ABSTRACT

This study analyzes intersections between penal deportation and Indigenous captivity in southeastern South America during the eighteenth century. Via records on Lincompani, a cacique taken captive in the southern borderlands of Buenos Aires and exiled to the Malvinas Islands alongside other prison laborers (presidiarios), it highlights the scale of penal deportation within the early Americas and connects the practice to the formation of geopolitical borders. As colonial officials banished purported criminals to borders, rather than across them, and banished male Indigenous captives from one borderland to another, these forced migrations reinforced territorialized spatial logics and contributed to Indigenous land dispossession. Drawing upon a half century of records from Malvinas, the article also analyzes convicts' and captives' experiences of penal deportation, highlighting instances when their shared status as presidiario may have superseded or been subordinated to ethnic distinctions, considering the gendered logics that shaped their banishment, and reflecting upon the narration of their actions via colonial records.

Introduction

In the eleven years that Lincompani had worked as a rancher on the Isla de la Soledad, the largest island in the Malvinas archipelago, he had spent little time in its small hospital. This was more likely due to a lack of medical care than a lack of personal need. At 72 years old, he was far more advanced in age than the others alongside whom he labored, and just three years earlier, in 1788, the island’s commanding officer had deemed him “entirely useless” due to his age and ailments. Despite this determination, Lincompani was forced to continue in his labor, and now a fall from horseback had left him “entirely unfit.” The island’s doctor diagnosed him with two fractured ribs and intermittent bleeding from one of his ears, likely a sign of head trauma, and a year later he returned to, or perhaps remained in, the hospital with soreness in his chest due to the “thump he received from being hurled.”Footnote1

While these brief medical diagnoses weighed Lincompani’s suffering on a scale of productivity, a seven-page plea for clemency drafted with three other prison laborers (presidiarios) and sent to the Spanish viceroy in Buenos Aires in 1792 painted a fuller picture. In this letter, Manuel Lorenzo, which may have been another name for Lincompani, and the others contrasted the hopelessness of their life sentences with the comings and goings of presidiarios serving a fixed term. Having already spent over a decade laboring intensely in the propagation of cows and horses amid the island’s whipping winds and cold temperatures, they were riddled with ailments that they believed could only be relieved elsewhere. They pointed out that in all this time, each one had followed the island’s strict military protocol and not once had any of them committed a crime. They expressed desperation at the prospect of living the rest of their days in an island where even the commanding officer acknowledged that their quality of life “called into question the humanity [of their exile].” If only the viceroy would set an end date to their punishment, they pleaded, the hope of eventually being reunited with their families would mitigate the “many stresses” with which they were living.Footnote2

At first glance, Lincompani’s experiences and actions in Malvinas resembled those of other presidiarios. Records from the island certainly portrayed him that way: like most others, he was almost always labeled a presidiario or an exile (desterrado), during the day he roamed widely about the island to propagate livestock, at night he slept locked within the island’s fort (presidio), he received regular rations, and he periodically reported to the rotating military personnel who governed the island. Yet small annotations indicate a different experience. In several rosters of the island’s presidiarios, Lincompani was labeled a “Pampas Indian” or simply an “Indian,” making him one of a small number of Indigenous captives exiled to the island alongside purported criminals. Since Lincompani was a captive, rather than a colonial subject who had been arrested, he had never had formal proceedings, his banishment was interminable, and he was sent to Malvinas at around sixty years old while most other presidiarios were in their twenties or thirties. Lincompani’s captivity left him devoid of a casefile (expediente) that would clarify his name and identity to the islands’ rotating administrators and to present-day researchers, and this archival circumstance has contributed to the erasure of this part of his life from historical memory.

Indigenous men who, like Lincompani, were taken captive and exiled to penal establishments have occupied a liminal space between historical studies of penal colonization and borderlands scholarship that is focused on Indigenous captivity. These two bodies of scholarship nonetheless provide a useful starting point for understanding the captives’ ordeals. In recent decades, studies on penal colonization have revealed the systemic nature and historical longevity of the practice, linking penal deportations to the expansion of imperial projects and capitalist labor extraction and demonstrating the persistence of the practice long after political independence from European empires. Estimates vary widely, yet most works agree that hundreds of thousands of people were transported to and within the Americas in this way, with global estimates in the millions.Footnote3 These works have framed penal deportation principally in terms of imperial utilitarianism – as a means for European crowns to simultaneously enforce social order in metropoles while providing colonial authorities a portable labor force – and have focused on deportation from administrative centers to borderlands.Footnote4 As a result, discussion of the Indigenous presidiarios remains limited. Some works have identified them via quantitative convict profiles, and some have analyzed instances of Indigenous colonial subjects who were entrapped in or participated in the practice of penal deportation.Footnote5 Yet, little has been written about the experience of Indigenous men once sent to a presidio, as they comprised an ostensibly small percentage of presidiarios and their documented social status (calidad) as presidario or desterrado tended to supersede ethnic or phenotypical markers in colonial records, making them often indistinguishable from other exiles.

Meanwhile, a growing number of borderlands studies and ethnohistorical works have analyzed Indigenous captivity in the Americas. In emphasizing interethnic exchange and overlapping networks of kinship, trade, and authority among imperial and Indigenous agents, these works have paid increased attention to the persistent abduction, forced relocation, and enslavement of Indigenous peoples despite formal prohibitions by both Iberian monarchies.Footnote6 Some scholars estimate that as many as five million Indigenous Americans were enslaved, yet hemispheric tallies tend to derive from Anglophone studies of mainland North America and the Caribbean, with less attention to lowland South America.Footnote7 Amid a focus on land dispossession and the distribution of captives to colonial individuals or families, the deportation and use of captives for state labor has received little attention, and when mentioned, deportation has tended to appear as a postlude to narratives focused on captives’ homelands and individuals who remained in borderland spaces.Footnote8 This tendency likely derives from the methodological challenges of connecting fragmentated and geographically dispersed archival records on captives. Colonial records regarding sites of abduction tend to be located in different archival repositories or collections than records regarding sites of deportation, and often in different countries, making it difficult to track captives across their journeys.Footnote9 This challenge is particularly acute when considering the tendency for colonial writers to replace ethnic labels with general labels of calidad and to assign common Catholic names to captives, thereby occluding captives’ origins.

The present study addresses the penal deportation of Indigenous captives in southeastern South America, a region commonly referred to as the Río de la Plata. It examines the colonial logics that undergirded the practice alongside the individual and collective experience of Indigenous captives, their co-exiles, and their home communities. Considering captives and convicts together reveals the intersection of migrations that are most often conceptualized separately and enables us to rethink common assumptions. Penal deportation was not merely a utilitarian strategy to enforce metropolitan law and acquire colonial labor; via the forced relocation of both convicts and captives, it was also a means to produce a hierarchy of spaces of colonial order, from established cities to newly formed borderland settlements to lands beyond a given jurisdiction’s control. The construction of colonial spaces involved the policing and punishment of plebeians, nonconformists, and increasingly racialized subjects, whose punishment via exile made them an unfree embodiment of colonial sovereignty in contested borderlands. Meanwhile, the deportation of Indigenous captives by colonial officials constituted a double exertion of sovereignty and land possession: their abduction was an assertion of colonial authority over people outside colonial jurisdictions, and their forced relocation was a means of using their bodies to claim other contested lands. Thus, in taking Lincompani captive, colonial Spanish authorities claimed the right to police borderlands that they contested with his kin, and in deporting him to Malvinas they sought simultaneously to transform him into a colonial subject and to reinforce Spanish claims over the archipelago vis-à-vis Great Britain.

Lincompani’s biography is integral not only to understanding colonial logics of deportation but also for the meaning derived from his documented actions. He and other presidiarios appear intermittently in Spanish colonial records from the Malvinas Islands from 1766 through 1810, and sometimes in judicial proceedings, military correspondence, and administrative records from the South American mainland. These records are dispersed across provincial and national archives in Argentina and Uruguay as well the Archivo General de Indias in Spain. Taken together, however, they enable narrative accounts of Lincompani’s captivity and the entangled experiences of presidiarios, Indigenous and otherwise. These individual and collective stories illustrate the ambiguities of colonial records – in particular, patterns of registering, naming, and classifying – and the difficulties of tracking Indigenous captives across a polycentric colonial apparatus. Nonetheless, attention to this corpus of documents allows for the consideration of lives largely erased from memory via deportation and archival fragmentation, and, in turn, enables narrative frameworks that do not end at the moment of abduction or sentencing, even if the result is holographic accounts.Footnote10 Indigenous captives’ lives continued after penal deportation, and their relations with convicts reveal both solidarity and antagonism in the panorama of responses to their shared predicament.

