ABSTRACT

Suicide and violence are a major concern in prisons, and it has been suggested that alexithymia may be associated with these behaviours. Alexithymia can be defined as the inability to identify and describe emotions. This study aimed to explore staff’s understanding and attitudes about identifying and discussing emotions in prisoner suicide and violence. Twenty prison staff across departments were interviewed about their understanding of how emotional difficulties contribute towards prisoner suicide and violence. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. Analysis revealed five main themes and nine subthemes. Staff felt that prisoners struggled to identify, understand and communicate their emotions which led to intense and sudden outbursts of emotion. In turn, prisoners responded to these outbursts using two main maladaptive coping strategies; drug and alcohol use and harming self or others. This process was placed in a broader context of both upbringing and the prison environment. These findings therefore suggest that a change to prison regime and culture is crucial to encouraging prisoners to overcome difficulties with identifying, understanding and communicating emotions which, in turn, could help to reduce rates of suicide and violence in prison.

Introduction

Suicide and violence represent a major concern in prisons with 87 suicides, 55,598 incidents of self-injurious behaviours and 34,223 assault incidents in England and Wales in 2018 (Ministry of Justice, Citation2019). Previous research on harm in prison has tended to focus on either harm to self (self-harm and suicide) or harm to others (violence and aggression), though more recently it has been recognised that it is important to focus on the duality of these risks (Slade, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2017). Slade (Citation2018) has therefore advocated for further research to be conducted into the exploration of ‘dual harm’ in prisoners – where an individual engages in both harm to self and harm to others. This argument is supported by previous research that showed a high proportion of prisoners who harm themselves will also harm others (Slade, Citation2018). Theoretical explanations for this co-occurrence include the notion that both destructive behaviours are caused by the same risk factors, with some suggesting that self-harm occurs when aggression ‘turns inwards’ (Plutchik et al., Citation1989).

It has been suggested that emotion regulation difficulties may play a role in both suicide (Rajappa et al., Citation2012; Zlotnick et al., Citation1997) and violence (Davidson et al., Citation2000; Roberton et al., Citation2012). Specifically, one form of emotion dysregulation which has been hypothesised as relating to both suicide and violence is alexithymia (Hemming, Haddock et al., Citation2019; Hemming, Taylor et al., Citation2019). Alexithymia can be defined as an inability to identify or express emotions and consists of three main factors; difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty describing feelings and a focus on externally oriented thinking patterns (Sifneos, Citation1973). Related constructs include emotional intelligence which has been described as a way to quantify emotion regulation (Onur et al., Citation2013), and concerns an individual’s ability to understand, process and manage emotions as well as their ability to integrate affects (Salovey & Mayer, Citation1990). Individuals experiencing alexithymia are found at the lowest end of the emotional intelligence scale (Mayer & Salovey, Citation1993).

Previous research has found that alexithymia is more closely related to suicidal thoughts than suicidal behaviours, and that the sub-factors of difficulty identifying and describing feelings are most closely related with suicidal thoughts and behaviours Hemming, Taylor et al. Citation2019. Further, previous research has found a relationship between alexithymia and violence in a range of populations including adult offenders (Roberton et al., Citation2014), people experiencing substance dependence (Evren et al., Citation2015; Payer et al., Citation2011) and males with antisocial personality disorder (Ates et al., Citation2009). Again, the sub-factors of difficulty identifying and communicating feelings have been found to most closely relate with violence.

Prison staff have a key role to play in the prevention of suicidal and violent behaviour amongst prisoners. Despite this, previous research has shown that prison staff tend to harbour negative attitudes towards those who harm themselves or others. For instance, prison officers have tended to view self-harm as an attention-seeking strategy or as a means of manipulation, whilst viewing suicide as a product of the prisoner’s internal world, rather than a product of prison life (Kenning et al., Citation2010; Liebling, Citation2002; Pannell et al., Citation2003; Snow, Citation1997). Further, general hospital staff reported feeling frustration, anger and irritation in response to verbal and physical aggression displayed by patients (Zernike & Sharpe, Citation1998) and it appears that healthcare staff are ambivalent on whether aggression is caused by internal factors such as mental state and psychopathology or environmental factors such as ward turmoil and staff shortages (Jansen et al., Citation2005).

It has been argued that prison staff have previously been neglected in research on suicide and violence, despite them having a wealth of experience and reflection to contribute (Liebling, Citation2002). To date, there has been no research which explores prison staff’s understanding and attitudes towards the role of identifying and discussing emotions in prisoners at risk of suicide and violence. This is important as previous research has suggested that such difficulties may contribute towards thoughts and behaviours related to harming self or others. This study therefore sought to explore the views and opinions of a range of prison professionals on the role of identifying and discussing emotions with at-risk prisoners.

Method

This study received ethical approval from North East – York Research Ethics Committee on 22 May 2017, (Reference: 17/NE/0132) and from HMPPS on 27 September 2017 (2017–268). Approval was also sought from the governor of each prison site included in the study.

