were being considered, Zola was familiar with Daubigny’s strategic solidarity with the young painters he was himself championing, evoking in some detail his repeated efforts, ultimately in vain (at least in 1866),Footnote7 ‘au nom de la vérité et de la justice’, to overcome the jury’s otherwise unanimous resistance to pictorial innovation. Théodore Rousseau, on the other hand, exemplified such narrow-mindedness (‘un des plus acharnés contre les réalistes’), as did François Français (1814–97) (‘il a été très dur pour les tempéraments vigoureux’). What is striking, however, is that, unlike Fromentin, both these recalcitrant members of the 1866 jury would in due course be positioned within a lineage marking the ‘revolutionary’ advent of a modern landscape painting confirming a new generic hierarchy: ‘Français, Corot, Daubigny’, Zola wrote in 1878, ‘abandonnèrent la formule classique, pour peindre sur nature’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 9: 617–618). Français, he had admitted in his attack on the jury of 1866, had (so he had been told) ‘débuté par des paysages assez largement compris et peints avec une certaine force’ (Zola Citation2021, 140). Rousseau’s rehabilitation was doubtless eased by his death the following year, but rested essentially on his sobriquet as ‘le grand refusé’, his consistent rejection by the Salon jury (‘refusé pendant dix ans, il rend dureté pour dureté’ (145)) testimony, as always in Zola’s assessments of the painters of his time, of an originality at odds with artistic convention. The year 1878, which saw the mounting of the first Universal Exhibition since 1867, provided Zola with the opportunity to engage in a retrospective account of the landscape genre’s development during that interval, fortuitously book-ended by the deaths of Rousseau and Daubigny: in the shadow of Courbet’s preeminence ‘venait toute une grande école de paysagistes: Théodore Rousseau, Daubigny, Corot, sans parler de Diaz et de Millet. De 1867 à 1878, ces artistes marchèrent toujours à l’avant et constituèrent la force et la beauté de notre école’ (Zola Citation2021, 542).Footnote8 At first sight, Fromentin’s exclusion from this pantheon of landscape artists is surprising. Only a year before Zola’s 1866 attack on the jury, he had engaged in a forensic reading of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s Du principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale in which could be found adumbrated an oft-rehearsed genealogy: Théodore Rousseau, Corot Daubigny, Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) and Fromentin as evidence that ‘l’école française va dans la même direction que Courbet’ (Proudhon Citation1865, 284). If it is not a little ironic, given Zola’s devastating critique of Proudhon’s version of art history (reprinted in his collected essays, also in 1866, under the accusatory title of Mes haines [Zola Citation1966–70, 10: 35–46]), that he would adopt most of this sequence of Courbet’s forebears, it is also significant that it should only be Fromentin’s name which would be eliminated in his own transcription of it.

As interesting is the fact that, in this respect, Zola did not subscribe to the views published by his close friend Théodore Duret in Les Peintres français en 1867. Quite apart from their shared support for Manet, the interchanges between the two men reveal an often reciprocal widening of critical horizons, such as Zola’s alerting Duret to the brilliance of Pissarro, left unmentioned in his book.Footnote9 In this, under the same heading of ‘Les naturalistes’ as Zola would use for one section of his review of the Salon of 1868,Footnote10 Duret places Fromentin in such a category alongside Corot, Daubigny, Millet, Constant Troyon (1810–1865) and Théodore Rousseau, describing him as a leading paysagiste in a ‘liste des peintres naturalistes que tout le monde s’est accordé à mettre au rang des maîtres’ (Duret Citation1867, 55). From this list, Fromentin is bracketed out by Zola as surely as he had failed to announce, in his note on the sale of the painter’s effects at the beginning of February 1877, the retrospective about to open at the École des Beaux-Arts (10 March–15 April ) at which almost 150 of his works were on show.

It could be argued that Zola’s dismissal of Fromentin was at least partly a matter of taste not attuned to his Orientalist pictures. This seems to not quite square with his repeated invocation of Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–60), recognised alongside Delacroix and Prosper Marilhat (1811–47) as one of the three great Orientalist painters of the century. Each in their own way took advantage of the opportunities afforded by French colonial expansion in North Africa, from the 1830 conquest of Algeria onwards, though their favourite sites extended to Greece, Turkey and the Middle East. Marilhat is never within Zola’s purview. But as early as 1867, in a letter trying to persuade his publisher to contract Manet to illustrate a collection of his short stories, Zola compared the painter’s hostile reception to that of ‘les premières œuvres de Decamps et Delacroix’ (Zola Citation1978–95, 1: 496). In his study of Manet the same year, a parenthetical anecdote reinforced the point: ‘Un écrivain me contait dernièrement qu’autrefois, ayant eu le malheur de dire dans un salon que le talent de Decamps ne lui déplaisait pas, on l’avait mis impitoyablement à la porte’ (Zola Citation2021, 493). On closer inspection, however, it is clear that Decamps was valued by Zola not for his Orientalist paintings as such but as yet another example of a notable artist initially rejected by the Salon: ‘Si l’abolition du jury est souhaitable’, he wrote in 1876, ‘ce serait uniquement pour l’empêcher de laisser à la porte pendant une dizaine d’années des gens comme Delacroix, Decamps, Courbet, Théodore Rousseau’ (308). That such rhetoric did not correspond to the facts hardly undermined the argument: although some of Decamps’s first paintings of the Orient, before he had ever seen it, were greeted with a degree of consternation, he had clearly not waited a decade before making his debut, barely aged 24, at the Salon of 1827; at that of 1834 he received a First Class Medal; he was invested with the Légion d’Honneur in 1839 and promoted to Officier in 1851. At the Universal Exhibition of 1855, he had some fifty works on display. So much for the notion that his talents were only belatedly celebrated by posterity! Nor were such honours his only achievement. As James Thompson has put it: ‘Decamps did not merely satisfy but actually helped create a public and critical enthusiasm for things Eastern’ (Citation1988, 59). It remains far from clear that this was an enthusiasm shared by Zola.

