ABSTRACT

Maternal incarceration can be a disruptive process for the entire family. Incarcerated mothers experience stigma and are often regarded both as criminals and mothers who willingly abandoned their children. There have been several studies examining the impact on the children of incarcerated parents. However, a synthesis of qualitative studies exploring the lived experience of these women is lacking. This systematic review seeks to provide a qualitative evidence synthesis of the literature. The following research question guided the review; what are the experiences and perceptions of being a mother in prison while separated from your children. Using the thematic synthesis method, data from 15 studies were analysed. Four analytical themes were found: ‘Barriers to Motherhood’, ‘Burden of Perceived Maternal Failure’, ‘Salvation through Motherhood’ and ‘A Better Future’. Motherhood was both the source of a perceived failing and offered redemption for the incarcerated women. As such, this review supports evidence that the mothering role should be encouraged and facilitated while these women are in prison.

Introduction

This systematic review synthesises the qualitative research exploring the experience of mothering from prison while separated from one’s child(ren). Female prisoners and incarcerated mothers’ difficulties were explored through the lens of maternal identity and the struggle to maintain their mothering role while imprisoned. Prior to introducing the current review, an overview of existing research in the area is discussed.

Background

The number of female prisoners is increasing worldwide (Baldwin, Citation2017). One report suggests women and girls in prisons has increased by approximately 60% since 2000 (Fair & Walmsley, 2022). Complete numbers for female prisoners are not available however a approximate number given in the World Female Imprisonment List (Fair & Walmsley, 2022) suggests that more than 740,000 females are held in penal institutions worldwide. The majority of female prisoners are mothers with at least one child (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Swavola et al., 2016). Research from 2012 stated that 66% of female prisoners in the UK were mothers to dependent children (Epstein, 2012). A 2015 report linking the UK’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Ministry of Justice data estimated that between 24%-31% of female offenders had dependent children (Ministry of Justice, 2015). However, they cautioned that this might be an underestimate. Maternal incarceration is detrimental to the family system, negatively impacting children (Epstein, 2012; Murray et al., 2012; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010). Children tend to live with their mothers prior to their incarceration rather than their fathers, further contributing to family disruption and distress (United Nations, 2014). While the majority of countries have some form of accommodation for mothers and their children to live together in prison, the logistics of this differ between jurisdictions and opportunities for this tend to be restricted to mothers and infants. As a result, most incarcerated mothers are separated from their children when they enter prison (Crewe, Citation2020). While incarceration may be a stressful time for all prisoners, the additional separation from their children can become the central difficulty and worry during mothers’ imprisonment (Enos, Citation2001; Page et al., Citation2021). The stresses and anxieties experienced by mothers were attributed to the separation from their children, as demonstrated during a qualitative study completed in a women’s prison in the United States (Forsyth, 2003). This finding is supported by quantitative research, which found that the stress women experience due to the limited contact with their children during imprisonment was related to increased anxiety, depression and somatisation (Houck & Loper, 2002).

Motherhood has historically been viewed as a developmental task with vast social and cultural implications and is considered by some as essential to female identity (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010). The maternal role is seen as unique; one is not just a parent or part of the child’s system but fulfilling a precise cultural and biological role (Stern, 1995). Furthermore, mothering is seen as both an identity and behaviour (A. Booth et al., Citation2018 in Stringer, Citation2020). Motherhood is loaded with societal expectations and can be viewed as something that is placed upon women in order for them to live up to a virtuous role (Enos, Citation2001). One’s ability to perform this role in a socially acceptable way increases a sense of belonging and competence (Parry, Citation2022). Maternal identity comprises a woman’s identification with the role and her belief around competence in fulfilling it (Mireault et al., 2002).

Developing a maternal identity is a process that is continually negotiated (Bibring et al., 1961). This process comes under significant strain when mothers are incarcerated. While physically separated from their children, female prisoners may attempt to maintain their mothering role and maternal identity, albeit indirectly (Lewin et al., Citation2018; Page et al., Citation2021). Their ability to directly perform the mothering role becomes compromised, and thus they strive to maintain their maternal identity in some form (Enos, Citation2001). Incarcerated mothers attempt to persevere their maternal identity by dissociating themselves from other incarcerated mothers (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Enos, Citation2001). Motherhood is often viewed through the dichotomous lens of good versus bad. In some accounts incarcerated mothers attempt to cast themselves as the ‘good mother’ to preserve their own maternal identity and dissociate themselves from the other perceived ‘bad’ incarcerated mothers. (Demeli, Citation2010; Enos, Citation2001).

Preservation of the mothering role

Previous research has shown that incarcerated mothers are eager to maintain their role as mothers (Greene et al., 2000). However, the practicalities of continuing the mothering role, such as the difficulties of children attending visits (Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019), the cost of telephone calls (N. Booth, Citation2020) and the decision of whether to tell children about their imprisonment (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018), impinge upon their ability to continue with their role. As such, a grieving process for the lost practical role of mothering may take place (Boudin, 1998). As mothers can no longer fulfil their roles in traditional ways, they attempt to find new ways to fulfil their role as the ‘good mother’, such as making financial sacrifices to afford the cost of telephone calls (Lockwood, 2013) and engaging in parenting classes (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; Pollock, 2003).

Mothers may experience a sense of guilt and shame over their choices and actions that led to their incarceration and subsequent separation from their children (Demeli, Citation2010; Boudin, 1998; Imber-Black, 2008; Masson, 2019). This shame is often internalised from the social stigma of being an incarcerated mother (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). Women who commit crimes, particularly mothers, fail to live up to the societal notion of being a woman and a mother (Keitner, 2002). Women’s crimes, especially violent crimes, shock society; in response, these women are labelled as extraordinary in order for us to collectively return to the imagined gendered status quo of crime (R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012). Imprisoned mothers are stigmatised and viewed as an incarnation of the societal image of a ‘bad mother’. These women are viewed as criminals, but they are also perceived as inadequate mothers (Enos, Citation2001) who have chosen to leave their children (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011).