From cacique to presidiario

Lincompani was abducted by Spanish colonial authorities in 1780, when he and a companion named Valerio traveled to Luján, a settlement about fifty miles west of the city of Buenos Aires, to seek a peace accord with the viceroy.Footnote11 This was not his first meaningful encounter with the Spanish, as mobile encampments of autonomous Indigenous people (tolderías) under his authority had participated in a joint expedition against Tehuelches in 1770 and ratified a peace agreement with the Spanish the following year.Footnote12 Moreover, Lincompani’s tolderías lived along the pathway from Buenos Aires to Salinas Grandes – salt flats that were integral the city’s growing ranching economy – and they therefore had regular interactions with military officials, merchants, and settlers.Footnote13 While Spanish administrative records provide few details about Lincompani’s detainment, they do include the viceroy’s rationale for giving the order that he be taken into custody. After consulting with military officials, administrators, and elites from nearby settlements and taking testimony from a former captive, the viceroy concluded that Lincompani’s solicitation of peace was a ploy to “put our vigilance to sleep and hinder our [defensive] measures.”Footnote14 He pointed to an ongoing conflict with nearby tolderías as evidence of the cacique’s deceit, even though tolderías in question were most likely not under Lincompani’s leadership. He decided that it was “not in our interest to offer a truce … even when those caciques proceed in good faith” and determined that existing laws and customs that had governed interethnic relations in the region were “truly unintelligible”. He resolved to prioritize instead the “law of self-defense”.Footnote15 Months later, Spain’s Consejo de Indias affirmed the viceroy’s decision, claiming that “there were insufficient means to discern the strength of [interethnic] pacts” and reiterating suspicions of Lincompani’s duplicity.Footnote16 Yet, Spanish officials provided little justification for Lincompani’s and Valerio’s detention and exile, and the viceroy merely noted that it would “remove one of the most expert caciques [in knowledge of local lands] from among the Indians.”Footnote17 The opportunistic nature of Lincompani’s banishment to Malvinas is especially clear when considering that the viceroy and his war council unanimously declared that they would pursue peace with tolderías from the pampas the following year, a decision the Spanish Crown deemed “prudent”.Footnote18

Penal deportation was ubiquitous with Ibero-American ultramarine expansion and colonial administration and an omnipresent threat to imperial subjects, particularly plebeian men. Much like other European imperial governments, Spain and Portugal collectively banished over a hundred thousand purported criminals overseas or across their respective colonies, and tens of thousands of them were deported to, across, or from the Americas.Footnote19 Existing efforts to calculate scale have focused on exiles (desterrados/as in Spanish; degredados/as in Portuguese) banished from the Iberian mainland to the Americas or, in the case of Spanish America, from New Spain to presidios in its northern borderlands, the Caribbean basin, or the Philippines.Footnote20 Increased accounting of the geographical networks of deportation, particularly in southern South America, indicates that these numbers were higher than originally assumed.Footnote21 Moreover, penal deportation intersected with other networks of forced migration, as it was an avenue for colonial officials to punish enslaved Afro-descendants accused of rebelliousness or other offenses or to deracinate Indigenous captives, as occurred with Lincompani and Valerio.Footnote22 In numerous borderland establishments in southern South America, presidiarios lived alongside peasant families who had been forced or compelled to migrate from Spain or from other parts of Spanish America as part of Bourbon-era settlement projects.Footnote23

In southeastern South America, penal deportation and border making grew as concomitant practices during the latter half of the eighteenth century, and each derived from a colonial desire to effectuate a new spatial order in the region. Whereas imperial legal geographies and population centers had long been restricted to coastal and riverine corridors and surrounded by autonomous Native polities, Iberoamerican officials began to superimpose claims to sovereignty upon ever-expanding claims to land possession of continental interiors.Footnote24 Shifting administrative geographies shaped both the process and destinations of banishment. The formation of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776 centralized Spanish colonial administration in the region in Buenos Aires, brought numerous districts under its jurisdiction, and overlaid them onto more localized administrative units, such as town councils.Footnote25 Since each jurisdictional body had the capacity to banish someone, decentralized and parallel systems of justice emerged.Footnote26 In many cases, banishment was a relatively local affair, with condemned individuals expelled from a given jurisdiction rather than to a particular destination.

Cases of outward banishment from a district’s jurisdiction occurred alongside others in which the accused was sentenced to a public works project or a presidio. This pattern mirrored other parts of Spanish and Portuguese America and likely explains the often-interchangeable use of desterrado and presidiario in colonial records.Footnote27 Some presidios were adjacent to administrative centers, namely Buenos Aires and Montevideo, yet most were located along contested borderlands. Most desterrados banished by colonial authorities in Buenos Aires were sent to fortified coastal sites like Maldonado to the north (contested with the Portuguese); tiny settlements like Carmen de Patagones, Puerto Deseado, and Floridablanca southward along the Patagonian coast (contested with Aucas and Tehuelches); and island military establishments like Martín García (contested with the Portuguese) and Puerto de la Soledad in the Malvinas Islands (contested with Great Britain) (Map 1). Small numbers of desterrados were banished to more distant locations like Fernando Póo (present-day Bioko, Equatorial Guinea) and the Philippines.Footnote28 In these instances, the sentencing institution – whether a town council, district judge, governor, audiencia court, magistrate (alcalde), military officer, church official, or otherwise – determined the length of banishment, while the viceroy generally chose the destination and sometimes modified or added punishments.Footnote29 In other instances, local administrators banished individuals to newly formed borderland forts at the edges of their jurisdiction, and thus the geography of banishment grew side-by-side with attempts at territorialization.Footnote30

Map 1. Settlements and Sites of Penal Deportation. Administrators in colonial settlements (dots) banished purported criminals to numerous destinations (stars) throughout the region. Presidios along Buenos Aires’s southern borderland (squares with flags) and elsewhere were simultaneously sites of deportation and where Indigenous captives were routed into penal systems.

If the trajectories of desterrados replicated and reinforced jurisdictional geographies, their purported crimes further demonstrate how colonial officials readily wielded banishment to control the movement of people and property. Based upon administrative records from the Malvinas Islands and Martín García, housed in Argentina’s Archivo General de la Nación, there were approximately 1000 men banished to these two locations – 250 to the former and 750 to the latter – from 1766 to 1810. Although the islands’ records do not identify the alleged crimes of about half of the exiles, theft, smuggling, vagrancy, and desertion – often wrapped up in the same description – accounted for about half of cases in which a crime was identified, for a total of about 250. Violent crimes (murder, causing death or injury) were the next significant grouping, with about 84 cases, and the remainder included cases of sexual nonconformity (sodomía, adultery, cohabitation, double marriage), sexual violence (sex with a minor, rape), and general categories (excesses, disobedience).Footnote31 Comparing these numbers with those of the capital jail in Buenos Aires, the holding center that most penal exiles passed through prior to being sent to Malvinas or Martín García, reveals a similar pattern. From 1776 to 1783, 1555 people were imprisoned there, of which one quarter were accused of theft, one quarter of murder, one tenth of transgressions against sexual mores, one tenth of violating public order, and the rest of a variety of offenses or via extrajudicial means.Footnote32

The preponderance of punishment for crimes against property, which generally involved the extraction or unsanctioned transfer of livestock, dovetailed with colonial efforts to promote ranching and proliferate bovine cattle as private or state property. Likewise, punishments for vagrancy tended to target transient or mobile men and communities, many of whom had migrated from other population centers and whom colonial officials deemed unproductive and disorderly. In 1789, for example, the town council of the provincial city of Santa Fe ordered district judges to “pursue and exterminate all thieves and pernicious people” and offered to send them to whatever establishment the viceroy saw fit. The following year, the town council expelled families who had come from Córdoba and Santiago del Estero for being “vagrants and pernicious,” as they had settled without official license.Footnote33 The Governor of Buenos Aires issued a similar order in 1750, as did the viceroy in 1770.Footnote34 The banishment of men accused of thievery or vagrancy was a logical choice for administrators, as the principal labor assigned to exiles in Martín García and Malvinas was the introduction and propagation of livestock, a task that was both physically onerous and predicated upon experience on ranches. From an administrative perspective, it served the dual purpose of making the two colonial sites materially viable and reforming those convicted of theft or vagrancy via forced manual labor. This belief in reformation via labor derived from the Bourbon-era notion that industriousness was a condition of masculine honor, which was used to police and exploit the labor of plebeian men even amid a scarcity of jobs.Footnote35