Delacroix (‘le premier coloriste de notre époque’), as major an influence on Fromentin as Decamps (‘un maître immortel’) (both cited by Wright Citation2000, 126–127), poses a somewhat different problem, given the extent to which he represents a Romantic aesthetic viewed by Zola as outdated. There are nearly eighty references to him in Zola’s art criticism, though the only Orientalist pictures he mentions by name are Scènes des massacres de Scio (1824) and La Mort de Sardanapale (1827) (both in the Louvre). It is a curious fact, however, that he actually owned a small Delacroix, described in the 1903 sale catalogue of the writer’s effects as an aquarelle of Types de zouaves, presumably one of the innumerable etchings and preparatory sketches related to the painter’s travels in North Africa after 1832,Footnote11 even if this testifies more to Zola’s admiration for its creator than its subject-matter. A number of Zola’s references add up to a continuing lament that the prices of work by painters like Fromentin dwarfed the derisory sums secured by Delacroix during his lifetime. But in the posthumous celebration of his genius, compared to that of the Old Masters, Zola singles out evidence of an originality consistent with his 1866 valuation of ‘un coin de la nature vu à travers un tempérament’: ‘Delacroix symbolisa la débauche des passions, la névrose romantique de 1830’ (Citation2021, 542), the result of which are the ‘œuvres éblouissantes’ (354) of a supreme colourist. Against this measure, Fromentin is found wanting, Zola declaring that his 1866 paintings were so devoid of that individuation that it would be pointless

de lui demander des arbres et des cieux plus vivants, et surtout de réclamer de lui une saine et forte originalité, au lieu de ce faux tempérament de coloriste qui rappelle Delacroix comme les devants de cheminée rappellent les toiles de Véronèse. (167)

This priority, however, was not just personal. For Fromentin is caught in the crossfire of a wider critical debate. In his writing on the visual arts, Zola is self-consciously militant: he describes himself as ‘un réfractaire en art’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 10: 722), a ‘chroniqueur casseur de vitres’; he lambasts contemporary art critics, making a name for himself by achieving a desired notoriety at their expense. One of his regrets about the premature end of his reviewing the Salon of 1866 was that he had intended to ‘aiguiser mes armes pour les rendre plus tranchantes’ (Citation2021, 167) by confronting other art critics. His denial of Fromentin’s colour values and luminosity (‘la couleur sans avoir de la lumière’), for example, provoked a satisfyingly public response from the influential Albert Wolff, who owned one of Fromentin’s works, reasserting in L’Evénement of 3 May 1866 that the painter was ‘un des plus grands coloristes du temps’. In the case of Baudelaire, whose art criticism Zola thought over-indulgent,Footnote12 he had to be more careful, bearing Manet in mind and in the knowledge that ‘une vive sympathie a rapproché le poète et le peintre’ (Citation2021, 479). He is implicitly at odds with Baudelaire’s clinging to the notion of landscape as a ‘genre inférieur’ (Citation1975–Citation76, 2: 660). But whether or not Zola was familiar with the pages devoted to Fromentin in Baudelaire’s Salon de 1859 (Citation1975–Citation76, 2: 649–651), the encomium was both sufficiently nuanced (‘il n’est précisément ni un paysagiste ni un peintre de genre’) and in many ways so consistent with Gautier’s more prolonged raptures (over the years since seeing Fromentin’s first two Orientalist paintings at the Salon of 1847) that he could be bypassed. For Gautier had found in the practitioners of the genre, and in Fromentin in particular, the intuition of a ‘universal poetic truth’ (Snell Citation1982, 63), reinforced by his own immersion in what he considered the cradle of humankind endlessly evoked in travel writing which Zola pointedly declined to defend: ‘il ne voyait pas le spectacle énorme de Paris; il avait besoin d’un chameau et de quatre Bédouins sales pour se chatouiller la cervelle’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 12: 369). Lamartine, he quipped, ‘n’a pas écrit un vers sur la banlieue parisienne’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 9: 616). For this turning away from France applied, Zola stressed, to ‘tout le groupe romantique’ whose representatives suffered from a collective ennui motivating a search for pastures new, whether afar or in the past: ‘l’école romantique nous promenait en Orient et nous enfermait dans les villes du Moyen Âge’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 12: 367). He was no less scathing in respect of Gautier’s reputed ‘infaillibilité extraordinaire’ as a critic, disparaging ‘les éloges que Gautier a distribué d’une main large à tous les artistes médiocres dont il a parlé’ (362): ‘il parla peinture comme il parlait théâtre, avec une indifférence parfaite et une complaisance exemplaire’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 10: 230), referring to him using ‘tous les adjectifs éblouissants du dictionnaire’ (722). While Zola shared his admiration for Delacroix, even owning a copy of his Journal, it was Gautier’s comparison of the latter with Fromentin which he found unacceptable; as indiscriminate as elevating Gérôme and his Orientalist pupil Mariano Fortuny (1838–74) to the same artistic pinnacle: ‘C’était en vérité une stupéfiante fantaisie, d’aller comparer Fortuny à Delacroix’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 12: 363). Gautier, by contrast, refused to acknowledge the pictorial talents of Courbet or Manet. He too had been a member of the 1866 jury Zola had taken to task, with mock sympathy for ‘toute l’angoisse d’un vieux romantique impénitent qui voit ses dieux s’en aller’ (Citation2021, 138). And there is a sense in which, through Fromentin, it is in fact Gautier, the most prestigious art critic of the day, who is the real target of Zola’s negative remarks.