Contrastingly, women cite their dependent children and their desire to provide for them as reasons behind their criminality (Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007). Furthermore, dependent children can act as a motivation for change for these women (Enos, Citation2001). Societal bias may sometimes be mirrored within the staff, who also may hold negative stereotypes of incarcerated women and mothers (Schram, 1999).

Current literature and objectives

While there is a growing body of qualitative literature exploring the experience of mothering in prison (Baldwin, Citation2017; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019), there is no known review systematically synthesising women’s experiences and perspectives. There are a small number of reviews in the broader area. For example, several reviews have examined the literature on prison parenting programmes (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012). An integrative review has examined perinatal outcomes for pregnant women in prison (Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019). Baldwin (Citation2017) systematically examined how mother-child separation within the UK is referred to across the literature base with respect to attachment theory. Contrastingly, Cooper-Sadlo et al. (Citation2019) reviewed literature exploring the experience of mothers whose children reside with them in prison. More closely linked to the current review was one undertaken to examine the impact of incarceration on parents in the United States; however, this was not completed systematically, and no synthesis of the data was performed. Furthermore, no search strategy was provided, and no quality assessment appeared to take place (Page et al., Citation2021). With this in mind, we propose a clear gap within the literature for a comprehensive qualitative evidence synthesis exploring mothers’ experiences of incarceration while separated from their children. There is a strong need to have a clear systematic synthesis of this information to incorporate these women’s voices within policy and practice recommendations. By incorporating these voices, policies, interventions and strategies may become more effective and foster the mother-child bond during this difficult time while also increasing the chances of successful re-entry for both women and their families (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).

The current review sought to synthesise qualitative evidence of the experience of mothers in prison who are separated from their children. The review was guided by the following question: What are women’s experiences and perceptions of being a mother in prison while separated from their children?

Methodology

The review utilised the ‘Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ)’ statement (Tong et al., 2012) to ensure comprehensive reporting. Preliminary searches were carried out to assess the viability of the review, and a protocol was registered on the Prospero website (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021289398).

Searching

A systematic search was conducted using online databases. The search strategy was informed by SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type; Cooke et al., 2012) and developed in consultation with an information specialist. This strategy was piloted and found to have sufficient sensitivity for retrieving articles relevant to the research question. Searches took place on the 12th of November, 2021. Six electronic databases, including two grey literature databases, were searched. A search strategy for each database is provided in . A combination of MESH/subject headings/thesaurus terms and keywords were utilised within each respective search engine. No limits on language or publication date were applied. The initial search yielded 1150 references (754 following de-duplication), which were imported into Endnote X9 file. The endnote file was subsequently uploaded to the Ryan software (https://rayyan.ai, 2021). In addition, the references of the final included studies were searched using a forward and backward strategy to identify additional, potentially relevant literature (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011).

Table 1. Search Syntax.

Screening

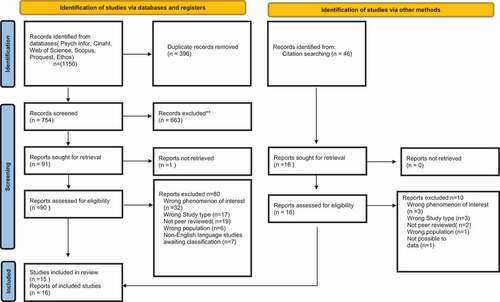

The lead author screened the title, keywords, and abstracts of all studies retrieved against the inclusion and exclusion criteria in . Twenty per cent of the retrieved title, abstract and keywords were screened independently by the second reviewer. In cases where the information required to determine if a study met the inclusion criteria was not evident in the title and abstract, the full text was screened. Where the lead author and second reviewer were not in agreement, the article was put forward for full-text screening. The lead author and the second reviewer independently screened all papers that met the criteria for full-text screening. The screening tool is provided in the appendices (Appendix A). Any conflicts or doubts regarding inclusion were discussed and resolved. provides more information on this process. While initially it was planned to include grey literature in the form of theses, hence the database searches on ProQuest and Ethos, after initial screening, it became clear that the inclusion of grey literature would be beyond the scope of this review due to the number of unpublished theses. Therefore, grey literature was subsequently excluded. As the review team did not have a second language, studies in languages other than English could not be included. These have been listed as ‘studies awaiting classification’ in to ensure transparency in the review process (Glenton et al., Citation2020). Where the same study, using the same sample and methods but was presented in different reports, these reports were collated so that each study (rather than each report) is the unit of interest (Glenton et al., Citation2020).

Figure 1. Prisma Flow chart illustrating selection of studies (Page et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria used for Screening.

Data extraction

Information regarding study details (author, publication year, setting), participants, design and methods were extracted from the studies selected for inclusion the program NVivo (software version 12 2019, QSR International Pty Ltd; Baldwin, Citation2017). The characteristics to be extracted were informed by Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) and Lewin et al. (Citation2018) guidelines. These guidelines suggest extracting a number of characteristics the relevant characteristics to this review from those suggestions were extracted. Additionally, first-order (participant quotes) and second-order (author) interpretations that reflected the review question were extracted from the abstract, results and discussion sections using NVivo software (software version 12 2019, QSR International Pty Ltd; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). The second reviewer independently extracted the data from 20% of the included studies (N. Booth, Citation2017). Their extraction was consistent with the lead author’s extraction.