The colonial administrative apparatus that shaped geographies of banishment was superimposed upon a much broader Indigenous geography in the region. Despite claims espoused by colonial administrators, through the end of the eighteenth century the majority of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata remained Native ground. Strings of colonial settlements were surrounded by autonomous Indigenous polities – including those labeled Pampas, Serranos [or Pampas Serranos], Aucas, and Ranqueles south and west of Buenos Aires; Aucas and Tehuelches further south in Patagonia; Charrúas and Minuanes north of Montevideo and east of Santa Fe and Corrientes; Abipones and Mocovíes between Santa Fe, Corrientes, Santiago del Estero, and Córdoba; Diaguitas and Calchaquís near Tucumán; and Mapuches and Pehuenches near Mendoza – who effectively controlled rural regions (Map 1). Rather than being organized around these ethnic labels, which were colonial classifications, Indigenous polities tended to be structured around tolderías under the leadership of one or several caciques. Lincompani, for example, shared leadership with another cacique known as Cachegua.Footnote36 Political relations among tolderías were dynamic, in large part due to long-distance networks of cultural and economic exchange, and their approaches to colonial settlements derived from long-standing patterns of Indigenous diplomacy in the region.Footnote37

Exiles arrived to borderlands as presidiarios or as conscripts within companies of mounted guards known as blandengues, who patrolled the lands between settlements and often raided tolderías.Footnote38 Meanwhile, military deserters from these borderlands and Indigenous men abducted in colonial raids found themselves transported to forts in other corners of the viceroyalty, following a pattern evident throughout the Americas at the time.Footnote39 Rosters from the city jail in Buenos Aires and from Martín García confirm the presence of Native men who appear to have arrived through captivity.Footnote40 Banishing Indigenous captives was a colonial practice that had deep roots in the region. For example, as early as 1629, the Governor of Buenos Aires sought royal permission to banish captives from the Chaco to Brazil.Footnote41 By the eighteenth century, colonial efforts to establish unilateral territorial control over continental interiors made Native removal a centerpiece of borderlands policy, and these policies were a precedent for the genocidal campaigns undertaken by republican armies in the nineteenth century. Over time, captivity and banishment became one of the central means through which autonomous Native people were incorporated into systems of colonial and state domination.

The fate of Indigenous captives within colonial systems of punishment depended in part upon an individual’s perceived gender and age. Following a pattern of punishment wielded against imperial subjects, Indigenous women and children most often faced cloistering in Buenos Aires’s casa de recogidas or were distributed among elite families as domestic servants while Indigenous men were sent to public works or deported to distant presidios or mobile galleys. This gendered and age-based bifurcation sought to exploit Indigenous labor, to undermine Indigenous reproduction, and to separate Native men from colonial subjects who were women. It also derived from Spanish colonial notions that women and children could be reformed via Catholic tutelage.Footnote42 In part for this reason, captive women and children were often sent to Jesuit-Guaraní missions in Paraguay, as occurred in 1728, when Guarani militias from the missions reportedly abducted Charrúa women and children near Corrientes.Footnote43 Likewise, in 1745, when colonial raiders took 96 captives from tolderías near Luján associated with a cacique named Calelián, they sent women and children to the missions while transporting men to the presidio of Montevideo and then aboard El Asia, a ship destined for Spain. Soon after their embarkation on the ship, the men staged an uprising, and briefly held the quarterdeck, before being overcome and throwing themselves to the sea.Footnote44 Five years later, one of Calelián’s wives, Leonarda, escaped from the missions to Santo Domingo Soriano with another woman and a child. They were purportedly coordinating with several Spanish settlers to return to the Pampas when their plan was uncovered by local authorities.Footnote45

Although captives comprised a small percentage of desterrados, the use of deportation as a political strategy and means of punishment makes them integral to understanding the logics of banishment. From the perspective of colonial officials, banishment was part of a broader effort at eliminating Indigenous neighbors and claiming their lands. This relationship is evident in the commonly used threat to “exterminate” (exterminar) Native people who refused to submit to Ibero-American colonial authorities or cede their lands. While present-day definitions of exterminar emphasize wholesale killing, its principal meaning in both Spanish and Portuguese through the nineteenth century was to “expel beyond the borders” of a province or kingdom, a meaning derived from the Latin roots ex- (“out”) and terminus (“boundary”). Contemporary dictionaries marked it as synonymous with desterrar (“to banish”).Footnote46 Therefore, when the leader of an 1801 Spanish commission to Minuán tolderías threatened to “exterminate [your] malignant, inhuman, and harmful race,” he was implying both killing and territorial removal, actions that the Spanish undertook simultaneously.Footnote47 Across the Andes, when the governor of Chile wrote to the crown in 1767 that he sought to “annihilate” (aniquilar) Mapuches who resisted colonial settlements, this meant “removing all of them from their lands and distributing them throughout the kingdom [of Chile] … distributing women and children among the kingdom’s haciendas.”Footnote48 Though aniquilar explicitly meant to “reduce something to nothing,” here too expulsion from their lands was the mechanism.

Captivity and exile were broadly disruptive to the multiethnic alliances that characterized Indigenous social organization in borderlands, as personal relations structured the political landscape. It is therefore unsurprising that colonial officials used banishment as a strategy and that captives’ kin frequently fought for their return. The southern border of Buenos Aires, shared with Serranos, Aucas, Ranqueles, and other Native peoples – collectively labeled “Pampas” in many colonial records – is instructive in this regard. Between the 1760s and the early 1780s, relations between colonial officials, settlers, and inhabitants of neighboring tolderías fluctuated between peace and conflict. Newly formed settlements, the militarization of borderlands, shifting interethnic alliances, and colonial attacks often generated Indigenous reprisals (malones), while ever-changing economic conditions and periodic environmental crises resulted in competition for resources.Footnote49 Amid such shifting relations, numerous caciques were taken captive and sent to Montevideo or Malvinas, just like Lincompani. For instance, a cacique named Flamenco collaborated with Spanish militias from at least 1759, brokered peace between the Spanish settlement of Luján and nearby tolderías in 1765, participated in a malón against a new settlement in Magdalena in 1768, sought to form a settlement near El Zanjón in 1769, and protested the attacks against Tehuelches that Lincompani’s tolderías participated in 1770.Footnote50 During this last incident, he was arrested by the Spanish and jailed in Buenos Aires. He was banished to Malvinas the following year, where he remained until 1778, when he was transferred to Montevideo. Flamenco returned to Buenos Aires in 1784, per the viceroy’s orders, to serve as a guide in an expedition against tolderías.Footnote51

The captivity of Indigenous leaders often led their kin to demand their return or to seek reprisal. Following Flamenco’s imprisonment, his son, Antuco, approached colonial officials on several occasions, only to find himself and four others taken captive and sent to Malvinas as well.Footnote52 In 1774, when a Ranquel cacique named Toroñan went to Buenos Aires with dozens of his kin to sell artisanry in the city’s markets, they were taken captive and banished to Montevideo. The viceroy declared Toroñan and twenty men presidiarios and ordered that they serve life sentences in the city’s fortifications. He allowed Montevideo’s governor to determine where to send the seven women who were also taken captive. Other Ranqueles repeatedly demanded that Spanish officials return Toroñan and the others until at least 1781, and they refused to make peace with the Spanish until the captives were restored to their homelands.Footnote53 None of the demands were met with restitution in this particular instance, but they nonetheless formed part of a broader pattern of borderland relations, as the return of other captives taken to Buenos Aires was a common feature of peacemaking in the region.Footnote54 Similar dynamics played out throughout the region, including in 1754, when three Abipones from the Chaco region were banished to Montevideo and pressure from their kin forced the lieutenant governors of Santiago del Estero and Santa Fe to facilitate their return.Footnote55

Surviving banishment

Nine years after arriving on Malvinas, Lincompani was baptized, and just two weeks later, Valerio was as well. Records relating to their baptisms, which included correspondence between the island’s commanding officers and the viceroy in Buenos Aires, provide limited information regarding the circumstances of these events. The date of the baptisms – 11 January 1789, for Lincompani and 25 January 1789, for Valerio – were both Sundays, indicating that the sacrament was a public display as part of the island’s weekly mass. As part of their baptism, each received a Catholic name: Lincompani was named Pedro Apóstol Juan Lincompani and Valerio was named Pedro Apóstol Joseph Valerio.Footnote56 The meaning of the event to all involved is murkier and requires speculation. The island’s military officers and the viceroy presented it as evidence of the tireless labor of the chaplain stationed there, and the use of the ethnic label “Pampas” throughout these particular records underscored a narrative of spiritual conquest. Yet these records do not speak to the motivations or coercion that led Lincompani and Valerio to receive baptism a decade after their arrival, the timing of the events, or the significance of naming for the two men.