Sampling

Purposive sampling was used to identify 20 staff who have experience of working with suicidal or violent prisoners across four prisons in the North West of England. Maximum variation sampling was used to recruit staff who varied across key dimensions including time spent working within prisons and job role. Staff were recruited through dissemination of posters via e-mail, physical copies being placed around the prison establishment and staff self-selecting to take part in the study. All staff provided written consent and were interviewed at a time and place of their choosing.

Data collection

A flexible, open-ended topic guide was used to explore staff’s understanding of alexithymia, how they felt this related to prisoner’s suicidal or violent thoughts and behaviours and the way in which prison staff identify and discuss emotions. Since few participants were familiar with the term alexithymia, a brief definition of alexithymia was given at the beginning of all interviews:

“Sometimes people struggle to understand and describe their feelings and emotions. This is known as ‘alexithymia’. People with alexithymia may struggle to communicate their feelings to other people and might also have difficulties using their imagination.”

Prompts were prepared to explore how staff felt these issues related to suicide and violence, though in most instances, these issues arose naturally during discussion of the concept of alexithymia. All interviews were conducted by LH on a one-to-one basis either face to face in a location within the prison (n = 9) or over the telephone (n = 11) to allow maximum flexibility (Sturges & Hanrahan, Citation2004). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and identifying information was removed from transcripts. Interviews lasted on average 49 minutes (range 28–89 minutes). Data collection and analysis occurred in parallel, using a constant comparative technique to generate new data based on incoming data (Glaser, Citation1965). Data collection ceased upon reaching data saturation whereby no new relevant ideas emerged (Dey, Citation2012).

Analysis

The data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis to identify common themes and discrepancies across the views of participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Initial familiarisation with the data was achieved by reading and re-reading transcripts, followed by line by line coding using NVivo version 11 software. Data were analysed by LH, with a selection of transcripts being coded by DP, JS and GH to provide differing perspectives on the data.

Results

The sample included staff from a range of professions including seven HMPPS-employed uniformed staff, five NHS-employed healthcare staff, six staff from programmes, recreation, education and chaplaincy and one governor. On average, staff had worked in prisons for 14 years (range 0.5–28 years) and in the past year had worked with between zero and 50+ suicidal and/or violent prisoners. The average age of staff was 43 years, 70% of participants were male and 95% of participants were White British.

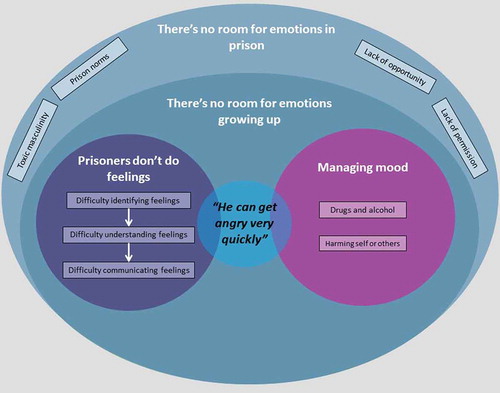

Five main themes were identified. illustrates the relationship between each of the five themes.

Prisoners don’t do feelings

This theme outlined the difficulties that staff perceived prisoners to have in relation to alexithymia. There were three subthemes; difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty understanding feelings and difficulty communicating feelings. The subthemes were inter-related, in that, a difficulty with identifying feelings led prisoners to subsequently experience a difficulty understanding feelings and both of these things combined caused a difficulty with communicating feelings. The majority of staff agreed that these issues were prevalent amongst prisoners with most prisoners experiencing a difficulty with identifying or understanding or communicating emotions, or a combination of all three.

Difficulty identifying feelings

Staff described that prisoners often had difficulty identifying their own and others’ emotions, and that often prisoners could get emotions confused. Furthermore, they described prisoners as experiencing a small range of emotions or flattened affect, and this was often attributed to the belief that prisoners were unable to identify emotions apart from anger.

“You know I mean they can do kind of happy, sad, just about. Beyond that everything’s anger.” (STA02)

“It’s just that everything is anger, so then they know that they end up being angry, but they don’t actually understand the emotions that they move through to get to the anger.” (STA04)

Difficulty understanding feelings

In relation to the perceived difficulties that prisoners faced identifying their feelings, staff also felt that it was common for prisoners not to understand their feelings. Whilst related, the two concepts differed in that staff perceived it was possible for prisoners to identify a shift in emotions without understanding what this emotion was or entailed.

“I mean they might say, ‘I’m depressed’, but even when you sort of say, ‘well what does depressed mean?’, they find it quite hard to say what that means.” (STA02)

Difficulty communicating feelings

It was commonly perceived that prisoners had difficulties with communicating their feelings. Staff stated that the language used by prisoners to describe their feelings tended to be fairly basic, often mimicked clinical language and frequently centred on anger or frustration. Staff also felt that prisoners were better at communicating facts than feelings.

“It tends to be more that they can state the facts rather than emotions. So, they can sit in front of me and quite openly tell me quite horrible details about their childhood, but if you tried to ask them how they feel now, looking back at it and things like that, it suddenly gets a bit stilted then and it’s not as easy for them to say than it is to actually just tell me the gory details, as such.” (STA10)

Staff felt that prisoners often communicated their emotions using non-verbal or visual methods, and that prisoners were better at communicating their emotions after they had happened, as opposed to whilst they were experiencing them.