Assessing the methodological limitations of included studies

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist was used to assess the methodological limitations and the quality of the included studies (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). The CASP checklist identifies issues to be considered when appraising a qualitative study, including its validity and if the results are of value locally (CASP,Citation2018). This tool was used to aid the interpretation of findings at later stages of the review. Studies were not excluded based on poor quality, as how a study is reported is not necessarily an indication of how the study was conducted (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2007). One-third of the studies were independently assessed using the CASP tool by members of the review team (GW & CH).

Thematic synthesis

Thematic synthesis methodology was chosen to synthesise the extracted data (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). This decision was guided by the RETREAT framework, which considers various criteria for selecting a synthesis method: the research question, epistemology, time/timescale, resources, expertise, audience, and purpose/type of data (A. Booth et al., Citation2018). Thematic synthesis involves the systematic coding of data and the generation of descriptive and analytical themes. It moves beyond solely describing qualitative studies to developing new explanations or interpretations across study findings.

The data were synthesised within NVivo directly from the included papers. The coding involved three steps: line-by-line coding, which incorporated free codes and axial coding. These codes were then grouped into descriptive themes and subsequentially developed into analytical themes. The descriptive themes stick closely to the data of the original papers, whereas the analytical themes move beyond the raw data and directly address the aims of the review (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Each stage was captured within NVivo, providing an audit trail. The analytical themes were broken down into sub-themes to reflect the core findings. The GRADE CERQual tool assessed confidence in the review findings (Lewin et al., Citation2018). This tool uses four components to evaluate confidence in the qualitative evidence synthesis findings: methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy of data, and relevance. An overall rating of confidence was then given to each finding.

Author reflexivity

In keeping with quality standards for rigour in qualitative research, the review authors, in particular the lead author, considered their views and opinions on incarcerated mothers and incarceration in general as possible influences on the decisions made in the design and conduct of the study and, in turn, on how the results of the study influenced those views and opinions. The lead author maintained the reflexive stance detailed below throughout the stages of the review process, from study selection to data synthesis. Progress was discussed regularly among the team and the lead author, with decisions being critically explored. The review team have backgrounds: in clinical psychology, nursing and health psychology. One team member has significant expertise in qualitative evidence synthesis, and the lead author regularly engaged with her regarding the process which ensured rigour when completing the review. The authors remained mindful of presuppositions and supported each other to minimise the risk of skewing the analysis or the interpretation of the findings. For example, initially the potential beneficial nature of prison for some women was being lost in the analysis however due to the reflective stance of the team this was highlighted and when we revisited the data with a more open mind the data which contributes to the fourth analytical theme was highlighted. The lead author, kept a reflexive journal throughout the review process to document and reflect on progress and decisions made. To minimise biases, interpretations of the data were repetitively questioned among the team. All team members were asked to verify that the findings reflected the supporting data accurately. The same process of awareness of personal biases was applied during the appraisal of confidence in the findings.

Results

Summary of included studies and participants

Fifteen studies were included in this review; one study was split across two papers meaning that there were 16 papers included. Studies involved 479 participants in total. Participants ranged from 18 to 63 years old; however, not all studies provided an age range. Six studies were based in the USA (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Stringer, Citation2020), two in the UK (Baldwin, Citation2017; N. Booth, Citation2020) and one each in Greece (Demeli, Citation2010), Australia (Fowler et al.), Portugal (R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012), South Africa (Parry, Citation2022), Mexico (Sandberg et al., Citation2021), Israel (Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008) and the Philippines (Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). Three studies included formally incarcerated participants (Baldwin, Citation2017; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008), while one study included women awaiting sentencing (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010). Thirteen studies used interviews to collect data (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; N. Booth, Citation2020; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Fowler et al.; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Parry, Citation2022; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008), one used focus groups (Stringer, Citation2020), and another used written narrative accounts (Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). Two studies used observations in addition to interviews for their data collection (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Demeli, Citation2010). Various methodologies were utilised across the included studies for study design and data analysis. Four studies used thematic analysis (Baldwin, Citation2017; N. Booth, Citation2020; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021), and three used a phenomenological approach (Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019), three used grounded theory (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Kennedy et al., Citation2020), one used content analysis (Stringer, Citation2020), one used a narrative analysis (Parry, Citation2022) and one used a strength-based exploratory approach (Fowler et al.). Two studies did not provide information regarding their methodology for analysis (Demeli, Citation2010; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007). See for further details.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies.

Four analytical themes with associated subthemes were found: ‘Barriers to Motherhood’, ‘Burden of Perceived Maternal Failure’; ‘Salvation Through Motherhood’; and ‘A Better Future’. A summary of the themes and subthemes are presented in alongside the GRADE-CERQual assessment of confidence. A detailed evidence profile for GRADE-CERQual assessment for each finding can be found in Appendix B. Additionally, a summarised audit trail of descriptive and analytical themes is included in Appendix C.

Table 4. Summary of Qualitative Findings.

Theme 1: barriers to motherhood

The first theme encompasses the subthemes of ‘Lack of institutional support for mothering’, ‘Negotiating with external caregivers’, ‘Intergenerational cycle’ and ‘Pain of separation’. The theme speaks to how these components are barriers to the women’s mothering role.

Lack of institutional support for mothering

The majority of the studies spoke to the lack of institutional support for mothering (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Fowler et al., Citation2021; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; N. Booth, Citation2020; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008). The facilities and environment within prison made it difficult for the women to fulfil their roles as mothers (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; Demeli, Citation2010; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012).

‘Arguably, the maternal experience of mothers in prison is often at best disrupted, at worst destroyed, by the location. Mary, for example, described prison as ‘an assault on her ability to be any kind of mother at all let alone a good one’ (Baldwin, Citation2017).

