ABSTRACT

Drawing on the “new mobilities paradigm” and contemporary migration studies, this article offers an approximation to the experiences of mobility of María Juana Knepper y Trippel and her five daughters. Their staggered geographical trajectories from Flanders to the Pyrenees, Andalusia, the Spanish circum-Caribbean and back to the Iberian Peninsula are reconstructed through a longitudinal approach, revealing patterns that a focus on one woman or on movement between just two places would miss. Their physical movement is situated in the context of representations of relocation in the royal service as a burden and a sacrifice, before turning to an analysis of the networks and strategies constructed and obstructed by their mobility. Their movement was always intertwined with that of their male relations. Nonetheless, they played key roles in furthering their family’s political and economic interests, creating bonds that linked together distant parts of the Atlantic world, and articulating the Spanish empire.

Introduction

The digitalisation of archival sources and finding aids, the availability of search engines and machine-readable texts and the ease of accessing all these resources through the Internet allow historians to trace mobile lives in a way that would have been unthinkable a few decades ago. In the case of the early modern Spanish world, reconstructing the trajectories of itinerant royal officials is a relatively straightforward task. Letters patent, official correspondence, certified service records, and the documentation produced in support of requests for new appointments, promotions, and rewards in the field of honour enable us to trace their geographical movement and even provide insight into the ways in which they presented their experiences in order to garner further favour. However, these sources often obscure the role and presence of individuals who moved alongside royal officials, allowing us only passing glances at the trajectories and experiences of their wives, children, servants and enslaved people. Nonetheless, these individuals played key roles, simultaneously affecting and being affected by the mobility of the invariably male and white royal officials. Occasionally, however, we are lucky enough to be able to reconstruct the trajectories of some of these individuals, catching glances of their actions, character, relationships and perception by others, that allow us to infer certain aspects of their experiences of mobility.

This article reconstructs the highly mobile geographical trajectories of six women whose lives spanned the Spanish world in the transitional years between the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. They were all part of the same family and we are able to trace their movement thanks to the abundant documentation produced by their husbands, brothers and children who, collectively, proved extremely successful at converting royal service into increased social status.Footnote1 The documentation available offers little insight into how these women perceived themselves or their experience of staggered migration. Nonetheless, the traces we have are enough to begin to understand the multiple roles they played: furthering their family’s political and economic interests; seeking to advance, but sometimes obstructing, the careers of their menfolk; creating bonds that linked together distant parts of the Spanish world; and articulating an empire that was built by more than just men moving from one place to another in the service of the Spanish crown.

In trying to reconstruct the mobile experiences of María Juana de Knepper y Trippel (1666–1727) and her five daughters, this article draws on insights from both the “new mobilities paradigm,” particularly as interpreted by cultural geographers, such as Tim Cresswell,Footnote2 and new approaches to migration studies proposed by sociologists, such as Shanthi Robertson and Rosie Roberts.Footnote3 At the same time, it recognises that both the chronological distance separating us from the times of Knepper and her daughters, and the extent to which their gender obscured their presence in the archive, pose significant challenges to our enterprise.

Cresswell’s suggestion that “mobility can be thought of as an entanglement of movement, representation and practice” is a good starting point.Footnote4 The documentation available to us allows for the reconstruction in detail of the geographical trajectories drawn by the lives of our six subjects, “the fact of [their] physical movement.”Footnote5 However, we know less about the representations of movement that gave “shared meaning” to their experiences.Footnote6 We have hardly any surviving accounts produced by the women that could provide a frame of reference; women’s long-distance geographical movement, moreover, seems to have attracted little, if any, commentary at the time, and remains a significantly understudied subject amongst historians.Footnote7 Nonetheless, we are able to situate their mobility within the representations that englobed their father’s, brothers’, husbands’, and sons’ movement in the service of the Spanish crown. As we will see, these representations prioritised length of time spent in a place over distance travelled to reach it; they also tended to present long-distance relocation in the service of the crown as a sacrifice on the part of those moving, often involving significant expense, inconvenience, and risk to one’s health, family and property. Finally, although the complete absence of personal correspondence, memoirs, or any other kind of introspective documentation prevents us from directly accessing these women’s “experienced and embodied practice of movement,”Footnote8 this article argues that we are still able to catch occasional glimpses of what their experience was like. We can do this, particularly, by thinking about the power dynamics they were involved in because of their gender, age, marital status, class, and ethnicity, and because of the roles played by their menfolk in the governance of the Spanish world. In this sense, we can situate the mobility of these women, with their specific power relations, within the same “constellation of mobility” – that is, a set of “particular patterns of movement, representations of movement, and ways of practising movement that make sense together” – in which the lives of early modern Iberian itinerant royal officials operated.Footnote9

Cresswell’s emphasis in understanding movement, its representation and embodiment as intrinsically enmeshed in power dynamics, and his acknowledgement that these patterns are geographically and historically contingent and subject to change over time, are welcome correctives to some of the shortcomings that historians have found in the “new mobilities paradigm.”Footnote10 However, his approach is still too focused on movement itself and tries to cast too wide a net by purporting to be applicable to a range of instances of mobility “from the micro-movements of the body to the politics of global travel.”Footnote11 At the same time, like much of the work that falls under the umbrella of the “new mobilities paradigm,” it seems to be primarily preoccupied with understanding movement between point A and point B. As such, it offers relatively little in terms of furthering our understanding of “ongoing,” successive or staggered instances of long-distance movement over an individual’s life.

In this regards, recent migration studies’ use of longitudinal, biographical and narrative approaches to the study of “people’s mobile pathways and practices over their lives” offers a suitable complement.Footnote12 It allows us to understand mobility as an ongoing “complex matrix of interactions and connections over time and space, rather than a linear and permanent migration.”Footnote13 This perspective emphasises a broader understanding of the socially connected dimension of mobility. Thus, it is particularly concerned with “the extent to which mobility is determined by existing familial and social connections; [the] extent to which [it] creates ‘new’ networks of reciprocity and relationality; and how these relationships with both mobile and immobile ‘others’ shape ways of experiencing social and place attachment.”Footnote14 In some ways, this approach works better with the sources we have: genealogical documentation, judicial records and the occasional notarial document allow us, at least partially, to reconstruct the social connections of our subjects at different points (and places) in their lives. Thus, they offer glimpses of how these networks both affected and were affected by our subjects’ movement.

Moreover, recent migration studies’ emphasis on the non-linear, multidirectional and unpredictable nature of individuals’ movement over timeFootnote15 invites a more sophisticated understanding of mobility as a process that is ongoing or incomplete throughout an individual’s life. It is in this sense that I refer to the experiences of individuals whose lives were spent in multiple sites of empire, remaining for a few years in one place before moving on to another, as instances of staggered mobility.Footnote16 By doing so, I seek to highlight the often contingent nature of an individual’s presence in any one place, the frequently uncertain duration of each sojourn, and the unpredictability of the time, direction and motive of subsequent instances of long-distance relocation. I also aim to recognise that each instance of staggered migration built on previous experiences despite its taking place in different contexts and under different conditions. Thus, the driver for an individual’s movement may change from one instance of long-distance relocation to the next as the result of both unforeseen or unforeseeable accidents and the individual’s access to resources and choice. Simultaneously, this perspective allows us to recognise that the individual’s freedom to choose and availability of resources are not constant over time and that they do not always change in the same incremental or decreasing direction.