“Some of the guys work better off the colour. So, they’ll just say … ‘well I feel black’, or ‘I feel angry’ and some of them draw pictures.” (STA04)

As well as a cognitive inability to communicate feelings, staff also spoke about both prisoners and staff being reluctant to communicate their emotions. Reluctancy to discuss emotions was closely related to who the individual could trust. For prisoners, this meant that they were often reluctant to communicate emotions to peers, even the listeners (a peer support prisoner trained to provide confidential emotional support), due to fears of appearing weak. Staff also spoke about a general lack of trust between prisoners and staff due to staff representing ‘the system’ that incarcerated them in the first place.

“Um and trust as well. I think being in prison environments … it’s a very ‘I’m grassing’ environment. So, if they say anything then they’re a grass. So, I think they sort of get used to not saying anything about anything.” (STA05)

Finally, staff had mixed views on who prisoners might be most likely to communicate their emotions with. Whilst some felt that they would be more likely to speak to staff, due to not wanting to appear weak to their peers, others felt they would be more likely to speak to peers, due to not wanting to be labelled as a ‘grass’ for talking to staff. Further, staff felt that there were particular staff that prisoners would be more likely to communicate their feelings to; these tended to be female staff and non-uniformed roles such as nurses, civilian staff, education, workshops and recreation staff. Staff also felt that there were particular peers that prisoners would be more likely to communicate their emotions with; these tended to be people who prisoners may feel they’re more able to trust, such as listeners or close family or friends in prison. Staff also felt that there were particular types of prisoners who would be more likely to communicate their feelings to others, such as older prisoners and prisoners considered as ‘vulnerable prisoners’.

“They’d rather go to staff than go to another prisoner. They’re very defensive if they find out that other prisoners know about their emotions or their problems.” (STA16)

“I think the barrier of the white shirt is, in a lot of cases, almost insurmountable for them to talk to. Nurses, I think less so.” (STA20)

‘He can get angry very quickly’

As a result of the difficulties outlined in the previous theme 'prisoners don't do feelings', staff perceived that prisoners often experienced intense, sudden emotions. This was felt to be due to the inability of prisoners to identify the build-up of distressing feelings. This build-up of emotions was considered to be compounded by the difficulties faced by prisoners in communicating their emotions.

“He would get full of emotions, so like a bottle of pop. And then it would get closer and closer to the top and then it would just get shook up. And then when you take the cap off, boom.” (STA04)

“And he can go from one extreme to the other, can get very angry very quickly, get very upset very quickly, and sort of swing very dramatically.” (STA08)

Managing mood

As a result of the intense, sudden emotions outlined in theme two 'he can get angry very quickly', staff felt that prisoners often responded to these emotions by using maladaptive ways to manage their mood. This theme had two subthemes; drug and alcohol use and harming self or others. Simultaneously, staff felt that drugs and alcohol use and harming self or others may also contribute to the experience of intense, sudden emotions.

Drug and alcohol use

Staff noted that prisoners often used drugs and alcohol to mask or hide their emotions, and felt that substances were often used as an emotional avoidance strategy. Staff also acknowledged that the consumption of drugs and alcohol could itself contribute to subsequent intense and sudden emotions.

“One of the reasons they may use substances is because of the way they feel and an inability to cope. And that can often be because they can’t express themselves in an acceptable way to family or friends or professionals. You know, they struggle to explain how they’re feeling.” (STA08)

Harming self or others

Staff felt that the difficulties experienced by prisoners in identifying and communicating their emotions could lead to them trying to hurt themselves or others. This was recognised as occurring frequently in prison and was seen to be intuitive to the majority of participants. However, some felt that there was a more intuitive link between violence and self-harm and emotional difficulties than with suicide. This was due to violence and self-harm being seen as closely related with feelings of anger or frustration, which in turn, were feelings that were assumed to be closely related to the emotional difficulties experienced by prisoners. Further, staff felt that violence and self-harm were more impulsive acts which were fuelled by anger, whereas suicide was perceived as a more carefully thought out response to emotions such as sadness and regret.

“A lot of the coping is just not to talk about it or not to show weakness by talking about it. So then, to me, violence and self-harm would be the understandable, no not understandable, but I could see why that would happen. What else are you gonna do?” (STA04)

Despite some staff feeling that there was a less intuitive link between alexithymia and suicide, conversely, others noted that suicidal prisoners may struggle to communicate their emotions. Staff perceived a dichotomy between prisoners who harmed themselves or others for ‘manipulation’ purposes and prisoners who ‘genuinely’ struggled with harming self or others. It was felt that the former of these groups had no difficulties in identifying and communicating their emotions, as this was perceived as necessary in order to attain their defined goal. The latter of these prisoner groups however, tended to struggle to talk about their emotions, and were therefore at an even greater risk of harming self or others.

“Um I think people who are seriously suicidal don’t [communicate their emotions]. I think people who are self-harming do because that is a cry for help.” (STA11)

Staff also felt that the difficulties faced by prisoners with identifying and communicating their feelings could prevent them from seeking help and may therefore leave prisoners more vulnerable to harming self or others.