The practicalities of attempting to mother in prison resulted in numerous hurdles. Studies reported barriers such as the level of security, access to telephone and lack of appropriate

visiting space for children (Baldwin, Citation2017; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; N. Booth, Citation2020). Three studies reported the lack of support they perceived from prison staff and judges, and members of the broader judicial system (Baldwin, Citation2017 Fowler et al.; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007).

As Alicia stated regarding the judge who sentenced her: If you really cared about me being a good parent, what is 90 days in here really going to do for my children? … Some of us in here do have families (Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007).

From primary studies, there was a sense that participants felt staff did not value their roles as mothers and that there were institutional barriers put in place.

‘One mother felt she had limited emotional support from officers, although this was not a universal experience, and felt that simply being in prison rendered mothers ‘invisible’ and ‘unworthy’ in the eyes of the prison staff: ‘the officers didn’t care I wasn’t a mother, I wasn’t a grandmother who was feeling sad, and in pain, I wasn’t someone who had made a successful career and made one mistake I was just a prisoner, the rest … all gone’(Queenie, 64)’ (Baldwin, Citation2017).

Studies reported that women’s self-concepts as mothers were removed and their maternal identities threatened (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; Baldwin, Citation2017). Barriers such as the cost of telephone calls, writing materials, restrictions on visits as well the location of prisons made performing even a limited form of motherhood difficult (Baldwin, Citation2017; N. Booth, Citation2020; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010 Fowler et al.; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007).

I’ve got four children, and because of the money that we’re on, it’s hard not being able to speak to the kids … you’re just rushing on the phone just so you can get [time] and squeezing every phone call out of that money you’ve got on your credit. (Sarah, mother of four) (N. Booth, Citation2017).

Negotiating with the external caregiver

The complexity of negotiating children’s external care also acted as a barrier to the women’s mothering abilities (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; N. Booth, Citation2020; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Fowler et al.; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020). Women were in a precarious position as they often had ambivalent feelings toward the caregiver, being both grateful that their children were looked after and having a desire for their children to be parented differently (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Stringer, Citation2020).

Sabrina felt a conflict: she was grateful for her mother’s willingness to care for her children but concerned about her mother’s parenting style (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016).

Other women were more explicit in stating that they were better mothers than the external caregivers and expressed frustration with how their children were being cared for (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Stringer, Citation2020).

My niece is very strict with my daughter; I understand she has to be like that sometimes, but not excessively like one time when she hit my daughter. And I had an argument with her “I won’t allow you or anyone else to hit my daughter” (R. Granja et al., Citation2015).

Studies reported how women were often denied contact with their children. This may have been a form of ‘punishment’ from the external caregiver (Demeli, Citation2010; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012); or due to personal or practical issues with the caregiver, such as ‘procrastination’ or difficulties travelling (Stringer, Citation2020).

‘I didn’t expect them to say to me, “well done”. But they are taking revenge on me through the kids’ (Demeli, Citation2010).

While there was a variety of experiences it was clear that due to a lack of control and the fact these external caregivers were the gatekeepers to their children the women’s relationship with the external caregiver heavily influenced their ability to enact a maternal role. The women’s ability to maintain a relationship with their children was not possible without the constant support of the caregiver. As such their ability to perform their mothering role was highly vulnerable.

Intergenerational cycle

The subtheme speaks to the cycle of violence, poverty and crime faced by some participants (Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Parry, Citation2022).

‘Now it’s a vicious cycle, my child is living in the same house dealing with the same issues because I’m here and can’t take care of him’ (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).

This sub-theme illustrated how women had little agency before their incarceration. The intergenerational cycle impeded their ability to mother before and during imprisonment due to the cycles’ role in their offending.

Pain of separation

The hardship and difficulties of prison are associated with the separation from their children and all that entails. Ten of the studies reported and explored the struggle these mothers felt from being separated from their children (Baldwin, Citation2017; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Fowler et al.; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). Women discussed the pain, distress and anxiety that being separated from their children brought them (Baldwin, Citation2017; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019).

‘pain to the point of numbness’ (Ursula, 48)’ (Baldwin, Citation2017).

In two of the studies, women discussed the immense pain of being separated from their babies (Baldwin, Citation2017; Fowler et al.).

I was locked in this horrible lonely, scary place with leaking breasts and no baby … I held my pillow like it was my child, and it was soaked with my milk and my tears … I felt bereft, I have never felt grief or pain like it (Beth, 19) (Baldwin, Citation2017).

Across several studies, the women spoke about the pain of not being able to help their children. The inability to comfort them when they knew they were hurting. There was a sense of guilt and pain that they were responsible for this painful separation (Baldwin, Citation2017; Demeli, Citation2010; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019).

I am angry with myself when I hear that they are sick, and I should be the one taking care of them (Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019).

Theme 2: the burden of perceived maternal failure

This theme explores the burden these women carry with them of their perceived failing of motherhood. This perceived failing drives the women to seek salvation through motherhood and leads to hope for a better future, as will be explored in the following themes. Two sub-themes contribute to this theme: ‘Guilt and shame’ and ‘Awareness of the impact on children’.

Guilt and shame

Throughout 12 of the studies, there was a sense of the guilt and shame the women felt for both the pain they had caused their children and the stigmatisation of being a ‘bad’ mother (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020). Studies reported that the stigma these women faced threatened their maternal identity and the sense of being a good mother (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012). The stigma was centred on both being a parent who had offended but was also gendered stigma (Demeli, Citation2010; Sandberg et al., Citation2021).

‘they are viewed as both ‘bad women’ and “bad mothers’ (Sandberg et al., Citation2021).

There was a sense of maternal failing, a failure to live up to society’s expectations (Baldwin, Citation2017; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020).

