ABSTRACT

Augustine Fouillée's (alias G. Bruno's) Le tour de la France par deux enfants, a children's geography textbook initially published in 1877, has long been considered a nation-building tool in the Third Republic. This essay draws on critical approaches to cartography in order to show how the contradictory modes of mapping throughout the Tour can clarify its generic complexity. Such forms of spatial knowledge would take on new resonances through the book's travels, adaptations, and remediations in a colonial context, from Indochina to French West Africa. Tracing these migrations offers a dialectical, transnational approach to the spatial analysis of literary narrative.

Introduction

Midway through Gustave Flaubert’s ‘Un cœur simple’ (1877), Félicité turns to an illustrated geography book in order to imagine her nephew Victor’s life in Havana. When Monsieur Bourais, overseeing her efforts, launches into an explanation of longitudes, she is bewildered. When he identifies Havana on the map ‘dans les découpures d’une tache ovale, un point noir, imperceptible’ (Citation1973, 40), the cross-hatched lines merely give her a headache. And when she asks Bourais to point out on the atlas the house where Victor lives, he chortles over her ‘ignorance’ (40). Flaubert himself, who assumed the role of geography tutor for his niece Caroline, had long been fascinated by atlases: ‘quelle chose énorme qu’un atlas’, he wrote in 1855, ‘comme ça fait rêver !’ (Citation1980, II: 587). Although ‘Un cœur simple’ takes place earlier in the century, Bourais is more recognizable within the story’s Third Republic context of publication, as the character extols the kind of standardized, institutional geographic knowledge through which republican values could be imparted to students (Furet and Ozouf Citation1977). In that sense Bourais is hardly a mouthpiece for Flaubert but rather a typical Flaubertian bourgeois, whose confidence as to the superiority and objectivity of a flat, two-dimensional map is no more than an idée reçue.

As a kind of cartographic allegory, the scene above underlines the uneasy collusion between the pedagogical and literary aspects of Third Republic geography, especially as it was being institutionalized as an academic discipline and field of professional research. If the atlas epitomizes an abstract, topographical representation of space, Félicité’s ‘ignorance’ can be read against the grain as a desire for a more embodied, haptic relation to place – one that might better allow her to ‘dream’, that is, to imaginatively inhabit another world.Footnote1 While knowing how to read a modern map is useful for answering certain questions, it might prove altogether unfit for responding to others.

Keeping these two competing cartographic paradigms in mind, this essay returns to another classic Third Republic text – at once cartographic narrative, travelling commodity, literary monument, and didactic treatise – in order to analyse its own complex and contradictory articulation of spatial knowledge across various scales. Le tour de la France par deux enfants was a geography textbook first released in 1877 by Augustine Fouillée, who published under the name G. Bruno. It sold three million copies in its first ten years – a number that would reach seven million by 1914. In fact, it was France’s bestselling book between 1877 and the Second World War.Footnote2 The text is structured around the journey of a pair of orphaned brothers, Julien and André, who leave Lorraine in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and travel throughout the country, discovering France’s regional gifts and eventually settling on a farm in the Loire Valley (which they first must restore, as it lies in ruins from the Prussian offensive).

The preface to the Tour’s first editions began with what, by the late 1870s, had become an almost Flaubertian idée reçue regarding French geographical inferiority: ‘On se plaint continuellement que nos enfants ne connaissent pas assez leur pays’ (Bruno Citation1985, 4). Virtually all commentators have aligned in considering the Tour as a nation-building tool under the aegis of Jules Ferry’s educational expansion and reforms. It was memorably dubbed ‘le petit livre rouge de la République’ in Jacques Ozouf and Mona Ozouf’s contribution to Pierre Nora’s Les Lieux de mémoire (Citation1997, 291). Uniting regional diversity with organicist metaphors of national harmony, the textbook sought to forge a new definition of France in the aftermath of the Prussian defeat (Dupuy Citation1953; Maingueneau Citation1979; Ozouf and Ozouf Citation1997; Thiesse Citation2021). The brothers’ cartographic trajectory would redeem the loss of the ‘provinces perdues’, as Alsace and Lorraine had come to be known, in a compensatory fantasy of national unity that could also salve anxieties of urban radicalism unleashed by the Paris Commune.

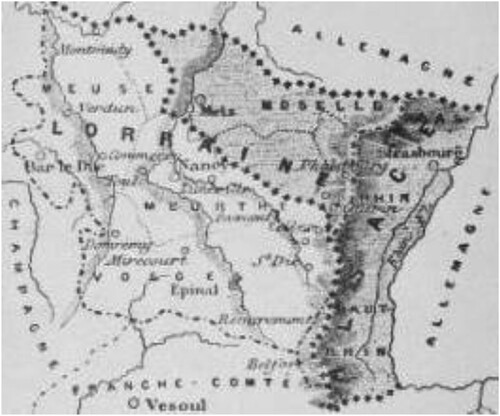

But where did the nation begin – and where did it end? Starting with the 1884 edition, the textbook often included two-dimensional maps of (hexagonal) France among its paratextual material. These maps usually featured Alsace and Lorraine in cross-hatched, shaded grey (see ). The color-coded exception thus exemplified a particular historical and political message – once French, these regions might once again become so. Certainly, textbooks like the Tour played no small part in helping to solidify the stable borders of the Hexagone and to establish a definition of French identity and citizenship that aligned with political and administrative, not to mention racial and social, boundaries.

Yet taking the production and reproduction of metropolitan France’s borders for granted risks rehearsing the Third Republic’s ideology of itself. It succumbs, further, to a long history of French metropolitan and colonial histories proceeding along isolated tracks.Footnote3 In their recent call for a postcolonial approach to nineteenth-century French studies, Charles Forsdick and Jennifer Yee argue for analysing ‘literary history – the evolution of genres and styles – as inextricably imbricated in political and social history, including imperialism in its various forms’ (Citation2018, 174). Bruno’s Tour enables further scrutiny of such imbrications, in part through the kinds of ‘contrapuntal and transhistorical reading practices’ (174) evidenced by that special issue. In the second half of this essay, I trace the Tour’s peregrinations, adaptations, and movements within and across state borders, especially as it was remediated in French colonial contexts. Its afterlives illuminate how hexagonal geography developed in dialectical construction with colonial expansion (Stoler and Cooper Citation1997), as well as how this process could take shape at various scales, not only metropole and colony but also across region, province, ocean, coastal waterway, pays, and colonial trade route.

In nineteenth-century French studies, some of the most fruitful engagements with literary geography have included phenomenological approaches, including Bachelardian poetics and Situationist psychogeography, as well as Marxist theories encompassing the global production of space and scale.Footnote4 Scholars have drawn on digital scholarship, postcolonial and anticolonial thought, and ecological criticism to explore how literature works to construct, not just reflect, a sense of place (Tally Citation2013, Citation2014; Moretti Citation1999; Conroy Citation2021).

Cultural geographers, for their part, have interrogated the rhetorical and discursive function of mapping at least since Brian Harley’s (Citation1989) influential essay ‘Deconstructing the Map’ (itself informed by poststructuralist and other French critical theory). It is now widely assumed that maps – like literary texts – are not mimetic representations of the world but rather discursive tools and mediatized objects with their own specific, contingent histories. Matthew Edney (Citation2019) has gone so far as to argue that any definition of the map as such idealizes and reifies heterogeneous forms of spatial knowledge. He proposes to explore ‘ways of mapping’ rather than ‘the map’, in order to better articulate the array of spatial imaginaries that scholars might wish to examine. For as Denis Cosgrove (Citation1999, 11) puts it, ‘The map’s pretence to stable, uniform and smoothly mobile knowledge depends upon inherently unstable, uneven, fragmentary, specifically positioned and haphazardly transferred information’ (11–12). This hermeneutic instability offers a bridge to literary scholars’ own understanding of the interpretive breadth of imaginative narrative. In the wake of the poststructuralist critique, we can move beyond simply exposing the map as an ideological construct and examine the variety of contexts in which mapping has taken place, by whom, and how those uses might be contested.