The issue of naming is particularly salient, both for its symbolism and for the obstacles it poses for identifying Lincompani and Valerio across historical records. While the exact meaning of Lincompani is unclear, eighteenth-century records and nineteenth-century dictionaries suggest that “Lincon” may have meant “cricket” (grillo), and “pani” may have meant “radiance” (resplandor).Footnote57 Lincon was a name used to refer to several caciques in the Pampas at the time, which suggests that it may have been a marker of status or lineage as well. That Lincompani would be relegated to his last name and thereafter he would be regarded as Pedro Juan was significant, as it marked him as Catholic subject rather than an Indigenous authority. The shift in recorded names also hinders the identification and interpretation of his actions during his captivity. Lincompani’s name was recorded in records from Malvinas in myriad ways, including as “Lincompagni,” “Licon Pagni,” “Lincon Pagny,” “Licon Sagny,” “Lorenzo Licompani,” “Sirco Pagni,” and potentially “Manuel Lorenzo.” These myriad names resembled those of other caciques in the pampas and presidiarios in Malvinas, and baptism only compounded the ambiguity.Footnote58

Even colonial officials struggled to match the names with a person, and their confusion carried significant consequences. In a letter to the Governor of Montevideo in 1793 regarding a list of pardoned presidiarios, the viceroy suggested that Lincompani must be “the one that you named Santiago Pani, as I cannot find who else among those pardoned it could be … his actual true name is Manuel Lorenzo Maria de la Soledad, according to a roster [from 22 November 1791].”Footnote59 A criminal casefile from 1780 reveals instead that Santiago Pani was an Indigenous man (indio) who had been convicted of homicide.Footnote60 Moreover, the roster cited by the viceroy distinguished Lincompani from Manuel Lorenzo Maria de la Soledad and marked Lorenzo’s baptismal date as 1 January 1791, two years after Lincompani’s.Footnote61 Similarly, a list of presidiarios from May 1791 distinguished Lincompani, Santiago Pani, and “Manuel Lorenzo” as separate people with different dates of arrival – Manuel Lorenzo and Lincompani in January and February 1780, respectively, and Santiago Pani in 1783 – and earlier rosters from 1781 and 1782 distinguished “Lorenzo Yndio Pampa” from the “Yndio Pampa Linco Pagni.”Footnote62 A January 1780 letter from the commanding officer in Malvinas to the viceroy confirmed the arrival of an “Yndio Pampa Lorenzo” that month, while the oft-cited cacique Lorenzo (also known as Calpisquis) remained in the pampas until 1784 and an “indio Lorenzo” was reportedly detained in Montevideo’s presidio in 1786.Footnote63 These sources seem to indicate that the conflation of “Lorenzo” and “Lincompani” occurred in Malvinas, yet military records from the pampas indicate that “Lorenzo Licompani” was a name that had been ascribed to him prior to his exile.Footnote64 For his part, Valerio often appeared as “José Valerio” or “Joseph Balerio” until receiving his baptismal name.

This ambiguous naming permeated historical records regarding Lincompani and, by extension, historical studies that attempt to account for his actions prior to his exile. Studies from the past three decades, in replicating orthography from historical documents or from other historical scholarship, have named him “Lincopagni,” “Linco Pangui,” “Lincon Pangui,” “Linco Pagni,” “Licon Pagni,” “Lincopán,” or simply “Lincón.”Footnote65 This has at times led to confusion over whether certain actions ascribed to his father were really his own.Footnote66 Similar patterns are evident when considering the labels used to describe him, which ranged from ethnonyms, such as Pampa, Auca, and Ranquel, to terms that marked Indigeneity and status, namely indio and cacique. The ambiguities, colonial origins, and geographic significance of ethnic labels in the region have been discussed in detail elsewhere, but it is worth noting that upon Lincompani’s and other captives’ arrival to Malvinas, the only ethnic label used to mark them was Pampa, which was used intermittently alongside the racial label indio. The marker of leadership, cacique, disappeared entirely.Footnote67 This individualization and discursive disassociation from his kin – the labels no longer signified who he represented but instead marked his Indigeneity – coincided with the transformation of his name via baptism and the subordination of his ethnic status to that of presidiario or desterrado.

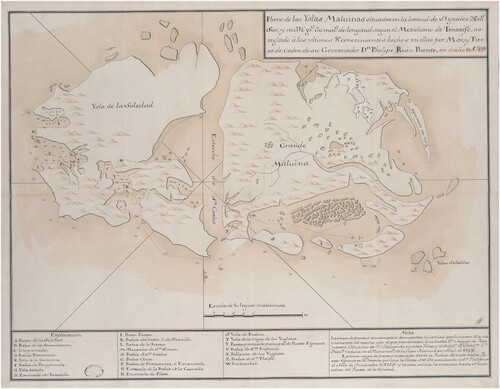

The discursive transformation from cacique to presidario points to a shared status between Lincompani and other exiles via the experience of banishment. Regardless of ethnic origin or the circumstances of their banishment, presidiarios transported to Malvinas carried out a shared set of tasks, followed similar routines, and faced the same restrictions.Footnote68 The principal labor required of presidiarios in Malvinas was to care for and propagate livestock throughout the Isla de la Soledad, a task that at times took them far away from the military barracks in the Puerto de la Soledad (Map 2). In his remitting of Lincompani and Valerio to Malvinas, the viceroy in Buenos Aires recommended this exact task.Footnote69 Yet, by evening, presidiarios were required to return to their barracks and remain there until morning. Failure to return to their barracks each evening was at best a cause for suspicion and at worst, according to records from criminal investigations on the island, evidence of guilt and a punishable offense.Footnote70 Extant records provide fewer details regarding weekly routines, aside from mass on Sunday mornings, but it is likely that remaining days were occupied with pastoral activities. There is little evidence to verify the extent to which such routines were enforced, though they do provide glimpses of a structure of surveillance. For example, certain presidiarios in good standing with the island’s officials were named overseer (capataz) and placed in charge of others. Investigations into crimes that occurred on the island and involved presidiarios indicate that the capataz was in charge of assembling the presidiarios upon command and that this individual spent their evenings in a room adjacent to the presidiarios’ main quarters.Footnote71 In these brief snippets of information, Indigenous captives like Lincompani appeared alongside other presidiarios, sharing the same quarters, fulfilling the same expectations, and being relied upon for the same information.

Map 2. “Plano de las Yslas Maluinas” (1769). The Spanish military establishment of Puerto de la Soledad (letter A, far left) was located on the Isla de la Soledad along the Bahia de la Anunciacion (letter B). Spain’s military maintained detailed information regarding coastlines, yet demonstrated less knowledge of the island’s interior, where presidiarios frequently labored. Source: España. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Archivo General de Indias, MP-BUENOS_AIRES,82BIS.

Notwithstanding their shared routines, requirements, and expectations, differences existed between the experiences of Indigenous captives and those of presidiarios condemned by colonial courts. Distinctions began with sentences, as the longest sentence for most imperial subjects – Indigenous or otherwise – was ten years, while nearly all Indigenous captives were transported with no time limitations or legal proceedings. In the case of Malvinas, there were only several exceptions to this rule: a thirteen-year-old boy who was convicted of sodomía, a Paraguayan man accused of being a recidivist thief, two men accused of spying for Indigenous enemies, and an Indigenous subject accused of treason.Footnote72 The first two cases were built upon different colonial logics – Catholic notions of normative sexual behavior and the pathologizing notion of incorrigible criminality – but the rest regarded crimes against the colonial government in support of autonomous Indigenous polities. One way of viewing these latter cases, in particular the severity of punishment wielded, is to consider them treasonous crimes against the colonial government as opposed to crimes against individuals. This, combined with the channeling of Indigenous captives into colonial systems of authority via penal deportation, suggests that banishment was not only a means to control imperial subjects but an effort at exerting colonial sovereignty by punishing individuals associated with rival polities. Yet, the exertion of sovereignty via interminable penal deportation was limited to Indigenous rivals, as records from penal establishments and colonial judicial institutions do not indicate the same treatment for prisoners taken in conflicts with European rivals. While suspicion toward foreigners, namely Portuguese subjects, motivated numerous cases of banishment, those instances tended to result in outward banishment from a settlement or jurisdiction rather than banishment to a penal destination.Footnote73

Differences between Indigenous captives and other presidiarios are also apparent when considering spiritual and cultural demands and experiences. Whereas nearly all presidiarios self-identified as Catholic when interrogated during their criminal trials and when called upon as witnesses, Lincompani and other captives from the Pampas region were baptized years after arriving to Malvinas, suggesting resistance or reticence until that point. Drawing upon lessons from scholarship on the trans-Atlantic slave trade also allows for speculation regarding Lincompani’s and other captives’ understanding of their predicament.Footnote74 Much like with captives from Africa forced onto slave ships, the multiweek maritime journey aboard a brigantine to Malvinas and subsequent disappearance of the coastline might have confronted Lincompani not only with seasickness but with the geographical and spiritual disorientation of a person whose entire life and sociopolitical world revolved around inland spaces. Such disorientation would presumably have persisted among the scant resources of the island: provisions were made for administering Catholic sacraments, but he would likely have struggled to undertake his own spiritual practices when divorced from his homeland and deprived of its resources. Likewise, the longing to be reunited with his kin expressed in his petition to the viceroy might have been augmented by the scarce number of Indigenous companions on the island. His exile coincided with that of Valerio – they arrived together, were baptized at nearly the same time, and they were pardoned together – but it appears that it did not overlap with any other Pampa besides Manuel Lorenzo, and given the ambiguity of naming and ethnic labels it is unclear whether they were the same person or, if not, whether they would have shared any affinity. While Valerio almost always appeared alongside Lincompani in records from Malvinas, often with a simple “same in everything” annotation, Manuel Lorenzo generally did not.