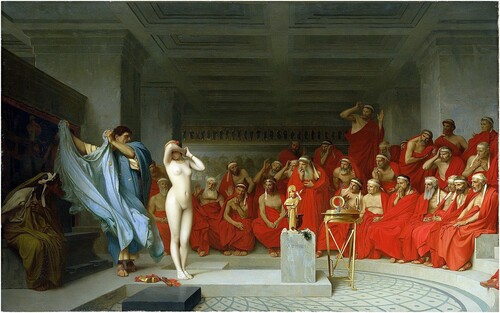

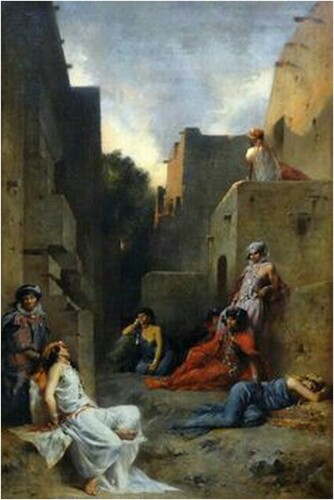

‘Mon ami Gautier’, Jules Castagnary implored from the opposing side of this debate, in his Salon of 1868, ‘pourquoi avoir délaissé le naturalisme, l’année même où le naturalisme rassemble ses forces et semble à la veille de l’emporter?’ (Citation1892, 1: 313). Against this rising tide of a newly-dominant aesthetic, Castagnary’s shifting attitude towards Fromentin can be tracked: in 1863, the painter was ‘aujourd’hui, de l’avis unanime, le premier parmi ceux de nos peintres qui ont choisi l’Orient pour domaine’ (Castagnary Citation1892, 1: 153); by 1869, Fromentin was seen to be anticipating the demise of the genre; the ‘quasi-insuccès’ of his Venice pictures of 1872 confirmed it: ‘c’est plus qu’une abdication, c’est la constatation d’un décès’ (Castagnary Citation1892, 2: 31); two years later, a return to a further Souvenir d’Algérie (Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland) and Un ravin (Kansas City, Missouri: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) () ‘qui ont l’éclat et la vivacité des beaux temps de l’auteur (117), offered hope of a possible resurrection; but Fromentin’s last paintings, at the Salon of 1876, the two which had provoked Zola’s own contempt (see above), were terminal: ‘Dans la prétendue Haute-Egypte qu’il étale à nos regards, un Nil chocolat coule entre des rivages chocolat, tandis que des femmes au teint chocolat plongent des vases chocolat dans ces flots chocolat’ (234). We may need to revise Wright’s view that Orientalism was ‘not central’ (Citation2000, 432) to the debate. For what Castagnary had called in 1866 ‘le cosmopolitisme géographique de l’école romantique’, with Orientalism as the first such manifestation of it to be discarded,Footnote13 was fundamentally incompatible with the realist movement headed, in his view, by Courbet but extended to ‘toute la jeunesse idéaliste et réaliste (le Naturalisme comporte les deux termes), qui vient après lui: Millet, Bonvin, Ribot, Vollon, Roybet, Duran, Legros, Fantin, Monet, Manet, Brigot’ (Castagnary Citation1892, 1: 240). There is little doubt that Zola was familiar with Castagnary’s writing, ‘sans que’, as François-Marie Mourad has put it, ‘l’auteur de Mon Salon ait pris la peine de signaler sa dette’ (Citation2003, 349). There is little doubt either that he subscribed to Castagnary’s rejection of Orientalism on the grounds that there remained ‘pour domaine unique des paysagistes français, la France, terre incomparable’ (Citation1892, 2: 31). Towards Gérôme, Castagary is more ambivalent: he condemns his 1857 paintings of Egypt as lacking verisimilitude; praises his Promenade du harem (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum of Art), depicting an excursion of its inmates on a boat, at the Salon of 1869, ‘quoique dans une tonalité sans doute un peu grise pour l’Orient’ (1: 358); and marvels ironically at the cleanliness of the slippers left at the door by worshippers who had supposedly crossed the desert to appear in his Santon, à la porte d’une mosquée (1876). Fromentin too, in his own review, mocked ‘la vérité avec laquelle cette cordonnerie est imitée’ (Wright Citation2017, 102). Zola was even less forgiving of this ‘peinture sur porcelaine’ (Citation2021, 298): ‘un pareil art n’est autre qu’une amusette’ (325). Deriding the perfect finish of Gérôme’s tasteful Neoclassical renderings of episodes from ancient history, Zola accuses him of pandering, like Fromentin, to ‘tous les goûts’ (535) and earning a fortune as a result. Of his minutely detailed Orientalist paintings, he mentions the ‘petite note sentimentale’ (553) of his L’Arabe et son coursier (1872), But he also compares to the modern nude the stereotypical artifice of the Odalisque theme popularised by Ingres and rehearsed in Gérôme’s 1861 Phryné devant l’Aréopage (Hamburg: Kunsthalle) (), described as ‘une petite figure nue en caramel que des vieillards dévorent des yeux’ (553) as surely as would the prurient spectator at the Universal Exhibition of 1867. Zola describes Gérôme’s painting as being as titillating as seraglio pictures such as Les Femmes au bain (1876) (Vesoul: Musée Georges-Garret) at the Universal Exhibition of 1878, while engravings of other ‘sujets piquants’ like La Danse de l’Almeh (1863) (Dayton, Ohio: Institute of Art) took pride of place in ‘les ménages de garçons’ (Citation2021, 535). For those not seduced by Orientalism, the travesties were the stuff of scenes from the Arabian Nights: contented slaves, docile concubines with perfect skin, and mosaic-encrusted Moorish baths as beautiful as the glittering desert sands. Apart from a breast occasionally revealed for male delectation, Fromentin’s more juste milieu Orientalist series (Thompson Citation1988, 78) are largely free of such invidious fantasies: his point of view is external (buildings, encampments, caravans, figures in the open in repose or prayer, vistas, etc.) rather than intimately intrusive; the painter is ‘uncomfortable’ (Thompson and Wright Citation1987, 224) in trying to represent the potentially erotic,Footnote14 as in his 1867 Femmes des Ouled-Nayls: dans un village du Sahara (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago) (); he is manifestly more at ease in depicting picturesquely-robed tribesmen on rearing stallions (see ). Zola’s reference to Fromentin’s ‘Orient faux’ is almost a default critical nostrum, echoed in due course by Huysmans deploring the exotic genre’s airbrushing out of dirt, indigenous poverty and disease in ‘un Orient de convention, un Orient romantique, une Asie de décor’ (Citation2006, 259).