I thus begin by looking closely at the heterogeneous ‘genres and styles’ within the Tour itself, drawing on contemporary scholarship in the history and theory of cartography in parsing the text’s various, and often competing, spatial strategies. Along the way, I wish to take seriously in particular what it means to call this geography reader children’s literature. In interrogating another fin-de-siècle cultural monument, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Jacqueline Rose has asked of it, ‘Spectacle of childhood for us, or play for children?’ (Citation1993, 33). The answer to Rose’s question, in the case of the Tour, is in some ways overdetermined by its national-imperial ideology, didacticism, and moralistic sensibility. Yet as a cartographic narrative, the book is better described as disproportionate as well as diachronic: it incorporates a messier compendium of spatial practices than that implied by the explicit task of cartographic literacy. Bruno’s Tour features characters who make use of topographical plans in order to travel across land and sea. But as we’ll see, these printed, increasingly mass-produced maps rubbed shoulders with conflicting cartographic logics within the text. And it was as the Tour itself travelled across France’s colonial possessions that the spatial contradictions already evident within it came into even clearer view.

Bruno and Third Republic Geographical Thought

‘L’itinéraire d’André et de Julien commence au début de l’automne (“par un épais brouillard du mois de septembre”, qui ne s’en souvient?)’ (Ozouf and Ozouf, 294). Like many entries in Nora’s Lieux de mémoire, Jacques Ozouf and Mona Ozouf’s contribution helped to establish what it purported to describe. The rhetorical parenthetical quoted above calls a certain public into being; but it also presumes, rather than analyses, the book’s monumental status within the French ‘mémoire collective’ (293). All the same, it effectively demonstrates how the 1877 reader fixed republicanism as the telos – necessary and unquestionable – of French history. The Lieux de mémoire chapter focuses on the major changes between the original 1877 and the 1906 revised and secularized edition, when all religious language (Dieu, ciel) and settings (Notre-Dame de Paris, Chartres) were quietly removed. Already in 1976, Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen had claimed that Fouillée represented dialect in the Tour as an inevitably disappearing reality, helpless before the triumphant victory of standardized French. Making ‘peasants into Frenchmen’ within the borders of metropolitan France – alongside a near-simultaneous building of empire abroad – would require the elucidation of a national identity (and, specifically, republican one) that could be exported, in theory, throughout the world (Weber Citation1976).

The historian John Strachan has sought to complicate this view of republican hegemony in the Tour, arguing that ‘republican modernity embodied a perpetual negotiation between new and old forms of patriotism and identity’, between the Romanticism of Rousseau and Michelet and a post-1870 spirit of ‘patriotisme départementale’ (Citation2004, 98). This emphasis on negotiation more than imposition is notable as well in Dana Lindaman’s sophisticated analysis of the rise of a ‘geographic sensibility’ in modern France (Citation2008, 5). As Lindaman points out, the Tour was indebted to contemporary atlases in its narrative structure as well as in its pedagogical motivation. It should thus be understood within a developing context of both professionalized academic geography and the popularization and diffusion of such knowledge in primary and secondary schooling.

Kory Olson’s recent study on the Third Republic’s mapping of Paris and its surroundings reads the textbook as one of many tools through which the government promoted cartographic literacy. Superimposing provincial references onto contemporary departmental divisions, the reader would ‘help bridge the gap between an older, provincial vocabulary with the new push to republicanize the French curriculum’ (Citation2018, 67), all of which ‘played a pivotal role in helping the Third Republic to get to know its territory better and allowed its citizens to understand the maps in the real world’ (131).

Before turning to the Tour itself, it is worth briefly reprising this conjuncture through the lens of two thinkers, both (in quite different ways) central to Third Republic geographic theory and pedagogy: Paul Vidal de la Blache and Elisée Reclus. A professor at the École Normale Supérieure and later the Sorbonne, Vidal was originally a historian who hoped to promote a less positivist and more theoretical approach to geography than that of his colleagues at the university level. His was part of a broader attempt to develop a republican cartography that would dislodge Paris from its status as centre, and his prolific career helped to establish a region-based framework based on local cartographic research.

Vidal’s 1903 Tableau de la géographie de la France, the first volume of Ernest Lavisse’s Histoire de France, explained national geographical divisions by what Vidal was later to call genres de vie (Citation1911a, Citation1911b). Differentiated by regions of reciprocal interest, this method would illuminate the intertwining of humans and environment, nature and culture, landscape and identity. Each ‘region’ shared a certain level of homogeneity, making it a useful scale for scientific analysis. This was all the more important as geography was seeking a legitimate position for itself as a social science. Indebted to Lamarckian understandings of adaptation, Vidal saw organisms as mutually developing within their environment, a multidirectional process that could explain organisms as equally natural and social. In general, the Vidalian school sought to avoid a strict environmental determinism; instead, he and his colleagues and students asked how political-administrative and ‘natural’ divisions (such as mountains, rivers, and basins) worked together to influence historical change.

Vidal’s own method was narrative rather than synthetic; the Tableau tended to begin its chapters with visual scene-setting before plunging into descriptions of geological formations, landscapes, and demographics, as well as geology. His prologue, for example, took up the language of the visual arts, not only that of the landscaper but also of the portraitist: ‘J’ai cherché à faire revivre […] une physionomie qui m’est apparue variée, aimable, accueillante’ (Citation1903, 4). The rest of the book devoted close attention to toponymic detail, describing a ‘vocabulaire géographique’ of place names forged by the mobile currents of merchants and pilgrims, one leading to a ‘géographie populaire’ that could serve as fodder for legend (169). Culture might influence history and geography as much as the other way around.

Vidal’s retrospective concluding chapter glanced back to the ‘vie d’autrefois’ (380) and its regular temporal rhythms. Indeed, the Tableau tended to foreground the persistence of a rural and provincial France above all. Lamenting the continuation of a binary Paris-Province division, Vidal argued all the same that ‘la grande révolution qui a transformé la vie moderne’ was not the French Revolution, the ‘révolution politique’, but rather the transportation revolution of the mid-nineteenth century (380). The Tableau’s flexible understanding of borders and regions avoided the ideological implications of proposing certain (political) borders as ‘natural’. Its focus on communication networks and economic developments, as well as physical geography, nevertheless tended to consign politics to a secondary position.

In addition to the regional monographs, beginning in 1885, Vidal oversaw the dissemination of cartes murales to be used in schoolrooms throughout France. Replacing the method of rote memorization, these visual tools served an explicitly didactic purpose, helping French schoolchildren grow accustomed to and familiar with synoptic views of national and colonial territories. Here the political implications of Vidal’s process are clearer: students’ education into the kind of abstract thinking that was implied by the two-dimensional, Euclidean map taught them to imagine political borders as objective, as well as to situate their own identity in relation to the sites depicted.Footnote5

Vidal and other humanistic geographers of the Third Republic sought to distance their work from the overly practical and state-sponsored geography of exploration. As a member of the Parisian École coloniale’s steering committee, however, not to mention the dissertation advisor for a number of theses on colonial geography, Vidal oversaw the research of a younger, influential generation of colonial geographers, some of whom would take up posts at the University of Algiers and continue the legacy of academic geography through the era of twentieth-century decolonisation (Berdoulay Citation1981; Singarévalou Citation2011). His own studies of southwestern Algeria’s ksour region had the effect of flattening and de-historicizing the genres de vie of the Algerian fellah.Footnote6 As much as Vidal sought to denaturalize borders by analysing the interpenetration of physical geography, culture, and history, his commitment to contingency and flexibility came under strain as France’s colonies were incorporated into the regions of metropolitan France.