In addition to the culturally situated meaning making that may have shaped Lincompani’s and other Indigenous captives’ understanding of their predicament, ethnicity appears to have at times marked divisions among presidiarios. On the evening of 9 April 1803, while in their quarters, a presidiario named José Fontán stabbed another named Pasqual Valladares, who died soon after. In a subsequent investigation, numerous presidiarios testified that the skirmish had begun when Valladares, a pardo from Montevideo, approached a stove where Fontán was drying his socks and snarled, “I curse the ungrateful [Tape Indians].” Fontán, ostensibly a Tape himself, reportedly replied, “are you talking to me, friend?” to which Valladares allegedly retorted, “I’m not talking to you but it would be the same if I were” and approached Fontán. By the time the other presidiarios restrained them, Fontán had already inflicted Valladares with a mortal wound.Footnote75 Fontán’s confession presented a slightly different version of events. Aside from claiming that Valladares had threatened him earlier in the day while he was corralling livestock and that the stabbing occurred in self-defense with Valladares’s knife, he reported a different exchange of words. According to Fontán, Valladares had said, “these Indians are worth nothing but as women here” to which he replied, “I don’t come here to be a woman but to pay for my crime.”Footnote76 The invocation of Tape, an ethnic label often used synonymously with Guarani, and femininity as insults among presidiarios points to an economy of masculine honor mediated by one’s perceived ethnicity. To be a presidiario was to be dishonored, and the restoration of one’s calidad depended upon the performance of honorable behavior via manual labor associated with plebeian masculinity, namely the tending to livestock. It is unclear whether Valladares’s insults derived from a broader assumption among presidiarios of Indigenous captives’ dishonor or femininity, yet such divisions would mark an additional challenge for Fontán, Lincompani, and others.Footnote77

This individualization and alienation render Lincompani’s and other Pampas captives’ subsequent actions on Malvinas altogether remarkable. While Lincompani's role as a political leader or intermediary in the pampas might suggest that he was able to speak Spanish, the cultural competency needed to survive as a presidiario was likely more elusive. It appears that he and others took years to figure out how to navigate the scant resources available to presidiarios. While barely registering in the island’s records for almost a decade, they were baptized and made numerous petitions for royal clemency all within a three- or four-year span. One such petition, drafted with other presidiarios in his final year on the island, indicates that they received a quart of wine per day to manage the exhaustion of ranch work (fatigas de estanciero) and that when supplies ran short their rations were withheld. In the petition, he and others solicited that the government’s debt be repaid in money or in clothing, and the island’s military governor recommended payment in specie and in print money.Footnote78 What accounts for this sudden proclivity toward drafting petitions written in the genre of a supplicating subject? Perhaps Lincompani and the others ingratiated themselves to this particular commanding officer, thus enabling their petitions to be recorded and passed along to the viceroy, or perhaps they had to develop the requisite linguistic and legal knowledge to frame a petition. In the same manner, the collaborative nature of the petition for clemency and the recognition of a shared experience among presidiarios sentenced to life point to the forging of bonds over time. Rather than “social death,” their adaptation, resilience, and newly formed ties indicate the active making of social worlds amid dislocation from their home communities, the pernicious conditions of their banishment, and the crisis of oblivion.Footnote79

Whatever the case, the intermediate years between Lincompani’s arrival to Malvinas and his petition for release were shaped by quotidian violence. Few records from Malvinas point to the spectacular violence associated with other contexts of unfreedom, but the longevity of his banishment and the perpetual requirement that he labor despite his advanced age were nonetheless abnormal, debilitating, and traumatic. His crippled state was not an aberration but a predictable outcome given the circumstances of his punishment. Lincompani was not the only one who suffered in this way, as Pedro Pablo Suárez, who was serving a life sentence for having purportedly spied for Indigenous enemies, was found moribund on the beach outside Puerto de la Soledad and reportedly claimed that he had been run over by an oxcart in a nearby marsh.Footnote80 Other presidiarios ended up in the island’s hospital, some of whom died there, due to scurvy, syphilis, asthma, poor mental health, and general ailments (achaques), conditions that point to poor diet, hard labor, and overall lack of care.Footnote81

Even the selection of Malvinas as a destination placed undue burden on presidiarios. It was one of several regional penal destinations for convicts and captives, but its location far off the coast made it a uniquely isolated and particularly pernicious site of punishment in the minds of contemporaries. The intemperate climate and whipping winds received frequent mention in presidiarios’ petitions for transfer, as they cited the weather conditions as debilitating or, at the very least, preventing their recoveries.Footnote82 The island’s military commanders made similar complaints, noting as well storms that blew the roofs off of their buildings, rat infestations, and an overall scarcity of firewood.Footnote83 For their part, colonial officials on the mainland wielded banishment to Malvinas as an especially severe punishment that could rehabilitate one’s calidad, yet they occasionally conceded the deleterious effects of residing there.Footnote84 Neither Lincompani nor the other Indigenous captives sent to Malvinas were afforded the possibility of transfer, at least not until they learned the legal culture of petitions, pardons, and clemency. It was not until he supplicated to Spanish colonial sovereignty that his suffering became visible.

Conclusion

Perhaps Lincompani’s injury could have been avoided, as the viceroy in Buenos Aires had issued him a pardon around the same time as his fall. The precise reason for the pardon is somewhat ambiguous. A register of presidiarios in Malvinas noted that the viceroy had afforded clemency to Lincompani and two other presidiarios in 1791 “because they were invalids.” Yet, Lincompani was excluded from the list of presidiarios who would return to the mainland in 1792, leading the viceroy to issue another order for his freedom that year. This second order included Lincompani’s longtime companion, Valerio, who was not listed in the original pardon and who had reportedly died sometime in 1791.Footnote85 The viceroy explained that the colonial government had been investigating the cases of presidiarios who had not had juridical proceedings and that the commanding officer of Buenos Aires’s southern frontier was able to provide clarifying information. Lincompani was to be remitted to, and remain in, Montevideo. This second order did not take effect either, since the rotation of military commanders had led to confusion over who exactly was offered pardon, so the viceroy inquired about the delay and issued a third and a fourth order the following year.Footnote86 Two years after his fall and initial pardon, and fourteen years after first setting foot on Malvinas, Lincompani appears to have returned to the mainland, as Malvinas’s commander confirmed his embarkment in October 1793 and the viceroy documented his arrival in December. Both documents named him “Manuel Lorenzo” while citing the 1792 order to release “Lorenzo Licompani.” He was reportedly released, though records do not indicate where or what happened to him thereafter.Footnote87

Although exile in Malvinas comprised only a portion of Lincompani’s life, it cannot be untethered from a broader context of colonial exertions of land possession and sovereignty over autonomous Indigenous people. Rather than serving as a postlude to narratives of interethnic diplomacy and exchange in borderlands, penal deportation was integral to efforts to create and expand spaces of colonial law, and carceral spaces constituted sites of individualization and subjugation. Bringing together archival collections commonly treated in isolation reveals connections between distinct borderlands, as captives or purported criminals from one site were transformed into unfree settlers in another. A focus on captives’ experiences of forced migration to presidios allows for a deeper understanding of colonial efforts at racialization, ethnification, and Indianization beyond traditional sites of study, such as missions, cities, or Indigenous towns. The content of case files from Malvinas also lends to a deeper understanding of Indigenous agency, as captives built ties with others on the island to survive and to make sense of their predicament. Regardless of its value for analysis, Lincompani’s life matters, and while the stitching together of documentary fragments produces an ambiguous narrative, it challenges the archival erasure resulting from his deportation.

The content and structure of archives from penal destinations like Malvinas place certain constraints on this line of inquiry. Punishment and pain generated paper trails, but speculation is required when considering the quotidian nature of colonial violence or captives’ actions and experiences beyond suffering. Likewise, the bifurcation of captives according to perceived gender and age – adult men were sent to presidios and women and children were sent to urban centers or to missions – creates challenges to considering their experiences within a collective framework. Furthermore, Puerto de la Soledad was one of a handful of presidios located on island archipelagos far from continental coastlines and without local populations, making consideration of other sites and regions necessary. In southeastern South America, Indigenous captives were also commonly sent to Montevideo, a colonial city with an attached presidio, and throughout the Americas, the precise sites of penal deportation shaped the experiences of and opportunities afforded to captives.