“I guess that if you’re very distressed and you’re not able to formulate your feelings and thoughts in terms of emotion, you might struggle to find solutions for those and it’s harder to get help for those difficulties so you might find that you’re considering suicide as an option.” (STA02)

Finally, some staff felt that harm to self or others might be an effective way to open up a conversation about emotions that prisoners would otherwise struggle to do. It was perceived that violent or self-harm behaviour served to make unobservable distressing emotions into a tangible and observable experience that could be discussed with others. Staff felt that outward signs of harm to self or others were therefore a clue that staff should pick up on that prisoners might be struggling to understand and communicate their feelings.

“I wonder if you don’t know how you’re feeling, you just know something’s wrong, and you self-harm, then you do have something to focus on, you do have an experience you understand. There might be something about that. There’s something physical, there’s something tangible that they can actually identify and think about rather than, this, ‘well something’s wrong but I don’t know what it is.’” (STA02)

There’s no room for emotions growing up

Staff felt that the difficulties outlined in ‘prisoners don’t do feelings’ stemmed from personal histories, which meant that prisoners had often received little to no education on how to identify and express their feelings and had not grown up in households where this was the norm.

“A lot of them are from deprived backgrounds, a lot of them aren’t particularly well educated and I think that certainly has an impact on how they’ve been brought up and how they’ve been told to express their feelings.” (STA18)

Staff also saw harming self or others as an automatic, learnt response to distressing emotions which may have stemmed from childhood. In combination with the lack of education about emotions, it was felt that prisoners therefore coped with this lack of understanding of emotions by learning to hurt themselves or others.

“A lot of people that are in custody have had fractured upbringings … so actually they’ve never been taught this emotion is anger, and this has come from here, and you need to manage it in this way. So, they don’t know how, so they just learn how to do that themselves, whether that is by harming themselves or by acting out in quite an aggressive way.” (STA13)

There’s no room for emotions in prison

In addition to personal histories contributing towards the difficulties outlined in ‘prisoners don’t do feelings’, staff also felt that the current environment of the prison contributed to these difficulties alongside the likelihood of drug and alcohol use and harming self or others. As illustrated in , the context of being in the prison environment was inherently related to all other themes and subthemes. This environment was perceived to affect both prisoners and prison staff alike which led to inhibited communication of emotions. There were four main subthemes in this theme; prison norms, lack of opportunity, lack of permission and toxic masculinity.

Prison norms

Staff strongly felt that it was the norm not to talk about emotions whilst in prison. Talking about emotions was perceived as ‘weak’ and so prisoners avoided doing so due to wanting to show bravado and fit in. Furthermore, it was perceived that the expression of certain emotions, such as anger, were more acceptable or more easily understood in a prison, alongside behaviours which were seen as more acceptable in the prison environment, such as violence and self-harm.

“Well I mean culturally, you don’t talk about your emotions. You don’t sit with your cellmate and talk about how you’re feeling quite wistful today.” (STA02)

“Yeah it’s just like an unofficial prisoner code of conduct. You don’t talk about your weaknesses.” (STA16)

Staff spoke about the same sets of norms existing for prison staff which meant that they, too, struggled to communicate their feelings within the prison environment.

“The same principles apply to staff. You couldn’t have staff bawling in the corner somewhere, nobody’s got time for that.” (STA15)

Lack of opportunity

Staff spoke about prisoners having a lack of opportunity to communicate their feelings due to prison regime and staff shortages.

“It’s also the environment. Just purely because there is no outlet, they don’t have that kind of … as I said, we’re so short staffed the kind of one on one time you get with people is very limited.” (STA10)

The physical prison environment was also perceived to contribute to the lack of opportunity to communicate emotions due to an absence of safe and confidential spaces.

“Somebody tapping on your cell at tea time, ‘are you alright?’, you’re sat there with your cellmate, ‘are you suicidal?’, ‘er no, I’m alright boss’. What do you expect them to actually say?” (STA20)

Lack of permission

Participants felt that staff often didn’t ask about emotions in a meaningful way due to staff not feeling confident or prepared to do this. Instead, such questioning tended to be centred around processes of risk management such as the Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT) process, which staff agreed wasn’t always conducive to open and meaningful conversations about feelings. Participants also felt that staff struggled to ask other staff about their emotions meaningfully.

“I mean I think we do spend a lot of time asking people how they feel but probably not in a way that really gets the answer. So for example, in ACCT reviews or in segregation reviews, I think superficially we look like we’re interested in the person’s emotions but we probably don’t have a very sophisticated approach to dealing with that.” (STA09)

Staff also perceived that both prisoners and staff often didn’t give themselves permission to connect with their feelings. This was often seen as a protective response which helped prisoners and staff alike to cope with prison life.

“I’ve had a lot of suicides in my career, a dead body’s never affected me … Don’t get me wrong, I’m not made of steel, I mean if it were my own family, different kettle of fish. But to me, it’s just a prisoner. I can somehow detach my emotions from that.” (STA17)

Toxic masculinity

As already alluded to, staff spoke about prisoners not wanting to communicate feelings due to wanting to show bravado and not wanting to appear weak. It was perceived that these difficulties with communicating feelings might exist in males everywhere, akin to the notion of toxic masculinity, defined as aspects of hegemonic masculinity that foster domination of others and are socially destructive (Kupers, Citation2005). Despite this, staff recognised that the interplay between toxic masculine values and the expectations of the prison environment culminated in prisoners struggling to communicate their feelings with staff and others.