Worlds apart from Vidal’s approach would seem the cartographic vision of Elisée Reclus, anarchist and autodidact to Vidal’s republican and consummate institutionalist. As Kristin Ross has argued, the very triumph of Vidalian geography (in its most significant descendant, the Annales School) was enabled in part by suppressing Reclus’s anarchist geography (Citation1988, 54). While Vidal found the rural and provincial scales to be most authentically French, Reclus claimed, ‘C’est dans les grandes villes, surtout à Paris, que se montre le Français par excellence’ (Citation1885, 49). And if Vidal’s Tableau featured the topographic survey as the key pedagogical tool for geographical knowledge, Reclus was more drawn to the technology and aesthetics of the globe. Spatially undistorted and intuitive to grasp – even for a child – a globe could also enable reader-learners to understand themselves as part of a single human community, undivided by nations or empires. This was the impulse behind Reclus’s intriguing and ultimately failed project of a massive globe for Paris’s 1900 exposition. With a cost swelling to 20 million francs, it was originally envisioned to make up a circumference of 523 meters. The globe would be displayed not as leisure spectacle – like the exposition’s other baubles and pageants – but as a project of ‘human emancipation’ (Alavoine-Muller Citation2003).

There was also an ecological focus to Reclus’s geography; as Göran Blix (Citation2019) has recently shown, all Reclus’s geographical writings, from the early La Terre (1868–69) to his major, multivolume La Nouvelle géographie universelle (1876–94), stressed a continuum between the human and the natural worlds, as between utility and aesthetic beauty. For Reclus, geography was necessarily internationalist: as Ross glosses his cartographic imaginary, ‘national perceptions can only create obstacles to a study of the natural environment which spills, necessarily, across national, even continental borders’ (Ross Citation2016, 134).

Yet as we saw above, Vidal too shirked political and administrative divisions in his focus on regions as the epistemological keystone of geographic knowledge. The two geographers converged, as well, in their regionalist rebuke to administrative departments, and in their attempt to distinguish such partitions from topographic and geological pays. If Vidal used ominous language like ‘toile d’araignée’ and the ‘tentacules d’un polypier’ (380) to describe the etching of networks of roads and railways onto the landscape, in his Nouvelle géographie universelle Reclus too opposed ‘political’ divisions (modern départements as much as ancien regime provinces) to ‘natural’ ones. He argued a living, breathing geography was to be found only in what he called pays naturels. By looking at physical divisions like mountains, rivers, and uneven terrain, he might account for the multiplicity of languages and ethnicities in a country like Switzerland (Reclus Citation1885, 539; see also Ozouf-Marignier Citation2000).

In discussing Third Republic approaches to geography, Lindaman argues that Bruno’s Tour was indebted to the rise of the new geography in its Vidalian strain: he offers a useful distinction between Bruno’s Vidalian text and Arthur Rimbaud’s Reclusian geography. All the same, as we have seen, there was much that Vidal’s and Reclus’s most important written works shared. Both were narrative as much as pictorial forms of mapping. Both sought to embed their spatial understanding within a temporal and historical framework. And in seeking to make space for geographical contingency, both sought to distinguish themselves from environmental determinism as much as from ethnonationalist ideology. While Bruno’s Tour recalls the unsettled status of the region in Vidal’s Tableau, its insistence on forging a notion of community across multiple scales is much more reminiscent of Reclus. The following section continues to tease apart these respectively Vidalian and Reclusian elements. Where the Tour would diverge from both figures was in staking a claim for the material reality of administrative borders – even to the extent of naturalizing contingent, political transformations in French history and geography.

Mapping as Knowing

The preface to Bruno’s Tour proposed that an imaginative, immersive, and kinetic account of the voyage of the two young Lorrains would allow students to ‘pour ainsi dire voir et toucher’ their country (Citation1985, 4). Within the context of more scholarly approaches to geography, the Tour’s spatial representation of knowledge was organized through haptic encounters and characterized by uneven temporality – both of which coexisted uneasily, I wish to suggest, with its developmental view of the child and its didactic aims. Borrowing features from the compagnonnage tradition, adventure fiction, national epic, and novels of formation and initiation, the book is generically ambiguous to a striking degree.Footnote7

The first chapters of the Tour describe the recently orphaned brothers’ departure from Phalsbourg. Their mother is long dead; their father was first wounded in the siege of Phalsbourg and subsequently perished in a fall from a scaffold. The ‘loss’ of Lorraine to the Germans is thus figured less as conjunctural crisis than as the slowly mouldering trauma of a wound. Julien and André head off in the general direction of Marseille to seek help from an uncle. When they finally catch up with him, the story cannot yet conclude (and not only because it is cartographically incomplete): as law-abiding republicans, they will have to return to ‘regularise’ their situation in Lorraine and declare their intention and desire to be French.

Each chapter, then, illustrates a different part of the country, and each region or locale is yoked to a lesson: a moral nucleus to be extracted from the narrative shell. Sometimes André ventriloquises the schoolteacher’s role – the livre de maître version of the reader – in signalling to Julien just how he should interpret the people, places, and phenomena that they encounter. As André marvels, for instance, at the ‘belles’ and ‘commodes’ machines that have replaced manual labour in the Vosges paper mills (‘je m’en suis revenu émerveillé de l’industrie des hommes’), the chapter’s lesson echoes his conclusion: ‘Si vous parcouriez la France, que de merveilles vous admireriez dans l’industrie des hommes, à côté des beautés de la nature!’ (45).

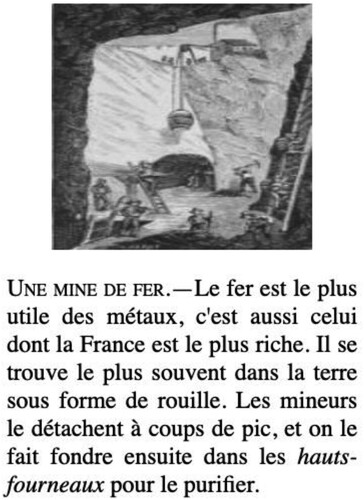

Compared to Vidal’s Tableau, the Tour is rather more sanguine about the effects of modern industry on national progress. Industrial and natural ‘richesses’ occupy the same plane, from farm animals and local flora and fauna to Europe’s largest factory in Creusot, where the children ‘admire’ the child labour underway in the furnaces (see ). (The lesson here is not to contest exploitation but rather to cultivate ‘sympathie’ towards exploited workers [115–6]). When the children arrive in Paris, in turn, they are treated to a glimpse of urban modernity, where time passes more quickly and the lights are never turned off. But eventually a more Reclusian understanding of the relation between capital and nation materializes: ‘Paris est l’image en raccourci de la France, et son histoire se confond avec celle de notre pays’ (283). Importantly, however, Paris is not the endpoint but a mere waystation along the circumference of a loop that ends back in the provinces. Within this narrative logic, Bruno’s vision of expanded fraternity takes shape in the aid the brothers receive from a range of characters, from Fritz the forest ranger to Étienne the shoemaker. The latter advises André and Julien that when they, in turn, should meet ‘un enfant de la France en danger, vous l’aiderez et ainsi vous aurez fait pour la patrie ce que nous faisons pour elle ajuourd’hui’. (14) Anne-Marie Thiesse has shown how a fin-de-siècle celebration of provincial France emerged from anxieties ensuing from Prussian defeat. Combined with lingering fears of urban unrest and rural exodus, these anxieties were siphoned into the prized petite patrie that would mediate between family and society (Citation1997, 3–10). Here, revanchisme in the aftermath of defeat takes shape less through arms than moral instruction. Julien and André’s biological parents were to be replaced not only by the nation as parental figure but, in a model of proliferating ties of kinship, by its various petites patries. If the French Revolution had propounded a ‘new family romance of fraternity’ (Hunt Citation1992, 53) to replace the one dominated by patriarchal royalism, the Third Republic was to offer its own distinct brand of brotherly love.