Figure 4. Eugène Fromentin, Un ravin. Souvenir d’Algérie (1874, Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 34–103). Photo: Jamison Miller.

Figure 6. Eugène Fromentin, Femmes des Ouled-Nayls. Dans un village du Sahara (1867, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago).

It is in this same critical frame that Zola’s assessment of Fromentin as a novelist has to be seen: Dominique (1863) is ‘médiocre’ because it is ‘calqué sur les ouvrages de George Sand’ (Zola Citation2021, 330). Not only was it dedicated to the latter, as testimony to affinities sealed into a friendship dating from Fromentin’s triumph at the Salon of 1859, but Sand had also contributed to its composition: on her advice, Fromentin had made a number of changes to his text, including inserting in chapter 17 of Dominique an analogy making explicit a debt to her Mauprat (1836), a novel that Zola himself found tiresome with its ‘poupées idéales du roman d’autrefois’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 12: 407). Such a perspective is elaborated at length in the study he devoted to Sand (389–413) in the July issue of Le Messager de l’Europe immediately following the one, cited at the beginning of my essay, in which he had discounted Fromentin’s reputed talents as both painter and writer. Prompted by Sand’s death, only a month earlier, on 8 June 1876, Zola’s homage to ‘cette haute figure littéraire’ barely masks the definitive liquidation of his juvenile enchantment with her work. In the final analysis, he writes, ‘George Sand continue La Nouvelle Héloïse et achève René’, and suggests that she is the direct subjectivist heir of Rousseau, Chateaubriand and Bernardin de Saint-Pierre: ‘Elle déformait toutes les réalités qu’elle touchait’. By implication, Fromentin’s Dominique simply perpetuated the anachronistic vein of the confessional roman personnel. For all her creative flair, ‘George Sand représente une formule morte, voilà tout’. In her case as in that of Gautier, it can be argued, Fromentin simply afforded Zola the opportunity to reinforce his increasingly urgent argument that the Romantic aesthetic had had its day (Zola Citation1966–70, 12: 393).