“You know, as men, we’re not really encouraged … to talk about things like that … There’s lots and lots of pressures in the community that mean that men don’t particularly want to talk about, or feel that they can’t talk about their mental health … because it brings a stigma and brings unwanted attention that can make you feel vulnerable. But I think that when you come into a prison environment, that gets multiplied. Simply by the fact that you’re living with hundred lads … that are all trying to survive, all trying to fit in. And that brings an extra level of scrutiny … I think these problems exist everywhere but I think when you come into a prison it’s just heightened because of the nature of the environment you find yourself in.” (STA08)

Staff, primarily male staff, again, felt that this macho culture affected the way in which prison staff, too, would communicate their feelings. This in turn had an impact on how they worked with and were perceived by prisoners who were suicidal and/or violent.

“Definitely when I was an officer, there was that kind of roughty toughty, ‘nothing’s going to affect me’ … So, when it came to the self-harm and the suicide and people disclosing information, are you really coming across as the guy they can talk to confidentially? How empathetic actually are you to that person’s needs?” (STA20)

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study found that prison staff acknowledged and identified the role that emotional difficulties may play in prisoner suicide and violence. Specifically, staff outlined a process whereby prisoners struggle to identify, understand and communicate their feelings which can lead to intense, sudden outbursts of emotion. In turn, these outbursts are often managed using strategies such as drug and alcohol use or harming self or others. Staff also placed this process in a wider context of both a historical upbringing and a present circumstance of residing in prison, which made prisoners privy to the pervasive standards of toxic masculinity, stressing that this process is inherently linked to both contexts.

Comparisons with wider literature

There has been a paucity of literature to date which has investigated staff views on the role of emotions in prisoner suicide and violence. Despite this, the current findings resonate with previous research which has more broadly explored emotion regulation in prisoners. Whilst there appears to be little research which supports the notion that prisoners struggle to identify and understand their emotions, several other studies have found that prisoners struggle to communicate their emotions whilst in prison (Crewe et al., Citation2014; Evans & Wallace, Citation2008; Kupers, Citation2005; Laws & Crewe, Citation2016). Other researchers have described how for some prisoners, ‘the language of emotional expression was somewhat alien’ and that ‘there is a softer, gentler inner world best kept off the landing’ (Evans & Wallace, Citation2008)(pp. 500, 488). Others have echoed the sentiment that prisoners may be hesitant to discuss their emotions with staff due to concerns about confidentiality, and may also struggle to communicate emotions with other prisoners due to concerns for their own safety (Kupers, Citation2005). Despite this, and in keeping with findings presented here, previous studies have also reported prisoners tend to limit disclosure of their emotions to within specific groups of trusted peers and staff, physical locations such as in the chapel or via particular mediums for example, over the telephone or using letters (Laws & Crewe, Citation2016). Crewe et al. (Citation2014) noted that prisoners can sometimes display visible emotional ‘eruptions’ such as smashing up cells, displaying anger on the wing or breaking down in public after difficult phone calls. The present findings suggest that staff may have a good insight into the difficulties that prisoners face in communicating their emotions and the potential outcomes that may subsequently arise, such as sudden and intense bursts of emotion.

The findings in the present study regarding managing mood echo that of previous studies. For instance, the self-medication hypothesis postulates that individuals may turn to using drugs and alcohol as a way to regulate strong affects which one perceives to be unmanageable (Khantzian, Citation1997; Lane & Schwartz, Citation1987; Michael, Citation1990). Whilst this does not seem to have been formally tested in a male prisoner population, Greer (Citation2002) notes in her qualitative study with female prisoners that several participants described having used drugs and alcohol prior to beginning their sentence to diminish or blur their awareness of feelings. Furthermore, former research findings confirm the notion that prisoners may engage in harming self or others as a way of managing mood (Crewe et al., Citation2014; Laws & Crewe, Citation2016). Kupers and Toch (Citation1999) suggested that difficulties with communicating emotions may also lead to prisoners wanting to hurt themselves, stating that male prisoners tend to underreport their emotional problems until it reaches a point of suicidal crisis . The present findings reported mixed perspectives on whether or not suicidal prisoners experienced difficulties with communicating their emotions, with some participants viewing suicide as a somewhat rational act stemming from a clear understanding of feelings, whilst others suggested that emotional difficulties, particularly with communicating feelings, could itself contribute to feeling suicidal. Whilst previous research has quantitatively found a relationship between alexithymia and suicide (Hemming, Taylor et al., Citation2019), this complexity highlights the need for further qualitative research which examines the nature of this relationship. Broader than this, previous findings support the idea that staff dichotomise harm to self or others into ‘genuine’ and ‘non-genuine’ and that those who are ‘genuinely’ struggling are perceived as having more complex emotional needs (Kenning et al., Citation2010; Liebling, Citation2002; Snow, Citation1997). Despite this, previous findings have shown that particular groups of staff may be more inclined to see harm to self or others as a function of emotional difficulties, such as officers from ethnic minority groups, as well as healthcare and governing staff (Kenning et al., Citation2010).