When the boys’ wagon tumbles over in a blast from the mistral (an opportunity to learn about regional atmospheric diversity), the adventure not only invites a lesson about the utility of a republican caisse d’épargne but also enables Bruno to speed up and slow down the narrative pacing: Julien’s foot is wounded and, no longer able to continue on foot, they hurtle through the next leg of their journey by rail. As the spatial scales in the textbook range unsystematically between province, region, department, and pays, its various rhythms are enabled by the brothers’ distinct modes of transport and travel, from foot to covered wagon, from train to ship. In turn, lessons about geology and physical geography are linked to the historical departmental maps that are described within the plot, and which the brothers consult along their way. Hanging on the wall of Fritz the forest ranger’s cabin, for instance, is ‘une de ces belles cartes dessinées par l'état-major de l'armée française, et où se trouvent indiqués jusqu'aux plus petits chemins’ (170). The Carte de l’État-Major was a military-run state project launched in the post-Napoleonic period, and updated throughout the century through a new and expanding workforce, the Corps des ingénieurs-géographes. While the first sheets were sold in 1833, the project was completed only in 1875, just as the commercial sector was gaining priority over military needs.Footnote8 Within the Tour, the map is not exactly a luxury object, though neither is it quite a mass commodity. André cannot take it with him but dutifully notes down certain landmarks from this map to guide his way: ‘un groupe de hêtres’; ‘un roc à pic’; ‘une tour en ruines’ (17).

On the other hand, André’s younger brother Julien, ever the loyal student, may be a refugee but insists on carrying around his own school textbook under his arm, including its own small-sized maps. At one point another helping father-figure points Julien to one of those maps located within the reader in order to instruct him on the geography of Lyon (151). The boy announces, pleased, that he will become the top student at school upon his return, since he’ll know his French geography better than anyone (94). Such a mise-en-abyme encourages student readers to use the Tour as their own cartographic document, with Julien’s process of instruction as model.

Yet the two-dimensional, topographical map is by no means the Tour’s prevailing cartographic mode. In the letters that Julien writes to his friend Jean-Joseph, telling of their sea voyage up the eastern coast of France, his narration takes on elements of the genre of the periplus, a tradition that can be traced back to the classical Mediterranean world. These usually anonymous manuscripts would note the most important features of the terrain, customs of the native populations encountered, and other details likely to be of interest or use for travelling merchants’ purposes.Footnote9 Taking the form of a sailor’s log-book, these verbal ‘maps’ were less than practicable for overseas maritime voyages. But they did offer another kind of pragmatic spatial practice; they could, for instance, serve as a guide for other travellers in later voyages, as well as a record of one’s own journey and the specific temporality of a maritime passage. Such diachronic elements of Bruno’s text, particularly the attention to dangers and threats one might find along a journey, rub against the synchronic vision of the earth seen from above, as when the brothers peer over the administrative Carte de l’État-Major: a surveyor's logic—the optical illusion that Donna Haraway famously called “the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere” (Haraway Citation1988: 581)—when gazing onto a scenic prospect.Footnote10

Art historians, literary critics, and other scholars have long pointed out that such a logic is part of a longer tradition of European landscape ideology. As the anthropologist Tim Ingold has put it, ‘We treat the landscape as a view, and imagine that we see the world in pictures’ (Citation2015, 41), along the way eliding the lives and labour embedded within these (often rural or provincial) sites (Barrell Citation1980; Cosgrove Citation1998). Ingold has sought to denaturalize such presumptions in part by distinguishing what he calls the ‘Kantian traveller’ from the ‘walker’. The former picks up data and fits particulars into abstract conceptual frames, travelling across a given surface:

The traveller, is, in effect, a mental map-maker. And as is the rule in cartography, his observations are taken from a series of fixed points rather than en route from one place to another. His moves serve no other purpose than to carry himself and his equipment – that is to say, the mind and its body – from one stationary locus of observation to another. (Citation2015, 47)

To a significant extent, then, cartographic literacy – knowing how to read a modern map – is certainly not their only, perhaps even not the best, tool for developing spatial awareness. Often, the chapters begin with a panoramic description of the landscape before the children’s eyes. In late-nineteenth-century France, panoramas were becoming a commercial obsession – but also operated on rather different cartographic and epistemological bases. Vanessa Schwartz has shown how Paris’s ‘O-Rama craze’ (Citation1998, 149–76) contributed to post-1870 revanchism by cultivating patriotism and nationalistic attachment to scenes of battle. Yet the politics of the panorama were often not so straightforward: they often operated as urban spectacle and consumer commodity rather than seeking to cultivate patriotic citizens per se. While in some ways the panorama reflected the surveyor’s logic by placing the viewer at the centre of an observational regime, the hierarchy of meaning that ensued from that centripetal logic could also be troubled by the fact that spectators might move around; might become more or less attentive or distracted; might engage in communal practices as much as in solitary looking.Footnote11

This tension is at work in some of the children’s encounters with difference throughout the Tour. When the brothers, for instance, meet other characters who speak in the ‘patois du Midi’, they are disappointed not to be able to learn about silk cultivation from them. Inability to wield standard French is coded as a national pedagogical failure (‘C’est que tous n’ont pas pu aller à l’école’ – at least not yet [165]), as well as a denial of justice for Julien and André’s own learning and growth. Here the Tour aligns with another post-1870 tale of the ‘provinces perdues’, Alphonse Daudet’s ‘La Dernière Classe’, which also nods to the Third Republic’s policies of standardized French. In Daudet’s story, the schoolteacher Monsieur Hamel trumpets the French language as ‘la plus belle langue du monde, la plus claire, la plus solide’ (Daudet Citation1986, 584). Monsieur Hamel is about to be dismissed to clear the way for obligatory Germanophone instruction, and his final lesson includes a rousing injunction for his students to retain their language as a mode of resistance when ‘un peuple tombe esclave’ (584). While the Tour construes provincial dialects and local languages as relics of the past, for Daudet it is standard French that is figured as minoritized and needing to be rescued – in both cases by schoolchildren. And it is French citizens (not, needless to say, its own colonial subjects) who are colonized, even ‘enslaved’.