In several studies, women expressed feelings of guilt and self-blame for the hardships they had inflicted on their children; there was a real sense that they felt that they had let their children down (Baldwin, Citation2017; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020).

The girl failed school this year. (…) She has nothing. Her father has already been in prison. Now I am, and my sister. I won’t punish her because, in the end, it’s my fault.” Cláudia (aged 35, drug trafficking, 4 years and 8 months) (R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012).

Awareness of the impact on children

The studies have shown that these women are aware of the vast impact maternal incarceration has on children (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; N. Booth, Citation2020; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Demeli, Citation2010; Fowler et al.; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Parry, Citation2022; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020). There was an awareness among the women in several studies that their offending behaviour and resulting incarceration had a neglectful impact on their children (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015). Mothers discussed the deterioration of their relationship with their children and the distance they felt growing between them (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Demeli, Citation2010; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Stringer, Citation2020).

And then I called her, she looked at me, and it seemed like she was seeing the devil. She screamed, yelled … clung to the neck of my mother, saying she didn’t want [to be here]. She has forgotten me (R. Granja et al., Citation2015).

Mothers reported how the impact of the separation was seen in the distress of their children or challenging behaviour, that they were powerless to change (Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; N. Booth, Citation2020; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008). Other studies touched on the new roles that children were forced to take on (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Parry, Citation2022; Stringer, Citation2020). As their mothers were not at home, children took on parentified roles, helping with caregiving, being strong for their mothers and holding information that was perhaps inappropriate for their age.

In some cases, children actually exhibited some adult-like behavior and assumed the role of protective guardians of their vulnerable and dependent mothers (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010).

In some incidences, maternal incarceration was further compounded by the fact that siblings needed to be separated for caregiving reasons (Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Stringer, Citation2020).

‘Each child has a different caregiving arrangement in three different cities’ (Stringer, Citation2020)

Theme 3: salvation through motherhood

This analytical theme speaks to the salvation that the participants in the studies experienced and attempted to gain through their maternal identity and mothering roles. Motherhood was their moral identity, the innocent part of the self that had sacrificed for their children. As such, it provided them with salvation from their perceived failings. The theme comprises three sub-themes: ‘Preserving maternal identity’, ‘Children as motivation’ and ‘Protecting the child’.

Preserving maternal identity

Twelve of the studies touch on this concept of preserving maternal identity (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). The centrality and importance of maternal identity were evident throughout the studies. Women constructed moral identities from their identities as mothers (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016). Motherhood allowed them to fight the stigma and the threat to their identity. In this way, it acted as a method to absolve them of the offending and create a moral ‘good’ identity within their roles as mothers (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Demeli, Citation2010; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007). Embracing their ‘core’ identity as the ‘good’ mother allowed the women to dissociate and distance themselves from the prisoner identity (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007). Women appeared to engage in several strategies to aid the preservation of maternal identity. For example, ‘othering’; allowed participants of three studies to compare themselves to other mothers and highlighted how they were better mothers (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Stringer, Citation2020).

‘She justified why her marijuana use was different than other women’s use of harder drugs: I can’t be like, ‘oh, we’re the same type of woman’ because we’re not. If it came down to me smoking or selling my ass, I would not. I just wouldn’t smoke. That’s not an option. You’re degrading yourself as a woman, a mother, as anything’ (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016).

A fundamental way of preserving their maternal identity was to engage in any limited form of mothering, for example, doing homework over the phone with children, making parental decisions, sending money home or punishing their children (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Demeli, Citation2010; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021)

The irreplaceability of the mother is central to their survival in prison (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Demeli, Citation2010; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Stringer, Citation2020).

And the mother? They have their father, grandmother and stepmother but I mean, and the mother? Nobody replaces the mother. Nobody! (R. Granja et al., Citation2015).

Due to the centrality of maternal identity, these women desperately tried to hold onto their maternal role despite its changing nature. This preservation appeared to be adaptive as it gave them meaning in their life, providing both pride and joy (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008).

Children as motivation

Children acted as motivators in six of the studies (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Fowler et al.; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008). Women used their children as motivation to manage the distress that prison caused (Kennedy et al., Citation2020; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008).

‘What enabled me to cope was the endless thinking about my daughter. ‘The only hope was these two children’ (Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008).

Women reported that their children provided strength and some solace despite their maternal failings, as discussed in the second theme (Kennedy et al., Citation2020; R. Granja et al., Citation2015; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008).

I have three wonderful children. I hold myself close to them, I speak with them every day, and they are the ones who give me strength, affection and support. Some days I’m saddest, and I call them, and they notice I’m upset and they give me strength and courage (R. Granja et al., Citation2015).

Specifically, in three studies, the women spoke about how children acted as motivators to tackle their addiction problems and sustain personal change (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008). In two studies, women reported that providing for or protecting their children was the motivator for engaging in the offending behaviour, using their sense of motherhood as a justification for their crimes (Fowler et al.; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007).

Protecting the child

In seven of the studies, the concept of protecting or sacrificing their needs to protect their children was apparent (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Baldwin, Citation2017; N. Booth, Citation2020; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Fowler et al.; Parry, Citation2022; Stringer, Citation2020).

There was a need to protect and engage in self-sacrificing behaviour for their children to maintain their maternal identity just as ‘good mothers’ do. Participants spoke about sacrificing their need for visits to prevent children from going through the hardship of seeing their mother in prison (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019) and sacrificing luxuries to pay for telephone calls to their children (N. Booth, Citation2020).

‘The hallway, that long hallway, and then they were walking down, and they were crying. I was like, Christ, I’ll never put them through that again. And I didn’t’ (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016).