It remains true, however, that Zola’s 1876 commentary on Fromentin is worth another look. Its pretext was consideration of Edmond Duranty’s La Nouvelle Peinture, timed to coincide with the opening of the second Impressionist exhibition, as its extended title underlines.Footnote15 Duranty’s brochure was itself partly responding to Fromentin’s Les Maîtres d’autrefois, at that very moment being serialised, as Zola too noted (‘des articles fort curieux’ [Citation2021, 336–338]), in the Revue des Deux Mondes. Fromentin’s erudition, grounded in reflections provoked by systematic visits to museums in Belgium and Holland in the summer of 1875, ranged far and wide. But it was in the fourth of the six instalments, published on February 15, that a chapter subsequently entitled, in volume form (22 May 1876), ‘Les influences de la Hollande sur le paysage français’ had caught Duranty’s eye in putting together his privately-printed April text. Fromentin himself had conceived it as a reminder to contemporary artists of the teachings of the Old Masters, although his characteristically ‘genteel discretion’ (Wright Citation2000, 530) meant that the apparently forgetful were not individually named.Footnote16 As Zola noted, his ‘articles d’art’ were ‘curieux à lire en ce qu’ils montrent comment l’ancienne génération d’artistes juge la nouvelle’ (Citation2021, 330). Minimal, but indicative, variants between the Revue des Deux Mondes text in question and Duranty’s partial transcription of it make it clear that Zola directly cites ‘un critique solide’ while sustaining the illusion that he has the periodical in hand. A ‘principled attack’ (Wright Citation2000, 535) both their commentaries may have been. But whereas Duranty ([Citation1876] Citation1989, 108–10) faithfully cites Fromentin’s observations, Zola, as I have shown elsewhere (Lethbridge Citation2020, 121), traduces them. He underlines the extent to which Fromentin ‘se cramponne obstinément’ to tradition, and is further damned by association with Gustave Moreau,Footnote17 but it is to misrepresent Les Maîtres d’autrefois to assert that its author ‘annonce la victoire prochaine de la peinture réaliste’. Zola’s readers would hardly have been able to discern that all the quotations he exploits in support of his modernist values are so decontextualised as to strip them of what in fact Fromentin deplored: ‘Il semble que la reproduction mécanique de ce qui est’ and the ambition to ‘lutter d’exactitude, de précision, de force imitative’, prioritised over imaginative elaboration, uniquely testified to pictorial talent (Fromentin Citation1984, 717).

No less ‘curious’, however, is that this is also the point at which opposing frames begin to overlap. For Duranty’s La Nouvelle Peinture marked a decisive moment, paradoxically, in Zola’s increasing disenchantment with ‘la nouvelle peinture’ itself. The perspectives shared by him and Fromentin stretch both back and forwards: their joint debt to Taine’s principles of art history; the emphasis of the prologue to Les Maîtres d’autrefois on identifying in Flemish painters ‘quelques côtés physionomiques de leur génie et de leur talent’ (Fromentin Citation1984, 567), comparable to Zola’s focus on ‘une individualité’ (‘ce que je cherche dans un tableau, c’est un homme’ (Citation2021, 146)); the fact that both men single out Corot and Rousseau as instrumental in the development of modern landscape; and the fact that Zola critiques Caillebotte’s quasi-photographic pictures at the Salon of 1876 in the very same article as he passes over Fromentin’s condemnation of ‘l’étude photographique’: ‘La photographie de la réalité’, Zola writes, ‘lorsqu’elle n’est pas rehaussée par l’empreinte originale du talent artistique, est une chose pitoyable’ (341). But it is in the coincidence of reading La Nouvelle Peinture and his distancing himself from Impressionism that he seems, with the wisdom of hindsight, to have fortuitously validated Fromentin’s intention (as he put in a letter of December 1875) to ‘inspirer à quelques-uns des doutes sur eux-mêmes’ (Wright Citation1995, 2: 2060). Fromentin had invoked Rembrandt to prove that there was nothing innovatory about pleinairisme (Zielonka Citation2008). Zola contrarily finds endorsement in Fromentin’s ‘Le plein air, la lumière diffuse, le vrai soleil, prennent aujourd’hui dans la peinture une importance qu’on ne leur avait jamais reconnue’; but what had actually followed these ironically italicised allusions was ‘et que, disons-le franchement, ils ne méritent point d’avoir’, and he had prefaced the part of the sentence cited by Zola with similar reservations: ‘on ne saurait dire à quel point le grand jour des champs, entrant dans les ateliers les plus austères, y a produit des conversions et des confusions’ (Fromentin Citation1984, 717). But Zola’s own sense of that indirection, catalysed, ironically enough, by Duranty’s oblique allusion to the theory of complementary colours retailed since 1839 by Michel-Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) and generally accepted by even the most conservative of art critics, is unmistakable. By 1880, the laudable efforts of the Impressionists are seen to be compromised by the excesses of ‘les effets de coloration les plus imprévus’ (Zola Citation2021, 376). In the work-notes for L’Œuvre, prepared in 1885–86, Zola’s ascribing to his fictional painter ‘quelques théories des impressionnistes, le plein air, la lumière décomposée, toute cette peinture nouvelle’ is inseparable from the latter’s ultimate failure.Footnote18 In his final published engagement with the visual arts, in 1896, he refers to ‘le fameux Plein air’, so ubiquitous ‘qu’aujourd’hui il n’y a plus que du plein air’ (Zola Citation2021, 403).