To return to the Tour, when the brothers finally reach the port of Marseille, the relation between text and image in the textbook only underscores the racial and colonial implications of its didactic approach. It is in the caption under another visual engraving that we learn that Marseille ‘fait un très important commerce avec l’Algérie et la Tunisie’ (185). The city’s human diversity is addressed, however, not in the diegetic text but instead through its illustrations, including a diagram portraying a racialized hierarchy of humanity with a list of ‘red’, ‘yellow’, ‘black’, and ‘brown’ races (the ‘Whites’, at the summit, embody human ‘perfection’ [184]). The illustration reinforces Françoise Vergès’s claim that ‘the glorification of Republican ideals, ideals inherited from the French Revolution’ developed in mutual interrelation with ‘the denigration of the foreign, the belief in racial superiority’ (Citation2013, 253), which not only mediated notions of Frenchness but also tempered the universalizing potential of a fraternal contract that might extend beyond biological kinship.

In the Tour, this sleight of hand required excising France’s colonies from the diegetic structure almost entirely, as sites outside metropolitan France remain as a kind of colonial unconscious within this tool of Third Republic geography education (at seven and fourteen, respectively, Julien and André represent the origin and endpoint of primary school). The colonies would rear up again elsewhere, however: not only in a few chapters on France’s colonies appended to the 1906 revised edition, but also in Augustine Fouillée’s follow-up school reader Les enfants de Marcel (1887). There a different set of cartographic parallels, specifically those drawn between the provinces perdues and Algeria, were enlisted in the interest of a new geographical and pedagogical imaginary.

Les enfants de Marcel too begins in the aftermath of war, as the sergeant Marcel and his eldest son Louis are retreating from Alsace into Switzerland. There they are taken in by the young Rose and her grandfather Stephen Zurog, whose advanced age of 98 enables him to recount his participation in the French Revolution. His tale carefully balances a sense of French exceptionalism with an ominous warning of the excesses of the Terror. Lines like the following seem, all the same, to have a rather more recent popular revolt in mind: ‘Aujourd’hui, la nation est souveraine; c’est ce qui fait que, de nos jours, les révolutions sont des crimes sans excuse’ (Bruno Citation1887, 32). Father and son eventually make it back to a town outside Bordeaux, where Louis’s grandmother has also escaped from Alsace and is awaiting them with her four younger grandchildren. A dozen years into the Republic, reaching the position of a fonctionnaire represents a French schoolchild’s greatest imaginable success, here gendered along new axes: Marcel takes up a job as a post officer, while his daughter Lucie becomes a telegraph operator. France’s disparate regions can be united through the temporal and spatial collapse enabled by modern technologies. Indeed, it’s through a telegram that the family eventually learns that they have inherited a property in Constantine, Algeria. Marcel’s Alsatian brother-in-law, Christian Herbart, had settled there after 1870, having taking advantage of the French government’s offer of land to soldiers who had served in the war. ‘Famille nombreuse, patrie puissante!’ (259) Christian writes; yet despite his own embrace of Third Republic natalism, his two children have died, so colonial inheritance protocol intervenes. Scrutinising yet another cartographic object – a property map, or ‘plan du terrain’ (223) – Marcel compares the diagram with the sheet of costs and balances that accompanies it, reasoning that the land, now colonists’ property, should stay within the family. So they pick up and move to Christian’s farm – which he had dubbed ‘Petite-Alsace’. The grandmother ‘se sentit tout émue’ upon arriving, ‘comme si elle revenait dans son pays natal, dont elle était maintenant si loin’ (255). In this particular version of imperial nostalgia (Rosaldo Citation1993), the lost homeland is redeemed through the settler colonialist’s affective attachments and imaginative intimacies, all bolstered by a cartographic vision as iterable and replicable as the blank spaces of a Conradian map.

In narrating and narrativising French geography, in collapsing childhood development onto educational formation, the Tour and Les enfants de Marcel alike portrayed children’s attempts to make sense of their world in the aftermath of war as well as personal and familial trauma. Cultural obsessions with childhood and the child, Lee Edelman has polemically argued, are not only a symptom of late capitalist anxieties but set the terms of politics as such. In other words, ‘the fantasy subtending the image of the Child invariably shapes the logic within which the political itself must be thought’ (Citation2004, 2). In this sense, too, the children’s journeys portrayed in these textbooks represented cartographic encounters as a source of epistemic uncertainty, far more than mastery – even as such ideological contradictions find an illusory resolution in the solace of sentimental fiction’s narrative closure.Footnote12

The Tour on Tour

The borders of Bruno’s Tour in some ways belied, in others only highlighted, its entanglement with broader geographical scales. This fact becomes all the more evident once we consider the peregrinations of the reader itself far beyond the Hexagone.Footnote13 To begin with, the Tour quickly became an international commercial success; it was, for instance, dispatched across the Channel to be deployed for English schoolchildren learning French. As Patrick Cabanel has shown, the Tour also made its way to Mexico and to Spain, where geography textbooks commissioned by educational authorities borrowed copiously from the Tour’s structure – and even transplanted specific plot points – into their own versions of national tours.Footnote14 In Sweden, Nobel winner Selma Lagerlöf’s geography reader and children’s classic The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (1906) has long been associated with Bruno’s Tour, even if Nils’s fantastical elements contrast with the Tour’s more realist register (Julien ‘savait bien qu’il n’y a pas de fées’ [34]). Lagerlöf’s embrace of fantasy, her rather more pliant didactic approach, also imply a distinct view of childhood: one whose operative mode is less national pride or triumphalist expansionism than something like wonder.

Yet the Tour was also being republished, reedited, and adapted as France was conquering ever more colonial territories, and as citizen-subject distinctions forged in Algeria, especially in the aftermath of differential minority treatment through the 1870 Crémieux decree, were setting a standard for France’s other settler colonies (Saada Citation2012, esp. 95–120; Samuels Citation2016, 73–94). As Alice Conklin (Citation1997) has argued, political and intellectual elites towards the end of the century were coming to recognize that the stability of the French empire would increasingly rest not on assimilation but on locally ‘adaptive’ educational techniques. This was a theory that rested, as we saw above, on fin-de-siècle ‘scientific’ racism as it was cementing racialized hierarchies of intelligence and capacity. In this context the Tour’s coinciding techniques of geography, education, and literary narrative proved a potent textual contribution to the mission civilisatrice.Footnote15

In French Indochina, civil servant Jean Marquet’s Les Cinq Fleurs: L’Indochine expliquée, a French reader destined for franco-indigène schools, also recounted the adventures of brothers (this time five Annamite boys) travelling across French Indochina’s five countries. Explicitly inspired by Bruno’s Tour, this reader too included maps at various scales as well as narrative cartographies. Like the Tour, though unlike other French-language readers in colonial schools, it was composed of a single narrative, rather than a compilation of literary excerpts. Within the narrative, the brothers’ journey is motivated by aims more commercial than patriotic: they are to track down new tea leaves to help their father in his ailing business. Before their journey begins in earnest, however, a village teacher gives them a geography lesson, one that unfolds according to the logic of a list: provinces and capitals, local animals, and economic resources are all tabulated. As Marie-Paule Ha has argued, rather than ‘Gallicize the colonized’, Marquet aimed to ‘re-orient students back to traditional cultures and societies, which were reconfigured in terms that concurred with the imperative to maintain French hegemony’ (Citation2003, 114). The author’s view of what constituted these traditions was tendentious: he was a fervent supporter of Vietnamese colonization of Laos, and Laotians are notably absent from the brothers’ trajectory and encounters. The descriptions in Les Cinq Fleurs linger over colonial infrastructure far more than physical or geological characteristics. The brothers witness mines, factories, and canals as they travel via trains, steamships, and even an airplane, making for a spatial and scalar tempo rather more precipitous than Bruno’s Tour. It all builds to a glorification of French modernisation: ‘Et quels progrès, réalisé en un espace de temps à peine égal à la vie d’un homme’ (Marquet Citation1928, 160). In this cartographic narrative, that is, exploring and traversing the terrain is not necessarily meant to lead to a sense of ownership and pride. Colonial divisions tended to undermine rather than cement the relation between spatial knowledge and cultural or national belonging.