Evans and Wallace (Evans & Wallace, Citation2008) provided support for the notion that male prisoners often do not experience emotional socialisation in early childhood and that this may impact the way in which they understand and communicate their emotions later in life. Qualitative interviews with male prisoners revealed that they had learnt about violence from a young age, and their early life experiences had taught them that this was intrinsically linked with negative emotions. Furthermore, Greer (Citation2002) found that female prisoners often attributed their emotional numbness to dysfunctional childhoods which again supports the present finding that emotional difficulties in prison may stem from emotionally deprived childhoods.

A wealth of prior research has echoed findings that it is the norm not to discuss emotions in prison, particularly emotions which may render an individual as ‘weak’ or ‘vulnerable’ (Crawley, Citation2004; Crewe, Citation2012, Citation2014; Crewe et al., Citation2014; Evans & Wallace, Citation2008; Jewkes, Citation2005; Karp, Citation2010; Kupers, Citation2005; Laws & Crewe, Citation2016; De Viggiani, Citation2012). Laws and Crewe (Citation2016) summarised the experiences of their participants neatly by stating: ‘Prison environment and prisoner culture may induce or shape particular forms of regulation, such as the suppression of emotion. The open expression of “weaker” emotions (such as fear and sadness) was admonished by the prisoners in this research who said it could lead to exploitation at the hands of exploitative and ruthless prisoner groups.’ (p. 543). Whilst the present study found that anger tended to be a more acceptable emotion to express in prison, previous studies were contradictory on this finding, with some echoing this (Crawley, Citation2004) whilst others finding that prisoners did not feel anger was a safe emotion to show in prison, due to fear of being reprimanded by staff (Crewe et al., Citation2014; Laws & Crewe, Citation2016).

There is limited support for the finding that being in prison limits the opportunities that prisoners have to discuss their emotions. For instance, Laws and Crewe (Laws & Crewe, Citation2016) recognise that the ability of prisoners to control emotion may be contingent on temporal and spatial factors over which they have little control, though they also found that prisoners tried to gain some control over this for instance, by only crying alone in their cell. Greer (Citation2002) echoed this sentiment stating that female prisoners often don’t have a choice on whether they express their emotions in private due to living with hundreds or thousands of other inmates. Further, participants in Laws and Crewe’s (Citation2016) study stated that they would only share intimate feelings with loved ones via phone calls, visitations and letter writing, though these were notoriously difficult to access due to limited use of phones and the associated financial costs.

The present study found that prisoners don’t give themselves permission to connect with their feelings whilst in the prison environment. This finding resonates with previous research which has found that prisoners felt the need to block out their emotions for the duration of their sentence in order to avoid becoming overwhelmed by feelings of weakness and distress (Crewe et al., Citation2014; Laws & Crewe, Citation2016).

Finally, the present study found that prison staff perceived an interplay between prison values and toxic masculinity values which culminated in an increased difficulty with emotions. This is reflective of previous research findings which suggest that traits of toxic masculinity tend to be overrepresented in male prisons (Gerzon, Citation1982; Kupers, Citation2005). Further to this, previous research has recognised that whilst toxic masculinity traits exist everywhere, residing in prison may heighten this due to more traditional avenues of achieving status being unavailable to men, therefore making them prone to amplifying their ‘toughness’ (Laws & Crewe, Citation2016). As Kupers (Kupers, Citation2005) states; ‘Gender is not entirely a matter of social structure or personal psychology; it is formed at the interface of the two. The toxic masculinity that bursts out at angry moments in prison cannot be blamed entirely on any particular set of individual characteristics of prisoners, nor is the emergent toxic masculinity formed in a vacuum.’ (p. 719). Here, Kupers (Citation2005) suggests that both prisoners and prison staff’s actions are impacted by the notion of toxic masculinity which dominates much of prison culture. Kupers (Citation2005) also recognises practical restrictions imposed on prisoners which makes hegemonic masculinity traits difficult to avoid; for instance, the fact that prisoners have nowhere to turn to if they want to walk away from a confrontation.

It has previously been found that staff tend to view suicide as a product of the internal world (Kenning et al., Citation2010; Liebling, Citation2002; Pannell et al., Citation2003) and violence as a mixture of internal and external environments (Jansen et al., Citation2005). The present study found that staff acknowledged the interplay between internal difficulties (such as difficulties with identifying, understanding and expressing emotions) and external pressures (such as prison norms, lack of opportunity, lack of permission and toxic masculinity). Indeed, staff acknowledged that there were prisoners who engaged in harm to self or others, who did not appear to experience difficulties identifying, understanding or communicating emotions – such as those who engaged in harm to self or others for ‘manipulation’ purposes. This may suggest that those who do struggle to identify, understand and communicate their emotions may have experienced such a difficulty before entering the prison environment, as is alluded to in theme 4 ‘there’s no room for emotions growing up’. This theory is supported by literature which finds a relationship between alexithymia and suicide, self-harm and violence in the community (Fossati et al., Citation2009; Hemming, Taylor et al. Citation2019 ; Norman & Borrill, Citation2015). This recognition of the interplay between internal and external factors reflects previous literature which has found, for instance, that self-harm is related to intrapersonal difficulties such as alexithymia, depression and lower resilience as well as external factors such as bullying (Garisch & Wilson, Citation2015).