Adopting a longitudinal approach when considering female movement and mobility across the Atlantic world also allows us to explore a dimension of women’s experience which has received relatively limited attention from early modern Atlantic and global historians. Although nowadays women feature quite prominently in the historiography and the roles they played in building and maintaining empires, businesses, families, and knowledge are widely recognised, there is still a tendency to think of women as more static or less mobile than their male counterparts. We know much about the roles played by women who remained behind, on either side of the Atlantic, as their husbands and children travelled or relocated across the ocean,Footnote17 as well as about the commercial networks they built and the important roles they played in maintaining the bonds of empire.Footnote18 But we still tend to focus predominantly on women who remained in one place, even if acting as the articulating centre of communication networks, while their brothers or spouses moved from one place to the next;Footnote19 or our analysis of their mobility is frequently limited to single instances of movement, often between just two places or in a single direction, creating the impression that, when travelling overseas, women were overwhelmingly permanent settlers.Footnote20 With few exceptions, the historiography for the early modern period would seem to suggest that women did not lead “colonial lives” or experience movement through “imperial circuits” until the nineteenth century or outside of the British Empire.Footnote21

Of course, women moved across the Atlantic less frequently and in smaller numbers than men. Amelia Almorza Hidalgo estimates that, at the peak of Spanish emigration to Spanish America, between 1560 and 1630, women represented at best between 20 and 30 percent of Spaniards crossing the Atlantic.Footnote22 Similarly, for the first half of the eighteenth century, Isabelo Macías Domínguez calculated that, out of 8,203 Spaniards who travelled legally between Cadiz or Seville and Spanish America, only 623 were women, representing less than 8 percent of the total.Footnote23 Nonetheless, for this same period, women constituted the majority of relatives travelling alongside men who crossed the Atlantic to take up a royal appointment. The 1,596 imperial administrators, both civil and ecclesiastical, whose departure from Spain was registered by royal authorities took with them 307 female relatives – including wives, daughters, nieces, sisters, mothers and sisters-in-law – compared with only 206 male family members. Thus, women represented almost 15 percent of the individuals travelling to Spanish America in the royal service between 1701 and 1750.Footnote24

Still, the emphasis placed by studies of early modern migration on flows between one side of the Atlantic and the other has contributed to obscuring the often staggered nature of female mobility, both before and after the transatlantic journey. Unquestionably, throughout the early modern period, crossing the Atlantic was a major undertaking both financially and in terms of physical risk and discomfort. Similarly, the Spanish crown sought to control and regulate the transatlantic movement of people much more than it did movement between its different European or American territories.Footnote25 Yet, by focusing exclusively, or predominantly, on the transatlantic voyage we fail to place these experiences within the broader context of the mobile lives often led by individuals who ventured to cross the Ocean Sea. Although this is an issue that affects the way we have approached both male and female experiences of mobility in the early modern Atlantic, we know a lot more about the staggered migration of men than we do of women.Footnote26 Yet, experiences of female staggered mobility appear everywhere in the Atlantic world as soon as we start to keep an eye out for them.Footnote27

Thus, in the following pages I begin by offering a reconstruction of the geographical trajectories outlined by María Juana Knepper and her daughters’ lives. I then offer some reflections on the representation of the kind of staggered, long-distance relocation experienced by them, largely because of their menfolk’s careers as itinerant royal officials. A third section considers how they practiced and embodied movement. A final section considers the ways in which, through their successive relocations, these six women contributed to the development, transformation, creation and destruction of familial and social networks and relations. Overall, the article argues that adopting a longitudinal approach to these women’s lives allows us to reconstruct trajectories of “ongoing” or staggered mobility that would remain invisible if we focused exclusively on their movement between one place and another. Considering these six women’s lives collectively also allows us to see their movement in the context of shared instances or “constellations” of mobility as experienced by a broader group of men and women. Finally, I argue that while often obscured or overshadowed by the movement of the men in their lives, the staggered mobility of these six women was key to their family’s strategies and to the politics of the early Bourbon Spanish world.

Trajectories

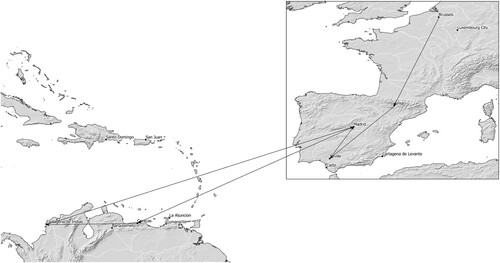

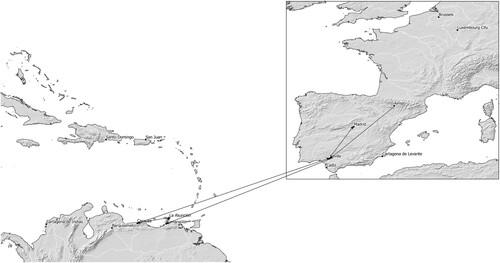

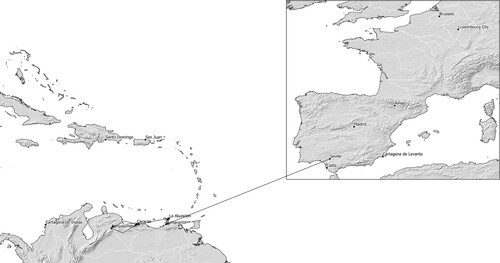

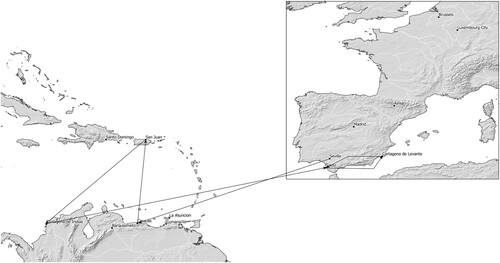

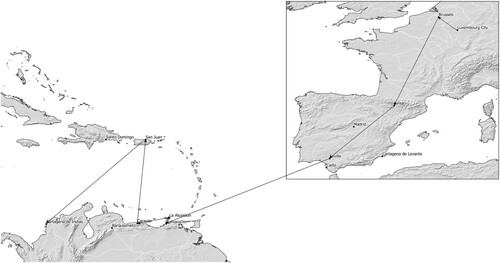

María Juana de Knepper y Trippel – see for a graphic representation of her life-trajectory – was born in Luxembourg City in 1666; it was also there that she married Alberto Bertodano, a Navarrese officer in the Spanish garrison of the city, in 1683.Footnote28 When Luxembourg was captured by the French the following year, Knepper and her husband relocated to Brussels, where their first daughter, Elena Juana Bertodano y Knepper (see ), was born.Footnote29 Because Alberto Bertodano had lost his right arm while resisting the French attack on Luxembourg, in 1687 he was allowed to travel to Spain to seek a new appointment more suitable to his physical limitations.Footnote30 Thus, the family left Spanish Flanders, relocating shortly afterwards to the Aragonese Pyrenees, where Bertodano served as the commander of a small fortress near the French border.Footnote31 The couple’s second daughter, Teresa Cecilia (see ), was born there, in Ainsa, in 1691.Footnote32 Three years later, they all relocated to Seville, after Bertodano was appointed commanding officer of the militias of Coria del Rio.Footnote33 The family lived in Seville until 1706, by then they had had four more children: Petronila Paula (see ), María Josefa (see ), Carlos Alberto and Josefa Escolástica (see ).Footnote34

Figure 1. Life-trajectory of María Juana Knepper y Trippel (Luxembourg City, 1666 - Cartagena de Indias, 1727).

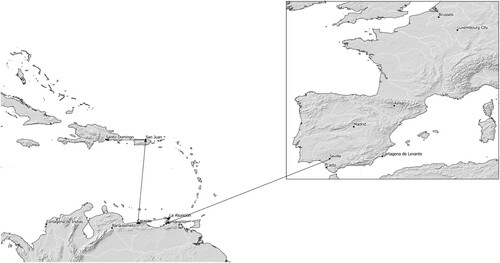

Figure 5. Life-trajectory of Petronila Paula Bertodano Knepper (Seville, ca. 1700 - Santo Domingo, ca. 1727).