Fraternal affection; a didactic approach to spatial knowledge; latent anxieties regarding cultural and ethnic heterogeneity: these features can be discerned, in different ways, in an even earlier text inspired by the Tour: Moussa et Gi-gla. Histoire de deux petits noirs (1916). I’ll linger at greater length over this adaptation, given how indebted it was to the Tour, not only in its broad narrative frame but even in its rewriting of specific scenes and plot points. Published by colonial educators Louis Sonolet and Auguste Pérès for use in French West Africa, the book, like Les Cinq Fleurs, was directed to French-speaking students outside the metropole. If Émile Levasseur’s Himly report of 1871 warned that France’s enemies had been better able to navigate French terrain thanks to their knowledge of geography, Senegal’s lieutenant governor Camille Guy had concluded his own 1902–3 inspection of schools in French West Africa with a report expressing concern that Senegalese students knew French geography and history better than their own.

Moussa et Gi-gla would be used in regional schools throughout the federation into the 1950s (Calvet Citation2010). It tells of a young boy, Moussa, from Sudan (modern-day Mali), whom the French businessman M. Richelot hires to accompany him on his business trip down the Niger. He eventually takes another child, Gi-gla from Dahomey, into the scheme, and together the three travel across the federation of colonies and territories of French West Africa, including to the capital of Dakar. Along the way Monsieur Richelot instructs the boys on ‘their’ geography, together with the myriad ways French colonization has benefited Africans. Each time a new locale is mentioned, a footnote refers a reader to a topographical map located in the middle of the book. But as made evident in Sonolet and Pérès’s original preface, the motivation for publishing the schoolbook incorporated an unabashedly Francocentric model of the African schoolchild’s geography education:

… lui faire connaître et aimer la France, lui montrer notre pays comme le plus glorieux, le plus avancé en civilisation, le premier tout autant par le courage de ses soldats que par les mérites de ceux qui l’ont illustré, particulièrement de ceux qui ont apporté en Afrique occidentale la prospérité et le progrès. (qtd in Trnovec Citation2018)

In Sonolet and Pérès’s version of the fraternal contract, Moussa’s companion is a non-biological ‘brother’, Gi-gla, another orphan. (Part of the plot intrigue, however, involves Moussa’s long-lost older brother Tiékoura, whom he meets again, finally, in Dakar: family separation is resolved not by return to the native village but in the very heart of the cosmopolitan colonial capital.) At other points Sonolet and Pérès seem to have lifted scenes straight from the Tour, as in Julien and André’s encounter with a drunkard: ‘Mon Dieu! pensait André, que l'ivresse est un vice horrible et honteux!’ (Bruno 68); in Moussa et Gi-gla, it's Monsieur Richelot who warns the two boys, ‘Vous voyez, mes enfants, à quoi peut conduire l’ivrognerie’ (Sonolet and Pérès Citation1916, 58).

In Bruno’s Tour, the ships that carry Julien and André up the eastern coast of France bear the name of several French provinces. Moussa and Gi-gla, for their part, travel to Grand-Bassam in the Côte d’Ivoire on a boat named the Atlantique. The name recalls on the one hand the tales of colonial adventure clogging the fin-de-siècle market for children’s books in France; on the other, the transatlantic slave trade. The ship is led by a pilot named ‘Prosper’, with its own Shakespearean resonances for the colonial shipwreck narrative (this one with no Césairean Caliban).

In Les enfants de Marcel, the young Louis had been a mouthpiece for the French teacher: in Fouillée’s pedagogical fantasy, the many years of instruction at school are at once temporally collapsed and ideologically justified. Louis recounts to his siblings how all of Algeria was, prior to colonization, a site of as-yet undeveloped resources necessitating a handshake between empire and capital: ‘mais qui a fait cette rouet carrossable dans ce pays perdu et sauvage? Ce sont les ingénieurs de la France’ (246). Algeria had to be conquered, too, for ‘Alger, reprit Louis, était encore au commencement de notre siècle un repaire de pirates’ (233).

As for Moussa et Gi-gla, Sonolet and Pérès stressed in their preface that they wished to make schoolchildren into ‘des Français heureux et fiers d’être’ (3). But what would it mean for these children to be ‘French’? Metropolitan French textbooks’ use of the possessive ‘our’, Gilles Manceron has noted, encouraged students to imagine themselves as ‘the personal possessors of the colonial territories, and therefore personally concerned by their future’ (Citation2013, 124).Footnote16 Moussa et Gi-gla too was meant to forge a regional-colonial unity across linguistic and cultural diversity, in a way that bore certain similarities to the regionalism we saw above, in Vidal and Reclus as much as in the Tour. But unlike in Bruno’s Tour, where the pronoun ‘nous’ is ubiquitous, Moussa et Gi-gla is notable for the relative absence of the first-person plural. The lines between teacher and student, writer and reader, are more fractured; its attention to the spatial dynamics of French West African colonialism, including the authorities’ industrial exploitation of African natural resources, illuminates the narrative distance between the young students and the ‘Blancs’, whose ‘achievements’ have to be pointed out to the children, lest they fail to recognize them.

Finally, in focusing on African geography and history, together with a Francocentric mission civilisatrice, Moussa et Gi-gla skates over any details of the French Revolution that could imply that freedom might have to be achieved through violent revolt. In this its tropes of ideological assimilation, if not exactly French acculturation, operate according to what Rob Nixon has called a ‘spatial amnesia’, including the environmental exploitation of what he calls ‘unimagined communities’ that are nonetheless vital and sustaining to the nation-state (Citation2011, 151). And to the empire, we might add: a problem that French West African schoolteachers themselves would have to wrestle with in the classroom when teaching with Moussa et Gi-gla and other metropolitan-based textbooks for decades to come.Footnote17 For instance, Sonolet and Pérès represent Moussa as a free agent in his own journey: ‘Je serai très content de voyager. J’aime beaucoup voir du pays. Ça instruit’. M. Richelot’s generosity includes the ‘opportunity’, as he tells his charge, to ‘dresser mon lit, préparer mes vêtements, blanchir les souliers et le casque, faire des commissions’ (2). Like Julien and André, Gi-gla becomes a farmer at the end of the book, while Moussa joins those tirailleurs sénégalais (‘L’un défendra son pays, l’autre le cultivera’ [139]) who would take their place at the centre of racial and anti-colonial politics in wartime and interwar France. Before their ‘education’ is complete, however, an extended gloss on the relation between ‘droit’ and ‘devoir’ (the subtitle of the Tour and the words with which that textbook ends) describes a division of labour in which the colonized subjects will ‘help’ the white populations by serving them, cultivating the land, and fighting for France. The colonizers will take charge of ‘instructing’ and ‘civilizing’. Unsurprisingly, Gi-gla has some difficulty grasping this ‘lesson’: he asks for it to be repeated several times (255-6). If the colonial fantasy, in Frantz Fanon’s terms, requires the colonized subject to ‘offer no ontological resistance’, this is one moment at which those fantasies stretch to the breaking point of narrative credulity and ideological contradiction.Footnote18

Conclusion

In a French imperial context, topographical maps could endow metropolitan citizens with the capacity to scrutinize ‘their’ territory in detail. In what Matthew Edney has characterized as the ‘irony of imperial mapping’, restrictions on cartographic access led to a ‘marker of difference between the imperial community, able to see the land they ruled, and the actual inhabitants, who were denied such a comprehensive and empowering perspective’ (Edney Citation2009, 170).Footnote19

Moroccan-French artist Bhouchra Khalili’s recent Mapping Journey Project (Citation2008–2011) can be read as a sustained aesthetic engagement with the irony of imperial mapping. It is composed of a series of videos showing individuals tracing their migratory journeys throughout the Mediterranean in permanent marker, while narrating their movements from one place to another. The project offers a rebuke to the cartographic impositions of national surveillance systems, legal and media scripts, and international border control. It is a reproach, too, to the state-sponsored drawing of borders that have long taken shape in literature, geography textbooks, and the shifting space between them.Footnote20 We might understand Khalili’s imaginative effort to rewrite and redraw the imperial map, in other words, as a latter-day inheritance of cartographic experiments that were being forged in France’s Third Republic.