This study found that the prison environment was perceived by staff to have had an impact upon the emotional difficulties experienced by prisoners. This environmental impact is not limited to the prisoners alone though, with staff participants also recognising a similar impact upon their own emotional expression and language. Specifically, staff reported prison norms and a macho culture prevented them from discussing their emotions openly with colleagues or prisoners, and impacted the way in which they worked with, and were viewed by, suicidal and violent prisoners. Further, staff also spoke about ‘disconnecting’ from their emotions whilst on the job, which staff members viewed as an important protective measure for their own wellbeing. Previous literature supports these findings, suggesting that correctional officers’ levels of emotional intelligence affects decision making (Basu, Citation2016) and also that detaching from emotions may be a necessary step for staff in order to succeed in the workplace (Crawley, Citation2004). Importantly, the difficulties that participants in this study reported with emotional expression and regulation, is likely to have had an influence on the expression of their views of prisoners, and thus the data presented here. Future research should aim to explore the issues of emotional difficulties, and links with suicidal and violent behaviours, with prisoners directly, which may help to minimise any third party effects. Furthermore, future research should aim to explore differences in perceptions of the prison environment that may exist between male and female prison staff.

Strengths and limitations

The study provides the first qualitative exploration of prison staff attitudes and understanding towards the role of identifying and communicating emotions in suicide and violence. Despite this, it is limited in that all staff were employed to work in a prison in the North West of England and the majority of staff were White British. It may therefore be that others’ experiences and opinions may differ to the results presented here. Furthermore, whilst the present study includes the views and experiences of staff from a range of roles within the prison, due to small numbers of each profession, it was not possible to compare the experiences and attitudes between groups. Future research may benefit from such comparisons.

Clinical and research recommendations

Several recommendations for clinical practice and training arise from the present study. The findings indicate that the prison environment is integral to the process which links together difficulties with emotions and maladaptive coping strategies such as drug and alcohol use and harming self or others. As such, this indicates a need for changes with the prison system and regime which could give prisoners opportunity and permission to understand and discuss their emotions. One specific recommendation to overcome the lack of opportunity to discuss emotions is to ensure that prisoners have access to a private space to discuss their emotions on a one-to-one basis with a trusted staff member. This is especially pertinent following the recent introduction of the role of ‘personal officers’, who may be able to provide this individual support to prisoners. Secondly, staff should be trained in how to ask about prisoners’ emotions meaningfully so that they feel confident to do this in the prison environment.

More broadly than this, a cultural shift within prisons is required to overcome the more systemic issues such as prison norms and toxic masculinity, which prevent prisoners and prison staff from discussing their emotions. A number of community campaigns have recently focussed on encouraging men to talk about their feelings. For example, campaigns such as ‘Rammy Men’, ‘Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM)’ and the ‘Heads Up’ campaign backed by The Football Association all aim to highlight how important it is for men to discuss their feelings, particularly as males are at a higher risk of both suicide and violence than females. The findings from this study suggest that a similar educational campaign may be beneficial in a prison environment, to encourage the open and honest communication of emotions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank the staff working in the safer custody departments of the recruitment prisons who were instrumental in data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ates, M. A., Algul, A., Gulsun, M., Gecici, O., Ozdemir, B., Basoglu, C., et (2009). The relationship between alexithymia, aggression and psychopathy in young adult males with antisocial personality disorder/Antisosyal kisilik bozuklugu olan genc erkeklerde aleksitimi, saldirganlik ve psikopati iliskisi. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 46(4), 135–140.

- Basu, R. (2016). The role of emotional intelligence in the decision making process of correctional officers, of the West Bengal correctional services. Journal of Services Research, 16(2), 67–78.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Crawley, E. M. (2004). Emotion and performance: Prison officers and the presentation of self in prisons. Punishment & Society, 6(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474504046121

- Crewe, B. (2012). The prisoner society: Power, adaptation and social life in an English prison. OUP.

- Crewe, B. (2014). Not looking hard enough: Masculinity, emotion, and prison research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(4), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413515829

- Crewe, B., Warr, J., Bennett, P., & Smith, A. (2014). The emotional geography of prison life. Theoretical Criminology, 18(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480613497778

- Davidson, R. J., Putnam, K. M., & Larson, C. L. (2000). Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation–a possible prelude to violence. science, 289(5479), 591–594. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5479.591

- De Viggiani, N. (2012). Trying to be something you are not: Masculine performances within a prison setting. Men and Masculinities, 15(3), 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X12448464

- Dey, I. (2012). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry. Crane Library at the University of British Columbia.