Two years earlier, Bertodano had been appointed governor of Cumana in north-eastern South America.Footnote35 After several delays, the family relocated overseas in 1706 leaving their eldest and youngest daughters behind. By then, Elena Juana had married Jerónimo del Moral, a clerk in the central administration of the monarchy’s finances, and the couple had settled in Madrid.Footnote36 Josefa Escolástica, only months-old at the time, remained behind in Seville, presumably in a convent or in the care of friends of the family.Footnote37 The rest of the Betodano-Kneppers lived in Cumana until 1713. During that time, the couple’s last child to reach adulthood was born: a son named Andrés Jerónimo. Meanwhile, their second eldest daughter, Teresa Cecilia, married Cristóbal de la Riba Herrera, a resident of the Island of Margarita and relocated to La Asuncion, the island’s main settlement.Footnote38

At the end of his tenure in Cumana, the Council of Indies fined Bertodano an amount almost equivalent to one and a half years’ his pay as provincial governor.Footnote39 Faced with financial ruin and no prospects of further employment in the royal service, Bertodano travelled back to Spain, while María Juana and their children remained in La Asuncion with Teresa Cecilia and her husband.Footnote40 Bertodano’s journey to Spain rendered fruit and in late 1714 he sailed back across the Atlantic with a new letters patent – naming him interim governor of Caracas – and with Elena Juana, her husband and two daughters, and Josefa Escolástica in tow.Footnote41 Meanwhile, in Margarita, Cristóbal de la Riba had passed away, leaving Teresa Cecilia a widow with two infant daughters and complicating the situation for María Juana and the rest of her children.Footnote42

Early in 1715, and for about 18 months, the entire family reunited in Caracas. Shortly afterwards, Teresa Cecilia married for a second time.Footnote43 Her new husband was Antonio José Álvarez de Abreu, a Canarian jurist who had arrived from Spain on the same ship as Bertodano to oversee trade between the Iberian Peninsula and northern South America.Footnote44 A few months later, her sister María Josefa also married in Caracas.Footnote45 Although born in Spain, her husband, Juan de Vega Arredondo, was a long-time resident of northern South America with strong links to Caracas, Barquisimeto and Cumana.Footnote46 Towards the end of the summer of 1716, Bertodano, María Juana, their two youngest daughters and their two sons left Caracas for San Juan, Puerto Rico, where Bertodano would serve as interim governor until 1720.Footnote47 Elena Juana, Teresa Cecilia, and María Josefa remained behind in Caracas, where their husbands held important appointments in the fiscal and commercial administration of the province.Footnote48 While her parents were in Puerto Rico, the family’s fourth daughter, Petronila Paula, married Juan López de Morla, a former governor of the island and a well-connected merchant/soldier from Hispaniola. The couple settled in Santo Domingo.Footnote49

Bertodano’s last stint as Spanish American provincial governor took place in Cartagena de Indias, between 1720 and 1724. He travelled there from Puerto Rico in the company of his wife and their three youngest children.Footnote50 Shortly afterwards, their youngest daughter, Josefa Escolástica, married a Spanish naval officer, Segismundo Medrano, and set sail back for Spain; the marriage would not last long as Medrano passed away shortly afterwards.Footnote51 In Cadiz in 1723, Josefa Escolástica wed for a second time, to Alejo Gutiérrez de Rubalcava, an up-and-coming official in the administration of the Spanish navy.Footnote52 The couple initially settled in Cadiz.Footnote53 In the mid-1720s Petronila Paula and López de Morla passed away in Santo Domingo leaving behind a young orphaned daughter.Footnote54

Although Bertodano’s tenure in Cartagena de Indias ended in scandal – both he and María Juana were accused of engaging in illicit foreign trade –,Footnote55 the couple remained in the city for the rest of their lives. María Juana died there in February 1727.Footnote56 Barely a month after her passing, her eldest son, Carlos Alberto married a local woman and settled permanently in the New Granadan city;Footnote57 María Juana’s youngest child, Andrés Jerónimo, also married a Cartagenera, but relocated to Cadiz shortly afterwards.Footnote58 In 1729, Elena Juana and Jerónimo del Moral, left Caracas for Cartagena de Indias when he was promoted to an office in the region’s fiscal administration.Footnote59 Elena Juana’s reunion with her father and brother, however, was short-lived as del Moral’s office was suppressed only a few months after their arrival in the city. By the early 1730s, the eldest of the Bertodano-Kneppers, her husband and their nine children had all relocated back to Spain.Footnote60

Meanwhile, Teresa Cecilia and her children had also left Caracas around 1729 and returned to Spain. There, she reunited with her husband, who had left South America in November 1722.Footnote61 After spending some time in Madrid, he had settled in Cadiz in 1727, when he was appointed one of the judges of the Casa de la Contratación (the institution that oversaw trade between Spain and Spanish America).Footnote62 Once Teresa Cecilia arrived in the Iberian Peninsula, the family lived together in Seville for around a year.Footnote63 Finally, in 1731, they moved to Madrid, when Álvarez de Abreu was appointed to a seat in the Council of Indies.Footnote64 Roughly at the same time, Josefa Escolástica and Gutiérrez de Rubalcava relocated from Cadiz to Cartagena de Levante, in Murcia, when he was appointed chief administrator of Spain’s Mediterranean naval forces.Footnote65

Teresa Cecilia and Álvarez de Abreu settled permanently in Madrid, where she passed away in 1754, several years after her husband had been granted a title of nobility and had become the dean of the Council of Indies.Footnote66 Elena Juana and del Moral also settled in Madrid, where she passed away, already a widow, in the late 1750s.Footnote67 After nearly ten years in Cartagena de Levante, where she gave birth to at least six children, Josefa Escolástica and Gutiérrez de Rubalcava moved back to Cadiz, where he served as president of the Casa de la Contratación from 1742 until his death in 1747.Footnote68 Unfortunately, we do not know what happened to Josefa Escolástica after becoming a widow. For her part, María Josefa Bertodano y Knepper spent the rest of her life in Caracas, except for a brief sojourn in Barquisimeto.Footnote69 She was still living in the Venezuelan capital, as a widow, in 1741.Footnote70

Thus, and as through 6 and show, all six women travelled across the Atlantic at least once in their lives, and three eventually returned to Spain. As was frequently the case with Spanish women who emigrated to Spanish America, none of them crossed the ocean more than once in each direction.Footnote71 Between them, these six women lived in at least 14 different towns and cities spanning the Spanish world, from Flanders to New Granada. After the family left Seville in 1706, and except for a period of about 18 months in Caracas, the six women were never again in the same place at the same time. By the same token, however, there was almost always a place where at least two of them were living simultaneously, even after all the daughters had left the parental home. The pairings, however, changed over time, suggesting that family bonds, rather than affinity between specific individuals was probably what drove them.

Table 1. Places of residence of María Juana Knepper y Trippel and her daughters.

Of all six women, María Josefa led the least mobile life, living in only five different places and spending over half her life in Caracas. María Juana, the mother, was the most mobile: relocating at least nine times throughout her life and never settling twice in the same place. Elena Juana, Teresa Cecilia and Josefa Escolástica – the three that crossed the Atlantic in both directions – also experienced frequent instances of staggered migration, each resettling at least seven times but, unlike their mother, they all lived twice in at least one city. Even Petronila Paula, despite her short life, at the time of her death had lived in six different locations.

Although their relocations were almost invariably driven by the careers and fortunes of their father and husbands, all six women spent at least a few months of their lives, and in some cases several years, living apart from their immediate menfolk. Josefa Escolástica spent the first five years of her life apart from her parents, as she was left behind in Seville while they went to Cumana. She spent some time on her own again, probably in Cadiz, after the death of her first husband and before her second marriage. Similarly, after Cristóbal de la Riba Herrera passed away, María Juana, Teresa Cecilia, María Josefa and Petronila Paula all lived on their own – with Knepper’s two sons who were still children – in La Asuncion, Margarita, for about a year, while Bertodano was in Spain seeking appointment to Caracas. María Josefa would then spend some time in Caracas without her husband, while Vega Arredondo was taking the residencia of her father’s successor in the governorship of Cumana.Footnote72 Elena Juana, also spent some time in Caracas without her husband around 1720, while Jerónimo del Moral travelled to Spain in search of an appointment in the city’s fiscal administration.Footnote73 Finally, Teresa Cecilia remained in Caracas for close to seven years after her second husband returned to Spain in 1722. In these last three cases, however, the women were always in the company of two of their sisters and their husbands. In this regard, the experience of the Bertodano-Knepper’s was not atypical. Across the early modern Spanish world, married women often spent significant amount of time apart from their husbands, managing the affairs of their households and families.Footnote74 Households led by women, either widowed, married or single, often comprised large part of the population of many towns and cities in the Spanish Atlantic and beyond.Footnote75

Although separated by nearly 300 years, the lives of the Bertodano-Knepper women followed complex trajectories, marked by ongoing movement similar to those of the contemporary migrants studied by Roberts and Robertson et al.Footnote76 Their relocations, although usually linked to key events in their menfolk’s lives and careers, were often marked by serendipity or misfortune rather than by deliberate choice. Often at the unpredictable mercy of royal favour and the complex central bureaucracy of the Spanish Monarchy, it is difficult to see their trajectories as primarily the product of a calculated plan or strategy. Nonetheless, the trajectories of the six women reflect a pattern of successive settlements of unpredictable duration that was common amongst those connected to the middling sectors of the Spanish imperial administration but which historians are only now starting to analyse systematically.