In tracing the travels of Bruno’s Tour, nevertheless, I have sought to disentangle the heterogeneous, often conflicting cartographic impulses located within the Tour itself, as well as beyond and around it. As we have seen, Julien and André’s embedded, haptic exploration of the terrain never culminates in any counter-hegemonic landscape aesthetics, while a bird’s-eye view of the earth below, in the case of Moussa and Gi-gla’s setting, might have illuminated the importance of safeguarding the land from the incursions of colonial and industrial modernity. Finally, a different kind of cartographic impulse emerges on the scale of reading and reception. As Robert Tally has proposed, writing and reading themselves can be understood as cartographic endeavours, ‘the ways and means by which a given work of literature functions as a figurative map, serving as an orientating or sense-making form’ (Citation2014, 114). In the case of the Tour, we might add: a disorienting form.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Victoria Baena

Victoria Baena is a Research Fellow in English & Modern Languages at Gonville & Caius College, University of Cambridge, where she is at work on her first book, a comparative literary history of the province-capital divide over the course of the long nineteenth century. Her essays have also appeared in Nineteenth-Century French Studies, Diacritics, ELH: English Literary History, and Victorian Literature & Culture.

Notes

1 For the classic study of geographical regimes of ‘space’ and ‘place’, see Tuan (Citation1977).

2 Born Augustine Tuillerie in 1833, the author separated in 1855 from a violent husband; she and her son (who would become the philosopher Jean-Marie Guyau) later lived with Alfred Fouillée, until the 1884 divorce law enabled her to marry him and become, as the textbooks noted, ‘Madame Fouillée’. See Cabanel (Citation20Citation07, 149).

3 For influential recent literary and historical theorizations of such intertwined histories, see Joseph-Gabriel (Citation2020), Wilder (Citation2020), and Saada (Citation2012).

4 See especially Bray (Citation2013), which engages with, among others, Michel de Certeau, Henri Lefebvre, and David Harvey, and Bell (Citation2018), which brings the work of Neil Smith and Johannes Fabian to bear as well.

5 For map-reading as instruction into abstract thought, see Jacob (Citation199Citation6, 193–4).

6 We might recall here Edward Said’s statement that the discipline of modern geography was born out of the effort ‘to dignify simple conquest with an idea’ (Citation1979, 216).

7 Patrick Cabanel has further placed the work into a tradition of what he calls ‘romans scolaires’ (Citation2007).

8 See Olson (435); Bigourdan (Citation1899).

9 The Periplus Maris Erythraei was a Greco-Roman text, written around the 1st century CE, which has enabled scholars to ascertain much of how the geographies of the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants were understood in the classical Hellenic world.

10 Mary Louise Pratt has characterized this as a ‘monarch-of-all-I-survey’ model: see Pratt (Citation1992, esp. 205–6).

11 For an introduction to the panorama’s epistemological presuppositions, see Katie Trumpener and Tim Barringer’s introduction to a recent (Citation2020) global historical survey of the panorama across literature and art.

12 See Eagleton (Citation2006).

13 I am thinking here of what critical geographers like Neil Smith (Citation2010) have called the production of scale: the ways in which uneven geographies are produced and reproduced, as contradictions rendered untenable at one scale are re-entrenched at another.

14 See Cabanel (754 ff.) for a detailed comparison of these texts on the level of plot and structure.

15 Rather than a ‘lieu de mémoire’, we might in this sense consider the Tour in light of a recent edited volume (Forsdick, Achille, and Moudileno Citation2020) on ‘postcolonial realms of memory’, sites or objects – both quotidian and symbolic – that secrete traces of France’s colonial past (and present).

16 I would like to thank Nick Harrison for pointing me to this resource.

17 See Labrune-Badiane and Smith (Citation2018) for a historiographical reflection on the complexities involved in tracing the histories of such encounters.

18 “L’ontologie, quand on a admis une fois pour toutes qu’elle laisse de côté l’existence, ne nous permet pas de comprendre l’être du Noir. Car le Noir n’a plus à être noir, mais à l’être en face du Blanc […] Le Noir n’a pas de résistance ontologique aux yeux du Blanc’ (Fanon Citation1952, 88–9).

19 For something of a qualification to this framework, see Sumathi Ramaswamy’s work on counter-cartographies of British India: in Tamil maps’ depictions of the ‘lost continents’ of Lemuria, she argues, ‘the mapping of lost continents and claiming possession of these as one’s own allow the colonial and postcolonial subject to aspire to mastery as well, but over disappeared placeworlds that European science and modernity had helped reconstruct through the modern technology of cartography’ (Citation2004, 222).

20 For ‘counter-mapping’, see Peluso (Citation1995), though for a reflection on indigenous challenges to state-centred boundary and resource representation to imperial mapping, see Craib (Citation2017).

References

- Alavoine-Muller, Soizic. 2003. “Un globe terrestre pour l’Exposition universelle de 1900. L’utopie géographique d’Élisée Reclus.” Espace Géographique 32 (2): 156–170.

- Barrell, John. 1980. The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting, 1730-1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, Dorian. 2018. Globalizing Race: Antisemitism and Empire in French and European Culture. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Berdoulay, Vincent. 1981. La formation de l’école française de géographie: (1870–1914). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale.

- Bigourdan, Guillaume. 1899. “La Carte de France d’après l’ouvrage du colonel Berthaut.” Annales de Géographie 8: 427–437.

- Blix, Göran. 2019. “Natura Magistra Vitae: Natural Pedagogy in Élisée Reclus's Histoire D'un Ruisseau.” Dix-Neuf 23 (3–4): 220–230.

- Bray, Patrick. 2013. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Bruno, G. 1887. Les enfants de Marcel : instruction morale et civique en action. Paris: Belin.

- Bruno, G. 1985. Le tour de la France par deux enfants (édition scolaire de 1906). Paris: Bélin.

- Cabanel, Patrick. 2007. Le tour de la nation par des enfants. Romans scolaires et espaces nationaux (XIXe – XXe siècles). Paris: Belin.

- Calvet, Louis-Jean. 2010. Histoire du français en Afrique. Une langue en copropriété? Paris: Editions Écriture.

- Certeau, Michel de. (1980) 1990. L’invention du quotidien, I: Arts de faire. Paris: Gallimard.

- Conklin, Alice Louise. 1997. A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Conroy, Melanie. 2021. Literary Geographies in Balzac and Proust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cosgrove, Denis. 1998. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Cosgrove, Denis. 1999. Mappings. London: Reaktion Books.