More significantly, the correlative of this mise-en-question of ‘la nouvelle peinture’ is a reevaluation, consistent with Fromentin’s, of the Old Masters. While clearly espousing traditional academic criteria and being deeply irritated by suggestions that this precluded appreciation of modern landscapes,Footnote19 Fromentin insisted that only by recognising and remodelling an artistic heritage (in this case Dutch) could contemporary painting lay claim to originality. The only respect in which Meyer Schapiro qualified his admiration for Les Maîtres d’autrefois was with regard to its ‘indiscriminate’ (Citation1994, 131) refusal to acknowledge any such modern achievement. But there is in fact one landscape artist who fulfils Fromentin’s criteria. And although this artist is unnamed, it is tempting to speculate on the identity of the painter whose work, devoid of human figures, he sees characterised by ‘la couleur profonde et sourde, la matière épaisse et riche’, with ‘une grande finesse d’œil et de main’ in spite of ‘les négligences voulues et les brutalités un peu choquantes du métier’. The painter in question, Fromentin goes on, ‘joint à l’amour vrai de la campagne l’amour non moins évident de la peinture ancienne et des meilleurs maîtres’, thereby providing the ‘trait d’union qui nous rattache aux écoles des Pays-Bas’, ‘le seul coin de la peinture française actuelle où l’on soupçonne encore leur influence’ (Fromentin Citation1984, 719). In a note to this passage (1596), Guy Sagnes’s editorial scepticism in relation to Jacques Foucart’s hypothesis that Fromentin has François Bonvin (1817–87) in mind is certainly justified, not least because Bonvin was mainly known for his natures mortes and scènes de genre. My earlier erroneous suggestion (Citation2020, 122, misled by Duranty [Citation1989, 118]) was that it might have been Johan-Bartold Jongkind (1819–91) on account of his own apprenticeship in the museums of his native Holland from which Fromentin himself had just returned. But never in his life did Jongkind paint any landscape of the kind Fromentin evokes here. Altogether more likely, given the specific pictorial qualities highlighted and the similar massive geological formations in the background of so many of Fromentin’s paintings (see , and ), is Courbet (), the discretion in not naming him being also the better part of valour in the context of the painter’s controversial reputation. For apart from being ‘resolute in his defence of Courbet’ (Wright Citation2000, 437) at the Salon of 1872, the thrust of Fromentin’s undated recommendation that he be awarded the Légion d’Honneur is revealing: with his ‘grands dons’, exerting ‘sur notre jeune école une influence considérable’, ‘salué de tous les côtés et rallié quand même à l’aristocratie du talent dont il fait partie malgré lui’ (Fromentin Citation1984, 1118), it was only his outrageous public pronouncements which had prevented him being honoured by the State over the previous decade. Zola would consistently rehearse this same view. And he too was aware of Courbet’s 1847 visit to Amsterdam and the Hague, where Rembrandt had made such a lasting impression on him. For polemical reasons, he had initially written of the painter’s liberation from Dutch influence: ‘Courbet a commencé par imiter les Flamands […] mais sa nature se révoltait, et il se sentait entraîné par toute sa chair […] vers le monde matériel qui l’entourait’ (Citation2021, 163). There are other artists celebrated by both Zola (in his novels as well as in his art criticism) and Fromentin: Van Eyck, Memling and, of course, Rubens and Rembrandt. But in Zola’s ultimate differentiation of the timeless solidity of the Old Masters from the increasing sketchiness of the Impressionists, it is Courbet, rather than Manet, who exemplifies the pictorial imperatives central to Les Maîtres d’autrefois: ‘Courbet était un maître ouvrier’, Zola would write in 1880, ‘qui a laissé des œuvres impérissables, où la nature revit avec une puissance extraordinaire […], un magnifique classique qui reste dans la plus large tradition des Titien, des Véronèse et des Rembrandt’ (Citation2021, 373). In other words, Courbet was, for Zola, an ‘Old Master’ for modern times.

Figure 7. Eugène Fromentin, Arabes traversant une rivière au gué (1873, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catherine Lorrillard Wolfe Collection).

Figure 8. Gustave Courbet, Le Rocher de Hautepierre (c. 1869, Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago. Emily Crane Chadbourne Fund).

By way of conclusion, it has to be admitted that it is only in retrospect that such a reframing of Zola and Fromentin’s positioning can be effected. What is equally clear is that if Zola’s writing on Fromentin is essentially polemical in intent, it carries the risk of being devalued as art criticism by its ‘manque de nuances’ (Thompson and Wright Citation1987, 320), blind to the intellectual sophistication with which, as recent scholarship has demonstrated (Graebner Citation2018), Fromentin explored the complexities of landscape as a genre. But no less oversimplified, it can be argued, is Fromentin’s dismissal of Manet’s ‘jeunes camarades’ as ‘néo-coloristes’ (Citation1984, 729–31): ‘Ils ont des yeux et une main qui ne savent ni bien voir ni bien manier leur outil’ (1182). Both sets of prejudiced agendas provide yet more evidence of the irreconcilable oppositions and cultural instabilities of the period.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Lethbridge

Robert Lethbridge is a Life Fellow of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, Emeritus Professor of French Language and Literature in the University of London, and currently Hon. Professor at the University of St Andrews. He has published extensively on both Zola and on the relationship between literature and the visual arts in nineteenth-century France. This includes a critical edition of Zola’s Écrits sur l’art (Classiques Garnier, 2021). His Zola’s Painters (Legenda Research Monographs in French Studies) was published in 2022.

Notes

1 At the auction of Laurent Richard in April 1873, Zola noted the 40,500 francs paid for Fromentin’s La Fantasia (1869) (Citation2021, 651); 13,300 francs for a painting (referred to by him as La Chasse au faucon, but in fact Les Bords du Nil) at another sale two years later (656); and 15,000 francs for Le Ravin () (661).

2 No less indicative of Zola’s view of Fromentin’s adherence to convention is that it was possible to award the 1868 Prix de Rome for history painting to La Mort d’Astyanax by Édouard Blanchard (1844–79), with its attempted ‘vague parfum moderne’ by virtue of the executioner being ‘un Arabe qu’il a pris dans un tableau de Fromentin’ (Citation2021, 623).