Representations

The trajectories outlined in the previous section constitute but one of three entangled aspects of mobility: the “fact of physical movement.” However, simply reconstructing the paths followed by our subjects throughout their lives “says next to nothing about what these mobilities are made to mean or how they are practiced.”Footnote77 Thus, the second of the three entangled aspects of mobility are the “representations of movement that give it shared meaning.”Footnote78 As mentioned before, we have no letters penned by any of the six Bertodano-Knepper women that explicitly addresses their ongoing movement or the meaning they attributed it. The closest we come to this are a handful of notarial records and petitions that acknowledge and document their and their menfolk’s physical movement.

Amongst the latter is a petition submitted to the Council of Indies on behalf of Teresa Cecilia Bertodano Knepper requesting a pension for herself and her two infant daughters after the passing of her first husband. The claim rests on the services of Teresa Cecilia’s father and her late husband, as well as on the former’s inability to support her and her daughters because of his own numerous family members and debts incurred in the royal service.Footnote79 In support of her case, Teresa Cecilia provided Cristóbal de la Riba’s certified service record, a copy of her father’s letters patent as governor of Caracas, and the statements of three witnesses who had known her husband and were familiar with her situation as a widow.Footnote80

As other similar documents do, Teresa Cecilia’s file provides us with some idea of how relocation in the royal service was represented at the time. The summary of the file, produced by a clerk in the office of the secretary of the Council of the Indies, offers further detail regarding how the crown perceived physical movement in the careers of its officials. Although the focal point of service records tends to be the length of service, often counting down to a day the time an officer held a certain rank or the length of an official’s posting in a particular place, they also carefully record the locations where services were provided. In the case of soldiers, this normally means identifying the region where their unit was stationed, any fortresses they garrisoned, battles they fought in, and the location where any other meritorious actions took place.Footnote81 In the case of government officials, it usually comes down to the province in which they served or the city in which they were based. Travel from a provincial capital to the interior of the province is normally only mentioned when the official’s presence in the place was noteworthy because his predecessors had not normally visited, because it resulted in an extraordinary service to the crown, because it involved taking an uncommon risk, or because it threatened the individual’s health or property.Footnote82

Officials themselves normally presented their travel as a sacrifice made out of loyalty and obligation to the crown. They stressed misfortunes experienced while travelling,Footnote83 the costs involved in relocating, especially if they had large families,Footnote84 and the negative impact of their destinations’ climate on their and their loved ones’ health.Footnote85 Although some officers explicitly asked to be allowed to return home,Footnote86 most asked to be sent elsewhere, often suggesting a few desired destinations, thus indicating their willingness to continue to risk their lives and fortunes in the service of the monarchy.Footnote87 Therefore, staggered migration is presented as a burden, undertaken out of fealty, often at great personal risk and expense.

In this regard, the arguments presented in support of Teresa Cecilia’s request for a pension, and the interpretation of them provided by the Council’s clerk, are typical. The summary of the services rendered to the king by Cristóbal de la Riba Herrera stresses how he frequently “passed” from his home island of Margarita to other locales: to the island of Trinidad to fend off French ships; to serve in the garrison of the fortress of Saint Francis in St Thomas of Guyana; to deliver official correspondence to the governor of Cumana; or to transport royal monies from Caracas. The account also stressed the sacrifices made by Riba Herrera, “risking his life and losing a ship of his own.”Footnote88 Similarly, summarising Bertodano’s services, the Council’s clerk stressed the 27 years spent in the army in Flanders and Spain, participating in multiple operations and “losing an arm in one of them,” before being appointed to Cumana and then to Caracas. Furthermore, the clerk commented on the debts incurred by Bertodano in paying for his voyage from Cadiz to Caracas, which rendered him unable to succour his widowed daughter.Footnote89 Finally, the summary’s only reference to Teresa Cecilia’s own mobility, stresses how Riba Herrera’s death had left the young widow and her daughters “in such poverty that they were forced to pass [from the island of Margarita] to the province of Caracas.”Footnote90

These same themes are present in the only document contained within the file penned by Teresa Cecilia herself. On 5 September 1715, the young widow petitioned the Marqués de Mijares, alcalde ordinario (first instance magistrate) and deputy captain general of Caracas, to take and certify statements from three witnesses who could speak to her situation. The witnesses were to answer a series of questions submitted by Teresa Cecilia. The first two questions were meant to establish her identity and relationship with her parents, late husband, and daughters. The third and fourth questions aimed to demonstrate that “poverty” and “exposure” (desabrigo) had been the reasons why she had left La Asuncion and joined her parents in Caracas. In both the latter questions, Teresa Cecilia clearly stated that, for her, La Asuncion was a “foreign land” (tierra extraña), as was Caracas for her parents, implying that their very presence there made them vulnerable, as it cut them off from the support networks they would have otherwise been able to rely on. The fifth and last question aimed to establish that her father was in Caracas only because of the appointment he held. It clearly indicated that serving as interim governor of Caracas was both a reward for his merits and long years of service as well as a burden willingly undertaken out of loyalty to the king. In fact, Teresa Cecilia implied that service overseas was a sacrifice, similar to her father’s loss of a limb in the battlefields of Flanders. After all, the trip from Spain to Caracas had landed him in significant debt, making it impossible for him to support her and her young daughters on top of his own “large family of wife and children, most of whom are still infants.”Footnote91

Thus, the multiple, long-distance relocations of the six women analysed here should be placed in this context. Although the women themselves did not move in the service of the king, their mobility was included in the sacrifices made by their menfolk out of loyalty to the crown. Like the men they travelled with, they emphasised the risk to their life and health and, because of their gender, they were perceived as being particularly at risk of falling into poverty and destitution. The movement of itinerant royal officials and their families was coded as a necessary encumbrance undertaken by the individuals affected for the benefit of the monarch and the realm.

This representation of long-distance movement as a burden, as something individuals undertook only out of great necessity or obligation, contrasts with the assumption underlying much of the work done under the “new mobilities paradigm”: that mobility is fundamentally desirable. Thus, for instance, Cresswell’s claim that “mobility is a resource that is differentially accessed,” while essentially fair, rests on the explicit assumption that “[w]e are always trying to get somewhere. No one wants to be stuck or bogged down.”Footnote92 The notion that immobility is never a choice, but rather the result of lack of freedom or resources, is problematic. While it makes sense when talking about micro-mobilities –movement of the body or even movement within a town or village –, the assumption that every individual has a desire to move long-distance is perhaps too rooted in contemporary western culture.

However, by the same token, the coding of long-distance mobility as a burden, a sacrifice made out of loyalty or forced by misfortune, may be partly responsible for obscuring female instances of staggered mobility in the early modern Atlantic world. In the summary presented to the Council of Indies, the description of Teresa Cecilia’s relocation from Margarita to Caracas as forced upon her by the state of destitution entirely omits the fact that this was her fourth instance of long-distance relocation. This is significant as the clerk writing the summary was well aware of at least her last two resettlements. The witness statements Teresa Cecilia submitted to the Council alongside her petition made it clear that she had arrived in Cumana with her father and that she had moved to Margarita only after her marriage to Riba Herrera.Footnote93 Yet, if one read the clerk’s summary alone, one could only guess that Teresa Cecilia was not a native of Margarita because of the references to her father’s career in Spain.