- Craib, Raymond B. 2017. “Cartography and Decolonization.” In Decolonizing the Map: Cartography from Colony to Nation, edited by James R. Akerman, 11–71. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Daudet, Alphonse. 1986. Oeuvres. Edited by Roger Ripoll. Vol. 1. Paris: Gallimard.

- Dupuy, Aimé. 1953. “Histoire sociale et manuels scolaires : les livres de lecture de G. Bruno.” Revue d’histoire économique et sociale 31 (2): 128–151.

- Eagleton, Terry. 2006. Criticism and Ideology: A Study in Marxist Literary Theory. New York: Verso.

- Edelman, Lee. 2004. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Edney, Matthew. 2009. “The Irony of Imperial Mapping.” In The Imperial Map: Cartography and the Mastery of Empire, edited by James Akerman, 11–45. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Edney, Matthew H. 2019. Cartography: The Ideal and its History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fanon, Frantz. 1952. Peau noire, masques blancs. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Flaubert, Gustave. 1973. Trois contes. Paris: Gallimard.

- Flaubert, Gustave. 1980. Correspondance. 4 vols. Paris: Gallimard-Pléiade.

- Forsdick, Charles, Etienne Achille, and Lydie Moudileno. 2020. “Introduction: Postcolonizing Lieux de Mémoire.” In Postcolonial Realms of Memory: Sites and Symbols in Modern France, edited by Achille, Forsdick, and Moudileno, 1–19. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Forsdick, Charles, and Jennifer Yee. 2018. “Towards a Postcolonial Nineteenth Century: Introduction.” French Studies 72 (2): 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/fs/kny005.

- Furet, François, and Jacques Ozouf, eds. 1977. Lire et écrire. L’alphabétisation des français de Calvin à Jules Ferry. Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

- Ha, Marie-Paule. 2003. “From ‘Nos ancêtres, les Gaulois’ to ‘Leur culture ancestrale’: Symbolic Violence and the Politics of Colonial Schooling in Indochina.” French Colonial History 3 (1): 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1353/fch.2003.0006.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–99.

- Harley, John Brian. 1989. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 26 (2): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3138/E635-7827-1757-9T53.

- Hunt, Lynn. 1992. The Family Romance of the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 2015. The Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

- Jacob, Christian. 1996. “Selected Papers from the 16th International Conference on the History of Cartography: Theoretical Aspects of the History of Cartography: Toward a Cultural History of Cartography.” Imago Mundi 48 (1): 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085699608592842.

- Joseph-Gabriel, Annette K. 2020. Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Khalili, Bouchra. 2008–2011. “The Mapping Journey Project.” Eight-channel video (colour, sound).

- Labrune-Badiane, Céline, and Étienne Smith. 2018. Les hussards noirs de la colonie: Instituteurs africains et ‘petites patries’ en AOF (1913–1960). Paris: Karthala Editions.

- Lindaman, Dana Kristofor. 2008. Mapping the Geographies of French Identity: 1871–1914. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Maingueneau, Dominique. 1979. Les livres d’école de la république 1870–1914: Discours et idéologie. Paris: Le Sycomore.

- Manceron, Gilles. 2013. “School, Pedagogy, and the Colonies.” In Colonial Culture in France since the Revolution, edited by Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, and Dominic Thomas, 124–131. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Marquet, Jean. 1928. Les cinq fleurs. L’Indochine expliquée. Hanoi: Direction de l’instruction publique en Indochine.

- Moretti, Franco. 1999. Atlas of the European Novel, 1800–1900. New York: Verso.

- Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Olson, Kory. 2018. The Cartographic Capital: Mapping Third Republic Paris, 1889–1934. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Ozouf, Jacques, and Mona Ozouf. 1997. “Le tour de la France par deux enfants: le petit livre rouge de la République.” In Les Lieux de Mémoire, edited by I. Pierre Nora, 277–301. Paris: Gallimard.

- Ozouf-Marignier, Marie-Vic. 2000. “Le Tableau et la division régionale. De la tradition à la modernité.” In Le Tableau de la géographie de la France de Paul Vidal de La Blache. Dans le labyrinthe des formes, edited by Marie-Claire Robic, 153–183. Paris: CTHS.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee. 1995. “Whose Woods are these? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Antipode 27 (4): 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.1995.tb00286.x.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi. 2004. The Lost Land of Lemuria: Fabulous Geographies, Catastrophic Histories. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Reclus, Élisée. 1885. Nouvelle géographie universelle. Vol. 2. Paris: Hachette.

- Rosaldo, Renato. 1993. “Imperial Nostalgia.” In Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis, 68–87. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Rose, Jacqueline. 1993. The Case of Peter Pan, or the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ross, Kristin. 1988. The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ross, Kristin. 2016. Communal Luxury : The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. London: Verso.

- Saada, Emmanuelle. 2012. Empire’s Children: Race, Filiation, and Citizenship in the French Colonies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

- Samuels, Maurice. 2016. The Right to Difference: French Universalism and the Jews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. 1986. The Railway Journey: The Industrialization and Perception of Time and Space. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Schwartz, Vanessa. 1998. Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Singarévalou, Pierre. 2011. “The Institutionalisation of ‘Colonial Geography’ in France, 1880–1940.” Journal of Historical Geography 37 (2): 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2010.12.003.

- Smith, Neil. 2010. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Sonolet, L., and A. Pérès. 1916. Moussa et Gi-gla : histoire de deux petits noirs: livre de lecture courante. Paris: Colin.

- Stoler, Ann Laura, and Frederick Cooper. 1997. “Between Metropole and Colony.” Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, 1–56.

- Strachan, John. 2004. “Romance, Religion and the Republic: Bruno’s Le Tour de La France par deux enfants.” French History 18 (1): 96–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/fh/18.1.96.

- Tally, Robert T. 2013. Spatiality. New York: Routledge.

- Tally, Robert T., ed. 2014. Literary Cartographies: Spatiality, Representation, and Narrative. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thiesse, Anne-Marie. 1997. Ils apprenaient la France. L’exaltation des régions dans le discours patriotique. Collection ethnologie de la France. Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

- Thiesse, Anne-Marie. 2021. The Creation of National Identities: Europe, 18th–20th Centuries. Leiden: Brill.

- Trnovec, Silvester. 2018. “Le manuel Moussa et Gi-gla et l’enseignement de l’histoire en Afrique Occidentale Française, 1900–1930: la construction d’une identité?” Journal Des Africanistes 88-1: 6–35.

- Trumpener, Katie, and Tim Barringer. 2020. On the Viewing Platform: The Panorama Between Canvas and Screen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vergès, Françoise. 2013. “Colonizing, Educating, Guiding: A Republican Duty.” In Colonial Culture in France since the Revolution, edited by Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, and Dominic Thomas, 250–256. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Vidal de la Blache, Paul. 1903. Tableau de La Géographie de la France. Paris: Hachette.

- Vidal de la Blache, Paul. 1911a. “Les genres de vie dans la géographie humaine: Premier article.” Annales de Géographie 20: 193–212. JSTOR.

- Vidal de la Blache, Paul. 1911b. “Les genres de vie dans la géographie humaine: Second article.” Annales de Géographie 20: 289–304. JSTOR.

- Weaver-Hightower, Rebecca. 2007. Empire Islands: Castaways, Cannibals, and Fantasies of Conquest. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Weber, Eugen. 1976. Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Wilder, Gary. 2020. The French Imperial Nation-State: Negritude and Colonial Humanism between the Two World Wars. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.