3 In the original article, in L’Événement of 20 May 1866, this phrase read ‘dont il assaisonne la nature’; the substitution of ‘peinture’, effected (deliberately or not) during the reprinting of the text in Mon Salon, leaves open the question of which of these plausible alternatives Zola intended. On the prevalence of the metaphor in contemporary art criticism more generally, including the sense of ‘cooking the books’, see Leduc-Adine (Citation1980).

4 The painting was purchased, perhaps for a third party, by Hector Brame (1831–99), the dealer who would be one of the models for the character of Naudet in Zola’s L’Œuvre (1886); although the price of 6000 francs attracted considerable press attention, it remains difficult to identify the specific canvas (in Le Gaulois of 16 April 1877, it is referred to as Un paysage algérien). The sale does not figure in the provenance of any painting in the catalogue raisonné (Thompson and Wright Citation1987).

5 Two other Orientalist paintings benefitted from this (relative and exceptional) critical goodwill: Une vue à Constantinople by Germain Brest (1823–1900) (‘le pays du soleil, un Orient raisonnablement vrai’); and La Porte de la Mosquée (Algérie) by Victor Huguet (1835–1902) (‘un pendant au tableau de Brest cité plus haut, d’une lumière plus éclatante encore’) (Zola Citation2021, 594–595).

6 Daubigny’s first successful submission to the Salon had been as long ago as 1838. Both those in the Salon of 1852 were purchased by the French government. The following year, Napoléon III bought Daubigny’s Étang de Gylieu (awarded a First Class Medal at the Salon of 1853) for his personal collection at St Cloud. Leading politicians also patronised his work. His Printemps (Salon of 1857) went directly to the Musée du Luxembourg, shortly followed by the award of the Légion d’Honneur. Between 1871 and 1873, he earned 369,800 francs, at least as much as, or even more than, Fromentin.

7 By securing, in the election for membership of the jury of the 1868 Salon, the vast majority of votes from eligible artists (no longer restricted to previous winners of medals and the Prix de Rome), Daubigny was able to exert an influence (resulting in the admission of works by Bazille, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Sisley and Morisot) for which he was never forgiven by the authorities. When Monet and Sisley were rejected once again in 1869 and 1870, Daubigny resigned from the jury on principle, as did Corot, both artists admired by Zola thereby further differentiated from Fromentin.

8 This repeats almost exactly the lineage predicated in Zola’s review of the Salon of 1875, except for the belated inclusion of Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, one of the Barbizon painters in the late 1830s, whose death at the age of 69 on 18 November 1876 had prompted Zola to pen an admiring obituary notice: ‘un des derniers survivants de la grande phalange, qui a fondé notre école de paysage’ (Citation2021, 642).

9 With no other contemporary art critic did Zola have a closer personal and professional relationship, as detailed by Joy Newton (Citation1988). Duret was as opposed to Napoléon III’s regime as Zola (recruiting him to write for the politically radical La Tribune which he had founded in 1867), but this seems not to have mitigated his admiration for Fromentin’s work.

10 Although Taine had already used it in an article in Le Journal des débats of 23 February 1858, the currency of the term dates from Jules Castagnary’s (1830–88) designation of the ‘École naturaliste’ in his writing about the Salon of 1863 (Citation1892, 1: 139–154). By the time of this leading art critic’s review of the Salon of 1869, the ‘grande armée des paysagistes’ (142) had become ‘une grande armée victorieuse’, explaining that ‘le naturalisme […] entrait par la porte du paysage’ (331). The term relates to the natural (or external) world rather than suggesting the analogy with the natural sciences subsequently informing Zola’s Naturalism. Fromentin only uses it in opposition to the broadly realist trend ‘dans notre école au moment où l’amour du naturel […] sert de programme à certaines doctrines en vertu desquelles l’exactitude la plus terre à terre est prise à tort pour la vérité’ (Citation1984, 724).

11 It was bought by the collector Léon Osrodi (1855–1923) for a mere 60 francs, which can be compared with the 720 francs he paid for Cézanne’s Vue de Bonnières (1866) (according to the procès-verbal, in Archives de Paris: Paul Chevallier files D.5E3/54 and D48E3/70–79).

12 In a brief mention of Baudelaire’s Curiosités esthétiques, in Le Gaulois of 10 January 1869, Zola wrote that his essentially literary approach meant that ‘ses critiques d’art ne resteront pas comme des jugements solides et justes’, adding that Baudelaire, ‘sans avoir la bienveillance de Théophile Gautier […], est aussi singulièrement doux pour les artistes qu’il ne pouvait aimer’ (Citation1966–Citation70, 10: 777).

13 ‘Il repousse’, Castagnary wrote of ‘le naturalisme’, ‘d’abord l’orientalisme, l’helvétianisme, l’italianisme, l’algérianisme, et le reste’ (Citation1892, 1: 292).

14 Exceptions include his Femmes arabes en voyage (1873, Houston: Menil Foundation), in which there is a focus ‘moins sur le dur labeur des femmes que sur la sensualité de leur peau’ (Thompson and Wright Citation1987, 220) and the sprawled Femme morte (1867, Private Collection), considered ‘the most exquisite portrayal of sexuality in Fromentin’s œuvre’ (Wright Citation2000, 402).

15 La Nouvelle Peinture – À propos du groupe d’artistes qui expose dans les galeries Durand-Ruel (Paris: E. Dentu, 1876).