A similar situation is evident, in relation to Elena Juana Bertodano Knepper, in a letter from the Audiencia (high court) of Santo Domingo to the king dated 17 August 1719. The explicit aim of the letter was to complain about Jerónimo del Moral’s travels through the Caribbean, seemingly without having undergone a residencia (end of tenure judicial enquiry) for the time he served as interim accountant of the royal exchequer in Caracas. When del Moral arrived in Santo Domingo “from Cumana, having called at the island of Puerto Rico,” the Audiencia noted that “this individual had been wandering from port to port, without legal justification for it, particularly while his wife and children remain in the city of Caracas.”Footnote94 The Audiencia’s negative interpretation of del Moral’s mobility contrasts sharply with the argument made by the governor of Santo Domingo – and by del Moral himself – in explaining why he travelled from Caracas to Madrid in 1719.Footnote95 This suggests that just as those “forced” to move in the royal service saw long-distance mobility as a sacrifice, royal authorities often saw the mobility of those who were not explicitly moving for the benefit of the king or the realm as undesirable.Footnote96

But more significant for our purposes here is the Audiencia’s reference to Elena Juana and her children as remaining in Caracas while del Moral “wandered” through the Caribbean. The letter is ambiguous as to whether Caracas was Elena Juana’s and del Moral’s place of origin: it makes no reference to the family crossing the Atlantic in 1714 and its description of del Moral’s activities in the Venezuelan capital also fails to indicate with any clarity whether he had travelled there before his appointment or not.Footnote97 However, by pointing out that del Moral was traveling without his wife and children, the Audiencia made reference to Spanish legislation discouraging married men from leaving their wives and children behind, particularly when travelling from Spain to Spanish America.Footnote98 This preoccupation with women left behind was manifest in the witness-statements individuals seeking a licence to travel from Cadiz or Seville to Spanish America were required to provide at the Casa de la Contratación.Footnote99 The same concern lay behind the crown’s insistence that provincial governors should make married men living in their jurisdictions without their wives return to their homes.Footnote100 Implicit in these concerns is an assumption that women stayed behind while men travelled and relocated, which may well reflect an element of social practice,Footnote101 but which also helped obscure the experiences of women like the Bertodano-Kneppers, who relocated repeatedly throughout their lives in and outside the company of men.

Embodied practices

Having dealt with both “the fact of physical movement [… and] the representations […] that give it shared meaning,” we now turn to the third entangled aspect of mobility: “the experienced and embodied practice of movement.”Footnote102 The specific ways in which individuals practice and embody mobility are ultimately determined by the power structures within which they exist, that is to say, they are eminently political and experienced differently based on gender, ethnicity, age, class, etc.Footnote103 Although the sources we have often provide little information and detail about each individual instance of mobility, this section offers some reflections on how the gender, age, marital status, ethnicity and class of the Bertodano-Knepper women affected their movement, which become visible when considering their experiences jointly and longitudinally.

When it comes to understanding how individuals experience movement, the “new mobilities paradigm” has often stressed the difference between “being compelled to move and choosing to move.”Footnote104 In this regard, it would be easy to think that María Juana and her daughters relocated repeatedly, particularly while the latter were young, led by the direction in which Bertodano’s career moved, having no say on when and where they moved. Later on in their lives, instances such as the description of Teresa Cecilia’s relocation from Margarita to Caracas as forced on her by her poverty, would still suggest they had little say in their movement. However, we should remember that representations like those discussed in the previous section often constitute arguments crafted to curry favour with the crown, rather than factual descriptions of cause and motivation.

Thus, it would be inaccurate to assume that the women we are studying were always compelled to move while their menfolk more often chose to do so. This, in many ways, is a false dichotomy and needs to be analysed in more detail. It is easy to assume that men always made the choice to seek or accept an appointment that would see them and their family move homes. However, it is also possible that a decision to move, or not, was made jointly by a couple or a family group.Footnote105 María Juana Knepper y Trippel’s last will and testament, written in Cartagena de Indias shortly before her death in 1727, states that since the earliest days of their marriage it had been her who managed Bertodano’s wages, and that she had done the same for her sons.Footnote106

The practice, at least as far as a wife handling her husband’s income goes, was not uncommon in the early modern Spanish world, particularly in the case of husbands who were frequently, or for prolonged periods, away from the family home.Footnote107 Thus, it is possible that María Juana began managing Bertodano’s income while he was a prisoner of the French following the siege of Luxembourg.Footnote108 For whatever reason, they seem to have continued the practice after they left Flanders, even though during their time in Ainsa Bertodano did not see frequent military action or spend much time away from the fortress of San Bartolome. After the family relocated to Seville, from where Bertodano frequently travelled the relatively short distance to Coria del Rio and where he once again participated in military operations during the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1713), leaving María Juana to manage the family’s resources would again have made sense.Footnote109 Thus, if for over two decades she had managed the family’s finances, it seems reasonable to think that she may have also been involved in other key decisions affecting their future, such as Bertodano’s requesting an appointment to the Indies in 1704 after the crown abolished his post as commander of the militias of Coria.Footnote110

María Juana, moreover, was not the only one of the six women whom we know played a significant role in managing the affairs of their respective nuclear families. As discussed earlier, we know that Teresa Cecilia had petitioned the crown for financial support for herself and her young daughters after her first husband died and that she had personally initiated at least some of the bureaucratic procedures. While her petition at the time was fruitless, fourteen years later, in 1729, she received from the Crown an annual grant to be drawn for the rest of her life from the funds of the Casa de la Contratación. The stated purpose of the annuity was to help support her large family and to complement the “small salary” her husband earned as one of the Casa’s judges.Footnote111 The grant, secured around the time of her return to Spain from Caracas, may have influenced her decision to migrate, and in all likelihood played an important role in allowing the family to settle down in Madrid shortly afterwards. More significantly, because the grant was made explicitly to her, it increased her personal assets and ensured that, should she become a widow again, she would be able to support her children regardless of whether she was living in a tierra extraña or not. Similarly, there is reason to believe Elena Juana had a say in her family’s affairs throughout her marriage to Jerónimo del Moral. After all, in July 1753, her husband – who was bedridden and unable to write – granted her a power of attorney authorising her to write his final will and testament for him. Elena Juana did so on 30 October 1753, shortly after del Moral’s passing.Footnote112 Thus, as in the case of their mother, it seems likely that women who were actively involved in managing their families’ affairs would also have had a say in decisions to relocate long-distance.

Similarly, we should not forget that, as recent migration studies have stressed, staggered migrants’ pathways are often contingent or serendipitous, or the individuals who experience ongoing mobility perceive them as such.Footnote113 The movement of itinerant royal officials in the early modern period was frequently propelled by unforeseeable circumstances; accidents and the often unpredictable course of the Spanish bureaucracy meant that even the officials themselves were restricted in the choices they had regarding when and where they moved. There is no doubt, for example, that Bertodano’s decision to travel back to Spain in 1713 to deal with the fine imposed on him by the Council of Indies and to seek a new appointment was not part of his – or his and his wife’s – original plans. Instead, Bertodano had to undertake the expensive and risky trip to revive his career and the family’s finances.Footnote114 The decision that María Juana and her children would remain behind in Margarita with Teresa Cecilia and her husband may have been forced on the family by financial constrains or may actually reflect a longer-term strategy, as discussed further in the next section.

Similarly, Jerónimo del Moral and Elena Juana’s decision to return to Spain from Cartagena de Indias in 1730 was also not a choice planned by either; instead, it was forced upon them by the Crown’s decision to suppress del Moral’s office.Footnote115 The fact that del Moral sought further appointments to American offices at least twice upon the family’s return to Spain, suggests that their plan had not been to settle back permanently in Madrid.Footnote116 Thus, one might ask why they decided for the whole family to leave Cartagena de Indias together in 1730 when, ten years earlier, Elena Juana and their children had stayed behind in Caracas while del Moral travelled to Spain to seek a new office. Could it be that Elena Juana’s experience of that instance of immobility in Caracas made her unwilling to stay behind again in 1730? Thus, it would seem that gender alone did not deny women choice within an established marriage, but rather that decisions to relocate were often forced on the family unit by unexpected events, or taken jointly, drawing on previous experiences and expectations.