Both the Malvinas Islands and the practices developed during the late eighteenth century remain deeply intertwined with interethnic relations in the region. Although Spain abandoned the archipelago in the early nineteenth century, Charrúas who appear to have been deported from Uruguay participated in an uprising against the British government on the islands in 1834, while the Argentine government sent at least one hundred Mapuches, Qom, Wichís, and Mocovíes to war against Great Britain over the islands in 1982.Footnote88 During Argentina’s invasion of Indigenous lands during the second half of the nineteenth century, thousands of captives were sent to Martín García, Carmen de Patagones, and other sites, where families were separated according to gender and age. The government subsequently conscripted men into the military while forcing women and children into domestic servitude with elite families in Buenos Aires and elsewhere, apart from their kin. Meanwhile, Argentina banished purported criminals from urban centers to penal establishments like Ushuaia, firmly in Indigenous lands.Footnote89 Indigenous people throughout Argentina and Uruguay continue to struggle for recognition and to access and control their lands, while Indigenous immigrants face myriad modes of social exclusion. These events and conditions were all born out of colonial logics regarding land possession, sovereignty, and Indigeneity. As deportation has come to signify forced migration across the borders of nation-states, it is necessary to remember that deportation to borderlands was integral to their invention and to the territorialized notions of sovereignty and inclusion that shape the practice today.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Pablo Álvarez Cabello, Claudio Barrientos Barría, Cristián Castro García, Jessica Delgado, Ana Díaz Burgos, Karen Graubart, Denisa Jashari, Carina Lucaioli, Juan Carlos Medel, Jaime Pensado, Paul Ramírez, Ana Sánchez Ramírez, and Sylvia Sellers-García for their comments on drafts of this article. I am grateful for the suggestions provided by the article’s anonymous reviewers and by the editors of Atlantic Studies. Research for this article was supported by the American Council of Learned Societies; the University of California, Santa Cruz’s Institute for Social Transformation and Committee on Research; and the University of Notre Dame’s Kellogg Institute for International Studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeffrey Erbig

Jeffrey Erbig is Associate Professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He is the author of Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America (UNC Press, 2020), which received honorable mention for the Alfred B. Thomas Book Award of the Southeastern Council of Latin American Studies in 2021. This work has been translated into Spanish as Entre caciques y cartógrafos: La construcción de un límite interimperial en la Sudamérica del siglo XVIII (Prometeo, 2022). Erbig’s research on borderlands studies, the history of cartography, historical geography, natural history, historical memory, and forced migrations has been published in such venues as the Hispanic American Historical Review, Ethnohistory, History Compass, and Boletín Americanista. His current research addresses histories of penal deportation in South America.

Notes

1 Archivo General de la Nación, Argentina (hereafter AGNA), IX, 16-9-8 [1481], Poblacion de la Soledad de Malvinas, 1791-08-n.d; AGNA, IX, 16-9-7 [1480], Montevideo, 1788-11-03; AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Islas Malvinas, 1792-09-07.

2 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Malvinas, 1792-02-26.

3 When considered on a global scale, upper estimates reach 28 million, with another 5.6 million additional people facing penal impressment. Anderson, “Introduction,” 1–2.

4 Examples of these earlier studies can be found in Chambouleyron, “Recrutamento e degredo na Amazônia,” 74–75. See also: Viotti da Costa, “Primeiros povoadores do Brasil,” 6–7, 15, 22. Works from the past half century that explicitly highlight colonial utilitarian logics and labor demands include: Hardy, “The Transportation of Convicts to Colonial Louisiana,” 207–208; Pike, Penal Servitude in Early Modern Spain, xiii, 49, 152; Coates, Convicts and Orphans, 107–119; Herzog, Upholding Justice, 35–36, 41; Toma, “A pena de degredo,” 67, 69–70, 71; Mehl, Forced Migrations in the Spanish Pacific World, 154, 192; Mawson, “Convicts or Conquistadores?” 102; De Vito, “The Spanish Empire, 1500–1898,” 67; Stoler, “Epilogue – In Carceral Motion,” 372; Coates, Convict Labor in the Portuguese, 2–3, 16, 26. Edith Ziegler has charted both tendencies in scholarship on convict transportation to mainland North America. Ziegler, Harlots, Hussies, and Poor Unfortunate, 5–7.

5 Rebagliati, “¿Custodia, castigo o corrección?” 39, 49, 54; Mehl, Forced Migrations in the Spanish Pacific World, 172–173, 210–211.

6 Monteiro, Negros da terra; Brooks, Captives & Cousins; Lucaioli and Latini, “Fronteras permeables”; Miles, The Dawn of Detroit; Levin Rojo and Radding, The Oxford Handbook of Borderlands in the Iberian World; Valenzuela Márquez, América en diásporas.

7 Ethridge and Shuck-Hall, Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone; Gallay, Indian Slavery in Colonial America; Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance, 9; Reséndez, The Other Slavery, 5, 324; Bialuschewski and Fisher, “New Directions,” 2. Nancy Van Deusen estimates that at least 650,000 Indigenous captives were forced to relocate to foreign lands rather than within a specific jurisdiction. Van Deusen, Global Indios, 2, 231n5.

8 This trend is particularly acute in studies of southeastern South America: Crivelli, “Malones ¿Saqueo o estrategia?,” 17–18; Hux, Caciques Puelches Pampas y Serranos, 38; Levaggi, “Tratados entre la Corona y los indios,” 714, 716–719; Alioto, Indios y ganado en la frontera, 68; Taruselli, “Alianzas y traiciones en la pampa,” 377–378; Lucaioli, Abipones en las fronteras, 284, 294; Alemano, “La prisión de Toroñan,” 32; Nacuzzi, “El 'indio Flamenco',” 47.

9 Erbig and Latini, “Across Archival Limits,” 254–259.

10 Van Deusen, “Holograms of the Voiceless.”

11 “Memoria de Juan José de Vértiz,” 149; Crivelli Montero, “Malones ¿Saqueo o estrategia?” 17–18; Hux, Caciques Puelches Pampas y Serranos, 38; Roulet, “Mujeres, rehenes y secretarios,” 309.

12 Tolderías were kin-based communities of several dozen to hundreds of inhabitants and mobile centers of authority in the countryside. Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 24.

13 Hernández, “Diario de la expedicion,” 35–60. Hux suggests that it was Lincompani’s father, Lincon, who led the tolderías in the expedition, yet Lincon and Lincompani may have been the same person. Hux, Caciques Puelches Pampas y Serranos, 36–38.

14 “Memoria de Juan José de Vértiz,” 149. See also: Museo Mitre, AE, C8, No. 6, fn. 6.

15 “Memoria de Juan José de Vértiz,” 150.

16 AGNA, IX, 25-3-13 [2203], El Pardo, 1781-03-14.

17 “Memoria de Juan José de Vértiz,” 151.

18 Levaggi, “Tratados entre la Corona y los indios,” 716.

19 Coates, “Portuguese Empire”; De Vito, “The Spanish Empire, 1500–1898,” 68–73.

20 Cáceres Menéndez and Patch, “'Gente de Mal Vivir,” 367–371; Souza Torres, “Exclusão e incorporação,” 148; Mawson, “Unruly Plebeians and the Forzado System,” 716–717; Mehl, Forced Migrations in the Spanish Pacific World, 24–25, 277–278; Coates, “Portuguese Empire.”

21 Cordero Fernández, “Destierro a la isla de Juan Fernández”; De Vito, “The Spanish Empire, 1500–1898,” 73–77; Gomes Lessa, Exílios meridionais.

22 Conrad, The Apache Diaspora, 141–168; Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 137–146, 161–162; Kagan, “Penal Servitude in New Spain,” 122; Dubois, A Colony of Citizens, 296–297; Bryant, Rivers of Gold, Lives of Bondage, 30; Araujo, “Black Purgatory,” 575, 579–580; Jones, “Enslaved and Convicted”; Brown, Tacky's Revolt, 105, 198, 209–213.

23 Poska, Gendered Crossings, 135–170; Punta, Córdoba borbónica, 219–224.

24 Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 12–38.

25 Lynch, Spanish Colonial Administration, 62–89.

26 Similar administrative complexities existed in the Andes. Herzog, Upholding Justice, 42–58; Alzate García et al., “Domains”.

27 See, for example: Marín Tello, La importancia de los presidios; Pike, Penal Servitude in Early Modern Spain, 134–147; Benton, A Search for Sovereignty, 176–187.

28 AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], Isla de la Soledad de Malvinas, 1805-03-27, 1806-03-06, 1808-08-14; AGNA, IX, 10-10-2 [842], Ysla de Fernando Poo, 1779-12-08. Convict flows generally followed the territorial limits of a specific jurisdiction, but viceroys had the ability to banish someone to other parts of Spain’s global empire. De Vito, “The Spanish Empire, 1500–1898,” 73–77. Fernando Poo was part of the jurisdictional umbrella of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata following its 1778 cession from Portugal to Spain, largely due to its potential as a slave-trading hub, while the Philippine Islands were part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, seated in Mexico City. Borucki, “The Slave Trade to the Río de la Plata,” 82.