16 This is not the case, however, in his unpublished notes: he does not forgive Manet for having adopted, ‘avec un œil moins juste, un sentiment de la nature bien inférieur’, ‘la dernière manière’ of the 80-year-old and ‘senile’ Frans Hals (Fromentin Citation1984, 1181), in the context of contemporary critics pointing out the debt to Hals of paintings like Manet’s Le Bon Bock (1873).

17 Duranty’s reference in 1876 to Fromentin’s personal and aesthetic affinities with Moreau, ‘nourri de poésie et symbologie ancienne’ (Citation1989, 110) is picked up by Zola in this same article of 1876: ‘la plus étonnante manifestation des extravagances où peut tomber un artiste dans la recherche de l’originalité et la haine du réalisme. […]. Gustave Moreau s’est lancé dans le symbolisme’ (Citation2021, 328).

18 BnF, Nouvelles Acquisitions françaises, Ms 10316, fols 300–301.

19 Huysmans anecdotally refers to Fromentin objecting that ‘vous m’embêtez avec votre modernité’ (Citation2006, 132) and arguing that portraiture was no less artificial than his rendering of Oriental scenes. Fromentin defends ‘une peinture cosmopolite’ (Citation1984, 716). More problematic is an interpretation of his Orientalist pictures as testifying to ‘une rupture avec la tradition exotique du début du siècle’ (Kapor Citation2005, 67).

References

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1975–76. Œuvres complètes. Edited by Claude Pichois, 2 vols. Paris: Gallimard, Pléiade.

- Castagnary, Jules. 1892. Salons. 2 vols. Paris: Charpentier.

- Duranty, Edmond. 1989. “La Nouvelle Peinture (1876).” In Les Écrivains devant l’impressionnisme, edited by Denys Riout, 108–134. Paris: Macula.

- Duret, Théodore. 1867. Les Peintres français en 1867. Paris: Dentu.

- Fromentin, Eugène. 1984. Œuvres complètes. Edited by Guy Sagnes. Paris: Gallimard, Pléiade.

- Fromentin, Eugène. 1995. Correspondance d’Eugène Fromentin. Edited by Barbara Wright. 2 vols. Paris: CNRS-Editions: Universitas.

- Gonse, Louis. 1881. Eugène Fromentin, peintre et écrivain. Paris: Quantin.

- Graebner, Seth. 2018. “The Landscape to the South: Fromentin and the Postcolonial Nineteenth Century.” French Studies 72 (2): 194–208. doi:10.1093/fs/knyOO4.

- Huysmans, J.-K. 2006. Écrits sur l’art. 1867–1905. Edited by Patrice Locmant. Paris: Bartillat.

- Kapor, Vladimir. 2005. “La Couleur anti-locale d’Eugène Fromentin.” Nineteenth Century French Studies 34 (1-2): 63–74. doi:10.1353/ncf.2005.0059.

- Leduc-Adine, Jean-Pierre. 1980. “Le Vocabulaire de la critique d’art en 1866, ou ‘les cuisines des beaux-arts’.” Les Cahiers naturalistes 54: 138–153.

- Lethbridge, Robert. 2020. “Translating and Traducing: Zola and the Art of (Mis)Quotation.” Australian Journal of French Studies 57 (1): 115–124. doi:10.3828/AJFS.2020.12.

- Mainardi, Patricia. 1987. Art and Politics of the Second Empire. The Universal Exhibitions of 1855 and 1867. London: Yale University Press.

- Mourad, François-Marie. 2003. Zola critique littéraire. Paris: Honoré Champion.

- Newton, Joy. 1988. “Zola and Théodore Duret: Portrait of an Art Critic” Nottingham French Studies 27 (1): 13–23; 27 (2): 13–24. doi:10.3366/nfs.1988.002.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. 1865. Du principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale. Paris: Garnier frères.

- Schapiro, Meyer. 1994. “Eugène Fromentin as Critic.” In Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society, 103–134. New York: George Braziller.

- Seillan, Jean-Marie. 2014. “Zola et le fait colonial: les raisons d’un rendez-vous manqué.” Les Cahiers naturalistes 88: 13–26.

- Snell, Robert. 1982. Théophile Gautier: A Romantic Critic of the Visual Arts. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Thompson, James. 1988. The East Imagined, Experienced, Remembered. Orientalist Nineteenth-Century Painting. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland.

- Thompson, James, and Barbara Wright. 1987. La Vie et l’œuvre d’Eugène Fromentin. Paris: ARC.

- Wright, Barbara. 2000. Eugène Fromentin: A Life in Art and Letters. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Wright, Barbara. 2017. “The Landscapes of Eugène Fromentin and Gustave Moreau.” In Translation and the Arts in Modern France, edited by Sonya Stephens, 98–112. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Yee, Jennifer. 2016. The Colonial Comedy. Imperialism in the French Realist Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zielonka, Anthony. 2008. “Eugène Fromentin and Rembrandt’s Painterly Language of Light.” Romance Quarterly 55 (3): 231–240. doi:10.3200/RQTR.55.3.231-240.

- Zola, Émile. 1966–70. Œuvres complètes. Edited by Henri Mitterand. 15 vols. Paris: Cercle du livre précieux.

- Zola, Émile. 1978–95. Correspondance. Edited by B. H. Bakker and others. 10 vols. Montreal: Presses universitaires de Montréal.

- Zola, Émile. 2021. Écrits sur l’art. Edited by Robert Lethbridge. Paris: Classiques Garnier.