By contrast, there is little doubt that age, particularly in relation to legal minority which extended until a child’s marriage or their 25th birthday,Footnote117 significantly constrained their say on whether to move or not. It is significant that with only one exception, all of María Juana’s children, as long as they remained single and under the age of 25, moved only and always when their parents relocated. The one exception, as we saw before, was Josefa Escolástica who, only months old at the time, was left behind in Seville while her parents and siblings sailed for Cumana in 1706. In most cases, however, it was marriage that led the Bertodano-Knepper children to migrate independently from their parents for the first time. It is unclear, however, how much say they would have had, particularly the daughters, either in the marriage itself or in their subsequent relocation. Thus, Elena Juana’s marriage to Jerónimo del Moral in 1705 led to her relocation from Seville to Madrid, although this could almost be read as an instance of immobility considering her parents and siblings simultaneous moved across the Atlantic. The timing of the marriage, about a year after Bertodano had secured his appointment to Cumana and while he was making arrangements for leaving Seville, suggests the union may have been arranged as a strategy to ensure the family retained links to Spain and, particularly, to the court in Madrid.Footnote118

Similarly, Teresa Cecilia’s first marriage involved relocation from Cumana to La Asuncion; Petronila Paula’s marriage saw her move from San Juan to Santo Domingo; and Josefa Escolástica’s first marriage involved her leaving Cartagena de Indias for Cadiz. Moreover, in all three cases resettlement followed seemingly sudden marriages to men that were essentially strangers and who were significantly older than their brides. Cristóbal de la Riba Herrera and Juan López de Morla were much closer in age to Bertodano than they were to Teresa Cecilia and Petronila Paula respectively, and in neither case is there evidence to suggest the men had been close acquaintances or friends of the family before their weddings.Footnote119 We do not know what the age difference between Josefa Escolástica and Segismundo Medrano might have been, but by all indications, their marriage also took place without much previous interaction and involved, perhaps, the most drastic instance of relocation far from the parental home of any of the Bertodano-Knepper children.Footnote120

Although canon law required the consent of both parties before a marriage took place and marriages in early modern Hispanic society were normally negotiated, taking into account the child’s prefernces,Footnote121 it seems likely that in these cases, the young brides would have accepted, rather than chosen, their nuptials and subsequent relocations. These circumstances contrast significantly with those under which some of the other marriages of the six women took place. In the case of the parents, for instance, Bertodano had been in Luxemburg City for about a year before his marriage to María Juana, so it is at least possible that the couple had met and courted before their weeding took place;Footnote122 moreover, the age difference between the two was barely six years and they did not leave Luxemburg until the city fell and Bertodano was taken prisoner a year later.Footnote123 Teresa Cecilia and her second husband, Álvarez de Abreu, were also close in age, had known each other for a little over a year before their wedding, and after the marriage they continued to live in the same city as her parents and sisters.Footnote124 Additionally, as a widow, Teresa Cecilia would have had much more of a say as to whether to remarry or not and, according to Álvarez de Abreu, the marriage had been agreed between him and his bride-to-be without her father being involved at all.Footnote125

The death of a husband could also constitute a sudden, unexpected driver for mobility. However, the decision to actually move – as when a recently-widowed Teresa Cecilia relocated from Margarita to Caracas in 1715 –, or not to do so – as when Josefa Escolástica’s first husband died and she stayed in Cadiz and eventually married for a second time – could, to an extent, be a fully “free” choice or one compelled by economic necessity, depending, amongst other things, on the financial situation the widow was left in and the support networks she could access. Although widows enjoyed certain protections under Spanish law, women living on their own, especially if they had children, were very much at risk of falling into poverty.Footnote126 It is in this light that we should interpret Teresa Cecilia’s decision in 1715 to leave Cumana with her mother and siblings and – at her father’s request – re-join the parental home in Caracas.Footnote127

Thus, the reasons why these women relocated, and the say they had in their movement, varied. They were influenced by their gender, age, and family relations, but their reasons to move were more complex than simply being forced to do so alongside men who chose to. In this context, we might understand “compelled,” as opposed to chosen, movement or immobility as not simply determined by power relations and financial considerations, but also by affective connections or perceived obligations. More significantly, perhaps, we should think free and compelled movement as the extremes of a continuum, rather than as two only options when analysing an individual’s reasons to move.

At the same time, gender, class, and ethnicity influenced directly how the six Bertodano-Knepper women moved across the Spanish Atlantic world. As was often the case for Spanish women,Footnote128 the six of them first crossed the Atlantic as part of a family group led by their father. Moreover, in all instances in which we know exactly when and how they travelled, not just when crossing the Atlantic, they did so in the company of a male relative or a male agent appointed for that purpose. Thus, when María Juana, Teresa Cecilia and their children travelled from La Asuncion to Caracas, they did so in the company of Vega Arredondo, whom Bertodano had despatched specifically for the purpose of escorting his family to join him.Footnote129 Similarly, Elena Juana – and her two young daughters – travelled from Spain to Caracas in the company of both her father and husband. The latter accompanied her and her children from Caracas to Cartagena de Indias and from there back to Spain. Josefa Escolastica, who had remained in Seville when the family first travelled to Cumana, only crossed the Atlantic when her father returned to Spain; she then travelled in his company from Caracas to Puerto Rico and from there to Cartagena de Indias, before travelling with her first husband, Segismundo Medrano, from the New Granadan port to Cadiz. The one apparent exception would be Teresa Cecilia’s return journey from Caracas to Spain around 1729. However, the dates allow for her voyage to have coincided with her younger brother and his first wife’s relocation from Cartagena de Indias to Cadiz. In this regard, their experience – no doubt a result of the perceived vulnerability of women at sea – contrasts significantly with the experience of male members of the family who often travelled on their own, both within Spanish America and across the Atlantic.

Their gender and class also help explain why, as far as we can tell, no Spanish authority sought to prevent or challenge their movement at any point. On departing from Spain, the fact that they were the family of newly appointed provincial governor and a high-ranking military officer was enough for them to be allowed to travel without having to provide evidence of their marital status or their pure Christian ancestry, as servants and would-be-migrants from lower social classes were invariably required to do.Footnote130 Servants constituted the single largest category of people legally emigrating from Spain to Spanish America in the early eighteenth century,Footnote131 thus providing evidence of one’s eligibility to embark across the Atlantic would have been an element of the average transatlantic migrant’s experience that the Bertodano-Kneppers were exempt from on account of their father’s status and calidad. While the cost of providing these informaciones seems to have been relatively accessible,Footnote132 the need to provide them constituted an additional burden on would-be-travellers and could, on occasion, result in a person being denied a licence.Footnote133

The Bertodano-Knepper’s wealth and status would also have eased the family’s movement at other points in their staggered mobility. During the navigation between Spain and South America, given Bertodano’s position as a provincial governor, the whole family would have undoubtedly travelled in a cabin and eaten their meals at the captain’s table, rather than sleeping on deck and eating with the crew.Footnote134 Similarly, when Jerónimo del Moral received his promotion from Caracas to Cartagena de Indias, he was in a position to lease a ship to transport his wife and nine children to their next posting.Footnote135 While the trip would not have been easy, as the winds and currents made the voyage East from Caracas particularly slow and difficult, it would still have been much easier to undertake by sea than by land, particularly including several young children. As del Moral himself admitted, leasing a ship also meant the family did not have to wait until someone else decided to sail between both ports. Thus, their social status, derived in part from their menfolk’s role in the Spanish imperial administration and from the financial resources the family could draw on, played an important role in removing obstacles and facilitating their movement compared to those of other Spaniards.

The experiences of mobility of the Bertodano-Kneppers were also marked by their ethnicity. The majority of women crossing the Atlantic in the early eighteenth century would have done so in bondage. Enslaved African women, although fewer in number than enslaved men, significantly outnumbered European women arriving in the Americas.Footnote136 The conditions of travel experienced by the Bertodano-Kneppers would have been incomparably better than the gruesome middle passage experienced by enslaved men and women from Africa.Footnote137 For the latter, even movement as part of a Spanish household would have been significantly different as a result of their ethnicity and legal status.