29 Rebagliati, “¿Custodia, castigo o corrección?” 43–44.

30 See, for example: Archivo General de la Provincia de Santa Fe (hereafter AGPSF), Actas de cabildo de 1707-12-30, 1709-10-19, 1737-04-13, 1789-03-30.

31 AGNA, IX, 16-6-2 [1459], 16-6-3 [1460], 16-6-4 [1461], 16-9-1 [1474], 16-9-2 [1475], 16-9-3 [1476], 16-9-4 [1477], 16-9-5 [1478], 16-9-6 [1479], 16-9-7 [1480], 16-9-8 [1481], 16-9-9 [1482], 16-9-10 [1483], 16-9-11 [1484], 17-1-1 [1485], and 17-1-3 [1487].

32 Rebagliati, “¿Custodia, castigo o corrección?” 49–50.

33 AGPSF, Actas de cabildo de 1789-03-30, 1790-04-19. If following broader colonial trends, this targeting of migrants dovetailed with increasingly racialized policing in the late eighteenth century. Sellers-García, “Walking While Indian, Walking While Black.”

34 AGNA, IX, 8-10-1 [639], fs. 270–272; Lastarria, Documentos para la historia del Virreinato, 1:5.

35 Lipsett-Rivera, The Origins of Macho, 79–107.

36 Nacuzzi, “Los cacicazgos duales,” 139–140.

37 For examples from the pampas, see: Pinto Rodríguez, “Producción e intercambio”; Mandrini and Ortelli, “Repensando viejos problemas”; Boccara, Los vencedores, 339–340.

38 Molina, “Ladrones, vagos y perjudiciales,” 26–27; Alemano, “Los Blandengues de la Frontera”; Fradkin, “Las milicias de caballería”.

39 Aguirre, “Cambiando de perspectiva”; Bracco and López Mazz, Charrúas, pampas y serranos, chanáes, 7–9; Roulet, “Mujeres, rehenes y secretarios,” 309; Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 137–162; Lepore, The Name of War, 170; Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance; Cramaussel, “Forced Transfer of Indians,” 186–187; Lucaioli and Latini, “Fronteras permeables,” 126; Lipman, The Saltwater Frontier, 203–243; Conrad, The Apache Diaspora, 141–168.

40 AGNA, IX. 16-6-2 [1459], Isla de Martín García, (1767-04-25, 1767-05-02, 1767-09-18, 1767-11-18, 1768-12-11, & 1769-02-18); Rebagliati, “¿Custodia, castigo o corrección?” 39; Aguirre, “Cambiando de perspectiva,” 6–7.

41 Peña, “Don Francisco de Céspedes,” 187.

42 Aguirre, “Cambiando de perspectiva”; Sarmiento, “Indias urbanas en Buenos Aires,” 156–198; Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 137, 145–146.

43 Archivo General de Indias, Buenos Aires, 235, fs. 31v, 50v–51, 70v, 89v, 108, 130–30v, 150v, 172, 191, 214v, 349v, 259v, 296, 320–320v, 345v, 371v–72, 385v, 405v–406, 429v.

44 AGNA, IX, 4-3-1 [202], Santo Domingo Soriano, 1746-07-29, 1746-10-16; Bulkeley and Cummins, A Voyage to the South Seas, 201–208.

45 AGNA, IX, 4-3-1 [202], Las Vívoras, 1750-09-15, 1750-12-07; Santo Domingo Soriano, 1750-10-21.

46 Diccionario de autoridades, v. 3; Bluteau, Vocabulário Português e Latino, 3:400.

47 Archivo General de la Nación, Uruguay (hereafter AGNU), Manuscritos Originales Relativos a la Historia del Uruguay, 50-1-3, carpeta 10, carpeta 10, no. 1, f. 6; Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 68, 119–122, 138–146.

48 Barros Arana, Historia general de Chile, 6:237–238.

49 Mandrini, “Transformations”; Punta, Córdoba y la construcción de sus fronteras, 164–165, 169.

50 Nacuzzi has shown that Flamenco was not a cacique in the traditional sense of representing a single group with a single ethnic identity, but instead shared authority with different caciques over time and acted an intermediary between numerous communities identified by distinct ethnic labels. Nacuzzi, “El ‘indio Flamenco,’” 40, 46–57.

51 AGNA, IX, 16-9-3 [1476], Malvinas, 1771-09-30; AGNA, IX, 16-9-4 [1477], Malvinas, 1778-08-05 & 1778-10-15; Taruselli, “Alianzas y traiciones en la pampa,” 372–378. The commander of the expedition requested that Flamenco be allowed to remain in the countryside thereafter. AGNA, IX, 1-6-2 [29], Luján, 1784-06-11, fs. 703–704, cited in Crivelli Montero, “Pactando con el enemigo,” 22.

52 Taruselli, “Alianzas y traiciones en la pampa,” 376–377. Flamenco, Antuco, Concher, Juancho, Felipe, and Felipe arrived to Malvinas in September of 1771. AGNA, IX, 16-9-3 [1476], Malvinas, 1771-09-30.

53 AGNU, ex-AGA, caja 37, carpeta 6, n. 6, Buenos Aires, 1774-09-22; Alemano, “La prisión de Toroñan,” 32, Alioto, Indios y ganado en la frontera, 68.

54 Aguirre, “Cambiando de perspectiva,” 6–7.

55 Lucaioli, Abipones en las fronteras, 284.

56 AGNA, IX, 16-9-7 [1480], Islas Malvinas, 1789-04-12; Buenos Aires, 1789-07-23 & 1791-11-22.

57 Hernández, “Diario de la expedicion,” 35; Barbará, Manual ó vocabulario de la lengua pampa, 102.

58 AGNA, IX, 16-9-5 [1478], (Buenos Aires, 1780-01-26; Islas Malvinas, 1780-03-04 and 1781-02-27; Puerto de la Soledad de Malvinas, 1782-04-06); AGNA, IX, 16-9-7 [1480], (Montevideo, 1788-11-03; Islas Malvinas, 1789-04-12 and 1789-07-23); AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], (Buenos Aires, 1792-11-22 and 1793-06-11; Islas Malvinas, 1792-09-07).

59 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Buenos Aires, 1793-03-13.

60 Archivo General de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Juzgado del Crimen, 34-1-10-34/1.

61 AGNA, IX, 16-9-8 [1481], Buenos Aires, 1791-11-22.

62 AGNA, IX, 16-9-8 [1481], Islas Malvinas, 1791-05-15; AGNA, IX, 16-9-5 [1478], Islas Malvinas, 1781-02-27; Puerto de la Soledad de Malvinas, 1782-04-06.

63 Nacuzzi, “Los cacicazgos duales,” 137, 140; Levaggi, “Tratados entre la Corona y los indios,” 717–719; AGNU, AGA, caja 147, carpeta 3, doc. 11 (Buenos Aires, 1786-03-02).

64 AGNA, IX, 1-5-6 [27], 1792-11-12, cited in Levaggi, “Tratados entre la corona y los indios,” 714n35.

65 Hux, Caciques Puelches Pampas y Serranos, 38; Nacuzzi, “Los cacicazgos duales,” 139–140; Roulet, “Mujeres, rehenes y secretarios,” 309; Weber, Bárbaros, 326n81, 343n131; Alioto, Indios y ganado en la frontera, 68, Alemano, “La prisión de Toroñan,” 47.

66 Hux, Caciques Puelches Pampas y Serranos, 38.

67 Nacuzzi, Identidades impuestas; Giudicelli, Luchas de clasificación; Erbig and Latini, “Across Archival Limits,” 259–264.

68 Pike, Penal Servitude in Early Modern Spain, 20–25; Benton, A Search for Sovereignty, 181–182.

69 AGNA, IX, 16-9-5 [1478], Buenos Aires, 1780-01-26.

70 AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], proceso formado contra José Fontan, Islas Malvinas, 1803-04-09, fs. 4-9v; AGNA, IX, 16-9-1 [1474], causa contra Domingo Pereyra, Islas Malvinas, 1768-03-21, fs. 1-23v.

71 AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], Soledad de Malvinas, 1803-04-09.

72 AGNA, IX, 16-9-5 [1478], Puerto de la Soledad de Malvinas, 1782-04-06 and 1782-03-20; Montevideo, 1781-12-20; AGNA, IX, 16-9-10 [1483], Colonia de Malvinas, 1796-03-15; AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Buenos Aires, 1792-02-16; AGNA, IX, 16-9-8 [1481], Islas Malvinas, 1791-05-15.

73 AGPSF, actas de cabildo de 1651-09-27 and 1766-06-09; AGNA, IX, 8-10-1 [639], fs. 114, 116–117, 138–139, 152, 178.

74 On archives and Atlantic slavery, see: Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery; Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”; Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives.

75 AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], 4v–6, 7–9v.

76 AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], 11v–13v.

77 On the relationship between race, insults, and masculine honor, see: Johnson, Workshop of Revolution, 68–75; Lipsett-Rivera, The Origins of Macho, 143–171.