The decision of whether to tell children the truth about their mothers’ incarceration was also used to show how these women protected their children. If they chose to tell them, it was to protect them against lies, and if they decided to keep the truth from them, this was seen as protecting them against the painful truth (Fowler et al.; Parry, Citation2022). These acts of sacrifice enabled the mothers to put their children’s needs ahead of their own, thus activating their identity of the ‘good’ mother and allowing them to seek salvation through motherhood.

Theme 4: A Better Future

The final analytical theme demonstrates the hope that the participants in 11 of the studies held for the future. Across these 11 studies, participants had desires and plans for a better future for themselves and their children (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Parry, Citation2022; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). The theme encompasses two subthemes; ‘Benefits of incarceration’ for the women and ‘Hopes for the future’.

Benefits of incarceration for the women

Ten of the studies reflect on the benefits of imprisonment for the women (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Parry, Citation2022; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). In four of the studies, participants talked about how prison gave them both the time and the tools to become better mothers (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012).

Being in here, I know now I can be happy and survive without a significant other. That’s the best thing prison did for me. Now I see myself as capable. Capable for caring for my daughters – not the best, but capable. After 25 years of unhealthy relationships, I think I am choosing them [my kids] (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).

Providing a safe refugee, incarceration allowed the women to focus on themselves, engaging in personal reflection and ‘self-improvement’ with a clarity that was not possible in their previous lives (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Parry, Citation2022).

Hopes for the future

Nine of the studies touched on the participants’ hopes for the future (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Parry, Citation2022; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Stringer, Citation2020; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). In two of the studies, participants spoke about setting an example of what not to do to their children and other troubled young people (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016; Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010).

If I find my daughter doing things that led me to being here, I will let her know, especially so she doesn’t think that I’m just scolding her or lecturing her. I’m going to let her know that I was there, and you don’t want to go there. (B. Aiello & McQueeny, Citation2016).

Participants spoke about changing both as people and as mothers. There was a strong desire in five of the studies for significant change and to be better parents (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010; Kennedy et al., Citation2020; Sandberg et al., Citation2021; Shamai & Kochal, Citation2008; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019)

‘I don’t want to do drugs, I don’t want to sell them… I just want to be a better parent to my kids’ (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).

Participants also spoke about getting a job (Celinska & Siegel, Citation2010), breaking the cycle of intergenerational violence that they were in (Kennedy et al., Citation2020) and holding out hope for a positive future (Moe & Ferraro, Citation2007; Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019).

Quality appraisal

As described within the methods section, each study’s quality was assessed using the CASP tool. There was 97% agreement between the independent reviewers for the sample of studies that were assessed. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The results of the quality appraisal of the included studies are presented in . Studies were not excluded as a result of the quality assessment as each study had the potential to add to the review. However, the methodological rigour of each contributing study contributed to the confidence assessments of each review finding, as seen in the evidence profile for each finding (Appendix B). The majority of studies failed to provide information on the impact of the researcher on the research. Several studies provided extremely little or no information regarding the design of the study or data analysis method. The results of the quality appraisal indicated that it was not always possible to assess items as detailed information regarding these questions was not included in some studies’ reports. This may be due to space limitations in publications and may represent the published report rather than the quality of the research.

Table 5. Quality appraisal results.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This systematic review synthesised the qualitative evidence of women’s mothering experience while separated from their children due to incarceration. The review provides insight into the lived experiences of incarcerated mothers. Studies were thematically synthesised, and four analytical themes with associated subthemes were identified: ‘Barriers to Motherhood’, ‘Burden of Perceived Maternal Failure’, ‘Salvation through motherhood’ and ‘A Better Future’.

The first theme captured the many barriers incarcerated mothers face to their mothering role and identity. The findings within the theme enhance our understanding of the difficulties faced by mothers when attempting to maintain their roles. In particular, the pain of the separation is evident for the women and supports research suggesting that the separation is an added stress for incarcerated mothers (Enos, Citation2001; Forsyth, 2003; Page et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the difficulties and barriers to contact with their children described in this review add to research which suggests that limited contact increases the mental health difficulties of incarcerated mothers (Houck & Loper, 2002; Powell et al., 2017). This review demonstrates the lack of perceived support from prison staff for the women’s maternal identities. This is supported by and potentially explained by research that found correctional staff hold negative and stigmatising views of incarcerated mothers (Schram, 1999). Similarly, barriers to motherhood, including institutional barriers such as difficulties with telephone calls and visits, were also found in a previous review of the impact of incarceration on parents (Page et al., Citation2021).

The review found that incarcerated women carried a burden for their perceived maternal failings. They feel tremendous guilt and shame for their crimes and incarceration. Furthermore, they were aware of this impact on their children, reinforcing their guilt and shame. While more fathers are incarcerated than mothers, maternal incarceration is argued to be more disruptive to children (Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). Children of incarcerated mothers tend to move carers and locations frequently (Caddle & Crisp, 1997). In line with the perceptions of incarcerated mothers in this review, parental incarceration is known to harm the well-being of children (Christmann et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2013; Newman et al., 2011). This sense of maternal failing may account for previous review findings that mothers have additional rates of mental health difficulties compared with other prisoners and the general population (Page et al., Citation2021). The challenges of visits and the negative impact on children have been seen to reinforce parental shame and guilt (Raikes & Lockwood, 2019).