We know, for example, that over the years the Bertodano-Kneppers owned a number of enslaved Africans who were forced to move, or not, at different points in time regardless of what they, and sometimes even what their enslavers, would have preferred to do. For example, while in Caracas, Bertodano’s household included eight enslaved individuals.Footnote138 Four of them were adults: Antonio and María were a married couple; Francisco had been born in Africa; and Esteban had died before August 1716. A further four were young children: Jerónimo, aged four, had had a twin brother who died in the spring of 1716; Pedro José was five or six; and Elena was seven.Footnote139 Except for Francisco’s, their place of origin is unknown, but considering the Bertodano-Kneppers had only been in Caracas for some eighteen months it would not be surprising if their enslaved servants had been purchased in Cumana or Margarita and had arrived in the Venezuelan capital from La Asuncion with the rest of the household. None of them, however, travelled with their enslavers to Puerto Rico as the six who were still alive in the late summer of 1716 were seized, with the rest of Bertodano’s property, as part of the investigation into the role he played in obstructing the trade of the Honduras Company.Footnote140 Thus, enslaved men and women’s status as chattel could clearly determine or restrict their movement beyond their own and even their enslaver’s will. Their experience contrasts significantly with the ways in which the Bertodano-Knepper women were able to move across the Spanish Atlantic because of their white and free status.

Finally, without personal correspondence or memoires, it is practically impossible to know how these women “felt” about their mobility or what emotions it generated.Footnote141 There are instances, however, in which we can make educated inferences. For instance, it would not be difficult to imagine the shock eight-years-old Josefa Escolástica must have felt in 1714 when her father, by then an old man in his fifties, whom she had never met before, suddenly showed up in Seville and told her he was taking her across the Atlantic to live in Caracas. Of course, whether the shock led to excitement and hope or anxiety and pain is impossible to know. Similarly, it seems plausible that for Teresa Cecilia, relocating from Seville to Madrid in 1731 was a bittersweet experience. Upon their arrival in Spain from Caracas around 1729, Teresa Cecilia’s two daughters from her first marriage, Jerónima and Manuela de la Riba Herrera, had professed as nuns in a Cistercian convent in Seville (and in doing so renounced their share of their mother’s inheritance).Footnote142

Given its timing, the decision may be interpreted as a move to consolidate resources and settle both young women, who were by then in their late teens, at a point in time when their stepfather’s finances might not have been best suited to find them appropriate husbands in Spain.Footnote143 But it also meant both of them stayed behind when their mother, stepfather and stepsiblings relocated to Madrid. Eight years later, however, both sisters transferred from Seville to a convent in Madrid. Álvarez de Abreu justified the request for his stepdaughters’ relocation on the grounds that the climate in Seville was detrimental to their health. However, it is possible that the decision to have them move – which must have been significantly expensive as it required, amongst other things, a papal dispensation –, was driven by their mother’s desire to be closer to them once settled at court and when the family’s fortunes were on better footing.Footnote144

Thus, the paucity of documentation available puts certain limits on our ability to access the embodied practice of these women’s mobility. By looking at their experiences collectively and longitudinally, however, we are able to gain some insight as to how their gender, age, marital status, class and ethnicity affected their ability to choose whether to move or not, the obstacles they encountered when moving, and the emotions that movement might have generated.

Family strategies and imperial governance

Adopting a collective and longitudinal perspective also allows us to gain a better understanding of the socially connected dimension of these women’s mobility, of how it contributed to family strategies, to the careers of their menfolk and to the development of networks that articulated the early modern Spanish world. When looking together at the movement of these six women over time, we are able to see how their mobility was simultaneously “determined by existing familial and social connections,” and the catalyst for the creation of “‘new’ networks of reciprocity and relationality.”Footnote145 Three examples illustrate this particularly well: the cross-Caribbean network created through the marriages and relocations of all five of María Juana’s daughters; the role attributed to María Juana herself in illicit trade in Puerto Rico and Cartagena de Indias, and the impact it had on Bertodano’s career; and the role played by Elena Juana, Teresa Cecilia, and María Josefa in hiding their father’s assets from being seized in Caracas in 1716, thus protecting the family’s interests.

Looked at together, the marriages of the Bertodano-Knepper sisters celebrated while their father served in the Caribbean seem to suggest a family strategy articulated around the creation of a well-anchored, commercial, and political network. Teresa Cecilia’s marriage to Cristóbal de la Riba Herrera, while her father was governor of Cumana, gave the family access to ships operating out of the island of Margarita, an almost unavoidable calling port on the way in and out of Cumana and the gulf of Araya.Footnote146 Moreover, Riba Herrera was a close associate of the incumbent governor of Margarita and probably still had links to Trinidad and Guyana, where he had served and traded in the past.Footnote147 Similarly, María Josefa’s marriage to Vega Arredondo created strong links with various parts of the province of Venezuela, particularly Caracas, Cumana and Barquisimeto, where he had well-established personal and patronage connections.Footnote148

Petronila Paula’s marriage to López de Morla extended the family’s reach from Caracas and Puerto Rico to Santo Domingo, where he retained strong political and social bonds. The marriage also granted them access to a small flotilla of ships capable of navigating between the Antilles, which López de Morla had often used for trading and privateering, and ensured that, after Bertodano’s tenure in San Juan came to an end, the family still retained good links to the islands.Footnote149 By providing access to vessels capable of sailing across the Atlantic, and a direct link to Cadiz, Josefa Escolástica’s marriage to Segismundo Medrano would have been the capstone of a family network that, at that point in time, connected at least Caracas, Santo Domingo and Cartagena de Indias.Footnote150

It can be no accident that the profiles and careers of Riba Herrera, Vega Arredondo and López de Morla bore strong similarities to each other: they had all served in various parts of the Spanish circum-Caribbean, had travelled frequently while on the royal service, while in all likelihood engaging in commercial activities alongside their official business. Moreover, whether born in the Americas or in Spain, all three men had well established links with more than one province in the region. Medrano seems to be a little different, in that he was a naval officer based in Cadiz, but his involvement with the Carrera de Indias – sanctioned trade between Spain and Spanish America – would have nonetheless provided good opportunities for carrying out commercial activities on the side; and while he did not own any vessels that we know of, his command of royal ships, particularly avisos – ships sailing on their own and transporting correspondence –, was probably even more valuable.

We know that, at least occasionally, Bertodano had engaged in cacao trade across the Caribbean since his tenure in Cumana, and it is likely that the network built through his daughters’ marriages and relocations allowed for trade on a greater scale.Footnote151 Equally significantly, we know the network was used for political purposes and that the connections built could be used to facilitate travel and help advance the careers of its members. The letter from the Audiencia of Santo Domingo to the king cited earlier, in which the justices complained about Jerónimo del Moral’s “wanderings” through the Caribbean, offers us a glimpse of how the network created by the Bertodano-Kneppers worked. We know del Moral’s voyage from Caracas to Spain resulted in his appointment as treasurer of the Royal Exchequer in the Venezuelan province. The Audiencia’s complaint, however, sheds light on his itinerary and on the political levers he was able to pull to aid his purpose. Del Moral left Caracas shortly after Vega Arredondo had returned from Cumana and taken back the office of accountant of the Royal Exchequer, which his brother-in-law had served in his absence.Footnote152 At that same time, Álvarez de Abreu’s influence in the province was rising through his collaboration with the viceroy of New Granada.Footnote153

The Audiencia’s letter, however, shows del Moral’s first calling port upon leaving Caracas was Cumana, which represented a detour if his destination was the Iberian Peninsula, but made sense from a commercial and in some ways a political perspective. As a province, Cumana was entirely independent of Caracas, although trade and fiscal concerns had created strong bonds between both territories. Since the creation of the viceroyalty of New Granada, Cumana had become politically subordinate to Santa Fe, instead of Santo Domingo, and its ties to Caracas had strengthened as much of the communication from the viceregal capital went through the latter city. There was, moreover, a strong link between the family and Cumana, not only because of the time Bertodano had served as its provincial governor, but because of the interests that Vega Arredondo retained in the city, which could have only been strengthened during his recent sojourn to take the residencia of Bertodano’s successor.Footnote154