- Evans, T., & Wallace, P. (2008). A prison within a prison? The masculinity narratives of male prisoners. Men and Masculinities, 10(4), 484–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06291903

- Evren, C., Cinar, O., Evren, B., Umut, G., Can, Y., & Bozkurt, M. (2015). Relationship between alexithymia and aggression in a sample of men with substance dependence. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(3), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.5455/bcp.20130408020445

- Fossati, A., Acquarini, E., Feeney, J. A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Giarolli, L. E., Franciosi, G., & Maffei, C. (2009). Alexithymia and attachment insecurities in impulsive aggression. Attachment & Human Development, 1(11), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730802625235

- Garisch, J. A., & Wilson, M. S. (2015). Prevalence, correlates and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6

- Gerzon, M. (1982). A choice of heroes: The changing faces of American manhood. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH).

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.2307/798843

- Greer, K. (2002). Walking an emotional tightrope: Managing emotions in a women’s prison. Symbolic Interaction, 25(1), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2002.25.1.117

- Hemming, L., Haddock, G., Shaw, J., & Pratt, D. (2019). Alexithymia and its associations with depression, suicidality and aggression: An overview of the literature. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00203

- Hemming, L., Taylor, P., Haddock, G., Shaw, J., & Pratt, D. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between alexithymia and suicide ideation and behaviour. Journal of Affective Disorders, 254, 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.013

- Jansen, G. J., Dassen, T. W., & Groot Jebbink, G. (2005). Staff attitudes towards aggression in health care: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00772.x

- Jewkes, Y. (2005). Men behind bars: “Doing” masculinity as an adaptation to imprisonment. Men and Masculinities, 8(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X03257452

- Justice, M. (2019). Safety in custody statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in prison custody to March 2019 assaults and self-harm to December 2018. Ministry of Justice. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/797074/safety-custody-bulletin-q4-2018.pdf

- Karp, D. R. (2010). Unlocking men, unmasking masculinities: Doing men’s work in prison. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 18(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1801.63

- Kenning, C., Cooper, J., Short, V., Shaw, J., Abel, K., & Chew‐Graham, C. (2010). Prison staff and women prisoner’s views on self‐harm; their implications for service delivery and development: A qualitative study. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20(4), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.777

- Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229709030550

- Kupers, T. A. (2005). Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 713–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20105

- Kupers, T. A., & Toch, H. (1999). Prison madness: The mental health crisis behind bars and what we must do about it. Jossey-Bass.

- Lane, R. D., & Schwartz, G. E. (1987). Levels of emotional awareness: A cognitive-developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(2), 133-143.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-18836-001

- Laws, B., & Crewe, B. (2016). Emotion regulation among male prisoners. Theoretical Criminology, 20(4), 529–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480615622532

- Liebling, A. (2002). Suicides in prison. Routledge.

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1993). The intelligece of emotional intelligence. Intelligence, 17(4), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2896(93)90010-3

- Michael, R. (1990). A preliminary investigation of alexithymia in men with psychoactive substance dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(9), 1228–1230.DOI: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.122

- Norman, H., & Borrill, J. (2015). The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia. Personality and Social Psychology, 56(4), 405–419.https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12217

- Onur, E., Alkin, T., Sheridan, M. J., & Wise, T. N. (2013). Alexithymia and emotional intelligence in patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly, 84(3), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-012-9246-y

- Pannell, J., Howells, K., & Day, A. (2003). Prison officer’s beliefs regarding self-harm in prisoners: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Forensic Psychology, 1(1), 103–110.http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30020623

- Payer, D. E., Lieberman, M. D., & London, E. D. (2011). Neural correlates of affect processing and aggression in methamphetamine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.154

- Plutchik, R., van Praag, H. M., & Conte, H. R. (1989). Correlates of suicide and violence risk: III. A two-stage model of countervailing forces. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90048-6

- Rajappa, K., Gallagher, M., & Miranda, R. (2012). Emotion dysregulation and vulnerability to suicidal ideation and attempts. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(6), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9419-2

- Roberton, T., Daffern, M., & Bucks, R. S. (2012). Emotion regulation and aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.006

- Roberton, T., Daffern, M., & Bucks, R. S. (2014). Maladaptive emotion regulation and aggression in adult offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(10), 933–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2014.893333

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

- Sifneos, P. E. (1973). The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 22(2–6), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000286529

- Slade, K. Dual harm: Working with those who harm both themselves and others. 2017.

- Slade, K. (2018). Dual harm: An exploration of the presence and characteristics for dual violence and self-harm behaviour in prison. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 8(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCP-03-2017-0017

- Slade, K. (2019). Dual harm: The importance of recognising the duality of self-harm and violence in forensic populations. SAGE Publications Sage.

- Snow, L. (1997). A pilot study of self-injury amongst women prisoners. Issues in Criminological & Legal Psychology, 28, 50-59.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-35817-006

- Sturges, J. E., & Hanrahan, K. J. (2004). Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research, 4(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104041110

- Zernike, W., & Sharpe, P. (1998). Patient aggression in a general hospital setting: Do nurses perceive it to be a problem? International Journal of Nursing Practice, 4(2), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172X.1998.00073.x

- Zlotnick, C., Donaldson, D., Spirito, A., & Pearlstein, T. (1997). Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(6), 793–798. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199706000-00016