The third analytical theme spoke to the salvation that motherhood offered to the women in the studies. Motherhood and particularly being a ‘good mother’ offered salvation from their perceived maternal failings. Preserving maternal identity was a critical tool for achieving redemption from their crimes. One of the ways that women preserved their identity was through ‘othering’ their peers (other prisoners and mothers). The practice of othering may have served to create an in-group and an out-group and, as such, increased the mothers sense of belonging and maternal competence (Stets & Lee, 2021; Tajfel et al., 1979). Women also distanced themselves from the identity of being a ‘criminal’ in order to maintain their maternal identity, as seen in a previous review (Villanueva & Gayoles, Citation2019). Additionally, previous literature and reviews have found that children act as motivators for incarcerated mothers (Enos, Citation2001; Mulligan, 2019), supporting the finding from the current review that by utilising the motivating factor of their children, women could cast themselves as ‘good’ mothers.

The final theme demonstrates the hope for the women’s future; for some, incarceration was a beneficial environment that allowed them to envisage a different future and the skills to be better mothers. Previous reviews have also found that parenting programmes or classes are beneficial to parents providing them with skills not previously taught to them (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; Page et al., Citation2021). However, one review did note that despite the benefit of parenting programmes within prison, this was rarely followed up with parenting support post-incarceration (Page et al., Citation2021). Notably, the current review appears to be the only review which discusses the benefit of prison for mothers external to the parenting programmes offered. The present review captured how the prison provided clarity and a safe space for mothers and was seen as a refuge for some of the women.

The current review provides support for much of the literature that currently exists. However, it furthers the existing literature base by providing a systematic and thorough synthesis of the qualitative literature available. The review provides a much-needed platform for the experiences and perceptions of incarcerated mothers.

Strengths and limitations of the studies included

Despite the methodological concerns discussed above, the studies reviewed for this qualitative evidence synthesis provided rich data. Strengths of the literature base lie in the large geographical spread of the studies. Despite varying judicial and custodial systems, the themes across papers were consistent. Interestingly, cultural differences which one can assume do exist were not reflected within the primary studies and as such as not discussed within the review. Notwithstanding the concerns regarding methodology, the majority of the findings were rated with high and moderate confidence. One of the review findings, ‘intergenerational impact’, had a reduced confidence rating due to a lack of adequate data contributing to it, as seen in the evidence profile in Appendix C. However, previous reviews in the area supported this finding of an intergenerational impact (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; Page et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review analysed and synthesised the experiences of 479 incarcerated mothers. Throughout the studies, similar themes and findings were included. The use of a thematic synthesis methodology allowed for the review to go beyond simply summarising the existing data and provided a synthesis. However, as with any review, there were several limitations. Despite having a robust and tested search strategy, several key papers were not found until forwards and backwards searching. These studies were not captured in the initial database searches due to the difficulty of searching for qualitative studies due to inadequate indexing and the use of quotations as titles. Although difficult to search for qualitative findings, the reviewer carried out a systematic search, strictly adhering to inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The lack of a complete independent second review for the first screening stage could also be considered a limitation. However, the limitation was minimised as the second reviewer screened 20% of papers at the initial screening stage. Notably, there were few discrepancies at that point. The screening process was strengthened by a complete independent review at the second screening stage. As discussed in the methods section, grey literature was not included in this review primarily due to the scope and time restraints of the review. However, this may have weakened the review as there are a number of unpublished theses in the area.

Similarly, the second reviewer independently reviewed a percentage of the quality appraisals and data extraction. This was considered a limitation of the review however; few discrepancies were found. To mitigate the limitations, the first reviewer systematically screened, appraised, and extracted the data and was in constant discussion with other research team members.

Implications for future research and practice

Implications for research and practice have been developed based on the overview of studies included in this review and the GRADE-CERQual assessments of the review findings. As discussed, improved reporting is needed in qualitative studies, particularly around research design, researcher reflexivity, and data analysis procedures. The often-small word count of journals may hinder detailed reporting as qualitative researchers may prioritise rich results sections rather than providing methodological information. However, there is a need for greater transparency with reporting research methods, particularly reflections on how the researchers may influence their research and the interpretation of results. Furthermore, comprehensive indexing and labelling of qualitative studies are required to improve the ability for relevant studies to be captured within systematic searches and reduce the need for hand searching.

In light of the findings, greater support for incarcerated mothers and their mothering roles is needed across custody settings. In particular, the barriers to contact include the cost of telephone calls, the unsuitable visiting environment and the distance between the prison and the children’s location. One of the studies included in this review called for in-cell phones to further facilitate accessible contact (N. Booth, Citation2020). Internationally there are varying levels of contact between mothers and their children. In a number of regions such as Scandinavia and France, overnight visiting with families is permitted. In recent years, there has been a move toward this in the UK (Cooper-Sadlo et al., Citation2019). Previous research has found that enhanced family contact benefits the children of incarcerated parents (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011). The current review suggests that it may be useful to improve maternal distress. Furthermore, development and training of the prison workforce to highlight the benefits of supporting contact and mothering may be beneficial. This could potentially reduce unconscious bias in staff and lead to less pejorative views of incarcerated mother’s.

Preserving the maternal identity was vital for the women included in this review. Parenting programmes have been found to activate the maternal role and increase mothering motivation (Kennon et al., 2009). Parenting programmes are thought to improve bond and communication with children and are hoped to benefit the well-being of both the child and parent (B. L. Aiello, Citation2011; R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012). Given that incarcerated mothers tend to be the primary caregiver prior to incarceration, parenting programmes and contact support may be particularly important when considering mother and child reunification post-incarceration. Furthermore, there are tentative links between parenting programmes and reduced recidivism (R. P. G. Granja et al., Citation2012). As such, when developing programmes for incarcerated mothers, the importance of the maternal identity and promoting the maternal role should be considered.

Women may require additional mental health support following the separation from their child(ren) (Crewe, Citation2020). Therapeutic staff, including psychologists working within prison settings, should be aware of the multifaceted impact of being an incarcerated mother. Space during therapeutic sessions should be given to the conflictual feelings of their motherhood as a source of shame and stigma as well as a source of redemption. Therapeutic space should also be provided for the ambivalent feelings of their relationship with the children’s caregivers.