From Cumana, del Moral sailed for Puerto Rico, where Bertodano was still serving as provincial governor. Maritime connections between Cumana and Puerto Rico were not infrequent and they often involved a stop at Margarita, as Bertodano had learned during his tenure in the former province. Moreover, although there was no political or fiscal connection between the two, there was an important ecclesiastical bond linking both provinces: Cumana fell under the jurisdiction of the bishop of San Juan in Puerto Rico. Having received a licence to travel to Santo Domingo from his father-in-law, del Moral proceeded from Puerto Rico to Hispaniola, where the Audiencia became wary of his travelling from port to port seemingly without a justifiable motive.Footnote155

Although the Audiencia then ordered the governor of Santo Domingo to detain del Moral in the city, the governor granted him further licence to leave for Spain, provably through López de Morla’s influence.Footnote156 Having lost its jurisdiction over the affairs of Caracas with the creation of the viceroyalty of New Granada, the Audiencia had intended to delay del Moral’s departure while it informed its counterpart in Santa Fe of its misgivings about the former acting accountant of Caracas. But the informal political network of the Bertodano-Kneppers seems to have allowed him to outmanoeuvre the Audiencia.

Thus, del Moral was able to benefit from political protection through the network created by the marriages of the Bertodano-Kneppers, eventually reaching Madrid and securing a further appointment to Caracas.Footnote157 In this light, it is easy to see the marriage and settlement patterns of the Bertodano-Knepper sisters as the result of a strategy to articulate a family network that linked multiple ports in the Caribbean, although this probably overplays the extent to which any such network is fully the result of calculated decisions. More significantly, perhaps, whether created deliberately or not, the network they became part of – linking Caracas to Cumana, Margarita, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo and Cartagena de Indias – highlights the informal bonds that tied together the Spanish world beyond and across the official channels of royal, ecclesiastical and fiscal administration.

It is perhaps within the context of this same network that we should interpret the accusations of involvement in illicit trade made against Bertodano and María Juana Knepper in Puerto Rico and Cartagena de Indias. In 1723, authorities in Madrid received almost at the same time Bertodano’s residencia as governor of Puerto Rico and some worrying reports from Cartagena de Indias. The judge who led the enquiry into Bertodano’s tenure in Puerto Rico found reason to suspect that Bertodano had been actively engaged in illicit trade. The ninth charge brought against him accused Bertodano of tolerating the trade of cattle and pork from the interior of the island for foreign goods and of engaging in the sale of the latter inside San Juan through several accomplices.

The accusations also included María Juana: by some accounts, her name was used to legitimise the sale of foreign textiles by Bertodano’s agents, claiming they were her licit property; by others, she was directly involved in the operation, instructing her husband’s associates what to buy and what price to sell it for.Footnote158 Around the same time as the record of Bertodano’s residencia trial from Puerto Rico reached Madrid, Andrés de Pez, the president of the Council of the Indies and secretary of state for American affairs, received reports from merchants recently returned to Cadiz from Cartagena de Indias claiming that María Juana and Bertodano had continued to engage in illicit activities in their new posting. Allegedly, María Juana had been acting as an intermediary between her husband and foreign merchants, particularly British and Dutch ships whose captains were able to purchase the governor’s acquiescence to unload illicit goods through his wife.Footnote159

As is often the case with accusations of involvement in illicit trade, there is no way to prove whether Bertodano and Knepper were guilty. But there is plenty of reason to believe they were. Bertodano had first been accused of tolerating and profiting from illicit trade shortly after the start of his tenure in Cumana.Footnote160 During his time in Caracas, at least one person had accused Teresa Cecilia’s second husband, Álvarez de Abreu, of knowingly allowing his brother and associates to offload contraband goods from New Spain and the Canary Islands into the city with the governor’s connivance.Footnote161 Thus, it is not surprising that the judge in Bertodano’s residencia trial in Puerto Rico should suspect both the governor and his wife of participating in illicit trade, or that the couple should have been accused of engaging in the same practices in Cartagena de Indias.

In the latter port, moreover, there are other indications that the family remained strongly linked to contraband trade even after Bertodano’s tenure as governor came to an end: María Juana’s will, written shortly before her passing, was witnessed by two members of the Nárvaez y Berrio family, relatives of the Conde de Santa Cruz de la Torre, an influential member of Cartagena’s elite, rumoured to control an important network distributing foreign contraband from the port to the New Granadan interior.Footnote162 Only months after María Juana’s passing, her eldest son would marry a niece of Santa Cruz de la Torre.Footnote163

In the end, although the accusations made against María Juana in Cartagena de Indias fit well with the couple’s track record and with the network built through their daughters’ marriages, the case against her fell apart: of the two key local witnesses, one died before a formal enquiry was launched and the other took refuge in a monastery to avoid ratifying his statement.Footnote164 By then, however, the damage had been done. Whatever its material benefits may have been, María Juana’s alleged involvement in foreign illicit trade ultimately hindered more than helped Bertodano’s professional career in the royal service. The accusations made against the couple in Puerto Rico and Cartagena de Indias, although never legally proven, were part of the justification used by the Council of Indies to remove him from office in 1724, effectively ending his career as a soldier and provincial governor.Footnote165

If, as it seems likely, María Juana was involved in illicit trade, mediating between foreign merchants and her husband, perhaps facilitating the funnelling of British and Dutch goods through the network articulated by her daughters’ marriages, she would have simply been engaged in an activity that was endemic to the region and, by some accounts, a lifeblood for some of the more isolated places in northern South America and the Caribbean.Footnote166 Illicit inter-imperial trade bound the circum-Caribbean region together well across the territories claimed by different European powers. The activities and connections built by the Bertodano-Knepper women suggest that we need to further stress the role women played in these activities.

Finally, when Bertodano’s assets were seized in Caracas in 1716 as part of the investigation into his role in obstructing the trade of the Honduras Company, his daughters and their husbands played a key role in protecting his property. Teresa Cecilia claimed ownership of a silver tea service Bertodano used regularly in his role as interim governor. The set, it was argued, had actually belonged to Riba Herrera and constituted part of his daughters’ inheritance; Teresa Cecilia allegedly had lent it to her father, as she had no immediate use for it.Footnote167 Whether the claim was true or not, it prevented the most valuable item in Bertodano’s household from being seized.

Similarly, when Bertodano’s property was first inventoried, the agents of the Honduras Company noticed there were no enslaved persons listed, despite the governor’s household including, as we have seen before, eight of them. Eventually, further investigations resulted in Bertodano claiming that one of his enslaved servants had recently died, two more had been given as part of María Josefa’s dowry upon her marriage to Vega Arredondo, a further bondsperson had been given as a present to Elena Juana and Jerónimo del Moral to help them settle in Caracas, and one more allegedly belonged to the governor’s eldest son, who was barely a teenager at the time.Footnote168 The judge who had ordered Bertodano’s property seized, was unconvinced by the claims and suspected that all the enslaved individuals, who until recently had served in Bertodano’s house, were actually his property. However, claiming he did not have time to investigate the matter further, he delegated the enquiry into the former governor’s assets while continuing his work investigating the obstacles faced by the Company.Footnote169

Whether the claims that María Josefa’s marriage and Elena Juana’s relocation from Madrid to Caracas had led to a redistribution of the family’s assets were true or not, Bertodano’s daughters played a key role in an attempt to protect their father’s – or the family’s – property from seizure. Under Spanish law, women, even when married, were entitled to own property and their dowries, even if administered by their husbands, enjoyed special legal protection.Footnote170 Bertodano’s sons-in-law also played a key role in protecting those resources. The person appointed to further investigate whether Bertodano had hidden any other assets was Antonio José Álvarez de Abreu, whose marriage to Teresa Cecilia Bertodano Knepper had not yet been made public.Footnote171 Álvarez de Abreu conducted a perfunctory investigation that, perhaps unsurprisingly, failed to find any other concealed property.Footnote172