78 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Islas Malvinas, 1792-08-31; Soledad de Malvinas, 1792-09-07.

79 As argued by Vincent Brown for studies of slavery, “the agency of the weak and the power of the strong” were not antithetical. Political action was not limited to resistance to colonial institutions and included the creation of social worlds. Brown, Social Death and Political Life, esp. 1232–1233, 1244.

80 AGNA, IX, 16-9-10 [1483], Soledad de Malvinas, 1797-07-21.

81 AGNA, IX, 16-9-3 [1476], Malvinas, 1771-06-19; AGNA, IX, 17-1-3 [1487], Soledad de Malvinas, 1803-10-30; AGNA, IX, 16-9-7 [1480], Montevideo, 1788-11-03; AGNA, IX, 16-9-10 [1483], Malvinas, 1795-08-01.

82 AGNA, IX, 16-9-10 [1483], Colonia de Malvinas, 1797-02-24; AGNA, IX, 32-3-9 [2788], Buenos Aires, 1784-02-26, fs. 64–65.

83 AGNA, IX, 16-9-2 [1475], Islas Malvinas, 1769-02-10; AGNA, IX, 16-9-3 [1476], Malvinas, 1771-06-19.

84 AGNA, IX, 16-9-8 [1481], Buenos Aires, 1791-08-25; AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Buenos Aires, 1792-02-21; Islas Malvinas, 1793-01-20.

85 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Islas Malvinas, 1792-03-01 and 1792-08-31; Buenos Aires, 1792-11-22.

86 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Buenos Aires, 1793-03-13 and 1793-06-11.

87 AGNA, IX, 16-9-9 [1482], Islas Malvinas, 1793-10-10; Buenos Aires, 1793-12-27.

88 Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met, 138, 204n2; Chico, Los Qom de Chaco en la guerra de Malvinas.

89 Papazian and Nagy, “Prácticas de disciplinamiento indígena”; Kerr, Sex, Skulls, and Citizens, 30–37; Edwards, A Carceral Ecology.

Bibliography

- Diccionario de autoridades, vol. 3. Madrid: Real Academia Española, 1732.

- Aguirre, Susana. “Cambiando de perspectiva: cautivos en el interior de la frontera.” Mundo Agrario. Revista de estudios rurales 7, no. 13 (2006): 1–16.

- Alemano, María Eugenia. “La prisión de Toroñan: Conflicto, poder y “araucanización” en la frontera pampeana (1770–1780).” Revista TEFROS 13, no. 2 (2015): 27–55.

- Alemano, María Eugenia. “Los Blandengues de la Frontera de Buenos Aires y los dilemas de la defensa del Imperio (1752–1806).” Fronteras de la Historia 22, no. 2 (2017): 44–74. doi: 10.22380/20274688.104

- Alioto, Sebastián L. Indios y ganado en la frontera: La ruta del río Negro (1750–1830). Rosario: Prohistoria ediciones, 2011.

- Alzate García, Adrián, John Ermer, Morgan Gray, Lisa Howe, Gloria Lopera Mena, Judith Mansilla, Bianca Premo, Gracia Solis, Victor Uribe, and Sheyla Aguilar de Santana. “Domains: The Colonial Spanish America Digital Jurisdictions Project.” https://arcg.is/0mXDH9.

- Anderson, Clare. “Introduction: A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies.” In A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies, edited by Clare Anderson, 1–35. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

- Araujo, Ana Lucia. “Black Purgatory: Enslaved Women’s Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.” Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 4 (2015): 568–585. doi: 10.1080/0144039X.2014.1001159

- Barbará, Federico. Manual ó vocabulario de la lengua pampa y del estilo familiar. Buenos Aires: Imprenta y Librería de Mayo de C. Casavalle, 1879.

- Barros Arana, Diego. Historia jeneral de Chile, vol. 6. Santiago de Chile: Rafael Jovier, 1884.

- Benton, Lauren A. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Bialuschewski, Arne, and Linford D. Fisher. “New Directions in the History of Native American Slave Studies.” Ethnohistory 64, no. 1 (2017): 1–17. doi: 10.1215/00141801-3688327

- Bluteau, Raphael. Vocabulário Português e Latino, vol. 3. Coimbra: Colégio das Artes da Companhia de Jesus, 1728.

- Boccara, Guillaume. Los vencedores: Historia del pueblo mapuche en la época colonial. Translated by Diego Milos. San Pedro de Atacama: Línea Editorial IIAM, 2007.

- Borucki, Alex. “The Slave Trade to the Río de la Plata, 1777–1812: Trans-Imperial Networks and Atlantic Warfare.” Colonial Latin American Review 20, no. 1 (April 2011): 81–107. doi: 10.1080/10609164.2011.552550

- Bracco, Diego, and José M. López Mazz. Charrúas, pampas y serranos, chanáes y guaraníes: La insurrección del año 1686. Montevideo: Linardi y Risso, 2006.

- Brooks, James. Captives & Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Brown, Vincent. “Social Death and Political Life in the Study of Slavery.” The American Historical Review 114, no. 5 (2009): 1231–1249. doi: 10.1086/ahr.114.5.1231

- Brown, Vincent. Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Bryant, Sherwin. Rivers of Gold, Lives of Bondage: Governing through Slavery in Colonial Quito. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

- Bulkeley, John, and John Cummins. A Voyage to the South Seas, in the Years 1740–1. London: Printed for Jacob Robinson, 1743.

- Cáceres Menéndez, Beatriz, and Robert W. Patch. “‘Gente de Mal Vivir: Families and Incorribible Sons in New Spain, 1721–1729.” Revista de Indias 66, no. 237 (2006): 363–392.

- Chambouleyron, Rafael. “Recrutamento e degredo na Amazônia seiscentista.” In História militar da Amazônia: guerra e sociedade (séculos XVII–XIX), edited by Alírio Cardoso, Carlos Augusto Bastos, and Shirley Maria Silva Nogueira, 73–84. Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2015.

- Chico, Juan. Los Qom de Chaco en la guerra de Malvinas. Una herida abierta. Na Qom na LChaco so halaataxac ye Malvinas. Nque’emaxa saimiguiñe. Resistencia: Cospel, 2016.

- Coates, Timothy J. “Portuguese Empire: Convicts and their Labour.” Accessed July 10, 2019. http://convictvoyages.org/expert-essays/convicts-and-their-labour-in-portugal-and-the-portuguese-empire.

- Coates, Timothy J. Convicts and Orphans: Forced and State-Sponsored Colonizers in the Portuguese Empire 1550–1755. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

- Coates, Timothy J. Convict Labor in the Portuguese Empire, 1740–1932. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Conrad, Paul. The Apache Diaspora: Four Centuries of Displacement and Survival. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

- Cordero Fernández, Macarena. “Destierro a la isla de Juan Fernández a fines del siglo XVIII: Civilización, corrección y exclusión social.” In América en diásporas: Esclavitudes y migraciones forzadas en Chile y otras regiones americanas (siglos XVI–XIX), edited by Jaime Valenzuela Márquez, 439–467. Santiago: RIL editores, 2017.

- Cramaussel, Chantal. “Forced Transfer of Indians in Nueva Vizcaya and Sinaloa: A Hispanic Method of Colonization.” In Contested Spaces of Early America, edited by Juliana Barr and Edward Countryman, 184–207. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

- Crivelli Montero, Eduardo A. “Malones ¿Saqueo o estrategia? El objetivo de las invasiones de 1780 y 1783 a la frontera de Buenos Aires.” Todo es Historia, no. 283 (1991): 6–32.

- Crivelli Montero, Eduardo A. “Pactando con el enemigo: La doble frontera de Buenos Aires con las tribus hostiles en el período colonial.” Revista TEFROS 11, no. 1–2 (2013): 1–58.

- De Vito, Christian G. “The Spanish Empire, 1500–1898.” In A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies, edited by Clare Anderson, 65–95. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

- Dubois, Laurent. A Colony of Citizens: Revolution & Slave Emancipation in the French Caribbean, 1787–1804. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Edwards, Ryan C. A Carceral Ecology: Ushuaia and the History of Landscape and Punishment in Argentina. Oakland: University of California Press, 2021.

- Erbig, Jeffrey Alan, Jr. Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

- Erbig, Jeffrey Alan, Jr. and Sergio Latini. “Across Archival Limits: Colonial Records, Changing Ethnonyms, and Geographies of Knowledge.” Ethnohistory 66, no. 2 (2019): 249–273. doi: 10.1215/00141801-7298765

- Ethridge, Robbie, and Sheri-Marie Shuck-Hall, eds. Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- Fradkin, Raúl O. “Las milicias de caballería de Buenos Aires, 1752–1805.” Fronteras de la Historia 19, no. 1 (2014): 124–150. doi: 10.22380/2027468834