Conclusion

This systematic review synthesised data from 15 qualitative studies and addressed the need for a comprehensive systematic synthesis of the qualitative evidence of the lived experience of incarcerated mothers. The lived experiences of 479 incarcerated women were collated and analysed. The review’s findings emphasised the importance of the maternal role and identity for incarcerated mothers. Furthermore, it highlighted the barriers they faced to fulfilling those roles. While it is expected that the mothering role will be disrupted due to the nature of incarceration greater institutional support could be utilised to improve the ability of incarcerated women to engage in mothering. While the mothering role is the source of much shame and stigma as women are cast as ‘bad’ mothers, it also serves to offer them redemption and cast themselves in a new positive light. Their maternal identities provide the opportunity for hope and motivation for a better future. The findings from the current review suggest that women should be facilitated to engage with and fulfil their maternal role as much as possible while incarcerated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aiello, B. L. (2011). Mothering in jail: Pleasure, pain, and punishment. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 72(5–A), 1782.

- Aiello, B., & McQueeny, K. (2016). How can you live without your kids?”: Distancing from and embracing the stigma of“incarcerated mother. Journal of Prison Education and Reentry, 3(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.15845/jper.v3i1.982

- Baldwin, L. (2017). Motherhood disrupted: Reflections of post-prison mothers. Emotion, Space and Society, 26, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2017.02.002

- Booth, N. (2017). Prison and the family: An exploration of maternal imprisonment from a family-centred perspective. University of Bath UK].

- Booth, N. (2020). Disconnected: Exploring provisions for mother–child telephone contact in female prisons serving England and Wales. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 20(2), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895818801806

- Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Gerhardus, A., Wahlster, P., van der Wilt, G. J., Mozygemba, K., Refolo, P., Sacchini, D., & Tummers, M. (2018). Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 99, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.003

- Celinska, K., & Siegel, J. A. (2010). Mothers in trouble: Coping with actual or pending separation from children due to incarceration. The Prison Journal, 90(4), 447–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885510382218

- Cooper-Sadlo, S., Mancini, M. A., Meyer, D. D., & Chou, J. L. (2019). Mothers talk back: Exploring the experiences of formerly incarcerated mothers. Contemporary Family Therapy, 41(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-018-9473-y

- Crewe, H. (2020). ‘No babies in prison?’-Norway’s Exception Explained. Crewe, H.(2020)“no Babies in Prison.

- Crewe, H. (2020) “No Babies in Prison?” - Norway’s Exception Explained Cambridge Open Engage . https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/5f94c2a58f3ba900111bdc84

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP (Qualtative Studies Checklist).

- Demeli, P. T. (2010). Mothers under confinement: Maternal reflections in a Greek prison for women. Journal of Mediterranean Studies, 18(2), 341–360.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Sutton, A., Shaw, R., Miller, T., Smith, J., Young, B., Bonas, S., Booth, A., & Jones, D. (2007). Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907779497486

- Enos, S. (2001). Mothering from the inside: Parenting in a women’s prison. Suny Press.

- Fowler, C., Rossiter, C., Power, T., Dawson, A., Jackson, D., & Roche, M. A. (2021). Maternal incarceration: Impact on parent–child relationships. Journal of Child Health Care, 26(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935211000882

- Glenton, C., Bohren, M., Downe, S., Paulsen, E., & Lewin, S. (2020). “Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Qualitative Evidence Syntheses, Differences From Reviews of Intervention Effectiveness and Implications for Guidance.“ International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21 (2022), doi:16094069211061950 .

- Granja, R. P. G., Cunha, M. I. P. D., & Machado, H. (2012). Children on the outside: The experience of mothering among female inmates 3rd Global Conference Experiencing Prison. 2012, 9–11. Maio, Praga, República Checa.

- Granja, R., da Cunha, M. I. P., & Machado, H. (2015). Mothering from prison and ideologies of intensive parenting: Enacting vulnerable resistance. Journal of Family Issues, 36(9), 1212–1232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14533541

- Kennedy, S., Mennicke, A., & Allen, C. (2020). ‘I took care of my kids’: Mothering while incarcerated. Health & Justice, 8, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-020-00109-3

- Lewin, S., Booth, A., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Rashidian, A., Wainwright, M., Bohren, M. A., Tunçalp, Ö., Colvin, C. J., Garside, R., Carlsen, B., Langlois, E. V., & Noyes, J. (2018). Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. 13(S1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3

- Moe, A. M., & Ferraro, K. J. (2007). Criminalized mothers: The value and devaluation of parenthood from behind bars. Women & Therapy, 29(3), 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v29n03_08

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Parry, B. R. (2022). The Motherhood Penalty-Understanding the Gendered Role of Motherhood in the Life Histories of Incarcerated South African Women. Feminist Criminology, 17 (2), 274–292.

- Sandberg, S., Agoff, C., & Fondevila, G. (2021). Doing marginalized motherhood: Identities and practices among incarcerated women in Mexico. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 10(1), 15–29.

- Shamai, M., & Kochal, R. -B. (2008). “Motherhood starts in prison”: The experience of motherhood among women in prison. Family Process, 47(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00256.x

- Stringer, E. C. (2020). Managing motherhood: How Incarcerated mothers negotiate maternal role-identities with their children’s caregivers. Women & Criminal Justice, 30(5), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2020.1750538

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Villanueva, S. M. P., & Gayoles, L. A. M. (2019). Lived experiences of incarcerated mothers. Philippine Social Science Journal, 2(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.52006/main.v2i1.55